The choice of techniques for correction of isthmic-cervical insufficience: the results of the retrospective study

Aim. Assessment of the effectiveness of different methods for correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency (ICI) and pregnancy outcomes in patients with preterm birth (PB) in history and without PB. Materials and methods. Retrospective analysis included 108 women with ICI, who underwent treatment with cervical cerclage and obstetric pessary. The patients were divided into 2 groups. Group I included 74 (66.7%) women with ICI, who had no PB in history: cervical cerclage was used in 35 (47.3%) women and obstetric pessary was used in 39 (52.7%) women. Group II included 34 (33.3%) women with ICI an PB and/or spontaneous late-term miscarriage in history: cervical cerclage was used in 24 (70.6%) patients and obstetric pessary was used in 10 (29.4%) patients. Results. The analysis results did not show significant differences between the two techniques for correction of ICI both in the group of patients with PB and with no PB in history. The assessment of gestational age for correction of ICI showed statistically significant differences in both groups: in the group of patients with PB in history, the median gestational age at cervical cerclage was 19 (17–20) weeks, and at pessary placement it was 24.5 (20–26) weeks, (p=0.015). In the group of patients with no PB in history – it was 21 (20–22) and 24 (22–26) weeks, respectively (p<0.001). Overall preterm birth rate in the group of women with no PB in history, who underwent cervical cerclage was 31.42%, and 38.46% among those who underwent obstetric pessary insertion. Term births were in 60% and 53.85% of women, respectively. Preterm birth rate in the group of patients with PB in history who underwent cervical cerclage was 45.84%, and 20% among those who underwent pessary insertion; term births were in 45.83% and 70% of women, respectively. Conclusion. In addition to prolonged support with progesterone and elimination of factors contributing to the occurrence of infection, the techniques for correction of ICI – pessary and cerclage showed similar results with regard to pregnancy prolongation, PB rates and perinatal outcomes both in the group of pregnant women with no PB and in the group of women with PB in history.Timokhina E.V., Strizhakov A.N., Pesegova S.V., Belousova V.S., Samoilova Yu.A.

Keywords

Preterm birth (PB) remains one of the common and complex problems in modern obstetrics [1–3], which accounts for about 70% of neonatal and infant morbidity and mortality rates [3–7]. Over the past decade, the rate of PB has been steadily growing at rates of 5–13% in different countries of the world [4, 5, 8, 9]. Premature infants are at high risk of complications, such as respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, intracerebral hemorrhage and cerebral palsy. Later, as premature babies are growing up, they are also at increased risk of vision and hearing loss, mental retardation, cognitive impairment and chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. [10].

PB is a polyethiologic obstetrical syndrome [4, 6], developing under the influence of a large number of genetic, biological/biophysical, psychosocial and environmental factors [4]. Risk factors for spontaneous PB is previous PB in history, cervical shortening and isthmic-cervical insufficiency (ICI) [1]. The main reason for pregnancy loss on the second trimester and PB is ICI [11], which complicates 0.1–1.0% of all pregnancies [12, 13]. At present, there is no any optimal surgical technique for correction of ICI. The most common treatment for ICI is cervical cerclage – a suture of the cervix to prevent further expansion of the cervical canal. However, for the time being, it has not been established, that cervical cerclage is the most effective technique for preventing PB in patients with ICI [12]. In addition, there are non-invasive types of treatment of ICI: medical treatment with progesterone and the use of obstetric pessaries, which can also be effective correction methods [6, 7].

The aim of this study was assessment of the effectiveness of different methods for correction of ICI and pregnancy outcomes in patients with and without PB in history.

Materials and methods

We have conducted a single-center, stratified (the patients with and with no PB in history) retrospective cohort study of the course and outcomes of pregnancy in patients, who were diagnosed with ICI and underwent cervical cerclage or obstetric pessary insertion in the Perinatal Center of S.S. Yudin City Clinical Hospital in the period from 2015 to 2020.

The diagnosis of ICI was established on the basis of anamnestic data, bimanual examination, ultrasound data on cervical shortening (cervical length less than 25 mm). Assessment of the course and outcomes of pregnancy was conducted after ICI treatment by cervical cerclage or obstetric pessary insertion (at 14–28 weeks) until delivery. The method of K.A. Otdelnova was used for sampling: 90% of research capacity, significance level at p=0.05 and minimal clinically important difference of 10% between the indicators, the number of patients involved in the study was 100 women.

In the course of the study, the following data were obtained from the histories of pregnancy and childbirth: specific features of anamnesis, the course of pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period, as well as the condition of the newborns. After collection of all data, the women who met the certain criteria were involved in the study.

Inclusion criteria were women aged 18 years and older; singleton pregnancy, cervical length ≤ 25 mm according to ultrasound cervicometry; gestational age at the time of correction 14–28 weeks (based on the date of the last menstruation and/or ultrasound examination in the first trimester); correction of ICI by the performance of cervical cerclage or obstetric pessary insertion.

Exclusion criteria; multiple pregnancy; surgery on the cervix in history (conization procedure, plastic surgery, cervical tears during previous delivery, amputation of the cervix); fetal bladder prolapse at the time of correction of ICI; acute phase or exacerbation of chronic infectious diseases.

All patients underwent correction of ICI, either by performance of cervical cerclage according to A.I. Lyubimova’s technique modified by N.M. Mamedalieva [14] using intravenous anesthesia, or by insertion of obstetric pessary, (Yunona, Types 1, 2, 3, Dr. Arabin). Before the correction procedure, the samples of vaginal smear were taken from all patients for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. When vaginal smear test results showed inflammation and/or conditionally pathogenic microflora equal to 104 CFU/kg or over, vaginal preparation with antiseptic agents and treatment with antimicrobial drugs was performed according to antibiotic susceptibility.

Cervical cerclage and obstetric pessary were removed in all patients at 37 weeks of pregnancy or with occurrence of the symptoms of PB, premature rupture of membranes and progressive infectious process.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analysis was performed using statistical software program StatTech v. 1.2.0 (LLC “StatTech”, Russia). The compliance of the quantitative indicators with the normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test (the number of women under the study was less than 50) or the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (the number of women under the study was more than 50). Quantitative indicators with the normal distribution were described using arithmetic means (M) and standard deviations (SD), and the confidence interval at the 95% confidence level (95% CI). In the absence of the normal distribution, the quantitative data we described using median (Me) and the upper and lower quartiles (Q1–Q3). Qualitative indicators that had the normal distribution and unequal variances were compared in 2 groups using Welch's t-test. Quantitative indicators with distribution different from normal distribution were compared in 2 groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical data were described by absolute values and the percentage values. Analysis of the percentage values in four-fold and multifold contingency tables was performed using Fisher's exact test (with expected values <10). The variables were statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

According to the mentioned criteria, we have performed retrospective analysis of 111 birth histories in women with ICI, who met our criteria. The patients were divided into 2 groups. group I included 74 (66.7%) women with ICI, who had no PB in history: 35 (47.3%) women underwent cervical cerclage for correction of ICI, and 39 (52.7%) women underwent obstetric pessary insertion. group II included 37 (33.3%) women with ICI and PB and/or spontaneous late-term miscarriage in history. However, 3 women in group II were excluded from final analysis due to the fact that they underwent combined correction of ICI by cervical cerclage with subsequent obstetric pessary insertion in view of progressing ICI and failed cervical stitch. Consequently, 34 women with ICI and PR in history were included in the final analysis: 24 (70.6%) patients with cervical cerclage and 10 (29.4%) women with obstetric pessary.

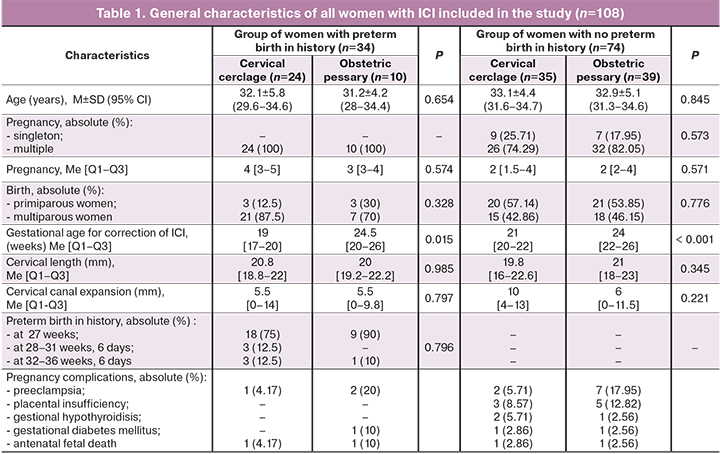

General characteristics of the patients included in the study are presented in Table I. The analysis did not show significant differences between the two methods for correction of ICI in the general characteristics, both in the group with PB and with no PB in history, including the age of pregnant women, cervical length and expansion of the cervical canal at the time of correction, the number of pregnancies and births in history.

However, the analysis of gestational age, at which the women underwent correction of ICI, showed statistically significant differences in both groups: in group with PB in history, the median gestational age for cervical cerclage performance was 19 (17–20) weeks, and 24.5 (20–26) weeks, (p=0,015), for obstetric pessary insertion; in group with no PB in history – 21 (20–22) and 24 (22–26) weeks, respectively, (p<0,001).

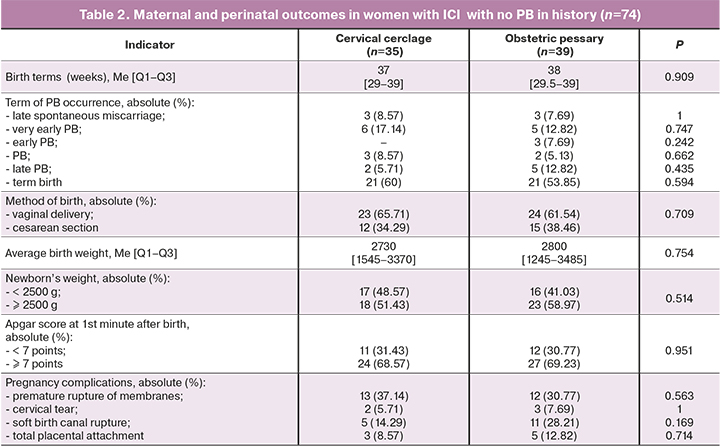

Maternal and perinatal outcomes in the group of women with ICI and with no PB in history are presented in Table 2. According to the obtained data, distribution of pregnancy termination at different gestational age in this group was as follows: late spontaneous miscarriage was in у 8.57% of women, who underwent cervical cerclage and in 7.69% of women, who underwent obstetric pessary insertion (р=1.0, RR=0.89; 95% CI: 0.17–4.72).Very early PB (at 22–27 weeks and 6 days) was in 7.14% and 12.82% of women (р=0.747; RR=0.71; 95% CI: 0.2–2.57). Early PB (at 28–30 weeks and 6 days) did not occur in the cervical cerclage group and in the obstetric pessary group. Early PB was in 7.69% of women (р=0.242). PB (at 31–33 weeks, 6 days) was in 8.57% and 5.13% of women (р=0.662; RR=0.58; 95% CI: 0.09–3.67). Late PB (at 34–36 weeks, 6 days) was in 5.71% and 12.82% of women, respectively (р=0.435; 95% CI: 0.44–13.39). Thus, the overall preterm birth rate in the cervical cerclage group was 31.42%, and 38.46% in the obstetric pessary group. Term births (after 37 weeks) had 60% and 53.85% of women, respectively (р=0.594; RR=0.78; 95% CI: 0.31–1.96). In the cervical cerclage group, the percentage of low birth weight was 48.57%, in the pessary group – 41.03% (р=0.514; 95% CI: 0.54–3.41). Apgar score at the 1st minute after birth less than 7 points was in в 31.43% and 30.77% of women, respectively (p=0.951; 95% CI: 0.38–2.76).

Maternal and perinatal outcomes in patients with ICI and PB in history are presented in Table 3.

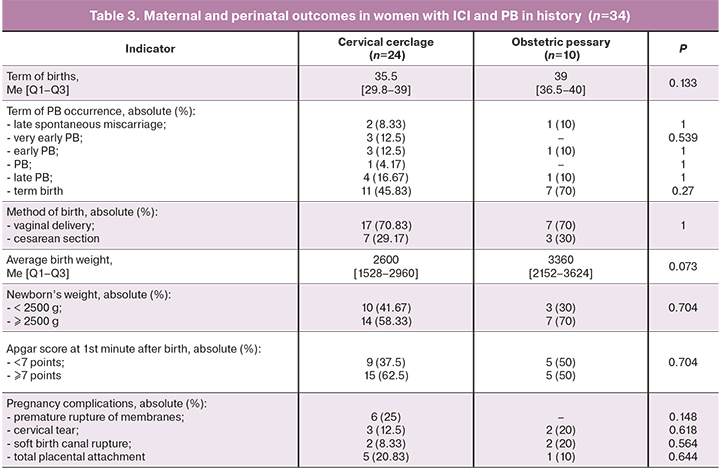

There were no significant differences in the rates and terms of PB: late spontaneous miscarriage occurred in 8.33% of women in the cervical cerclage group, and in 10% – in the obstetric pessary group (р=1.0, 95% CI: 0.1–15.23). Very early PB (at 22–27 weeks, 6 days) was in 12.5% of women in the cervical cerclage group, and there was no early PB in the obstetric pessary group (р=0.539, RR=0.78; 95% CI: 0.07–8.52). Early PB (at 28–30 weeks, 6 days) was in 12.5% and 10% of women (р=1.0). PB (at 31–33 weeks, 6 days) was in 4.17 % in the cervical cerclage group, and there was no PB in the obstetric pessary group (р=1.0). Late PB (at 34–36 weeks, 6 days) was in 16.67 and 10% of women (р=1.0, RR=0.56; 95% CI: 0.05–5.7). Thus, the overall preterm birth rate in the cervical cerclage group was 45.84%, and 20% in the obstetric pessary group.

Term births (after 37 weeks) were in 45.83% and 70% of women, respectively (р=0.27, 95% CI: 0.57–13.29). Average birth weight in the cervical cerclage group was lower compared to the obstetric pessary group — 2600 (1528–2960) g and 3360 (2152–3624) g, respectively, but the difference was not statistically significant (р=0.073). The percentage of newborns with low birth weight was 41.67% and 30%, respectively (р=0.704; 95% CI: 0.34–8.07). Apgar score at the 1st minute after birth less than 7 points was in 37.5% and 50%, (p=0.704; RR=0.6; 95% CI: 0.14–2.66).

Discussion

The study demonstrated, that in the group of patients, who underwent ICI correction with cervical cerclage and obstetric pessary insertion, there were no differences in the rates of pregnancy outcomes and the terms of PB occurrence both in the group of women with and with no PB in history.

It should be noted, that all patients under the study received a treatment with progesterone up to 34 weeks of pregnancy. In addition, all pregnant women were examined to assess the cervical and vaginal microbiome, and the women with pathogenic growth of microorganisms, received antibiotic therapy according to antibiotic susceptibility.

Statistically significant differences that were found in the analysis of the gestational age for correction of ICI in both groups can be explained by management tactics at different gestational age. So, the women with cervical length less than 25 mm undergo surgical correction with cervical cerclage at 24 weeks of pregnancy. After 24 weeks, cerclage is performed in exceptional cases, and conservative management (obstetric pessary insertion) is preferable [15].

The obtained results were confirmed by Antczak-Judycka A. et al. Their study provided evidence, that both cerclage and pessary are effective methods of pregnancy prolongation in women with ICI and risk of PB, and the choice of the correction method does not affect the method of birth, as well as neonatal outcomes [16].

According to the latest data, the use of obstetric pessary is most effective in multiple pregnancy. The study in 2020 (Jung D.-U. et al.) proved that, in cases of short cervix in twin pregnancy, the use of obstetric pessary allows to prolong pregnancy until a more favorable term and to avoid adverse perinatal outcomes [17]. In contrast, 2 meta-analysis (Saccone G. et al.) demonstrated that the use of obstetric pessary both in singleton and multiple pregnancy does not decrease the rate of spontaneous PB and does not improve perinatal outcomes [18, 19]. Kim S. et al. proved that cervical cerclage in women with PB of twins in history did now decrease the risk of PB in subsequent singleton pregnancy. Moreover, when emergency cervical cerclage was performed, the risk of PB increased, and preventive cerclage did not significantly affect the risk of PB [20].

Alfirevic Z. et al. demonstrated that all three methods for correction of ICI in women with short cervix and PB in history – cervical cerclage, obstetric pessary and treatment with progesterone are effective, however, the rate of PB in the group of women, who underwent correction with obstetric pessary was lower than in the group of women, who were treated with progesterone and underwent cervical cerclage [21]. In our study, in the group of women with ICI an PB in history, the rate of PB was also lower when obstetric pessary was used for correction compared to cervical cerclage (20% versus 45.84%), however, these data may be due to the small sample size.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that in addition to prolonged treatment with progesterone and elimination of the factors contributing to the occurrence of infection, the use of such methods as obstetric pessary and cerclage for correction of ICI result in similar terms of pregnancy prolongation, PB rates and perinatal outcomes both in the group of pregnant women with no PB and in the group of women with PB in history.

Further studies are necessary to confirm the obtained results, including the randomized trials according to the gestational age for ICI correction, and to develop a differentiated approach to management of patients with ICI.

References

- Sundtoft I., Langhoff-Roos J., Sandager P., Sommer S., Uldbjerg N. Cervical collagen is reduced in non-pregnant women with a history of cervical insufficiency and a short cervix. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017; 96(8): 984-90. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13143.

- Белоусова В.С., Стрижаков А.Н., Свитич О.А., Тимохина Е.В., Кукина П.И., Богомазова И.М., Пицхелаури Е.Г. Преждевременные роды: причины, патогенез, тактика. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 2: 82-7. [Belousova V.S., Strizhakov A.N., Svitich O.A., Timokhina E.V., Kukina P.I., Bogomazova I.M., Pitskhelauri E.G. Premature birth: causes, pathogenesis, management. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; 2: 82-7. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.2.82-87.

- Курцер М.А., Азиев О.В., Панин А.В., Егикян Н.М., Болдина Е.Б., Грабовская А.А. Лапароскопический серкляж при истмико-цервикальной недостаточности, вызванной ранее перенесенными операциями на шейке матки. Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 5: 58-62. [Kurtser M.A., Aziev O.V., Panin A.V., Egikyan N.M., Boldina E.B.,Grabovskaya A.A. Laparoscopic cerclage for isthmico-cervical insufficiency caused by previous surgery on the cervix. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017; 5: 58-62. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.5.58-62.

- Tribe R.M. A translational approach to studying preterm labour. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007; 7(Suppl. 1): S8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-7-S1-S8.

- Thain S., Yeo G.S.H., Kwek K., Chern B., Tan K.H. Spontaneous preterm birth and cervical length in a pregnant Asian population. PLoS One. 2020; 15(4): e0230125. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230125.

- Wang S.W., Ma L.L., Huang S., Liang L., Zhang J.R. Role of cervical cerclage and vaginal progesterone in the treatment of cervical incompetence with/without preterm birth history. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 2016; 129(22): 2670-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.193451.

- Romero R., Yeo L., Chaemsaithong P., Chaiworapongsa T., Hassan S.S. Progesterone to prevent spontaneous preterm birth. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014; 19(1): 15-26. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2013.10.004.

- Goldenberg R.L., Culhane J.F., Iams J.D., Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008; 371(9606): 75-84. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4.

- Park S., You Y.A., Yun H., Choi S.J., Hwang H.S., Choi S.K. et al. Cervicovaginal fluid cytokines as predictive markers of preterm birth in symptomatic women. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2020; 63(4): 455-63. https://dx.doi.org/10.5468/ogs.19131.

- Kim S., Park H.S., Kwon H., Seol H.J., Bae J.G., Ahn K.H. et al.; Korean Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology Research Group. Effect of cervical cerclage on the risk of recurrent preterm birth after a twin spontaneous preterm birth. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020; 35(11): e66. https://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e66.

- Цхай В.Б., Дудина А.Ю., Кочетова Е.А., Лобанова Т.Т., Реодько С.В., Михайлова А.В., Домрачева М.Я., Коновалов В.Н., Безрук Е.В. Сравнительный анализ эффективности хирургической и консервативной тактики у беременных с истмико-цервикальной недостаточностью при пролабировании плодного пузыря. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 6: 63-9. [Tskhay V.B., Dudina A.Yu., Kochetova E.A., Lobanova T.T., Reodko S.V., Mikhailova A.V., Domracheva M.Ya., Konovalov V.N., Bezruk E.V. Comparative analysis of surgical and conservative treatment of pregnant women with cervical incompetence in case of amniotic sac prolapse. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; 6: 63-9. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.6.63-69.

- Monsanto S.P., Daher S., Ono E., Pendeloski K.P.T., Trainá É., Mattar R., Tayade C. Cervical cerclage placement decreases local levels of proinflammatory cytokines in patients with cervical insufficiency. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017; 217(4): 455. e1-455. e8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.06.024.

- Yoo H.N., Park K.H., Jung E.Y., Kim Y.M., Kook S.Y., Jeon S.J. Non-invasive prediction of preterm birth in women with cervical insufficiency or an asymptomatic short cervix (≤25 mm) by measurement of biomarkers in the cervicovaginal fluid. PLoS One. 2017; 12(7): e0180878. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180878.

- Любимова А.И., Мамедалиева Н.М. Способ лечения истмико-цервикальной недостаточности. Патент 902733. Заявлено 19.06.1980. Опубликовано 07.02.1982. Бюллетень №5. Федеральный институт промышленной собственности, отделение ВПТБ. Описание изобретения к авторскому свидетельству. [Lyubimova A.I., Mamedalieva N.M. Method of treating istmico-cervical insufficiency, SU 902733 A1. 1982. (in Russian)].

- Леваков С.А., Боровкова Е.И., Шешукова Н.А., Боровков И.М. Ведение пациенток с истмико-цервикальной недостаточностью. Акушерство, гинекология и репродукция. 2016; 10(2): 64-9. [Levakov S.A., Borovkova E.I., Sheshukova N.A., Borovkov I.M. Management of patients with cervical insufficiency. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2016; 10(2): 64-9. (in Russian).] https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347.2016.10.2.064-069.

- Antczak-Judycka A., Sawicki W., Spiewankiewicz B., Cendrowski K., Stelmachów J. Comparison of cerclage and cerclage pessary in the treatment of pregnant women with incompetent cervix and threatened preterm delivery. Ginekol. Pol. 2003; 74(10): 1029-36.

- Jung D.U., Choi M.J., Jung S.Y., Kim S.Y. Cervical pessary for preterm twin pregnancy in women with a short cervix. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2020; 63(3):231-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2020.63.3.231.

- Saccone G., Ciardulli A., Xodo S., Dugoff L., Ludmir J., Pagani G. et al. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancies with short cervical length: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017; 36(8): 1535-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.7863/ultra.16.08054.

- Saccone G., Ciardulli A., Xodo S., Dugoff L., Ludmir J., D'Antonio F. et al. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in twin pregnancies with short cervical length: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017; 30(24): 2918-25. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1268595.

- Alfirevic Z., Owen J., Carreras Moratonas E., Sharp A.N., Szychowski J.M., Goya M. Vaginal progesterone, cerclage or cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in asymptomatic singleton pregnant women with a history of preterm birth and a sonographic short cervix. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013; 41(2): 146-51. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.12300.

Received 25.03.2021

Accepted 31.05.2021

About the Authors

Elena V. Timokhina (Corresponding author), Dr. Med. Sci., Professor of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University).Tel.: +7(499)782-30-45. E-mail: elena.timokhina@mail.ru. ORCID: 0000-0001-6628-0023. 119991, Russia, Moscow, B. Pirogovskaya str., 2-4.

Alexander N. Strizhakov, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University). Tel.: +7(499)782-30-45.

E-mail: kafedra-agp@mail.ru. 119991, Russia, Moscow, B. Pirogovskaya str., 2-4.

Svetlana V. Pesegova, Post-Graduate Student, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University). Tel.: +7(499)782-30-45. E-mail: svpesegova@gmail.com. ORCID: 0000-0002-1339-5422.

119991, Russia, Moscow, B. Pirogovskaya str., 2-4.

Vera S. Belousova, PhD, Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University). Tel.: +7(499)782-30-45. ORCID: 0000-0001-8332-7073.

119991, Russia, Moscow, B. Pirogovskaya str., 2-4.

Yulia A. Samoylova, PhD, Head of the 1st Obstetric Department of Pregnancy Pathology, S.S. Yudin Moscow Clinical Hospital. Tel.: +7(499)-782-30-18.

115446, Russia, Moscow, Kolomenskiy road, 4.

For citation: Timokhina E.V., Strizhakov A.N., Pesegova S.V., Belousova V.S., Samoilova Yu.A. The choice of techniques for correction of isthmic-cervical insufficience:

the results of the retrospective study.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 8: 86-92 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.8.86-92