Development and validation of an artificial intelligence-based system for predicting preterm birth using clinical data

Boldina Yu.S., Ivshin A.A., Svetova K.S.

Background: Preterm birth is a leading cause of neonatal mortality and disability, resulting in serious socio-economic consequences. Due to the high frequency of this condition, which has persisted for decades, there is a need for more effective tools to predict it.

Objective: To develop and validate an artificial intelligence-based system for predicting preterm birth using the data from electronic health records (EHR).

Materials and methods: The study used a dataset of 10,000 anonymized EHRs and 54 clinical variables. The system included an NLP model (based on RuBERT) for extracting the signs of preterm birth from the health records in the Russian language and a predictive model based on machine learning for assessing the risk of preterm birth.

Results: The CatBoost classifier demonstrated optimal prediction performance with the following parameters: accuracy = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.799 –0.821), recall = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.857–0.883), precision = 0.76 (95% CI: 0.748–0.772), F1-score = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.805–0.815), and AUC-ROC = 0.82 (95% CI: 0.809–0.831).

Conclusion: The developed system for predicting preterm birth showed metrics comparable to foreign analogues and stability during validation. This confirms its potential use for implementing in real obstetric practice.

Authors’ contributions: Boldina Yu.S. – developing the concept and design of the study, preparing and editing the draft manuscript; Ivshin A.A. – developing the concept and design of the study, expert analysis of the results, editing the manuscript; Svetova K.S. – collecting the data, analysis and interpretation of the results.

Conflicts of interest: Authors declare lack of the possible conflicts of interest.

Funding: The study was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation, project No. 24-25-00429,

https://rscf.ru/project/24-25-00429/

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Boldina Yu.S., Ivshin A.A., Svetova K.S. Development and validation of an

artificial intelligence-based system for predicting preterm birth using clinical data.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (12): 74-87 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.213

Keywords

In recent decades, there have been significant advances in the fields of obstetrics and neonatal care, but preterm birth continues to be a global unresolved issue. The frequency of preterm birth ranges from 5 to 18% in the world; in Russia it reaches 4-6%, and in specialized perinatal centers this figure exceeds 9% [1]. Preterm birth remains the leading cause of neonatal mortality and the second most important cause of death in children under 5 years of age [2].

The consequences of preterm birth are catastrophic: from high mortality (98%), cerebral palsy and retinopathy in early gestation (22–28 weeks) to chronic diseases in late gestation (34–37 weeks) [3, 4]. Preterm birth causes enormous demographic and socio-economic damage due to the cost of intensive care and rehabilitation.

Up to 70% of preterm birth occur spontaneously; in many cases, the causes remain unclear, despite studies of various predictors, including infectious factors [5], cervical incompetence and socio-demographic determinants [6–8]. In addition, the role of certain markers in the development of premature rupture of membranes and preterm birth, such as placental alpha microglobulin-1 (PAMG-1), has been identified [9, 10].

All measures taken in the event of threatened preterm labor aim to delay labor for a short period of time, but they do not guarantee a prolonged pregnancy. The effectiveness of preterm birth prevention remains controversial, while a number of studies emphasize the usefulness of micronized progesterone, cervical pessary and cervical cerclage in patients at risk of preterm birth [1, 14].

The multifactorial nature of preterm birth necessitates the introduction of innovative technologies such as machine learning (ML) for complex data analysis and individual risk assessment [5].

ML has several important advantages, including the ability to analyze large amounts of medical data, identify complex relationships between predictors, and integrate heterogeneous parameters, from medical history data to laboratory tests and graphical medical information.

In recent years, ML algorithms have shown high effectiveness in predicting obstetric complications such as fetal growth retardation [15], postpartum hemorrhage [16], and preeclampsia [17]. Special attention needs to be paid to the innovations developed by the Russian scientists in the field of obstetrics and gynecology using ML-technologies. In the study, Andreichenko A.E. et al. (2023) designed and validated models for predicting preeclampsia and its early forms based on the data obtained in the first trimester of pregnancy [18].

The results of foreign researchers demonstrate the potential in the development of multiparametric models for assessing the risk of preterm birth using ML algorithms. For example, in a recent study by Chen Y. et al. (2024), the XGBoost algorithm showed high accuracy in predicting spontaneous preterm birth (AUC 0.89; 95% CI: 0.88–0.90) and identified 10 key predictors of preterm birth including biochemical markers [19]. Zhang Y. et al. (2023) confirmed the prospects of using the AdaBoost algorithm (95.4% accuracy, AUC 0.93) that identified the main risk factors of preterm birth, namely multifetal pregnancy, premature rupture of membranes, placenta previa, and antepartum hemorrhage [20]. Random Forest in a study conducted by Sun Q. et al. (2022), showed AUC 0.885 (95% CI: 0.873–0.897), using clinical and biochemical parameters and data of 9550 pregnant women to predict preterm birth [21].

The wide range of quality of existing prognostic models and their limited use in clinical practice highlight the need for continued search for reliable, practice-oriented forecasting tools of preterm birth.

The aim of the study is to develop and validate an artificial intelligence-based system for predicting preterm birth using the data from electronic health records (EHR).

Materials and methods

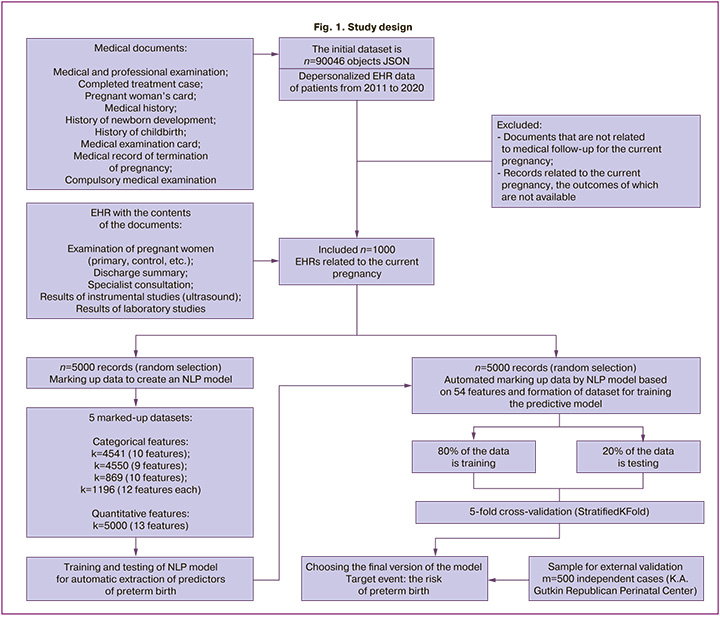

The data source. A retrospective analysis of 10,000 unstructured EHR obtained during monitoring of pregnant women was performed. The data was previously anonymized by the operator in accordance with legal and ethical requirements. This eliminated the need for obtaining informed consent from the patients. In order to extract clinically significant parameters of preterm birth, the processing of unstructured EHR data was carried out using the natural language processing (NLP) model developed for this study. The details of the NLP model development process are presented in the corresponding section.

Participants. The initial dataset consisted of 90,046 depersonalized medical records in JSON format, collected between March 2011 and July 2020. The records with clinical data obtained during the current pregnancy of women were selected for the study. The unit of analysis was a medical record reflecting a documented case of providing medical care to a pregnant patient, indicating the gestational age and current clinical and laboratory parameters at the time of the visit. The data was selected according to the following inclusion criteria: 1) the confirmed fact of pregnancy on the basis of the ICD-10 codes; 2) information about the outcome of pregnancy (according to the ICD-10 codes in the EHR).

As a result of the selection, a dataset was formed which included 10,000 EHR, subsequently divided into two equal parts for training the NLP model and automatic processing by the NLP model in order to create a training sample for the predictive model of the preterm birth.

The validation sample included 500 unique cases of pregnancy that resulted in preterm birth, based on a survey of medical records of patients at the K.A. Gutkin Republican Perinatal Center from 2016 to 2022. A schematic representation of the research design is shown in Figure 1.

Outcomes. The target event group included all medical records of patients who were diagnosed with either threatened preterm labor during the current pregnancy, or preterm birth according to the relevant ICD-10 codes (O47.0, 47.9, O60). The remaining records without the corresponding ICD-10 codes formed the control group.

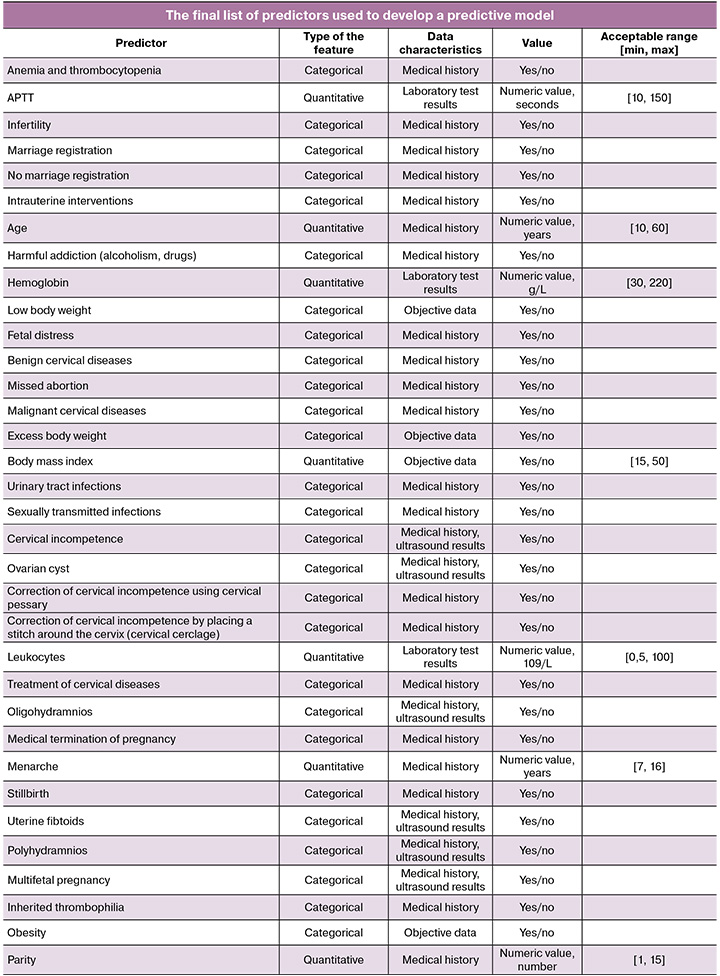

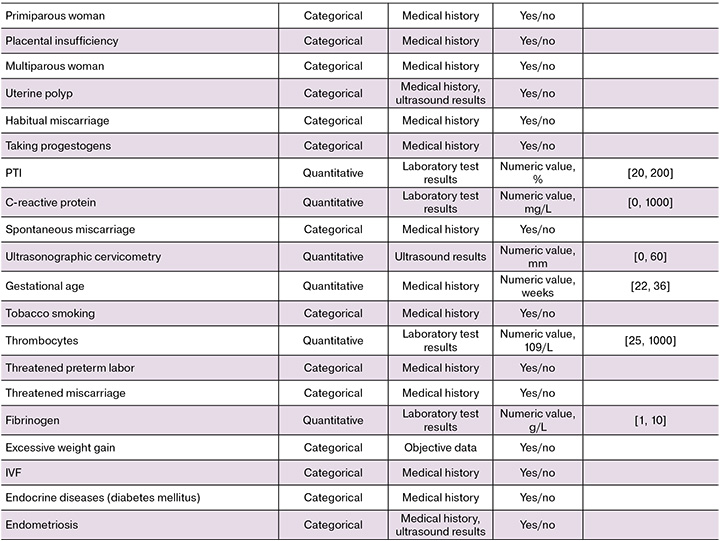

Predictors. Fifty-four potential predictors of preterm birth were analyzed including medical history, objective data, and clinical and laboratory parameters. Both categorical variables (according to the “yes/no” principle) and quantitative predictors were evaluated. Anamnestic factors included concomitant or previous illnesses, the presence of bad habits, marital status, functioning characteristics of the reproductive system (for example, infertility, parity, gynecological diseases).

Objective data included parameters such as body mass index and weight gain during pregnancy. Clinical predictors characterizing the course of a current pregnancy included multifetal pregnancy, cervical incompetence, threatened miscarriage, correction, signs of distress and fetal growth retardation, pathophysiology of amniotic fluid, gestational age at preterm birth. The length of the closed part of the cervix according to transvaginal ultrasonographic cervicometry was used as an instrumental predictor. Laboratory parameters included the level of hemoglobin, platelets, and leukocytes, the value of C-reactive protein (a non-specific marker of inflammation), and coagulogram parameters. The full list and characteristics of the predictors are presented in the Appendix.

Marking up data for building the NLP model. Categorical features were marked up using dictionaries of terms, synonyms, and abbreviations taking into account the context and negatives. For example, for the “smoking” parameter, the options included “tobacco smoking”, “smokes”, and “nicotine addiction”. Quantitative indicators were extracted using special patterns that capture the name of the parameter and its numerical value, for example, “hemoglobin”, value “120”, units “g/L”. The ICD-10 codes were searched according to the standard nomenclature, taking into account various formats of recording, for example, diagnosis O34.3 referring to cervical incompetence could be recorded as O34.3 or O343. As a result of the processing, four separate sets of categorical data were generated with a volume of 4,541, 4,550, 869 and 1,196 records, respectively, and 5,000 records for quantitative features.

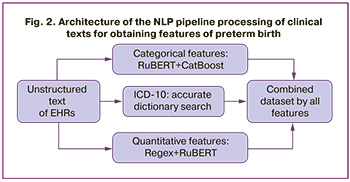

NLP model architecture. The pre-trained RuBERT (rubert-base-cased-conversational) model which was optimized for the Russian-language medical texts was used as the basic architecture. The text was processed and converted into a vector representation. The classification of qualitative features was done using the CatBoost algorithm. Quantitative predictors were processed using a hybrid method: a pattern search using regular expressions for numerical values (for example, “fibrinogen – 3.5 g/L”) was supplemented by RuBERT analysis for implicit cases (for example, “fibrinogen increased (3.5)”). All data was checked for compliance with the reference values and the clinical context. The ICD-10 codes were searched accurately with a standard dictionary. The principle of text processing using the NLP model is schematically shown in Figure 2.

The trained NLP model was used to automatically mark up 5,000 EHR, creating a dataset with a distribution of categorical features, numerical values, and ICD-10 codes to train a model for predicting preterm birth.

Data preprocessing for predictive model training. Data preprocessing was implemented using modern Python libraries (pandas, scipy.stats, sklearn.preprocessing) and included correlation analysis by constructing a Pearson thermal matrix, correcting outliers and filling in missing values, Z-normalization of numerical data, and balancing classes in the training dataset. Missing numerical indicators (such as laboratory data) were filled in with median values, missing categorical features were automatically replaced with zero values, which were interpreted as the absence of any abnormalities. The outliers were detected using an interquartile range (IQR) with boundaries [Q1-1.5·IQR; Q3+1.5·IQR] with additional physiologically justified restrictions that exclude impossible values (for example, negative concentrations). All detected abnormal values were replaced by the maximum values of the permissible range.

The class imbalance was eliminated by the SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) method, which created synthetic examples based on available data, as a result of which the class ratio reached approximately 50/50.

Statistical analysis

The analytical part of the study was performed using Python software (version 3.9). The normality of the distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for quantitative indicators and a frequency analysis. For qualitative indicators, the χ2 test was used to check for uniformity. To compare the indicators between groups with and without a target event, the following methods were used: 1) parametric Student’s t-test (with a normal distribution of quantitative variables); 2) the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test (in case of deviations from the normal distribution); 3) the χ2 test (for qualitative variables). The significance level of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

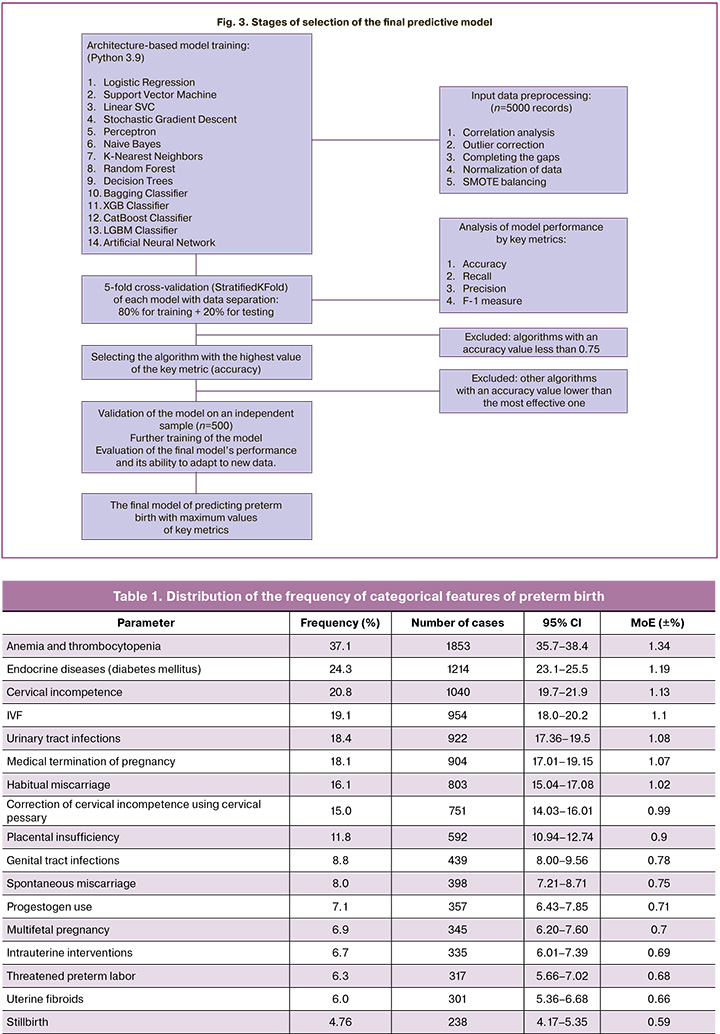

During the development of the predictive model, the effectiveness of 14 ML algorithms was comprehensively assessed, including a comparison of traditional statistical methods (logistic regression) with modern ML algorithms (ensemble methods and neural networks). The following classifiers were included in the study: Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Linear Support Vector classifier (Linear SVC), Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Perceptron, Naive Bayes (NB), k-Nearest Neighbors algorithm (k-NN). The following ensemble methods were used: Random Forest, Decision Trees, bagging classifier, gradient boosting methods (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN).

All models were evaluated using 5-fold stratified cross-validation on balanced data (StratifiedKFold). The following parameters were used for a comprehensive assessment: AUC-ROC (ability to differentiate classes), accuracy (classification accuracy), recall (sensitivity), precision (accuracy of a positive forecast) and F1-score (balanced measure) [22, 23]. Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated using the t-distribution, which ensured the statistical reliability of the results. The classification threshold is set at 0.5, in line with common practice for binary medical models [24]. The predictor ranking is done using built-in gradient boosting techniques.

The final validation was conducted on an independent sample of 500 clinical observations from the database of the Republican Perinatal Center with an analysis of the performance characteristics, error matrix, and key metrics. The following criteria were used to select the optimal model: maximum AUC-ROC, stability of metrics during cross-validation, and clinical interpretability with a standard threshold of 0.5. The selection scheme of the final model is shown in Figure 3.

Results

Descriptive statistics

At the sampling stage, two classes of observations were identified: class 1 with a target event (preterm birth) – 317 cases (6.3% of the total sample) and class 0 without a target event – 4683 observations (93.7%). This distribution reflects the class imbalance characteristic of this clinical situation. The imbalance corresponds to the actual epidemiological picture of the prevalence of preterm birth and at the same time ensures a sufficient number of positive cases for statistical analysis.

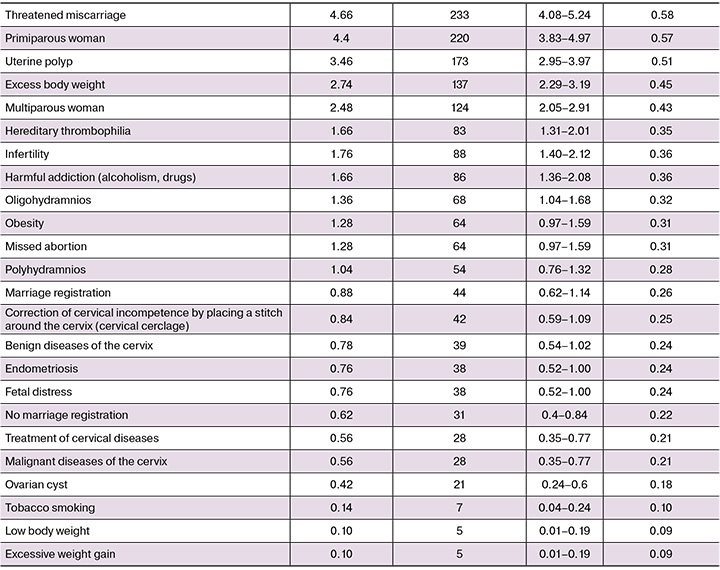

Frequency analysis of categorical features revealed significant variability, namely from 0.1 to 37.1%. The most common predictors (incidence >15%) were anemia and thrombocytopenia, endocrine diseases, cervical incompetence and correction with cervical pessary, habitual miscarriage, in vitro fertilization (IVF) and urinary tract infections. The frequency of such parameters as placental insufficiency, genital tract infections, a history of spontaneous miscarriage, taking progestogens, and multifetal pregnancy was observed in 5–15% of cases. Conditions with a low incidence (1-5%) included 17 variables, such as stillbirth (4.8%), threatened miscarriage (4.7%), and first birth (4.4%). Smoking, body weight deficiency, and excessive weight gain were considered rare conditions (<1%). A detailed analysis of the frequency distribution of the categorical features under study is presented in Table 1.

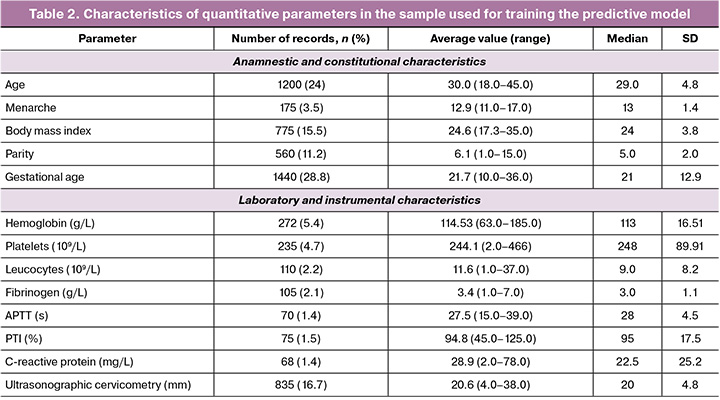

The analysis of quantitative indicators revealed that the average gestational age at the time of the analysis was 21 weeks. Age (24% of the records), parity (11.2%), and gestational age (28.8%) were the most fully documented. Ultrasonographic cervicometry (16.7%), hemoglobin level (5.4%), and platelet count (4.7%) were the most common laboratory and instrumental parameters. A detailed description of the quantitative characteristics is presented in Table 2.

The analysis revealed statistically significant differences (p<0.05) in the frequency of predictors between the target and control groups. The greatest contributors to the risk of preterm birth were placental insufficiency (it was 2.5 times more common in preterm birth, 26.5% versus 10.8%), use of IVF (25.9% versus 18.6%), and cervical incompetence (25.6% versus 20.5%). Other significant factors included polyhydramnios (3.2% in preterm birth versus 0.9%), benign cervical diseases (2.5% versus 0.7%), primiparous women (8.2% versus 4.1%).

To evaluate the predictive accuracy of the model using independent data, a validation sample was formed, including 500 cases from the K.A. Gutkin Republican Perinatal Center. The class ratio (6.3% of cases of preterm birth versus 93.7% of normal birth) corresponded to the structure of the training sample and provided clinical representativeness of clinical and demographic parameters. The model validation sample showed a more complete coverage of key parameters, such as age (100%), body mass index (98%), and gestational age (91.2%), compared to the training sample (24%, 15.5%, and 28.8%, respectively). Additionally, there was an increased frequency of critical predictors, such as placental insufficiency (24.2% vs. 11.8%) and polyhydramnios (12.0% versus 1.04%). This data structure made it possible to carry out a more thorough evaluation of the model under conditions as close to real clinical practice as possible, which is essential to confirm its predictive accuracy.

The development of the predictive model

To develop a predictive model, 14 ML algorithms were tested (they were described in detail in the Statistical methods section). The model analyzed 54 clinical and anamnestic parameters automatically extracted from EHR using the developed NLP system. A complete list of potential predictors of preterm birth is provided in the Appendix to the study.

The initial balanced data was divided into training (80%) and test (20%) samples. The optimal parameters were selected for each type of model. The modeling was performed taking into account the specific characteristics of the medical data, including the imbalanced class distribution and the clinical relevance of the predictors. To minimize the impact of the initial class imbalance, SMOTE technology was used to ensure a balanced class ratio. However, in order to avoid overfitting on synthetic data, an integrated validation approach was used. This approach included the following: 1) 5-fold stratified cross-validation; 2) testing on a sample with a natural distribution of classes; 3) evaluation using metrics resistant to imbalance (F1-score and AUC-ROC). This multilevel approach allowed us to create a model that retains a high predictive ability based on both balanced and initial unbalanced data, which is especially important for clinical practice, where the frequency of preterm birth is traditionally low.

Optimization of the algorithm included a comprehensive assessment of the proportion of correct classifications (accuracy) with 5-fold cross-validation and calculation of 95% confidence intervals. The most effective algorithm was additionally tested on an independent sample using a standard validation protocol.

Model performance

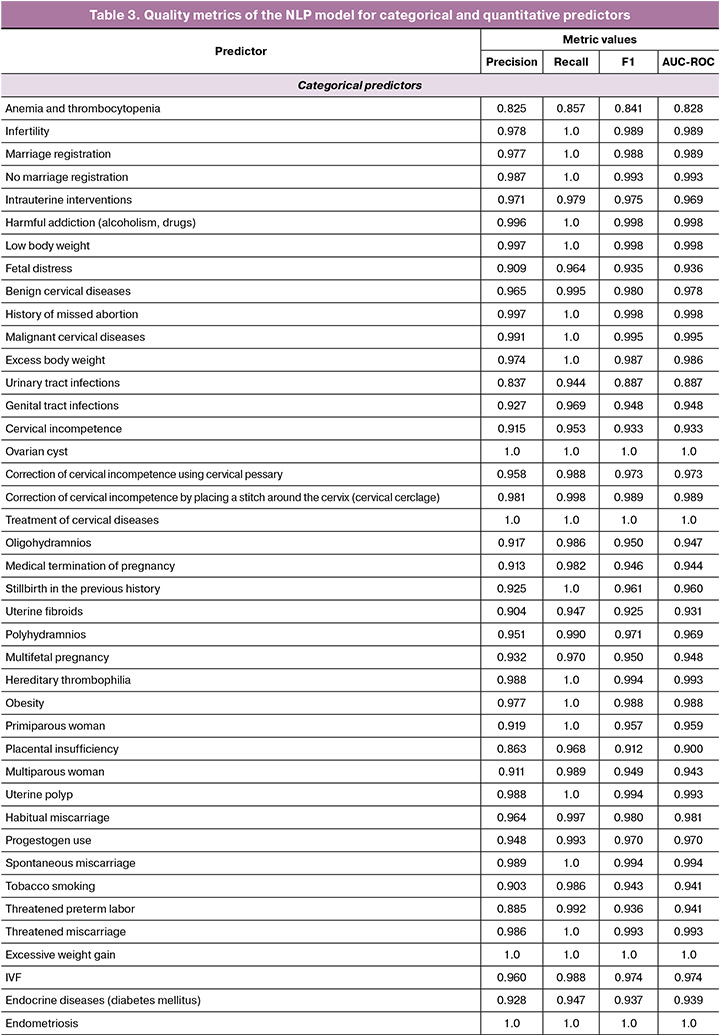

The NLP model demonstrated the following median values: F-measure 0.976, completeness 0.998, and AUC-ROC 0.974. The full list of metrics obtained for categorical and quantitative predictors is shown in Table 3. The high performance of the NLP model ensured the creation of a high-quality dataset for training a predictive model.

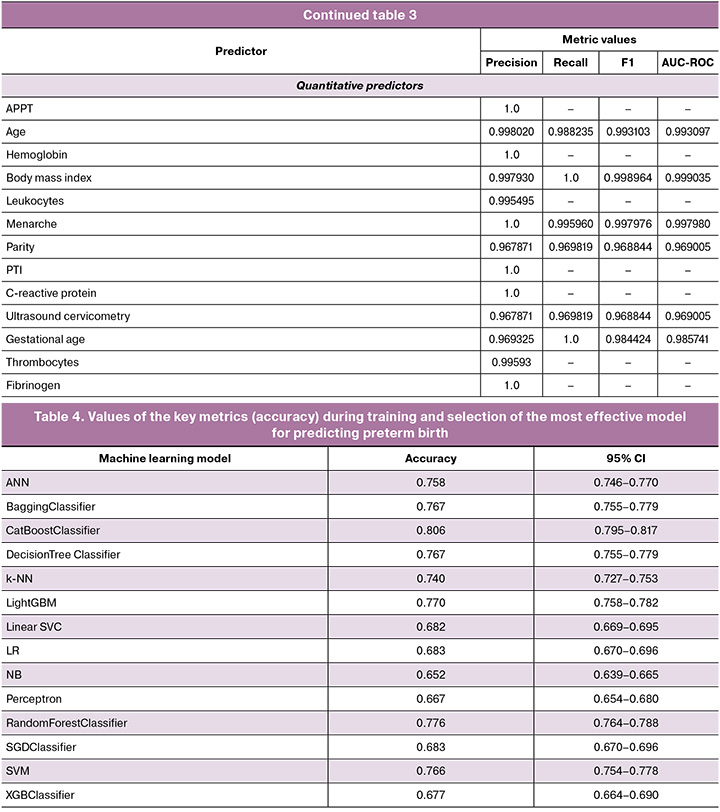

The indicators of the key metric of effectiveness (accuracy) for ML algorithms that solve the problem of predicting preterm birth are presented in Table 4. The CatBoost Classifier algorithm which was based on the gradient boosting method demonstrated the greatest effectiveness. It had the following indicators on internal validation: accuracy 0.8064 (95% CI: 0.784–0.816), sensitivity 0.76 (95% CI: 0.748–0.772), F1-measure 0.79 (95% CI: 0.782–0.798) and AUC-ROC 0.79 (95% CI: 0.774–0.806). When validated on an independent sample, the model confirmed high discriminative ability and resistance to new data, increasing AUC-ROC to 0.82 (95% CI: 0.809–0.831), sensitivity to 0.87 (95% CI: 0.857–0.883), accuracy to 0.81 (95% CI: 0.799–0.821) and F1-score up to 0.81 (95% CI: 0.805–0.815).

The system developed to predict preterm birth is able to automatically analyze risk factors of preterm birth on the basis of EHR, revealing the relationship between clinical, anamnestic and socio-demographic data. The model demonstrates high accuracy in predicting the risk of preterm birth in the early stages, which makes it possible to optimize pregnancy management tactics.

Discussion

Preterm birth is severe obstetric complication with a high risk to the life and health of mother and child. Despite the existing preventive measures, the frequency of preterm birth remains consistently high, requiring the search for new methods of prediction. The complex multicomponent pathogenesis of preterm birth, combining infectious, endocrine, and coagulation disorders, has a high degree of variability, which limits the use of standard preventive approaches and reduces their clinical effectiveness [25, 26]. Therefore, artificial intelligence techniques are becoming increasingly important, as they provide a means of analyzing complex interactions between various factors and an individualized risk assessment for preterm birth. Their implementation in clinical practice can help reduce the frequency of preterm birth and improve perinatal outcomes by improving the quality of prediction.

In the course of the study, two interrelated artificial intelligence models were developed: an NLP model for extracting preterm birth predictors from EHR and a predictive model that showed high accuracy in predicting preterm birth (AUC 0.82, Recall 0.87). The system’s performance is comparable to the results of foreign researchers [19-21]. However, unlike studies using a narrow set of biomarkers (for example, alkaline phosphatase, alpha-fetoprotein or placental growth factors), our model includes a wide range of available predictors, which allows us to take into account the complex influence of socio-demographic, obstetric and somatic factors on preterm birth.

In addition, the developed system is adapted to the specifics of the Russian-language electronic medical documentation, including the processing of unstructured text data using NLP algorithms, while foreign analogues work with the English-language standardized datasets. The use of special NLP algorithms for data analysis ensured the formation of a high-quality training dataset. External validation has confirmed high predictive accuracy and stability when working with new data, which indicates that the system is ready for clinical implementation [20]. The obtained characteristics meet the strict requirements of modern evidence-based medicine for predictive models and allow us to consider this system as a promising tool for supporting medical decisions. The possibilities for developing a system of predicting preterm birth include expanding the sample due to multicenter data and the inclusion of additional laboratory and genetic markers of preterm birth.

Artificial intelligence is a promising tool for predicting preterm birth and it has a number of key advantages. The main advantage of the method lies in the possibility of analyzing clinical data already collected from EHR during the standard clinical follow-up without the need for additional expensive studies. ML algorithms effectively work with standard clinical and anamnestic indicators, the results of laboratory and instrumental studies, revealing complex relationships between numerous risk factors. Although the development of accurate prognostic models requires careful processing of large amounts of high-quality data, the use of ML methods opens up new prospects for the development of predictive medicine in obstetric practice, allowing timely identification of patients at high risk of complications.

Conclusion

The developed system has demonstrated high effectiveness in predicting preterm birth due to the creation of a specialized NLP model for processing the Russian-language medical texts and creating a high-quality training dataset. The stability of the model based on CatBoost Classifier has been confirmed by testing, which allows it to be recommended for use in routine obstetric practice. This study lays the groundwork for developing a comprehensive solution using artificial intelligence technologies to analyze real clinical data, with the prospect of improving the quality of the tool. This could be achieved by expanding the range of predictors of preterm birth, validating data from different regions, and optimizing the preprocessing of data in future studies.

Appendix

References

- Ившин А.А., Погодин О.О., Шакурова Е.Ю., Льдинина Т.Ю., Никитин В.С. Лапароскопический трансабдоминальный серкляж для лечения истмико-цервикальной недостаточности при беременности: клинический случай и обзор литературы. Акушерство, гинекология и репродукция. 2025; 19(1): 116-26. [Ivshin A.A., Pogodin O.O., Shakurova E.Yu., Ldinina T.Yu., Nikitin V.S. Experience of laparoscopic transabdominal cerclage for the correction of cervical insufficiency during pregnancy: a clinical case and literature review. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2025; 19(1): 116-26 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2025.578

- Серов В.Н., Сухорукова О.И. Эффективность профилактики преждевременных родов. Акушерство и гинекология. 2013; 3: 48-53. [Serov V.N., Sukhorukova O.I. The effectiveness of preterm birth prevention. Obsterics and Gynecology. 2013; (3): 48-53 (in Russian)].

- Risnes K., Bilsteen J.F., Brown P., Pulakka A., Andersen A.N., Opdahl S. et al. Mortality among young adults born preterm and early term in 4 Nordic Nations. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021; 4(1): e2032779. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32779

- Jeon G.W., Lee J.H., Oh M., Chang Y.S. Serial long-term growth and neurodevelopment of very-low-birth-weight infants: 2022 update on the Korean neonatal network. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2022; 37(34): e263. https://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e263

- Горина К.А., Ходжаева З.С., Белоусов Д.М., Баранов И.И., Гохберг Я.А., Пащенко А.А. Преждевременные роды: прошлые ограничения и новые возможности. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 1: 12-9. [Gorina K.A., Khodzhaeva Z.S., Belousov D.M., Baranov I.I., Gokhberg Ya.A., Pashchenko A.A. Premature birth: past restrictions and new opportunities. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (1): 12-9 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.1.12-119

- Назарова А.О., Малышкина А.И., Назаров С.Б. Факторы риска спонтанных преждевременных родов: результаты клинико-эпидемиологического исследования. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 9: 82-6. [Nazarova A.O., Malyshkina A.I., Nazarov S.B. Risk factors for spontaneous preterm birth: results of a clinical-epidemiological study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; 9: 82-6 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.9.82-86

- Белоусова В.С., Стрижаков А.Н., Свитич О.А., Тимохина Е.В., Кукина П.И., Богомазова И.М., Пицхелаури Е.Г. Преждевременные роды: причины, патогенез, тактика. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 2: 82-7. [BelousovaV.S., Strizhakov A.N., Svitich O.A., Timokhina N.V., Kukina P.I., Bogomazova I.M., Pitskhelauri N.G. Preterm birth: causes, pathogenesis, and management. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (2): 82-7 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.2.82-87

- Thain S., Yeo G.S.H., Kwek K., Chern B., Tan K.H. Spontaneous preterm birth and cervical length in a pregnant Asian population. PLoS One. 2020; 15(4): e0230125. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230125

- Друккер Н.А., Дурницына О.А., Никашина А.А., Селютина С.Н. Диагностическая значимость α-1-микроглобулина в развитии преждевременных родов. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 1: 81-5. [Drukker N.A., Durnitsyna O.A., Nikashina A.A., Selyutina S.N. The diagnostic value of α-1-microglobulin in the development of preterm labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; (1): 81-5 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.1.81-85

- Баев О.Р., Дикке Г.Б. Диагностика преждевременного разрыва плодных оболочек на основании биохимических тестов. Акушерство и гинекология. 2018; 9: 132-6. [Baev O.R., Dikke G.B. Diagnosis of premature rupture of the membranes based on biochemical tests. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; (9): 132-6 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2018.9.132-136

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Преждевременные роды. М.; 2020: 66 c. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Premature birth. Moscow; 2020: 66 p. (in Russian)].

- Манухин И.Б., Фириченко С.В., Микаилова Л.У., Телекаева Р.Б., Мынбаев О.А. Прогнозирование и профилактика преждевременных родов - современное состояние проблемы. Российский вестник акушера-гинеколога. 2016; 3: 9-15. [Manukhin I.B., Firichenko S.V., Mikailova L.U., Telekaeva R.B., Mynbaev O.A. Prediction and prevention of preterm birth: state-of-the-art. Russian Bulletin of Obstetrician-Gynecologist. 2016; 3: 9-15 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/rosakush20161639-15

- Ходжаева З.С., Дембовская С.В., Доброхотова Ю.Э., Сичинава Л.Г., Юзько А.М., Мальцева Л.И., Серова О.Ф., Макаров И.О., Ахмадеева Э.Н., Башмакова Н.В., Шмаков Р.Г., Клименченко Н.И., Муминова К.Т., Талибов О.Б., Сухих Г.Т. Медикаментозная профилактика преждевременных родов (результаты международного многоцентрового открытого исследования МИСТЕРИ). Акушерство и гинекология. 2016; 8: 37-43. [Khodzhaeva Z.S., Dembovskaya S.V., Dobrokhotova Yu.E., Sichinava L.G., Yuzko A.M., Maltseva L.I., Serova O.F., Makarov I.O., Akhmadeeva E.N., Bashmakova N.V., Shmakov R.G., Klimenchenko N.I., Muminova K.T., Talibov O.B., Sukhikh G.T.. Drug therapy for preterm birth: Results of the international multicenter open-label Mystery study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016; (8): 37-43 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2016.8.37-43

- Баринов С.В., Артымук Н.В., Новикова О.Н., Шамина И.В., Тирская Ю.И., Белинина А.А., Лазарева О.В., Кадцына Т.В., Фрикель Е.А., Атаманенко О.Ю., Островская О.В., Степанов С.С., Беглов Д.Е. Опыт ведения беременных группы высокого риска по преждевременым родам с применением акушерского куполообразного пессария и серкляжа. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 1: 140-8. [Barinov S.V., Artymuk N.V., Novikova O.N., Shamina I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Belinina A.A., Lazareva O.V., Kadtsyna T.V., Frikel E.A., Atamanenko O.Yu., Ostrovskaya O.V., Stepanov S.S., Beglov D.E. Experience in managing pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth, by using a dome-shaped obstetric pessary and cerclage. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; (1): 140-8 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.1.140-148

- Crockart I.C., Brink L.T., du Plessis C., Odendaal H.J. Classification of intrauterine growth restriction at 34-38 weeks gestation with machine learning models. Inform. Med. Unlocked. 2021; 23: 100533. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2021.100533

- Liu J., Wang C., Yan R., Lu Y., Bai J., Wang H. et al. Machine learning-based prediction of postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery: combining bleeding high risk factors and uterine contraction curve. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022; 306(4): 1015-25. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-06377-0

- Melinte-Popescu A.S., Vasilache I.A., Socolov D., Melinte-Popescu M. Predictive performance of machine learning-based methods for the prediction of preeclampsia-a prospective study. J. Clin. Med. 2023; 12(2): 418. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020418

- Андрейченко А.Е., Лучинин А.С., Ившин А.А., Ермак А.Д., Новицкий Р.Э., Гусев А.В. Разработка и валидация моделей прогнозирования общего риска преэклампсии и риска ранней преэклампсии с использованием алгоритмов машинного обучения в первом триместре беременности. Акушерство и гинекология. 2023; 10: 94-107. [Andreychenko A.E., Luchinin A.S., Ivshin A.A., Ermak A.D., Novitskiy R.E., Gusev A.V. Development and validation of models to predict total and early-onset preeclampsia in the first trimester of pregnancy using machine learning algorithms. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (10): 94-107 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.101

- Chen Y., Shi X., Wang Z., Zhang L. Development and validation of a spontaneous preterm birth risk prediction algorithm based on maternal bioinformatics: a single-center retrospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024; 24(1): 763. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06933-x

- Zhang Y., Du S., Hu T., Xu S., Lu H., Xu C. et al. Establishment of a model for predicting preterm birth based on the machine learning algorithm. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023; 23(1): 779. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-06058-7

- Sun Q., Zou X., Yan Y., Zhang H., Wang S., Gao Y. et al. Machine learning-based prediction model of preterm birth using electronic health record. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022; 2022: 9635526. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2022/9635526

- Mavrogiorgou A., Kiourtis A., Kleftakis S., Mavrogiorgos K., Zafeiropoulos N., Kyriazis D. A catalogue of machine learning algorithms for healthcare risk predictions. Sensors (Basel). 2022; 22(22): 8615. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/s22228615

- Hicks S.A., Strümke I., Thambawita V., Hammou M., Riegler M.A., Halvorsen P. et al. On evaluation metrics for medical applications of artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2022; 12(1): 5979. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09954-8

- Liu T., Krentz A., Lu L., Curcin V. Machine learning based prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk using electronic health records data: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health. 2024; 6(1): 7-22. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztae080

- Khandre V., Potdar J., Keerti A. Preterm birth: an overview. Cureus. 2022; 14(12): e33006. https://dx.doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33006

- Фомина А.С. Преждевременные роды, современные реалии. Научные результаты биомедицинских исследований. 2020; 6(3): 434-46. [Fomina A.S. Premature birth, modern realities. Research Results in Biomedicine. 2020; 6(3): 434-46 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18413/2658-6533-2020-6-3-0-12

Received 12.08.2025

Accepted 16.12.2025

About the Authors

Yuliya S. Boldina, PhD Student, Senior Lecturer at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Dermatovenereology of the Medical Institute, Petrozavodsk State University; Obstetrician-Gynecologist, Republican Perinatal Center named after K.A. Gutkin, 31, Krasnoarmeyskaya str., Petrozavodsk, Republic of Karelia, 185035, Russia,+7(981)405-85-24, ulia.isakova94@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1450-650X

Alexander A. Ivshin, PhD, Associate Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dermatovenerology of the Medical Institute, Petrozavodsk State University, 31, Krasnoarmeyskaya str., Petrozavodsk, Republic of Karelia, 185035, Russia, +7(909)567-12-51, scipeople@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7834-096X

Kristina S. Svetova, MSc student in Computer Engineering at the Department of Information Engineering (DEI), University of Padua, Via Giovanni Gradenigo 6/b,

35131 Padova, Italy, +39 379-150-89-87, ksvetova16@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5552-638X

Corresponding author: Alexander A. Ivshin, scipeople@mail.ru