Effectiveness of vaginal metroplasty for treating cesarean scar defect: a comparative analysis of techniques

Malushko A.V., Fatkullina I.B., Shchedrina I.D., Alekseev S.M., Silakova V.R.

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of metroplasty via vaginal access in patients with uterine scar after cesarean section (CS).

Materials and methods: This comparative prospective study included 100 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of cesarean scar defect who were planning to become pregnant. The first group of patients (n=50) underwent metroplasty using vaginal access, 10 patients underwent laparotomy (group 2), and the third group (n=40) underwent metroplasty using traditional laparoscopic access. All patients in the study groups were evaluated based on the following criteria: complaints; condition of the uterine scar six months after surgery, as determined by ultrasound data; duration of surgery; amount of blood loss; characteristics of the pain syndrome experienced in the first six hours after surgery; and presence of complications. A comparative analysis of the results of the three surgical treatment methods was conducted.

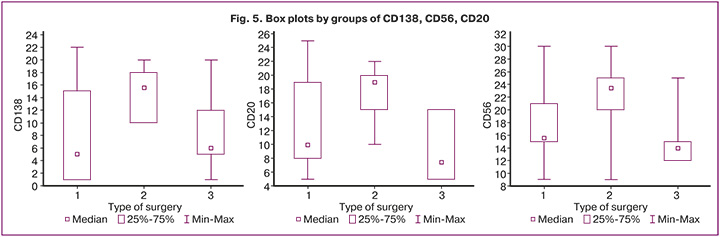

Results: The following characteristics were identified in the study groups: after CS, the main complaints included menstrual cycle disorders, such as prolonged spotting after menstruation, heavy and frequent menstruation with a regular cycle (menorrhagia, polymenorrhea), painful menstruation, and secondary infertility. Following metroplasty in the study groups, clinical manifestations regressed in all patients after six months. The mean minimum thickness of the myometrium in the scar area increased significantly: in group 1, it ranged from 3.8 to 5.35 mm with a mean value of 5.3 (0.8) mm; in group 2, it ranged from 4.5 to 5.2 mm with a mean value of 4.9 (0.3) mm; and in group 3, it ranged from 3.8 to 5.3 mm with a mean value of 4.7 (0.5) mm. The “scar thickness, mm” indicator dynamics were significantly different before and after metroplasty in all the study groups (p<0.0001). The use of the vaginal method of uterine scar correction showed comparable results, with the following features noted: the duration of the operation in group 1 ranged from 20 to 55 min, with a median time of 35 (30; 40) min; in group 2, the duration of the operation ranged from 75 to 120 min, with a median time of 95 (90; 120) min; and in group 3, the duration of the operation ranged from 70 to 135 min, with a median time of 95 (90; 110) min. This is associated with a more technically simplified surgical correction technique that does not require a laparoscopic stand. Group 1 differed significantly from groups 2 and 3 (p1,2=0.0003 and p1,3<0.0001, respectively). The following features were identified when assessing the severity of pain syndrome using VAS: in group 1, the VAS score ranged from 1 to 5 points, with a median of 2 (2; 3); in group 2, it ranged from 6 to 7 points, with a median of 6 (6; 7); and in group 3, it ranged from 4 to 6 points, with a median of 5 (4; 5). Group 1 significantly differed from groups 2 and 3 (p1,2= 0.00002 and p1,3= 0.00030, respectively), whereas groups 2 and 3 did not differ significantly in terms of VAS scores (p2,3= 0.79). Histological examination of the uterine scar in the study material revealed moderate to severe expression of markers of chronic endometritis (CD 138, CD 56, and CD 20), indicating a chronic inflammatory process, concurrent infertility, miscarriage, and failed in vitro fertilization attempts. In several cases, endometrioid lesions were observed in the study material.

Conclusion: The study demonstrated that vaginal access metroplasty is highly effective and has certain advantages over traditional laparoscopic techniques. Therefore, it can be considered the preferred surgical treatment option in areas with limited resources and appropriately qualified specialists.

Authors' contributions: Malushko A.V., Fatkullina I.B., Alekseev S.M. – conception and design of the study; Shchedrina I.D., Malushko A.V., Silakova V.R. – data collection and analysis; Shchedrina I.D., Malushko A.V. – statistical analysis, drafting of the manuscript; Fatkullina I.B., Malushko A.V., Alekseev S.M. – editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Leningrad Regional Clinical Hospital.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Malushko A.V., Fatkullina I.B., Shchedrina I.D., Alekseev S.M., Silakova V.R. Effectiveness of

vaginal metroplasty for treating cesarean scar defect: a comparative analysis of techniques.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (11): 86-94 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.206

Keywords

Cesarean scar defects are significant clinical and gynecological issues that profoundly affect women's reproductive health. Researchers have indicated that the prevalence of pathological niche formation (myometrial thinning in the scar area) ranges from 19% to 61% following repeat cesarean sections (CS) and may present with clinical manifestations such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), pain syndrome, chronic endometritis, and secondary infertility [1, 2].

Modern surgical approaches to correct cesarean scar defects include laparotomy, laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, and vaginal metroplasty [2].

In recent years, there has been growing interest in vaginal access as a promising method for the surgical correction of cesarean scar defects. Publications from both domestic and international authors indicate that vaginal metroplasty yields favorable clinical and reproductive outcomes with minimal trauma [2–4]. The advantages of this technique include a shorter operation time, reduced blood loss, quicker recovery, and absence of visible postoperative scarring [4, 5]. One study reported a fertility rate of 67% in patients following excision of the uterine scar via vaginal access [6].

In this context, the development and implementation of a new, highly effective method of vaginal metroplasty, which is simplified in terms of technique and requires minimal equipment, is of particular interest.

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of vaginal metroplasty in patients with uterine scars after CS.

Materials and methods

This prospective study was conducted in the Gynecology Department of the Leningrad Regional Clinical Hospital. The study included 100 patients of reproductive age with clinical signs of cesarean scar defects from 2021 to 2024 who were planning a pregnancy. The main inclusion criteria were complaints of menstrual cycle disorders, such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), secondary infertility, detection of cesarean scar defects, niches in the scar area according to ultrasound (US) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data, and residual myometrium thickness of less than 2 mm. All patients underwent surgical correction (metroplasty) based on an assessment of the severity of the niche (according to the Clinical Guidelines, 2024) scoring 5–6 points.

Patients were randomly divided into groups based on the method of surgical access: group 1 (n=50) included patients who underwent metroplasty using the original technique, patent RU2840188C1 [7]; group 2 (n=10) included those with laparotomy access; and group 3 (n=40) included patients who underwent laparoscopic scar correction.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age 20–44 years, history of at least one cesarean section, niche volume greater than 0.1 cm³, residual myometrium thickness in the scar area of less than 2 mm, and complaints (menstrual cycle disorders, AUB, and infertility). The exclusion criteria were the presence of malignant tumors of the uterus and ovaries, inflammatory diseases of the pelvic organs, decompensated somatic and endocrine diseases, pregnancy at the time of examination, and patient refusal to participate in surgical treatment and research.

Before surgery, all patients underwent standard clinical and laboratory examinations, transvaginal ultrasound, and, in some cases, MRI to assess uterine scarring, the presence and size of the “niche,” and thickness of the residual myometrium.

The study evaluated several indicators, including the medical history of patients in the observation groups, duration of the operation, volume of intraoperative blood loss, presence and frequency of intra- and postoperative complications, severity of pain syndrome on a visual analog scale (VAS), changes in myometrial thickness and niche volume six months after surgery, and regression of complaints.

Method for performing metroplasty via vaginal access

The surgery was performed under neuraxial anesthesia. The patient was positioned with the pelvic end hanging 3–5 cm off the table and arms placed along the body. The legs were bent at 90° at the hip and knee joints, with rotation at the knee joints and abduction to the sides at 45°.

A speculum and elevator were inserted into the vagina, and the cervix was grasped using bullet forceps. The uterine cavity was probed, and the cervical canal was dilated to a size of 9 using Hegar dilators. A hysteroscope was then inserted into the uterine cavity, allowing detailed examination of the uterine cavity and scar area on the anterior wall. This helped determine the location, assess the distance from the cervical canal to the scar, evaluate the size and volume of the “niche,” and confirm the presence of scar dehiscence.

Surgical access to the scar area was obtained through the vagina. The transition fold area and access lines were determined. Using a scalpel or Cooper's scissors, an anterior colpotomy was performed 1 cm above the level of the external os of the cervix (along the transition fold). Next, a sharp instrument was used to shift the bladder upward, allowing the surgeon to work in the desired layer on a “white field.” The incision was arc-shaped and covered the anterior semicircle of the cervix. After exposing the area, vicryl ligatures (70 cm long, 0 mm thick, with a 30 mm diameter cutting needle) were applied to the anterior lip of the cervix. The tension of these ligatures pulled the cervix upward, enabling clear visualization of the scar on the uterus by sequentially repositioning the ligatures until the scar was visible. After accurately visualizing the defect area and thinning the scar zone, two additional Vicryl ligatures were applied – one in front of and one behind the scar. The tension from these threads pulled the scar into the surgical field.

The scar area was visualized using a uterine probe. The probe can be used to perforate the area of scar thinning or to excise the scar tissue with a sharp, thin scalpel in a transverse direction while applying tension to the area, without any coagulation. A Hegar dilator No. 5–6 was inserted into the uterine cavity to prevent ligatures from being applied to the anterior and posterior walls of the cervical canal. The scar area was sutured with separate Vicryl sutures in the vertical direction to ensure reliable connection of the wound edges in two rows. Subsequently, the integrity of the scar was checked using a hysteroscope, and the vaginal mucosa was sutured with separate vicryl sutures.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 10.0. Arithmetic mean (Mean) and standard deviation (SD) were used to describe quantitative data with a normal distribution (age, duration of surgery, number of bed days, etc.). For variables that deviated from a normal distribution (e.g., OTM values), the median (Me) and quartiles (Q25; Q75) were used. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was applied to compare two independent samples, particularly the parameters of pelvic ultrasound in women six months after surgery and the severity of the immunohistochemical marker expression. For categorical variables, contingency tables and Pearson's χ² test or Fisher's exact test (for small cells counts) were used to assess the significance of differences. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

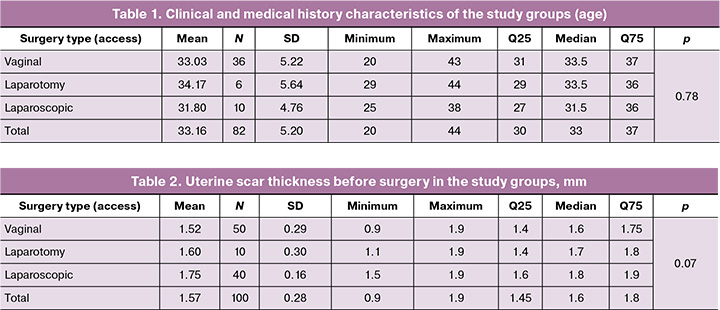

Analysis of clinical and medical history data from the study groups revealed that the patients' ages ranged from 20 to 44 years, with a mean age of 33.2 (5.2) years: 33.0 (5.2) years in group 1, 34.2 (5.6) years in group 2, and 31.8 (4.8) years in group 3. The groups were comparable in terms of age (p=0.78) (Table 1).

The patients in the study groups were also comparable in terms of body mass index, age at menarche, obstetric and gynecological history, and somatic history; no distinctive features were identified.

The study groups exhibited the following characteristics: after cesarean section (CS), the primary complaints included menstrual cycle disorders such as prolonged spotting after menstruation, heavy and frequent menstruation with a regular cycle (AUB, menorrhagia, polymenorrhea), painful menstruation, and secondary infertility.

The distribution of the “menstrual cycle disorder” indicator by group was as follows: in group 1, 35/50 (69.4%) patients had such complaints; in group 2, 5/10 (50.0%); and in group 3, 25/40 (70.0%). The groups were homogeneous in terms of this indicator (p=0.20, Fisher's exact test).

The distribution of the AUB indicator across groups was as follows: in group 1, 25/50 (50.0%) patients had AUB; in group 2, 7/10 (66.7%); and in group 3, 25/40 (70.0%). The groups were comparable in terms of this variable (p=0.52, Fisher's exact test).

The distribution of the “painfulness” indicator by group was as follows: in group 1, 15/50 (27.8%) patients had painful menstruation; in group 2, 4/10 (33.3%) patients had painful menstruation; and in group 3, 15/40 (30.0%) patients had painful menstruation. The groups did not differ significantly in terms of this indicator (p=0.91, Fisher's exact test).

The distribution of the “infertility 2” indicator by group was as follows: in group 1, there were 18/50 (27.8%) patients with this type of infertility; in group 2, 5/10 (50.0%); and in group 3, 10/40 (30.0%). The groups were homogeneous in terms of this indicator (p=0.52, Fisher's exact test).

The thickness of the uterine scar before surgery in group 1 (vaginal access) ranged from 0.9 to 1.9 mm with a mean of 1.5 (0.3) mm, in group 2 (laparotomy access) – from 1.1 to 1.9 mm with a mean of 1.6 (0.3) mm, and in group 3 (laparoscopic access) – from 1.5 to 1.9 mm with a mean of 1.8 (0.2) mm. The groups did not differ significantly (p=0.07) (Table 2).

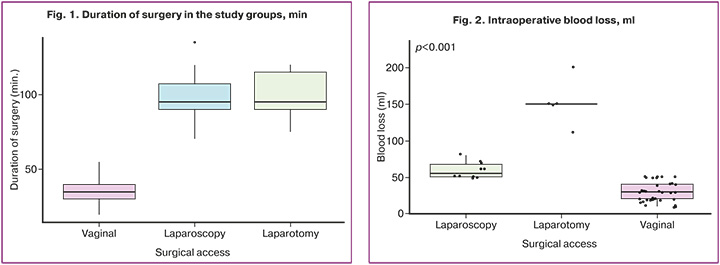

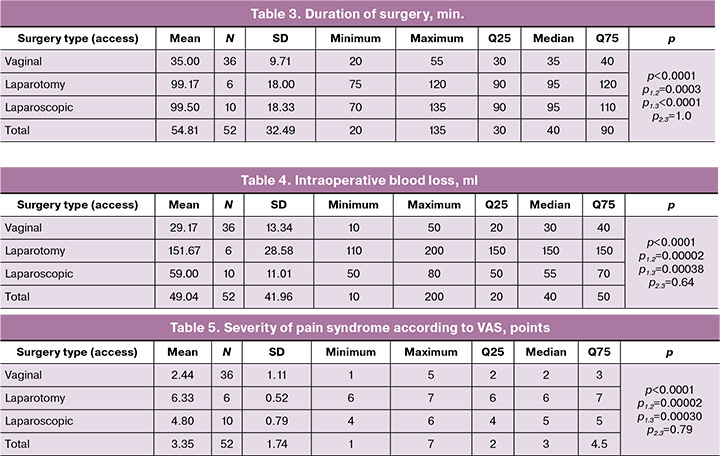

The duration of the operation in group 1 (vaginal access) ranged from 20 to 55 min, with a median time of 35 (30; 40) min; in group 2 (laparotomy access), from 75 to 120 min, with a median time of 95 (90; 120) min; and in group 3 (laparoscopic access), from 70 to 135 min, with a median time of 95 (90; 110) min. The groups differed significantly in this indicator (p<0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test), as illustrated in Figure 1. At the same time, group 1 differed significantly from groups 2 and 3 (p1,2=0.0003 and p1,3<0.0001, respectively), while no significant differences were found between groups 2 and 3 (p2,3=1.0) (Table 3, Fig. 1).

The intraoperative blood loss indicator in the study groups varied: in group 1 (vaginal access) – from 10 to 50 ml, with a median of 30 (20; 40) ml, in group 2 (laparotomy access) – from 110 to 200 ml with a median of 150 (150; 150) ml, in group 3 (laparoscopic access) – from 50 to 80 ml with a median of 55 (50; 70) ml. The groups differed significantly in this indicator (p<0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test). At the same time, group 1 differed significantly from groups 2 and 3 (p1,2=0.00002 and p1,3=0.00038, respectively), while groups 2 and 3 (p2,3=0.64) did not differ significantly in terms of intraoperative blood loss (Table 4, Fig. 2).

When assessing the severity of pain syndrome using VAS, the following features were identified: in group 1 (vaginal access), the VAS value ranged from 1 to 5 points, with a median of 2 (2; 3); in group 2 (laparotomy access), from 6 to 7 points with a median of 6 (6; 7); and in group 3 (laparoscopic access), from 4 to 6 points with a median of 5 (4; 5) points. The groups differed significantly in this indicator (p<0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test). At the same time, group 1 differed significantly from groups 2 and 3 (p1,2=0.00002 and p1,3=0.00030, respectively), while groups 2 and 3 (p2,3=0.79) did not differ significantly in terms of VAS (Table 5).

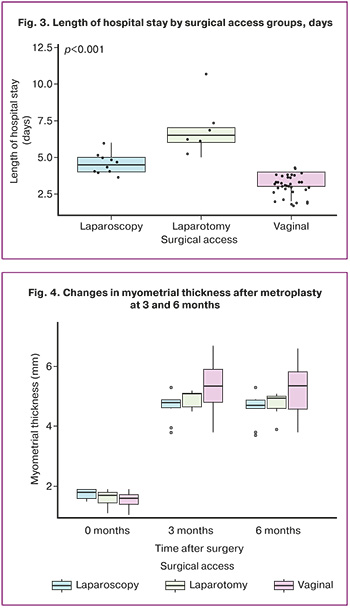

The following features were identified in the study groups in terms of length of hospital stay: in group 1 (vaginal access), the length of hospital stay ranged from 2 to 4 days, with a median of 3 (3; 4) days; in group 2 (laparotomy access) – from 5 to 11 days with a median of 6.5 (6; 7) days; and in group 3 (laparoscopic access) – from 4 to 6 days with a median of 4.5 (4; 5) days. The groups differed significantly in this indicator (p<0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test), as illustrated in Figure 3. At the same time, group 1 differed significantly from groups 2 and 3 (p1,2=0.00003 and p1,3=0.00073, respectively), while groups 2 and 3 (p2,3=0.65) did not differ significantly from each other (Table 6, Fig. 3).

No intraoperative or postoperative complications were observed during follow-up.

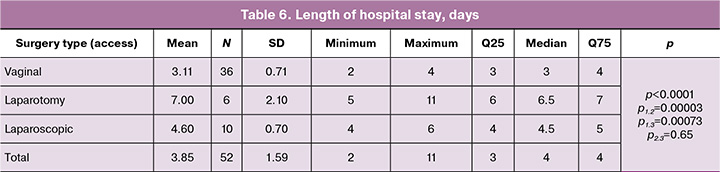

The thickness of the uterine postoperative scar 6 months after surgery in group 1 (vaginal access) ranged from 3.8 to 5.35 mm, with a mean of 5.3 (0.8) mm; in group 2 (laparotomy access), it ranged from 4.5 to 5.2 mm, with a mean of 4.9 (0.3) mm; and in group 3 (laparoscopic access), it ranged from 3.8 to 5.3 mm, with a mean of 4.7 (0.5) mm. The groups did not differ significantly in this indicator (p=0.09) (Fig. 4).

The dynamics of scar thickness (mm) before surgery and 3 and 6 months after surgery are shown in Figure 4. The dynamics of this indicator were significant (p<0.0001), and the dynamics of the groups differed significantly (p=0.004).

Six months after metroplasty, there were no complaints of menstrual cycle disorders, abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), or painful menstruation.

This study examined the expression of markers for chronic endometritis (CD 138, CD 56, and CD 20) in excised uterine scars following cesarean section. The study material revealed moderate to pronounced expression of these markers (Fig. 5), indicating a chronic inflammatory process and signs of chronic endometritis, which are associated with infertility, miscarriage, and unsuccessful in vitro fertilization attempts. In several cases, areas of endometrioid lesions were identified in the study materials.

Discussion

Cesarean scar defects continue to be a relevant clinical issue, necessitating an individualized approach to the selection of surgical correction methods. Various techniques for metroplasty have been documented in the literature, including laparotomy, laparoscopy, hysteroscopy, and vaginal access, each with its own characteristics, indications, and limitations.

Traditionally, laparotomy metroplasty has been widely used but is associated with a high degree of maternal trauma. This approach can result in significant blood loss (up to 300 ml or more), severe pain, and prolonged postoperative recovery. Additionally, open surgery necessitates general anesthesia, and an incision in the anterior abdominal wall can lead to the formation of a rough postoperative scar, which diminishes patient satisfaction with the cosmetic outcomes [8].

The laparoscopic method, as described by Bryunin D.V. et al. (2018), offers a less invasive alternative, allowing for precise identification and suturing of the defect area. However, despite its clear advantages, this technique requires expensive equipment, considerable operating time, and a highly skilled surgeon. Moreover, applying an endoscopic suture to the myometrium is technically challenging, which may increase the operative duration and the risk of inadequate reconstruction of the defect area [1, 9].

Hysteroscopic correction is utilized to a limited extent, primarily for the removal of niche elements or adhesions, according to clinical recommendations (2024). It does not facilitate complete suturing of the myometrium, as supported by the findings of Stavridis K. et al. (2025) [3, 9]. This limitation renders the method ineffective in cases of severe defects (less than 2 mm thickness of residual myometrium), particularly in patients with reproductive goals.

Data on the application of vaginal access are particularly significant. Reconstructive surgery through the vagina avoids entering the abdominal cavity, thereby reducing blood loss and shortening the duration of the operation. The technique is well tolerated by patients, is associated with low levels of postoperative pain, and results in shorter hospital stays [6, 7, 10].

The results obtained in this study align with the findings of both domestic and international studies, demonstrating the high effectiveness of vaginal access while maintaining minimal invasiveness and good control over the anatomical reconstruction of the scar [9, 11–14].

Conclusion

The analysis indicates that vaginal access for cesarean scar defect metroplasty is an effective and minimally invasive alternative to laparoscopic surgery. Compared with other surgical correction methods, it shows superior results in several key criteria: reduced operation duration, minimal blood loss, and low severity of postoperative pain. The effectiveness of the correction was validated by a significant increase in the thickness of the residual myometrium, alongside the elimination or considerable reduction in the severity of the niche.

In contrast to laparoscopy, vaginal access does not necessitate expensive equipment or complex endoscopic procedures, does not require general anesthesia, and avoids trauma to the abdominal cavity, making it a safe and accessible option even for patients with concurrent somatic diseases.

Therefore, vaginal metroplasty can be regarded as the method of choice for patients with clinically significant cesarean scar defects, especially in contexts where minimizing invasiveness, reducing hospitalization duration, and decreasing the resource intensity of surgical treatment are priorities. The data collected support the recommendation for broader implementation of this approach in clinical practice, given that the patient selection criteria and appropriate surgeon training are adhered to.

References

- Брюнин Д.В., Михаелян Н.С., Хохлова И.Д., Джибладзе Т.А., Ищенко А.И., Горбенко О.Ю., Гаврилова Т.В., Гадаева И.В. Опыт лапароскопической коррекции несостоятельности рубца на матке после операции кесарева сечения. Архив акушерства и гинекологии им. В.Ф. Снегирева. 2018; 5(3): 148-53. [Bryunin D.V., Mikhayelyan N.S., Khokhlova I.D., Dzhibladze T.A., Ishchenko A.I., Gorbenko O.Yu., Gavrilova T.V., Gadaeva I.V. Experience of laparoscopic correction of failure of the uterine scar after the cesarean operation. V.F. Snegirev Archives of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Russian journal. 2018; 5(3): 148-53 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18821/2313-8726-2018-5-3-148-153

- Подзолкова Н.М., Демидов А.В., Осадчев В.Б., Бабков К.В., Денисова Ю.В. Истмоцеле: дискуссионные вопросы терминологии, диагностики и лечения. Гинекология. 2024; 26(2): 119-27. [Podzolkova N.M., Demidov A.V., Osadchev V.B., Babkov K.V., Denisova Yu.V. Isthmocele: controversial issues of terminology, diagnosis and treatment. A review. Gynecology. 2024; 26(2): 119-27 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.26442/20795696.2024.2.202716

- Stavridis K., Balafoutas D., Vlahos N., Joukhadar R. Current surgical treatment of uterine isthmocele: an update of existing literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025; 311(1): 13-24. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-024-07880-w

- Радзинский В.Е., Давыдов А.И., Хамошина М.Б., Лебедева М.Г., Апресян С.В. Истмоцеле: спорное и нерешенное. Вопросы гинекологии, акушерства и перинатологии. 2025; 24(1): 5-14. [Radzinsky V.E., Davydov A.I., Khamoshina M.B., Lebedeva M.G., Apresyan S.V. Isthmocele: controversial and unresolved issues. Gynecology, Obstetrics and Perinatology. 2025; 24(1): 5-14. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.20953/1726-1678-2025-1-5-14

- Zhou X., Yang X., Chen H., Fang X., Wang X. Obstetrical outcomes after vaginal repair of caesarean scar diverticula in reproductive-aged women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18(1): 407. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2015-7.

- Deng K., Liu W., Chen Y., Lin S., Huang X., Wu C. et al. Obstetric and gynecologic outcomes after the transvaginal repair of cesarean scar defect in a series of 183 women. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021; 28(5): 1051-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2020.12.009.

- Патент 2840188 C1 Российская Федерация, МПК A61B 17/42, A61B 17/04. Способ вагинальной метропластики несостоятельного рубца на матке после операции кесарева сечения / С.М. Алексеев, А.В. Малушко, Э.В. Комличенко [и др.]. Заявл. 29.10.2024, опубл. 19.05.2025. [Patent 2840188 C1 Russian Federation, IPC A61B 17/42, A61B 17/04. Method of vaginal metroplasty of a failed uterine scar after cesarean section surgery/S.M. Alekseev, A.V. Malushko, E.V. Komlichenko [et al.]. Declared 29.10.2024 publ. 19.05.2025. (in Russian)].

- Гарифуллова Ю.В., Журавлева В.И. Редкий клинический случай формирования несостоятельного рубца на матке после кесарева сечения в позднем послеоперационном периоде. Практическая медицина. 2020; 18(2): 74-7. [Garifullova Yu.V., Zhuravleva V.I. Rare clinical case of uterine scar dehiscence after cesarean section in late postoperative period. Practical Medicine. 2020; 18(2): 74-7. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.32000/2072-1757-2020-2-74-77

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Послеоперационный рубец на матке, требующий предоставления медицинской помощи матери во время беременности, родов и в послеродовом периоде. 2024. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Postoperative uterine scar requiring provision of maternal medical care during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period. 2024. (in Russian)].

- Малушко А.В., Фаткуллина И.Б., Щедрина И.Д., Алексеев С.М., Силакова В.Р. Сравнение хирургических методик коррекции дефекта рубца на матке после операции кесарева сечения. Главный врач Юга России. 2025; 4(102): 16-9. [Malushko A.V., Fatkullina I.B., Shchedrina I.D., Alekseev S.M., Silakova V.R. Comparison of surgical techniques for correcting uterine scar defect after cesarean section surgery. Glavnyj vrach Yuga Rossii. 2025; 4(102): 16-9 (in Russian)].

- Филиппов Е.Ф., Пирожник Е.Г., Мелконьянц Т.Г., Тарабанова О.В., Ордокова А.А., Соколова Е.И., Попова Н.А. Опыт использования трансвагинального экстраперитонеального доступа в хирургическом лечении несостоятельности рубца на матке после кесарева сечения. Кубанский научный медицинский вестник. 2018; 25(1): 40-5. [Filippov E.F., Pirozhnik E.G., Melkonyants T.G., Tarabanova O.V., Ordokova A.A., Sokolova E.I., Popova N.A. Experience of transvaginal extraperitoneal approach in surgical treatment of uterine scar leak after caesarean section. Kubanskij nauchnyj medicinskij vestnik. 2018; 25(1): 40-5. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2018-25-1-40-45

- Verberkt C., Klein Meuleman S.J.M., Ket J.C.F., van Wely M., Bouwsma E., Huirne J.A.F. Fertility and pregnancy outcomes after a uterine niche resection in women with and without infertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. F S Rev. 2022; 3(3):174-89. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.xfnr.2022.05.003.

- He Y., Zhong J., Zhou W., Zeng S., Li H., Yang H. et al. Four surgical strategies for the treatment of cesarean scar defect: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020; 27(3): 593-602. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.03.027

- Малушко А.В., Фаткуллина И.Б., Щедрина И.Д., Алексеев С.М., Силакова В.Р., Федорова М.В. Влагалищный доступ в коррекции несостоятельности рубца на матке. Практическая медицина. 2025; 23(4): 35-40. [Malushko A.V., Fatkullina I.B., Shchedrina I.D., Alekseyev S.M., Silakova V.R., Fedorova M.V. Vaginal access in the correction of uterine scar failure. Practical Medicine. 2025; 23(4): 35-40. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.32000/2072-1757-2025-4-35-40

Received 30.07.2025

Accepted 05.11.2025

About the Authors

Anton V. Malushko, obstetrician-gynecologist, Head of Gynecological Department, Leningrad Regional Clinical Hospital, 194291, Russia, St. Petersburg, Lunacharsky Ave.,45, bldg. 2, litera A, +7(812)670-18-88, a-malushko@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4460-9075

Irina B. Fatkullina, Dr. Med. Sci., Deputy Chief Physician for Obstetrics and Gynecology, Republican Clinical Perinatal Center, Ministry of Health of the Republic of Bashkortostan; Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Bashkir State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 450008, Russia, Ufa,

Lenin str., 3, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5723-2062

Irina D. Shchedrina, PhD, obstetrician-gynecologist at the Gynecological Department, Leningrad Regional Clinical Hospital, 194291, Russia, St. Petersburg, Lunacharsky Ave., 45, bldg. 2, litera A, +7(982)651-42-98, forgottenz@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0062-1256

Sergey M. Alekseev, PhD, Chief Oncologist and Chief Hematologist of the Leningrad Region, Chief Physician, Leningrad Regional Clinical Hospital, 194291, Russia,

St. Petersburg, Lunacharsky Ave., 45, bldg. 2, litera A, bmt312@gmail.com

Valeriia R. Silakova, student at the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia

(Sechenov University), 119021, Russia, Moscow, Rossolimo str., 11, bldg. 2, +7(499)245-27-79, lerasilakova1108@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0390-7525

Corresponding author: Irina D. Shchedrina, forgottenz@mail.ru