The role of preeclampsia in pregnancy outcomes: the view of a neonatologist

Objective. To analyze the health status of infants born to mothers with preeclampsia and the course of their early neonatal period.Timofeeva L.A., Karavaeva A.L., Zubkov V.V., Kirtbaya A.R., Kan N.E., Tyutyunnik V.L.

Material and methods. The study analyzed perinatal outcomes in 525 mother-newborn pairs, who were divided into two groups. Group 1 included 160 infants born to mothers with preeclampsia; group 2 comprised 365 infants born to mothers with normal pregnancies. The analysis involved women’s medical history, the course of pregnancy, childbirth, delivery mode, and the course of the early neonatal period of newborns.

Results. The study findings showed that infants born to mothers with preeclampsia are more likely to have congenital developmental anomalies, genetic and metabolic disorders, and a higher risk of infectious and hematological diseases.

Conclusion. The severity of newborns’ condition, the risk of neonatal complications, the severity of infectious processes, and hypoxic-ischemic conditions has a direct correlation with the timing and severity of preeclampsia.

Keywords

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy complication associated with many predisposing factors, including high blood pressure, metabolic disorders, multiple pregnancies, late reproductive age, cardiovascular disease, body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2, assisted reproductive technologies, a history of preeclampsia in prior pregnancy [1-4]. Currently, this complication is one of the most significant medical and social issues worldwide and remains one of the leading causes of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality [2, 3, 5, 6].

According to the current international literature, pre-eclampsia affects about 6-10% of all pregnancies [7, 8]; in Russia, this figure is 3-7% [9, 10]. It is well known that preeclampsia during pregnancy is accompanied by a high preterm birth rate (10-12%) [7-9]. According to WHO, more than 15 million premature babies are born annually to mothers, whose pregnancies are complicated by preeclampsia [11].

According to both domestic and international literature, infants whose mothers had preeclampsia are also at increased risk for metabolic disorders, which subsequently lead to the development of various complications. Also, there is a higher risk of developing respiratory, hematological disorders (anemia, polycythemia and thrombocytopenia of the newborn), intracranial hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, aggravation of infectious diseases, which creates prerequisites for a longer observation of the child, both in the hospital and upon discharge to home [12, 13].

As seen from the above data, investigating the effect of preeclampsia on neonatal outcomes remains relevant to the present day and requires careful analysis to reduce neonatal morbidity.

This study aimed to analyze the health status of infants born to mothers with preeclampsia and the course of their early neonatal period.

Material and methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of medical records of 525 mother-newborn pairs treated at the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia between 2013 and 2016. Group 1 (study group) comprised 160 infants born to mothers with preeclampsia (48 of them had early (before 34 weeks) and 112 late preeclampsia (after 34 weeks); group 2 (control group) included 365 infants born to mothers with normal pregnancies.

The inclusion criteria for the study patient selection were as follows: singleton pregnancy with clinical manifestation of preeclampsia for group 1 and an uncomplicated pregnancy group 2. All women provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: severe non-obstetric pathology (oncological diseases, severe complicated course, a history of organ transplantation, severe autoimmune diseases, diabetes mellitus, maternal cardiovascular disease), hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn, multiple pregnancies.

At baseline, we analyzed women’s medical history, the course of pregnancy, childbirth, delivery mode, and the course of the early neonatal period of newborns. Neonatal well-being immediately after birth was evaluated using the Apgar score at the first and the fifth minute; growth parameters of full-term newborns were assessed using percentile charts. For preterm infants with gestational ages of less than 37 weeks, T.R. Fenton (2013) preterm growth charts were used. Neuromuscular and physical maturity was measured using the Ballard Scale (1979).

Clinical evaluation of newborns depended on their clinical condition and consisted of laboratory testing, including the complete blood count and blood chemistry tests, C-reactive protein, urinalysis; diagnostic investigations (according to indications) included ultrasound, echocardiography, chest and abdominal radiography.

All the results were entered into specially developed thematic cards and MS Excel spreadsheets. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Statistics 17.0 for Windows software package. When assessing the statistical significance of the differences between the mean values of the samples and the reliability of the correlation detected, the probability of error p was calculated. According to generally accepted terminology in analytical statistics, statements that have an error probability of p ≤ 0.05 are called significant; the statements with the error probability p ≤ 0.01 are very significant, and the statements with the error probability p ≤ 0.001 are the most significant.

Results and discussion

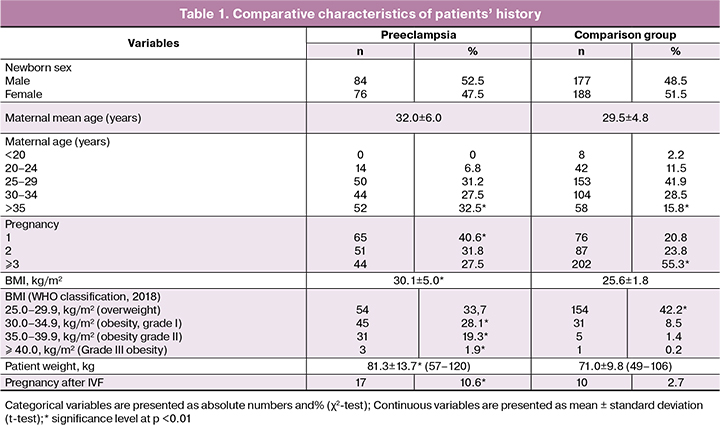

At the first stage, data on the patients’ history have been collected and analyzed; the results are presented in Table 1.

Univariate analysis showed a significant relationship between a woman’s age and the risk of pre-eclampsia, which is consistent with some studies investigating the relationship between these factors [14]. However, previous studies suggested that the age older than 40 years is a risk factor for pre-eclampsia [14, 15]. In our study, significant differences were found in patients aged over 35 years.

The mean age of the women included in the study was 32.0 ± 6.0 and 29.5 ± 4.8 years (p = 0.01) in group 1 and 2, respectively. As a rule, in most cases, preeclampsia occurred in nulliparous women (group 1, n = 52 (32.5%), group 2, n = 58 (15.8%), p <0.001). The newborn sex was not associated with the increased risk of preeclampsia.

Studies conducted in the United States [16] reported that both obese (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2) and overweight women (BMI = 25.0-29.9 kg/m2) are at a significantly increased risk of developing preeclampsia; an increase in BMI by 5-7 kg/m2 above 30 kg/m2 almost doubles the risk of developing preeclampsia [17].

The analysis of anthropometric findings showed that at the onset of pregnancy, 83.1% of women with preeclampsia were overweight compared to 52.6% of women in the comparison group. Mean BMI in group 1 and 2 was 30.1 ± 13.7 kg/m² and 25.66 ± 1.8 kg/m², respectively (p <0.001). Excess BMI above 30 kg/m² was observed in 79 (49.4%) and 37 (10.1%) women in group 1 and 2, respectively (p <0.001). Overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9 kg / m²) was observed in 54 (33.7%) and 154 (42.2%) in group 1 and 2, respectively.

Therefore, the effect of overweight on the increased risk of developing pre-eclampsia has not been identified. However, it is noteworthy that we found significant differences (p <0.01) in patients with obesity I - III.

In recent decades, an additional risk factor for preeclampsia has been identified. According to ACOG, assisted reproductive technologies (especially with a donation of germ cells and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome) carry a substantial increase in the risk of preeclampsia [16, 18], which was also shown in our study. Pregnancies achieved by assisted reproductive technologies were found five times more often in group 1 (n = 17, 10.6%) than in group 2 (n = 10, 2.7%).

Besides, we found that the risk of preeclampsia is statistically significantly higher in patients with diseases of the cardiovascular system (39.2% and 2.7% in the groups, respectively) and with the kidneys and urinary tract diseases (52.5% and 20, 3%).

Taking into consideration the contradictory data on the rates and structure of pregnancy and childbirth complications associated with preeclampsia [3, 5, 19], we analyzed the course of pregnancy and labor.

Significant complications during pregnancy (p <0.05) included threatened preterm birth in the first trimester (n = 55; 34.4%) and (n = 87; 23.8%) in groups, respectively). In the second trimester, no significant differences were found. Complications occurring in the third trimester included fetal growth restriction (n = 11; 6.9% and n = 8; 2.2%), placental insufficiency (n = 12; 7.5% and n = 10; 2.7%), and oligohydramnios (n = 35; 21.9% and n = 32; 8.8%).

We have analyzed the features and timing of delivery in the groups, which are presented in table 2.

It is also noteworthy that the vast majority of women in group 1 (n = 130; 81.8%) required surgical delivery by cesarean section, while in group 2 this figure was 142 (38.9%). In group 1, the most often (50% of cases) indication for surgical delivery was an increasing severity of pre-eclampsia and/or fetal deterioration.

The mean term of delivery in pregnant women by pre-eclampsia was 36.6 ± 2.9 weeks and 39.1 ± 1.3 weeks in the control group. These data corresponded to lower anthropometric parameters of newborns in group 1 (p <0.01): the birth weight of newborns in group 1 and 2 was 2,730.8 ± 835.0 g and 3405.0 ± 488.9 g; body length 48.0 ± 5.2 cm and 51.7 ± 2.7 cm, respectively.

The need for early delivery due to the increasing severity of pre-eclampsia and fetal deterioration against the background of chronic intrauterine hypoxia is also linked to lower Apgar scores in newborns and high rates of moderate and severe birth asphyxia.

The first- and fifth-minute Apgar scores were significantly lower (p >0.01) in the newborns in group 1 (1-min Apgar scores in group 1 and 2 were 6.8 ± 1.2 and 7.9 ± 0; 5-min Apgar scores in group 1 and 2 were 8.1 ± 0.8 and 8.7 ± 0.5). The rate of moderate and severe fetal birth asphyxia in group 1 3.5-fold higher than in group 2 (n = 23, 14.4%) and (n = 15, 4.1%), respectively. It should be noted that the onset and severity of preeclampsia had a significant impact on these parameters, which is consistent with the literature [20]. So, we found that the incidence of preterm delivery in women with early and late preeclampsia was 89.6% (n = 43) and 32.1% (n = 35), respectively (p <0.01). This fact revealed statistically significant differences (p <0.01) in the rates of fetal birth asphyxia in women with early and late preeclampsia 60.4% (n = 29) and 20.5% (n = 23), respectively. Also, there were 2 (4.1%) antenatal fetal deaths in patients with early and severe preeclampsia.

There were almost 4 times more congenital malformations in group 1 (n = 29; 18.1%) than in group 2 (n = 17; 4.6%). Among the newborns in group 1, congenital heart defects (n= 9) included ventricular septal defect (n = 6), aortic coarctation (n = 2), and left ventricular hypoplasia (n = 1); the kidney and urinary tract birth defects (n = 14) comprised the kidney agenesia or hypoplasia (n = 4), hypospadias (n = 4), omphalocele (n = 2), genetic diseases (Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (n = 1), Carnelia De Lange syndrome (n = 1 ), and chromosome 21 trisomy syndrome (n = 2).

Among the newborns in group 2, congenital abnormalities included 2 cases of gastroschisis, 2 cases of agenesia of one kidney, and 2 cases of congenital heart disease (ventricular septal defect); the remaining malformations were small congenital anomalies.

In the structure of diseases in infants born to mothers with preeclampsia, respiratory diseases made up 9.4% (n = 29) compared with 1.9% (n = 7) in group 2 (p <0.01); 15.6% (n = 25) and 1.1% (n = 4) had hematological disorders, such as anemia and thrombocytopenia, respectively.

The congenital infection rate was higher in group 1, compared with group2 (p <0.01). The rate of congenital pneumonia was 15% (n = 24) and 2.5% (n = 9) in group 1and 2, respectively. Congenital sepsis (n = 5; 3.1%) and necrotizing enterocolitis (n = 3; 1.9%) were observed only in group 1.

Metabolic disorders of the early neonatal period (neonatal hypoglycemia, which required correction in the first hours after birth) were observed five times more often in group 1 than in group 2 (n = 15; 9.4% and n = 7; 1.9%, respectively).

Due to the severity of pathological changes and lower gestational age of the newborns in group 1, 39.6% of the children (n = 63) in that group required intensive observation and care in the neonatal intensive care units and the subsequent transfer to the second stage of nursing (in the control group n = 30 ; 8.3%). The length of hospital stay was significantly longer in newborns in group 1 (p <0.01) averaging 12.7 ± 13.5 days compared with 6.4 ± 4.6 days in group 2.

The current literature is lacking studies investigating the association of gestational age and neonatal morbidity in preeclampsia [21], and this suggests a need for further study to explore this association.

The study findings showed that pre-eclampsia has a negative impact on the condition of the fetus and newborn. From 11 to 20% of induced preterm labors are associated with the occurrence of this complication. At the same time, most of the newborns require highly qualified specialized neonatal care. The severity of newborns’ condition, the risk of neonatal complications, the severity of infectious processes, and hypoxic-ischemic conditions has a direct correlation with the timing and severity of preeclampsia.

Conclusion

The prognosis of neonatal morbidity and the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes are largely dependent on the timing of delivery. Therefore, the optimal obstetric management strategy for patients with preeclampsia should be based on a qualitative assessment of maternal and fetal risks. Improving the quality of medical care for pregnant women with severe obstetric complications, including preeclampsia, and providing highly specialized neonatal care remains the utmost priority for maternal institutions at all stages of obstetric care.

References

- Сухих Г.Т., Ходжаева З.С., Филиппов О.С., Адамян Л.В., Краснопольский В.И., Серов В.Н., Сидорова И.С., Баев О.Р., Башмакова Н.В., Кан Н.Е.,Клименченко Н.И., Макаров О.В., Никитина Н.А., Петрухин В.А., Пырегов А.В., Рунихина Н.К., Тетруашвили Н.К., Тютюнник В.Л., Холин А.М., Шмаков Р.Г., Шешко Е.Л. Федеральные клинические рекомендации. Гипертензивные расстройства во время беременности, в родах и послеродовом периоде. Преэклампсия. Эклампсия. М.: Российское общество акушеров-гинекологов; 2013. [Sukhikh G.T., Serov V.N., Adamyan L.V., Filippov O.S., Bashmakova N.V., Baev O.R., Kan N.E., Klimenchenko N.I., Makarov O.V., Nikitina N.A., Petruhin V.A., Pyregov A.V., Runihina N.K., Sidorova I.S., Tetruashvili N.K., Tyutyunnik V.L., Khodzhaeva Z.S., Holin A.M., Shmakov R.G., Sheshko E.L. Federal clinical guidelines. Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, during childbirth and the postpartum period. Pre-eclampsia. Eclampsia. M .: Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013. (in Russian)].

- Paré E., Parry S., McElrath T.F., Pucci D., Newton A., Lim K.H. Clinical risk factors for preeclampsia in the 21st century. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014; 124(4): 763-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000451.

- Shamshirsaz A.A., Paidas M., Krikun G. Preeclampsia, hypoxia, thrombosis, and inflammation. J. Pregnancy. 2012; 2012: 374047. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/374047.

- Blencowe H., Cousens S., Oestergaard M.Z., Chou D., Moller A.B., Narwal R. et al. National, regional, and estimates of preterm birth rates in the 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries^ a systematic analisis and implications. Lancet. 2012; 379(9832): 2162-72. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4.

- Vikse B.E., Irgens L.M., Leivestad T., Skjaerven R., Iversen B.M. Preeclampsia and the risk of end-stage renal disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008; 359(8): 800-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0706790.

- Cornelius D.C. Preeclampsia: From inflammation to immunregulation. Clin. Med. Insights Blood Disord. 2018; 11: 1179545X17752325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179545X17752325. eCollection 2018.

- WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. WHO; 2011.

- Ukah V., De Silva D.A., Payne B. Prediction of adverse maternal outcomes from pre-eclampsia and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A systematic review. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017; 11: 115-23. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2017.11.006.

- Ходжаева З.С., Коган Е.А., Клименченко Н.И., Акатьева А.С., Сафонова А.Д., Холин А.М., Вавина О.В., Сухих Г.Т. Клинико-патогенетические особенности ранней и поздней преэклампсии. Акушерство и гинекология. 2015; 1: 12-7. [Hodzhaeva ZS, Kogan EA, Klimenchenko NI, Аkat’eva АS, Safonova АD, Kholin АM, Vavina OV, Sukhikh GT. Clinical and pathogenetic features of early and late preeclampsia. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 2015; 1: 12-17. (in Russian)].

- Какорин Е.П., Стародубов В.И., ред. Основные показатели здоровья матери и ребенка, деятельность службы охраны детства и родовспоможения в Российской Федерации. М.: Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации, Департамент мониторинга, анализа и стратегического развития здравоохранения, ФГБУ «Центральный научно-исследовательский институт организации и информатизации здравоохранения» Минздрава Российской Федерации; 2018. [Kakorin E.P., Starodubov V.I. ed. The main indicators of maternal and child health, the activities of the service of the protection of children and obstetric aid in the Russian Federation. M .: Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Department of Monitoring, Analysis and Strategic Development of Health, Federal State Budgetary Institution «Central Research Institute for Organization and Informatization of Health» of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation; 2018.(in Russian)].

- Liem S., Schuit E., Hegeman M., Bais J., de Boer K., Bloemenkamp K. et al. Cervical pessaries for prevention of preterm birth in women with a multiple pregnancy (ProTWIN): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013; 382(9901): 1341-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61408-7.

- Backes C.H., Markham K., Moorehead P., Cordero L., Nankervis C.A., Giannone P.J. Maternal preeclampsia and neonatal outcomes. J. Pregnancy. 2011; 2011: 214365. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/214365.

- Ton T.G., Bennett M., Incerti D., Peneva D., Druzin M., Stevens W. et al. Maternal and infant adverse outcomes associated with mild and severe preeclampsia during the first year after delivery in the United States. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019; Feb.19. https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1679916.

- Roos N., Kieler H., Sahlin L., Ekman-Ordeberg G, Falconer H., Stephansson O. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011; 343: d6309. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d6309.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in pregnancy. NICE clinical guideline 107. London: RCOG Press; 2011.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 671: Perinatal risks associated with assisted reproductive technology. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 128(3): e61-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001643.

- Стародубов В.И., Суханова Л.П. Репродуктивные проблемы демографического развития России. М.: Менеджер здравоохранения; 2012: 53-5. [Starodubov V.I., Sukhanova L.P. Reproductive problems of the demographic development of Russia. M .: Health Manager; 2012: 53-5. (in Russian)].

- Redman C.W., Sargent I.L. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005; 308(5728): 1592-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1111726.

- Aslam H.M., Saleem S., Afzal R., Iqbal U., Saleem S.M., Shaikh M.W.A., Shahid N. Risk factors of birth asphyxia. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014; 40: 94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13052-014-0094-2.

- Gruslin A., Lemyre B. Pre-eclampsia: Fetal assessment and neonatal outcomes. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011; 25(4): 491-507. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.02.004.

- Hassan M., Begum M., Haque S.M.Z., Jahan N., Yasmeen B.H.N., Mannan A. et al. Immediate outcome of neonates with maternal hypertensive disorder of pregnancy at a neonatal intensive care unit. North. Int. Med. Coll. J. 2015; 6(2): 57-60.

Received 15.09.2018

Accepted 21.09.2018

About the Authors

Timofeeva, Leila A., PhD, head of the Neonatal Unit, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of Minzdrav of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: +79252534444. E-mail: l_timofeeva@oparina4.ruKaravaeva, Anna L., clinical care supervisor at the Neonatal Unit, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology

of Minzdrav of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: +79262794639. E-mail: a_karavaeva@oparina4.ru

Zubkov, Victor V., MD, director of the Institute of Neonatology, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of Minzdrav

of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: +79637504877. E-mail: v_zubkov@oparina4.ru

Kirtbaya, Anna R., PhD, clinical care supervisor at the Neonatal ICU, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology

of Minzdrav of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel: +79637504877. E-mail: a_kirtbaya@oparina4.ru

Kan, Natalia E., MD, professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics,

Gynecology and Perinatology of Minzdrav of Russia.

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: +79262208655. E-mail: kan-med@mail.ru. Number Researcher ID B-2370-2015. ORCID ID 0000-0001-5087-5946

Tyutyunnik, Victor L., MD, professor, head of the Obstetric Physiological Department, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics,

Gynecology and Perinatology of Minzdrav of Russia.

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: +79039695041. E-mail: tioutiounnik@mail.ru. Number Researcher ID B-2364-2015.ORCID ID 0000-0002-5830-5099

For citation: Timofeeva L.A., Karavaeva A.L., Zubkov V.V., Kirtbaya A.R., Kan N.E., Tyutyunnik V.L. The role of preeclampsia in pregnancy outcomes: the view of a neonatologist. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; (4): 73-8. (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.4.73-78