Analysis of the causes of relaparotomy after cesarean section (multicenter study)

Zharkin N.A., Miroshnikov A.E., Kostenko T.I., Shatilova A.D., Dvoryansky S.A., Dmitrieva S.L., Tskhay V.B., Raspopin Yu.S., Falkenberg M.E., Marina M.O., Artymuk N.V., Marochko T.Yu., Guseva O.I., Soboleva A.M., Panova T.V., Padrul M.M., Trushkov A.G.

Objective: To determine the characteristics of surgical strategies and methods for intra- and postoperative hemostasis in patients undergoing relaparotomy following a cesarean section.

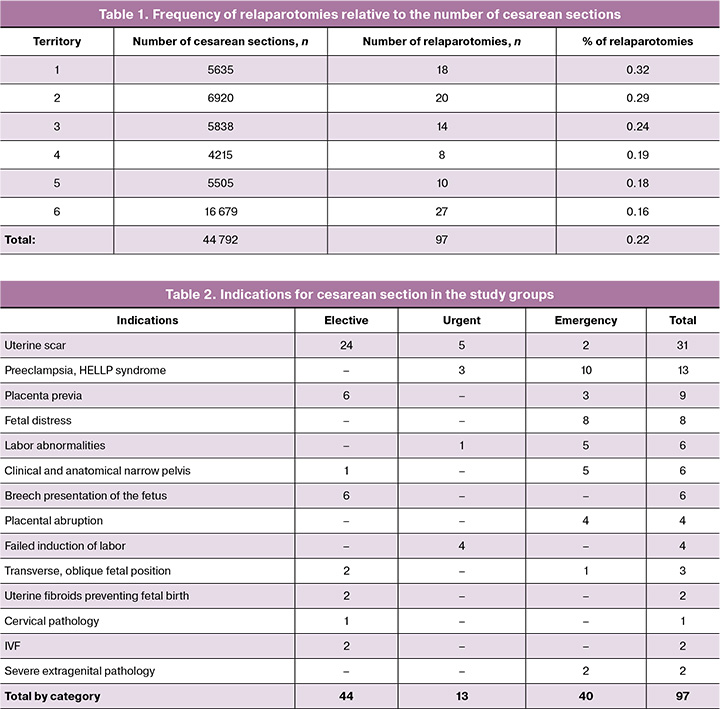

Materials and methods: A multicenter cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted to analyze the clinical and anamnestic data along with treatment outcomes of 97 cases of relaparotomy due to bleeding after cesarean section, which occurred in secondary- and tertiary-level maternity hospitals. Data were collected from six regions of the Russian Federation over three years, from January 1, 2022, to December 1, 2024: n=20, n=27, n=14, n=8, n=18, and n=10.

Results: During the analyzed three years (2022–2024), 44,792 cesarean sections were performed in institutions that reported relaparotomies. The need for surgical hemostasis during the initial operation emerged in 19/97 (19.6%) patients. Relaparotomy was performed in 97 patients, accounting for 0.22% of the total number of cesarean sections. Bleeding after cesarean section was most frequently noted at a gestational age of 37.0 (3) weeks. Relaparotomy was performed in 44 cases following planned operations, in 13 cases urgently, and in 40 cases emergently. Early postoperative bleeding (within 6 h), necessitating re-entry into the abdominal cavity, occurred in 69/97 (71.1%) parturient women. During relaparotomy, the uterus was removed as a source of bleeding in 21/97 (21.6%) cases. Ligation of the internal iliac arteries was performed in 19/97 (19.6%) patients, including five during hysterectomy and 14 while conserving the uterus. Three patients underwent repeated relaparotomy due to ongoing intra-abdominal bleeding. The mean total blood loss resulting from the two surgical interventions was 3,319 mL (1,960) ml. Blood transfusions were administered to 62 patients, of whom three received reinfusion in combination with donor erythrocytes. The mean blood transfusion volume was 1,261 (1,483) ml. The mean duration of stay in the intensive care unit was 65 (55) hours. Transfer to another institution was required in 25/97 (25.8%) postpartum women.

Conclusion: Bleeding most often occurred after planned surgery in pregnant women with uterine scars, indicating an insufficient assessment of risk factors and their prevention. Complex compression hemostasis is most frequently used to stop bleeding, which should be mastered by all surgeons performing cesarean sections.

Authors' contributions: Zharkin N.A. – conception and design of the study, drafting of the manuscript, editing of the manuscript; Miroshnikov A.E., Kostenko T.I., Dmitrieva S.L., Raspopin Yu.S., Marochko T.Yu., Soboleva A.M., Panova T.V., Trushkov A.G. – data collection and analysis; Shatilova A.D., Falkenberg M.E., Marina M.O. – statistical analysis; Artymuk N.V., Dvoryansky S.A., Tskhay V.B., Guseva O.I., Padrul M.M. – conception and design of the study, drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Volgograd State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Zharkin N.A., Miroshnikov A.E., Kostenko T.I., Shatilova A.D., Dvoryansky S.A.,

Dmitrieva S.L., Tskhay V.B., Raspopin Yu.S., Falkenberg M.E., Marina M.O., Artymuk N.V.,

Marochko T.Yu., Guseva O.I., Soboleva A.M., Panova T.V., Padrul M.M., Trushkov A.G.

Analysis of the causes of relaparotomy after cesarean section (multicenter study).

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (7): 58-66 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.102

Keywords

Obstetric hemorrhage is a persistent global challenge. Despite extensive measures implemented by WHO, FIGO, and professional societies in various countries, hemorrhage remains one of the leading causes of maternal mortality. It is believed that most cases of reproductive loss associated with postpartum hemorrhage can be prevented [1–3]. Unfortunately, as the frequency of cesarean sections has increased, so has the incidence of this problem, leading to a significant number of critical obstetric conditions [3, 4]. One adverse consequence of any abdominal surgery is relaparotomy, which is a surgical intervention performed because of complications that arise in the postoperative period [5]. According to various authors, relaparotomy after cesarean section is most frequently attributed to bleeding, with septic complications or injuries to the abdominal organs occurring much less often [6, 7]. A proposed reason for relaparotomies may be the contemporary trend towards organ-sparing operations during cesarean sections, particularly in emergency situations, which require more advanced knowledge and additional surgical skills compared to a standard cesarean section [8].

Cesarean section, especially in cases of severe preeclampsia, placental abruption, or the presence of a uterine scar, alongside uterine hypotension during surgery, are established risk factors for refractory bleeding. This type of bleeding does not respond to first-line treatments (such as uterotonic agents and tranexamic acid) and necessitates second-line therapies (including uterine balloon tamponade, administration of recombinant human factor VIIa, or uterine artery embolization) [3]. However, the potential for relaparotomy during elective surgeries, when the risk of uterine hypotension or coagulation disorders is notably high, cannot be ruled out [9, 10].

Refractory bleeding is often a reason for peripartum emergency hysterectomy, resulting in the loss of reproductive and menstrual functions [10, 11]. These considerations underscore the need for a more in-depth exploration of the issue of relaparotomy following cesarean section, as well as a discussion of the complications associated with this procedure.

This study aimed to determine the characteristics of surgical strategies and methods for intra- and postoperative hemostasis in patients undergoing relaparotomy following cesarean section.

Materials and methods

A multicenter cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted to analyze clinical and anamnestic data, as well as treatment outcomes, from 97 cases of relaparotomy for bleeding after cesarean section. The study took place over three years, from January 1, 2022, to December 1, 2024, in secondary- and tertiary-level maternity hospitals across six regions of the Russian Federation, with case distributions of n=20, n=27, n=14, n=8, n=18, and n=10. The inclusion criterion for the study was cases of relaparotomy due to bleeding after cesarean section that resulted in favorable outcomes for the patients.

The analysis was conducted according to ten criteria that characterize the volume and quality of obstetric care during the cesarean section, in the postoperative period, and during relaparotomy.

- Diagnosis and indications for cesarean section.

- Scale of the first surgery.

- Volume of blood loss during the cesarean section.

- Characteristics of the postoperative period (onset time of bleeding and volume of blood loss).

- Time interval between the first operation and relaparotomy.

- Scale of operation during relaparotomy.

- Volume of blood loss during relaparotomy.

- Duration of the patient's stay in the intensive care unit and duration of mechanical ventilation (MV).

- Blood transfusions and their volume.

- Occurrence of transfer to another hospital.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica software. For continuous variables, after checking for normality of distribution, the following were calculated: mean (M) and standard deviations (SD), medians (Me), and lower (Q1) and upper (Q3) quartiles. Data are presented as M (SD) and Me (Q1; Q3). Categorical data are presented as counts and percentages.

Results and discussion

Over the three years analyzed (2022–2024), 44,792 cesarean sections were performed in institutions that provided information on relaparotomies. Relaparotomy was performed in 97 cases, accounting for 0.22% of cesarean sections (Table 1).

The mean age of the patients was 32.1 (5.8) years. One-third of the women had a history of abortion (pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy (n=2), miscarriage (n=8). The current pregnancy occurred naturally in 91 women by in vitro fertilization (IVF) in 6. The percentage of primiparous women was 26/97 (26.8%), multiparous women – 71/97 (73.2%).

Half of the patients had somatic pathology, which could have influenced complications in the postoperative period in one way or another: iron deficiency anemia in 16/97 (16.5%), obesity in 16/97 (16.5%), type 2 diabetes mellitus in 2/97 (2.1%), thyroid pathology in 7/97 (7.2%), hypertensive disease in 6/97 (6.2%), inflammatory diseases of the urogenital tract (cystitis, pyelonephritis, vulvovaginitis) in 9/97 (9.3%), varicose veins in 5/97 (5.2%), and others (nicotine addiction, dorsopathy, etc.) in 9/97 (9.3%).

This pregnancy was complicated by preeclampsia in 10 patients, placenta previa in 9, amniotic fluid embolism in 1, oligohydramnios in 4, transverse fetal position in 4, acute thrombosis of the femoral vein in 1, and placental abruption in 5. Multiple pregnancies occurred in 10 patients, including two triplets. Pregnancy occurred as a result of the use of assisted reproductive technologies in six women.

Cesarean section was performed for the first time in 53/97 (54.6%) pregnant women; a uterine scar after cesarean section was present in 44/97 (45.4%) women, of which after one operation in 22 patients, after two in 15, and after three or more in 7. Indications for the previous cesarean section, when it was performed for the first time, were: premature rupture of membranes and absence of labor − 10 (22.7%), uncorrectable disorders of labor − 4 (9.1%), progressive fetal hypoxia − 4 (9.1%), anatomical or clinical narrow pelvis − 4 (9.1%), severe preeclampsia − 2 (4.5%), breech and transverse fetal position − 2 (4.5%), progressive placental abruption − 1 (2.3%), symphysiopathy − 1 (2.3%).

Indications for cesarean section during this pregnancy were planned in 44 pregnant women, urgent in 13, and emergency in 40 [11] (Table 2).

It should be emphasized that most of the operations were performed on a planned basis; that is, the risk of probable complications was assessed, but preventive measures of tactical or technical nature were either not applied or were insufficient. In an urgent manner, surgeries were most often performed for indications that arose during childbirth: lack of effect from labor induction, moderate preeclampsia in combination with other factors, and uterine scar failure. Among the emergency indications, the predominance of critical obstetric conditions, accompanied by a hypotonic state of the uterus and massive blood loss, fetal distress, as well as life-threatening conditions in extra-genital pathology, has attracted attention. In this category, 15/40 patients had severe preeclampsia (8), total placental abruption (3), HELLP syndrome (3), and acute femoral vein thrombosis (1).

Most cesarean sections were performed at term – 37.3 (3.0) weeks, premature operative deliveries occurred in 28/97 (28.9%) pregnant women, and the minimum gestational age in one case was 25 weeks of gestation. No postpartum pregnancy was observed. Twin pregnancy was observed in 8 women, including one after IVF. There were two triplets, one after the IVF.

A transverse suprapubic incision of the anterior abdominal wall was made in 90 patients, and a lower midline laparotomy was performed in 7/97 (7.2%). A longitudinal incision was chosen because of placenta previa and its abnormal placentation in four women with a history of cesarean section due to scar failure after cesarean section and the chances of hysterectomy – in two and only in one case – in a primiparous woman due to a clinically narrow pelvis and a large fetus. A cesarean section with a transverse incision in the lower segment of the uterus was performed in 95/97 (97.9%) patients. Fundal cesarean section was performed in 2 pregnant women with placenta previa.

The usual scale of the operation (cesarean section only) was performed in half (49/97) of the patients; in the remaining cases, the scale of the operation was expanded. Metroplasty due to the presence of a scar on the uterus was performed in 17/44 (38.6%) patients, including excision of a placental hernia in 1 patient and sterilization in 11/97 (11.3%) patients. In two cases, the uterus was removed because of total placental abruption, Couvelaire uterus (in one case), and complete placenta previa (in one case). In one case, the scale of the operation was expanded due to myomectomy, and in 1 case, a simultaneous operation, appendectomy, was performed.

The need for additional hemostasis during the first operation was observed in 19/97 (19.6%) cases. The reasons for this were the hypotonic state of the uterus in 17 patients, trauma to the myometrium, and vascular bundles of the uterus in 2. Placental ingrowth was detected in two cases; hysterectomy was performed in one case with ingrowth of placenta previa. One additional method of hemostasis was used in eight cases and a combination of several methods was used in 11 cases. Most often, uterine devascularization was performed – in 13 and the application of compression sutures – in 11 according to various methods (B-Linch, Pereyra, Cho, Hayman). Less often, controlled balloon tamponade (UBT) of the postpartum uterus was performed in 6 cases, and a temporary tourniquet was applied to the lower segment of the uterus. A blood reinfusion device was used in only one case.

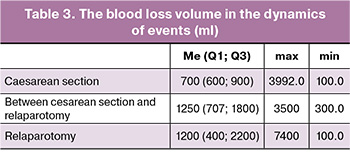

On average, the volume of blood loss during cesarean section did not exceed the criterion of massive; however, in cases related to critical obstetric conditions, it was greater. Thus, a blood loss of 1500 ml or more was observed in 12 cases, from 1000 to 1499 ml – in 10, 600 to 999 ml – in 55, and less than 600 ml – in 20 cases. Thus, in 75/97 (77.3%) women, the volume of blood loss during cesarean section was less than 1000 ml and did not portend a catastrophe that served as a reason for relaparotomy.

An important criterion for analyzing the complicated course of the postoperative period is the time from the moment the operation is completed to the onset of bleeding. There was a clear predisposition to the early manifestation of postoperative complications [Me=2.83 (1.91; 11.9) h, min=0.08 h; max=48 h], which also determined the moment of the decision to start relaparotomy [Me=3.2 (1.74; 36.24) h, min=0.08 h; max=120 h]. Within the first hour after the completion of the cesarean section, the decision to perform relaparotomy was made in 10 patients, and in 3 cases, it was immediately after the sutures were applied to the skin. This circumstance indicates an excessive haste in completing the operation and underestimating the risk factors that were realized immediately. In the interval from 1 to 6 h postoperatively, relaparotomy was performed in the of 59/97 (60.8%) patients. Thus, two-thirds of the mothers (69/97) had an early manifestation of postoperative bleeding that required repeated access to the abdominal cavity. Later than 24 h after the postoperative period, 9/97 (9.2%) mothers underwent reoperation.

The volume of blood loss during the postoperative period varied from insignificant to massive. Blood loss in the interval from 1000 to 2000 ml occurred in eight mothers, over 2000 ml – in five. All of these patients showed an early manifestation of postoperative complications, which was an indication for emergency relaparotomy during the first hours after cesarean section. The formulations of the diagnoses that were in the history of childbirth were of a diverse nature but were reduced to one: obstetric bleeding. The most threatening complications were life-threatening massive bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, early postpartum bleeding, hypo-atonic bleeding, intra-abdominal bleeding, and ongoing bleeding.

In the late postpartum period, the indications for relaparotomy were hematomas of various localizations, detected using echography: suture on the uterus in five, parametria in three, interligamentous space in two, aponeurosis in eight, prevesical tissue in two, and subcutaneous tissue – in 1. In 3 cases, hematomas were combined. There was no external bleeding after cesarean section in these patients; however, there were symptoms of increasing anemia, in connection with which they underwent revision of the abdominal organs with additional hemostasis. In two cases (25 and 48 h after cesarean section), total hysterectomy without appendages was performed because of coagulopathic bleeding.

It is quite obvious that repeated surgical intervention in the postpartum period is accompanied by additional blood loss and exacerbates the condition of patients (Table 3).

The data presented in the table indicate that in the postpartum period and during the performance of relaparotomy, the volumes of blood loss were massive, indicating an exacerbation of the acute anemic condition. The total volume of blood loss per case of cesarean section with a complicated course in the postoperative period, which ended with relaparotomy, was 2780 (1850; 4700) ml. Despite these circumstances, there were no indications for the use of thromboelastography during cesarean section or during laparotomy in any history of childbirth.

The final stopping of bleeding during relaparotomy was achieved in various ways. The uterus was removed as a source of bleeding in 21/97 (21.6%) cases. Ligation of the internal iliac arteries was performed in 19/97 (19.6%) patients, including hysterectomy in 5 patients and preservation of the uterus in 14 patients. Complex compression hemostasis in the form of ligation of the ascending branches of the uterine arteries and compression sutures (most often in the Pereyra modification) was performed in 62/97 (63.9%) patients. Of these, in one case, additional compression of the uterus with an elastic bandage was performed, and in two cases, a balloon catheter was inserted into the uterus intraoperatively for UBT in the postoperative period. Additional local hemostasis was required in only 3 parturient women. In two patients, repeated relaparotomy and additional hemostasis by ligation of the internal iliac arteries were performed due to ongoing intra-abdominal bleeding. In one case, during repeated relaparotomy, it was possible to preserve the uterus, limiting it to revision of the abdominal organs and its drainage; in the other case, the operation ended with hysterectomy. Thus, in the studied group of parturients, hysterectomy was performed in 23/97 (23.7%) cases.

Hemotransfusion was performed in 62 patients, two of whom received reinfusion in combination with donor erythrocytes and one received transfusion of only her own blood. The average blood transfusion volume was 1000 ml (Me=946 [634; 1165] ml, min=400 ml, max=4170 ml). In accordance with the current trend of limiting the duration of mechanical ventilation owing to the risk of severe pneumonia, the average duration of mechanical ventilation was 13 (min 1; max 120) hours. Mechanical ventilation was required in 40/97 of the (41.2%) patients. The length of stay in the intensive care unit is an important indicator of the patient's severity and material costs, as they are several times greater than those in the somatic ward. In the studied group of women in labor, it exceeded one day [Me=48 (30; 72) h].

Transfer to another facility was required by 25/97 (25.8%) women in labor, of which 6 were transferred to the gynecology department, 5 to the surgical department (surgery, urology), and 14 to a higher-level facility. The duration of hospitalization after relaparotomy averaged 7.7 (4.2) days. Expert analysis of relaparotomy after cesarean section revealed tactical errors in all patients. The general shortcoming should include underestimation of the risk of postpartum hemorrhage during cesarean section due to high parity, the presence of chronic extragenital pathology (anemia, chronic infectious diseases), a scar on the uterus, multiple pregnancies, and severe pregnancy complications in the form of preeclampsia, premature birth, placenta previa, and premature detachment of normally and low-lying placenta. Underestimation of the risk of bleeding was evidenced by the usual volume of cesarean section in half of the group. This should be particularly remembered when several of the listed factors are combined. In such cases, it is advisable to carry out additional measures to prevent bleeding using various methods of uterine devascularization, without waiting for intraoperative blood loss to become massive, as well as when the contractility of the uterus is questionable (unstable). First, it concerns situations with abnormal placental attachment or overstretching of the uterus. A wider use of UBT in the postoperative period for prophylactic purposes could have prevented this catastrophe. In our opinion, another tactical error was the insufficient volume of surgery during cesarean section in every fifth pregnant woman when additional hemostasis was performed, which turned out to be ineffective. Apparently, these are cases that, during relaparotomy, ended in extirpation of the uterus, which probably should have been performed during the first operation. An important omission in these situations is the lack of determination of the coagulation capacity of blood in the operating room using a thromboelastogram [12].

In addition to intensive therapy for impaired blood coagulation, additional surgical procedures are necessary to reduce the blood flow to the uterus and restore contractility. These procedures may include devascularization, external compression of the uterus, or a combination of these methods [13]. If attempts to stop bleeding fail, hysterectomy is the only option to prevent maternal mortality.

A significant drawback of performing planned and sometimes emergency surgeries in patients with a high risk of uterine bleeding is the inability to utilize modern blood-saving technologies such as blood reinfusion. In these cases, devascularization of the uterus may not suffice to minimize blood loss, as it is typically performed after the extraction of the fetus and placenta when bleeding has already commenced.

Technical errors included trauma to the myometrium and vascular bundles of the uterine artery in two cases, indicating an incorrect choice of incision site on the uterus or removal of the fetal head into the wound.

Summary

- The average frequency of relaparotomies due to bleeding was two cases per 1,000 cesarean sections.

- Most postoperative bleeding requiring relaparotomy occurred after planned operations in pregnant women with a uterine scar and much less frequently in emergency cases due to severe preeclampsia and complicated labor.

- Probable causes of postoperative bleeding included tactical errors stemming from an underestimation of the risk of complications, particularly when multiple significant factors negatively affected uterine tone and blood coagulation properties, such as obstetric complications, alongside extragenital pathology.

- Underestimating the risk of postoperative complications led to insufficient volume of the initial operation, which could have been expanded through prophylactic devascularization of the uterus or hysterectomy when preserving the organ was questionable. In this study, organ-removing surgery was performed in 23 of 97 (23.7%) patients, with only two cases occurring during the first operation.

- An important factor contributing to bleeding after cesarean sections in high-risk pregnant women was the lack of perioperative support, particularly the absence of blood reinfusion and thromboelastography in cases of massive blood loss during the first operation.

- In the presented cases of relaparotomy, well-known methods of complex compression hemostasis were most frequently employed to finally stop the bleeding: ligation of the uterine arteries at two levels in combination with various modifications of compression sutures were used in 62 out of 97 (63.9%) patients. This highlights the need for all surgeons performing cesarean sections to master these simple and accessible methods, encouraging their more frequent use for prophylactic purposes.

Conclusion

The descriptive nature of the study, lack of a unified protocol for assessing critical obstetric conditions and their consequences, and variations in surgical tactics and techniques across different regions and maternity institutions limited the results obtained. However, these findings underscore the need for a more thorough assessment of the risk of postoperative bleeding, considering anamnestic information and obstetric and somatic status. This approach will facilitate the implementation of measures to prevent such complications. The results may serve as a foundation for incorporating preventive strategies into clinical guidelines for cesarean sections.

References

- Всемирная организация здравоохранения. Рекомендации ВОЗ по профилактике и лечению послеродового кровотечения. Женева: ВОЗ; 2014. 41 с. [World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva: WHO; 2014. 41 p. (in Russian)].

- Andrikopoulou M., D'Alton M.E. Postpartum hemorrhage: early identification challenges. Semin. Perinatol. 2019; 43(1): 11-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2018.11.003

- Артымук Н.В., Белокриницкая Т.Е. Кровотечения в акушерской практике. Руководство для врачей. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2024. 232 с. [Artymuk N.V., Belokrinitskaya T.E. Bleeding in obstetric practice. A guide for doctors. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2024. 232 p. (in Russian)].

- Белоцерковцева Л.Д., Иванников С.Е., Мирзозода М.Т. Аудит случаев релапаротомии после родов. Вестник СурГУ. Медицина. 2019; 2(40): 50-6. [Belotserkovtseva L.D., Ivannikov S.E., Mirzozoda M.T. Cases audit of relaparotomy after delivery. Bulletin of Surgut State University. Medicine. 2019; 2(40): 50-6 (in Russian)].

- Akkurt M.O., Coşkun B., Guclu T., Cift T., Korkmazer E. Risk factors for relaparotomy after cesarean delivery and related maternal near-miss event due to bleeding. J. Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2018; 33(10): 1-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2018.1527309

- Курбонов Ш.М., Курбонов К.М., Ахмедова З.Б. Акушерские кровотечения после кесарева сечения и методы их лечения: состояние проблемы и перспективы. Вестник последипломного образования в сфере здравоохранения. 2020; 4: 83-91. [Kurbonov Sh.M., Kurbonov K.M., Akhmedova Z.B. Obstetric bleeding after cesarean section and their treatment methods: the problem state and prospects. Bulletin of postgraduate education in health care. 2020; 4: 83-91 (in Russian)].

- Liu L.Y., Nathan L., Sheen J.J., Goffman D. Review of current insights and therapeutic approaches for the treatment of refractory postpartum hemorrhage. Int. J. Womens Health. 2023; 15: 905-26. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S366675

- Huras H., Radon-Pokracka M., Nowak M. Relaparotomy following cesarean section − a single center study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018; 225: 185-88. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.04.034

- Курбонов Ш.М. Анализ клинико-анамнестических данных пациенток, перенесших релапаротомию и повторные миниинвазивные вмешательства после акушерско-гинекологических операций. Медицинский вестник Национальной академии наук Таджикистана. 2021; 11(1): 21-8. [Kurbonov Sh.M. Clinical and anamnestic data analysis of patients who underwent relaparotomy and repeated minimally invasive interventions after obstetric and gynecological surgeries. Medical Bulletin of the National Academy of Sciences of Tajikistan. 2021; 11(1): 21-8 (in Russian)].

- Артымук Н.В., Марочко Т.Ю., Артымук Д.А., Апресян С.В., Колесникова Н.Б., Аталян А.В., Шибельгут Н.М., Батина Н.А. Факторы риска и протективные факторы рефрактерного послеродового кровотечения. Акушерство и гинекология. 2024; 10: 82-90. [Artymuk N.V., Marochko T.Yu., Artymuk D.A., Apresyan S.V., Kolesnikova N.B., Atalyan A.V., Shibelgut N.M., Batina N.A. Risk factors and protective factors of refractory postpartum hemorrhage. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024; (10): 82-90 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.169

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Роды одноплодные, родоразрешение путем кесарева сечения. М.; 2021. 44 c. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Singleton birth. Delivery by cesarean section. Moscow; 2021. 44 p. (in Russian)].

- Баринов С.В. Медянникова И.В., Тирская Ю.И., Безнощенко Г.Б., Кадцына Т.В., Лазарева О.В., Чуловский Ю.И., Проданчук Е.Г., Цыганкова О.Ю., Галянская Е.Г. Тромбоэластография в акушерской практике. Вопросы гинекологии, акушерства и перинатологии. 2022; 21(2): 63-8. [Barinov S.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Beznoshchenko G.B., Kadtsyna T.V., Lazareva O.V., Chulovsky Yu.I., Prodanchuk E.G., Tsygankova O.Yu., Galyanskaya E.G. Thromboelastography in obstetric practice. Gynecology, Obstetrics and Perinatology. 2022; 21(2): 63-8 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.20953/1726-1678-2022-2-63-68

- Жаркин Н.А., Бурова Н.А., Мирошников А.Е., Шатилова Ю.А. Интраоперационный гемостаз при преждевременном отделении нормально расположенной плаценты – право выбора. Доктор.Ру. 2024; 23(5): 37-42. [Zharkin N.A., Burova N.A., Miroshnikov A.E., Shatilova Yu.A. Intraoperative hemostasis with placenta abruption — the right choice. Doctor.Ru. 2024; 23(5): 37-42 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.31550/1727-2378-2024-23-5-37-42

Received 11.04.2025

Accepted 18.06.2025

About the Authors

Nikolay A. Zharkin, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Volgograd State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,400066, Russia, Volgograd, Pavshikh Bortsov sqr., 1, +7(8442)38-50-05, zharkin55@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8094-0427

Anatoly E. Miroshnikov, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Volgograd State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

400066, Russia, Volgograd, Pavshikh Bortsov sqr., 1, +7(8442)38-50-05, miroshnikov-7@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3731-0825

Tatyana I. Kostenko, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Institute for Continuing Medical and Pharmaceutical Education,

Volgograd State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 400066, Russia, Volgograd, Pavshikh Bortsov sqr., 1, +7(8442)38-50-05, kostenko.ti@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5203-3400

Anastasia D. Shatilova, 5th year student, Volgograd State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 400066, Russia, Volgograd, Pavshikh Bortsov sqr., 1,

+7(8442)38-50-05, juliashatilova2012@yandex.ru

Natalya V. Artymuk, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology named after Prof. G.A. Ushakova, Kemerovo State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 650056, Russia, Kemerovo, Voroshilova str., 22a, +7(3842)73-48-56, artymuk@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7014-6492

Tatyana Yu. Marochko, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology named after Prof. G.A. Ushakova, Kemerovo State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 650060, Russia, Kemerovo, Voroshilova str., 22a, +7(3842)73-48-56, marochko.2006.68@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5641-5246

Sergey A. Dvoryansky, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kirov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

610998, Russia, Kirov, К. Мarks str., 112, +7(8332)64-09-76, dvorsa@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5632-0447

Svetlana L. Dmitrieva, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kirov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

610998, Russia, Kirov, К. Мarks str., 112, +7(8332)64-09-76, swdmitr09@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2505-0202

Vitaly B. Tskhay, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Perinatology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Prof. V.F. Voyno-Yasenetsky Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 660022, Russia, Krasnoyarsk, Partizana Zheleznyaka str., 1, +7(923)287-21-34, tchai@yandex.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2228-3884

Yuri S. Raspopin, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation of the Institute for Postgraduate Education, Prof. V.F. Voyno-Yasenetsky Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 660022, Russia, Krasnoyarsk, Partizana Zheleznyaka str., 1; Head of the Department of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation, Krasnoyarsk Central Clinical Hospital, +7(950)413-87-48, oar24@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5550-1628

Maria E. Falkenberg, student at the General Medicine Faculty, Prof. V.F. Voyno-Yasenetsky Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

660022, Russia, Krasnoyarsk, Partizana Zheleznyaka str., 1, +7(902)980-56-14, mariafalkenberg@yandex.ru

Marina O. Marina, student at the General Medicine Faculty, Prof. V.F. Voyno-Yasenetsky Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

660022, Russia, Krasnoyarsk, Partizana Zheleznyaka str., 1, +7(953)596-58-79, marina.veter2016@yandex.ru

Olga I. Guseva, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Faculty of Continuing Professional Education, Volga Region Research Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 603005, Russia, Nizhny Novgorod, Minin and Pozharsky sqr., 10/1, +7(831)422-20-00, alise52@yandex.ru,

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-1241-7076

Anna M. Soboleva, resident, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Faculty of Continuing Professional Education, Volga Region Research Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, 603005, Russia, Nizhny Novgorod, Minin and Pozharsky sqr., 10/1, +7(8312)281-05-52, anna.sofonova@yandex.ru

Tatyana V. Panova, PhD, Head of the Department of Maternal Pathology No. 5, Regional Perinatal Center of the City Clinical Hospital No. 40,

603083, Russia, Nizhny Novgorod, Hero Yuri Smirnov str., 71, bld. 5, +7(8312)281-05-52, tatvpanova@yandex.ru

Mikhail M. Padrul, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 1, Academician E.A. Wagner Perm State Medical University,

Ministry of Health of Russia, 614000, Russia, Perm, Petropavlovskaya str., 26, +7(342)217-21-20, psmu@psma.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6111-5093

Andrey G. Trushkov, PhD, Deputy Chief Physician for Obstetrics and Gynecology, City Clinical Hospital named after M.A. Tverje, 614036, Russia, Perm,

Bratyev Ignatovykh str., 2, +7(342)207-09-01, trushkovi@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6068-8436

Corresponding author: Anatoly E. Miroshnikov, miroshnikov-7@mail.ru