Delivery in premature rupture of membranes at 22 to 28 weeks: management tactics, perinatal outcomes

Objective: To assess the pregnancy course and perinatal outcomes in pregnant women with premature rupture of membranes at 22 to 28 weeks using wait-and-see management.Kuznetsova N.B., Dybova V.S.

Materials and methods: The investigation was prospective. It enrolled 30 female patients with premature rupture of membranes at 22–28 weeks’ gestation. All the pregnant women with amniorrhea underwent a standard examination and a vaginal microbiome study using the special gene technology – 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Results: Wait-and-see tactics with an increase in the gestational period led to the birth of babies with a larger weight and a better Apgar score at one and five minutes. However, the development of an inflammatory reaction in a pregnant woman increased the risk of chorioamnionitis and neonatal sepsis. An analysis of vaginal microbiome in pregnant women showed that the presence of bacteria of the Ureaplasma genus was associated with low birth weight, an increase in the relative abundance (%) of these bacteria was related to low neonatal survival rates in the first 7 days, and the presence of Dialister bacteria was linked to the development of chorioamnionitis.

Conclusion: Prolongation of pregnancy when choosing a wait-and-see management tactic, by increasing the duration of the time between membrane rupture and delivery in premature rupture of membranes at 22 and 28 weeks’ gestation and, accordingly, the gestational period at the time of delivery is associated with an improvement in perinatal outcomes. The appearance of signs of a systemic inflammatory response, the presence of Ureaplasma and Dialister bacteria, and an increase in the relative abundance (%) of Ureaplasma bacteria in the vaginal microbiome is a risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes.

Keywords

The rate of extremely preterm birth and delivery before 28 weeks’ gestation is about 5% of all preterm births [1].

Babies born between 22 and 28 weeks of gestation usually have an extremely low birth weight (less than 1000 g) and very unfavorable prognoses, a high percentage of perinatal and neonatal deaths, bronchopulmonary diseases, and disability [2].

Preterm labor begins with premature rupture of membranes (PROM) in 30% of cases; some authors even propose to single out PROM as a separate entity of preterm birth. PROM is the leakage of amniotic fluid before the onset of labor, which is especially dangerous before 28 weeks. Membrane containment damage and amniorrhea will inevitably lead to spontaneous or induced preterm births. It is only a matter of time. The task for practical obstetrics is to determine what tactics should be chosen and what influences the choice of tactics and the timing of delivery in pregnant women with PROM before 28 weeks of pregnancy. This may be one of the most questions under discussion in perinatology in the 21st century.

Both the pathogenesis of membrane rupture and subsequent maternal and neonatal complications are closely related to an infectious and inflammatory factor. Vaginal pathogenic or opportunistic bacterial colonization is assumed to activate the local (the cervical canal and membranes) immune system, by setting in motion a cascade of inflammatory reactions, which in turn causes the disrupted structure of the membranes and their premature rupture. Many attempts have been made to find associations between certain genera, species of bacteria that inhabit the vagina, and pregnancy complications. A significant breakthrough in our understanding of the microbiocenosis of the genitourinary tract became possible owing to the International Human Microbiome Project, which has allowed one to take a fresh look at the role of microorganisms in human physiology and pathology, in preterm birth in particular [1, 3]; the concept of microbiome has evolved. The latest sequencing technologies have made it possible to expand our knowledge about the microbiota of the female reproductive system, placenta, and fetus and continue to develop rapidly.

Objective: To assess the pregnancy course and perinatal outcomes in women with PROM at 22 to 28 weeks, by using the wait-and-see management tactic.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at the the Perinatal Center, Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, from 1, 2019 to March 31, 2021. It enrolled 30 women with PROM at 22 to 28 weeks’ gestation.

The inclusion criteria were an age of 18 to 40 years; the Caucasian race. The exclusion criteria were a pregnancy conceived with assisted reproductive technologies, multiple pregnancy, hydramnios, cervical surgery, congenital uterine malformations, fetal malformations, the presence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, severe extragenital pathology, gestational diabetes mellitus, antibiotic therapy during pregnancy before included until the women were included in the study, invasive treatment and diagnostic techniques (amniocentesis, amnioreduction), trauma during pregnancy, and bad habits (smoking, alcoholism).

Upon admission of the patients to the Perinatal Center, diagnostic and therapeutic measures were implemented in accordance with Russian Federation (RF) Ministry of Health Order No. 572n “On Approval of a Procedure for Providing Medical Care in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Profile (except for the use of assisted reproductive technologies)” dated November 1, 2012 [4], valid at the time of the study (since January 1, 2021, in accordance with RF Ministry of Health Order No. 1130n “On Approval of the Procedure for Providing Medical Care in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Profile” dated October 20, 2020 [5]; management was done using the 2013 current clinical practice guidelines “Premature Birth” (treatment protocol) [6] (revised in 2020 [7]), in accordance with Russian Ministry of Health Order No. 203n “On Approval of Criteria for Assessing the Quality of Medical Care” [8] dated May 10, 2017. In all cases, the wait-to-see management tactic was used according to the clinical practice guidelines when following up pregnant women with PROM at 22 to 28 weeks’ gestation. To assess the outcomes, we analyzed gestational age at birth, fetal maturity and weight, a newborn’s stusus, by using the Apgar scale, the incidence of neonatal sepsis, and pediatric intensive care unit length (days) of stay. The primary endpoint of the study was survival rates for babies within 7 days after their birth.

According to the current practice guidelines “Premature Birth” (treatment protocols) [6, 7], all the patients underwent bacteriological analysis of their cervical canal discharge, by determining the sensitivity of a pathogen to antibiotics and other drugs, as well as a microscopic examination of female genital discharge; they were also prescribed antibiotic therapy to maximize the prolongation of pregnancy. To determine the vaginal bacterial composition in pregnant women with PROM, a microbiome study was conducted using 16S rRNA gene sequencing technology. Materials for the microbiome study were taken from the posterior vaginal vault in the first 12 hours after amniotic fluid discharge, before initiating antibiotic therapy at 22 to 28 weeks’ gestation.

The samples were placed into the sterile test tubes containing a transport medium and a mucolytic agent (Central Research Institute of Epidemiology, Russia) and stored at +4°С until DNA was isolated. The vaginal microbiome composition was determined in the Serbalab laboratory (Saint Petersburg).

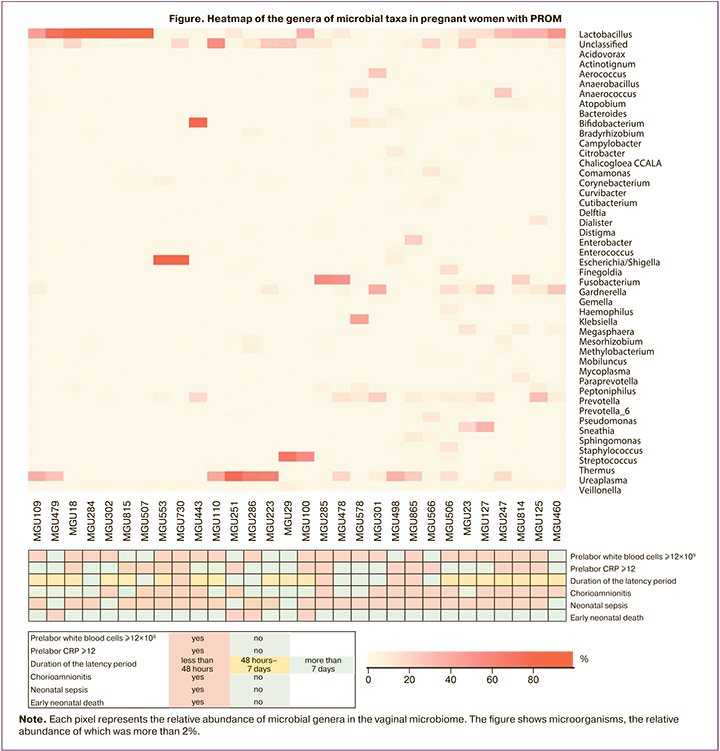

The vaginal microbiome composition in the pregnant women of both groups was studied according to the generally accepted taxonomic classification by ranks: type, class, order, family, genus, and species. There were 30 types, 43 classes, 150 families, 309 genera, and 486 species. Previously, we comparatively assessed the vaginal microbiome in women with PROM at 22 to 28 weeks of pregnancy and with the physiological course of pregnancy at the same time [9]. This paper analyzes the results of the vaginal microbiome study in pregnant women with PROM at 22 to 28 weeks’ gestation and the relationship to perinatal outcomes, by comparing of the frequency of a bacterial agent and the proportion of each microorganism in the vaginal microbiome, which was expressed as percentages. To describe the shares, the term “relative abundance” was used, which is translated as "relative intensity". The analysis involved microorganisms with a relative abundance of more than 2%.

Statistical analysis

The findings were statistically processed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 23 application software package. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistical tests and the equality of variances in the compared groups (homoscedasticity) were used to test the hypothesis that the test sample obeyed the normal distribution law. For the description of quantitative data having a normal distribution, we applied the arithmetic mean (M) and standard deviation (SD); medians (Me) and interquartile intervals (Q1; Q3) for non-normal distributions. The number of observations of the trait, their total number, and their percentage were indicated when describing the frequencies of qualitative indicators.

The main study was conducted in one group. Correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship (association) of two signs. When conducting a correlation analysis, we employed the Pearson coefficient (where the sample obeyed the normal distribution law, the correlation coefficient was denoted as r) and Spearman’s coefficient (where the sample did not obey the normal distribution law, the correlation coefficient was denoted as rs).

Nonparametric statistical methods (Fisher’s exact test, Pearson’s classical chi-square test) were used to compare the sets by qualitative characteristics. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test was applied to compare the sets by quantitative characteristics, considering the absence of a normal distribution. The sample size was sufficient to ensure a power of at least 80% for the statistical tests, when compared.

The relative risks of adverse outcomes were calculated with the contingency tables.

The generally accepted statistical significance levels of p<0.05 were used.

Results

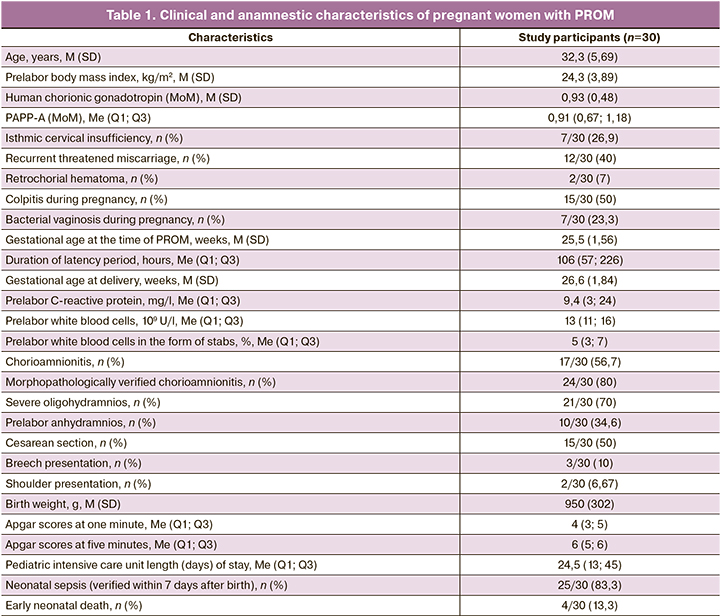

The study involved 30 Caucasian women aged 18 to 40 years with PROM at 22 to 28 weeks’ gestation who met the study criteria. The clinical and anamnestic characteristics of pregnant women with PROM are given in Table 1.

The gestational age at the time of PROM and inclusion in the study was 25.5 (1.56) weeks. The study involved only patients whose duration of PROM did not exceed 12 hours at the time of examination. The diagnosis of PROM was established by visual confirmation of fluid leakage from the cervical canal during speculum examination using a cough stress test, as well as during a positive amniotest and/or a positive AmniSure test. Ultrasound amniotic fluid index measurement must be necessarily done.

The management tactics was aimed at the longest possible prolongation of pregnancy prior to the development of regular labor activity in 10/30 (33.3%) women, to the emergence of severe oligohydramnios for three days or anhydramnios in 12/30 (40%), and to the appearance of signs of chorioamnionitis in 6/30 (20%). The indications for delivery were placental detachment in 1/30 (3.33%) of the women and umbilical cord loop prolapse in 1/30 (3.33%).

The duration of the latency period was 106 (57; 226) hours, varying from 0.45 to 910 hours. The latency of less than two days (48 hours or less) was seen in 4/30 women; that of 2–7 days (72–168 hours) was in 18/30 women; that of more than 7 days (more than 168 hours in 8/30.

Clinical blood analysis (white blood cells, differential blood count) and blood C-reactive protein were monitored in all the patients. The prelabor level of white blood cells was 13 (11; 16)×109 U/l; that of white blood cells in the form of stabs was 5 (3; 7)%; and that of C-reactive protein was 9.4 (3; 24) mg/l.

The gestational age at delivery was 26.6 (1.84) weeks. The surgical delivery rate was 50% (15/30 women). The indications for surgical delivery in women with PROM were: severe oligohydramnios for three days or anhydramnios, irregular labor activity; fetal breech presentation, less often a uterine scar after cesarean section, placental presentation and detachment, and umbilical cord loop prolapse.

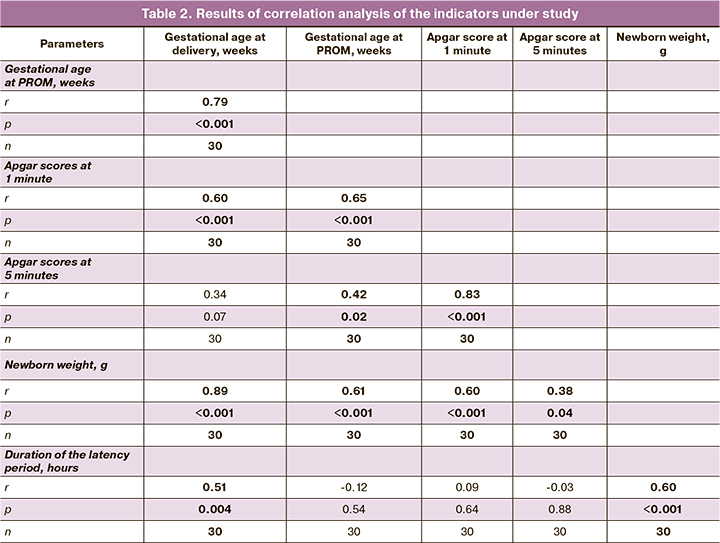

The birth weight of babies was 950 (302) g. The longer latency period (measured in hours) during prolonged pregnancy (r=0.60 (0.30–0.79); p<0.001), as well as the longer gestational age at delivery (r=0.89 (0.78–0.95), p<0.001) was associated with neonatal weight gain.

The status of a newborn infant is further evidence for the positive impact of prolonged pregnancy. The neonatal status was assessed using the Apgar scale. The Apgar scores at 1 and and 5 minutes were 4 (3; 5) and 6 (5; 6), respectively. It was noted that the longer the gestational age was at the time pf PROM, the higher the newborn Apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes were (rs=0.65 (0.37–0.82) at p<0.001 and rs=0.42 (0.07–0.68) at p=0.02, respectively). Also, the longer the gestational age was at delivery, the higher the Apgar scores at 1 minute (rs = 0.60 (0.30–0.79) at p<0.001). Similarly, the higher the birth weight of a baby, the higher the Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes (r=0.60 (0.30-0.79), p<0.001 and r=0.38 (0.20–0.65), p=0.04). The findings suggest that the longer duration of pregnancy in the cases under study was associated with the higher weight of a baby and milder birth asphyxia (Table 2).

Characterizing perinatal outcomes in babies born to mothers with PROM, we assessed gestational age at the time of membrane rupture and at delivery, its method, duration of the latency period, amniotic fluid index, C-reactive protein, white blood cells, white blood cells in the form of stabs prior to delivery, vaginal microbiome in pregnant women, newborn weight, Apgar scores for asphyxia, incidence of chorioamnionitis, neonatal sepsis, pediatric intensive care unit length (days) of stay, and neonatal survival in the first 7 days of life.

The factors associated with adverse perinatal outcomes were white blood cell and C-reactive protein levels before delivery, as well as bacteria of the genera Ureaplasma and Dialister in the vaginal microbiome.

The increase in the level of C-reactive protein ≥12 mg/l prior to delivery was related to the development of chorioamnionitis (OR=2.1, 95% CI: [1.14; 5.71], p=0.03): the patients with a C-reactive protein level of ≥12 mg/l developed chorioamnionitis in 11/14 cases; those with a C-reactive protein level of <12 mg/l did in 6/16 cases. With a rise in prelabor white blood counts of ≥12×109, the risk of neonatal sepsis increased by 1.71 times (OR=1.71, 95% CI: [1.07; 4.29], p=0.02): the patients with prelabor white blood counts of ≥12×109 and <12×109 were observed to have neonatal sepsis in 20/21 and 5/9 cases, respectively.

Vaginal microbiome analysis showed that the pregnant women with Ureaplasma bacteria had lower birth weight babies: 865 g (n=307), 1096 g (n=238) (p=0.02) than those without bacteria of this genus in the vaginal microbiome. The pregnant women with Dialister bacteria, unlike those with no bacteria of this genus, more frequently developed chorioamnionitis (OR=2.7, 95% CI: [1.24; 5.94], p=0.02): those with and without Dialister bacteria developed chorioamnionitis in 14/19 and 3/11 cases, respectively. It was also found that the relative abundance (%) of bacteria of the genus Ureaplasma was higher [44.5 (13.3; 68.8)] in the pregnant women with PROM whose babies had died compared to the pregnant women whose babies survived for 7 days after birth [0.28 (0; 16.3)] (p=0.03) (Figure).

Analyzing the relative abundance (%) and the presence of other genera of microorganisms in the vaginal microbiome, including bacteria of the Lactobacillus genus, revealed no statistically significant associations with adverse perinatal outcomes. Analysis of gestational age at the time of PROM and at delivery, its method, duration of the latency period, and amniotic fluid index found no significant associations with the grade of asphyxia, incidence of chorioamnionitis, neonatal sepsis, pediatric intensive care unit length (days) of stay, and neonatal deaths.

Discussion

The relationship between neonatal sepsis and the duration of the latency period was first described in 1963 [10], chorioamnionitis and oligohydramnios after wait-to-see management for PROM have long been the main causes of fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality [11]. However, recent studies [2, 12–14], as well as our analysis, have provided contradictory evidence for this relationship.

J.H. Park et al. have shown that a long latent period (seven days or more), although slightly increases the risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, but, as in our study, does not affect survival in the neonatal period [12]. In the univariate analysis carried out by D. Drassinower et al., the newborns born to pregnant women with PPROM at 24 and 32 weeks in the group with a latency period of more than four weeks were less likely to have neonatal sepsis than those born to pregnant women with a latency period of less than four weeks (6.8% versus 17.2%; OR=0.40, 95% CI: [0.24; 0.66]) [13].

D.M. Bond et al. have made a meta-analysis published in the Cochrane Database Syst Rev in 2017, which indicates no difference in infant sepsis or mortality between the early delivery and long latency groups in the presence of PROM at 25 to 37 weeks’ gestation. But the early delivery increases a risk for infant death after birth, as well as that for breathing problems, as the newborns require additional medical care and are more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. The women randomized to the early delivery group had a higher incidence of labor induction, caesarean section, and uterine mucosal inflammation, but a lower risk of membrane infection and a shorter overall length of hospital stay [14].

Previous studies have also shown that chorioamnionitis, characterized by maternal fever, leukocytosis, tachycardia, uterine tenderness, plays an important role in the morbidity of premature infants. The consequences of chorioamnionitis affect many organ systems in the fetus and newborn, leading to conditions, such as cerebral palsy, retinopathy of prematurity, kidney and lung damage [15]. Our study has not confirmed chorioamnionitis to be an isolated factor of adverse perinatal outcomes, but it has found that leukocytosis (12×109 U/l or more) in a pregnant woman before delivery and elevated C-reactive protein levels are associated with the development of chorioamnionitis and neonatal sepsis. Of particular importance in this context is the infectious factor and inflammation, which are often the first cause of both rupture of membranes and subsequent complications [16–20]. According to our study, bacteria of the genera Ureaplasma and Dialister were of importance. The significance of the identified microorganisms has been confirmed by the results of other studies in both in PROM and in other pathological conditions [21–25].

Conclusion

Thus, based on the findings, we can say that wait-to-see management is associated with favorable perinatal outcomes (neonatal weight gain, reduced birth asphyxia). The risk of developing adverse perinatal outcomes in children born to women with PROM at 22 to 28 weeks’ gestation is associated with the appearance of signs of a systemic inflammatory response, as well as with the presence of bacteria of the genera Dialister and Ureaplasma and with an increase in the relative abundance (%) of bacteria of the genus Ureaplasma in the female vaginal microbiome.

References

- NIH Human Microbiome Portfolio Analysis Team. A review of 10 years of human microbiome research activities at the US National Institutes of Health, Fiscal Years 2007-2016. Microbiome. 2019; 7(1): 31.https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0620-y.

- Toukam M., Luisin M., Chevreau J., Lanta-Delmas S., Gondry J., Tourneux P. A predictive neonatal mortality score for women with premature rupture of membranes after 22–27 weeks of gestation. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019; 32(2): 258-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1378327.

- Brown R.G., Marchesi J.R., Lee Y.S., Smith A., Lehne B., Kindinger L.M. et al. Vaginal dysbiosis increases risk of preterm fetal membrane rupture, neonatal sepsis and is exacerbated by erythromycin. BMC Med. 2018; 16(1): 9.https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0999-x.

- Приказ Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 1 ноября 2012 г. № 572н «Об утверждении Порядка оказания медицинской помощи по профилю “акушерство и гинекология (за исключением использования вспомогательных репродуктивных технологий)”». https://minzdrav.gov.ru/documents/9154-prikaz- [Russian Federation Ministry of Health Order No. 572n “On Approval of a Procedure for Providing Medical Care in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Profile (except for the use of assisted reproductive technologies)” dated November 1, 2012. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://minzdrav.gov.ru/documents/9154-prikaz-

- Приказ Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 20.10.2020 № 1130н «Об утверждении порядка оказания медицинской помощи по профилю “акушерство и гинекология”». https://docs.cntd.ru/document/566162019 [Russian Federation Ministry of Health Order No. 1130n “On Approval of the Procedure for Providing Medical Care in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Profile” dated October 20, 2020. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/566162019

- Письмо Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 17.12.2013 №15-4/10/2-9480 «О направлении клинических рекомендаций (протокола лечения) “Преждевременные роды”». https://docs.cntd.ru/document/456011385 [Russian Federation Ministry of Health Letter No. 15-4/10/2-9480 “On the Area of the Clinical Practice Guidelines “Premature Birth” (Treatment Protocol) dated December 17, 2013.(in Russian)]. Available at: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/456011385

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Преждевременные роды. М.: Российское общество акушеров-гинекологов» (РОАГ), Ассоциация акушерских анестезиологов-реаниматологов (АААР); 2020. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical Practice Guidelines “Premature Birth”. M.: Russian Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RAOG), Association of Obstetric Anesthesiologists and Resuscitators (AOAR); 2020. (in Russian)].

- Приказ Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 10.05.2017 № 203н «Об утверждении критериев оценки качества медицинской помощи». https://docs.cntd.ru/document/436733768?marker=6560IO [Russian Federation Ministry of Health Order No. 203n “On Approval of Criteria for Assessing the Quality of Medical Care” dated May 10, 2017. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/436733768?marker=6560IO

- Кузнецова Н.Б., Буштырева И.О., Дыбова В.С., Баринова В.В., Полев Д.Е., Асеев М.В., Дудурич В.В. Микробиом влагалища у беременных с преждевременным разрывом плодных оболочек в сроке от 22 до 28 недель беременности. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 1: 94-102. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.1.94-102. [Kuznetsova N.B., Bushtyreva I.O., Dybova V.S., Barinova V.V., Polev D.E., Aseev M.V., Dudurich V.V. Vaginal microbiome in pregnant women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes at 22–28 weeks' gestation. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 1: 94-102 (in Russian).] https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.1.94-102.

- Pryles C.V., Steg N.L., Nair S., Gellis S.S., Tenney B. A controlled study of the influence on the newborn of prolonged premature rupture of the amniotic membranes and/or infection in the mother. Pediatrics. 1963; 31: 608-22.

- Kibel M., Asztalos E., Barrett J., Dunn M.S., Tward C., Pittini A. et al. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by pre-term premature rupture of membranes between 20 and 24 weeks of gestation. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 128(2): 313-20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001530.

- Park J.H., Bae J.G., Chang Y.S. Neonatal outcomes according to the latent period from membrane rupture to delivery among extremely preterm infants exposed to preterm premature rupture of membrane: a nationwide cohort study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021; 36(14): e93. https://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e93.

- Drassinower D., Friedman A.M., Običan S.G., Levin H., Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Prolonged latency of preterm premature rupture of membranes and risk of neonatal sepsis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 214(6): 743.e1-6.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.031.

- Bond D.M., Middleton P., Levett K.M., Ham D.P. van der, Crowther C.A., Buchanan S.L. et al. Planned early birth versus expectant management for women with preterm prelabour rupture of membranes prior to 37 weeks' gestation for improving pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017; 3(3): CD004735. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004735.pub4.

- Galinsky R., Polglase G.R., Hooper S.B., Black M.J., Moss T.J. The consequences of chorioamnionitis: preterm birth and effects on development. J. Pregnancy. 2013; 2013(2): 412831. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/412831.

- Ходжаева З.С., Гусейнова Г.Э., Муравьева В.В., Донников А.Е., Мишина Н.Д., Припутневич Т.В. Характеристика микробиоты влагалища у беременных с досрочным преждевременным разрывом плодных оболочек. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 12: 66-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.12.66-74. [Khodzhaeva Z.S., Guseynova G.E., Muravjeva V.V., Donnikov A.E., Priputnevich T.V. Characteristics of the vaginal microbiota in pregnant women with preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; 12: 66-74.(in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.12.66-74.

- Ходжаева З.С., Припутневич Т.В., Муравьева В.В., Гусейнова Г.Э., Горина К.А. Оценка состава и стабильности микробиоты влагалища у беременных в процессе динамического наблюдения. Акушерство и гинекология. 2019; 7: 30-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.7/30-38. [Khodzhaeva Z.S., Priputnevich T.V., Murav'eva V.V., Guseinova G.E., Gorina K.A., Mishina N.D. The composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota in pregnant women during dynamic observation. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; 7: 30-8 (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.7/30-38.

- Баринова В.В., Кузнецова Н.Б., Буштырева И.О., Соколова К.М., Полев Д.Е., Дудурич В.В. Микробиом верхних отделов женской репродуктивной системы. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 3: 12-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.12-17. [[Barinova V.V., Kuznetsova N.B., Bushtyreva I.O., Sokolova K.M., Polev D.E., Dudurich V.V. The microbiome of the upper female reproductive tract. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; 3: 12-17. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.12-17.

- Brown R.G., Marchesi J.R., Lee Y.S., Smith A., Lehne B., Kindinger L.M. et al. Vaginal dysbiosis increases risk of preterm fetal membrane rupture, neonatal sepsis and is exacerbated by erythromycin. BMC Med. 2018; 16(1): 9.https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0999-x.

- Cousens S., Blencowe H., Gravett M., Lawn J.E. Antibiotics for pre-term pre-labour rupture of membranes: prevention of neonatal deaths due to complications of pre-term birth and infection. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2010; 39(Suppl. 1): i134-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq030.

- Kacerovský M., Boudys L. Predcasný odtok plodové vody a Ureaplasma urealyticum [Preterm premature rupture of membranes and Ureaplasma urealyticum]. Ceska Gynekol. 2008; 73(3): 154-9.

- Kwak D.W., Hwang H.S., Kwon J.Y., Park Y.W., Kim Y.H. Co-infection with vaginal Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis increases adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of membranes. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014; 27(4): 333-7.https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2013.818124.

- Oh K.J., Romero R., Park J.Y., Hong J.S., Yoon B.H. The earlier the gestational age, the greater the intensity of the intra-amniotic inflammatory response in women with preterm premature rupture of membranes and amniotic fluid infection by Ureaplasma species. J. Perinat. Med. 2019; 47(5): 516-27.https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2019-0003.

- Brown R.G., Al-Memar M., Marchesi J.R., Lee Y.S., Smith A., Chan D. et al. Establishment of vaginal microbiota composition in early pregnancy and its association with subsequent preterm prelabor rupture of the fetal membranes. Transl. Res. 2019; 207: 30-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2018.12.005.

- Kosti I., Lyalina S., Pollard K.S., Butte A.J., Sirota M. Meta-analysis of vaginal microbiome data provides new insights into preterm birth. Front. Microbiol. 2020; 11: 476. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00476.

Received 06.07.2022

Accepted 13.10.2022

About the Authors

Natalia B. Kuznetsova, MD, Professor, Simulation Training Centre, Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(928)770-97-62, lauranb@inbox.ru,29 Nakhichevansky Lane, Rostov-on-Don, 344022, Russia.

Violetta S. Dybova, Postgraduate Student, Rostov State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia; Obstetrician/Gynecologist, Perinatal Center, Rostov-on-Don, +7(961)272-04-12, viola-kovaleva@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2391-8952, 29 Nakhichevansky Lane, Rostov-on-Don, 344022, Russia.

Authors’ contributions: Kuznetsova N.B. – the concept and design of the investigation, editing; Dybova V.S. – material collection and processing, statistical data processing; Dybova V.S., Kuznetsova N.B. – writing the text.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The source of funding is the Fund for Assistance to the Development of Small Forms of Enterprises in the Scientific and Technical Sphere (the Fund for Assistance to Innovations), the UMNIK program.

Ethical Approval: The Local Ethics Committee, Rostov State Medical University, has approved this investigation (Meeting Minutes No. 16/18 dated October 18, 2018).

Patient Consent to Publication: Each female participant has signed an informed consent form to the publication of her data.

Authors’ Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Kuznetsova N.B., Dybova V.S.

Delivery in premature rupture of membranes at 22 to 28 weeks:

management tactics, perinatal outcomes.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 11: 67-74 (in Russian)

http://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.11.67-74