Ultrasound examination of the cesarean scar in the prognosis of pregnancy outcome

Objective. To study the state and time of thinning of uterine scars after cesarean section (CS) in pregnant women using ultrasound monitoring.Zemskova N.Yu., Chechneva M.A., Petrukhin V.A., Lukashenko S.Yu.

Materials and methods. The study included 148 pregnant women at periods of 6–12, 13–20, 21–29, 30–36 and 37–40 weeks gestation; the patients were divided into groups based on the initial thickness of the residual myometrium in the scar area; pregnancy outcomes were studied.

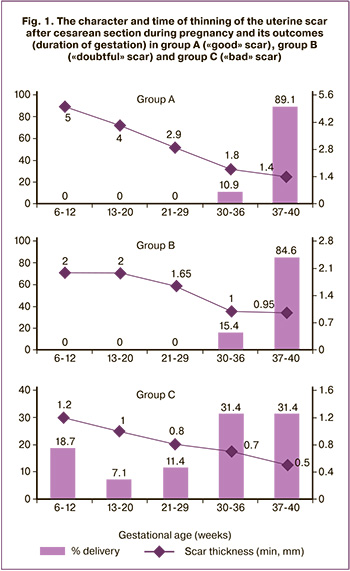

Results. Patients in group A whose residual myometrium was more than 3 mm had a late (by 37 weeks) and gradual (on average, 1 mm per trimester) thinning of the scar. The outcomes were a full-term pregnancy in 89.1% of patients, and preterm delivery at 30–36 weeks in 10.9% of cases (vaginal delivery in 17.2%, CS in 82% of cases).

Patients of group B whose residual myometrium was 2–3 mm had a full-term pregnancy in 84.6% of cases, preterm delivery at 30–36 weeks in 15.4% (CS in 92.3%; CS and hysterectomy in 7.3% of cases). Pregnant women in group C had residual myometrium less than 2 mm, and its thickness was less than 1 mm in 45.7% of them at 26 weeks of gestation. Patients in this group had a high incidence of placenta previa and placenta increta (11.3%) and adverse outcomes (full-term pregnancy in 31.4%, preterm delivery at 30–36 weeks in 31.4%, preterm delivery at 22–29 weeks in 11.4% of cases). CS was performed in 57.7%, CS and metroplasty were done in 8.5%, CS and hysterectomy were performed in 5.65% of cases. Preterm delivery at 22 weeks was noted in 28.1% of cases (metroplasty – 22.5%, hysterectomy – 5.65%).

Conclusion. Pregnant women whose residual myometrium is 1 mm thick or less in the period up to 26 weeks gestation are an extremely high-risk group and require special monitoring (it is recommended to perform ultrasonography at 12, 18, 22, and 26 weeks gestation).

Keywords

The rate of abdominal delivery has recently increased, though it was recommended by the World Health Organization (1985) to range from 10–15%; according to University of Edinburgh (2016), the frequency of cesarean section (CS) is currently 24.5% in Western Europe (38.1% in Italy), 32% in North America, 41% in South America, and more than 50% in some countries (Brazil, Turkey, Egypt). Even in Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology, which consistently takes a stand for vaginal delivery, there is an increased incidence of CS due to the high rate of pregnant women with severe extragenital pathology, bad obstetric history and pregnancy complications; CS has increased by more than 10% in the last 10 years (24.9% in 2009, 35.7% in 2019; 20.3% in the Moscow region in 2009, and 26.4% in 2019). During last 11 years, 208,443 caesarean sections were performed in Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Moscow region. The search for a method that can predict the probability of complications associated with the presence of a uterine scar after CS is becoming more and more relevant, and the development of protocols for predicting the possibility of complications is of particular interest [1, 2]. Postpartum endometritis, traumatic damage to the endometrium and myometrium due to technical difficulties in the CS process, ischemia of repair zones as a result of systemic diseases and complications of pregnancy and childbirth can contribute to the formation of an incompetent uterine scar [3]. The presence of undifferentiated connective tissue dysplasia can also contribute to the disorders of neoangiogenesis in the uterine scar [4]. The course of pregnancy in a patient with a uterine scar may be noted by severe complications, such as termination of pregnancy or uterine rupture [5]. Recently, there has been a significant increase in the placental attachment disorders and placental invasions [5, 6]. One of the main methods for assessing the state of the uterine scar during pregnancy is ultrasound assessment. Information about the diagnostic value and capabilities of transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound examination differs significantly in Russian and foreign studies, therefore, tactical approaches remain ambiguous [7–11]. Due to the significant increase in the rate of abdominal delivery, it is particularly important to study and systematize knowledge on diagnostics (including ultrasound) and management of patients with uterine scar after CS for the prevention of severe and fatal complications and successful completion of pregnancy.

Materials and Methods

This was a study of 148 women with a uterine scar after CS during the gestational period; the outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth were evaluated. The examination was performed at periods of 6–12, 13–20, 21–29, 30–36 and 37–40 weeks gestation using the device VOLUSON E 10, convex probe C 2–9 and vaginal probe RIC 5–9 D. On the basis of expert assessment of scars after the first consultation (in the first trimester of pregnancy), the patients were divided into three groups: group A consisted of patients with a “good” scar, group B had patients a “doubtful” scar, and group C consisted of patients with a “bad” scar. The following characteristics were considered as criteria: the presence/absence of malformations, “niches” (if they were present, they were measured in the longitudinal and transverse sections and localization was described), areas of retraction from the serous membrane, liquid structures; the presence of blood flow, and the thickness of the residual myometrium in the scar area was measured. The uterine scar was considered to be competent in case of absent malformations, “niches”, areas of retraction from the serous membrane and uterine cavity, or if residual myometrium in the scar area was more than 3 mm (in the first trimester), and also in case of the presence of a blood flow. According to the expert assessment, three groups were formed:

- group A included 64 patients with a “good” scar characterized by the residual myometrium in the area of the scar of 3 mm or more, presence of blood flow;

- group B consisted of 13 patients with a “doubtful” scar characterized by the residual myometrium in the area of the scar of 2-3 mm, and the presence of some of the above-described signs of an incompetent scar;

- group C included 71 patients with a “bad” scar characterized by the presence of the above–mentioned signs of an incompetent scar, residual myometrium in the area of the scar less than 2 mm (this parameter is determined by the resolution of modern ultrasound devices – reliable visualization of objects more than 2 mm), up to the complete absence of myometrium in some areas.

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric methods of mathematical statistics were used for mathematical processing of the material. When analyzing quantitative parameters (variational series), the data were presented as medians of the parameters Me and quartiles Q1 and Q3 in the format Me (Q1; Q3). The range of values (minimum and maximum values) was used in the description of the values. Differences in distributions were given in the form of p values; when interpreting the results of statistical analysis, the significance level p=0.05 was taken as critical. The differences were considered statistically significant when the parameter p<0.05, and p<0.001 was indicated for values close to zero. The research was partially supported by Scientific Research Institute for System Analysis, Russian Academy of Sciences; project No. 0065-2019-0007.

Results

The age of patients was comparable and was 32 (29; 36) years in group A, 33 (30; 39) years in group B, and 31 (29; 34) years in group C. The minimum age was 20 years, the maximum age was 58 years (pregnancy following ART). Various extragenital diseases were found in 93 (62.8%) pregnant women; there were no statistically significant differences among the groups, and there were fewer cardiovascular diseases (11.3%) in group C compared to ones in group A (26.6%).

Bad obstetric history was noted in 18 (12.2%) patients: 11 (17.2%) in group A, 2 (15.4%) in group B, and 5 (7%) in group C. Perinatal losses were reported in 10 (6.8%) women: 5 (2 antenatal, 2 intranatal, and 1 postnatal) in group A, 1 (intranatal) in group B, and 4 (2 antenatal, 1 intranatal, 1 postnatal) in group C. Pregnancy complications (anemia, edema in pregnant women, gestational diabetes mellitus) were observed in 75 (50.7%) patients: 31 (48.4%) in group A, 8 (61.5%) in group B, 36 (50.7%) in group C. It was noted that there was a high incidence of gestational diabetes in 24 (16.2%) of 148 pregnant women, which exceeds the population indicators (there were no statistically significant differences in the groups, namely, 14.1%, 30.8% and 15.5%, respectively).

The number of operations preceding this pregnancy had a direct impact on the quality of the uterine scar and pregnancy outcomes. Our study showed that the risk of complications increases with each subsequent CS. Thus, placental increta was present in 2 out of 8 patients with a history of three CS (25%). There were 7 patients out of 8 (87.5%) with the history of three CS in group C with unfavorable outcomes. There were only 1.6% of patients with good outcomes in group A and 9.9% of patients with good outcomes in group C; the differences were statistically significant, p=0.04. Outcomes in patients with the history of three CS were unfavorable: preterm delivery before 30 weeks gestation was performed in 5 out of 8 pregnant women: CS was in 3 women; CS and metroplasty were in 1 patient; CS and hysterectomy were in 1 patient; removal of a fetus and metroplasty were in 3 women. Thus, despite technical difficulties (the fourth CS), metroplasty was performed in 4 (50%) of 8 pregnant women in this group, which made it possible to preserve reproductive function.

We noted an increase in placental attachment disorders and placental invasions in patients with uterine scars after CS, especially in group C. Thus, placenta previa was found in 9 (6.1%) out of 148 pregnant women with a uterine scar: 1 (1.6%) patient in group A and 8 (11.3%) patients in group C.

According to the literature, about 10% of profuse bleeding and organ-resecting operations in obstetrics are caused by an abnormal delivery of the placenta due to different variants of placenta accrete. Chen J.S. et al. [12] reported that during delivery blood loss in such patients is 1–9 liters or more, maternal mortality is up to 30%, and perinatal mortality is up to 33.3% due to the high frequency of preterm birth, massive blood loss, and difficulties in entering the abdominal cavity and delivering the fetus.

According to the literature, about 10% of profuse bleeding and organ-resecting operations in obstetrics are caused by an abnormal delivery of the placenta due to different variants of placenta accrete. Chen J.S. et al. [12] reported that during delivery blood loss in such patients is 1–9 liters or more, maternal mortality is up to 30%, and perinatal mortality is up to 33.3% due to the high frequency of preterm birth, massive blood loss, and difficulties in entering the abdominal cavity and delivering the fetus.

The histological study showed that 9 (6.1%) patients had signs of placenta increta: 1 (7.7%) patient from group B and 8 (11.3%) patients from group C. These findings were obtained in the study of the material after radical operations; there was a patient whose placenta had grown into the bladder (resection was performed).

Ultrasound monitoring was performed throughout the entire gestation period, at the periods of 6–12, 13–20, 21–29, 30–36, and 37–40 weeks.

The character and time of thinning of the uterine scar after CS during pregnancy and its outcomes (duration of gestation) in group A (“good” scar), group B (“doubtful” scar) and group C (“bad” scar) are shown in Figure 1.

As it is shown in Figure 1, all initially “good” scars became thinner in later stages, they thinned gradually by 37 weeks gestation, decreasing about 1 mm per trimester (the median of the minimum thickness of the residual myometrium in group A was 1.4 mm in full-term pregnancy).

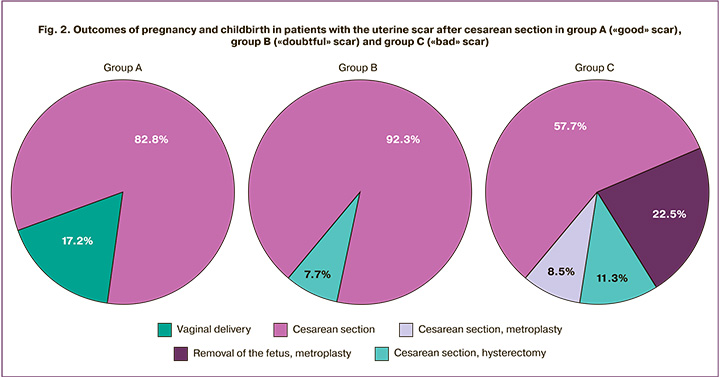

The outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth in patients with a uterine scar after CS (Fig. 2) in group A were favorable: 57 (89.1%) women had full-term pregnancies. Vaginal delivery occurred in 11 (17.2%) women, and 53 (82.8%) women had operative delivery.

The patients with “doubtful” scars (2–3 mm residual myometrium) in group B had less favorable outcomes: 11 (84.6%) patients had full-term pregnancies and 2 (15.4%) patients had pre-term deliveries at 30–36 weeks. There were no vaginal deliveries, CS was done in 12 (92.3%) cases; CS and hysterectomy were performed in 1 (7.7%) case at 34 weeks of pregnancy (Fig. 2).

Almost half of the pregnant women, namely 32 (45.7%), in group C had a residual myometrium thickness of less than 1 mm by 26 weeks gestation, the minimum parameter of the residual myometrium before delivery was 0.1 (0.1;0.1) mm.

During pregnancy, 20 patients with this (early) type of scar thinning had complications with an unfavorable outcome (10 patients had fetal loss and metroplasty, 10 patients had delivery before 30 weeks gestation; most radical operations were also performed in this group).

There were the following pregnancy outcomes in patients with uterine scar after CS in group C:

- removal of the fetus and metroplasty, 16 (22.5%) patients, during 7–21 weeks gestation;

- removal of the fetus and hysterectomy, 4 (5.65%) patients, during 18–21 weeks gestation;

- CS, 41 patients (57.7%);

- CS and metroplasty, 6 patients (8.5%);

- CS and hysterectomy, 4 patients (5.65%), at 30, 34, 37, weeks gestation;

- Vaginal delivery, 0 cases.

Our main priority was to perform organ-preserving operations. When increasing the extent of operations in group C (“bad” scars), 22 patients out of 30 (73.3%) underwent metroplasty; hysterectomy was performed only if metroplasty was not possible (extensive scarring of the isthmus / lower segment due to the previous operations, placenta increta, profuse bleeding).

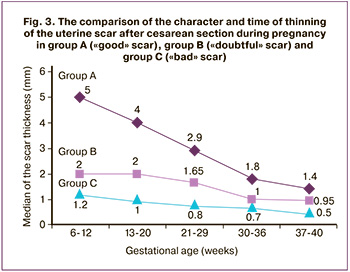

The comparison of the character and time of thinning of uterine scars after CS during pregnancy in group A (“good” scar), group B (“doubtful” scar) and group C (“bad” scar) is shown in Figure 3. In group A (“good” scar) there was a safe thinning (the type of curve is “children’s slide”), with a margin of safety due to the existing (more than 3 mm) residual myometrium; in group B and especially in group C there was an early thinning of the minimal reserve of the myometrium already in the second trimester which contributed to the development of complications.

The comparison of the character and time of thinning of uterine scars after CS during pregnancy in group A (“good” scar), group B (“doubtful” scar) and group C (“bad” scar) is shown in Figure 3. In group A (“good” scar) there was a safe thinning (the type of curve is “children’s slide”), with a margin of safety due to the existing (more than 3 mm) residual myometrium; in group B and especially in group C there was an early thinning of the minimal reserve of the myometrium already in the second trimester which contributed to the development of complications.

The intraoperative assessment of scars and the assessment of scars during the vaginal delivery showed that 29 (45.3%) women in group A had a competent scar, and 35 (54.7%) had a thin one. In group B, 11 (84.6%) patients had thin scars, 1 (7.7%) patient had hernia (aneurysm) of the scar, and 1 (7.7%) patient had uterine scar rupture. In group C, 1 (1.4%) scar was described as competent, 39 (54.9%) scars were described as thin, 28 (39.4%) scars were characterized as incompetent, but without rupture, 2 (2.8%) scars were described as hernias (aneurysms), and 1 (1.4%) scar was described as uterine scar rupture. The differences between groups A and B, as well as between A and C, had a high degree of statistical significance, in both cases p<0.001.

It is worth noting that a group of pregnant women that proved to be interesting from our point of view is 14 (9.5%) out of 148 examined women who had metroplasty performed during the previous CS or at the stage of preconception care. The scar became thinner (less than 1 mm) in 2 (14.3%) of them before 30 weeks of pregnancy, in 3 (21.4%) of them after 30 weeks, and there was no scar thinning in 9 (64.3%) of them. In the first trimester in this subgroup, the thickness of the myometrium was 3.4 (1.75; 5.7) mm, and the thickness of the myometrium before delivery was 1.1 (0.5; 1.9) mm. The outcomes were favorable: CS was performed in 14 patients, repeated metroplasty was performed in one of them.

Discussion

We believe that the expert assessment of the uterine scar after CS in pregnant women and the assessment of the risk of possible complications should be carried out immediately, when signs of thinning of the scar and/ or isthmocele are detected by specialists of ultrasound diagnostics (women’s consultations, clinics, etc.) and/or clinicians. Our study showed that all initially “good” scars became thinner later, namely by 37 weeks gestation, i.e. by the period of prenatal hospitalization, and thinning occurred according to the same pattern, i.e. quite predictably. Based on this, it is impractical to examine repeatedly, almost monthly, the initially “good” uterine scars during gestation only for detecting their presence (except for the clinical situations or the need for examination by experts). In other words, these patients can be monitored according to the standard protocol and then carefully evaluated in the hospital from the perspective of vaginal delivery, if it is planned.

If there is an initial assessment of scars as “bad” or “doubtful” (therefore, an early expert examination is important) it is reasonable to examine them more often, at 12, 18, 22, 26 weeks gestation; this period is recommended on the basis of the analysis of the pregnancy course, the time of reduction of the residual myometrium thickness to a critical one, and the outcomes in the group of “bad” scars.

Conclusion

Pregnant women whose residual myometrium is 1 mm thick or less in the period up to 26 weeks gestation are an extremely high-risk group and require special monitoring (the critical periods are 12, 18, 22, and 26 weeks gestation).

References

- Сухих Г.Т., Донников А.Е., Кесова М.И., Кан Н.Е., Амирасланов Э.Ю., Климанцев И.В., Санникова М.В., Ломова Н.А., Сергунина О.А., Демура Т.А., Коган Е.А., Абрамов Д.Д., Кадочникова В.В., Трофимов Д.Ю. Оценка состояния рубца матки с помощью математического моделирования на основании клинических и молекулярно-генетических предикторов. Акушерство и гинекология. 2013; 1: 33-9. [Sukhikh G.T. Donnikov A.E., Kesova M.I., Kan N.E., Amiraslanov E.Yu., Klimantsev I.V. et al. Assessment of the state of the uterine scar using mathematical modeling based on clinical and molecular genetic predictors. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013; 1: 33-9. (in Russian)].

- Краснопольский В.И., ред. Кесарево сечение. Проблемы абдоминального акушерства. Руководство для врачей. 3-е изд. М.: СИМК; 2018. [Cesarean section. Problems of Abdominal Obstetrics: A Guideline for Physicians. Ed. Academician of the RAS V.I. Krasnopolsky. 3rd ed., Revised. and add. M.: Special publishing house of medical books (SIMK); 2018. (in Russian).

- Щукина Н.А., Буянова С.Н., Чечнева М.А., Земскова Н.Ю., Баринова И.В., Пучкова Н.В., Благина Е.И. Основные причины формирования несостоятельного рубца на матке после кесарева сечения. Российский вестник акушера-гинеколога. 2018; 18(4): 57-61. [Schukina N.A., Buyanova S.N., Chechneva M.A., Zemskova N.Yu., Barinova I.V., Puchkova N.V. et al. The main reasons for the formation of an insolvent cesarean scar after cesarean section. Russian Bulletin of the Obstetrician-Gynecologist. 2018; 18(4): 57-61. (in Russian)].

- Сухих Г.Т., Коган Е.А., Кесова М.И., Демура Т.А., Донников А.Е., Мартынов А.И., Трофимов Д.Ю., Климанцев И.В., Санникова М.В., Кан Н.Е., Костин П.А., Орджоникидзе Н.В., Амирасланов Э.Ю. Морфологические и молекулярно-генетические особенности неоангиогенеза в рубце матки у пациенток с недифференцированной дисплазией соединительной ткани. Акушерство и гинекология. 2010; 6: 23-7. [Sukhikh G.T., Kogan E.A., Kesova M.I., Demura T.A., Donnikov A.E., Martynov A.I. et al. Morphological and molecular genetic features of neoangiogenesis in the uterine scar in patients with undifferentiated connective tissue dysplasia. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2010; 6: 23-7. (in Russian)].

- Schaap T., Bloemenkamp K., Deneux-Tharaux C., Knight M., Langhoff-Roos J., Sullivan E. et al. Defining definitions: a Delphi study todevelop a core outcome set for conditions of severe maternalmorbidity. BJOG. 2019; 126(3): 394-401. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14833.

- Thurn L., Lindqvist P.G., Jakobsson M., Colmorn L.B., Klungsoyr K., Bjarnadottir R.I. et al. Abnormally invasive placenta-prevalence, riskfactors and antenatal suspicion: results from a large population-based pregnancy cohort study in the Nordic countries. BJOG. 2016; 123(8): 1348-55. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13547.

- Van der Voet L.F., Jordans I.P.M., Brolmann H.A.M., Veersema S., Huirne J.A.F. Changes in the uterine scar during the first year after a Caesarean section: a prospective longitudinal study. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2018; 83(2): 164-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000478046.

- Серов В.Н., Сухих Г.Т., ред. Клинические рекомендации. Акушерство и гинекология. 4-е изд. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2014. 1024с. [Serov V.N., Sukhikh G.T., ed. Clinical recommendations. Obstetrics and gynecology. 4th ed., Revised. and add. M.: GEOTAR-Media; 2014. 1024 p. (in Russian)].

- Osser O.V., Jokubkiene L., Valentin L. Cesarean section scar defects: agreement between transvaginal sonographic findings with and without saline contrast enhancement. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010; 35(1): 75-83. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.7496.

- Буянова С.Н., Пучкова Н.В. Несостоятельный рубец на матке после кесарева сечения: диагностика, тактика ведения, репродуктивный прогноз. Российский вестник акушера-гинеколога. 2011; 11(4): 36-8. [Buyanova S.N., Puchkova N.V. Insufficient cesarean scar: diagnosis, management tactics, reproductive prognosis. Russian Bulletin of the Obstetrician-Gynecologist. 2011; 11(4): 36-8. (in Russian)].

- Краснопольская К.В., Попов А.А., Чечнева М.А., Федоров А.А., Ершова И.Ю. Прегравидарная метропластика по поводу несостоятельного рубца на матке после кесарева сечения: влияние на естественную фертильность и результаты ЭКО. Проблемы репродукции. 2015; 21(3): 56-62. [Krasnopolskaya K.V., Popov A.A., Chechneva M.A., Fedorov A.A.,Ershova I.Yu. Pregravid metroplasty for insolvent uterine scar after cesarean section: effects on natural fertility and IVF results. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2015; 21(3): 56-62. (in Russian)].

- Chen J., Cui H., Na Q., Zi Q., Zui C. Analysis of emergency obstetric hysterectomy: the change of indications and the application of intraoperative interventions. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2015; 50(3): 177-82.

Received 20.05.2020

Accepted 01.10.2020

About the Authors

Nadezhda Yu. Zemskova, Junior Researcher, Department of Ultrasound Diagnostics, Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology.Tel: +7(495)011-00-42. E-mail: fluimucil@yandex.ru. 101000, Russia, Moscow, Pokrovka str., 22a.

Marina A. Chechneva, Head of the Department of Ultrasound Diagnostics, Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Tel: +7(495)011-00-42. E-mail: marina-chechneva@yandex.ru. 101000, Russia, Moscow, Pokrovka str., 22a.

Vasiliy A. Petrukhin, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Director of the Moscow Regional Research Institute of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Tel: +7(495)011-00-42. E-mail: petruhin271058@mail.ru. 101000, Russia, Moscow, Pokrovka str., 22a.

Svetlana Yu. Lukashenko, engineer, PhD of physical and mathematical sciences, Scientific Research Institute for System Analysis of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Tel: +7(495)718-21-10. E-mail: s_lukashenko@mail.ru. 117218, Russia, Moscow, Nakhimovskiy prospekt, 36-1.

For citation: Zemskova N.Yu., Chechneva M.A., Petrukhin V.A., Lukashenko S.Yu. Ultrasound examination of the cesarean scar in the prognosis of pregnancy outcome.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya / Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020; 10: 99-104 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.10.99-104