Dynamics of gut microbiota development in healthy term infants during the first month of life

Priputnevich T.V., Denisov P.A., Muravieva V.V., Lyubasovskaya L.A., Isaeva E.L., Shabanova N.E., Bembeeva B.O., Trofimov D.Yu., Balashova E.N., Zubkov V.V., Nikolaeva A.V.

The establishment of the gut microbiota is a crucial developmental stage for infants in the first month of life. The sequential colonization of the gut and initiation of immunological signaling cascades through intestinal receptors represent an evolutionarily determined strategy for postnatal adaptation. Disruptions to this sequence, such as cesarean delivery, formula feeding, or preterm birth, may lead to adaptive disturbances ranging from mild digestive disorders to life-threatening conditions such as necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and sepsis. Therefore, comparing the gut microbiota of newborns at different time points is essential for identifying the pathological trends that may precede NEC.

Objective: To assess changes in the composition of the gut microbiota in healthy term infants during the first month of life.

Materials and methods: Gut microbiota samples were collected from term newborns delivered at the V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Samples were obtained at three time points: day 1 of life (meconium), day 7, and day 30 of life. The microbiota composition was analyzed using 16S rRNA gene metagenomic sequencing.

Results: The study revealed significant differences in microbiota composition between the first week of life and day 30, a period critical for NEC development. During the first week, Staphylococcus species predominated, and their relative abundance declined on days 7 and 30. Concurrently, Escherichia coli colonization progressively increased, peaking on day 30, indicating the gradual establishment of this species in the infant gut. The relative abundance of Bifidobacterium species varied significantly across the time points. By the end of the first month, an increase in Bifidobacterium animalis was observed, indicating the onset of probiotic microbiota formation. These findings emphasize the critical role of the early postnatal period in shaping the gut microbiota and its potential impact on the immunological and physiological development of the newborn.

Conclusion: The first days of life are critical for establishing the gut microbiota, characterized by an active transition from facultative anaerobes to obligate anaerobic microorganisms. Timely colonization by Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria plays an important preventive role against NEC. The observed increase in microbial diversity with postnatal age reflects the gradual formation of a stable gut microbiome.

Authors' contributions: Priputnevich T.V., Zubkov V.V., Nikolaeva A.V. – study supervision; Denisov P.A. – bioinformatic and statistical analysis, visualization, drafting of the manuscript, interpretation; Isaeva E.L., Muravieva V.V., Bembeeva B.O. – preparation of microbiological material, drafting of the manuscript; Shabanova N.E., Lyubasovskaya L.A. – drafting of the manuscript, final approval of the version for submission; Balashova E.N., Zubkov V.V. – data collection; Trofimov D.Yu. – molecular genetic studies, drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The study was carried out as part of the Ministry of Health of Russia's state task, “Development of an integrated approach to diagnosing and correcting dysbiotic disorders of the intestinal microbiota caused by antibacterial therapy in newborns” (124020600025-2).

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P (Ref. No. 03 of March 21, 2024).

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Priputnevich T.V., Denisov P.A., Muravieva V.V., Lyubasovskaya L.A., Isaeva E.L., Shabanova N.E., Bembeeva B.O., Trofimov D.Yu., Balashova E.N., Zubkov V.V., Nikolaeva A.V. Dynamics of gut microbiota development in healthy term infants during the first month of life.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2026; (1): 45-54 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.371

Keywords

Human evolution and the development of metabolic and signaling systems are inextricably linked to the evolution of the microbiome, both at the species level of Homo sapiens and within individual organisms. Consequently, the human microbiota has become a central focus of research in fundamental sciences and applied fields, particularly in clinical medicine. This research is particularly relevant because the microbiome substantially influences immunity, metabolism, and the development of various diseases. Furthermore, modern technologies, such as whole-genome sequencing, enable increasingly detailed exploration of its structure and function, opening new avenues for diagnosis and therapy.

Obstetrics and neonatology offer unique opportunities to study the human microbiota, allowing the investigation of both vertical (mother to child) and horizontal (environmental) colonization of various biotopes from birth. This is essential for determining the role of specific microbial species in establishing normocenosis and the development of pathological conditions, as well as for identifying the predictive characteristics of microbiota states and their protective properties.

Despite extensive research, the existence of an intrauterine microbiota remains a topic of debate. While some studies have demonstrated the presence of bacterial DNA in the fetus, placenta [1, 2], and uterine cavity [3, 4], conclusive evidence supporting a stable intrauterine microbiota characteristic of all human fetuses remains lacking.

The formation of a stable microbiome on the mucous membranes and skin begins during passage through the maternal birth canal. Colonization of the vaginal and perianal regions initiates a series of immunological and biochemical reactions mediated by Toll-like receptors in the neonatal intestine. The response to colonization depends not only on the presence of microorganisms on the skin or mucosa but also on the maturity of the receptor apparatus, its ability to recognize microorganisms and initiate signaling pathways, and the formation of stable biofilms.

Enterocytes in healthy term infants are known to be immature immediately after birth. Their maturation is triggered by the activation of toll-like receptor type 2, whose ligands include structural components of gram-positive bacteria and bacteroids [5, 6]. Conversely, activation of toll-like receptor type 4, whose expression is increased in embryos and preterm animals and humans, and whose ligands are lipopolysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria, leads to the initiation of an inflammatory cascade and the development of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) [6–8]. Numerous studies have confirmed the beneficial effects of probiotic therapy in NEC; however, the extent to which such therapy can prevent this life-threatening disease, particularly in extremely preterm infants, is unclear. Furthermore, it is unknown which bacteria can adhere to and persistently colonize the intestine from early life in preterm infants and which can do so only until a certain stage of receptor apparatus maturation, subsequently passing through the intestine transiently without establishing stable colonization.

Previous studies have shown that lactobacilli can colonize the intestine at high titers from birth [9], indicating that the receptor apparatus can perceive them from birth, including at an early gestational age. In contrast, bifidobacteria and obligate anaerobes, even with probiotic therapy, only become established in the intestine around the 30th day of life. The present study investigated and compared intestinal colonization in term newborns during the first month of postnatal life using 16S rRNA metagenomic sequencing. This may provide a foundation for a new stage-based approach to probiotic therapy and NEC prevention in neonates.

This study aimed to assess the changes in gut microbiota composition in healthy term infants during the first month of life.

Materials and methods

This prospective study examined the gut microbiota of healthy full-term newborns.

Ethical considerations. The study did not involve any additional invasive procedures for the newborns; biological material was collected during routine bowel movements of the newborns. The study was conducted in accordance with an approved protocol and reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Protocol No. 03, March 21, 2024). Written informed consent was obtained from the legal representatives of all the participating infants.

The fecal microbiota composition was analyzed in 20 healthy full-term newborns delivered at the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P at three time points: day 1 (meconium), day 7, and day 30 (20 samples per time point). Stool and meconium samples were collected in sterile disposable containers and transported to the laboratory for analysis. The investigation employed 16S rRNA gene-based metagenomic sequencing.

Metagenomic analysis

For metagenomic assessment, native fecal samples were diluted tenfold in physiological saline and transported to the laboratory in sterile Eppendorf tubes for further analysis. Prior to analysis, the samples were pre-cleaned to remove external contaminants and non-target materials, thereby improving the analytical accuracy.

High-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms employing a targeted approach were used for metagenomic profiling. The hypervariable V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was selected for amplification to improve the taxonomic resolution at the family and genus levels of the bacterial microbiota. 16S DNA libraries were prepared according to the Illumina "16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation" protocol. Libraries were configured to generate paired-end reads of at least 250 nucleotides (2×250 bp), ensuring adequate sequencing depth and read accuracy.

Before sequencing, the library quality was verified using electrophoresis and quantitative fluorescence-based assays to exclude short or degraded fragments. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina platform, following the manufacturer's recommendations. Each microbiota sample yielded at least 5,000 paired-end reads, ensuring statistical reliability and representativeness of the data.

Metagenomic sequencing data processing

Following sequencing, raw sequencing data were initially assessed using FastQC [10] to control read quality and identify potential issues with adapters, low-quality bases, and quality distribution across read lengths. The quality control results informed decisions regarding the need for further cleaning. Subsequent data processing was performed using Trimmomatic [11], which removed adapter sequences, low-quality bases from read ends, and short reads, thereby improving the data quality for subsequent analysis.

The cleaned sequences were taxonomically classified using Kraken2 [12], which efficiently matches reads to a reference database to rapidly determine microbial taxa. To simplify the processing and visualization of the classification results, the KrakenTools package [13] was used to generate detailed reports and graphs displaying taxonomic distributions. Bracken [14] was used for a more accurate quantitative analysis of the relative abundance of taxa. Bracken redistributes reads based on genome length and applies other corrections to improve the estimates of microbial proportions in samples.

Statistical analysis

For statistical processing and biodiversity analysis, Rstudio (2025.05.1, build 513) and R libraries, such as vegan [15] and phyloseq [16], were used.

The vegan package was used to calculate α- and β-diversity metrics, conduct multivariate analyses (e.g., NMDS, PCoA), and evaluate between-group differences via PERMANOVA. The phyloseq package supported the structured management of taxonomic and metadata information and enabled comprehensive visualization of the microbial community structure and variability.

Rare taxa were filtered, and the data were normalized to reduce technical artifacts and differences in sequencing depth, ensuring a more accurate interpretation of the results. Analyses were performed on a virtual machine running Ubuntu 24.04.2 LTS operating system. Graphs and figures requiring advanced formatting and high-resolution rendering were created using OriginLab 2021 (OriginLab Corporation, USA).

The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD), or median with interquartile range (Q1; Q3). For dependent samples, a repeated-measures one-way ANOVA (ANOVA RM) was applied. Where statistically significant differences were identified, pairwise comparisons were conducted using Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction. To assess β-diversity among microbial communities, paired PERMANOVA tests were performed using Bray–Curtis distance matrices.

Results

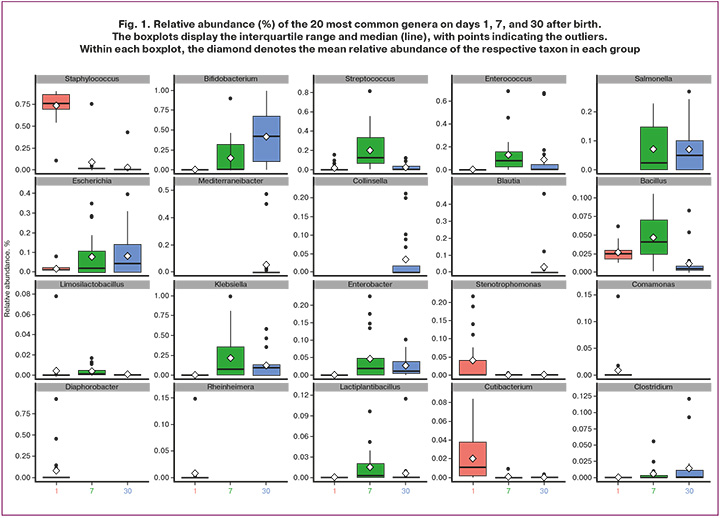

In the initial stage, the relative abundance of the detected microbial species was analyzed. In metagenomic analysis, abundance (relative abundance) denotes the proportion of a given microorganism (or taxon) within the overall sample, reflecting its quantitative contribution to the microbial community. This parameter is a key descriptor of microbiota structure and composition, indicating which species are dominant and which are rare, based on the number of DNA sequence reads.

Particular attention was paid to the 20 most prevalent species (Fig. 1). At the first time point, the microbiota was predominantly represented by species of the genus Staphylococcus, including Staphylococcus aureus. Their abundance decreased by day 7 of life. The highest values were observed on day 1 (1 d: 0.69 (0.16); 7 d: 0.08 (0.2); 30 d: 0.03 (0.09); ANOVA RM test, p<0.001). With Bonferroni correction, the p values for S. aureus indicated statistically significant differences between days 1 and 7 (t-test, p<0.001) and between days 1 and 30 (t-test, p<0.001), with no differences between days 7 and 30.

The relative abundance of Escherichia coli was low on day 1, followed by a statistically significant increase across time points, with peak values on day 30 (1 d: 0.019 (0.017); 7 d: 0.08 (0.11); 30 d: 0.089 (0.11); ANOVA RM test, p=0.038). After Bonferroni correction, significant differences were identified only between days 1 and 30 (t-test, p=0.014).

The abundance of Bifidobacterium species also differed significantly across time points. For Bifidobacterium longum, the most pronounced increase was observed on day 30 (1 d: 0.00 (0.00); 7 d: 0.067 (0.095); 30 d: 0.18 (0.14); ANOVA RM test, p=0.011). After Bonferroni correction, the upward trend persisted but did not reach statistical significance (t-test, 7 vs. 30 d, p=0.019). Bifidobacterium animalis reached its highest abundance by day 30, although the differences were not statistically significant (1 d: 0.00 (0.00); 7 d: 0.074 (0.098); 30 d: 0.145 (0.137); ANOVA RM test, p=0.077; t-test, 7 d vs. 30 d, p=0.12). The relative abundance of Bifidobacterium breve remained low throughout the observation period, without statistically significant variation (1 d: 0.00 (0.00); 7 d: 0.0024 (0.0036); 30 d: 0.057 (0.099); ANOVA RM test, p=0.2).

The abundance of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum showed a moderate increase by day 7 (1 d: 0.00 (0.00); 7 d: 0.014 (0.019)), but this difference was not statistically significant after Bonferroni correction (t-test, p=0.024). Levels subsequently declined by day 30 (0.006 (0.011)), remaining slightly above baseline, as confirmed by the ANOVA RM test (p=0.13), indicating the relative stability of this species in the early neonatal period.

Although the abundance of Limosilactobacillus fermentum was low (1 d: 0.039 (0.075); 7 d: 0.033 (0.038); 30 d: 0.00 (0.00)), a statistically significant increase was observed on day 7 (ANOVA RM test, p=0.46; t-test, p=0.008).

Streptococcus pneumoniae exhibited marked variability in colonization (1 d: 0.009 (0.015); 7 d: 0.11 (0.09); 30 d: 0.012 (0.016); ANOVA RM test, p<0.001), with a distinct peak on day 7, whereas the levels on days 1 and 30 were substantially lower (1 d vs. 7 d: t test, p=0.0007; 7 d vs. 30 d: t test, p=0.0009). The plausibility of such a high prevalence of S. pneumoniae in the neonatal gut is questionable and likely reflects the limitations of metagenomic sequencing in discriminating closely related streptococcal taxa. This interpretation is supported by culture-based studies of the intestinal microbiota, which have demonstrated colonization by Streptococcus salivarius, S. oralis, S. peroris, S. parasanguinis, and S. vestibularis, all of which are phylogenetically related to S. pneumoniae. Similar temporal patterns were observed for Streptococcus thermophilus (S. salivarius subsp. thermophilus), with pronounced differences (ANOVA RM test, p<0.001): levels increased on day 7 relative to the low abundance on days 1 and 30 (1 d: 0.00 (0.00); 7 d: 0.021 (0.015); 30 d: 0.004 (0.005)). After Bonferroni correction, statistically significant differences were observed between days 1 and 7 (t-test, p=0.00015) and between days 7 and 30 (t-test, p=0.0012).

The abundance of Enterococcus faecium increased by day 7 (1 d: 0.00 (0.00); 7 d: 0.077 (0.07); 30 d: 0.018 (0.024)), followed by a decline by day 30 (ANOVA RM test, p=0.051). After Bonferroni correction, differences did not reach statistical significance (1 vs. 7 d: t-test, p>0.05; 7 vs. 30 d: t-test, p=0.042).

The abundance of Bacillus decreased towards day 30 (1 d: 0.0025 (0.0036); 7 d: 0.0035 (0.0039); 30 d: 0.001 (0.0017); ANOVA RM test, p<0.001), with a modest peak at day 7, although the difference between days 1 and 7 was not statistically significant (t-test, p>0.05). After Bonferroni correction, statistically significant differences were detected between days 1 and 30 (t-test, p=0.004) and between days 7 and 30 (t-test, p<0.001).

Overall, analysis of the neonatal microbiota in early life revealed considerable changes in the composition and relative abundance of major taxa during the first 30 days after birth. During the first week, species of the genus Staphylococcus, including S. aureus, predominated, with a gradual decline by day 7 and 30. Concurrently, colonization by E. coli increased, peaking on day 30, consistent with the progressive establishment of this species in the gut.

The dynamics of Bifidobacterium species are of particular interest. By the end of the first month, the abundance of B. animalis increased, indicating the onset of probiotic microbiota formation. B. longum and B. animalis reached their highest levels by day 30, underscoring their role in early microbiota development, whereas B. breve remained at low levels throughout the observation period.

Species within the genera Streptococcus and Lactobacillus exhibited substantial fluctuations during the first 7 days, with certain species (S. pneumoniae and S. thermophilus) demonstrating peak levels on day 7, potentially reflecting features of neonatal immunological adaptation. The observed decrease in Limosilactobacillus fermentum and increase in E. faecium abundance by day 30 are consistent with the ongoing dynamic restructuring of the microbiota during early life. The declining levels of Bacillus with age correspond to progressive microbial maturation and the stabilization of the gut microbiota.

These findings emphasize the importance of the early postnatal period for microbiota establishment and the potential impact of these dynamics on immunological and physiological development in newborns.

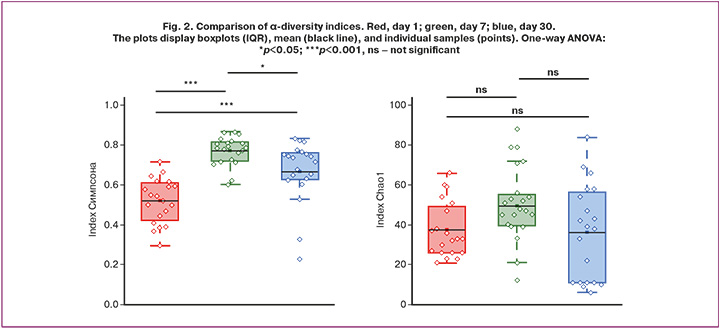

Species richness and diversity of the microbiota

To assess the species richness and diversity of the microbiota, the Simpson and Chao1 indices were used. These indices provide a comprehensive characterization of the structure and complexity of microbial communities in children of different ages and health statuses (Fig. 2).

In microbiology, the Chao1 index is widely used to estimate overall microbial diversity, particularly in sequencing-based studies, such as 16S rRNA sequencing. Because microbial surveys often detect a large number of rare taxa that occur only once or twice, simple species counts tend to underestimate the true diversity. The Chao1 index accounts for these “hidden” taxa, providing a more accurate estimate of the total number of microbial types in a sample and enabling more robust comparative analyses of microbial communities, including ecological changes and health-related shifts in microbiota composition. The Simpson index reflects biological diversity in terms of species richness and evenness within a community.

During the first month of life, the neonatal microbiome underwent substantial changes, which were reflected in the trajectories of the Chao1 and Simpson diversity indices (Fig. 2).

On the first day of life, the overall species richness was low, as indicated by the low Chao1 values. The relatively low Simpson index paradoxically indicates high diversity, reflecting the absence of a dominant species and community in the initial colonization state.

By day 7, a significant developmental shift was observed. Chao1 values reached their maximum, indicating peak species richness, whereas the Simpson index also peaked, indicating reduced diversity due to the dominance of a few rapidly proliferating species, likely Bifidobacterium spp. This period corresponds to a phase of intensive, but uneven, colonization.

By day 30, the community structure was more balanced. Although Chao1 values decreased slightly from their peak, species richness remained high, and the Simpson index returned to intermediate levels, reflecting increased evenness and complexity of the community. These changes indicate the emergence of a more mature and stable microbiome characteristic of later infancy.

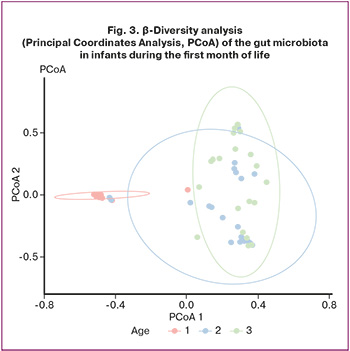

β-Diversity

β-Diversity was evaluated using a comprehensive approach that included data preprocessing, normalization, distance calculation, visualization, and subsequent statistical testing (Fig. 3). Taxonomic profiles were aggregated at the taxon level and normalized using total-sum scaling to mitigate the influence of sequencing depth and enhance the comparability across samples.

Differences in community composition were quantified using the Bray–Curtis distance, a metric that incorporates both the presence/absence and relative abundance of taxa, thus providing a robust measure of dissimilarity between samples. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA), based on classical multidimensional scaling, was used to visualize similarities and differences between communities in a two-dimensional space. Samples were color-coded by group, and 90% confidence ellipses were plotted to illustrate the degree of overlap or separation between groups.

Statistical assessment of group effects on community structure was performed using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) on the distance matrix, supplemented by pairwise PERMANOVA to identify differences between specific pairs of time points. This multistep framework yielded both visual and quantitative evidence of within- and between-group variations in microbial composition, thus contributing to the understanding of microbiota dynamics and their determinants.

Statistically significant differences were observed for the comparisons “1 vs 7” (R2=0.44, padjusted=0.003), “1 vs 30” (R2=0.46, padjusted=0.003), and “7 vs 30” (R2=0.10, padjusted=0.006). These results demonstrated pronounced temporal changes in community structure, with the largest differences between days 1 and 30, reflecting the substantial remodeling of the microbiota composition over the neonatal period.

Discussion

The PubMed database shows a steady increase in publications retrieved using the query "microbiota infants" from 1980 to the present, reaching a peak of 895 publications in 2024. Of these, 165 concerned preterm neonates ("microbiota preterm infants"). This trend underscores the importance of research focused on the establishment of the neonatal gut microbiota as a crucial event, not only for the maturation of gastrointestinal digestive function but also for the development of the infant’s immune system.

Currently, in the Russian Federation, the assessment of the human gut microbiota relies on the IS "Protocol for the Management of Patients. Intestinal Dysbiosis" [8], which standardizes 13 groups of microorganisms: bifidobacteria, lactobacilli, bacteroides, enterococci, fusobacteria, eubacteria, peptostreptococci, clostridia, various Escherichia coli variants, Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci, yeasts, and non-fermenting bacteria [8]. However, 16S rRNA sequencing data identified the dominant species of the adult human gut microbiota as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Eubacterium rectale, Collinsella aerofaciens, Clostridium clostridioforme, Bacteroides vulgatus, Anaerostipes hadrus, Ruminococcus bromii, Eubacterium hallii, Bacteroides dorei, Roseburia faecis, Dorea longicatena, and Subdoligranulum variabile [18]. This composition is not reflected in the structure of the sectoral standards. Furthermore, the regulation of the pediatric gut microbiota, encompassing the age period from birth to one year, is practically identical to that in adults. Although evidence suggests that by one year of age, a child's gut microbiota closely resembles that of the mother [19], the first year of life is characterized by the most significant transformations in both diversity and taxonomic composition of the microorganisms that will form the future microbiome.

During the first 7–14 days of life, an active shift occurs from a predominance of facultative anaerobes to obligate anaerobes belonging to three major and functionally important bacterial phyla: Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. These changes highlight the close relationship between gastrointestinal tract development and microbiota dynamics, emphasizing the need for the timely acquisition of microbial species essential for optimal immune and metabolic development. The first days of life represent a critical "window of opportunity" for gut microbiota formation, during which environmental factors, feeding mode (breastfeeding or formula feeding), and delivery mode substantially determine the future structure of the microbial community. Disruption of this process, such as in the case of cesarean sections, can lead to a more heterogeneous and less stable microbiotic environment within the first weeks, exerting long-term effects on health. Bäckhed F. et al. demonstrated that neonates born by cesarean section, lacking primary colonization by vaginal microbial species, develop a more heterogeneous microbial population compared to those born via vaginal delivery [19]. Differences in the microbiota of children born through different modes of delivery have also been reported previously [9, 20, 21].

The first month of life is particularly important because key stages of gut microbiome formation occur during this period. In the first few days after birth, a pronounced dominance of facultative anaerobes, represented by Firmicutes and Gammaproteobacteria, was observed. This finding reflects the initial stages of colonization driven by environmental exposure and mode of delivery. Early colonization by this group of microorganisms is critical for stimulating immune system development and establishing stable microbiotic communities.

Our study confirms that the first days of life represent a period of high microbiota plasticity, during which the main taxa are established. This underscores the importance of understanding these processes in developing strategies to support healthy gut development in neonates. Early intestinal colonization creates the foundation for the subsequent formation of a unique microbial ecosystem and stability of microbiome communities, influencing all aspects of a child's physiological and immunological development. Further investigation of the gut microbiota, aimed at elucidating the mechanisms of microbiota formation in neonates depending on the mode of delivery, type of feeding, and gestational maturity, is of great importance for identifying the factors that influence immune system development and overall health. In particular, the observed microbiota dynamics, from the predominance of facultative anaerobes to the dominance of obligate anaerobes, reflect complex interactions between the environment, gastrointestinal tract development, and neonatal immune system.

We observed an increase in microbial biodiversity indices in children with increasing postnatal ages.

Despite publications suggesting an etiological role for coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) in necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) [22], we believe that their presence is not a predictor of this condition. In healthy neonates, these microorganisms predominated during the first day of life without causing adverse effects and were eliminated from the gastrointestinal tract by day 7 and 30. Moreover, an association between low NEC mortality and CoNS bacteremia has been previously reported [23].

Regarding enterobacteria, our study conducted in healthy full-term infants showed that these microorganisms colonized the intestine beginning on day 7 and reached maximal levels by day 30, without increasing the risk of NEC development.

A central factor in the establishment of the neonatal gut microbiota and protection against NEC is the presence of sufficient quantities of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in the intestine, which selectively utilize human milk oligosaccharides [24]. Data on the representation of Bifidobacterium species are particularly important. By the end of the first month of life, according to our data, colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by Bifidobacterium animalis and Bifidobacterium longum increased significantly, highlighting their positive roles in early microbiota development. Therefore, probiotic therapy is the basis for NEC prevention [24], especially in preterm infants. Probiotic microorganisms block Toll-like receptor type 2 through structural components of their cell walls, creating a favorable environment for subsequent colonization by other obligate anaerobes.

Conclusion

The first few days of neonatal life represent a critical period in gut microbiota formation, characterized by an active transition from the predominance of facultative anaerobes to the dominance of obligate anaerobic microorganisms. These processes are essential for the development of the immune and digestive systems, and their disruption, such as in the case of cesarean sections, may result in a more heterogeneous and less stable microbiotic environment, potentially increasing the risk of disease in the child. Timely colonization by lactobacilli and bifidobacteria is a key factor in preventing later pathologies, such as NEC. The observed increase in microbial biodiversity with advancing postnatal age reflects the gradual establishment of a stable gut microbiome.

References

- Aagaard K., Ma J., Antony K. M., Ganu R., Petrosino J., Versalovic J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014; 6(237): 237ra65. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599

- Odendaal J., Black N., Bennett P.R., Brosens J., Quenby S., MacIntyre D.A. The endometrial microbiota and early pregnancy loss. Hum. Reprod. 2024; 39(4): 638-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead274

- Balla B., Illés A., Tobiás B., Pikó H., Beke A., Sipos M. et al. The role of the vaginal and endometrial microbiomes in infertility and their impact on pregnancy outcomes in light of recent literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024; 25(23): 13227. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijms252313227

- Moreno I., Franasiak J.M. Endometrial microbiota – new player in town. Fertil. Steril. 2017; 108(1): 32-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.034

- Ganguli K., Meng D., Rautava S., Lu L., Walker W.A., Nanthakumar N. Probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis by modulating enterocyte genes that regulate innate immune-mediated inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013; 304(2): G132-41. https://dx.doi.org/10.1152/AJPGI.00142.2012

- Gorreja F., Rush S.T.A., Kasper D.L., Meng D., Allan Walker W. The developmentally regulated fetal enterocyte gene, ZP4, mediates antiinflammation by the symbiotic bacterial surface factor polysaccharide a on Bacteroides fragilis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019; 317(4): G398-G407. https://dx.doi.org/10.1152/AJPGI.00046.2019

- Meng D., Zhu W., Shi H.N., Lu L., Wijendran V., Xu W. et al. Toll-like receptor-4 in human and mouse colonic epithelium is developmentally regulated: a possible role in necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr. Res. 2015; 77(3), 416-24. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/PR.2014.207

- ОСТ 91500.11.0004-2003. Отраслевой стандарт. Протокол ведения больных. Дисбактериоз кишечника (утв. Приказом Минздрава России от 09.06.2003 № 231). Доступно по: https://normativ.kontur.ru/document?moduleId=9&documentId=62571 [OST 91500.11.0004-2003. Industry standard. Protocol for managing patients. Intestinal dysbiosis (approved by Order No. 231 of the Russian Ministry of Health dated June 9, 2003). Available at: https://normativ.kontur.ru/document?moduleId=9&documentId=62571(in Russian)].

- Припутневич Т.В., Исаева Е.Л., Муравьева В.В., Месян М.К., Зубков В.В., Николаева А.В., Бембеева Б.О., Тимофеева Л.А., Козлова А.А., Макаров В.В., Юдин С.М. Становление микробиоты кишечника доношенных и поздних недоношенных детей, рожденных самопроизвольно и путем операции кесарева сечения. Неонатология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2023; 11(1): 42-56. [Priputnevich T.V., Isaeva E.L., Muravieva V.V., Mesyan M.K., Zubkov V.V., Nikolaeva A.V., Bembeeva B.O., Timofeeva L.A., Kozlova A.A., Makarov V.V., Yudin S.M. Development of the gut microbiota of term and late preterm newborn infants. Neonatology: news, opinions, training. 2023; 11(1): 42-56 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.33029/2308-2402-2023-11-1-42-56

- Andrews S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010. Available at: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014; 30(15): 2114-20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

- Wood D.E., Lu J., Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019; 20(1): 257. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0

- Lu J., Rincon N., Wood D.E., Breitwieser F.P., Pockrandt C., Langmead B. et al. Metagenome analysis using the Kraken software suite. Nature Protocols. 2022; 17(12): 2815-39. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41596-022-00738-y

- Lu J., Breitwieser F.P., Thielen P., Salzberg S.L. Bracken: estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2017; 3: e104. https://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.104

- Oksanen J., Simpson G.L., Blanchet F.G., Kindt R., Legendre P., Minchin P.R. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. In: CRAN: Contributed Packages. https://dx.doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan

- McMurdie P.J., Holmes S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PloS One. 2013; 8(4): e61217. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061217

- Barajas H.R., Romero M.F., Martínez-Sánchez S., Alcaraz L.D. Global genomic similarity and core genome sequence diversity of the Streptococcus genus as a toolkit to identify closely related bacterial species in complex environments. PeerJ. 2019; 6: e6233. https://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6233

- Walker A.W., Duncan S.H., Louis P., Flint H.J. Phylogeny, culturing, and metagenomics of the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2014; 22(5): 267-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2014.03.001

- Bäckhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y., Feng Q., Jia H., Kovatcheva-Datchary P. et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015; 17(5): 690-703. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004

- Korpela K. Impact of delivery mode on infant gut microbiota. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2021; 77(Suppl. 3): 11-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000518498

- Ma J., Li Z., Zhang W., Zhang C., Zhang Y., Mei H. et al. Comparison of the gut microbiota in healthy infants with different delivery modes and feeding types: a cohort study. Front. Microbiol. 2022; 13: 868227. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.868227

- Mollitt D.L., Tepas J.J., Talbert J.L. The role of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1988; 23(1): 60-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3468(88)80542-6

- Sáenz De Pipaón Marcos M., Rodríguez Delgado J., Martínez Biarge M., Pérez Rodríguez J., Sosa Rotundo G., Tovar Larrucea J.A. et al. Low mortality in necrotizing enterocolitis associated with coagulase-negative Staphylococcus infection. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2008; 24(7): 831-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00383-008-2168-y

- Patel R.M., Underwood M.A. Probiotics and necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2018; 27(1): 39-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2017.11.008

Received 15.12.2025

Accepted 24.12.2025

About the Authors

Tatiana V. Priputnevich, Dr. Med. Sci., Corresponding Members of the RAS, Director of the Institute of Microbiology, Antimicrobial Therapy and Epidemiology, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia; Professor at the Department of Microbiology named after Academician Z.V. Ermolieva, RMANPO of the Ministry of Health of Russia, t_priputnevich@oparina4.ru,https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4126-9730

Pavel A. Denisov, Researcher at the Laboratory of Bioinformatic Analysis of the Institute of Microbiology, Antimicrobial Therapy and Epidemiology, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia,

denisov@neuro.nnov.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1813-6718

Vera V. Muravieva, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology of the Institute of Microbiology, Antimicrobial Therapy and Epidemiology, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, v_muravieva@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0383-0731

Lyudmila A. Lyubasovskaya, PhD, Clinical Pharmacologist, MMCC Voronovskoye of Moscow Healthcare Department; Associate Professor at the Department of Medical Microbiology named after Academician Z.V. Ermolyeva, RMANPO, Ministry of Health of Russia, labmik@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7456-9940

Elena L. Isaeva, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Institute of Microbiology, Antimicrobial Therapy and Epidemiology, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, isaeva73@bk.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6224-8202

Natalya E. Shabanova, PhD, Associate Professor, Head of the Department of Clinical Pharmacology of the Institute of Microbiology, Antimicrobial Therapy and Epidemiology,

Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow,

117997, Russia, n_shabanova@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6838-3616

Bayr O. Bembeeva, Researcher, Institute of Microbiology, Antimicrobial Therapy and Epidemiology, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia; Teaching Assistant, Pirogov RNRMU, Ministry of Health of Russia, b_bembeeva@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8820-9903

Dmitry Yu. Trofimov, Dr. Bio. Sci., Director of the Institute of Reproductive Genetics, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, d_trofimov@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1569-8486

Ekaterina N. Balashova, PhD, Leading Researcher at the Department of Resuscitation and Intensive Care of Newborns at the Institute of Neonatology and Pediatrics, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow,

117997, Russia, e_balashova@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3741-0770

Viktor V. Zubkov, Dr. Med. Sci., Director of the Institute of Neonatology and Pediatrics, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, v_zubkov@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8366-5208

Anastasia V. Nikolaeva, PhD, Chief Physician, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health

of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, a_nikolaeva@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0012-6688

Corresponding author: Pavel A. Denisov, denisov@neuro.nnov.ru