Uterine scar: cesarean section or vaginal birth? Impact on reproductive outcomes

Mateykovich E.A., Karpova I.A., Shevlyukova T.P., Topchiu I.F., Bratova O.V., Marchenko R.N., Polyakova V.A.

Objective: To study the criteria used to select pregnant women with a uterine scar following a cesarean section (CS) for vaginal birth (VB) in level 2 maternity hospitals and to evaluate the effectiveness of these criteria in relation to birth outcomes.

Materials and methods: This study was conducted at Maternity Hospital No. 3, a level 2 maternity hospital in Tyumen, which provides specialized, round-the-clock medical care for pregnant women. The study included 182 pregnant women with uterine scars from one CS who were observed between 2021 and 2023. Depending on the birth outcomes, the patients were divided into three groups: Group 1 included 85 women with a uterine scar who gave birth vaginally; group 2 included 45 women with a uterine scar who were admitted for VB but ultimately gave birth via CS (unsuccessful VB); and group 3 included 52 women with a uterine scar who underwent CS immediately. Clinical and anamnestic data, as well as the course of pregnancy and childbirth, were compared between these groups.

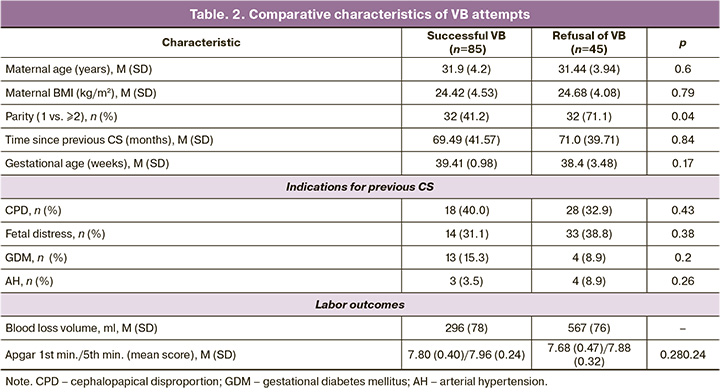

Results: The primary reason for operative delivery among pregnant women with uterine scars was the refusal of VB by the patients (n=45, 86.0%). Reasons for refusal included concerns about the child’s health due to complications, such as fetal hypoxia (n=20, 44.4%), labor dystocia (n=19, 42.2%), clinically narrow pelvis (n=4, 8.9%), and premature rupture of membranes (n=2, 4.4%). A comparison of successful and unsuccessful VB attempts that ended in surgical delivery revealed no statistically significant differences between the two patient groups in terms of maternal age, body mass index, time since the last childbirth, or gestational age. However, the gestational age was significantly lower in cases of VB refusal than in those with successful VB. The parity at birth was statistically significant. Most patients in the successful VB group had two or more previous births, whereas more than two-thirds of the births in the unsuccessful VB group had only second births (p=0.04).

Conclusion: Reproductive experience suggests that vaginal delivery is the better option. Careful monitoring of these births aids in the development of effective criteria for successful VB in women with uterine scars, thereby increasing their chances of having multiple children and addressing urgent demographic policy issues.

Authors' contributions: Mateikovich E.A., Topchiu I.F., Bratova O.V., Polyakova V.A. – article concept; Mateikovich E.A. – literature review, drafting of the manuscript; Mateikovich E.A., Topchiu I.F., Bratova O.V. – collection of empirical material; Mateikovich E.A., Karpova I.A., Shevlyukova T.P., Marchenko R.N. – material analysis; Mateikovich E.A., Topchiu I.F. – statistical analysis.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Tyumen SMU, Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Mateykovich E.A., Karpova I.A., Shevlyukova T.P., Topchiu I.F., Bratova O.V., Marchenko R.N., Polyakova V.A. Uterine scar: cesarean section or vaginal birth? Impact on reproductive outcomes.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (5): 78-85 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.13

Keywords

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the ideal rate of caesarean section (CS) to be between 10% and 15%. This rate is effective in saving the lives of mothers and infants but only when CS is medically necessary. A CS rate exceeding 10% does not correlate with a reduction in maternal and infant mortality rates; instead, it may lead to significant, sometimes permanent, complications, disabilities, or even death. The WHO emphasizes that efforts should focus on providing CS to those in need rather than aiming for a specific rate [1]. Nevertheless, the global rate of CS has been gradually increasing, particularly in developed countries, and has doubled since 2000. The current global rate is approximately 21.7% [2], with many developed nations reporting rates exceeding 30% [3, 4]. Women often choose CS due to fear of pain, desire to minimize childbirth complications, ability to plan the delivery date, and assurance of a healthy child [5]. Efforts to reduce the frequency of CS have largely been unsuccessful, partly due to a legal climate in which negative expert assessments of adverse obstetric outcomes are frequently linked to inappropriate delivery strategies via the natural birth canal. The "defensive medicine" syndrome compels obstetricians and gynecologists to opt for abdominal delivery more often to avoid criminal charges and lawsuits [6, 7].

In the early 1970s, a stereotype emerged: "once a CS, always a CS." However, since the mid-1970s, as CS rates have increased, the incidence of vaginal births (VB) after CS has also increased. From 1985 to 1995, the VB rate increased by 20%, leading to a decrease in the CS rates. Unfortunately, this increase in VB also results in more complications and subsequent malpractice claims, causing the proportion of VB among delivery methods to decline [8]. Consequently, repeated CS remains the primary delivery method for women with uterine scars, and the rate of VB after CS remains low; in the USA, it does not reach 10% [9].

In the Russian Federation, uterine scarring is not an absolute indication for operative delivery [10], but it is the leading factor driving repeated CS [11]. This obstetric strategy creates a vicious cycle: an increase in CS rates leads to more women with multiple uterine scars, which in turn heightens the risks for those planning to have many children [8].

Complications of pregnancy and childbirth in women with a uterine scar include pregnancy in a scarred uterus, placenta previa, placenta accreta, and obstetric hemorrhage [12]. The uterine scar following CS is the leading cause of uterine rupture [13].

The success rate of VB after CS ranges from 46.0% to 73.9%. Common complications associated with VB after CS include low birth weight infants (approximately 21%), an Apgar score of less than 7 at one minute (approximately 24%), and neonatal intensive care unit admissions (approximately 5.1%) [14]. The success of a VB attempt after a CS cannot be guaranteed. While VB after CS generally presents fewer complications than planned repeat CS, an unsuccessful VB attempt (requiring emergency CS due to failure to deliver vaginally) carries a higher risk of complications than planned repeat CS [15].

Research to identify the predictors of successful and unsuccessful VB attempts is ongoing. These predictors include previous reasons for CS, intraoperative complications, interval between pregnancies, and current obstetric factors such as gestational age, fetal size, and Bishop score prior to delivery [16]. Healthcare organizations offering VB after CS must have adequate human and material resources to perform emergency CS [8].

In the Russian Federation, VB after CS is permissible in selected level 2 maternity hospitals, provided that there is the necessary infrastructure, organizational conditions, and a sufficient number of experienced personnel, and in the absence of indications for transfer to a level 3 facility [17]. Urgent and emergency CS, including cases of unsuccessful VB attempts, is typically conducted in maternity hospitals, where pregnant women are located at the time of diagnosis [18].

This study aimed to investigate the criteria used to select pregnant women with uterine scars following CS for vaginal delivery in level 2 maternity hospitals and to evaluate the effectiveness of these criteria for birth outcomes.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted at Tyumen Maternity Hospital No. 3, a second-level obstetric facility that provides specialized round-the-clock medical care to pregnant women in the Tyumen oblast, primarily in the regional center. Patients are admitted on both a planned and emergency basis.

This study included 182 pregnant women with a uterine scar from one previous CS, who were observed between 2021 and 2023. The inclusion criteria were singleton pregnancy, competent scar as assessed by ultrasound, one prior CS, placental location outside the uterine scar, and informed consent to participate.

Based on birth outcomes, the patients were divided into three groups: group 1 included 85 women with a uterine scar who delivered vaginally; group 2 comprised 45 women with a uterine scar who were admitted for VB but ultimately underwent CS due to unsuccessful VB; and group 3 included 52 women with a scar who either refused VB or had contraindications for VB, as per the clinical guidelines "Singleton birth, delivery by cesarean section" [10].

Statistical analysis

Data collection and statistical mapping were performed using MS Excel 2019 (Microsoft, USA). Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistica Basic Academic 13 Ru program. Intergroup comparisons of continuous variables were performed after determining the type of distribution in each group using an analysis of variance. For samples with 50 or fewer observations (ranging from 8 to 50), the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed; for samples exceeding 50, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Lilliefors tests were used. The null hypothesis was accepted (indicating no differences between the studied distribution and a normal distribution) if the significance (p) of the hypothesis test exceeded 0.05, and it was rejected (indicating a difference from normality) if p was less than 0.05. Continuous variables showing a normal distribution are expressed as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). The significance of differences (p) was evaluated using the Student's t-test, assuming a normal distribution of variations and homogeneity of variances.

Results

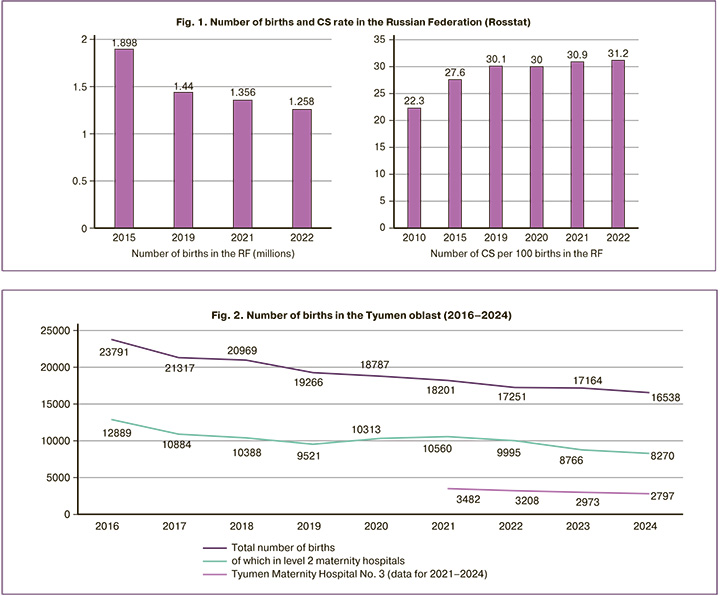

According to Rosstat, the number of births in the Russian Federation decreased by 33.7% from 2015 to 2022. In other words, the number of births decreased by more than one-third over the seven years. This is a widely discussed trend in the context of challenges in implementing demographic policies.

Conversely, the frequency of CSs increases. This upward trend only changed to a downward trend in 2020. Over seven years, the growth rate was more than 28.5%. Nearly one-third of pregnant women in Russia gave birth abdominally (Fig. 1) [19].

In the Tyumen oblast (excluding the Khanty-Mansiysk and Yamalo-Nenets autonomous okrugs), the number of births has shown a negative trend over the past seven years, similar to the all-Russia trend. More than half of the births occurred in level 2 obstetric hospitals, which have also recorded negative dynamics for seven years. Maternity Hospital No. 3 in Tyumen performs approximately 3,000 births annually (figures for the past four years are given), which is more than 17% of the regional average (Fig. 2).

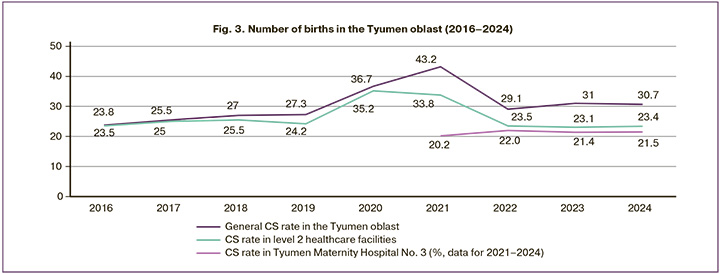

In accordance with the all-Russian trend, the CS rate in Tyumen oblast exceeds 30%. In 2024, 30.7% of the pregnant women delivered abdominally. During the pandemic, 43.2% of the patients underwent operative delivery.

In level two obstetric hospitals, the CS rate remains at the same level if we exclude the pandemic year of 2021. Maternity Hospital No. 3 in Tyumen has a lower frequency of abdominal deliveries than similar level 2 obstetric hospitals (Fig. 3).

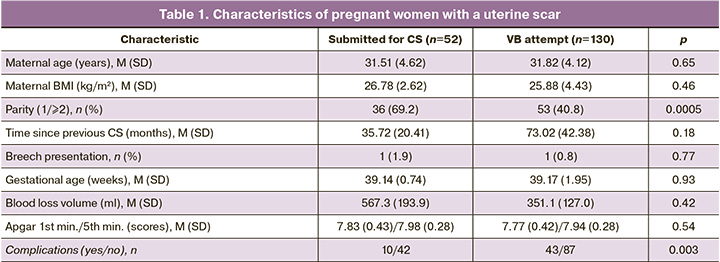

When selecting pregnant women with a uterine scar for CS, the following factors were considered: age, body mass index (BMI), number of births, time between births, fetal position, and gestational age. Labor outcome was assessed based on blood loss volume, Apgar score, complications, and infant weight.

The following reasons were used to perform operative deliveries in pregnant women with a uterine scar: refusal of the pregnant woman, 45/52 (86%); the sum of relative indications for CS, 3/52 (6%); scar failure, 3/52 (6%); and placenta accreta, 1/52 (2%). As we can see, the vast majority of refusals of vaginal birth after CS (VBAC) are due to the woman’s own decision. What are the reasons for this refusal? First, there was concern about having a healthy child due to complications such as fetal hypoxia (20/45 cases, 44.4%), weak labor (19/45 cases, 42.2%), a narrow pelvis (4/45 cases, 8.9%), and premature rupture of the membranes (2/45 cases, 4.4%). Notably, women who underwent CS had a higher BMI (Table 1).

Otherwise, these patient characteristics corresponded with those of women selected for VB after CS. A comparison of VB attempts that were successful or unsuccessful and ended in operative delivery did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the two groups of patients in terms of maternal age, BMI, time since the previous delivery, or gestational age. At the same time, the gestational age was significantly lower in cases of VB refusal than in cases of successful VB.

A statistically interesting comparison was the parity of births. Among those who had successful vaginal births, most had two or more births in their medical histories. Only 41% of pregnant women had one birth in their medical history. In the unsuccessful VB group, more than two-thirds of the births were second. In other words, there was only one birth in their history. In other words, reproductive experience is a positive prognostic factor for vaginal deliveries. The following criteria did not yield statistically significant differences: interval since previous CS, gestational age, and indications for previous CS (narrow pelvis, large fetus, breech presentation, fetal distress, gestational diabetes mellitus, and arterial hypertension).

There were no cases of maternal or neonatal mortality, uterine rupture during labor, or a neonatal Apgar score of less than seven points at 5 min in any of the VB attempts.

Ruptures occurred in 42 cases (49.4%) during VB, including seven cases (8.2%) of first-degree cervical lacerations.

Discussion

Tyumen oblast follows the global trend of an increasing incidence of CS [3, 4]. The primary burden of operative deliveries falls on the third-level obstetric hospital, the Tyumen Perinatal Center, where the CS incidence exceeds 34% and reaches 45% among women with uterine scars [20]. This is largely because perinatal centers are best equipped with human and material resources for such procedures [8]. Simultaneously, clinical guidelines in Russia permit both CS and VB for women with uterine scars in second-level obstetric hospitals [17], such as Maternity Hospital No. 3 in Tyumen, which has established appropriate conditions for women with a history of CS. The CS incidence in second-level obstetric hospitals is below the regional average, primarily due to the timely referral of pregnant women with high obstetric risks to the Perinatal Center [21]. Maternity Hospital No. 3 in Tyumen has a lower CS rate than similar second-level obstetric hospitals, attributed to extensive experience in managing deliveries for women with a uterine scar and staff readiness to facilitate VB after CS. However, compared to 2015, the CS rate has increased by nearly 7%, with the delivery of women with uterine scars contributing approximately 4.5% to this rise [8, 12, 22].

Vaginal delivery success in 65.4% of women with a uterine scar selected for VB after CS aligns with published data [14]. The absence of serious complications among women who delivered vaginally and abdominally indicates effective selection of candidates for VB, as well as timely adjustments in delivery strategy when VB is not feasible.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to develop an effective prognostic model based on the results of the observational study. The only significant indicator identified was parity: third and subsequent births were associated with a lower risk of VB in women with a uterine scar than in those with only one previous birth. Other indicators linked to successful VB after CS noted in the literature (such as age, pregestational BMI, interval between previous CSs and the current pregnancy, and estimated fetal weight) did not demonstrate a predictive value [23]. "Doubtful" indicators, particularly previous indications for CS, confirmed their lack of reliability [16]. Risk factors for unsuccessful VB attempts after CS include thickness of the lower uterine segment in the scar area of ≤2.1 mm upon admission, a Bishop score of ≤5 points indicating cervical maturation, dilation of the internal os of ≤2 cm upon admission, and early rupture of membranes [12, 16]. Future observations at Maternity Hospital No. 3 in Tyumen need to be conducted and systematically assessed.

Overall, there is a clear need for meticulous preparation for VB after CS at antenatal clinics along with individualized assessments of possible risks during the inpatient phase.

Conclusion

The study of criteria for selecting pregnant women with a uterine scar for specific types of delivery revealed a lack of information in the clinical and anamnestic indicators of the third study group, pregnant women with a scar who were not selected for VB after CS, since the primary basis for such selection was the woman's refusal of natural childbirth. When comparing patients selected for natural childbirth (both successful and unsuccessful attempts), parity emerged as a significant indicator, and in the absence of direct indications for abdominal delivery, a higher number of previous births correlated with a greater likelihood of successful VB.

Official statistics indicate that level 2 maternity hospitals are the most prevalent link in obstetric care, providing both planned and emergency medical services to pregnant women and those in labor in the Tyumen oblast. While the timely referral of women with high obstetric risks to a higher-level perinatal center is crucial, it is essential to recognize that maternity hospitals handle a significant number of births under urgent and emergency circumstances, including cases where pregnant women have not received adequate monitoring in antenatal clinics. Careful monitoring of such births will bring us closer to developing effective criteria for successful VB in women with a uterine scar. This, in turn, enhances their chances of having multiple children and contributes to addressing the demographic policy challenges.

References

- World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme, 10 April 2015. WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod. Health Matters. 2015; 23(45): 149-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2015.07.007

- Xu X.J., Jia J.X., Sang Z.Q., Li L. Association of caesarean scar defect with risk of abnormal uterine bleeding: results from meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2024; 24(1): 432. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03198-6

- Martin J.A., Hamilton B.E., Osterman M.J.K. Births in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017; (287): 1-8.

- WHO recommendations on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health 2015. World Health Organization; 2015. 86 p. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/172427/9789241508742_re?sequence=1

- Chen Y.T., Hsieh Y.C., Shen H., Cheng C.H., Lee K.H., Torng P.L. Vaginal birth after cesarean section: Experience from a regional hospital. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022; 61(3): 422-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2022.03.006

- Antoine C., Young B.K. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920-2020: the good, the bad and the ugly. J. Perinat. Med. 2020; 49(1): 5-16. https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2020-0305

- Матейкович Е.А. Качество оказания акушерско-гинекологической помощи и защита интересов врача в судебном разбирательстве. Акушерство и гинекология. 2018; 6: 92-8. [Mateikovich E.A. The quality of obstetric and gynecologic care and the protection of a physician’s interests in judicial proceedings. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; (6): 92-8. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2018.6.92-98

- Habak P.J., Kole M. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

- Grobman W.A., Sandoval G., Rice M.M., Bailit J.L., Chauhan S.P., Costantine M.M. at al. Prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in term gestations: a calculator without race and ethnicity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021; 225(6): 664.e1-664.e7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.021

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Роды одноплодные, родоразрешение путем кесарева сечения. 2024. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Singleton births, delivery by cesarean section. 2024. (in Russian)].

- Mascarello K.C., Horta B.L., Silveira M.F. Maternal complications and cesarean section without indication: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Saude Publica. 2017; 51: 105. https://dx.doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2017051000389

- Кузнецова Н.Б., Ильясова Г.М., Буштырева И.О., Гимбут В.С., Павлова Н.Г. Факторы риска влагалищных родов после кесарева сечения. Акушерство и гинекология. 2023; 10: 78-85. [Kuznetsova N.B., Ilуasova G.M., Bushtyreva I.O., Gimbut V.S., Pavlova N.G. Risk factors for vaginal delivery after cesarean section. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (10): 78-85 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.121

- Савельева Г.М., Курцер М.А., Бреслав И.Ю., Коноплянников А.Г., Латышкевич О.А. Разрывы матки в современном акушерстве. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 9: 48-55. [Savelyeva G.M., Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Konoplyannikov A.G., Latyshkevich O.A. Uterine ruptures in modern obstetrics. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (9): 48-55 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.9.48-55

- Naz S., Bano I., Rashid S., Fatima Y., Humayun P., Muzaffar T. Frequency of vaginal birth after caesarean section and its fetomaternal outcome. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2023; 35(4): 583-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.55519/JAMC-04-12015

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 205: Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019; 133(2): e110-e127. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003078

- Parveen S., Rengaraj S., Chaturvedula L. Factors associated with the outcome of TOLAC after one previous caesarean section: a retrospective cohort study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021; 42(3): 430-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2021.1916451

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Послеоперационный рубец на матке, требующий предоставления медицинской помощи матери во время беременности, родов и в послеродовом периоде. 2024. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Postoperative scar on the uterus requiring medical care for the mother during pregnancy, childbirth and in the postpartum period. 2024. (in Russian)].

- Кан Н.Е., Шмаков Р.Г., Кесова М.И., Тютюнник В.Л., Баев О.Р., Пекарев О.Г., Тетруашвили Н.К., Клименченко Н.И. Самопроизвольное родоразрешение пациенток с рубцом на матке после операции кесарева сечения. Клинический протокол. Акушерство и гинекология. 2016; 12(Приложение): 12-9. [Kan N.E., Shmakov R.G., Kesova M.I., Tyutyunnik V.L., Baev O.R., Pekarev O.G., Tetruashvili N.K., Klimenchenko N.I. Spontaneous delivery is women with a uterine scar after cesarean section. Clinical protocol. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016; 12(Suppl.): 12-9. (in Russian)].

- Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Росстат). Здравоохранение в России 2023. Статистический сборник. М.: Росстат; 2023. 179 с. [Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat). Healthcare in Russia 2023. Statistical collection. Moscow: Rosstat; 2023. 179 p. (in Russian)].

- Рудзевич А.Ю., Кукарская И.И., Хасанова В.В. Анализ частоты кесарева сечения с использованием классификации Робсона в родильных домах Тюменской области и Перинатальном центре города Тюмени. Международный журнал прикладных и фундаментальных исследований. 2021; 11: 45-9. [Rudzevich A.Yu., Kukarskaya I.I., Khasanova V.V. Analysis of the frequency of cesarean section using the Robson classification in maternity hospitals in the Tyumen region and the perinatal center in Tyumen. International Journal of Applied and Fundamental Research. 2021; 11: 45-9 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17513/mjpfi.13310

- Горев В.В., Михеева А.А. Маршрутизация беременных как один из путей снижения младенческой смертности. Здоровье мегаполиса. 2021; 2(3): 17-23. [Gorev V.V., Mikheeva A.A. Routing of pregnant women as one of the ways to reduce infant mortality. City Healthcare. 2021; 2(3): 17-23. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.47619/2713-2617.zm.2021.v2i3;17-23

- Рудзевич А.Ю., Тлашадзе Р.Р., Попкова Л.А. Анализ частоты кесарева сечения по методу Робсона в родильном доме 2-го уровня. Международный журнал прикладных и фундаментальных исследований. 2021; 8: 16-20. [Rudzevich A.Y., Tlashadze R.R., Popkova L.A. Analysis of the frequency of caesarean section according to the Robson method in the second-level hospital. International Journal of Applied and Fundamental Research. 2021; 8: 16-20. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17513/mjpfi.13256

- Вученович Ю.Д., Новикова В.А., Радзинский В.Е., Васильченко М.И., Трыкина Н.В., Старцева Н.М., Яроцкая И.А. Гистологические детерминанты попытки вагинальных родов после кесарева сечения. Акушерство и гинекология. 2022; 5: 128-39. [Vuchenovich Yu.D., Novikova V.A., Radzinsky V.E., Vasilchenko M.I., Trykina N.V., Yarotskaya I.A. Histological determinants of trial of labor after cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; (5): 128-39 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.5.128-139

Received 24.01.2025

Accepted 26.05.2025

About the Authors

Elena A. Mateykovich, PhD, Associate Professor, Director of the Institute of Maternity and Childhood, Tyumen State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 625023, Russia, Tyumen Oblast, Tyumen, Odesskaya str., 54, main building, office 310, +7(3452)69-07-58, mateykovichea@tyumsmu.ru,https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2612-7339

Irina A. Karpova, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Head of the Center of the Scientific and Clinical Center of Geostasis and Genetics of the Multidisciplinary University Clinic, Tyumen State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation,

625023, Russia, Tyumen region, Tyumen, Odesskaya str., 54, main building, 6th floor, +7(3452)69-08-00, karpovai.73@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8688-5695

Tatyana P. Shevlyukova, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tyumen State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 625002, Russia, Tyumen region, Tyumen, Daudelnaya str., 1, build. 3, 1st floor, +7(3452)69-07-58, tata21.01@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7019-6630

Inna F. Topchiu, PhD student at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tyumen State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation;

obstetrician-gynecologist, Maternity Hospital No. 3 of Tyumen, 625032, Russia, Tyumen region, Tyumen, Bauman str., 31 build. 1, +7(3452)24-94-46,

zula08061998@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3149-8660

Olga V. Bratova, Chief Physician, Maternity Hospital No. 3 of Tyumen; Teaching Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tyumen State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 625002, Russia, Tyumen Oblast, Tyumen, Daudelnaya str., 1, build. 3, 1st floor, +7(3452)24-94-46, rd3@med-to.ru

Roman N. Marchenko, Head of the Obstetrics Department, Perinatal Center (Tyumen); Teaching Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tyumen State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 625002, Russia, Tyumen Oblast, Tyumen, Daudelnaya str., 1, build. 3, 1st floor, +7(3452)69-07-58, marchenkorn@med-to.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2073-8120

Valentina A. Polyakova, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tyumen State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 625002, Russia, Tyumen Oblast, Tyumen, Daudelnaya str., 1, build. 3, 1st floor, +7(3452)69-07-58, polycova_gyn@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7008-1107