Practical experience in the application of clinical guidelines «Enteral feeding of preterm infants»

Narogan M.V., Ryumina I.I., Kukhartseva M.V., Grosheva E.V., Ionov O.V., Talvirskaya V.M., Lazareva V.V., Zubkov V.V., Degtyarev D.N.

Appropriate nutrition is essential for the health and optimal growth of preterm infants. Aim. To investigate the effectiveness of the application of clinical guidelines "Enteral feeding of preterm infants" in infants below 32 weeks' gestation. Material and methods. The study comprised 114 extremely preterm infants born before (2013-2014, group 1, n=53) and after (2014-2015, group 2, n=61) introduction of the clinical guidelines. Comparative analysis included breastfeeding frequency, the time of initiation of enteral feeding and achieving enteral feeds up to a volume of 150ml/kg/d, the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), gastrointestinal dysfunction, gastric bleeding, the use of breast milk fortifier, and the dynamics of infant postnatal physical growth. A comparative assessment also included the length of hospital stay, postconceptional age (PCA) and body weight at the time of hospital discharge. Results. After the introduction of clinical guidelines, 47 (77%) children received maternal colostrum on the first day of life. Breastfeeding was initiated significantly earlier: within 1 (1-5) day after birth in group 2 compared with 9 (2-28) days in group 1. Most infants received enteral feeding on the first day of life, though the infants in group 2 were administered it significantly earlier [7.5 hours (3.5-51) vs. 12 (6-144)]. A significant part of the extremely preterm infants was fed with breast milk. Sixteen (30%) infants in group 1 and almost twice fewer children in group 2 [10 (16%)] were on artificial feeding. In group 2, full enteral feeding was achieved significantly earlier than in group 1 [12 days (6-48) vs. 18.5 (13-47)], while the incidence of NEC in group 2 decreased 1.7-fold (14.8% vs. 24.5%). By 36 weeks’ PCA, the infants in group 2 had significantly higher body weight than babies in group 1 [2220 g (1420-2818) vs. 2050 g (950-3190)]. Conclusion. The clinical implementation of the guidelines "Enteral feeding of preterm infants" has resulted in significantly higher feeding efficiency in extremely preterm babies.

Keywords

Achieving optimal growth and development of extremely preterm infants remains the utmost priority for clinicians and researchers. Appropriate nutrition is essential for the health and optimal growth of preterm infants [1]. Enteral feeding is preferred to total parenteral nutrition because the former avoids complications related to vascular catheterization, and numerous adverse effects of parenteral nutrition [1, 2]. Despite the declared principles of feeding, there are significant differences in the preterm enteral feeding practices not only in different countries but also in the different neonatal care department. Nevertheless, the priority is given to providing breast milk for feeding preterm babies, achieving a faster transition to full enteral nutrition and the standardization of nutrition schemes [1, 3-6].

Taking into account the results of research and clinical experience, in 2014 the Russian Society of Neonatologists developed and approved the clinical guidelines “Enteral feeding of preterm infants “, based on the priority of breast milk, early administration of colostrum and faster increase in enteral feeding volume, in contrast to those established in previous years of practice [7, 8]. Since the end of 2014, these clinical guidelines have been followed by the neonatal wards of the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P.

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of the application of clinical guidelines “Enteral feeding of preterm infants” in infants below 32 weeks’ gestation.

Material and methods

The study comprised 114 extremely preterm infants below 32 weeks’ gestation, who had very low birth weight (VLBW) and extremely low birth weight (ELBW), and were born in V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG & P.

The newborns were divided into two groups. Group 1 consisted of 53 infants (32 with VLBW, 21 with ELBW), born in 2013-2014 before the introduction of clinical guidelines; group 2 included 61 children (32 with VLBW, 29 with ELBW), born from 10.2014 to 10.2015 after the introduction of the clinical guidelines.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: hereditary metabolic diseases, endocrine diseases, severe hemolytic disease, and congenital malformations requiring early surgical correction.

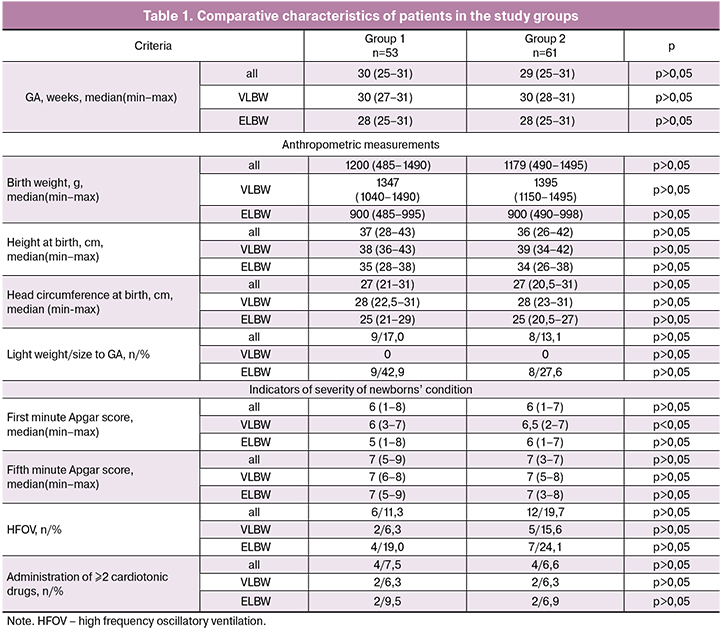

The groups were comparable in gestational age (GA), physical parameters at birth, and also in severity of the infant’s condition in the early neonatal life. A small difference was found in the first minute Apgar score among children born with VLBW (Table 1).

Comparative analysis included breastfeeding frequency, the time of initiation of enteral feeding and achieving enteral feeds up to a volume of 150ml/kg/d, the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), gastrointestinal dysfunction, gastric bleeding, practice in the use of breast milk fortifier, and the dynamics of postnatal physical development of extremely preterm infants. A comparative assessment also included the length of hospital stay (days), postconceptional age (PCA) and body weight at the time of hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis was carried out using nonparametric methods with the calculation of median, minimum and maximum [median (min-max)]. The Mann-Whitney test and χ2 were used to determine the differences between the variables. The relationship between the variables was determined using Kendall’s correlation coefficient (r). Reliability of correlation and differences between the variables was determined at a significance level p <0.05.

Results and discussion

Priority is given to providing breast milk to extremely preterm infants, and from the first day of life, they are administered colostrum 0.2ml buccally [2, 8, 9]. Before the introduction of clinical recommendations, colostrum was not given much attention, while in the second group 47 (77%) infants received buccal colostrum on the first day of life. Administration of buccal colostrum resulted in the significantly earlier initiation of breastfeeding in group 2, where it started from the 1st (1- 5) day of life compared with the 9th (2-28) day in group 1 (p <0.05).

Enteral nutrition started on the first day of life in 48 (90.6%) infants group 1 and 60 (98.4%) in group 2, but in group 2 it was initiated earlier, i.e., within 7.5 (3.5-51) hours, whereas in group 1 it started from 12 (6-144) hours (p <0.05). Previous studies have demonstrated the possibility and safety of starting enteral nutrition from 14 hours of life in children with VLBW and ELBW [10], whereas in our practice in 2015 it was initiated within the median time of 7.5 hours after delivery. These findings confirm the possibility of initiation of enteral nutrition on the first day of life in the majority of extremely preterm infants.

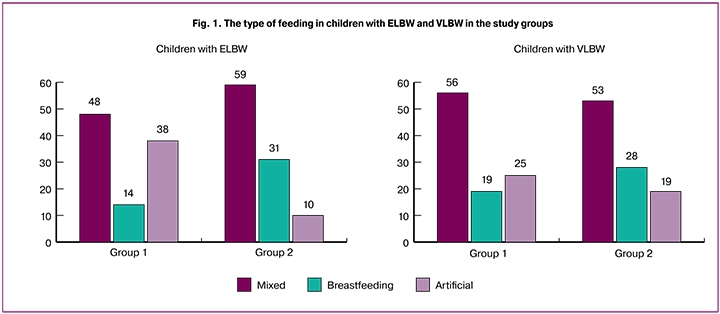

Most of the extremely preterm infants participating in the study were receiving breast milk before discharge from the hospital. It is important to note that in both subgroups of group 2, the proportion of children receiving breast milk was higher (Figure 1). Most of the extremely preterm infants were on mixed feeding. It should be noted that keeping mothers and babies together helped to achieve breastfeeding exclusively with breast milk (with a fortifier). Ten (16%) children group 2 and almost twice as many in group 1 - 16 (30%) - were on artificial feeding.

One of the significant barriers to breastfeeding preterm infants in our study was a maternal illness requiring treatment with medications not compatible with breastfeeding, which were administered to 4 (25%) and 5 (50%) women in groups 1 and 2, respectively. In other cases, psychosocial factors led to lactation failure. Thus, the introduction of clinical guidelines resulted in a 1.5-fold decrease in the proportion of modifiable risk factors for termination of breastfeeding.

An increase in the frequency of breastfeeding was achieved as a result of staff training, increased attention to breastfeeding and creating conditions for its implementation, such as the mandatory feeding of colostrum, encouraging mothers to regular milk expression, and daily practice of kangaroo mother care. Our experience confirms the results of other studies that have also shown the high efficacy of these simple methods of stimulating and maintaining lactation [11-14].

Infants in both groups who could not be breastfed received an infant formula for feeding preterm infants containing 2.3 to 2.67 g/100 ml of native or partially hydrolyzed cow’s milk protein.

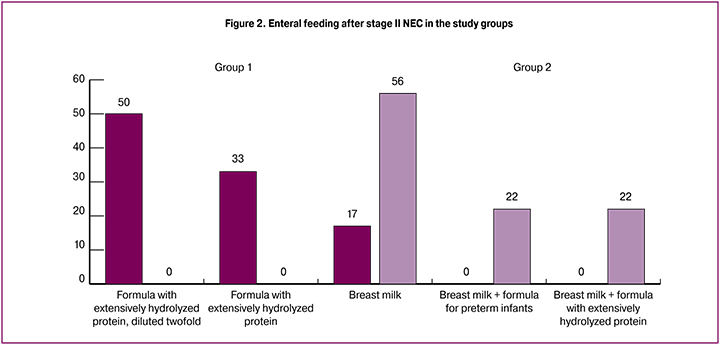

Infant formula based on the extensively hydrolyzed protein was administered to children who developed severe gastrointestinal dysfunction (n=2), recovering from NEC (n=12), and one child suspected of having galactosemia. In group 2, this infant formula was used in a significantly smaller percentage of babies than in group 1 [3 (4.9%) vs. 12 (22.6%) (p<0.05)] because of more often use of breast milk during the recovery from NEC.

It should be noted that the principles of enteral feeding after stage I or II NEC changed in the process of our study. In accordance with clinical guidelines, preterm infants in group 2 recovering from stage I and II NEC (n = 9) did not receive diluted of mixtures not provided for by the manufacturer, and the priority was given to breast milk. In group 2, supplementation of milk formula was provided to 4 (44%) children due to lack of breast milk. Meanwhile, infants in group 1, who were recovering from NEC (n = 12), predominantly received milk mixtures with extensively hydrolyzed protein [10 (83%)], including diluted ones (Figure 2). Our data are consistent with the majority of recommendations based on the primary use of breast milk during the recovery from NEC [15-17]. The findings showed that the use of breast milk allows effective reinitiation of enteral feeding in extremely premature infants after stage I and II NEC.

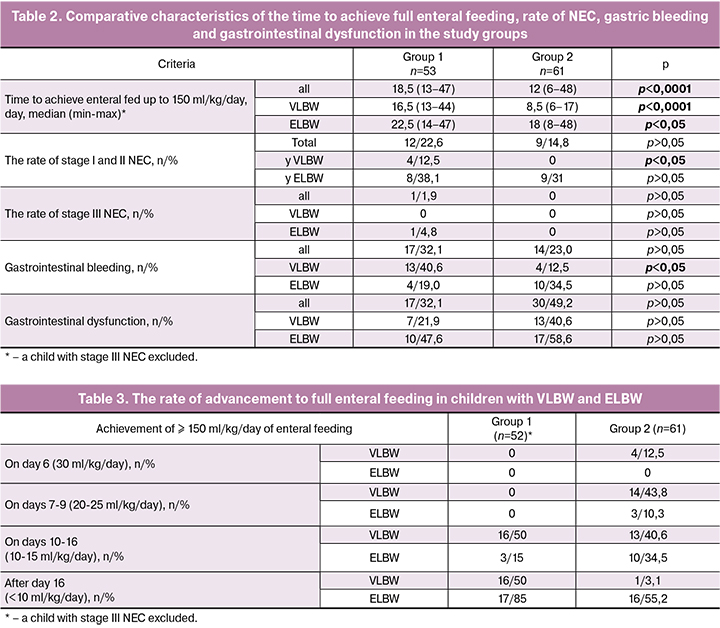

Adherence to clinical guidelines has led to a much earlier achievement of enteral feeds up to a volume of 150ml/kg/d against the background of a decrease in the incidence of NEC; particularly significant differences were noted among preterm infants with VLBW (Table 2). Despite contradictory opinions, available trial data suggest that advancing the volume of enteral feeds at a faster rate does not increase the risk of NEC [1, 4,18].

It should be borne in mind that feed tolerance depends on the type of nutrition product, i.e., the mother’s native milk, donor milk or various milk formulas. So, it is well known that breast milk has protective effects for preventing NEC in preterm infants [1, 4, 15, 19]. In our study, during the first 3-4 days of life, while the mother did not have enough milk, a milk formula was used along with the colostrum, but later the proportion of breast milk increased.

The rapid advancement of enteral feed volumes in group 2 has led to a decrease in the incidence of NEC, but was associated with a 1.5-fold increase in the number of gastrointestinal dysfunctions, which were defined as regurgitation and/or bloating, requiring a reduction in the volume or cessation of enteral feeding (Table 2).

Such gastrointestinal dysfunction was the reason for the decrease in the rate of enteral feeding advancement. If gastrointestinal dysfunction was successfully resolved by increasing feeding time using micro-jet instillation; in these cases, single feeding time could take from 60 to 90-120 minutes.

Gastric bleeding occurred mainly within the first week of life in 32.1% and 23% of newborns in group 1 and 2, respectively, and resulted in some delay in achieving full enteral nutrition (Table 2).

Thus, faster feed advancement proposed by the clinical guidelines yielded positive results in the form of earlier achievement of full enteral nutrition and a decrease in the incidence of NEC. However, this does not mean that in all cases it was possible to adhere to this scheme strictly. The condition of 14 (44%) children with VLBW in group 2 allowed the rates of feed advancement of no more than 15ml/kg/day. In more than half of the premature infants with ELBW, the rates of feed advancement were slower than 10 ml/ kg/day due to the development of gastric bleeding, gastrointestinal dysfunction and NEC (Table 3).

Current guidelines state that reaching full feeds in VLBW and ELBW infants is achievable within one and two weeks, respectively [1]. S.J. Molti et al. (2014) reported the achievement of full enteral feeds in infants with birth weight <1500 g by the 10-11th day of life (median), which is 1-2 days earlier than in our practice [20]. In other studies, the median time to reach full enteral feeds in VLBW and ELBW infants was 6-7 and 12 days, respectively [4, 21]. Thus, our findings suggest that in in the majority of children with VLBW included in our study the time to reach full enteral feeds was close to the recommended period. The practice of enteral feeding of preterm infants with ELBW also requires improvement and additional research, but it should be noted that unlike other studies, we did not exclude children with low Apgar scores, severe respiratory and hemodynamic disorders, and this could affect the tolerance to enteral feeding.

To meet the physiological needs of the extremely preterm infants, breast milk was fortified. In group 1 and 2, the fortification was used in 30 (56.6%) and 43 (70.5%) infants, respectively. The timing of the breast milk fortification initiation varied significantly in both groups. In group 2, breast milk fortification started significantly earlier than in group 1 [(14 (6-44) vs. 17.5 (10-50) day of life, p <0.05]; while the daily volume of enteral feeding at which the fortification began was significantly higher in group 2 (160 (99-200) vs. 125 (64-180) ml/kg, (p <0.05). These findings correspond with faster feeding advancement in group 2, where the fortifier was administered earlier and with greater feed volumes. The initial dose of the fortifier varied from 1/5 to full dose, both in group 1 and 2. Also in both groups, the full dose of the fortifier was achieved on average on day two after administration [2 (1-11) and 2 (1-15), respectively]. Administration of the fortifier was associated with regurgitation and/or bloating in 2 (7%) children of group 1 and 9% (21%) in group 2 (p <0.05). In these cases, the dose of the fortifier was decreased, or it was temporarily canceled, and to enrich the food, a partial supplementary milk formula for preterm infants was introduced. Thus, there is significant variability in the practice of administering the breast milk fortifier, which demonstrates the need for additional studies on safe and effective modes of prescribing breast milk fortification in extremely preterm infants.

The effectiveness of nutrition is assessed primarily by the parameters of the child’s physical development. Early optimal nutrition and postnatal growth play a key role in determining the short-term and long-term health of extremely preterm babies. The early delay in postnatal physical development is a serious problem for extremely preterm babies associated with worse survival, physical, neurological and cognitive development [4, 15, 22, 23].

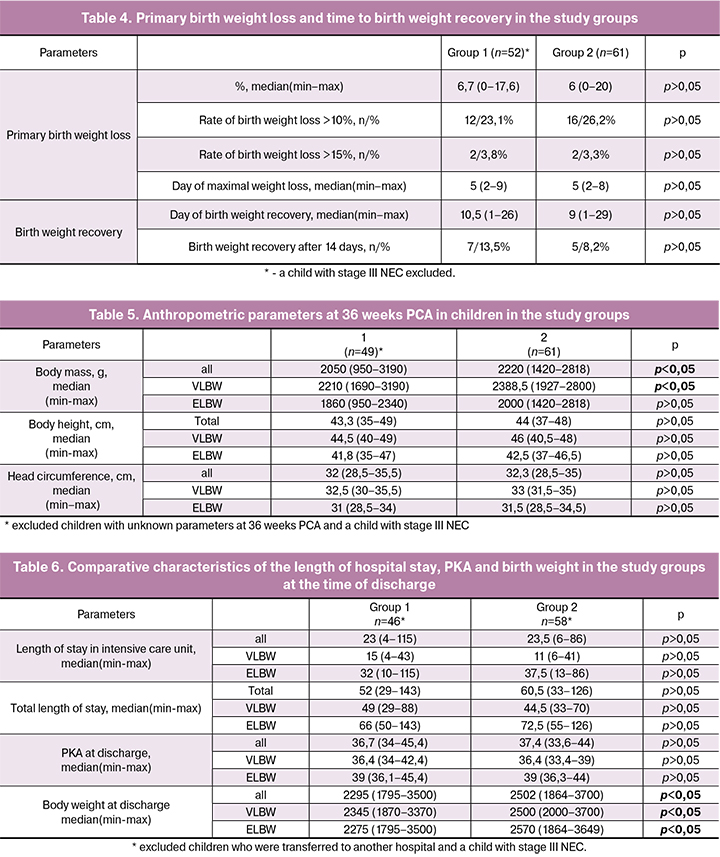

After birth, the majority of newborns experience birth weight loss as a result of the child’s adaptation to extrauterine life, which is characterized by a predominant loss of fluid. Since the early birth weight loss affects the baby’s growth and development in the first month of life, it deserves deserve closer attention in research and clinical practice. In preterm infants with ELBW and VLBW, birth weight loss up to 15% is considered permissible [22, 24, 25]. J.A. Roelants et al. reported that the birth weight loss in extremely preterm babies averaged 10.4%, and birth weight recovery occurred on average by the 11th day of life [22]. In our practice, the average birth weight loss was lower (6-6.7%) without significant difference between the study groups. In most children, birth weight loss did not exceed 15%. The infants in group 2 tended to faster birth weight recovery: on day 9 (1-29) vs. 10.5 (1-26). Also, the infants in group 2 less frequently recovered the birth weight later than the 14th day of life (Table 4).

Postnatal physical growth parameters (body weight, height, and head circumference) were evaluated at 36 weeks’ PGA. By that time, most of the extremely preterm babies were still in the hospital. By 36 weeks’ PGA, the body weight was significantly higher in group 2 than in group 1; there were no significant differences in the body height and head circumference; however, children in group 2 tended to have higher values (Table 5).

The change in the approaches to enteral nutrition did not affect the length of hospital stay both in the neonatal intensive care unit and in the neonatal hospital in general. Also, PGA at the discharge of extremely preterm infants was not affected. However, children began to be discharged home with significantly greater body weight (Table 6).

Conclusion

The clinical implementation of the guidelines “Enteral feeding of preterm infants” has resulted in significantly higher feeding efficiency in extremely preterm babies. The number of children receiving breast milk since the first day of life increased, full enteral nutrition was achieved earlier, the incidence of NEC declined, and there was an improvement in postnatal growth during the neonatal hospital stay.

References

- Dutta S., Singh B., Chessell L., Wilson J., Janes M., McDonald K. et al. Guidelines for feeding very low birth weight infants. Nutrients. 2015; 7(1): 423-42.

- Ionov O.V., Balashova E.N., Lenyushkina A.A., Kirtbaya A.R., Kukhartseva M.V., Zubkov V.V. Comparison of the two starting schemes - rapid and slow increase in enteral feeding in very low birth weight infants in intensive care units. Neonatologiya: novosti, mneniya, obucheniye. 2015; 4: 73-81. (in Russian)

- Klingenberg C., Embleton N.D., Jacobs S.E., O’Connell L.A., Kuschel C.A. Enteral feeding practices in very preterm infants: an international survey. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012; 97(1): F56-61.

- Uauy R., Koletzko B. Defining the nutritional needs of preterm infants. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 2014; 110: 4-10.

- Jasani B., Patole S. Standardized feeding regimen for reducing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: an updated systematic review. J. Perinatol. 2017; 37(7): 827-33.

- Ryumina I.I., Narogan M.V., Zubkov V.V., Koreneva O.A., Degtyarev D.N., Baibarina Ye.N. Organization of breastfeeding of newborns in the perinatal center (clinical recommendations). Neonatologiya: novosti, mneniya, obucheniye. 2017; 4: 149-60. (in Russian)

- Baibarina E.N., Degtyarev D.N., ed. Selected clinical guidelines for neonatology. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2016. 240p. (in Russian)

- Grosheva E.V., Ionov O.V., Lenyushkina A.A., Narogan M.V., Ryumina I.I. Enteral feeding of premature infants. In: Ivanov D.O., ed. Clinical recommendations (protocols) for neonatology. St. Petersburg: Inform-Navigator: 2016: 252-70. (in Russian)

- Cleminsona J.S., Zalewski S.P., Embleton N.D. Nutrition in the preterm infant: what’s new? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2016; 19(3): 220-5.

- Hamilton E., Massey C., Ross J., Taylor S. Early enteral feeding in very low birth weight infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2014; 90(5): 227-30.

- Maastrup R., Hansen B.M., Kronborg H., Bojesen S.N., Hallum K., Frandsen A. et al. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding of preterm infants. Results from a prospective national cohort study. PLoS One. 2014; 9(2): e89077.

- Parker L.A., Sullivan S., Krueger C., Kelechi T., Mueller M. Effect of early breast milk expression on milk volume and timing of lactogenesis stage II among mothers of very low birth weight infants: a pilot study. J. Perinatol. 2012; 32(3): 205-9.

- Morton J., Hall J.Y., Wong R.J., Thairu L., Benitz W.E., Rhine W.D. Combining hand techniques with electric pumping increases milk production in mothers of preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2009; 29(11): 757-64.

- Sharma D., Farahbakhsh N., Sharma S., Sharma P., Sharma A. Role of kangaroo mother care in growth and breast feeding rates in very low birth weight (VLBW) neonates: a systematic review. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017; Mar 27: 1-14.

- Patole S. Nutrition for the preterm neonate. A clinical perspective. Springer; 2013. 450p.

- Perks P., Abad-Jorge A. Nutritional management of the infant with necrotizing enterocolitis. In: Parrish C.R., ed. Nutrition issues in gastroenterology. Series 59: Practical gastroenterology. 2008; February: 46-60.

- Embleton N.D., Zalewski S.P. How to feed a baby recovering from necrotising enterocolitis when maternal milk is not available. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017; 102(6): F543-6.

- Oddie S.J., Young L., McGuire W. Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017; (8): CD001241.

- Patel A.L., Kim J.H. Human milk and necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2018; 27(1): 34-38.

- Moltu S.J., Blakstad E.W., Strømmen K., Almaas A.N., Nakstad B., Rønnestad A. et al. Enhanced feeding and diminished postnatal growth failure in very-low-birth-weight infants. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014;58(3): 344-51.

- Krishnamurthy S., Gupta P., Debnath S., Gomber S. Slow versus rapid enteral feeding advancement in preterm newborn infants 1000-1499 g: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Paediatr. 2010; 99(1): 42-6.

- Roelants J.A., Joosten K.F.M., van der Geest B.M.A., Hulst J.M., Reiss I.K.M., Vermeulen M.J. First week weight dip and reaching growth targets in early life in preterm infants. Clin. Nutr. 2017; Aug 31. pii: S0261-5614(17)30306-0.

- Ryumina I.I., Kirillova E.A., Narogan M.V., Grosheva E.V., Zubkov V.V. Feeding and postnatal growth of premature babies with intrauterine growth retardation. Neonatologiya: novosti, mneniya, obucheniye. 2017; 1: 98-107. (in Russian)

- Verma R.P., Shibli S., Fang H., Komaroff E. Clinical determinants and utility of early postnatal maximum weight loss in fluid management of extremely low birth weight infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2009; 85(1): 59-64.

- Adamkin D.H. Strategies for feeding infants with very low birth weight. Trans. from English. Baybarina E.N., ed. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2013. 176p. (in Russian)

Received 06.04.2018

Accepted 20.04.2018

About the Authors

Narogan Marina Viktorovna, Dr.Med.Sci., Leading Researcher at the Department of Pathology of Newborn and Premature Children, V.I. Kulakov NMRCfor OG & P of Minzdrav of Russia; Professor of Neonatology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University).

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: m_narogan@oparina4.ru

Ryumina Irina Ivanovna, Dr.Med.Sci., Head of the Department of Pathology of Newborn and Premature Children, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia. Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: 8 (903) 770-80-48. E-mail: i_ryumina@oparina4.ru

Grosheva Elena Vladimirovna, Ph.D., Deputy Head of the Department of Pathology of Newborn and Premature Children № 2 on clinical work, V.I. Kulakov

NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia. Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: e_grosheva@oparina4.ru

Ionov Oleg Vadimovich, Ph.D., Head of the Department of Neonatal Intensive Care, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia; Associate Professor

at the Department of Neonatology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University).

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: o_ionov@oparina4.ru

Kukhartseva Marina Vyacheslavovna, Neonatologist at the Department of Pathology of Newborn and Premature Children, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P

of Minzdrav of Russia; Ph.D. Student at the Department of Neonatology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University).

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: m_kukhartseva@oparina4.ru ; kolibry90@list.ru

Tal'virskaya Vasilisa Mikhailovna, Neonatologist at the Department of Newborn Children, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia;

Ph.D. Student at the Department of Neonatology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University).

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4.. E-mail: dr.vasilisa@gmail.com

Zubkov Viktor Vasil'evich, Dr.Med.Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Neonatology and Pediatrics, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia.

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: v_zubkov@oparina4.ru

Degtyarev Dmitrii Nikolaevich, Dr.Med.Sci., Professor, Deputy Director for Science, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia; Head of the Department of Neonatology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University). Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: d_degtiarev@oparina4.ru

Lazareva Valentina Vladimirovna, Ph.D. Student at the Department of Neonatology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University).

Адрес: 119991, Россия, Москва, ул. Трубецкая, д. 8, стр. 2. E-mail: l_tifi@mail.ru

For citations: Narogan M.V., Ryumina I.I., Kukhartseva M.V., Grosheva E.V., Ionov O.V., Talvirskaya V.M., Lazareva V.V., Zubkov V.V., Degtyarev D.N. Practical experience in the application of clinical guidelines "Enteral feeding of preterm infants".

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; (9): 106-14. (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2018.9.106-114