Respectful midwifery care

Mazúchová L., Porubská A., Kelčíková S., Maskalová E., Malinovská N.

Introduction: Obstetric care that respects a woman’s autonomy during childbirth is a basic component of quality care that every woman needs and deserves during childbirth.

Objective: To determine the degree of respect for a woman’s autonomy during childbirth and providing respectful care as well as their interrelationship.

Materials and methods: A quantitative cross-sectional study design was chosen. The study sample included 453 women (mean age is 29.8 (4.6) years) after spontaneous vaginal delivery from 0 to 1 year. The tool for data collection was the MADM questionnaire supplemented with self-constructed questions. Descriptive and inductive statistics (Student’s t-test) were used for analysis.

Results: The mean MADM scale score was 24.9 (10.33) which represents the borderline between the low and adequate degrees of parturient woman’s autonomy. In the assessment of respectful care, the lowest scores were obtained for questions related to the possibility of choosing a position, the woman’s feeling that she could refuse any routine procedure or examination, and the possibility of moving freely in the delivery room. A statistically significant association was demonstrated between the degree of women’s autonomy during childbirth and all variables of respectful care.

Conclusion: Health care providers should make every effort to actively support a woman’s autonomy during childbirth in all available ways to ensure that respectful care becomes the norm.

Authors’ contributions: Mazúchová L., Porubská A. – developing the concept and design of the study, collecting and processing the material; Porubská A., Mazúchová L. – statistical processing of the data; Mazúchová L., Malinovská N., Kelčíková S., Maskálová E. – writing the text; Malinovská N. – editing the article.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financing: There was no funding obtained for the study.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board “Ethics of the Žilina and Trnava self-governing regions”.

Patient Consent Publication: The patients provided an informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Mazúchová L., Porubská A., Kelčíková S., Maskalová E., Malinovská N. Respectful midwifery care.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024; (11): 110-117 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.213

Keywords

One of the fundamental principles of healthcare is respect for the human being as an autonomous entity with his or her own inherent needs and desires. Autonomy can be understood as a person՚s ability to act freely and independently. Trust is essential in the relationship between a patient and a healthcare provider (woman in labour and a healthcare provider). Although both the provider and the woman have the same goal, namely to deliver a healthy baby during a successful uncomplicated labour, their positions and the overall situation are very different. If the healthcare provider is in his or her home environment, he or she is a professional and wants to do the job well, the woman is in a completely different situation: she is under the influence of the hormonal processes associated with childbirth, under the influence of pain, fear, and expectations; but what is more important that the woman faces a completely unique event that can give her a sense of fulfilment and empowerment in her new role as a mother, or on the contrary, lead to deep disappointment, frustration and even traumatic experiences.

Respect for the autonomy of the woman in labour is a key factor in obstetric care [1, 2]. It implies respect for the integrity of the client՚s values, her beliefs, her views regarding her interests and the use of only those clinical strategies that can be implemented with her consent on the basis of informed choice.

The biomedical model, which is still widely used today, cannot eliminate some negative phenomena (such as lack of personalised, continuous and woman-centred care, excessive medical interventions in low-risk pregnancies, etc.) [3].

The process of childbirth is currently undergoing a transformation, which may be described as the humanisation of childbirth. This term refers to understanding that a woman in labour is a human being and the process of labor should bring satisfaction and empowerment to women and their caregivers; such values as women՚s emotional state, attitudes, beliefs, sense of dignity and autonomy during childbirth should be taken into account. The woman assumes a central role in the labour process and in decision-making [4].

Respectful maternity care (RMC) can now be described as care that preserves dignity, privacy and confidentiality, ensures protection from harm and abuse, and provides shared decision-making (SDM) and ongoing support during labor [5, 6].

The objective of the study is to determine the degree of respect for women’s autonomy during childbirth and providing respectful care as well as their interrelationship.

Materials and methods

The study design is a cross-sectional quantitative study.

Study participants

The study sample consisted of 453 women, with a mean age of 29.8 (4.6) years. The female respondents were chosen intentionally. The women were enrolled in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: the period after spontaneous vaginal delivery is from 0 to 1 year, signed informed consent for inclusion in the study. The study sample consisted of 234/453 (51.7%) women with higher education, 213/453 (47.0%) with secondary education and 6/453 (1.3%) with primary education. Most respondents, namely, 245/453 (54.1%) were primiparous; 208/453 (45.9%) were multiparous.

Study methods

A questionnaire was used to collect the data. In the introduction, there were identifying points that were necessary to characterize the study sample. The standardized questionnaire MADM (The Mother’s Autonomy in Decision Making scale) was used. It is a valid and reliable tool for assessing women’s autonomy and autonomous decision-making during childbirth [7]. The questionnaire contained 7 questions. The responses were rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). According to the MADM questionnaire, a lower score is indicative of a lower level of autonomy. The minimum possible score of 7 and the maximum achievable score of 42 indicate that women are more empowered to take an active role in labor and decision-making processes.

The questionnaire was supplemented with 12 self-administered statements related to respectful care towards women in labor by healthcare providers. The degree of agreement was rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

Organization of the study

The data were collected between February and December 2020. The questionnaire was distributed in outpatient clinics for children and adolescents. The questionnaire was completed on-site by women who had provided their consent and supplied an email address where the questionnaire was sent. The questionnaire could be completed in writing or electronically. The cumulative return of questionnaires was 460 out of 520 (88.5%). A total of 460 questionnaires were analyzed; however, seven were excluded due to incorrect or incomplete responses, or failure to meet the inclusion criteria. As a result, the total number of questionnaires included in the study was 453.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board “Ethics of the Žilina and Trnava self-governing regions”.

Statistical analysis

The statistical processing of the data was conducted using Microsoft Office Excel and PSPP statistical software. The methods of descriptive statistics were used to obtain the results of statistical processing. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (Z=1.22; p≤0.083) was used to determine the normality of the data distribution, which was consistent with a normal distribution, i.e. parametric distribution of the data. Student’s t-test was used to obtain statistical significance of differences between groups of respondents.

Results

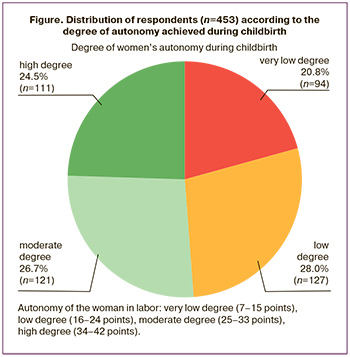

The quantitative assessment of women’s autonomy during labor evaluated according to the MADM questionnaire is presented in Figure 1.

Most of the women (127/453 (28.04%)) reported a low degree of autonomy during labor. The degree of autonomy was rated as moderate by 121/453 (26.71%) and as high by 111/453 (24.50%) female respondents. The least number of women (94/453 (20.75%)) indicated a very low degree of autonomy.

The mean MADM score was 24.9 (10.3) and the median value was 25. The above values define the boundary between a low and adequate degree of autonomy of the woman in labor.

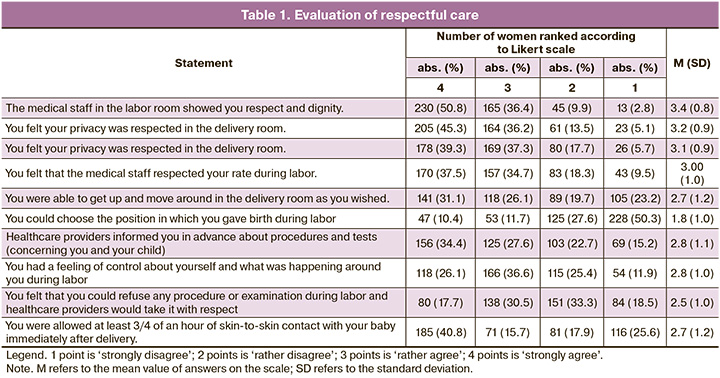

The evaluation of respectful care is presented in Table 1.

According to the mean value of the Likert scale, the lowest score (the worst score) was given to the statement about the possibility of choosing the position in which the woman gave birth. A total of 353/453 (77.9%) of the female respondents expressed disagreement. It should be emphasized that most women (235/453 (51.9%)) disagreed with the statement ‘You felt that you could refuse any procedure or examination during labor and healthcare providers would take it with respect’.

The statement with the lowest score was about freedom of movement in the delivery room. A total of 194/453 (42.8%) of the female participants expressed disagreement. In contrast, the most highly rated statement was that health workers showed respect and honor to the women; 395/453 (87.2%) female respondents confirmed this positive experience. A total of 369/453 (81.5%) and 347/453 (76.6%) women expressed agreement with the statements related to respect for privacy and intimacy, respectively.

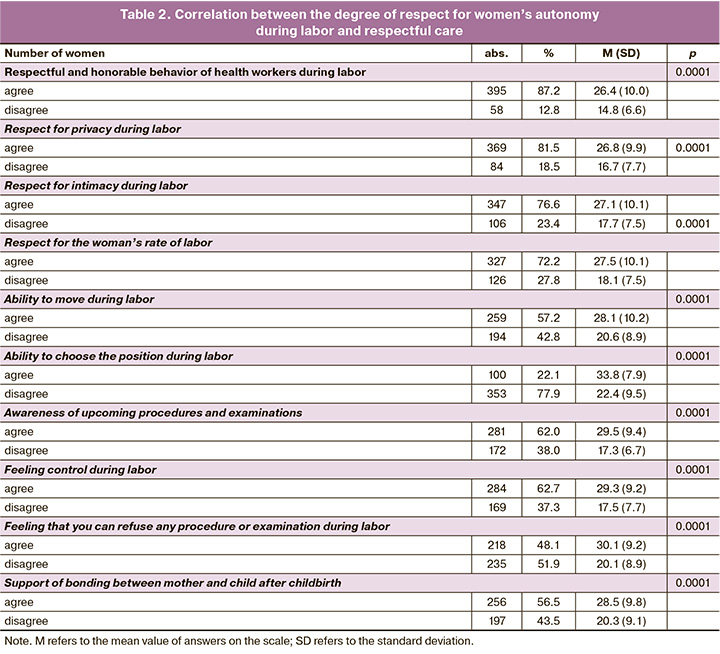

The use of Student’s t-test revealed statistically significant differences between the degree of autonomy of the woman during childbirth and the behavior of health workers (Table 2), expressed in respect and honor to the woman (p<0.0001), respect for her privacy (p<0.0001), respect for her intimacy (p<0.0001) and respect for her own rate of labor (p<0.0001), ability to move during labor (p<0.0001), ability to choose her position during labor (p<0.0001), awareness of upcoming procedures and examinations (p<0.0001), feeling control during labor (p<0.0001), ability to refuse any procedure or examination during labor (p<0001) and support of bonding after childbirth (p<0.0001).

Discussion

We investigated the level of respect for women’s autonomy by healthcare providers during labor. In our study, approximately 51% of women demonstrated a high and sufficient degree of autonomy, while almost 49% showed a low or very low degree of autonomy during labor (Figure 1). We found lower respect for women’s autonomy during labor compared to a study conducted in the Netherlands (n=557) where 84% of women achieved a satisfactory to high degree of autonomy, while only 16% of women achieved a low or very low degree of autonomy. The mean MADM score obtained in our study group was 24.9 (10.3). These numbers range from low degree of autonomy to sufficient degree of autonomy. The obtained results were again more unfavorable compared to the study conducted by Vedam S. et al. [8], where the median initial score of the MADM questionnaire was 39, indicating a higher degree of women’s autonomy.

We conducted a study of respectful care given by healthcare providers to women during labor. In particular, the investigation focused on the manifestation of respectful care in the behavior of healthcare providers. Iravani M. et al. found that an important aspect of care for women during childbirth is respect, reverence and trust [9]. In terms of these manifestations from healthcare providers, the majority of female respondents reported positive experiences, whereas almost 13% of women reported negative experiences (Table 1). Positive communication and interaction during childbirth (respect, reverence) significantly affect the woman’s experience, which in turn can influence her mental and physical health, as well as her relationship with her child after birth [10].

According to a systematic review, positive communication demonstrating reverence and respect reduces the incidence of cesarean section, operative vaginal delivery, use of anesthesia, and negative feelings about the birth experience [11].

This study examined the manifestation of respectful care in the protection of privacy and intimacy. The majority of female respondents in the study stated that their privacy and intimate life were respected. Confidentiality was not respected in 19% of women and intimacy was not respected in 23.4% of women. Similar results were obtained in another study conducted by Slovakian scientists [12]. If the care is mother-centered, healthcare providers must create and maintain an atmosphere characterized by intimacy and confidentiality. There are four types of confidentiality: physical, social, informational, and psychological.

The present study examined the respectful approach of healthcare providers to women based on three factors: their natural rate of labor, their ability to move around in the delivery room, and their choice of delivery position. In our study, 27.8% of women reported that health care providers did not consider their own rate of labor, almost 43% of women could not move freely in the delivery room during labor, and only 22.1% could choose the position in which they gave birth (Table 1). These results are comparable to those of another study performed in Slovakia [13]. Afulani P.A. et al. found that 38% of women in labor did not have the opportunity to try different positions and choose the one that suited them best for labor [14]. Despite the fact that these are the main international recommendations for care during labor, there is still a striking contrast between the recommendations and daily practice [15].

There was an investigation of the respectful approach of healthcare providers to women in terms of information, a sense of control, and the ability to refuse routine procedures or examinations during labor. Supportive care during labor includes emotional support, detailed information to the woman in labor, respect for refusal of proposed procedures, which can increase the feeling of control over one’s own body and the process of labor, and a sense of greater competence. All these factors can ultimately promote the physiological processes of labor and reduce unnecessary interventions [16]. In our study, more than half of the respondents were satisfied with early information about upcoming procedures or examinations, but almost 38% of women said they were not sufficiently informed in advance (Table 1). These results are comparable to those reported in a study by Afulani P.A. et al. [14], where 33% of women reported a lack of awareness. Regarding the feeling of control over one’s own body and the process of labor, 37.3% of women gave negative assessments (Table 1), which are comparable with the study conducted in Slovakia [13]. The study conducted by Reis T.L.R.D et al. showed the importance of the health care provider’s approach to the woman in labor and her control of the birth process [15]. When an authoritarian approach is taken, the woman automatically loses control over her own body and the process of childbirth. The affective component of control, that is, the “feeling” of being influential and having a say in what happens, and the presence of healthcare providers who are responsive to her wishes, appears to be of greater importance to women than the concept of “having control” [17]. The issue of refusing a procedure or examination during childbirth when treated respectfully by healthcare providers was rated negatively by more than half of the respondents. Less than half of the women reported that they felt their decision would be respected if they refused any intervention (enema, shaving, etc.) (Table 1), which is often among the procedures not recommended by the World Health Organization [5]. The findings are comparable to those of a previous study where approximately 50% of the women indicated that they would decline any proposed intervention or screening [12]. The importance of awareness, sense of control, and the ability to refuse routine procedures and examinations during labor cannot be overstated. These factors require special attention with a focus on empowerment and respect for women in the context of midwifery in Slovakia.

The respectful approach of healthcare providers to women by encouraging immediate skin-to-skin contact (SSC) between mother and child was also investigated. The immediate and unimpeded SSC can be viewed as a process that facilitates the formation of a kinship bond, supported by a range of biological, immunological, physiological, and psychological processes. This bond has significant value for both mother and child. In our study, almost half of the respondents reported that they did not have the opportunity to have SSC with their baby immediately after delivery as recommended (Table 1). These results can be considered unsatisfactory given the benefits of early mother-infant contact. However, despite the unfavorable results, the situation in Slovakia is slowly and gradually improving.

Statistically significant differences were demonstrated between the degree of women՚s autonomy during labor and all respectful approach variables (respectful and deferential behavior of healthcare providers, respect for privacy and intimacy, respect for the rate of labor, freedom of movement in the delivery room, choice of delivery position, information about prearranged interventions or examinations, sense of control, ability to refuse interventions or examinations, and ability to facilitate bonding after delivery). Our findings are consistent with those of other studies [8, 19]. According to Vedam S. et al. [8], autonomy was lower in women who reported difficulties in communicating with their doctor. Nieuwenhuijze M.J. et al. also found that the ability to move freely and take different positions during labor is a significant predictor of women՚s autonomy in childbirth [20]. Similarly, a study conducted in Ghana showed that if women in labor were given information about different positions during labor, it had a positive effect on their autonomy and perception of labor [21]. Our findings are consistent with those of the study which also showed that autonomy is closely related to women՚s awareness [22]. It follows not only from our results, but also from the findings of Meyer S., that it is necessary to maintain women՚s sense of control over their labor in order to respect their autonomy [17]. Yuill C. et al. argue that there is considerable evidence for the importance of support and enhancement of multiple choice opportunities [23]. Informed choice in the context of caring for pregnant women is a choice that takes into account all the information gathered, is consistent with the woman՚s philosophy, and honors her wishes while maintaining bodily autonomy and integrity.

On the part of health professionals, it is important to emphasize psychosocial needs. Their knowledge is the starting point for assessing an individual՚s behavior, reactions and life priorities [24].

The findings of our study must be evaluated taking into account the limitations and constraints. Based on our study, it is not possible to generalize the results to the entire population, which we are fully aware of, especially because of the unrepresentative nature of the study sample, as a deliberate method was used to select female respondents. Factors related to a woman՚s degree of autonomy during labor are also limiting. We recognize that other variables that we did not include in our study may be related to the level of autonomy achieved by the woman during labor. Nevertheless, we believe that the findings provide a rationale for the implementation of this approach in actual practice in maternity hospitals.

Conclusion

The autonomy of the woman in labor should be supported as much as possible by all available means, such as proper communication, responding to the woman՚s needs and meeting these needs, avoiding unnecessary interference in the process of labor, respecting the physiology of labor and its rate, providing appropriate information, respecting the decisions and personal wishes of the woman in labor, ensuring privacy that also protects intimacy, creating conditions when the woman can move around during the first period of labor or freely choose the position for the birth, and ensuring that the woman is able to move around during the first period of labor or freely choose the position of birth according to her own feelings, ensuring that ther are all conditions to support mother-child bonding in the near postpartum period according to recommended procedures, etc. It is important to restore a woman՚s understanding that childbirth is a natural part of our lives and that she is the one who brings her child into the world and therefore has the right to participate in the process of childbirth herself. The recognition of the woman as a unique being is the basis for the humanization of childbirth.

References

- Attanasio L.B., Kozhimannil K.B., Kjerulff K.H. Factors influencing women's perceptions of shared decision making during labor and delivery: Results from a large-scale cohort study of first childbirth. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018; 101(6): 1130-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.002.

- Feijen-de Jong E.I., van der Pijl M., Vedam S., Jansen D.E.M.C., Peters L.L. Measuring respect and autonomy in Dutch maternity care: Applicability of two measures. Women Birth. 2020; 33(5): e447-e454. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.10.008.

- Wilhelmová R., Veselá L., Korábová, I., Slezáková S., Pokorná A. Determinants of respectful care in midwifery. Kontak. 2022; 24(4): 302-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.32725/kont.2022.035.

- Prosen M., Krajnc M.T. Sociological conceptualization of the medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth: the implications in Slovenia. Revija Za Sociologiju. 2013; 43(3): 251-72. https://dx.doi.org/10.5613/rzs.43.3.3.

- WHO. WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services. 2018; 200 p.

- Bohren M.A., Tunçalp Ö., Miller S. Transforming intrapartum care: Respectful maternity care. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020; 67: 113-26. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.02.005.

- Vedam S., Stoll K., Martin K., Rubashkin N., Partridge S., Thordarson D. et al.; Changing Childbirth in BC Steering Council. The Mother's Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale: Patient-led development and psychometric testing of a new instrument to evaluate experience of maternity care. PLoS One. 2017; 12(2): e0171804. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171804.

- Vedam S., Stoll K., McRae D.N., Korchinski M., Velasquez R., Wang J. et al.; CCinBC Steering Committee. Patient-led decision making: Measuring autonomy and respect in Canadian maternity care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019; 102(3): 586-94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.023.

- Iravani M., Zarean E., Janghorbani M., Bahrami M. Women's needs and expectations during normal labor and delivery. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2015; 4: 6. https://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2277-9531.151885.

- Reed R., Sharman R., Inglis C. Women's descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017; 17(1): 21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1197-0.

- Bohren M.A., Hofmeyr G.J., Sakala C., Fukuzawa R.K., Cuthbert A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017; 7(7): CD003766. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6.

- Mazúchová L., Kelčíková S., Štofaníková L., Kopincová J., Malinovská N., Grendár M. Satisfaction of Slovak women with psychosocial aspects of care during childbirth. Midwifery. 2020; 86: 102711. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102711.

- Mazúchová L., Kelčíková S., Štofániková L., Malinovská N. Women´s control and participation in decision-making during childbirth in relation to satisfaction. Cen. Eur. J. Nurs. Midw. 2020; 11(3): 136-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.15452/cejnm.2020.11.0021.

- Afulani P.A., Buback L., Kelly A.M., Kirumbi L., Cohen C.R., Lyndon A. Providers' perceptions of communication and women's autonomy during childbirth: a mixed methods study in Kenya. Reprod. Health. 2020; 17(1): 85. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0909-0.

- Reis T.L.D.R.D., Padoin S.M.M., Toebe T.R.P., Paula C.C., Quadros J.S. Women's autonomy in the process of labour and childbirth: integrative literature review. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2017; 38(1): e64677. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2017.01.64677.

- Hodnett E.D., Gates S., Hofmeyr G.J., Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013; 7: CD003766. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub5.

- Meyer S. Control in childbirth: a concept analysis and synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013; 69(1): 218-28. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06051.x.

- Olza I., Uvnas-Moberg K., Ekström-Bergström A., Leahy-Warren P., Karlsdottir S.I., Nieuwenhuijze M. et al. Birth as a neuro-psycho-social event: An integrative model of maternal experiences and their relation to neurohormonal events during childbirth. PLoS One. 2020; 15(7): e0230992. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230992.

- Sandall J., Soltani H., Gates S., Shennan A., Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016; 4(4): CD004667. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5.

- Nieuwenhuijze M.J., de Jonge A., Korstjens I., Budé L., Lagro-Janssen T.L. Influence on birthing positions affects women's sense of control in second stage of labour. Midwifery. 2013; 29(11): e107-14. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.12.007.

- Mensah R.S., Mogale R.S., Richter M.S. Birthing experiences of Ghanaian women in 37th Military Hospital, Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Africa Nurs Sci. 2014; 1: 29-34. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2014.06.001.

- Nigatu D., Gebremariam A., Abera M., Setegn T., Deribe K. Factors associated with women's autonomy regarding maternal and child health care utilization in Bale Zone: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2014; 14: 79. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-79.

- Yuill C., McCourt C., Cheyne H., Leister N. Women’s experiences of decision-making and informed choice about pregnancy and birth care: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20: 343. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03023-6.

- Novysedláková M., Kaiserová E. Psychosociálne aspekty chronického ochorenia. Zdravotnícke štúdie. 2015; 8(2): 36-8.

Received 26.08.2024

Accepted 28.10.2024

About the Authors

Lucia Mazúchová, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing and Midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery, Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia, lucia.mazuchova@uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9363-0922Andrea Porubská, MSN, a midwife at the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics in the A. Winter Hospital, Piešt’any, Slovakia, andrea.porubska2@gmail.com

Simona Kelčíková, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Public Health, Nursing, and Midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery, Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia, simona.kelcikova@uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2347-4343

Erika Maskalová, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing and Midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery, Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia, erika.maskalova@uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2806-4586

Nora Malinovská, MA, PhD, a lecturer in Medical Latin and English for Medical Purposes, History of Medicine at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Foreign Languages, Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia, 00421 432633520, nora.malinovska@uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5334-207X

Corresponding author: Nora Malinovská, nora.malinovska@uniba.sk