Uterine rudiments: clinical and morphological options of surgical treatment and its optimization

Objective. To optimize surgical treatment for complete or asymmetric aplasia of the uterus.Makiyan Z.N., Adamyan L.V., Asaturova A.V., Yarygina N.K.

Subjects and methods. A total of 95 patients with aplasia of the uterus and vagina, as well as with uterus unicornis were examined and operated on at the Department of Operative Gynecology, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, in the period f2016 to 2019. A complete clinical and laboratory examination, including ultrasound study of the pelvic organs and urinary system, was performed.

Results. Surgical treatment was performed according to patient complaints and the identified type of anomaly on the basis of clinical recommendations. Uterine rudiments during complete symmetric (aplasia of the uterus and vagina) and asymmetric (unicornuate uterus) malformations had a certain proliferative potential, as confirmed by clinical cases of growth and manifestation of functional activity; leiomyoma; and the presence of endometrioid heterotopias in the absence of eutopic (normal) endometrium.

Conclusion. To optimize surgical treatment, it is expedient to verify the clinical and anatomical options, to assess a risk for potential growth of pluripotent cells, and to expand indications for surgical removal of uterine rudiments in order to prevent complications.

Keywords

Uterine and vaginal aplasia corresponds to the earliest stage of embryonic morphogenesis and represents an extreme form of congenital underdevelopment of female reproductive organs [1–5].

Uterine and vaginal aplasia affects 1 out of 4000-5000 newborn girls. In most cases of full uterine aplasia, fallopian tubes and ovaries are normally developed (in the classic variant with a normal karyotype (46, XX); however, the vagina is also absent [3]. Surgical treatment is aimed at creating an artificial vagina (colpopoiesis) to restore sexual function [5–11]. Thanks to the advancements of assisted reproduction technologies, surrogacy or oocyte donation are possible [3, 11-14].

The unilaterally formed (unicornuate) uterus is an asymmetric variation of uterine malformation, which is more common in the population (approximately 1out of 1500–2000 newborn girls), and in 65% of cases, it co-occurs with unilateral renal agenesis. Patients with a unicornuate uterus have a favorable reproductive prognosis, because, in most cases, they are capable of becoming pregnant and giving natural vaginal birth [9–11, 15, 16].

Patients with full (symmetrical) uterine and vaginal aplasia and unicornuate uterus often have rudimentary horns or functional uterine rudiments. Optimal surgical management remains uncertain; most authors suggest surgical resection of a rudimentary horn only in the presence of functional activity or pain [1, 4–6, 14–16].

Analysis of our clinical material and literature showed inconsistency in identification and terminology, the ambiguity of surgical treatment, high rates of complications and repeat surgeries, and a lack of data on gynecological comorbidities in patients with a full uterine aplasia, unicornuate uterus, and uterine rudiments [2–5, 16–20].

This study was aimed to optimize surgical management of full or asymmetric uterine aplasia.

Materials and methods

From 2016 to 2019, 95 patients aged 18 to 39 years with uterine and vaginal aplasia (n=63) and a unicornuate uterus (n=32) underwent surgery at the Department of Operative Gynecology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia (table).

The preoperative evaluation consisted of a complete clinical and laboratory examination, including pelvic and urinary system ultrasonography.

The choice of surgery was based on patients’ complaints, the identified form of the anomaly, in compliance with the European Consensus and clinical guidelines for the provision of medical care, approved by Minzdrav of Russia.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia (protocol No. 9 dated November 22, 2018).

Results

Most of 35 patients with uterine and vaginal aplasia who underwent cytogenetic examination by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) had a normal female karyotype (46, XX), but 12.5% of them were found to have mosaicism of the X chromosome monosomy (45, X / 46, XX), which indicates the need for a genetic examination.

Sixty-three patients underwent peritoneal vaginoplasty and 26 patients had surgical resection of non-functional (n=13) and functional (n=13) uterine rudiments.

Macroscopically, bilateral uterine rudiments in all 63 patients with uterine and vaginal aplasia were represented by spindle-shaped muscle bundles located mesoperitoneally in lateral pelvic regions at the intersection of the round ligaments with the fallopian tubes and ovarian ligaments.

The following anatomical and morphological variations were identified:

- uterine rudiments without functional activity and endometrial cavity, which were represented by elongated spindle-shaped muscle bundles approximately 12-15 mm thick were identified in 50 patients;

- in 13 patients, uterine rudiments were represented by spindle-shaped muscle bundles about 3.5-4.0 cm long, 2.5-3.0 cm thick with a closed endometrial cavity about 6-8 mm in diameter; in 6 cases the cavities were expanded to 10-15 mm due to hematometra.

In most patients, ovaries had normal size and structure with preserved ovarian follicles. Twelve patients had polycystic ovaries with many primordial follicles (10–16) with smoothed and shiny tunica albuginea; the histological diagnosis was confirmed by ovarian biopsy.

In 13 patients, non-functional uterine rudiments were removed by surgical resection followed by peritoneal vaginoplasty. Indications for surgical resection of non-functional uterine rudiments were pain (n = 7) and the presence of endometriotic lesions (n = 6). Histological examination showed non- functional uterine rudiments represented by smooth muscle tissue (myometrium) about 10-12 mm thick. Spindle-shaped myocytes were arranged circularly, and some loci had abnormal myometrial architectonics. In the thickness of the myometrium, single endometrial glands were found, probably the rudiments of eutopic endometrium.

An analysis of the clinical variations of uterine and vaginal aplasia revealed signs of growth and functional activity in 12 (19%) patients.

Case 1

Patient G. had a history of peritoneal vaginoplasty for full uterine and vaginal aplasia at the age of 22 years when pelvic exploration showed uterine rudiments in the form of thin cords without signs of functional activity. At the age of 29 (7 years later), she developed recurring monthly lower abdominal pain and pelvic ultrasound showed an increase in sizes of uterine rudiments.

Laparoscopy revealed enlarged uterine rudiments with signs of functional activity, which were removed.

Histologic examination showed uterine rudiments seen as muscle strands; one of the sections had a cavity with a diameter of 3-4 mm, lined with a thin endometrium.

Many patients (39.7%) with uterine and vaginal aplasia had gynecological comorbidities, including endometriotic lesions of different locations that were found in 5 patients with non-functional and 12 patients with functional uterine rudiments. Multiple uterine fibroids were detected in 8 patients with non-functional uterine rudiments, including three patients with giant fibroids, and one patient underwent repeat surgery for recurrent uterine fibroids.

Case 2

Case 2

Patient A., 20 years old, presented with uterine and vaginal aplasia and non-functional rudimentary uterus in the form of cords (Fig. 1). Laparoscopy revealed extensive endometriotic lesions on the rectouterine peritoneum.

In 37.5% of cases, histological examination of uterine rudiments showed internal endometriosis, including in the absence of a eutopic endometrial cavity.

Case 3

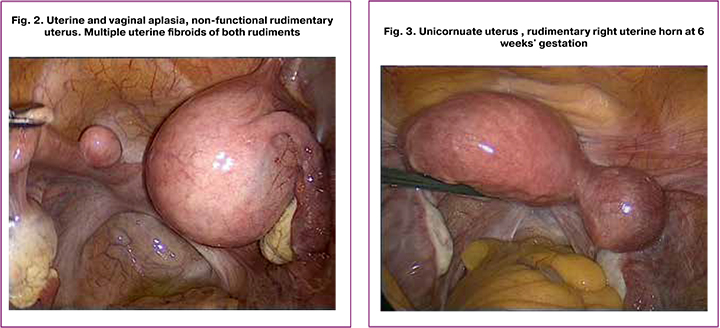

This observation is a unique case of a 41 years old patient M. with multiple uterine fibroids and uterine and vaginal aplasia. She had a history of laparoscopic peritoneal vaginoplasty with the removal of uterine rudiments and fibroids at the age of 24. Seven years later, she developed recurrent giant uterine fibroids, which were resected laparoscopically. Then at the age of 41, she underwent surgery for giant uterine fibroids with autologous red blood cell reinfusion (Fig. 2).

The unicornuate uterus was detected in 35 patients with the following morphological variations:

- unicornuate uterus with non-functional rudimentary horn (without endometrial cavity) - in 12 patients.

- unicornuate uterus with a rudimentary functional horn with a functional endometrial cavity - in 20 patients.

- a unicornuate uterus with a normal external contour, but the main horn communicates with the fallopian tube and cervical canal; laterally from the main functional horn, there is a rudimentary endometrial cavity, which is non- communicating or communicating with a unilateral Fallopian tube.

- a unicornuate uterus without a rudimentary horn and with a 5x8 mm thick muscular bundle in the area of confluence of the ovary’s ligament with the round ligament and the fallopian tube.

Twenty-three patients with a unicornuate uterus had unilateral renal agenesis (on the side of the rudimentary uterine horn).

Patients with a unicornuate uterus complained of pain of varying intensity linked with menstrual periods.

Patients with a unicornuate uterus regardless of the clinical picture underwent laparoscopic resection of the rudimentary horn with the subsequent morphological study.

During laparoscopy, the anatomical variation of the unicorn uterus was specified. To verify the diagnosis, hysteroscopy was performed, in which the uterine cavity of the fusiform shape and a single tubal ostium were found. Verification is necessary because the size of a rudimentary functional horn enlarged by hematometra may exceed the size of the main horn. After anatomical verification, the rudimentary uterine horn was grasped by the forceps and pulled as far as possible to the contralateral side away from the pelvic wall. Using a bipolar coagulator, the round uterine ligament, ovarian ligament and the uterine end of the tube were coagulated and transected sequentially. Anterior and posterior leaves of the wide uterine ligaments and the vesicoureteral peritoneal folds were dissected, the rudimentary horn was cut off, morcellated and removed through a 12 mm lateral trocar.

In two patients with non-communicating unicornuate uterus with a closed functional cavity of the rudimentary horn and normal external uterine contour (option “c”), the serous and muscle layers of the rudimentary horn were dissected, the functional endometrium of the rudimentary horn was completely excised, followed by layer-by-layer myometrial suturing. This technique allowed removal of a functional endometrium, which is the cause of acute pain, without opening the cavity of the main horn. A pregnancy with natural vaginal delivery may be planned six months after surgery.

Histological examination of the functional uterine horn revealed the presence of myometrial tissue and a cavity with the endometrial lining in the proliferation phase. The cervical canal and cervix are absent. The rudimentary horn consisted of myometrial tissue with randomly arranged muscle fibers. Muscle cells had signs of dystrophy, sometimes with mucoidosis and necrobiosis. There were signs of stage 1-2 internal endometriosis. Th e endometrium was represented by a basal layer with simple tubular glands.

Three patients had a heterotopic pregnancy in a rudimentary uterine horn.

Case 4

Patient K., 35 years old, presented with pregnancy at 5-6 weeks’ gestation (Fig. 3). She had a history of cesarean delivery at 38–39 weeks’ gestation when she was found to have a unicornuate uterus without a rudimentary horn (a rudimentary horn was presented as a thin cord). The patient had no pain during menstruations. The second pregnancy was spontaneous and desired. Ultrasound revealed a progressive pregnancy in the rudimentary right horn.

Laparoscopy showed unicornuate uterus measuring 6.0x5.5x5.5 cm, deflected to the left; on the right, there was a bluish rudimentary horn measuring 4.5x4.0x5.0 cm, expanded due to a fetal egg. The rudimentary right horn was removed; the edges of the main horn were sutured with immersing serous-muscular sutures.

Histological examination revealed a rudimentary uterine horn with a 7 mm thick intact myometrium; the cavity consisted of a decidualized endometrium and contained a fetal egg of early gestation.

Case 5

Patient G., 30 years old, was admitted urgently to the obstetric department at 32–33 weeks’ gestation and underwent emergency operative delivery for placental abruption. After a transverse suprapubic laparotomy, a lower uterine segment Caesarean section was performed. Internal iliac arteries were ligated. Blood loss was 2700 ml, and she received autologous red blood cell reinfusion. A dead fetus weighing 700 g from the left uterine hemi-cavity was born. Postoperative examination with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a pelvic ultrasound revealed a unicornuate uterus with a functional left uterine horn. The rudimentary horn measuring 4.0× 3.4×4.5 cm was slightly smaller than the main horn.

After laparoscopy (Fig. 4), the morphological version was verified (option “b”); the rudimentary left uterine horn was removed. Histologic examination showed that the rudimentary left horn consisted of the myometrium with foci of necrosis and calcification; some fragments were lined with hypotrophic endometrium (signs of gross dysplastic changes).

In three patients with a unicornuate uterus, who underwent several operations, there were difficulties in resecting the rudimentary horn due to atypical location.

Case 6

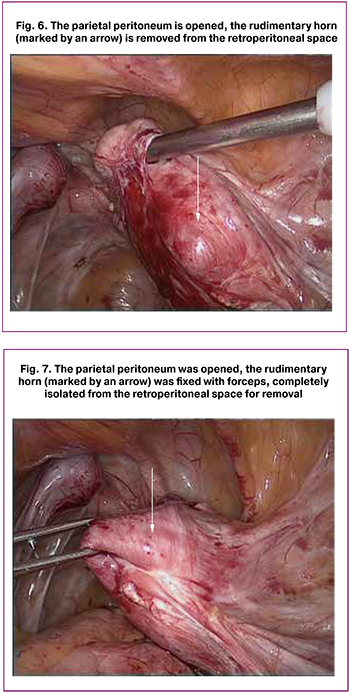

Patient N., 31 years old, had a history of monthly acute lower abdominal pain, which were more pronounced in the lower right abdomen since 14 years of age. At the age of 17, she was diagnosed as having a unicornuate uterus with a functional rudimentary right horn and right renal agenesis. She underwent five surgeries for severe pain; her right adnexa were surgically removed, she had two operations to remove the rudimentary horn. The pain syndrome persisted and she reported no pain relief with prescribed analgesics.

Laparoscopy (Fig. 5) showed extensive abdominal pelvic adhesions. Right adnexa were removed earlier. There were many endometrioid lesions on the parietal abdominal and pelvic peritoneum. The uterine body was small (3.5×4.0×4.0 cm), fusiform, deflected to the left and had a single fallopian tube. The left ovary, which was subtotally resected earlier, had the form of a whitish cord. The left fallopian tube was free throughout and had expressed fimbriae. On the right, between the internal and external iliac vessels in the retroperitoneal region, there was a rudimentary uterine horn measuring 5.0×4.5×6.0 cm, expanded due to dark hemorrhagic content (Fig. 6).

The round and infundibular pelvic ligaments on the right were coagulated, the peritoneum was opened, and the rudimentary uterine horn was isolated along the entire length sharply and bluntly (Fig. 7). At the lower pole, there was a fibrous cord with mucous content, apparently a rudimentary vagina. The right uterine vessels were coagulated, and the rudimentary horn was cut off and removed from the abdominal cavity by morcellation. Endometriotic lesions were coagulated by bipol

Conclusion

The findings of the study suggest the need for early diagnosis, verification of the anatomical variations of the aplastic uterus, and assessment of the potential for growth and proliferation of uterine rudiments. It is advisable to expand the indications for the removal of uterine rudiments in patients with functional rudiments identified by ultrasonography and Doppler ultrasound and in the presence of pain or gynecological comorbidities (uterine fibroids, external and internal endometriosis).

Optimization of surgical management strategy will allow timely prevention of severe complications and improve reproductive outcomes.

References

- Адамян Л.В., Курило Л.Ф., Глыбина Т.М., Окулов А.Б., Макиян З.Н. Аномалии развития органов женской репродуктивной системы: новый взгляд на морфогенез. Проблемы репродукции. 2009; 15(4): 10–9. [Adamyan L.V., Kurilo L.F., Glybina T.M., Okulov A.B., Makiyan Z.N. Anomalii razvitiya organov zhenskoi reproduktivnoi sistemy: novyi vzglyad na morfogenez. Problemy reproduktsii/Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2009; 15(4): 10–9. (in Russian)]

- Адамян Л.В., Богданова Е.А., Степанян А.А., Окулов А.Б, Глыбина Т.М., Макиян З.Н., Курило Л.Ф. Аномалии развития женских половых органов: вопросы идентификации и классификации (обзор литературы). Проблемы репродукции. 2010; 16(2): 7–15.[Adamyan L.V., Kurilo L.F., Okulov A.B., Bogdanova E.A., Stepanian A.A., Glybina T.M., Makiyan Z.N. Female reproductive organs’ anomalies: identification and classification (a review). Problemy reproduktsii/ Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2010; 16(2): 7–15.(in Russian)]

- Grimbizis G.F., Gordts S., Di Spiezio Sardo A., Brucker S., De Angelis C., Gergolet M. et al. The ESHRE/ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Hum. Reprod. 2013; 28(8): 2032–44. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det098.

- Makiyan Z. New theory of uterovaginal embryogenesis. Organogenesis. 2016; 12(1): 33-41. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15476278.2016.1145317.

- Окулов А.Б., Магомедов М.П., Поддубный И.В., Богданова Е.А., Файзулин А.К., Макиян З.Н., Глыбина Т.М., Смирнов В.Ф., Володько Е.А., Мираков К.К., Бровин Д.Н. Синдром Майера-Рокитанского-Кюстера-Хаузера у девочек, его варианты. Органосохраняющая тактика лечения. Андрология и генитальная хирургия. 2007; 8(4): 45–52. [Okulov A.B., Magomedov M.P., Poddubnyi I.V., Bogdanova E.A., Faizulin A.K., Makiyan Z.N., Glybina T.M., Smirnov V.F., Volod’ko E.A., Mirakov K.K., Brovin D.N. Sindrom Maiera-Rokitanskogo-Kyustera-Khauzera u devochek, ego varianty. Organosokhranyayushchaya taktika lecheniya. Andrologiya i genital’naya khirurgiya. 2007; 8(4): 45-52. (in Russian)]

- Макиян З.Н., Адамян Л.В., Быченко В.Г., Мирошникова Н.А., Козлова А.В. Функциональная магнитно-резонансная томография для определения кровотока при симметричных аномалиях матки. Акушерство и гинекология. 2016; 10: 73-9. [Makiyan Z.N., Adamyan L.V., Bychenko V.G., Miroshnikova N.A., Kozlova A.V. Functional magnetic resonance imaging for the determination of blood flow in symmetric uterine anomalies. Akusherstvo i ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynegology. 2016; (10): 73–9. (in Russian)] https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2016.10.73-9.

- Адамян Л.В., Фархат К.Н., Макиян З.Н. Комплексный подход к диагностике, хирургической коррекции и реабилитации больных при сочетании аномалий развития матки и влагалища с эндометриозом. Проблемы репродукции. 2016; 22(3): 84–90. [Adamyan L.V., Farkhat K.N., Makiyan Z.N. Comprehensive approach to the diagnosis, surgical correction and rehabilitation of patients with uterovaginal anomalies in combination with endometriosis. Problemy reproduktsii/ Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2016; 22(3): 84–90. (in Russian).]

- Acién P., Sánchez del Campo F., Mayol M.J., Acién M. The female gubernaculum: role in the embryology and development of the genital tract and in the possible genesis of malformations. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011; 159(2): 426–32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.07.040.

- Acién P., Acién M. Unilateral renal agenesis and female genital tract pathologies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2010; 89(11): 1424–31. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00016349.2010.512067.

- Acien P., Acien M. The history of female genital tract malformation classifications and proposal of an updated system. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2011; 17(5): 693–705. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmr021.

- Acién P., Acién M. The presentation and management of complex female genital malformations. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2016; 22(1): 48–69. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv048.

- Dragusin R., Tudorace S., Surlin V. Importance of laparoscopic assessment of the uterine adnexa in a Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome type II case. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2014; 40(2): 144–7. https://dx.doi.org/10.12865/CHSJ.40.02.13.

- Fletcher H.M., Campbell-Simpson K., Walcott D., Harriott J. Müllerian remnant leiomyomas in women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 119(2, Pt 2): 483–5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318242a9b5.

- Oppelt P.G., Lermann J., Strick R., Dittrich R., Strissel P., Rettig I. et al. Malformations in a cohort of 284 women with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH). Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012; 10: 57–64. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-10-57.

- Rousset P., Raudrant D., Peyron N., Buy J.N., Valette P.J., Hoeffel C. Ultrasonography and MRI features of the Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Clin. Radiol. 2013; 68(9): 945–52. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2013.04.005.

- Kawano Y., Hirakawa T., Nishida M., Yuge A., Yano M., Nasu K., Narahara H. Functioning endometrium and endometrioma in a patient with Mayer-Rokitanski-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Jpn. Clin. Med. 2014; 5: 43–5. https://dx.doi.org/10.4137/JCM.S12611.

- Makiyan Z. Endometriosis origin from primordial germ cells. Organogenesis. 2017; 13(3): 95–102. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15476278.2017.1323162.

- Venetis C.A., Papadopoulos S.P., Campo R., Gordts S., Tarlatzis B.C., Grimbizis G.F. Clinical implications of congenital uterine anomalies: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2014; 29(6): 665–83. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.09.006.

- Signorile P.G., Baldi A. Endometriosis: New concepts in the pathogenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010; 42(6): 778–80. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2010.03.008.

- Signorile P.G., Baldi F., Bussani R., D’Armiento M.R., De Falco M., Boccellino M., Quagliuolo L., Baldi A. New evidence sustaining the presence of endometriosis in the human foetus. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2010; 21(1): 142–7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.04.002.

Received 19.06.2019

Accepted 21.06.2019

About the Authors

Zohrab N. Makiyan, MD, Leading Researcher, Department of Operational Gynecology, Federal State Budgetary Institution National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after V.I. Kulakova “Ministry of Health of Russia. E-mail: makiyan@mail.ru; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0463-1913Leyla V. Adamyan, MD, academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, professor, head of the department of operative gynecology of the National Medical Research Center of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after V.I. Kulakova Ministry of Health of Russia. E-mail: aleyla@inbox.ru

Alexandra V. Asaturova, PhD, senior researcher of the pathomorphology department of the Federal State Budgetary Institution National Medical Research Center of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after V.I. Kulakova Ministry of Health of Russia.

Nadezhda K. Yarygina, applicant, Department of Operational Gynecology, Federal State Budgetary Institution National Medical Research Center of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after V.I. Kulakova Ministry of Health of Russia. Email: n.yarygina@gmail.com

For citation: Makiyan Z.N., Adamyan L.V., Asaturova A.V., Yarygina N.K. Uterine rudiments: clinical and morphological options of surgical treatment and its optimization.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; 12: 126-32. (In Russian).

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.12.126-132