Prediction of placenta accreta associated with placenta previa

Pregnancy complicated by placenta previa is associated with a high risk of adverse outcomes, primarily with massive hemorrhage, which is largely due placenta accreta.Barinov S.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Beznoshchenko G.B., Kadtsyna T.V., Lazareva O.V., Bindyuk A.V., Neustroeva T.N., Stepanov S.S.

Aim. To determine prognostically significant risk factors for placenta accreta associated with placenta previa.

Materials and methods. Continuous sampling method was used to analyze the cases, when women had deliveries with placenta previa in history. The anamnesis data, birth outcomes, blood loss in patients with placenta accreta associated with placenta previa (n=117) and placenta previa without accretion (n=268) were compared.

Results. Placenta accreta occurred in 30.4% of women with placenta previa. Of them in 44.8% of cases, it was due to the presence uterine scars. Among the patients with placenta accreta, parity (p=0.039) and the number of births (p=0.001) was higher. In cases of abdominal delivery, 29.9% of women had obstetric hemorrhage. In patients with placenta accreta, the volume of blood loss was 3 times higher than in women without placenta accreta (p=0,001). The presence of an uterine scar after cesarean section was prognostically more significant in relation to placenta accreta associated with placenta previa (sensitivity — 93.2%, specificity — 76.5%).

Conclusion. The women with obstetric hemorrhage in cases of placenta previa are in a high-risk group for the development of massive hemorrhage. The presence of an uterine scar, more than two births in history, and delivery at ≥36.5 weeks are prognostic criteria for placenta accreta in pregnant women with placenta previa.

Keywords

Over the last decade, the number of pregnant women with placenta previa and placenta accreta has increased by 1.5 times. They are at risk for the development of massive obstetric hemorrhage, which undoubtedly affect maternal morbidity and mortality [1, 2].

At present, it is proved that with an increase in the number of abdominal deliveries in medical history, the risk of placenta accreta increases, and this pathology is associated with placenta previa in 75–90% of women. In the last decade, there has been an increase in postpartum hemorrhage from 6.1% to 8.3% in medical practice around the world. Maternal morbidity rate after postpartum hemorrhage increased from 0.18 to 0.23% [3].

There are many theories that consider the pathogenesis of placenta accreta from a variety of perspectives. The most common theory postulates that hypoxic factor with a reduced vascular component of scar tissue in the uterus is important, and to some extent explains the widespread prevalence of this pathology among women who previously underwent cesarean section [4]. Most publications and reports on clinical cases of placental accreta note a tight association of this pathology with the presence of a scar in the uterus after cesarean section and formation of uterine artery aneurysm in the lower segment. At the same time, there is convincing evidence of the direct association of the increased incidence of placenta accreta with the increased rate of caesarean sections. [5].

Postpartum hemorrhage is often associated with placenta previa and placenta accreta. Despite the introduction of high technologies and new methods of hemostasis, massive blood loss leading to hysterectomy is possible in pregnant women with placenta previa and placenta accreta [6]. Many people hold the opinion that currently there is no optimal method for managing severe postpartum hemorrhage. [7]. Therefore, the prevention of massive hemorrhage in cases of placenta previa and placenta accreta remains relevant, since the frequency of "near miss" events ("almost missed", or survived patients) are one order of magnitude higher than the number of deaths of patients whose health condition was characterized by somatic and mental morbidity [8].

Aim of study: to determine prognostically significant risk factors for placenta accreta associated with placenta previa.

Materials and methods

A retrospective bi-center case-control study was performed. Continuous sampling method was used to analyze the cases when women (n=385) had deliveries with placenta previa in history for the period 2013– 2019. The anamnesis data, birth outcomes, blood loss in patients with placenta accreta associated with placenta previa and placenta previa without accretion were compared. Among the studied patients with placenta accreta occurred with placenta previa 30.4% (117/385) of women were pregnant. The depth of invasion was the following: placenta accreta – in 50.4% (59/117), increta – in 48.7% (57/117), percreta – in 1.7% (2/117) of women.

Inclusion criteria: pregnancy with placenta previa. Exclusion criteria: extragenital diseases at the stage of decompensation, malignant neoplasms, developmental abnormalities of female reproductive organs.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2, STATISTICA 10, and SPSS-20 software packages. The distribution of the variation series was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. The distribution of variables in the compared groups differed from normal values. The data were presented as median (Me) and interquartile range between the 25th and the 75th percentiles – Me (Q1; Q3), as well as in absolute values and percentages (proportions). The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used for paired comparison of laboratory data. Criterion χ2 was used to compare the proportions. Identification of predictors of placenta increta (dependent variable/ response) among independent variables (laboratory and clinical data), assessment of their predictive value, and models building was performed using the classification tree method, ROC analysis and logistic regression. The null hypothesis was rejected taking into account the correction method for comparison of multiplicity [9].

Results

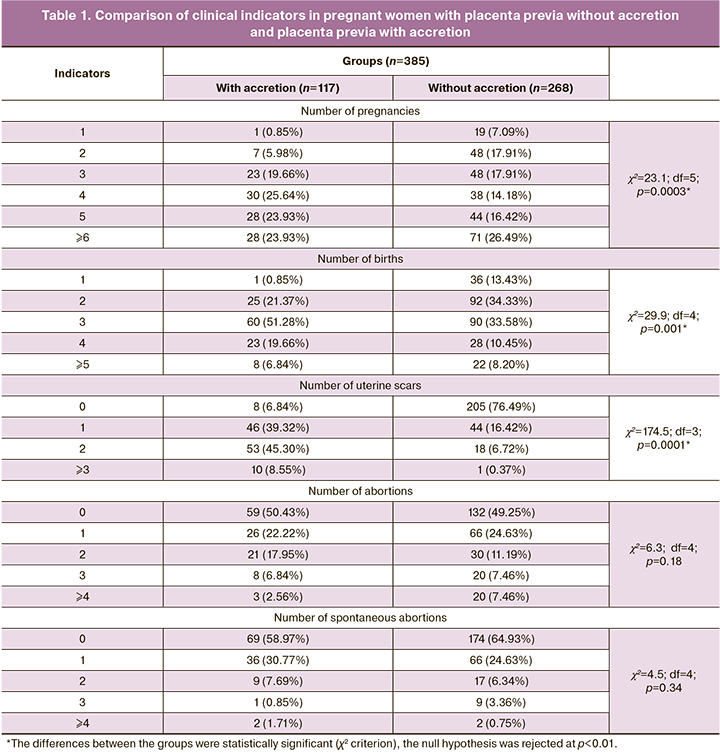

The comparison between pregnant women with placenta accreta associated with placenta previa and placenta previa without accretion showed statistically significant differences in clinical indicators. Pregnant women in the comparison groups were of a similar age. Among pregnant women with placenta previa, 5.2% (20/385) were primiparous, 94.8% (365/385) – secundiparous, and 21.0% (81/385) – multiparous women. In the group of pregnant women with placenta accreta associated with placenta previa, there were higher numbers of pregnancies, births and uterine scars per one patient (Table 1).

In this study, 50.4% (194/385) of women had abortions, 36.9% (142/385) of women had miscarriages. 44.7% (172/385) of women had cesarean sections in history. In the group of patients with placenta accreta, the number of cesarean sections in history (per one case) was significantly higher than in the group of patients without placenta accreta. Considering the number of abdominal deliveries, the observed patients were divided as follows: 23.4% (90/385) of pregnant women had to undergo the second cesarean section, 18.4% (71/385) – the third, and 2.9% (11/385) – the fourth and more cesarean sections.

The examined women had a high prevalence of chronic diseases. 77.4% (298/385) of pregnant women had at least one chronic disease, of them 55.6% (149/268) were the patients without placenta accreta, and 84.6% (99/17) with placenta accreta. When analyzing the intergroup differences among the patients with placenta accreta, there were significantly more cases of anemia (χ²=4.8; df=1; p=0.03), 58.6% (157/268) и 70.9% (83/117) accordingly. In pregnant women with placenta previa without accretion, varicose veins of the lower extremities were detected more often (χ²=5.6; df=1; p=0.018), 26.1% (70/268) и 14.5% (17/117) accordingly. According to the term of delivery, the patients with placenta previa were divided as follows: at 20–28 weeks – 4.2% (16/385), at 29–34 weeks – 29.9% (115/385), at 35–37 weeks – 32.7% (126/385) and at 37–42 weeks – 33.2% (128/385) of gestation. The decrease in the length of the gestation period among women with placenta accreta, compared to the group of women without placenta accreta, was due to the number of preterm births, to a greater extent at 32–36 weeks of gestation. Emergency delivery was performed in 30.9% (11/3859) of pregnant women with placenta previa mainly due to hemorrhage. Preoperative blood loss did not differ between the women with placenta previa without accretion and with accretion.

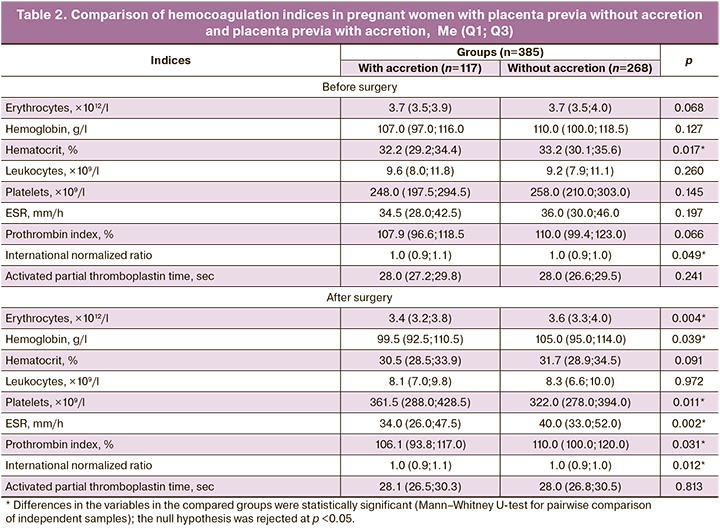

The volume of blood loss during abdominal delivery in women with placenta previa was up to 1.5 L – in 70.1% (270/385), from 1.5 L to 2.5 L – in 10.5% (40/385), more than 2.5 L – in 19.4% (75/385) of puerperas. Among the patients with placenta accreta, blood loss was higher compared to the group of women without placenta accreta (Mann–Whitney U-test, р<0,001), 2500 (1500; 4000) and 700 (500; 1000) ml accordingly. In 20.7% (80/385) of patients, intraoperative massive hemorrhage was noted. In 5.2% (20/385) of women, an injury to the bladder was recorded. In 5.2% (20/385) of women, continuous hemorrhage required hysterectomy. The analysis of intergroup differences in the state of platelet and plasma hemostasis revealed laboratory signs of acute posthemorrhagic anemia in patients with placenta accreta after cesarean delivery (Table 2).

The volume and composition of therapy aimed at restoration of hemovolemic conditions and correction of hemostatic parameters significantly differed in the studied groups. In total, 70.9% (273/385) of women received blood components transfusion. In the group of women with placenta previa with accretion, 96.6% (113/117) of patients needed red blood cell mass transfusion compared to 52.2% (140/268) of puerperas without placenta accreta (χ²=69.1; р<0.001).

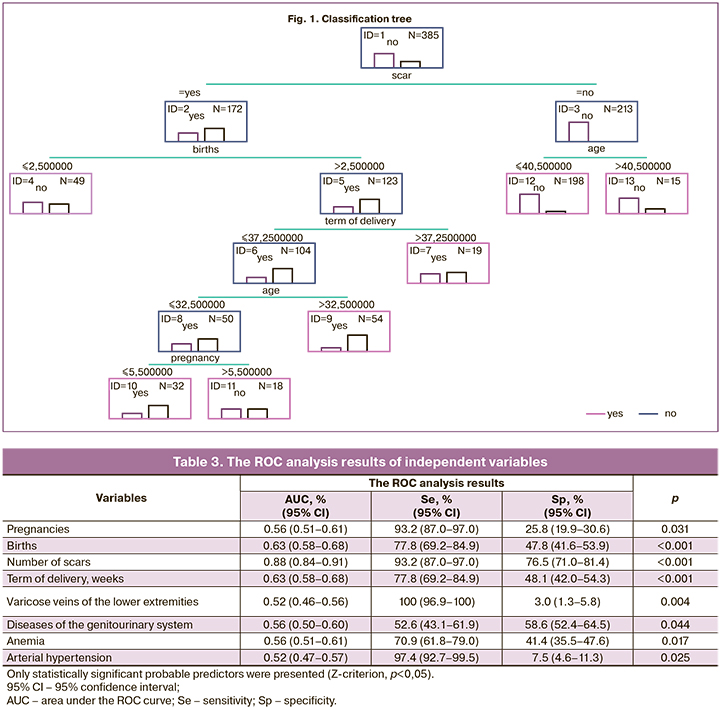

The selection of predictors to predict/classify placenta accreta (dependent variable, yes/no) among all studied independent variables was performed using the classification tree method, ROC analysis and logistic regression. These methods gave nearly the same, but not very similar results.

The classification tree method is a method of effective search for the relationship between predictor variables and categorical response (in this case, the occurrence of placenta accreta). It is ideally adjusted for graphical presentation of the classification results. According to this method, of 62 variables included in the database, only four had some value for predicting placenta accreta (yes/no). The presence of scars and births were the unambiguous signs of a high probability of placenta accreta (Fig.1).

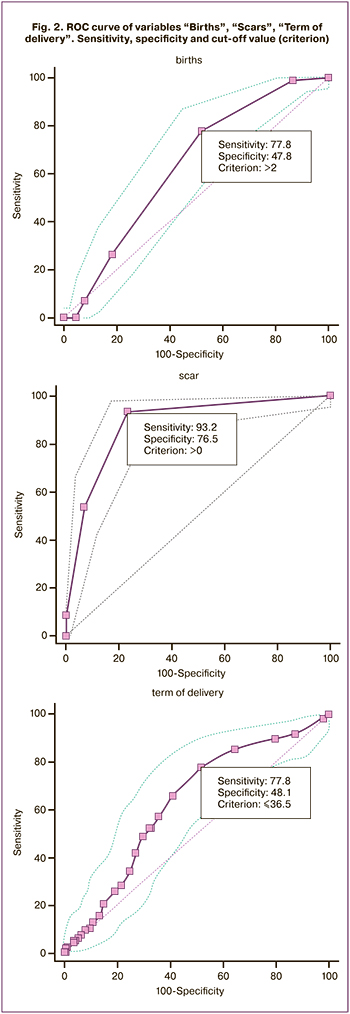

ROC analysis showed that among all studied independent variables, eight predictors of placenta accreta in pregnant women with placenta previa could be considered: 1) the number of pregnancies; 2) the number of births; 3) the number of uterine scars after cesarean section; 4) the term of delivery; 5) varicose veins of the lower extremities; 6) diseases of the genitourinary system; 7) anemia; 8) arterial hypertension (Table 3).

However, five variables among the detected ones (despite p <0.05) had a small AUC (area under the ROC curve), which indicated their insignificant strength. The strongest predictors were 1) the presence of uterine scar (cut-off value >0); 2) the number of births (cut-off value >2), and 3) the term of delivery. AUC=0.88, AUC=0.63 and AUC=0.63 respectively (Fig.2).

However, five variables among the detected ones (despite p <0.05) had a small AUC (area under the ROC curve), which indicated their insignificant strength. The strongest predictors were 1) the presence of uterine scar (cut-off value >0); 2) the number of births (cut-off value >2), and 3) the term of delivery. AUC=0.88, AUC=0.63 and AUC=0.63 respectively (Fig.2).

Thus, according to ROC analysis, the presence of the uterine scar, more than two births in history and term of delivery in women with placenta previa were more likely to be risk factors for placenta accreta among the given contingent of patients.

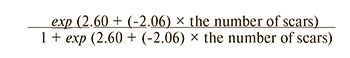

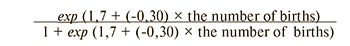

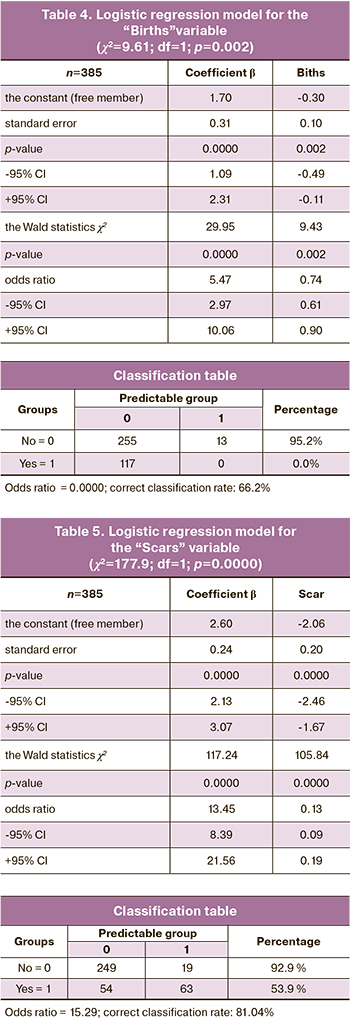

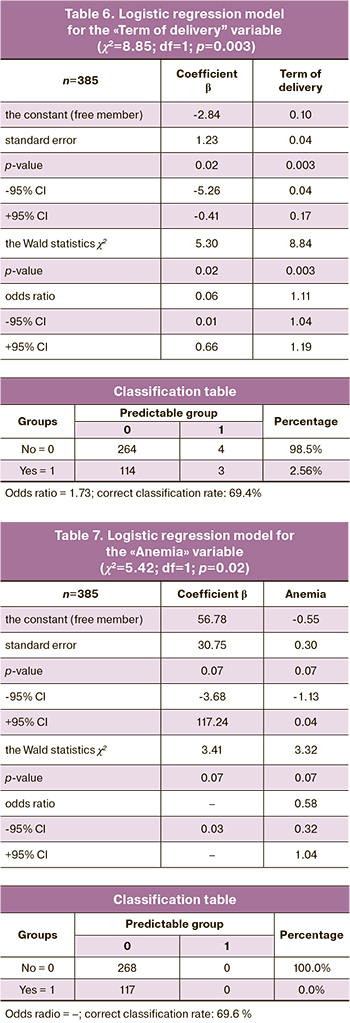

The results of two previous methods for selection of predictors among all studied variables were confirmed in conducting logistic regression, although there was no complete coincidence. It was found that out of all variables selected in the classification tree model and in ROC analysis, only four predictors could be considered real to a greater of lesser degree: 1) the number of scars; 2) the number of births; 3) the term of delivery and 4) anemia. Based on these data, simple one-component models for classification of pregnant women with placenta previa without accretion and with accretion were created (Tables 4−7). However, despite the statistical significance of the model with anemia (cThus, according to logistic regression data, the strongest predictive sign was the presence of scars (model for the “Scars”). This model had the highest coefficient − 2.06 (p<0.0001) and correctly classified the presence of accretion in 81.04% of cases (Table 5). Probability of accretion development (yes/ no) in a particular patient could be calculated using the logistic regression formula, in which the data were taken from the table:

It can be seen that, the more the number of scars was, the smaller probability was for a favorable pregnancy outcome (probability of placenta accreta was higher). For example, there was no uterine scar after cesarean section: 13.46/14.46=0.93; one scar: 1.72/2.72=0.63; two scars: 0.22/1.22=0.18; three scars: 0.03/1.03=0.03. Cut-off value (criterion) for this independent variable was > 0 scars. That is, the occurrence of even one scar sharply reduced probability for a favorable birth outcome due accretion in placenta previa and threat of hemorrhage.

Similarly, probability for a favourable outcome was estimated using the model for the “Births” (Table 4):

For example, nulliparous women: 5.47/6.47=0.85; parity: one birth: 4.1/5.1=0.80; two births: 3.3/4.3=0.76; three births: 2.2/3.2=0.69; four births: 1.65/2.65=0.62, five births: 1.22/1.32=0.55. The more the number of births was, the smaller probability was for a favorable pregnancy outcome (probability of placenta accreta was higher). Cut-off value (criterion) for this independent variable was >2 births. However, in this model, an increase in the number of births did not show sharp reduction of probability for a favourable outcome, as it was specific to an increase in the number of scars by one unit. From here it follows logically, that the scars more roughly and rapidly affected morphological and functional reorganization of the uterus compared to the births.

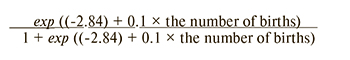

Also, probability for a favourable outcome was estimated using the model for the “Term of Birth” (Table 6):

For example, at 25 weeks: 0.72/1.72=0.42; at 35 weeks: 1.9/2.9=0.66; at 39 weeks: 2.9/3.9=0.74. The longer was the term of birth, the lower was the probability for a favorable pregnancy outcome. Cut-off value (criterion) for this independent variable was ≥36,5 weeks.

More sophisticated models for two or three variables using the logistic regression could not be built. This was due to the absence of strong or even medium correlation between the births, the number of scars and the term of delivery (statistically significant r-Spirment was not higher than 0.25). Probably, these factors (variables) were of independent importance in each particular woman and rarely could be combined.

Thus, the signs of scars, or more than two births, or deliveries at ≥36.5 weeks were probable independent factors in formation of placenta accreta. Three simple models the “Births”, “Scars” and “Term of delivery” were built. The practical use of the obtained models came down to the fact that in women with 2 or more births in history, who had uterine scars after cesarean section and who had delivery at ≥36.5 weeks, probability for a favorable pregnancy outcome decreases due to a high probability for placenta accretion associated with placenta previa. This should be taken into account in management of pregnancy and births in this contingent of patients. However, a particular woman may have only one factor, less often – two and very rarely – three factors. Each of these predictors is self-sufficient.

Discussion

Discussion

According to a number of authors, placental attachement to the anterior uterine wall in the presence of an uterine scar after cesarean section is a risk factor for placenta accrete and is directly correlated to several cesarean sections in anamnesis [10]. Our study based on sampling (n = 385) showed that 30,4% (95% CI: 25.8–35.3) of women had placenta accreta, and in 44,8% (95% CI: 39.8–49.9) of cases it was due to a scar in the uterus.

A number of authors are of the opinion, that in cases of obstetric hemorrhage due to placenta accreta, very often there are situations that require postpartum hysterectomy for saving women’s lives. Surgery in patients with placenta previa with accretion is always associated with a high risk of life-threatening complications, such as massive hemorrhage, injury to surrounding organs [6, 7]. According to the obtained data, in cases of abdominal delivery, 29.9% (95% CI: 25.4–34.8) women had obstetric hemorrhage with a risk of uncontrolled heavy postpartum hemorrhage. In patients with placenta accreta, the volume of blood loss was 3 times higher compared to puerperas without accretion of placenta previa.

Timely diagnosis of placenta previa and placenta increta is one of the most important components to prevent severe obstetric complications [5]. According to the results of our study, the parity (>2), the presence of uterine scar, delivery at ≥36,5 weeks were the predictors of placenta accreta associated with placenta previa. The most prognostically significant in relation to placenta accreta was the presence of a scar in the uterus after caesarean section (sensitivity – 93.2%, specificity – 76.5%).

Conclusion

Obstetric hemorrhage in women with placenta accreta associated with placenta previa is accompanied by a larger volume of blood loss than in women with placenta previa without accretion and is at high risk for the development of massive hemorrhage. Predictive criteria for placenta accreta associated with placenta previa in pregnant women were more than two births in history, the presence of an uterine scar after cesarean section, and delivery at ≥36.5 weeks. The strongest prognostic predictor was the presence of a scar in the uterus.

References

- Курцер М.А., Бреслав И.Ю., Григорян А.М., Кутакова Ю.Ю., Черепнина А.Л., Штабницкий А.М. Актуальные вопросы лечения послеродовых кровотечений в акушерстве. Медицинский алфавит. 2018; 1(9): 14-7. [Kurtzer M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Grigoryan A.M., Kutakova Yu.Yu., Cherepnina A.L., Shtabnitsky A.M. Topical issues of postpartum bleeding treatment in obstetrics. Medical alphabet. 2018; 1(9): 14-7. (in Russian)].

- D’Antonio F., Palacios-Jaraguemada J., Lim P.S., Forlani F., Lanzone A., Timor-Tritsch I. et al. Counseling in fetal medicine: evidence-based answers to clinical questions on morbidly adherent placenta. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 47(3): 290-301. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/uog.14950.

- Баринов С.В., Дикке Г.Б., Шмаков Р.Г. Баллонная тампонада матки в профилактике массивных акушерских кровотечений. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 8: 5-11. [Barinov S.V., Dikke G.B., Shmakov R.G. Balloon uterus tamponade in prevention of massive obstetric bleeding. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; 8: 5-11. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.8.5-11.

- Виницкий А.А., Шмаков Р.Г. Современные представления об этиопатогенезе врастания плаценты и перспективы его прогнозирования молекулярными методами диагностики. Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 2: 5-10. [Vinitskiy A.A., Shmakov R.G. The modern concepts of etiology and pathogenesis placenta accreta and prospects of its prediction by molecular diagnostics. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017; 2: 5-10. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.2.5-10.

- Цхай В.Б., Глызина Ю.Н., Яметов П.К., Леванова Е.А., Лобанова Т.Т., Грицаева Е.А., Чубко М.А. Предлежание и врастание плаценты в миометрий нижнего сегмента и цервикальный канал с наличием маточной аневризмы у беременных без рубца на матке. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 5: 194-9. [Tskhai V.B., Glyzina Yu.N., Yametov P.K., Levanova E.A., Lobanova T.T., Gritzaeva E.A., Chubko M.A. Placenta previa and increta into the lower segment myometrium and cervical canal with uterine artery aneurysm in pregnant women with no uterine scar. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; 5: 194-9. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.5.194-199.

- Dogan O., Pulatoglu C., Yassa M. A new facilitating technique for postpartum hysterectomy at full dilatation: cervical clamp. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018; 81(4): 366-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcma.2017.05.010.

- Chen J., Cui H., Na Q., Li Q., Liu C. Analysis of emergency obstetric hysterectomy: the change of indications and the application of intraoperative interventions. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2015; 50(3): 177-82.

- Серова О.Ф., Седая Л.В., Шутикова Н.В., Чернигова И.В., Климов С.В. Применение управляемой баллонной тампонады в комплексе лечения кровотечений во время операций кесарева сечения. Вопросы гинекологии, акушерства и перинатологии. 2016; 15(1): 25-9. [Serova O.F., Sedaya L.V., Shutikova N.V., Chernihiv I.V., Klimov S.V. The use of controlled balloon tamponade in the complex treatment of bleeding during cesarean section operations. Questions of gynecology, Obstetrics and Perinatology. 2016; 15(1): 25-9. (in Russian)].

- Боровиков В.П. Statistica: Искусство анализа данных на компьютере. 2-е изд. СПб.: Питер; 2003. 688с. [Borovikov V.P. Statistica: The art of data analysis on a computer. (2nd edition). St. Petersburg: Piter; 2003. 688p. (in Russian)].

- Tanaka M., Matsuzaki Sh., Matsuzaki S., Kakigano A., Kumasawa K., Ueda Y. et al. Placenta accrete following hysteroscopic myomectomy. Clin. Case Rep. 2016; 4(6): 541-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.562.

Received 03.09.2020

Accepted 20.11.2020

About the Authors

Sergey V. Barinov, MD, Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology №2, Omsk State Medical University.Tel.: +7(913)633-80-48. E-mail: barinov_omsk@mail.ru. ORCID: 0000-0002-0357-7097. 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin’s str., 12.

Irina V. Medyannikova, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology №2, Omsk State Medical University.

Tel.: +7(3812)24-06-58. E-mail: mediren@gmail.com. ORCID: 0000-0001-6892-2800. 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin’s str., 12.

Yuliya I. Tirskaya, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology №2, Omsk State Medical University.

Tel.: +7(3812)24-06-58. E-mail: yulia.tirskaya@yandex.ru. ORCID: 0000-0001-5365-7119. 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin’s str., 12.

Galina B. Beznoshchenko, MD, Professor, professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology №2, Omsk State Medical University.

Tel.: +7(3812)24-06-58. E-mail: akusheromsk@rambler.ru. ORCID: 0000-0002-6795-1607. 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin’s str., 12.

Tatyana V. Kadcyna, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology №2, Omsk State Medical University.

Tel.: +7(3812)24-06-58. E-mail: tatianavlad@list.ru. ORCID: 0000-0002-0348-5985. 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin’s str., 12.

Oksana V. Lazareva, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology №2, Omsk State Medical University.

Tel.: +7(3812)24-06-58. E-mail: lazow@mail.ru. ORCID: 0000-0002-0895-4066. 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin’s str., 12.

Alina V. Bindyuk, PhD, obstetrician-gynecologist of the Obstetric Physiological Department, Perinatal Center, Regional Clinical Hospital.

Tel.: +7(3812)24-13-58. E-mail: Alina1905@yandex.ru. 644111, Russia, Omsk, Berezovaya str., 3.

Tatyana N. Neustroeva, post-graduate student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology №2, Omsk State Medical University; Head of the Department of Gynecology, Perinatal Center, Sakha (Yakutia) Republican Hospital №1. Tel.: +7(964)418-35-32. E-mail: tatyananik1234@mail.ru.

677008, Russia, Yakutsk, Sergelyakhskoye highway, 4.

Sergey S. Stepanov, MD, Associate Professor, Senior laboratory assistant of the Department of Histology, Omsk State Medical University.

Tel.: +7(3812)28-41-33. E-mail: serg_stepanov@mail.ru. 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin’s str., 12

For citation: Barinov S.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya1 Yu.I., Beznoshchenko G.B., Kadtsyna T.V. , Lazareva O.V., Bindyuk A.V., Neustroeva T.N., Stepanov S.S. Prediction of placenta accreta associated with placenta previa.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 1: 61-69 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.1.61-69