Management of placenta increta at delivery: our experience

Objective: To compare two surgical techniques for placenta increta management at delivery. Materials and methods: The study included 57 (100%) patients with placenta increta who delivered at the Rostov Regional Perinatal Center from 2019 to 2021. Group 1 included 32/57 (56%) patients with a placental defect <120 mm in the largest diameter and no bladder dissection difficulties, who underwent intraoperative ultrasound navigation to find the upper edge of the placenta. Subsequently, a caesarean section was performed in the lower uterine segment with an incision above the upper edge of the uterine aneurysm with application of distal hemostasis (Foley catheter), followed by metroplasty. Group 2 included 25/57 (44%) patients with a placental defect >120 mm in the largest diameter who underwent cesarean section to extract the fetus (the placenta remains in situ), suturing the uterine incision, followed by dissection of the vesical-uterine fold with excision and distal lowering of the bladder followed by distal hemostasis (Foley catheter), a second uterine incision above the herniated bulge, and metroplasty. Results: The total blood loss was 1200 (900; 1700) and 2500 (1400; 4000) ml in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.001). Blood loss > 2000 ml occurred in 4/32 (12%) and 15/25 (60%) patients in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p<0,001). Intraoperative autologous blood transfusions were performed more frequently in Group 2 (22/57 (88%)) than in Group 1 (16/57 (50%)) (p=0,004). Their volumes and the frequency and volume of blood component transfusions did not differ significantly. Conclusion: Organ-sparing surgery is an acceptable treatment option for patients with placenta increta. Surgical treatment of patients in Group 1 showed the best hemostatic effect; however, under certain conditions, a surgical technique involving two uterine incisions should be used. Authors' contributions: Bushtyrev A.V. – conception and design of the study; Bushtyrev A.V., Berezhnaya E.V. – data collection and analysis, manuscript drafting; Berezhnaya E.V. – statistical analysis; Umanskiy M.N., Khvalina T.V. – manuscript editing. Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Funding: There was no funding for this study. Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia. Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data. Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator. For citation: Umanskiy M.N., Khvalina T.V., Bushtyrev A.V., Berezhnaya E.V. Management of placenta increta at delivery: our experience. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (3): 51-56 (in Russian) https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.232Umanskiy M.N., Khvalina T.V., Bushtyrev A.V., Berezhnaya E.V.

Keywords

Reduction in maternal mortality is a priority for obstetrics and gynecology. According to the World Health Organization, massive obstetric hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for 18.6–36% of deaths. A significant contributor to mortality is abnormal placentation, including placenta accreta (20%), placenta previa (10%), and placenta increta (7%) [1–4].

A steady increase in caesarean section rates worldwide has contributed to an increase in the incidence of placenta increta. In women with a history of surgical delivery, the risk of placenta increta increases from 11% after the first operation to 60% after three or more caesarean sections [5, 6].

There are three main approaches to delivering a pregnant woman with placenta increta: single-stage or delayed organ-sparing surgery, organ-sparing surgery, and expectant management with the placenta remaining in situ [7–10]. Organ-sparing surgery for placenta increta has several advantages, including preservation of reproductive potential, reduction of intraoperative blood loss, transfusion therapy, and relatively faster rehabilitation. Despite advances in modern techniques, the proportion of hysterectomies performed for obstetric indications remains high, at 134.2/100,000 births [7, 11, 12]. The improvement of techniques for organ-sparing surgery remains an urgent issue in modern obstetrics.

The present study summarizes the experience of the surgical management strategy for the delivery of women with placenta increta in Rostov Regional Perinatal Center in 2019–2021.

This study aimed to compare the two surgical techniques for placenta increta management at delivery.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study analyzed the outcomes of 57 cases of operative delivery by caesarean section for placenta increta performed at the Rostov Regional Perinatal Center from 2019 to 2021.

In 2019–2021, 14975 pregnant women (100%) were delivered at the Rostov Regional Perinatal Center. Operative delivery was performed in 5873/14975 patients (39.2%), of whom 66/5873 (1.1%) had placenta increta as an indication for surgery. This study analyzed clinical and anamnestic data from the medical records of all pregnant women included in the study. Inclusion criteria were post-caesarean uterine scar and diagnosis of placenta increta confirmed by histological examination. The study did not include 20 pregnant women with antenatally detected uterine scar dehiscence, three pregnant women with antenatally detected placenta increta followed by histological confirmation of the diagnosis of placenta percreta, and six women with intraoperatively detected placenta increta (with histological verification of placenta increta in one patient and placenta accreta in five).

The diagnosis of placenta increta was established antenatally based on ultrasound and Doppler sonography performed to detect ultrasound signs of placenta increta and the size of the placental defect. In 12/57 cases (21%) magnetic resonance imaging was required to confirm the diagnosis.

All pregnant women who underwent an elective laparotomy in the lower midline were included in the study. All patients (57, 100%) were divided into two groups categorized by ultrasound and intraoperative findings and, correspondingly, the different operative techniques applied.

Group 1 included 32/57 (56.1%) patients with placental defects <120 mm in the largest diameter and no bladder dissection difficulties. Intraoperative ultrasound navigation was performed to identify the upper edge of the placenta. A 'window' in the uterine wall, free of placental tissue, was then found above the upper edge of the uterine aneurysm, in which an incision was subsequently made. The vesical-uterine fold was dissected, with the bladder cut off and distally lowered, followed by caesarean section in the lower uterine segment according to the findings, application of distal hemostasis, and metroplasty.

Group 2 included 25/57 (43.9%) patients with a placental defect >120 mm in the largest diameter, which required more time to thoroughly lower the bladder to visualize the lower edge of the unchanged myometrium and did not allow for supra-placental access. Group 2 patients underwent cesarean section to extract the fetus (the placenta remains in situ), suturing the uterine incision, followed by dissection of the vesical-uterine fold with excision and distal lowering of the bladder followed by distal hemostasis, a second uterine incision above the herniated bulge, and metroplasty.

Distal hemostasis, including a silicone tourniquet (Foley catheter) at the level of the lower edge of the uterine aneurysm with involvement of the uterine arteries and sacroiliac ligaments, was used as one of the main stages of surgery in the patients of both groups (57; 100%).

The effectiveness of the operative technique was assessed using the following criteria: uterine incision, ligation of the vessels supplying blood to the uterus, amount of blood loss, amount and pattern of transfusion therapy, change in hemoglobin levels before and after surgery, operation time, and length of hospital stay after delivery.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software package (version 3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The distribution of continuous variables was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data are expressed as mean and standard deviation, median and quartiles, minimum and maximum for continuous variables, and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Quantitative measures were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney test and frequencies were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Contingency tables were created, risk difference (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for binary outcomes, and statistical significance was assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

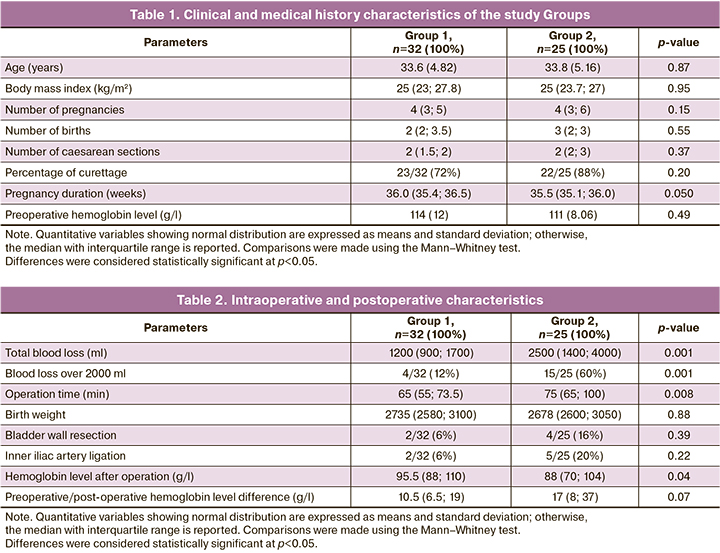

All patients with placenta increta included in the study were matched for demographic, anthropometric, somatic, and obstetric pathologies (Table 1). The mean age of the women was 33.7 (4.93) years. Preoperative hemoglobin levels were not significantly different (Group 1:114 (12) g/l; Group 2:111 (8.06) g/l) (p=0.49) (Table 1).

According to the criteria adopted in this study to assess the effectiveness of surgical intervention, the best hemostatic effect was obtained in Group 1. The total blood loss volume was higher in Group 2 (2500 (1400–4000) vs. 1200 (900–1700) ml respectively); p=0,001. At the same time, the rate of massive blood loss greater than 2000 ml was lower in Group 1 (4/32 (12%)) than in Group 2 (15/25 (60%)) (p<0.001), and RD was 47% (CI: [23%; 67%], p<0.001), which may be due to less invasive surgical intervention in Group 1 (Table 2).

Intraoperative characteristics, such as neonatal weight and Apgar scores at minutes 1 and 5, were not significantly different. The duration of the operation in the 2nd group was longer than in the 1st group (75 (65; 100) minutes and 65 (55; 73.5) minutes, respectively) due to its greater volume and stage (p=0.008) (Table 2).

In the complete blood count after surgery, hemoglobin level was lower in Group 2 (88 (70; 104) g/l) than in Group 1 (95.5 (88; 110) g/l) (p=0.04), while the difference in hemoglobin in groups 1 and 2 before and after surgery was not statistically significantly different (10.5 (6.5; 19) g/l and 17 (8; 37) g/l, respectively) (p=0.07) (Table 2).

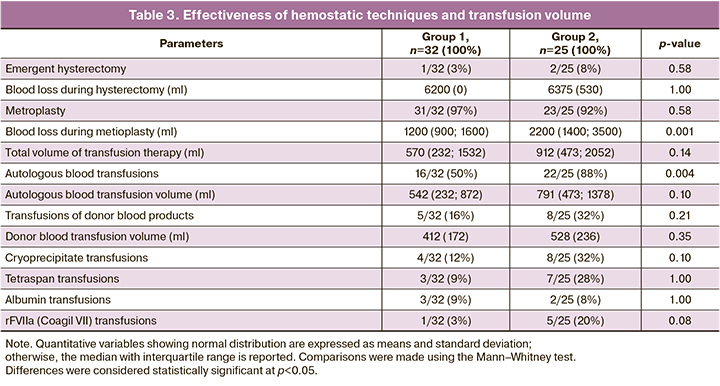

The hysterectomy rates in groups 1 and 2 were not significantly different (p=0.58):1/32 (3%) vs. 2/25 (8%) in groups 1 and 2, respectively. The indication for emergent hysterectomy in both groups was the onset of massive bleeding against the background of uterine hypotony, with a total volume of 6200 (0) vs. 6375 (530) ml in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=1.00) (Table 3). It is noteworthy that there was a decrease in blood loss in patients in both groups who underwent organ-sparing surgery. There was a decrease of blood loss during the operation: 1200 (900; 1600) vs. 2200 (1400; 3500) ml in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.001). The success of this operation was not significantly different between Group 1 (31/32 (97%)) and Group 2 (23/25 (92%)) (p=0.58) (Table 3).

Intraoperative autologous blood transfusions were performed more frequently in Group 2 (22/57 (88%)) than in Group 1 (16/57 (50%)) (p=0,004), with RD of 50% (95%CI 27%; 63%), p<0.001. Transfusion of donor blood products was required in 5/32 (16%) cases in Group 1 and 8/25 (32%) in Group 2 (p=0.21), and RD was 66% (95%CI 37%; 84%), p<0.001. The volumes of intraoperative autologous blood transfusions, transfusion of donor blood products, cryoprecipitate, tetraspan, albumin, and rFVIIa (Coagil VII) were not significantly different (Table 3).

Discussion

Finding optimal surgical treatment techniques in patients diagnosed with placenta increta is particularly relevant because of the lack of a universal protocol for organ-sparing surgery in this category of patients. The depth and area of the increta, which sometimes determined only intraoperatively, are major factors in determining the surgical strategy and outcomes for patients [13, 14]. Currently, there are no clear criteria for the choice of uterine incision site for caesarean section. According to many authors, fundal or corporal uterine incision is preferable, in which the uterine incision is made in an area not compromised by placenta increta [2, 7, 15–17]. This approach is justified, as it reliably reduces intraoperative blood loss and gives the team more time to carefully lower the bladder to visualize the lower edge of the unchanged myometrium when the fetus has been removed. However, it requires two uterine incisions, which may increase the risk of rupture in subsequent pregnancies [7, 16]. In addition, certain clinical situations (difficulty in lowering and severing the bladder, and extensive placental defects) do not allow the use of supra-placental access. Therefore, two uterine incisions are justified in such cases, as shown in the study [9]. Takeda et al. confirmed that a transverse or vertical fundal uterine incision should be made at a location sufficiently distant from the increta area when a large defect is visualized [9].

Another technique allows a single uterine incision to be made in the lower uterine segment above the upper edge of the uterine aneurysm. Many studies have reported that the line of hysterotomy is chosen according to the preoperative ultrasound scan [9, 17, 18]. However, more reliable data can be obtained by intraoperative ultrasound navigation, which allows the most accurate determination of the upper edge of the increta area, and therefore, the required location for the uterine incision [18, 19].

An invention presented in 2019 by Shmakov R.G. et al. describes the use of intraoperative sonographic navigation to determine the upper edge of the placenta and making a single transverse incision as a promising method that improves reparation after surgical intervention and reduces the amount of intraoperative blood loss [19]. The described technique used complex compression hemostasis as a method of hemostasis, involving the use of three silicone tourniquets, of which two were applied at the level of the isthmus through 'windows' formed in the broad uterine ligaments on both sides, and one at the level of the cervix [8, 19].

We present a modified technique in which one silicone tourniquet (Foley catheter) is applied at the level of the lower edge of the uterine aneurysm involving uterine arteries and sacroiliac ligaments, a similar technique is described by Altal O. [20]. A study by Vinitsky A.A. et al. demonstrated a comparative evaluation of several methods of surgical hemostasis, in which the best hemostatic effect was observed in the group with comprehensive compression hemostasis [8].

Intraoperative ultrasound navigation, placental defect size, and clinical experience determine the type of uterine incision. The operative technique described for Group 1 is associated with more effective hemostasis if a single uterine incision is possible. Surgery involving two uterine incisions allows the fetus to be removed safely in cases where the placental defect is large and there are technical difficulties in dissecting and lowering the bladder. Distal hemostasis is as effective as X-ray endovascular techniques but does not require specialist equipment or an endovascular surgeon and can be used as a temporary measure if placenta increta is detected intraoperatively and there is a need to wait for a qualified surgical team [8, 20].

Conclusion

The present analysis of the two operative techniques used in the delivery of pregnant women with placenta increta demonstrates the feasibility, safety, and appropriateness of organ-sparing surgery. It seems promising to further develop and standardize the surgical approaches and treatment methods for this group of patients.

References

- Say L., Chou D., Gemmill A., Tunçalp O., Moller A., Daniels J. et al. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2014; 2(6): 323-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X.

- Ищенко А.И., Ящук А.Г., Мурашко А.В., Чушков Ю.В., Мусин И.И., Берг Э.А. Органосохраняющие операции на матке при врастании плаценты: клинический опыт. Креативная хирургия и онкология. 2020; 10(1): 22-7. [Ishchenko A.I., Yashchuk A.G., Murashko A.V., Chushkov Yu.V., Musin I.I., Berg E.A., Birykow A.A. Organ-preserving operations on Uterus with Placenta Accreta: Clinical Experience. Creative surgery and oncology. 2020; 10(1): 22-7. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.24060/2076-3093-2020-10-1-22-27.

- Федорова Т.А., Рогачевский О.В., Стрельникова Е.В., Королев А.Ю., Виницкий А.А. Массивные акушерские кровотечения при предлежании и врастании плаценты: взгляд трансфузиолога. Неотложная медицинская помощь. Журнал им. Н.В. Склифосовского. 2018; 7(3): 253-9.[Fyodorova T.A., Rogachevsky O.V., Strelnikova A.V., Korolyov A.Y., Vinitsky A.A. Massive Hemorrhages in Pregnant Women with Placenta Previa and Accreta: a Transfusiologist’s View. Emergency Medical Care. Russian Sklifosovsky Journal. 2018; 7(3): 253-9. (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.23934/2223-9022-2018-7-3-253-259.

- Jauniaux E., Collins S., Burton G.J. Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018; 218(1): 75-87. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.067.

- Silver R.M., Barbour K.D. Placenta accreta spectrum: accreta, increta, and percreta. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2015; 42(2): 381-402.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.01.014.

- Wang Y., Zeng L., Niu Z., Chong Y., Zhang A., Mol B. et al. An observation study of the emergency intervention in placenta accreta spectrum. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019; 299(3): 1579-86. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05136-6.

- Курцер М.А., Бреслав И.Ю., Григорьян А.М., Латышкевич О.А., Кутакова Ю.Ю., Кондратьева М.А. Временная баллонная окклюзия общих подвздошных артерий при осуществлении органосохраняющих операций у пациенток с врастанием плаценты. Акушерство и гинекология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2018; 6(4): 31-7. [Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Grigorian A.M., Latyshkevich O.A., Kutakova Yu.Yu., Kondratieva M.A. Temporary balloon occlusion of common iliac arteries during organ preservation surgery in patiens with placenta ingrowth. Obstetrics and Gynecology: News. Opinions. Training. 2018; 6(4): 31-7. (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2303-9698-2018-14003.

- Виницкий А.А., Шмаков Р.Г., Чупрынин В.Д. Сравнительная оценка эффективности методов хирургического гемостаза при органосохраняющем родоразрешении у пациенток с врастанием плаценты. Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 7: 68-74. [Vinitsky A.A., Shmakov R.G., Chuprynin V.D. Comparative evaluation of the efficiency of surgical hemostatic techniques during organ-sparing delivery in patients with placenta increta. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017; (7): 68-74. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.7.68-74.

- Takeda S., Takeda J., Makino S. Cesarean section for placenta previa and placenta previa accreta spectrum. Surg. J. (N.Y.). 2020; 6(Suppl. 2): S110-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-3402036.

- Sentilhes L., Kayem G., Silver R.M. Conservative management of placenta accreta spectrum. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018; 61(4): 783-94.https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000395.

- Mei Y., Zhao H., Zhou H., Jing H., Lin Y. Comparison of infrarenal aortic balloon occlusion with internal iliac artery balloon occlusion for patients with placenta accreta. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019; 19(1): 147.https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2303-x.

- Калинкина О.Б., Нечаева М.В., Тезиков Ю.В., Липатов И.С., Аравина О.Р., Тезикова Т.А., Михеева Е.М., Коновалова Ю.И. Опыт выполнения органосохраняющих операций у пациенток с истинным врастанием плаценты в перинатальном центре ГБУЗ СО СОКБ им. В.Д. Середавина. Пермский медицинский журнал. 2020; 37(3): 84-96. [Kalinkina O.B., Nechaeva M.V., Tezikov Yu.V., Lipatov I.S., Aravina O.R., Tezikova T.A., Mikheeva E.M., Konovalova Yu.I. Experience of performing organ-preserving surgeries in patients with true ingrowth of placenta in perinatal center of Samara Regional Clinical Hospital named after V.D. Seredavin. Perm Medical Journal. 2020; 37(3): 84-96. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17816/pmj37384-96.

- Jauniaux E., Ayres-de-Campos D., Langhoff-Roos J., Fox K.A., Collins S. FIGO classification for the clinical diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019; 146(1): 20-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12761.

- Шмаков Р.Г., Пирогова М.М., Васильченко О.Н., Чупрынин В.Д., Ежова Л.С. Хирургическая тактика при врастании плаценты с различной глубиной инвазии. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 1: 78-82. [Shmakov R.G., Pirogova M.M., Vasilchenko O.N., Chuprynin V.D., Ezhova L.S. Surgery tactics for placenta increta with different depths of invasion. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (1): 78-82. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.1.78-82.

- Silver R.M., Fox K.A., Barton J.R., Abuhamad A.Z., Simhan H., Huls C.K. et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015; 212(5): 561-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.018.

- Meng J.L., Gong W.Y., Wang S., Ni X.J., Zuo C.T., Gu Y.Z. Two-tourniquet sequential blocking as a simple intervention for hemorrhage during cesarean delivery for placenta previa accreta. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2017; 138(3):361-2. https://dx.doi.org/10/1002/ijgo.12199.

- Hussein A.M., Elbarmelgy R.A., Elbarmelgy R.M., Thabet M.M., Jauniaux E. Prospective evaluation of impact of post-Cesarean section uterine scarring in perinatal diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorder. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022; 59(4): 474-82. https://dx.doi.org/10/1002/uog.23732.

- Sumigama S., Kotani T., Hayakawa H. Stepwise treatment for abnormally invasive placenta with placenta Pprevia. Surg. J. (N.Y.). 2021; 7(Suppl. 1):S20-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1728748.

- Шмаков Р.Г., Чупрынин В.Д., Приходько А.М. Способ органосохраняющего оперативного родоразрешения у пациенток с врастанием плаценты. Патент на изобретение RU 2706530 C1, 19.11.2019. Заявка №2019119188 от 20.06.2019. [Shmakov R.G., Chuprynin V.D., Prikhodko A.M. Method of organ-preserving surgical delivery in patients with placenta ingrowth. Patent for intervention RU 2706530 C1, 19.11.2019. Application №2019119188 dated 20.06.2019. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://patenton.ru/patent/RU2706530C1

- Altal O.F., Qudsieh S., Ben-Sadon A., Hatamleh A., Bataineh A., Halalsheh O. et al. Cervical tourniquet during cesarean section to reduce bleeding in morbidly adherent placenta: a pilot study. Future Sci. OA. 2022; 8(4): FSO789.https://dx.doi.org/10.2144/fsoa-2021-0087.

Received 04.10.2022

Accepted 07.03.2023

About the Authors

Maxim N. Umanskiy, PhD, Chief Physician, Rostov Regional Perinatal Center, +7(863)235-50-18, perinatal-rost@mail.ru, 344068, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Bodraya str., 90.Tatiana V. Khvalina, Head of the Department of Pregnancy Pathology, Rostov Regional Perinatal Center, +7(863)235-50-18, perinatal-rost@mail.ru,

344068, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Bodraya str., 90.

Alexander V. Bushtyrev, PhD, Head of the Maternity Department, Rostov Regional Perinatal Center, +7(863)235-50-18, bushtyr@gmail.com,

344068, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Bodraya str., 90.

Elizaveta V. Berezhnaya, 6th Year Student at the Faculty of General Medicine, Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

+7(928)774-88-43, liberezhnaya@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2242-8185, 344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakhichevan Lane, 29.

Corresponding author: Elizaveta V. Berezhnaya, liberezhnaya@yandex.ru