Postpartum hysterectomy: causes of obstetric hemorrhage and improved approach to surgical intervention

Objective: To improve the technique of postpartum hysterectomy in massive postpartum obstetric hemorrhage using an integrated approach which includes methods of surgical hemostasis and the placement of Zhukovsky vaginal and uterine catheters. Materials and methods: The study included 52 puerperas with massive obstetric hemorrhage who underwent hysterectomy to stop the bleeding. In order to assess the effectiveness of the hysterectomy method, the participants were divided into two groups: group 1 consisted of 23 women who used Zhukovsky vaginal and uterine catheters; group 2 included 29 puerperas who received traditional obstetric care. The effectiveness of treatment was assessed using two criteria: blood loss volume and transfusion volume. Results: There were the following causes of postpartum hemorrhage: placenta accreta – 25/52 (48.1%), uterine atony – 17/52 (32.7%), uteroplacental apoplexy complicating placental abruption – 8/52 (15.4), amniotic fluid embolism – 2/52 (3.8%). The total volume of blood loss was 1.3 times lower in the comparison group. Blood loss in multiparous women was 3500 ml, which was less (p=0.021) than in primiparous and secondiparous women (5000 ml). The use of Zhukovsky vaginal and uterine catheters during hysterectomy made it possible to reduce the volume of total blood loss by 1.3 times (p<0.001), reduce the volume of transfused fresh frozen plasma by 1.4 times (p<0.001), decrease erythrocyte mass by 1.4 times (p<0.001). Conclusion: The use of combined tactics during postpartum hysterectomy can reduce blood loss volume and decrease the risk of postoperative complications.Barinov S.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Nadezhina E.S., Lazareva O.V., Kovaleva Yu.A., Grebenyuk O.A., Razdobedina I.N.

Keywords

Uterine bleeding is a common complication of the postpartum period that can occur even in patients without predisposing risk factors. It is one of the main causes of maternal morbidity both in developing and developed countries. Most studies on this subject focus on the development of preventive techniques. Despite the fact that all preventive measures are carried out, it is not always possible to avoid complications. Uterine bleeding can be sudden, massive, uncontrolled and conservative therapy is ineffective in this case, therefore, there is a risk of loss of the reproductive organ followed by disability of the woman [1–3].

There are various risk factors for postpartum bleeding [4, 5]. They include an increase in the age of the mother (maternal age >35 years) and parity (>6 in the history), a large number of previous cesarean sections and a short period of time of abdominal delivery, multiple births [6, 7].

A number of authors consider that abnormal placentation, placenta accreta and placental abruption are the leading causes of the massive obstetric bleeding [8–14], others think that bleeding can be caused by uterine atony [15]. Ruptures of the uterus and soft tissues of the vagina are also supposed to contribute to the development of massive blood loss [16].

According to some authors, there are certain technical difficulties in performing hysterectomy, which are mainly associated with the difficulty of separating the uterovesical fold under extreme conditions of ongoing bleeding, the risk of injury to the ureter, bladder, loss of the vascular bundle [17].

Due to the fact that a significant part of hysterectomies is unpredictable, it is necessary to make a quick decision and choose a method of bleeding control in order to ensure the safety of patients in these cases. Therefore, medical institutions should have multidisciplinary teams that can improve the results and control the difficult medical and surgical complications that occur after childbirth [18–20].

The objective of the study is to improve the technique of postpartum hysterectomy in massive postpartum obstetric hemorrhage using an integrated approach which includes methods of surgical hemostasis and the placement of Zhukovsky vaginal and uterine catheters.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out in the Perinatal Center of the Regional Clinical Hospital in the Omsk region for the period from 2013 to 2020. The study included 52 puerperas with massive obstetric hemorrhage who underwent hysterectomy due to ineffective conservative methods of uterine bleeding control. The participants were divided into two groups: group 1 consisted of 23 women who used Zhukovsky vaginal and uterine catheters; group 2 included 29 puerperas who received traditional obstetric care. The effectiveness of the treatment was assessed using two criteria: blood loss volume and transfusion volume.

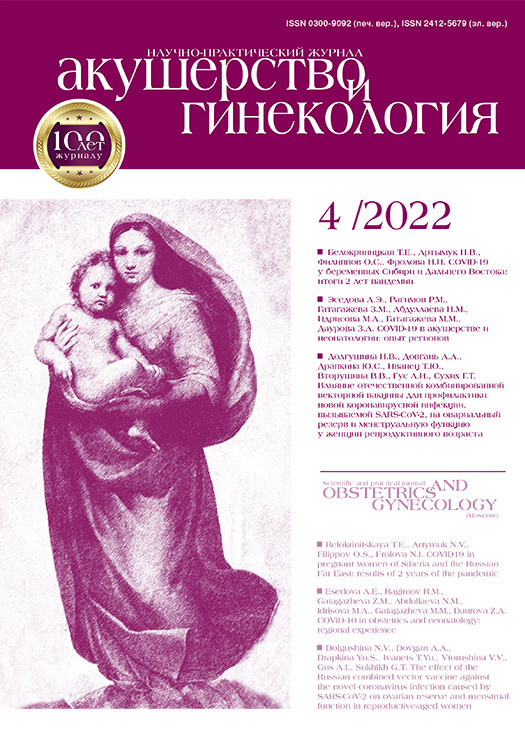

After spontaneous vaginal delivery of the patients in the main group, the following stages were used: intravenous injection of uterotonics, manual examination of the uterine cavity, placement of a uterine catheter into the uterine cavity, followed by its filling with saline solution; then, a vaginal catheter was placed which was also filled with a saline solution in the volume of 180 ml (Fig. 1); if the desired hemostatic effect was not achieved, then laparotomy followed by hysterectomy was performed in presence of catheters that had already been installed.

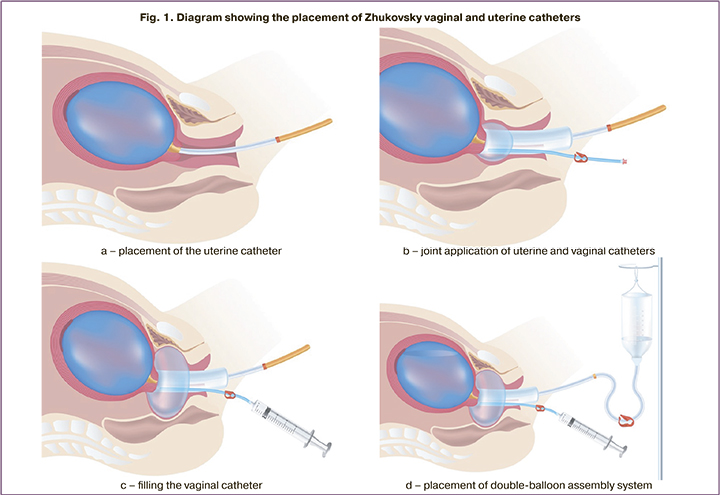

After cesarean section in the patients of the main group, a uterine catheter was immediately installed into the uterine cavity and filled with saline solution; then a vaginal catheter was placed next to it which was also filled with a saline solution in the volume of 180 ml. Subsequent tactics included a combination of surgical hemostatic techniques: bilateral ligation of the descending branch of the uterine artery and putting a hemostatic external uterine supraplacental pleated suture. If there was no hemostatic effect and uncontrolled bleeding developed, a hysterectomy was performed. In all cases, when the uterus was removed, the ligamentous apparatus was cut off; after the entrance to the vaginal vault, the uterine catheter was removed, and hysterectomy was performed with an installed vaginal catheter, which was in the vagina for 12–14 hours after the end of the operation (Fig. 2).

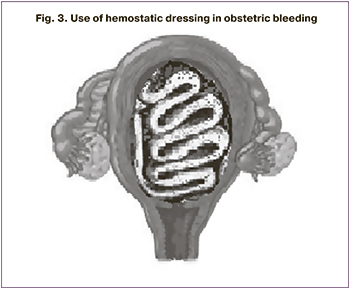

The patients of the comparison group received traditional obstetric care which included hemostatic techniques carried out in the following stages: manual examination, uterine tamponade with hemostatic bandage aimed at reducing the volume of blood loss (Fig. 3), hysterectomy when the effect was absent. Fresh frozen plasma, erythrocyte mass, thromboconcentrate, protease inhibitors were injected during transfusion therapy.

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Omsk State Medical University, Omsk, Russia (Ref. No.104 of 14/11/2013).

Statistical analysis

Statistical processing of the findings was performed using SAS 9.2, STATISTICA 10, and SPSS-20 software packages. The mean value (M) and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for normally distributed variables, and t-test was used for the comparison of two groups. The results were considered statistically significant at a level of p<0.05. Relative risk ratio with 95% confidence interval was calculated using contingency tables to compare the group for the rate of persistent bleeding after hysterectomy.

Results

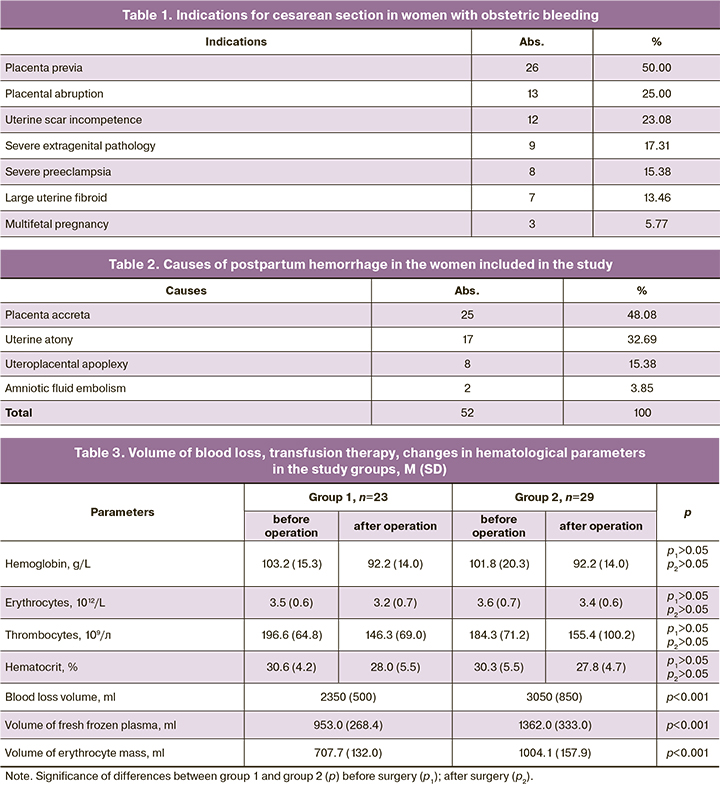

The average age of puerperas included in the study (n=52) was 30.1 (5.2) years. The women of both groups were compared in age, parity, and the causes of bleeding. Among them, there were 33/52 (63.5%) secundiparas, 7/52 (13.5%) primiparas, and 12/52 (23.1%) multiparas. Hysterectomy caused by obstetric bleeding after spontaneous delivery was performed in 9/52 (17.3%) cases, due to intraoperative bleeding in 16/52 (30.8%) cases, after cesarean section in 27/52 (51.9%) cases. The indications for cesarean section in women with hysterectomy included placenta previa in 26/52 (50.0%) pregnant women, placental abruption in 13/52 (25.0%) women, uterine scar incompetence in 12/52 (23.1%) cases, severe extragenital pathology in 9/52 (17.3%) women, severe preeclampsia in 8/52 (15.4%) women, large uterine fibroids in 7/52 (13.5%) patients and multifetal pregnancies in 3/52 (5.8%) patients (Table 1). A combination of indications for caesarean section was found in 26/52 (50.0%) women.

There were the following most common causes of postpartum hemorrhage that caused hysterectomy: placenta accreta – 25/52 (48.1%), uterine atony – 17/52 (32.7%), uteroplacental apoplexy complicating placental abruption – 8/52 (15.4), amniotic fluid embolism – 2/52 (3.8%) (Table 2). Therefore, the leading causes of obstetric bleeding were morphological changes in the structure of the myometrium and disorders of its contractile activity.

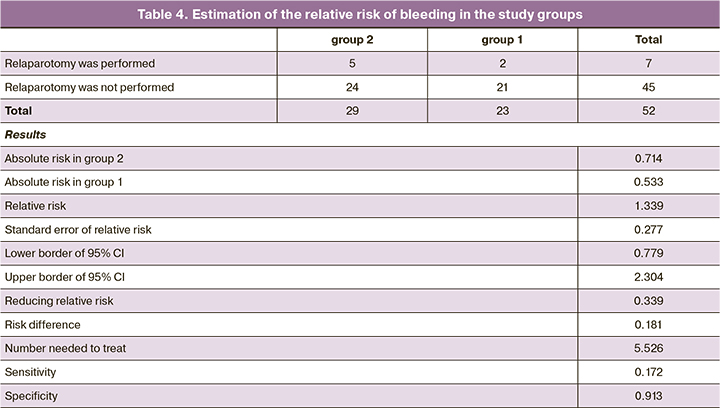

On further examination, we assessed the volume of total blood loss, changes in hematological parameters, the volume of transfused plasma and blood transfusion in the groups of patients. The assessment of the blood loss volume revealed that the total volume of blood loss in the comparison group was 1.3 times greater than in the main group, 3050 (850) ml versus 2350 (500) ml, respectively (p<0.001).

In our opinion, the volume of total blood loss depends on the parity and its assessment can be of particular interest. Thus, the maximum blood loss in multiparous women did not exceed 3500 ml and it was significantly less than in primiparous and secundiparous patients, whose total blood loss reached 5000 ml (p=0.021). This fact is obviously associated with a large number of methods of conservative bleeding control, which led to a later organ-resecting operation.

The volume and composition of infusions differed significantly in the study groups. The average volume of fresh frozen plasma administered in group 2 was 1362.0 (333.0) ml, in contrast to 953.0 (268.4) ml administered in group 1 (p<0.001). The volume of erythrocyte mass in group 2 was significantly higher than in group 1, 1004.1 (157.9) ml versus 707.7 (132.0) ml, respectively (p<0.001). The study of changes in hematological parameters did not reveal any statistically significant differences in the groups before and after the operation (Table 3).

Persistent bleeding occurred in seven cases after hysterectomy, which required relaparotomy. It was associated with coagulopathic bleeding from the area of the surgical wound in two cases of group 1; pelvic tamponade with gauze swabs was performed. In group 2, there were five relaparotomies due to persistent bleeding from the vessels of the parametrium with the formation of hematomas; additional hemostasis of the pelvic vessels was performed with subsequent tamponade; tampon was removed on the 3rd day of the postoperative period with a favorable outcome. In all cases, surgical interventions were carried out with placed vaginal catheter, which made it possible to improve the technical capabilities of the operation; the catheter was placed for 12 hours.

To assess the effectiveness of hysterectomy which was performed in the presence of placed Zhukovsky uterine and vaginal catheters, relative risk of bleeding in the study groups was estimated. The risk of recurrent bleeding in group 1 was found to be lower than in group 2, 0.533 versus 0.714, respectively. The relative risk is 1.339 (95% CI: 0.779–2.304), which is not statistically significant (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of our study showed that the main cause of massive postpartum bleeding is morphological changes in the structure of the myometrium associated with placenta accreta (48.08%) or caused by placental abruption (15.38%). Another reason for the postpartum pathology is the impairment of contractile activity of the lower segment with uterine atony (32.69%) due to multifetal pregnancy or uterine scar incompetence. In these situations, conservative measures are not always effective, therefore, it is necessary to perform a hysterectomy to save the life of a woman who has just given a birth; these findings are consistent with the data of other authors [21–24].

Postpartum hysterectomy is a technically complex surgical intervention where knowledge of the anatomy of the pelvis, vascular plexuses of the retroperitoneal space, surgical technique and surgeon’s skills, including special techniques of hemostasis and dissection, are important for a positive result of the operation; and approach should be individualized as well [25, 26]. Reducing the volume of external blood loss is also of particular importance. A number of authors suggest placing a uterine catheter in combination with putting compression sutures to reduce external blood loss; however, when performing hysterectomy, there is a risk for the uterine catheter to pass out of the uterine cavity [27, 28]. The additional placement of a vaginal catheter can ensure the stability of the uterine catheter in the uterine cavity. Moreover, high placement of the catheter in the vagina prevents the uterine catheter from expulsion and reduces the volume of external blood loss due to inter-balloon compression by uterine and vaginal catheters of the lower uterine segment [29].

According to Dogan O. et al. (2017), obstetric bleeding causes difficulties in performing hysterectomy, namely, in determining the real border of the cervix after vaginal delivery. The authors suggest using two atraumatic ring forceps on the anterior and posterior sides of the cervix during preoperative vaginal examination [30]. At the same time, the installed vaginal catheter helps to determine the borders of the vaginal fornices and prevents the vaginal stump wall from sliding during uterine dissection, which is important in reducing blood loss.

The installed vaginal catheter applies mechanical pressure on the systems of uterine and vaginal arteries, and various branches of internal pudendal artery; it prevents the risk of pelvic hematomas, and leads to a favorable outcome of postpartum hysterectomy. Therefore, it is necessary to perform surgical interventions using an installed vaginal catheter in cases of repeated bleeding after hysterectomy.

Conclusion

Thus, the main causes of massive obstetric bleeding are placenta accreta (48.08%), uterine atony (32.69%), uteroplacental apoplexy complicating placental abruption (15.38%), and amniotic fluid embolism (3.85%).

The use of combined approach including methods of surgical hemostasis (ligation of the descending branch of the uterine artery, hemostatic external uterine supraplacental pleated suture) and placement of Zhukovsky vaginal and uterine catheters reduces the volume of total blood loss by 1.3 times, decreases the volume of transfused fresh frozen plasma by 1.4 times and erythrocyte mass by 1.4 times.

References

- Курцер М.А., Бреслав И.Ю., Латышкевич О.А., Григорьян А.М. Временная баллонная окклюзия общих подвздошных артерий у пациенток с рубцом на матке после кесарева сечения и placenta accrete, преимущества и возможные осложнения. Акушерство и гинекология. 2016; 12: 70-5. [Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Latyshkevich O.A., Grigoryan A.M. Temporary balloon occlusion of common iliac arthriasis in patients with uterine scar after cesarean section and placenta accreta: Advantages and possible complications. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016; 12: 70-5 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2016.12.70-5.

- Zhang Y., Yan J., Han Q., Yang T., Cai L., Fu Y. et al. Emergency obstetric hysterectomy for life-threatening postpartum hemorrhage: A 12-year review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96(45): e8443. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000008443.

- Hajmurad O.S., Choxi A.A., Zahid Z., Dudaryk R. Aortoiliac thrombosis following tranexamic acid administration during urgent cesarean hysterectomy: a case report. A Case Rep. 2017; 9(3): 90-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1213/XAA.0000000000000535.

- Senturk M.B., Cakmak Y., Guraslan H., Dogan K. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: 2-year experiences in non-tertiary center. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015; 292(5): 1019-25. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3740-z.

- Malinowska-Polubiec A., Romejko-Wolniewicz E., Zareba-Szczudlik J., Dobrowolska-Redo A., Sotowska A., Smolarczyk R. et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy – a challenge or an obstetrical defeat? Neuro Endocrinol; Lett. 2016; 37(5): 389-94.

- Campbell S.M., Corcoran P., Manning E., Greene R.; Irish Maternal Morbidity Advisory Group. Peripartum hysterectomy incidence, risk factors and clinical characteristics in Ireland. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016; 207: 56-61. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.10.008.

- Sikora-Szczęśniak D.L., Szczęśniak G., Szatanek M., Sikora W., Sikora-Szczęśniak D. Clinical analysis of 52 obstetric hysterectomies. Ginekol. Pol. 2016; 87(6): 460-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.5603/GP.2016.0026.

- Calvo-Aguilar O., Vásquez-Martínez J., Hernández-Cuevas P. Obstetric hysterectomy in the General Hospital Dr. Aurelio Valdivieso: three-year review. Ginecol. Obstet. Mex. 2016; 84(2): 72-8.

- Temizkan O., Angın D., Karakuş R., Şanverdi İ., Polat M., Tahaoglu A.E. et al. Changing trends in emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary obstetric center in Turkey during 2000-2013. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2016; 17(1): 26-34. https://dx.doi.org/10.5152/jtgga.2015.16239.

- Chen J., Cui H., Na Q., Li Q., Liu C. Analysis of emergency obstetric hysterectomy: the change of indications and the application of intraoperative interventions. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2015; 50(3): 177-82.

- Pan X.Y., Wang Y.P., Zheng Z., Tian Y., Hu Y.Y., Han S.H. A Marked increase in obstetric hysterectomy for placenta accreta. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 2015; 128(16): 2189-93. https://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.162508.

- Begum M., Alsafi F., ElFarra J., Tamim H.M., Le T. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary care hospital in saudi arabia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India. 2014; 64(5): 321-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13224-013-0423-1.

- Matsuzaki S., Yoshino K., Kumasawa K., Satou N., Mimura K., Kanagawa T. et al. Placenta percreta managed by transverse uterine fundal incision with retrograde cesarean hysterectomy: a novel surgical approach. Clin. Case Rep. 2014; 2(6): 260-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.108.

- Виницкий А.А., Шмаков Р.Г. Современные представления об этиопатогенезе врастания плаценты и перспективы его прогнозирования молекулярными методами диагностики. Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 2: 5-10. [Vinitsky A.A., Shmakov R.G. Modern ideas about the etiopathogenesis of placenta ingrowth and the prospects for its prediction by molecular diagnostic methods. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017; 2: 5-10 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.2.5-10.

- Huls C.K. Cesarean hysterectomy and uterine-preserving alternatives. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North. Am. 2016; 43(3): 517-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2016.04.010.

- Fawad A., Islam A., Naz H., Nelofar T., Abbasi U.N. Emergency peri partum hysterectomy-a life saving procedure. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2015; 27(1): 143-5.

- Palacios-Jaraquemada J.M. Caesarean section in cases of placenta praevia and accreta. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013; 27(2): 221-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.10.003.

- Friedman A.M., Wright J.D., Ananth C.V., Siddiq Z., D'Alton M.E., Bateman B.T. Population-based risk for peripartum hysterectomy during low- and moderate-risk delivery hospitalizations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 215(5): 640.e1-640.e8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.032.

- Jakobsson M., Tapper A.M., Colmorn L.B., Lindqvist P.G., Klungsøyr K., Krebs L. et al.; NOSS Study Group. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: results from the prospective Nordic Obstetric Surveillance Study (NOSS). Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015; 94(7): 745-54. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12644.

- Gillespie C., Sangi-Haghpeykar H., Munnur U., Suresh M.S., Miller H., Hawkins S.M. The effectiveness of a multidisciplinary, team-based approach to cesarean hysterectomy in modern obstetric practice. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2017; 137(1): 57-62. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12093.

- Tahaoglu A.E., Balsak D., Togrul C., Obut M., Tosun O., Cavus Y. et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: our experience. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2016; 185(4): 833-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11845-015-1376-4.

- De la Cruz C.Z., Thompson E.L., O'Rourke K., Nembhard W.N. Cesarean section and the risk of emergency peripartum hysterectomy in high-income countries: a systematic review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015; 292(6): 1201-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3790-2.

- Пенжоян Г.А., Макухина Т.Б., Мингалева Н.В., Солнцева А.В., Амирханян А.М. Менеджмент пациенток с врастанием плаценты на разных сроках гестации. Акушерство и гинекология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2019; 7(1): 79-84. [Penzhoyan G.A., Makukhina T.B., Mingaleva N.V., Solntseva A.V., Amirkhanyan A.M. Management of patients with placenta accreta at different gestational ages. Obstetrics and Gynecology: News, Opinions, Training. 2019; 7(1): 79-84 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2303-9698-2019-11011.

- Забелина Т.М., Васильченко О.Н., Каримова Г.Н., Ежова Л.С., Учеваткина П.В., Шмаков Р.Г. Родоразрешение беременных с врастанием плаценты без рубца на матке. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 4: 150-6. [Zabelina T.M., Vasilchenko O.N., Karimova G.N., Ezhova L.S., Uchevatkina P.V., Shmakov R.G. Delivery ofpregnant women with placenta increta and no uterine scar. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 4: 150-6. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.4.150-156.

- Soleymani Majd H., Collins S.L., Addley S., Weeks Е., Chakravarti S., Halder S. et al. The modified radical peripartum cesarean hysterectomy (Soleymani-Alazzam-Collins technique): a systematic, safe procedure for the management of severe placenta accreta spectrum. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021; 225(2): 175.e1-175.e10. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.014.

- Palacios-Jaraquemada J.M., Fiorillo A., Hamer J., Martínez M., Bruno C. Placenta accreta spectrum: a hysterectomy can be prevented in almost 80% of cases using a resective-reconstructive technique. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022; 35(2): 275-82. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1716715.

- Colmorn L.B., Krebs L., Langhoff-Roos J.; NOSS Study Group. Potentially avoidable peripartum hysterectomies in Denmark: A population based clinical audit. PLoS One. 2016; 11(8): e0161302. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161302.

- Lo A., Yadav P., Belisle E., Markenson G. The impact of Bakri balloon tamponade on the rate of postpartum hysterectomy for uterine atony. J Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017; 30(10): 1163-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1208742.

- Barinov S., Tirskaya Y., Medyannikova I., Shamina I., Shavkun I. A new approach to fertility-preserving surgery in patients with placenta accreta. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019; 32(9): 1449-53. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1408066.

- Dogan O., Pulatoglu C., Yassa M. A new facilitating technique for postpartum hysterectomy at full dilatation: Cervical clamp. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018; 81(4): 366-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcma.2017.05.010.

Received 02.02.2022

Accepted 16.03.2022

About the Authors

Sergey V. Barinov, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(913)633-80-48; barinov_omsk@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0357-7097, 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin's str., 12.Irina V. Medyannikova, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University,

Ministry of Health of Russia, mediren@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6892-2800, 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin's str., 12.

Yulia I. Tirskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University,

Ministry of Health of Russia, yulia.tirskaya@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5365-7119, 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin's str., 12.

Tatyana V. Kadtsyna, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, tatianavlad@list.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0348-5985, 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin's str., 12.

Evgenia S. Nadezhina, obstetrician-gynecologist at the Obstetric Physiological Department, Perinatal Center of Regional Clinical Hospital, mec86.86@mail.ru,

644111, Russia, Omsk, Berezovaya str., 3.

Oksana V. Lazareva, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

lazow@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0895-4066, 644099, Russia, Omsk, Lenin's str., 12.

Yulia A. Kovaleva, obstetrician-gynecologist, Head of the Obstetric Department of Pregnancy Pathology, Perinatal Center of Regional Clinical Hospital,

kovalevajulia71@yandex.ru, 644111, Russia, Omsk, Berezovaya str., 3.

Olga A. Grebenyuk, PhD, Head of the Obstetric Physiological Department, Perinatal Center of Regional Clinical Hospital, olgaomsk@inbox.ru,

644111 Russia, Omsk, Berezovaya str., 3.

Irina N. Razdobedina, obstetrician-gynecologist, Head of the Obstetric Observational Department, Perinatal Center of Regional Clinical Hospital, irina.razdobedina@yandex.ru, 644111, Russia, Omsk, Berezovaya str., 3.

Corresponding author: Sergey V. Barinov, barinov_omsk@mail.ru

Authors’ contributions: Barinov S.V. – developing the design and concept of the study, editing; Medyannikova I.V. – writing the text, statistical processing; Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Nadezhina E.S., Lazareva O.V., Kovaleva Yu.A., Grebenyuk O.A., Razdobedina I.N. – collection of the material, data processing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: The study was performed without external funding.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Omsk State Medical University

(Ref. No.104 of 14/11/2013).

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Barinov S.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Nadezhina E.S., Lazareva O.V., Kovaleva Yu.A., Grebenyuk O.A., Razdobedina I.N. Postpartum hysterectomy: causes of obstetric hemorrhage and improved approach to surgical intervention.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 4: 95-102 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.4.95-102