Risk factors for vaginal delivery after cesarean section

Kuznetsova N.B., Ilуasova G.M., Bushtyreva I.O., Gimbut V.S., Pavlova N.G.

Objective: This study aimed to identify the risk factors associated with vaginal delivery in women who had previously undergone cesarean section. The analysis focused on clinical data and medical history as well as the course of pregnancy and labor. Materials and methods: Forty pregnant women with a uterine scar from a prior cesarean section who attempted vaginal delivery were included in this study. Based on the labor outcomes, they were divided into two groups. Group 1 comprised 26 women who underwent vaginal delivery, while group 2 consisted of 14 women who required repeat cesarean section during labor. A comparative analysis was conducted, taking into account clinical data, medical history, and the progression of index pregnancy and labor. Results: Patients in group 2 exhibited higher weight gain during pregnancy than those in group 1, with values of 12.5 [11, 16] and 10 kg [9; 14], respectively (p=0.045). Additionally, 30.8% of the women in group 1 had a history of previous vaginal deliveries, whereas no patients in group 2 had such a history (p<0.05). The placenta was more frequently located along the anterior uterine wall in group 1 (80.8%) than in group 2 (28.6%) (p=0.002). On admission to the maternity hospital, the minimum thickness of the lower uterine segment in the scar area, as determined by ultrasound, was greater in group 1 than in group 2, measuring 2.35 mm [2; 2.8] and 2.1 mm [1.95; 2.23], respectively (p=0.015). Moreover, women in group 1 were significantly more likely to be admitted with a mature cervix according to the Bishop scale than those in group 2 (p=0.007). The dilation of the internal os was twice as wide in group 1 versus group 2 (p=0.002). Rupture of membranes occurred at term more frequently in group 1 than in group 2 (p=0.03). Conclusions: Based on our findings, risk factors associated with an unsuccessful attempt at vaginal delivery after cesarean section include a lower uterine segment thickness ≤2.1 mm upon admission, cervical maturity score ≤5 points according to the Bishop scale, dilation of the internal os ≤2 cm upon admission, and early rupture of membranes.

Authors' contributions: Kuznetsova N.B., Ilyasova G.M., Bushtyreva I.O., Pavlova N.G. – conception and design of the study; Kuznetsova N.B., Ilyasova G.M., Gimbut V.S. – data collection and processing; Ilyasova G.M. – drafting of the manuscript; Kuznetsova N.B., Pavlova N.G. – editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation Kuznetsova N.B., Ilуasova G.M., Bushtyreva I.O., Gimbut V.S., Pavlova N.G. Risk factors for vaginal delivery after cesarean section. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (10): 78-85 (in Russian) https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.121

Keywords

Obstetricians and gynecologists are concerned about the rate of cesarean sections (CS), which is increasing year by year. The concept of "once a cesarean, always a cesarean," which was once widely accepted, has led to the challenge of managing pregnancy and labor in women with two or more uterine scars. This issue encompasses both medical and socioeconomic considerations. According to the clinical guidelines of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (MH RF) (2020), the presence of a uterine scar after one CS is not an absolute indication for repeat CS [1]. However, previous CS remains a primary indication for subsequent CS [2, 3]. Consequently, there has been an increase in the number of women with two or more uterine scars planning future pregnancies. As a result, serious obstetric complications such as pregnancy in the scar, placenta previa, placenta accreta spectrum, uterine ruptures, and obstetric bleeding, posing a direct threat to the life of both mother and fetus, become inevitable [4–6].

A globally recognized approach to reducing the incidence of recurrent CS is to manage labor in women with uterine scars through vaginal delivery [7–11]. One of the key prerequisites for conservative management of such deliveries is the integrity of the uterine scar. This pertains not only to its anatomical integrity but also its functional integrity. The widely used ultrasound assessment of uterine scars during pregnancy currently allows visual confirmation of the absence of a myometrial defect and measurement of its residual thickness in the scar area. However, the absence of signs of uterine scar defects according to ultrasound does not guarantee that the scar will remain intact during labor. Although ultrasound evaluation of the scar during pregnancy plays a significant role in selecting an ideal candidate for vaginal delivery, it does not predict its successful course [12]. According to the clinical guidelines of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (2021), the thickness of the lower segment measured before the onset of labor is not crucial for the trial of labor after cesarean delivery and may not be measured in the absence of other signs of uterine scar defects (such as irregular critical thinning of the uterine scar area with signs of deformity and pain upon pressing with a transvaginal ultrasound probe) [7].

This study aimed to identify the risk factors for vaginal delivery in women with uterine scars after a previous CS based on the analysis of clinical data, medical history, pregnancy, and labor.

Materials and methods

Forty pregnant women with uterine scar after one CS were included in the study. The inclusion criteria for the study were singleton premature pregnancy, fetal head presentation, previous CS performed by transverse incision of the lower uterine segment, adequate uterine scar according to ultrasound (according to the Clinical Recommendations of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 2021 [7]), localization of the placenta outside the uterine scar, absence of concomitant indications for repeated CS, intergenic interval of more than 2 years, women’s desire for vaginal delivery, spontaneous onset of labor, and informed consent to participate in the study.

All the women were scheduled to undergo vaginal delivery. On admission to the maternity hospital, all women were clinically evaluated for uterine scarring by palpating the area of the postoperative scar and ultrasound, recording the minimum thickness of the lower uterine segment in the area of the presumed scar. Ultrasound was performed on a VOLUSON E10 device using a RAB 6-D convex transducer and an RIC 6-12-D vaginal transducer.

During a vaginal examination, the opening of the internal os and the degree of cervical maturity were assessed according to the Bishop scale (1964), as modified by J. Burnett (1966) were assessed according to the following parameters: consistency of the cervix; cervical length, cervical effacement; patency of the cervical canal, cervical os; position of the cervix.

Based on labor outcomes, the patients were divided into two groups. Group 1 comprised 26 women who underwent vaginal delivery, while group 2 consisted of 14 women who required repeat cesarean sections during labor. A comparative analysis was conducted, considering clinical data, medical history, and the progression of index pregnancy and labor.

Statistical analysis

Data collection and database generation were performed in MS Excel 2019 (Microsoft, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics software (version 26.0; IBM Statistics, USA). The normality of the distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test because the sample size was <50 in both groups). Continuous variables were described using median (Me), lower (25%), and upper (75%) quartiles [Q1–Q3]. In addition, the difference between groups 1 and 2 was calculated for each quantitative parameter: =х2-х1, where х1 is the parameter in group 1 and х2 is the parameter in group 2. The 95% confidence interval (CI) for differences was also calculated. Categorical data are presented as counts and percentages (%). Normally distributed continuous variables with equal variance were compared between the two groups using Student’s t-test for independent samples. A nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare numerical data with a non-normal distribution for independent samples. Proportions of categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test (when the expected frequencies were < 10). Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

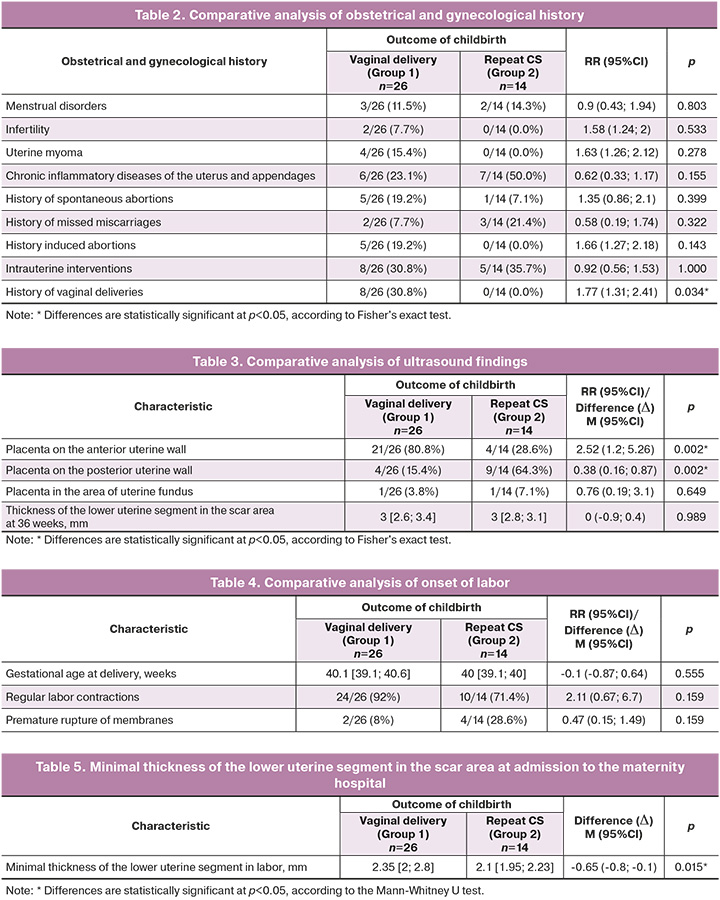

All women were comparable in age, height, intergenic interval, baseline body mass index (BMI), and BMI at the time of delivery (Table 1). The age of the women in group 1 was 32 [30;33] years, and that of the women in group 2 was 30 [28;33] years, p=0.318. The height of the women in group 1 was 165 [163;170.5] cm, and in group 2, 164 [159.5;168] cm, p=0.234. The intergenic interval was 3.5 [3;7.2] years in group 1 and 4 [3;5] years in group 2 (p=0.761). The baseline BMI was 21 [19.5;24.3] kg/m2 in group 1 and 21.8 [20.3;24.2] kg/m2 in group 2 (p=0.995). BMI at delivery was 26.3 [23.4;29] kg/m2 in group 1 and 27.3 [25.4;28] kg/m2 in group 2 (p=0.469). The highest weight gain during pregnancy was observed in women with a failed vaginal delivery attempt (group 2), 12.5 [11;16] kg, and 10 [9;14] kg in group 1 (p=0.045).

When analyzing the obstetrical and gynecological history of women in the studied groups, no differences were found in the frequency of menstrual disorders, infertility, uterine myomas, presence of chronic inflammatory diseases of the uterus and appendages, spontaneous abortions, undeveloped pregnancies, induced abortions, and intrauterine interventions in the history (Table 2).

Differences were found in the number of vaginal deliveries in the past history (before or after primary CS). Almost one-third of group 1 women (8/26, 30.8%) had a history of vaginal delivery, whereas group 2 patients had no history of vaginal delivery, p˂0.05.

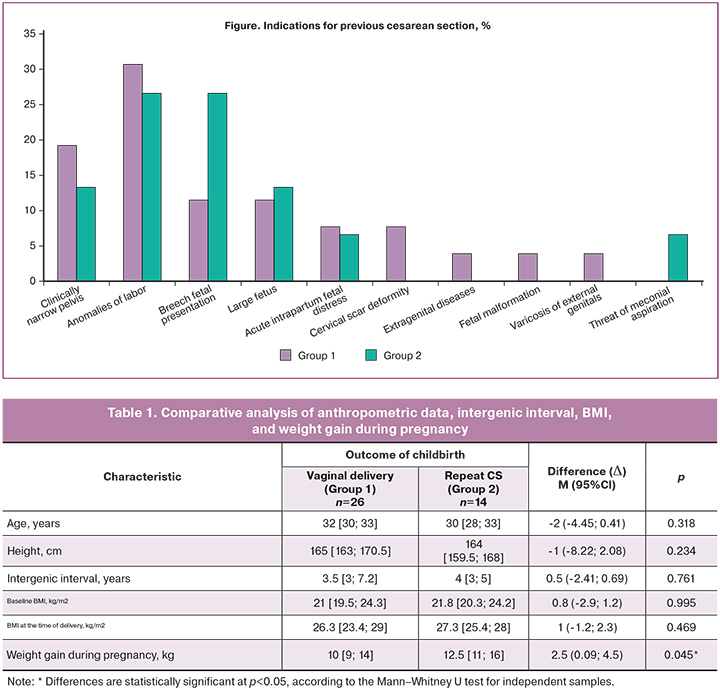

The indications for previous CS in patients in the study groups were analyzed (Figure). A clinically narrow pelvis was an indication for primary CS in 5/26 (19.2%) women in group 1 and 2/14 (14.3%) women in group 2 (p=1.000); anomalies of labor in 8/26 (30.7%) women in group 1 and 4/14 (28.6%) women in group 2 (p=1.000); fetal breech presentation in 3/26 (11.5%) women in group 1 and 4/14 (28.6%) women in group 2, p=0.214; large fetus in 3/26 (11.5%) women in group 1 and 2/14 (14.3%) women in group 2, p=1.000; acute intrapartum fetal distress in 2/26 (7.7%) women in group 1 and 1/14 (7.1%) women in group 2, p=1.000.

Among the indications that occurred only in group 1 women were cervical scar deformity, 2/26 (7.7%), p=0.533; cardiovascular disease of the pregnant woman (according to the cardiologist's opinion), 1/26 (3.9%), p=1.000; congenital malformations of the fetus, 1/26 (3.9%), p=1.000; and external genital varices, 1/26 (3.9%), p=1.000. Among the indications occurring only in group 2, women were threatened with meconium aspiration (1/14 [7.1 %], p=0.350).

At 36 weeks of gestation, all patients underwent measurement of the minimum thickness of the lower uterine segment in the scar area and identification of the location of the placenta (Table 3). It was found that in group 1, the placenta was more often located along the anterior uterine wall (21/26 [80.8 %]) than in group 2 (4/14 [28.6 %], p=0.002). In group 2, the placenta was more often located along the posterior uterine wall, 9/14 (64.3%) than in group 1 (4/26 [15.4 %], p=0.004). The location of the placenta in the area of the uterine fundus was comparable between group 1 and 2. There were no differences in the minimum thickness of the lower uterine segment in the scar area between women in groups 1 and 2 (3 [2.6; 3.4] mm and 3 [2.8; 3.1] mm, respectively, p=0.989).

To determine the role of infectious factors in failed attempts of vaginal delivery after CS, the incidence of infectious diseases of the genital tract, acute respiratory diseases, and frequency of exacerbation of chronic infections during pregnancy were analyzed. Genital tract infections and acute respiratory diseases during pregnancy occurred in women in groups 1 and 2 with equal frequency (p1=0.071 and p2=1.000, respectively). No exacerbation of chronic diseases was detected in the women in either group.

To assess the course of labor, the following indicators were analyzed: gestational age at the time of the onset of labor, the nature of the onset of labor, the minimum thickness of the lower segment of the uterus in the scar area upon admission to the maternity hospital, and the degree of maturity of the cervix according to the Bishop scale (1964) as modified by J. Burnett (1966) upon admission to the maternity hospital, opening of the internal os upon admission to the maternity hospital, degree of opening of the uterine os upon rupture of membranes, method of pain relief during labor.

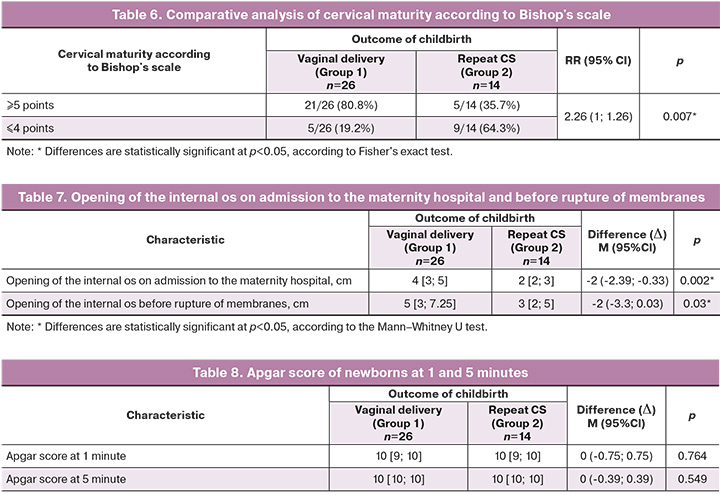

The gestational age at the time of onset of labor activity in women in groups 1 and 2 was comparable: 40 weeks 1 day [39.1; 40.6], 40 weeks [39.1; 40], p=0.555. A total of 24/26 (92%) women in group 1 were admitted to the maternity hospital with regular labor contractions; 2/26 (8%) had premature rupture of membranes. In group 2, 10/14 (71.4%) women had regular labor contractions, and 4/14 (28.6%) had premature rupture of membranes (p=0.159) (Table 4).

The minimal thickness of the lower uterine segment in the scar area according to the ultrasound data at admission to the maternity hospital was greater in group 1 women than in group 2 women and amounted to 2.35 [2;2.8] mm; in group 2 women, 2.1 [1.95;2.23] mm, p=0.015) (Table 5).

The degree of cervical maturity according to the Bishop scale in 21/26 (80.8%) women in group 1 was ≥5 points ("mature" cervix) and in 5/26 (19.2%) was ≤4 points ("insufficiently mature", "immature" cervix). In group 2 women, the cervical maturity according to the Bishop scale ≥5 points ("mature" cervix) was observed in 5/14 (35.7%), ≤4 points ("insufficiently mature", "immature" cervix) in 9/14 (64.3%), p=0.007 (Table 6).

The opening of the internal os at admission to the maternity hospital in group 1 women was 2 times larger than that in group 2 women and amounted to 4 [3;5] cm; in group 2 women, 2 [2;3] cm, p=0.002. Differences in uterine os opening before rupture of membranes were also revealed. In women in group 1, the rupture of the membranes occurred at term, and the opening of the uterine os at the time of rupture of the membranes was 5 [3;7.25] cm; in group 2 women, early rupture of membranes was observed, the opening of the uterine os at rupture of membranes was 3 [2;5] cm, p=0.03 (Table 7).

There were no statistically significant differences in the frequency of epidural analgesia in labor in the compared groups: 19/26 (73.1%) women in group 1 and 9/14 (64.3%) women in group 2 received epidural analgesia (p=0.720).

The neonatal birth weights in groups 1 and 2 were 3580 [3375;3700] g and 3558 [3404;4032] g, respectively, p=0.136). The Apgar scores of the newborns at 1 and 5 min were comparable between groups 1 and 2 (Table 8).

Discussion

There is genuine interest in the topic of vaginal delivery for women with uterine scars after previous cesarean sections, driven by the desire to minimize the risks associated with repeat abdominal deliveries. Repeated abdominal deliveries elevate the risks of injury to adjacent organs, obstetric bleeding, thromboembolic complications, septic complications, and pelvic adhesions [2, 7, 12, 13]. Maternal morbidity and mortality rates are higher with repeat cesarean section than with vaginal deliveries after C-sections [7]. Subsequent pregnancies increase the risk of placenta previa, abnormally invasive placenta, uterine scarring, and uterine rupture [4-6]. Therefore, the approach to labor management in women with uterine scars after cesarean sections should be determined after careful consideration of the potential benefits and risks of both attempted vaginal delivery with a uterine scar and repeated cesarean sections. While successful vaginal delivery offers more benefits than risks, it is important to acknowledge the primary risk of uterine rupture, which poses a direct threat to the lives of both the mother and fetus. This explains the mixed opinions of specialists regarding attempted vaginal delivery in women with uterine scars.

To date, the criteria for selecting the so-called "ideal candidate" for attempted vaginal delivery after a C-section based on anamnestic data and ultrasound assessment of the uterine scar have been extensively studied. The stability of the uterine scar on ultrasound, as determined by the minimum thickness of the lower uterine segment in the scar area during pregnancy, is one of the criteria for selecting a candidate for attempted vaginal delivery after a cesarean section. However, the question remains as to what thickness of the uterine scar should be considered the boundary between normal and abnormal. However, a consensus on this issue has not yet been reached. Undoubtedly, the reparative process after surgical intervention plays a crucial role; the morphological and functional integrity of the scar will depend on how well it has healed. Parameters of vascular resistance in radial arteries were proposed as a possible diagnostic criterion for assessing the intensity of reparative angiogenesis by Pavlova N.G. et al [14]. However, a scar that appears solid according to ultrasound data obtained before labor may prove to be less stable during the delivery process. Therefore, it is pertinent to further study the minimum thickness of the lower uterine segment in the area of the presumed scar at the onset of labor activity, as well as to explore various biochemical markers of morphological scar integrity.

According to Petrova et al. (2012), a mature and soft birth canal is one of the clinical markers of morphofunctional integrity of the uterine scar after a cesarean section and is a favorable factor in predicting successful natural delivery [15]. Our results are consistent with those of that study.

Conclusion

Intrapartum factors play a pivotal role in predicting the likelihood of vaginal delivery failure after cesarean section. With a functionally complete scar, labor initiates spontaneously with regular contractions at biological maturity of the cervix.

Factors such as the thickness of the lower uterine segment in the scar area upon admission to the hospital (≤2.1 mm), cervical maturity on the Bishop scale (≤5 points), internal os opening upon admission to the hospital (≤2 cm), and early rupture of membranes can be considered risk factors for failed trial of vaginal delivery after cesarean section.

The significant differences in placental location according to ultrasound findings between women with successful and failed trial of labor of vaginal delivery after cesarean section are of great scientific interest and warrant further research.

References

- Российское общество акушеров-гинекологов (РОАГ), Ассоциация акушерских анестезиологов-реаниматологов (АААР). Роды одноплодные, родоразрешение путем кесарева сечения. Клинические рекомендации. 2020. [Russian Society of Obstetricians-Gynecologists, Association of Obstetrician Anesthesiologists-Resuscitators. Single-child labor, delivery by caesarean section. Clinical guidelines. 2020. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://www.arfpoint.ru/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/kr-kesarevo-sechenie.pdf

- Mascarello К.С., Horta B.L., Silveira M.F. Maternal complications and cesarean section without indication: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Saude Publica. 2017; 51: 105. https://dx.doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2017051000389.

- Радзинский В.Е. Акушерская агрессия, v. 2.0. М.: Изд-во журнала Status Praesens; 2017. 872c. [Radzinsky V.E. Obstetric aggression, v. 2.0. Moscow: Status Praesens; 2017. 872p. (in Russian)].

- Савельева Г.М., Курцер М.А., Бреслав И.Ю., Коноплянников А.Г., Латышкевич О.А. Разрывы матки в современном акушерстве. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 9: 48-55. [Savelyeva G.M., Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Konoplyannikov A.G., Latyshkevich O.A. Uterine ruptures in modern obstetrics. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (9): 48-55. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.9.48-55.

- Sandall J., Tribe RM., Avery L., Mola G., Visser G.H., Homer C.S. et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018; 392(10155): 1349-57. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31930-5.

- Shi X.-M., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Wei Y.L., Chen L., Zhao Y.-Y. Effect of primary elective cesarean delivery on placenta accreta: a case-control study. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 2018; 131(6): 672-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.226902.

- Российское общество акушеров-гинекологов. Послеоперационный рубец на матке, требующий предоставления медицинской помощи матери во время беременности, родов и в послеродовом периоде. Клинические рекомендации. 2021. [Russian Society of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. A postoperative scar on the uterus that requires the provision of medical care to the mother during pregnancy, childbirth and in the postpartum period. Clinical guidelines. 2021. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://minzdrav.midural.ru/uploads/2021/07/Послеоперационный%20рубец%20на%20матке.pdf Accessed 12.01.2023.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 205: Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019; 133(2): e110-e127. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003078.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Birth after previous caesarean birth (Green-top Guideline No. 45). 2015. Available at: https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg_45.pdf Accessed 12.01.2023.

- Queensland Government. Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC). 2020. Available at: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/qcg Accessed 12.01.2023.

- Вученович Ю.Д., Новикова В.А., Радзинский В.Е. Альтернатива повторному кесареву сечению. Доктор.Ру. 2020; 19(6): 15-22. [Vuchenovich Yu.D., Novikova V.A., Radzinsky V.E. An Alternative to Repeat Cesarean Section. Doctor.Ru. 2020; 19(6): 15-22. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.31550/1727-2378-2020-19-6-15-22.

- Вученович Ю.Д., Новикова В.А., Костин И.Н., Радзинский В.Е. Риски несостоятельности рубца и попытки вагинальных родов после кесарева сечения. Акушерство и гинекология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2019; 7(3, Приложение): 93-100. [Vuchenovich Yu.D., Novikova V.A., Kostin I.N., Radzinsky V.E. Risk of uterine rupture during a trial of vaginal labor after cesarean. Obstetrics and Gynecology: News, Opinions, Training. 2019; 7(3, Suppl.): 93-100. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2303-9698-2019-13913.

- Пономарева О.А., Писарева Е.Е., Литвина Е.В., Дворецкая Ю.А., Ильина О.В. Хирургическая анатомия живота после кесарева сечения. Волгоградский научно-медицинский журнал. 2020; 2: 26-30. [Ponomareva O.A., Pisareva E.E., Litvina E.V., Dvoreckaya Y.A., Ilina O.V. Surgical anatomy of the abdomen after cesarean section. Volgograd Journal of Medical Research. 2020; (2): 26-30. (in Russian)].

- Айламазян Э.К., Павлова Н.Г., Поленов Н.И., Кузьминых Т.У., Шелаева Е.В. Морфофункциональная оценка нижнего сегмента матки в конце физиологической беременности и у беременных с рубцом. Журнал акушерства и женских болезней. 2006; 55(4): 11-8. [Ailamazyan E.K., Pavlova N.G., Polenov N.I., Kuzminih T.U., Shelaeva E.V. Morphofunctional evaluation of the lower uterine segment in physiological pregnancy and scarred uterus. Journal of Obstetrics and Women's Diseases. 2006; 55(4): 11-8. (in Russian)].

- Петрова Л.Е., Кузьминых Т.У., Коган И.Ю., Михальченко Е.В. Особенности клинического течения родов у женщин с рубцом на матке после кесарева сечения. Журнал акушерства и женских болезней. 2012; 61(6): 41-7. [Petrova L.E., Kuzminykh T.U., Kogan I.Yu., Mykhalchenko E.V. Characteristics of clinical progress of vaginal delivery after cesarean section. Journal of Obstetrics and Women's Diseases. 2012; 61(6): 41-7. (in Russian)].

Received 17.05.2023

Accepted 06.10.2023

About the Authors

Natalya B. Kuznetsova, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor, Professor at the Center for Simulation Training, Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakichevanskiy str., 29; Chief Physician, Clinic of Professor Bushtyreva, 344011, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Sobornyi str., 58/7,+7(928)770-97-62, lauranb@inbox.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0342-8745

Gulmira M. Ilуasova, post-graduate student, Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 344022, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Nakhichevansky str., 29; obstetrician-gynecologist, Clinic of Professor Bushtyreva, 344011, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Sobornyi str., 58/7, +7(989)613-04-03, gulmirka666@mail.ru

Irina O. Bushtyreva, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Director, Clinic of Professor Bushtyreva, 344011, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Sobornyi str., 58/7, +7(928)296-15-97, kio4@mail.ru

Vitaliy S. Gimbut, PhD, Doctor of Ultrasound Diagnostics, Clinic of Professor Bushtyreva, 344011, Russia, Rostov-on-Don, Sobornyi str., 58/7, +7(918)554-24-18,

vgimbut@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5608-5328

Natalia G. Pavlova, PhD, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductology, Pavlov First St. Petersburg State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 197022, Russia, St. Petersburg, Leo Tolstoy str., 6-8, ngp05@yandex.ru

Corresponding author: Gulmira M. Ilyasova, gulmirka666@mail.ru