Comparative characteristics of preterm births

Aim. To identify anamnestic, clinical, and morphological differences between patients who had preterm births at different gestational ages.Kurochka M.P., Volokitina E.I., Babaeva M.L., VOldokhina E.M., Markina V.V.

Material and methods. The study represents a retrospective analysis of medical records of 356 women with preterm births who were managed at the Rostov Regional Perinatal Center in 2011. The participants were divided into four groups categorized by gestational age at delivery.

Results. A history of recurrent pregnancy loss and missed miscarriage is associated with extremely preterm birth. The fundamental distinctive feature of extremely preterm birth is the presence of inflammatory changes in the umbilical cord. Cervical insufficiency is also a risk factor for early and extremely preterm birth. There were statistically significant differences in the levels of placental adaptive-compensatory reactions, specifically in detection rates of villous maturation disorders and placental circulatory disorders.

Conclusion. The duration of pregnancy depends on the condition of the placenta. With the depletion of adaptive-compensatory reactions, the risk of preterm birth increases.

Keywords

Preterm birth is a major public health problem that has not lost its relevance both in our country and worldwide. Preterm delivery is associated with neonatal morbidity and mortality and is also a leading cause of deaths among children under the age of 5 years [1, 2]. Recently, advances in neonatology have resulted in improved perinatal outcomes for preterm infants, but it has been accompanied by emerging economic problems. Neonatal care for preterm infants is associated with a significant financial burden on society. These facts highlight the need to search for new approaches to prevent premature birth. Currently, preventive measures for prematurity include the use of progestogens, tocolytics, obstetric pessaries, and cerclage [3]. But, despite all these measures, the rates of preterm birth have increased worldwide [4]. Probably, failure of prevention is associated with a lack of knowledge about the causes of preterm birth. A large number of studies have investigated the risk factors for preterm labor and premature birth. It is not known, however, why the same risk factors may be associated with both extremely preterm birth and post-term pregnancy.

In the literature on prematurity, one of the most commonly discussed risk factors is infection [5–7]. Infection of the fetal-placental unit can develop as a result of hematogenous spread or ascending infection and followed by an inflammatory response, which may trigger preterm labor. The inflammatory process in the fetal-placental unit before childbirth may be confirmed by pathomorphological analysis of the placenta [8]. Chorioamnionitis and deciduitis are the most common infectious complications. However, according to Kim Ch. J., Romero R., Chaemsaithong P., histologic chorioamnionitis is not always associated with infection; aseptic inflammation may develop in response to labor stress, which causes the body to release pro-inflammatory cytokines [9, 10]. Intervillositis, according to the literature [9], occurs due to ascending infection, while villitis is associated with hematogenous spread of pathogens. Besides, villitis impairs villous maturation. Villous maturation disorder reflects placental dysfunction, that is, inability to cope with the load that increases during a certain gestational age. The higher the degree of immaturity and the larger is the area of damage, the earlier the pregnancy will end. Thus, the infectious and inflammatory process can lead in some cases to placental insufficiency, even if the cytotrophoblast is fully implanted in the early stages [11].

According to the literature, the deciduitis, chorioamnionitis, intervillositis, and villitis, as well as peripheral blood leukocytosis, reflect the maternal body inflammatory response [12]. But there are also fetal markers of the inflammatory response. According to Kim Ch. J. et al. [9], these include funiculitis, phlebitis, and umbilical cord arteritis. Funiculitis (funnisitis) is an inflammatory process in the Wharton’s jelly involving the umbilical cord, which occurs due to the penetration of an infectious agent from the amniotic cavity, that is, in an ascending way. Omphalovasculitis occurs with hematogenous spread of the pathogen and is a marker of the systemic fetal inflammatory response [12]. The umbilical cord vein is damaged first, resulting in higher rates of phlebitis. The development of umbilical arteritis indicates more serious fetal injury and is usually associated with unfavorable neonatal outcomes. However, these assumptions continue to be the subject of much debate in the scientific world.

Cervical insufficiency also predisposes to preterm birth [13], both due to the passive opening of the cervix under pressure of the growing fetus and by infection of lower pole of membranes [14].

Another risk factor for preterm birth is intrauterine interventions [15]. This is due to endometrial injury, as well as possible injury to the cervix.

Risk factors for both spontaneous and induced preterm birth include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [16].

But exposure to risk factors not always leads to premature birth. This is due to the compensatory and adaptive capabilities of the placenta. They can be vascular and cellular (syncytial knots). Adaptive-compensatory reactions (ACR) can be moderate or mild, and sometimes completely absent.

This study aimed to identify anamnestic, clinical, laboratory, and morphological differences among patients with preterm births at different gestational ages.

Material and methods

The study represents a retrospective analysis of medical records of 356 preterm births that were managed at the Rostov Regional Perinatal Center in 2011. Pathomorphological studies were performed at the Rostov Regional Bureau of Anatomic Pathology. The study did not include preterm births with antenatal fetal death.

The cases included in the study were divided extremely preterm births (EPB) (group 1, 87/24.4%), early preterm births (group 2, 30/8.4%), preterm birth at 31–33 weeks 6 day gestation (group 3, 76/21.3 %), and late preterm birth (group 4, 163/45.8%). The distribution of patients in the groups differed from the population [17, 18] with a high proportion of EPB and a relatively small proportion of early preterm births. This can be explained by specific features of obstetric care in the Rostov region. The regional perinatal center provides obstetric care to women with complex obstetric conditions. If the severity of the condition is due to extragenital diseases, the patient is referred to another institution. According to the literature, an increase in gestational age is accompanied by increasing rates of decompensation of extragenital diseases [19]. The load on the cardiovascular system significantly increases during the gestational age of early preterm birth (28-30.6 weeks) due to an increase in the circulating blood volume, fetal growth, increasing amount of amniotic fluid, and a decrease in the contraction of the diaphragm.

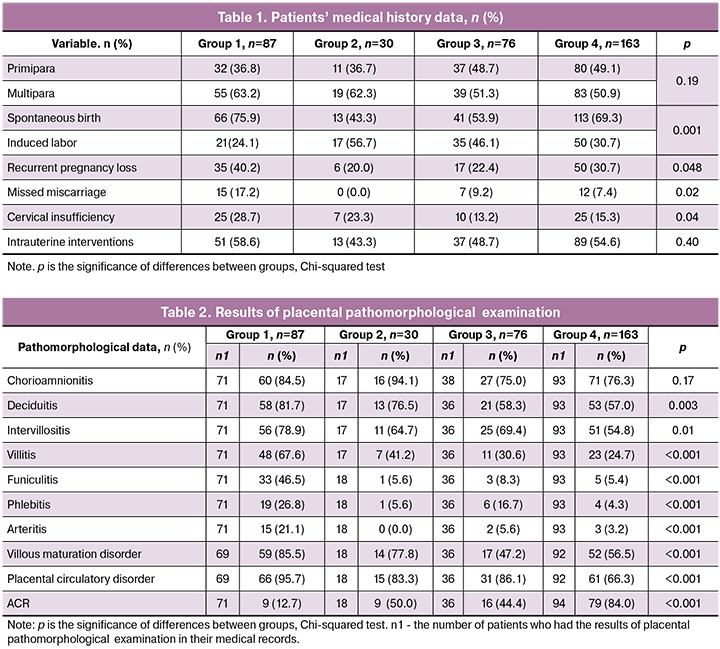

In each group, patients were divided into two subgroups - spontaneous and induced childbirth, as they differed in the leading risk factors. The largest proportion of spontaneous deliveries (66/75.9%) was in EPB group. For the above reasons, the group of early preterm birth had the largest proportion of induced births (17/56.7%). Women in groups 3 and 4 were more likely to have spontaneous births (41/53.9% and 113/69.3%, respectively) (Table 1).

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 12.0 and Microsoft Excel 2007 software. Continuous data were presented as median (Me) and quartiles Q1 and Q3 in the Me (Q1; Q3) format, as well as the minimum and maximum values. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparing numerical data between groups. Categorical variables were compared by the Chi-square test. Differences between the groups were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors for EPB.

Results and discussion

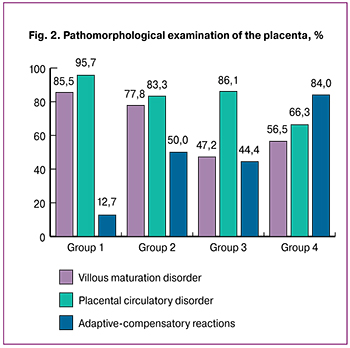

The study enrolled women aged from 17 to 45 years. Median age (IQR) in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 was 29.0 (26–32), 27 (23–32), 30 (26–36), and 28 (24–33) years, respectively. The groups did not differ in age (p = 0.15, Kruskal-Wallis test). Therefore, the majority of women with a history of preterm birth were of reproductive age (Fig. 1).

The data on the body mass index (BMI) in the study groups are shown in Fig.1. The number of patients with normal BMI in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 was 45 (51.7%),18 (60.0%), 38(50.0%), and 24.3(58.9%), respectively. Noteworthy is the difference between the groups in the rates of underweight BMI with the highest rate in women with EPB (9/10.3%); in the remaining groups, the proportion of patients with underweight BMI did not exceed 6.2%. However, no statistically significant differences between the groups were found (p = 0.41, Kruskal-Wallis test).

Most women in all four groups were multiparous, but their proportions decreased with an increase in gestational age at the time of delivery: group 1 - 55 (63.2%), group 2 - 19 (62.3%), group 3 - 39 (51.3%), and group 4 - 83 (50.9%). However, the differences between the groups were insignificant (p = 0.19) (Table 1).

Recurrent pregnancy loss was statistically significantly (p = 0.048) more common in women with a shorter gestation age. Pregnancy loss was observed in 35 (40.2%) women in EPB versus 6 (20.0%) in group 2, and in 17 (22.4%) in group 3 versus 50 (30.7%) in group 4. According to the literature [1, 20], the loss of a previous pregnancy is one of the most significant risk factors for future pregnancy loss (Table 1).

There were statistically significant differences (p = 0.02) between the study groups in proportions of women with a history of missed miscarriage. They were more likely to occur in patients with EPB (15/17.2%) and 0 (0.0%), 7 (9.2%), and 12 (7, 4%) women in groups with early preterm, preterm, and late preterm birth, respectively.

There were statistically significant differences (p = 0.037) between the study groups in proportions of women with cervical insufficiency. In the presence of cervical insufficiency, pregnancy terminated within 31 weeks in 25 (28.7%), 7 (23.3%), 10 (13.2%), and 25 (15.4%) in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively (Table 1).

It is noteworthy that more than 50% of women in groups 1 and 4 had a history of intrauterine interventions. The proportion of women with a history of intrauterine interventions was 58.6%, 43.3%, 48.7, and 54.6% in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups (p = 0.40).

As for the infectious and inflammatory risk factors, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the incidence of vaginitis, cervicitis, and bacterial vaginosis during this pregnancy. Besides, we examined the association between cervicitis and preterm rupture of the membranes and found that it was equally common, both in groups with and without cervicitis.

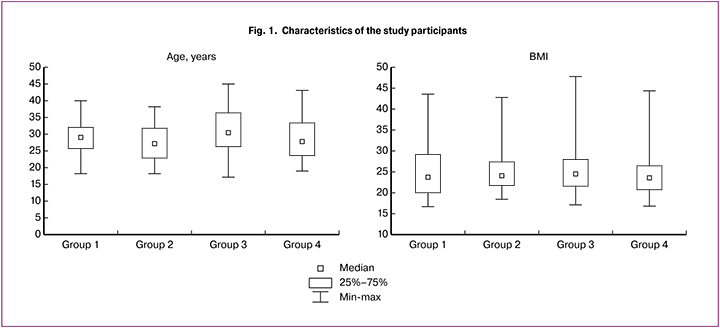

After that, we performed a statistical analysis of pathomorphological changes found in the placenta (Table 2). Medical records of some study participants had no information about pathomorphological examination of the placenta, and here we report only those that were registered (n1).

Histological chorioamnionitis mostly as serous inflammation was found approximately equally often (p = 0.17), namely in 84.5%, 94.1%, 75, 0%, and 76.3% of women in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, regardless of the gestational age at delivery. It must be emphasized that it is a question of histological chorioamnionitis, which, according to Kim Ch. J. et al. [9], is a stressful reaction to preterm birth and is not always associated with intra-amniotic infection.

Deciduitis was detected statistically significantly more often (p = 0.003) in the EPB (81.7 %) and early preterm birth (76.5%) groups. At the same time, in groups 3 and 4, inflammatory lesions in this location were less common, constituting 58.3 and 57.0%. However, the presence of deciduitis does not always indicate infection and may result from aseptic inflammation necessary to separate the placenta.

The rates of intervillositis were significantly different (p = 0.01) constituting 78.9%, 64.7%, 69.4%, and 54.8% in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Even more interesting were facts regarding the rates of villitis: 67.6%, 41.2%, 30.6%, and 24, 7% in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively (p < 0.001). The high detection rate of villitis among patients with EPB, as well as the left shift of WBC in mothers in group 1, may suggest the role of the infectious factor in the pathogenesis of extremely preterm births.

Even more interesting were facts regarding the rates of villitis: 67.6%, 41.2%, 30.6%, and 24, 7% in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively (p < 0.001). The high detection rate of villitis among patients with EPB, as well as the left shift of WBC in mothers in group 1, may suggest the role of the infectious factor in the pathogenesis of extremely preterm births.

Detection rates of funiculitis were significantly different in the study groups (p <0.001). The highest rate (46.5%) was in group 1 compared to 5.6%, 8.3%, and 5.4% in groups 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

The rate of phlebitis was 26.8%, 5.6%, 16.7%, and 4.3% in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4. The difference between groups 2 and 3 can be explained by higher rates of early induced labor. Umbilical arteritis detection rate was 21.1%, 0.0%, 5.6%, and 3.2% in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4; the difference between groups was significant (p < 0.001).

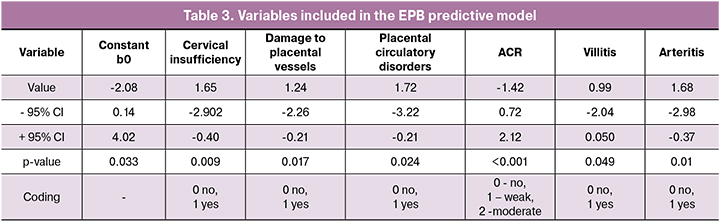

Impaired villous maturation was observed in 85.5% and 77.8% of patients in groups 1 and 2, and less frequently (47.2% and 56.5%) in patients of groups 3 and 4, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 2).

All placental morphological changes described above ultimately lead to circulatory disorders, which can trigger spontaneous preterm birth or cause induced ones. In the EPB group, the rate of histological signs of placental circulatory disorders was significantly different from other groups (p < 0.001) and was found in most (95.7%) cases, while in groups 2 and 3, that proportion was 88.2% and 86.1%. Only in women with late preterm birth, morphological signs of circulatory disorders were observed less frequently (66.3%). This can be explained by the fact that the factors leading to circulatory disturbance occur at earlier gestational ages.

If the above pathomorphological changes contribute to preterm birth, then the only characteristic of the placenta that prolongs gestation is the strength of ACR (Table 2, Fig. 2). The level of ACR was significantly different in the study groups (p < 0.001).

As shown in Fig. 2, the higher was the level of ACR, the longer was the gestational age at delivery.

We built a logistic regression model to predict the likelihood of an EPB using the existing risk factors.

Based on the above findings, we selected significant risk factors in groups 1 and 2-4 to use them as independent variables in the regression model. The dependent variable was the patient’s probability of developing spontaneous EPB depending on the values of the predictors included in the prognostic model. The model included only patients of groups 1-4 with spontaneous birth and who had documented results of the placental pathomorphological examination. Logistic regression results were considered significant at p < 0.001. A total of 142 patients met these criteria, of which 55 (38.7%) and 87 (61.3%) were women with EPB and those in groups 2–4, respectively.

The list of independent variables included in the model and their regression coefficients with the confidence intervals and their significance are given in Table 3.

A following regression equation with n independent variables was obtained:

Y=exp(b0+b1*x1+...+bn*xn)/(1+exp(b0+b1*x1+...+bn*xn)),

where b0 is the constant

b1 ....... bn - regression coefficients,

x1 ... .xn are independent variables.

In our case, b0 (constant) = -2.08

b1 (cervical insufficiency) = 1.65

b2 (damage to placental vessels) = 1.24

b3 (placental circulatory disorders) = 1.72

b4 (ACR) = -1.42

b5 (villitis) = 0.99

b6 (arteritis) = 1.68.

Logit regression Y ranges from 0 to 1 and is interpreted as the probability of the occurrence of an event (in our case, spontaneous EPB).

The sensitivity of the obtained model was 81.8% (EPB was correctly predicted in 45 out of 55 patients in group 1), the specificity of the model was 85.0% (74 out of 87 patients in groups 2-4 were defined correctly).

An example: in the presence of cervical insufficiency, placental vascular lesions, and weak ACRs in the placenta, the probability of spontaneous EPB is estimated by the model at 35.2%, the addition of villitis, and arteritis to the listed predictors increases the probability to 88.7%.

Spontaneous termination of pregnancy at 22 to 27 weeks 6 days of gestation is probably associated with the absence or weak level of ACR with concomitant pathological immaturity of the villi and placental circulatory disorders. The need for the induction of EPB arises from a combination of the infectious and inflammatory processes in the umbilical cord and the absence of ACR in the placenta.

Conclusion

The findings of our study suggest that several statistically significant differences exist between preterm births occurring at different gestational ages. Based on our results, a history of recurrent pregnancy loss, missed miscarriage, and cervical insufficiency may be considered as risk factors for extremely preterm births.

The morphological changes observed in all preterm births include impaired villous maturation, placental circulatory disorders, and low levels of ACR; these changes are more pronounced in patients with EPB.

Additional factors that influence pregnancy outcomes include inflammatory changes in the placenta (deciduitis, intervillositis, and villitis) and umbilical cord (funiculitis, phlebitis, and arteritis). Inflammatory changes identified by pathomorphological examination may also affect the formation of ACR.

References

- Семенов Ю.А., Чулков В.С., Москвичёва М.Г., Сахарова В.В. Факторы риска преждевременных родов. Сибирский медицинский журнал (Иркутск). 2015; 6: 29–33. [Semenov Yu.A., Chulkov V.S., Moskvichyova M.G., Saharova V.V. Risk factors for preterm birth. Sibirskij medicinskij zhurnal (Irkutsk)/Siberian medical journal (Irkutsk). 2015; 6: 29–33. (in Russian)]

- Lee A.C., Blencowe H., Lawn J.E. Small babies, big numbers: global estimates of preterm birth. Lancet Glob Health. 2019; 7(1): e2–e3. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30484-4

- Серов В.Н., Тютюнник В.Л., Балушкина А.А. Способы терапии угрожающих преждевременных родов. Эффективная фармакотерапия. 2013; 18: 44–49. [Serov V.N., Tyutyunnik V.L., Balushkina A.A. Methods of therapy of threatening preterm birth. EHffektivnaya farmakoterapiya/Effective pharmacotherapy. 2013;18: 44–49. (in Russian)]

- Frey H.A., Klebanoff M.A. The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016; 21(2): 68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2015.12.011.

- Айламазян Э.К., ред. Инфекционно-воспалительные заболевания в акушерстве и гинекологии: руководство для врачей. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2016. 320 с. [Ajlamazyan E.K. Infectious and inflammatory diseases in obstetrics and gynecology: guideline for physicians. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2016. 320 s. (in Russian)]

- Haahr T., Ersboll A.S., Karlsen M.A., Svare J., Sneider K., Hee L., et al. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy in order to reduce the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery – a clinical recommendation. Acta obstetricia et ginecologica scandinavica. 2016; 95: 850–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12933

- Morgan T.K. Role of the Placenta in Preterm Birth: A Review. Am J Perinatol. 2016; 33(3): 258–66. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1570379.

- Nijman T.A., van Vliet E.O., Benders M.J., Mol B.W., Franx A., Nikkels P.G. et al. Placental histology in spontaneous and indicated preterm birth: A case control study. Placenta. 2016; 48: 56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.10.00.

- Kim Ch. J., Romero R., Chaemsaithong P., Chaiyasit N., Yoon B.H., Kim Y.M. Acute chorioamnionitis and funisitis: definition, pathologic features, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 213(40): 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.040

- Kim C.J., Romero R., Chaemsaithong P., Kim J.S. Chronic inflammation of the placenta: definition, classification, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 213(4 Suppl): 53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.041

- Перепелица С.А. Этиологические и патогенетические перинатальные факторы развития внутриутробных инфекций у новорожденных (обзор). Общая реаниматология. 2018; 14(3): 54–67. [Perepelicza S.A. Etiological and pathogenic perinatal factors of development of intrauterine infections in newborns (review). Obshhaya reanimatologiya/General reanimatology. 2018; 14(3): 54–67. (in Russian)]

- Park C.W., Park J.S., Norwitz E.R., Moon K.C., Jun J.K., Yoon B.H. Timing of Histologic Progression from Chorio-Deciduitis to Chorio-Deciduo-Amnionitis in the Setting of Preterm Labor and Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes with Sterile Amniotic Fluid. PLoS One. 2015; 10(11): e0143023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143023

- Ящук А.Г., Юлбарисова Р.Р., Попова Е.М. Неразвивающаяся беременность: современные возможности консервативного ведения. Российский вестник акушера-гинеколога. 2013; 6: 29–33. [Yashchuk A.G., Yulbarisova R.R., Popova E.M. Molar pregnancy: modern possibilities of conservative management. Rossijskij vestnik akushera-ginekologa/Russian Bulletin of obstetrician-gynecologist. 2013; 6: 29–33.(in Russian)]

- Oh K.J., Romero R., Park J.Y., Lee J., Conde-Agudelo A., Hong J.S.et al. Evidence that antibiotic administration is effective in the treatment of a subset of patients with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation presenting with cervical insufficiency. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019. pii: S0002-9378(19)30495-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.017

- Батрак Н.В., Малышкина А.И. Факторы риска привычного невынашивания беременности. Вестник Ивановской медицинской академии. 2016; 21(4): 37–41. [Batrak N.V., Malyshkina A.I. Risk factors for recurrent miscarriage. Vestnik Ivanovskoj medicinskoj akademii/ Bulletin of the Ivanovo medical Academy. 2016; 21(4): 37-41.(in Russian)]

- Мансур Хасан С.Х. Особенности течения беременности и родоразрешения у женщин с гипертензивными расстройствами. Казанский медицинский журнал. 2015; 96(4): 558–563. [Mansur Hasan S.H. Features of pregnancy and delivery in women with hypertensive disorders. Kazanskij medicinskij zhurnal/Kazan medical journal. 2015; 96(4): 558–63. (in Russian)]. doi: 10.17750/KMJ2015-558

- Скрипниченко Ю.П., Баранов И.И., Токова З.З. Статистика преждевременных родов. Проблемы репродукции. 2014; 4: 11–14. [Skripnichenko Yu.P., Baranov I.I., Tokova Z.Z. Statistics of preterm birth. Problemy reprodukcii/Reproduction problems. 2014; 4: 11–14. (in Russian)]

- Преждевременные роды. Клинические рекомендации (протокол). Письмо Министерства здравоохранения РФ от 17.12.2013г. № 15–4/10/2–9480. [Premature birth. Clinical guidelines (Protocol). Letter from the Ministry of health of Russian Federation № 15–4/10/2–9480. (in Russian)]

- Лызикова Ю.А., Захаренкова Т.Н., Волкова Т.А. Экстрагенитальная патология и беременность. Учебно-методическое пособие для студентов 4, 6 курсов всех факультетов медицинских вузов, обучающихся по специальностям «Лечебное дело» и «Медико-диагностическое дело». Гомель: ГомГМУ; 2013: 64 с. [Lyzikova Y.A., Zaharenkova T.N., Volkova T.A. Extragenital pathology and pregnancy. Educational and methodical manual for students of 4, 6 courses of all faculties of medical universities. Gomel’: GomGMU; 2013: 64. (in Russian)]

- Ходжаева З.С., Федотовская О.И., Донников А.Е. Клинико-анамнестические особенности женщин с идиопатическими преждевременными родами на примере славянской популяции. Акушерство и гинекология. 2014; 3: 28–32. [Hodzhaeva Z.S., Fedotovskaya O.I., Donnikov A.E. Clinical and anamnestic features of women with idiopathic preterm birth on the example of Slavic population. Akusherstvo i ginekologiya/Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014; 3: 28–32. (in Russian)]

Received 13.03.2019

Accepted 19.04.2019

About the Authors

Marina P. Kurochka, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology Department 1, Rostov State Medical University, Rostov-on-Don, Russia. Tel.: +7(928)9054418.E-mail: marina-kurochka@yandex.ru; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5746-0727

344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakhichevanskii st., 29.

Ekaterina I. Volokitina, PhD student, Obstetrics and Gynecology Department 1, Rostov State Medical University, Rostov-on-Don, Russia. E-mail: ekavo@yandex.ru.

Tel.: +7(928)602-5002. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6892-7481

344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakhichevanskii st., 29.

Marina L. Babaeva, PhD, Assistant of Obstetrics and Gynecology Department 1, Rostov State Medical University, Rostov-on-Don, Russia. Tel. +7(918)537–5953

344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakhichevanskii st., 29.

Emma M. Voldohina, PhD, Assistant of Obstetrics and Gynecology Department 1, Rostov State Medical University, Rostov-on-Don, Russia. Tel. +79081842530

344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakhichevanskii st., 29.

Valentina V. Markina, PhD, Docent of Obstetrics and Gynecology Department 1, Rostov State Medical University, Rostov-on-Don, Russia. Тел. +7(863)2210982.

344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakhichevanskii st., 29.

For citation: Kurochka M.P., Volokitina E.I., Babaeva M.L., Voldokhina E.M., Markina V.V. Comparative characteristics of preterm births

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/ Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; 12: 76-82.(In Russian).

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.12.76-82