Analysis of pain manifestations in extragenital endometriosis stage I–IV

Aim. To conduct a comparative analysis of pain manifestations in patients with extragenital endometriosis (EGE) stage I-IV with an emphasis on dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain.Timofeeva Yu.S., Volchek A.V., Kuleshov V.M., Marinkin I.O., Aidagulova S.V.

Material and methods. Nineteen two patients who underwent surgery for EGE were divided into three representative age groups based on the EGE stage, according to the Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis. Group 1 included 12 (13%) patients with stage I EGE, group 2 consisted of 60 (65%) patients with stage II EGE, and group 3 comprised 20 (22%) patients with stage III EGE. The control group included 90 patients of a similar age who had laparoscopy before undergoing assisted reproductive technologies (ART). For statistical analysis, nonparametric statistics were used.

Results. Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is one of the leading manifestations of pain in EGE II and III stages. The relationship between visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores and the location and extent of endometriotic lesions was episodic. A relationship was found between dyspareunia and endometriosis of pelvic peritoneum and uterosacral ligaments, and between CPP and focal lesions in the bladder peritoneum, ovaries, and retrocervical endometriosis.

Conclusion. Types of EGE-related pain and their combinations were not associated with specific stages of the disease. The presence and intensity of dyspareunia is a strong sign of the presence and extent of endometriosis of the pelvic peritoneum and uterosacral ligaments. This relationship is predictive and may help develop a diagnostic strategy and guide pre-surgical planning.

Keywords

The etiology and mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of EGE remain unclear and need further investigation. There are many questions to be answered to improve the quality of life of patients with endometriosis, including relieving endometriosis-related pain [1, 2] that occurs in almost half of patients with this disease [3, 4].

Clinical manifestations of EGE-related pain depend on the location of endometriotic lesions and their spread, dissemination of endometrial tissue, duration of the disease, and the individual patient characteristics. Endometriosis is associated with dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and cyclical or non- cyclical pelvic pain. Along with this, endometriosis can affect the bowel, urinary bladder, kidney, and pouch of Douglas, especially in deep endometriosis [5]. To date, it has not been possible to isolate endometriosis-specific pain. Patients with endometriosis may be asymptomatic at presentation or complain only about pelvic pain of varying intensity [1].

A combination of peripheral pain sensitizers, including various blood and peritoneal fluid chemokines and cytokines, may be involved in endometriosis-related pain. Besides, it is likely that central sensitization mechanisms are involved, such as structural changes in the brain, autonomic nervous system, and changes in the behavioral and central response to pathological stimulation [6–8].

When determining the stage of EGE and management strategy for treatment and psychological rehabilitation of patients with EGE, it is recommended to focus on dyspareunia-related complaints, and deep dyspareunia should be specifically differentiated from superficial dyspareunia [9].

In most studies, EGE-related pain was evaluated using a visual analog scale (VAS), which is the standard tool for the measurement of subjective perception of pain [10]. Endometriosis staging before surgery requires a differentiated approach to the diagnosis of pain [3]. Since chronic pelvic pain (CPP) can be a manifestation of pelvic inflammatory diseases and some somatic comorbidities, a differentiated assessment of endometriosis-associated pain is necessary. According to the experts of the Consensus [11], the assessment of EGE-associated pain should be carried out comprehensively even if patients have clear and cyclical symptoms.

The present study was aimed to conduct a comparative analysis of pain manifestations in patients with EGE stage I-IV with an emphasis on dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain..

Material and methods

This is a descriptive clinical study of 92 patients who underwent surgery from 2014 to 2016 at the Novosibirsk Regional Clinical Hospital and the Center for Family Health and Reproduction, which are affiliated to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Novosibirsk State Medical University. Criteria for inclusion in the study were as follows: indications for surgical treatment according to clinical recommendations [12], including infertility, endometriosis-associated pain, and the presence of endometriotic ovarian cysts measuring more than 3 cm in diameter, histologically verified EGE, and the patient informed consent. Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, malignancy, immunodeficiency, and decompensated extragenital diseases.

The patients were divided into three representative age groups based on EGE stage, according to the Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis [13]. This classification assigns point scores based on the total area and depth of endometriotic lesions. Group 1 included 12 (13%) patients with stage I EGE, group 2 consisted of 60 (65%) patients with stage II EGE, and group 3 comprised 20 (22%) patients with stage III EGE. The location of endometriotic lesions was determined by laparoscopy; surgical specimens were examined by light microscopy. The control group included 90 patients of a similar age who had laparoscopy before undergoing assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Taking into account the sample size, non-parametric statistical tests were used. The normality of the distribution was tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparing numerical data between two groups. The relationship between VAS scores and anatomic locations of endometriotic lesions was studied by univariate logistic regression analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between pain manifestations and anatomic locations of endometriotic lesions. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2019 and MedCalc Statistical Software version 18.9.1 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2018).

Results and discussion

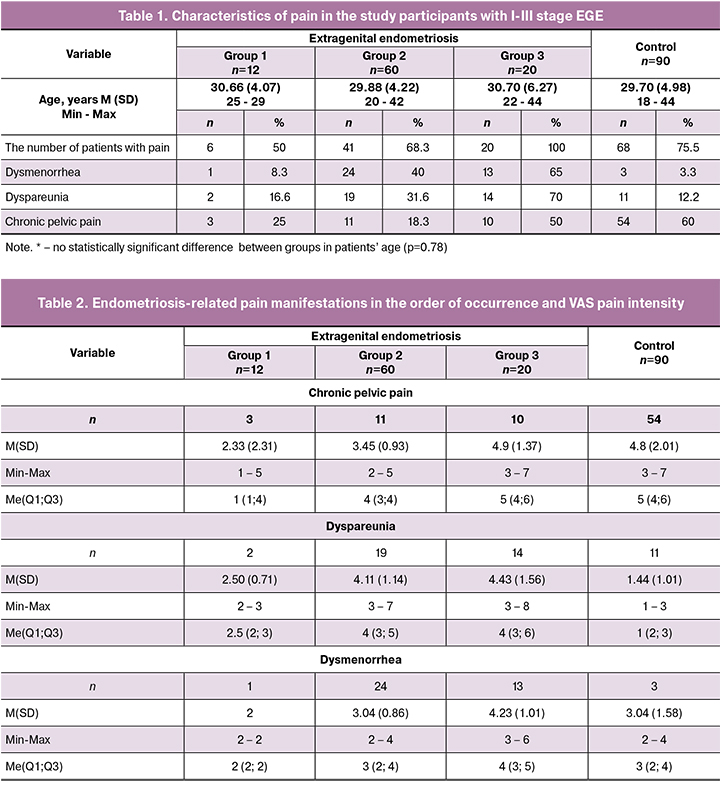

The age of patients with EGE assigned to the groups 1-3 varied from 29.88 to 30.70 [mean 30.16 (2.79)] years; in the control group mean age was 29.70 (2.49) years. There were no significant differences between study groups regarding women’s age (Table 1).

The most common EGE-related complaints were chronic lower abdominal and low back pain worsening during menstruation (Table 1). Among patients in the control group, CPP was mainly not related to the menstrual cycle and sexual intercourse. According to [2, 3], pain that is not related to the menstrual phase of the cycle is uncharacteristic of EGE, but it can occur in patients with severe abdominal and pelvic adhesions.

In patients with stage III EGE (group III), the incidence of CPP was 50% (Table 2), which may be associated with the disease progression and its transition to infiltrating endometriosis.

Dyspareunia is the second most common component of EGE-associated pain (Table 2). According to the classification of endometriosis-related dyspareunia without concomitant pathology [9], this is mainly stage I dyspareunia or primary deep dyspareunia. In group 2, a statistically significantly higher proportion of patients had EGE-related pain, and they had more than a twofold higher VAS pain intensity level compared with group 1.

Unlike deep dyspareunia, superficial dyspareunia (vestibulodynia) is extremely rare in endometriosis (in sporadic cases of vulvar endometriosis). However, patients with deep dyspareunia more often experience concomitant superficial dyspareunia due to central sensitization. According to [9], there is no consensus on whether there is a direct association between endometriosis stage and VAS dyspareunia intensity level. Some of our patients with stage I EGE reported dyspareunia VAS score 7, and patients with stage III of EGE could have score of only 5.

A statistically significant increase in the pain during menstruation was noted as the disease progressed. As is known, pain intensity can vary significantly in different menstrual cycles from the discomfort that does not require painkillers to the clinical signs of an acute abdomen, leading to hospitalization and emergency surgery [3].

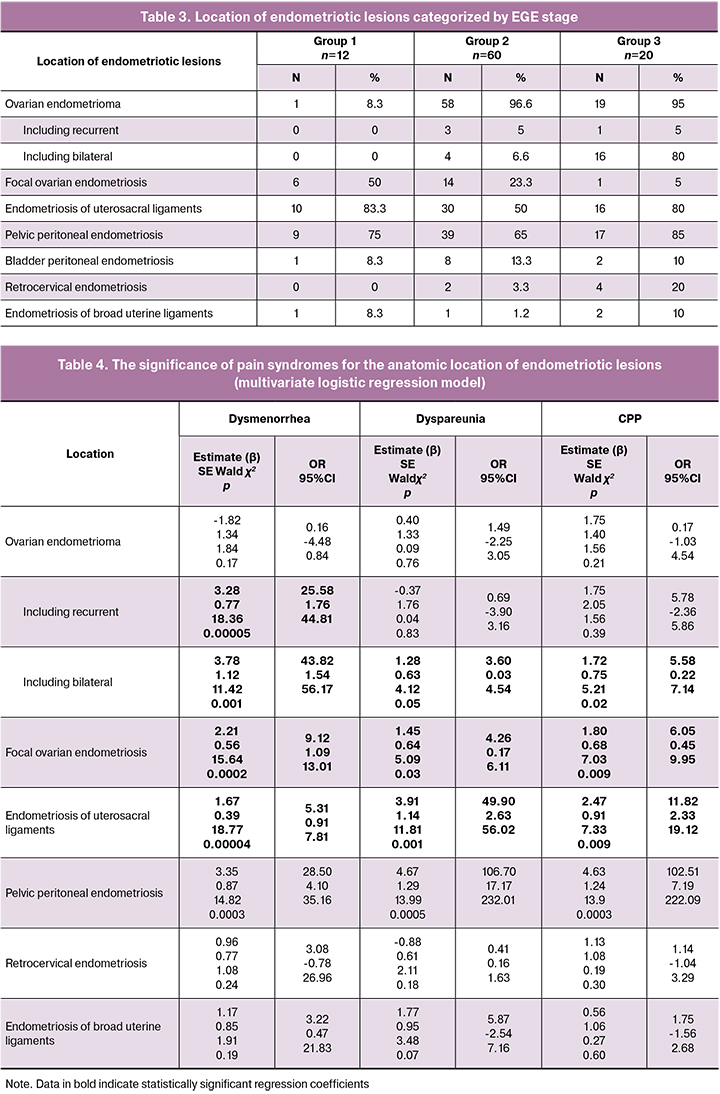

The presence and intensity of pain in patients with various endometriotic lesion sites are summarized in Table 3.

To identify anatomic locations of endometriotic lesions that are independently associated with a specific type of pain, we used a multivariate logistic regression model with three variables (Table 4).

We were interested in the feasibility of establishing the association between anatomical locations of endometriotic lesions and the presence or absence of a specific type of pain. The response variable was the presence or absence of endometriotic lesions in different locations. Data on the presence or absence of pain symptoms (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, CPP) were used as risk factors (predictor variables).

As seen from Table 4, the presence of dysmenorrhea is associated with 25.58 times higher odds of having recurrent ovarian endometrioma (95% CI 1.76–44.81), 43.82 times higher odds of having bilateral endometrioma(95% CI 1.54–56.17, 9.12 times higher odds of having focal ovarian endometriosis (95% CI 1.09–13.01), 5.31 times higher odds of having endometriosis of the broad uterine ligaments (95% CI 0.91–7.81), and 28.5 times higher odds of having pelvic peritoneal endometriosis (95% CI 4.10–35.16).

The presence of dyspareunia is associated with 3.60 times higher odds of having bilateral ovarian endometrioma (95% CI 0.03-4.54), 4.26 times higher odds of having focal ovarian endometriosis (95% CI 0.17-6.11), 49.90 times higher odds of having endometriosis of the broad uterine ligaments (95% CI 2.63–56.02), and 106.7 times higher odds of having pelvic peritoneal endometriosis (95% CI 17.17–232.01).

The presence of CPP is associated with 5.58 times higher odds of having bilateral ovarian endometrioma (95% CI 0.22–7.14), 6.05 times higher odds of having focal ovarian endometriosis (95% CI 0.45–9.95), 11.82 times higher odds of having endometriosis of the broad uterine ligaments (95% CI 2.33–19.12), and 102.51 times higher odds of having pelvic peritoneal endometriosis (95% CI 7.19–22.09).

Therefore, the presence of specific EGE-related pain is an important predictor of different endometriotic lesion sites.

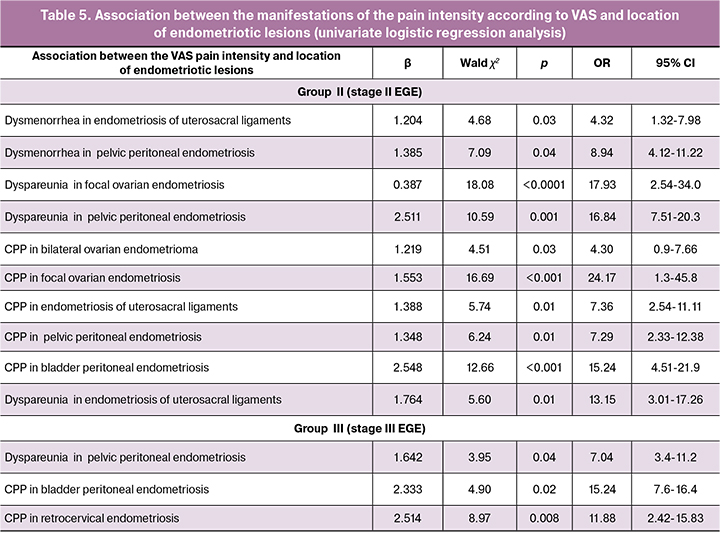

Then we studied the relationship between the VAS measure of pain and the location of endometriotic lesions using univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 5). Assessing the relationship between VAS scores and location of endometriosis sites is recommended for staging the disease and evaluating its severity [8].

In the logistic regression model for assessing the relationship between VAS scores for specific types of EGE-related pain, the VAS score was a predictor variable in terms of predicting higher odds of having endometriotic lesions in a particular anatomic location (binary categorical variable).

An increase in VAS pain score by 1 point increases the probability of endometriosis of the uterosacral ligaments by 4.32 times (95% CI 1.32–7.98).

Statistically significant correlations were found between the severity of pain and the topography of endometriotic lesions. In group 2, a correlation was found between the increase in the dyspareunia VAS score and the increased odds of pelvic peritoneal endometriosis. A 1-point increase in VAS score was associated with a 16.84 times higher odds of having pelvic peritoneal endometriosis (95% CI 7.51–20.83), 24.17 times higher odds of having CPP and focal ovarian endometriosis (95% CI 1.3–45.8), and 15.24 times higher odds of having CPP and bladder peritoneal endometriosis (95% CI 4.51–21.9).

In group 3, a relationship was found between the increase in the dyspareunia VAS score and the higher likelihood of having pelvic peritoneal endometriosis. A 1-point increase in VAS score was associated with a 7.04 times higher odds of having pelvic peritoneal endometriosis (95% CI 3.4–11.2); 15.24 times higher odds of having CPP and bladder peritoneal endometriosis (95% CI 7.6-16.4), and 11.78 times higher odds of having CPP with retrocervical endometriosis (95% CI 2, 42-15.83).

No relationship was observed between the VAS estimate of pain and the location of endometriotic lesions in group 1 patients. This observation may be attributed to the subjectivity of the method and to the fact that the predominant complaint of patients with stage I EGE was infertility, rather than pain.

In group 2, a statistically significant relationship was found between the site of the disease and VAS score of pain for a combination of dyspareunia with of the pelvic peritoneal endometriosis (p < 0.001), CPP and focal ovarian endometriosis (p < 0.001) and CPP with the bladder peritoneal endometriosis (p = 0.005).

In group 3, the relationship between the VAS pain scores and the location of endometriotic lesions was observed in a combination of dyspareunia and endometriosis of the uterosacral ligaments (p = 0.04), dyspareunia and pelvic peritoneal endometriosis (p = 0.02) and CPP with retrocervical endometriosis (p = 0.008).

EGE-associated pain was observed in 50%, 68.3%, and 100% of patients of groups 1, 2, and 3, which indicates an increased role of EGE-related pain in the progression of the disease. There was a statistically significant increase in the number of patients with dyspareunia (16.6–31.6–70%) and dysmenorrhea (8.3–40–65%). The analysis of CPP scores showed that there was no statistically significant difference between groups 1 and 2 (p = 0.48), which indicates the equal subjective significance of pelvic pain in stages I and II of EGE. No statistically significant differences in the presence of CPP was noted between group 3 and the control group of patients, which indicates the similarity of the clinical manifestation due to EGE-associated damage to the peritoneum and the subsequent development of adhesions.

Patients with monosymptomatic complaints predominated in group 1(41.6%), while in groups 2 and 3, significantly more patients had two types of EGE-related pain (8.3–36.6–55%). In groups 2 and 3, 15% of patients had all three types of EGE-related pain. There was no difference in combinations of pain types between the control group and group 1.

A statistically significant increase in VAS pain score was observed in the presence of CPP depending on EGE stage of [2.33 (1.44) → 3.45 (0.93) → 4.9 (1.37)], however, there was no difference between group 3 and control groups are absent, which also indicates the similarity of the clinical manifestations of peritoneal lesions and adhesions.

There were no statistically significant differences in dyspareunia VAS scores between groups 2 and 3.

Nevertheless, the analysis of endometriotic lesion locations and VAS estimates of dyspareunia showed the following pattern. There was a statistically significant increase in dysmenorrhea VAS scores depending on EGE stage [2 → 3.04 (0.85) → 4.23 (1.55)]. Comparisons for the control group could not be made due too few cases.

Pathomorphological findings showed that in all groups, the most common location of endometriotic lesions were the uterosacral ligaments (83.3 → 50 → 80%) and pelvic peritoneum (75 → 65 → 85%). In groups 2 and 3, the most common were ovarian endometriomas (96.6 and 95%), including recurrent endometriomas (80%), which is a classifying sign.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study confirmed that EGE-associated pain increases in parallel with an increase in the stage of the disease with the emergence of new symptoms and increasing VAS pain scores. Types of EGE-related pain and their combinations were not associated with specific stages of the disease.

The average quality of the regression models (42–61%) does not allow for the use to the full extent the analysis of the pain for localizing endometriotic lesion sites. In the created regression model, the relationship between VAS pain scores and endometriotic lesion sites was episodic. But our study showed the relationship between dyspareunia and endometriosis of pelvic peritoneum and uterosacral ligaments (p = 0.001) and between CPP and focal lesions in the bladder peritoneum (p < 0.001), ovaries (p < 0.001), and retrocervical endometriosis (p = 0.008).

CPP is one of the leading manifestations of pain in EGE II and III stages due to focal lesions of pelvic peritoneum and scarring and adhesion formation.

The presence and intensity of dyspareunia is a strong sign of the presence and extent of endometriosis of the pelvic peritoneum and uterosacral ligaments. This relationship is predictive and may help develop a diagnostic strategy and guide pre-surgical planning.

References

- Rogers P.A., Adamson G.D., Al-Jefout M., Becker C.M., D’Hooghe T.M., Dunselman G.A., Fazleabas A., Giudice L.C., Horne A.W., Hull M.L., Hummelshoj L., Missmer S.A., Montgomery G.W., Stratton P., Taylor R.N., Rombauts L., Saunders P.T., Vincent K., Zondervan K.T.; WES/WERF Consortium for Research Priorities in Endometriosis. Research Priorities for Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017; 24(2): 202-226. doi: 10.1177/1933719116654991

- Tai F.W., Chang C.Y., Chiang J.H., Lin W.C., Wan L. Association of pelvic inflammatory disease with risk of endometriosis: A nationwide cohort study involving 141,460 individuals. J Clin Med. 2018; 7(11). pii: E379. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7110379

- Ярмолинская М.И., Айламазян Э.К. Генитальный эндометриоз. Различные грани проблемы. СПб.: Эко-Вектор, 2017: 16-21. [Yarmolinskaya M.I., Ajlamazyan Eh.K. Genital’nyj ehndometrioz. Razlichnye grani problemy. SPb.: Ehko-Vektor, 2017:16-21. (In Russ.)].

- Shah R., Jagani R.P. Review of endometriosis diagnosis through advances in biomedical engineering. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2018; 46(3): 277-288.doi: 10.1615/CritRevBiomedEng.2018027414.

- Zondervan K.T., Becker C.M., Koga K., Missmer S.A., Taylor R.N., Viganò P. Endometriosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018; 4(1): 9. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0008-5.

- Brawn J., Morotti M., Zondervan K.T., Becker C.M., Vincent K. Central changes associated with chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update, 2014; 20: 737-47. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmu025

- Morotti M., Vincent K., Brawn J., Zondervan K.T., Becker C.M. Peripheral changes in endometriosis-associated pain. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014; 20 (5): 717-736. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu021

- Morotti M., Vincent K., Becker C.M. Mechanisms of pain in endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017; 209: 8-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.07.497

- Yong P.J., Williams C., Yosef A., Wong F., Bedaiwy M.A., Lisonkova S., Allaire C. Anatomic sites and associated clinical factors for deep dyspareunia. Sex Med. 2017; 5(3): e184-e195. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2017.07.001

- de Freitas Fonseca M., Aragao L.C., Sessa F.V., Dutra de Resende J.A. Jr, Crispi C.P. Interrelationships among endometriosis-related pain symptoms and their effects on health-related quality of life: a sectional observational study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018; 61(5): 605-614. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2018.61.5.605

- Johnson N.P., Hummelshoj L., Adamson G.D., Keckstein J., Taylor H.S., Abrao M.S., Bush D., Kiesel L., Tamimi R., Sharpe-Timms K.L., Rombauts L., Giudice L.C. for the World Endometriosis Society Sao Paulo Consortium. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017; 32(2): 315-324. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew293.

- Адамян Л.В., Куликов В.И., Андреева Е.Н. Эндометриозы: Руководство для врачей. М.: Медицина, 2006. 416 с. [Adamyan L.V., Kulakov V.I., Andreeva Ye.N. Endometriosis. A manual for the physician. 2nd revised and updated edition. Moscow; 2006. 416 p. (in Russian)].

- Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil. Steril. 1997; 67 (5): 817–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81391-x.

Received 09.01.2019

Accepted 22.02.2019

About the Authors

Yulia S. Timofeyeva, assistent of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of Novosibirsk State Medical University (NSMU), Phone: +79061947755,e-mail:dr.yustimofeeva@gmail.com

Alexandr V.Volchek, junior researcher of the laboratory of cellular biology and fundamental basis of reproduction of NSMU’s Central scientific laboratory. Phone:+79130031722, e-mail:alexander@volcheck.ru

Vitaliy M. Kuleshov, doctor of medical sciences, professor, professor of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of NSMU. Phone:+7(383)341-04-36,

kuleshov_vm@mail.ru

Igor’ O. Marinkin, doctor of medical sciences, professor, the head of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of NSMU and rector of NSMU. Phone: +7(383)222-32-04, e-mail:rector@ngmu.ru

Svetlana V. Aidagulova, doctor of biological sciences, professor, head of the laboratory of cellular biology and fundamental basis of reproduction of NSMU’s

Central scientific laboratory. Phone:+79139092251, e-mail: s.aydagulova@gmail.com ORCID 0000-0001-7124-1969

For citation: Timofeeva Yu.S., Volchek A.V., Kuleshov V.M., Marinkin I.O., Aidagulova S.V. Analysis of pain manifestations in extragenital endometriosis stage I-IV.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/ Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; 11: 129-35.(In Russian).

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.11.129-135