Post-COVID-19 syndrome in early reproductive age women

Objective: To compare the incidence and severity of new persistent symptoms in young, somatically healthy women after novel coronavirus infection (NCI) with those who did not become ill during the pandemic. Materials and methods: To assess the independent impact of COVID-19 on the development of post-COVID syndrome (PCS), this study included non-pregnant women under 35 years of age, without excess body weight/obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic arterial hypertension, and other somatic and chronic infectious diseases. The study group included patients who recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection between July and October 2021, as confirmed by PCR (n=181). The control group consisted of women who did not become ill during the study period (n=71). Clinical manifestations of PCS were defined as symptoms that were absent before COVID-19, occurred no earlier than four weeks after disease onset, lasted at least two months, and could not be explained by alternative diagnoses. A statistical database was formed based on primary medical documentation and an active survey of patients, using a special questionnaire with symptom assessment on a 10-point scale. The survey was conducted in the 1st phase of the menstrual cycle to exclude the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, which have a clinical picture similar to that of PCS. Results: The incidence of new persistent symptoms during the pandemic in young initially somatically healthy women who had recovered from COVID-19 and in the non-diseased group was similar:96.1% and 93.0%, respectively (OR=1.88 (95% CI 0.58; 6.14); pχ2=0.327). Only patients who had NCI experienced symptoms such as coughing (43.6%), shortness of breath (26.5%), chest pain (18.2%), weight loss (18.8%), hair loss (60.8%) %) (in the comparison group 0.0%, pχ2<0.001). Patients with PCS more often reported memory impairment – 49.2% vs. 12.7% (OR=6.66 (95% CI 3.13; 14.21); pχ2<0.001); headache – 43.1% vs. 11.3% (OR=5.96 (95% CI 2.7; 13.17); pχ2<0.001); depression – 19.9% vs. 8.5% (OR=2.69 (95% CI 1.08; 6.7); pχ2=0.029); myalgia – 31.5% versus 8.5% (OR=4.98 (95% CI 2.04;12.17); pχ2<0.001). Fatigue/fatigue (69.0% vs. 71.8%, pχ2=0.66), drowsiness (54.9% vs. 43.6%, pχ2=0.11), palpitations (19.7% vs. 29.8%, pχ2=0.1), changes in menstrual cycle (22.5% vs. 21.0%, pχ2=0.865), skin manifestations (2.8% vs. 6.6%, pχ2=0.24), and insomnia developed significantly more frequently (32.4% vs. 26.0%, pχ2=0.012). After COVID-19, the intensity of memory impairment (4.0 versus 1.0 points, p<0.001) and headache (5.0 versus 3.0 points; p=0.001) were more pronounced. Myalgia (5.0 vs. 1.0 points, p<0.001), and insomnia (3.0 versus 5.0 points; p=0.004) were less severe. Conclusion: PCS is highly prevalent among initially somatically healthy women of early reproductive age. The occurrence of several similar symptoms of similar frequency in women who did not become ill during the pandemic may be associated with post-traumatic stress-anxiety disorder. Further in-depth interdisciplinary studies are required to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the development of new, persistent symptoms associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Authors' contributions: Belokrinitskaya T.E., Frolova N.I. – conception and design of the study, manuscript drafting; Zhamyanova Ch.C., Kargina K.A., Osmonova Sh.R., Shametova E.A. – primary material collection, formation of databases; Mudrov V.A. – statistical analysis; Belokrinitskaya T.E. – manuscript editing. Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Funding: There was no funding for this study. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the residents of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics, and the Department of Postgraduate Education, Chita State Medical Academy Agarkova M.A., Bagyshova A.N., Gladysheva N.A., Mikayelyan E.A., Pivneva A.A., Rodionova K.A., Tyukavkin A.V. for their help in conducting the patients’ survey. Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia. Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data. Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator. For citation: Belokrinitskaya T.E., Frolova N.I., Mudrov V.A., Kargina K.A., Shametova E.A., Zhamyanova Ch.Tch., Osmonova Sh.R. Post-COVID-19 syndrome in early reproductive age women. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (7): 47-54 (in Russian) https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.67Belokrinitskaya T.E., Frolova N.I., Mudrov V.A., Kargina K.A., Shametova E.A., Zhamyanova Ch.Tch., Osmonova Sh.R.

Keywords

Three years have passed since the World Health Organization (WHO) officially named the infection caused by the new coronavirus COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) on February 11, 2020. On March 11, 2020, the WHO announced the beginning of a pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2. According to WHO statistics, over the course of the three-year pandemic, there have been more than 758 million registered cases of COVID-19 and over 6.8 million deaths from the disease [1].

Another urgent medical and social problem associated with the pandemic is the emergence of new persistent symptoms after patients recover from the new coronavirus infection (NCI). Researchers worldwide have reported numerous cases showing that COVID-19 has various long-term effects on the respiratory, cardiovascular, nervous, endocrine, digestive systems, skin, and mental health [2–6].

International experts have proposed the term "post-COVID-19 syndrome" (PCS, post-COVID-19 syndrome, or long COVID) to describe persistent symptoms that arise or persist for more than 4 weeks from the initial clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [3, 7]. However, there is currently no globally recognized nomenclature for symptoms that persist after recovery from COVID-19, and there are no unified approaches to determining the duration of these symptoms [7–9].

In October 2021, WHO experts reached a consensus that PCS is a post-COVID-19 condition that occurs in individuals with probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. It typically manifests approximately 3 months after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, lasts for at least 2 months, and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. PCS symptoms usually affect a person's daily activities, may appear immediately after the acute phase of COVID-19 or persist after recovery, and may be permanent or recurrent. Currently, there are no specific criteria for the minimum number of symptoms required for diagnosis [10]. However, PCS is included in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, under the code U09.9, which refers to "Condition after COVID-19, unspecified."

Based on patient referrals and surveys of individuals who have recovered from COVID-19, it is estimated that 35% to 87.5% of people continue to experience various symptoms affecting multiple organs (such as headache, fatigue, sleep disturbances, memory issues, shortness of breath, cough, heart pain, palpitations/rhythm disturbances, myalgia, hair loss, skin rashes, etc.) [5–8, 11].

Recent research has revealed a complex multicomponent pathogenesis of PCS involving chronic immune inflammation, nervous system dysfunction, systemic endothelial damage, generalized microvascular thrombosis, and thrombovasculitis as the main pathogenetic mechanisms [2, 3, 5, 6, 12].

Despite the considerable number of publications on PCS, there are several contradictions. First, the severity of the initial NCI did not directly correlate with the incidence and severity of PCS symptoms. Even patients who experience asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 can subsequently experience PCS for an extended period [8, 13]. Second, PCS is believed to primarily develop in patients with comorbid conditions, such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. [3, 12, 14]. Thirdly, some authors attribute the symptoms of PCS to stress-anxiety disorders caused by the high morbidity and mortality rates, a constant sense of health-related threat, social isolation, negative changes in employment status and financial well-being, and other factors [13, 15, 16].

Despite a substantial number of publications on the pathogenesis and clinical presentation of PCS in adults and children, we found no information on this COVID-19 complication in young women. It is crucial to study this group, as they form the reproductive foundation of the nation, and the physical and mental well-being of future generations depends on their health [17].

This study aimed to compare the frequency and severity of new persistent symptoms in young, physically healthy women who have experienced NCI and those who have remained uninfected during the pandemic.

Materials and methods

To assess the independent impact of COVID-19 and avoid the effect of possible co-factors in the development of post-COVID syndrome (PCS), such as obesity, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and advanced age [3, 13], clinical groups were formed. These groups consisted of non-pregnant women under the age of 35 years who did not have excess body weight/obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic arterial hypertension, or other somatic or chronic infectious diseases. The study group included patients (n=181) who were diagnosed with COVID-19 between July and October 2021, with NCI confirmed by polymerase chain reaction in nasopharyngeal material [18]. The duration of illness was calculated from the first day of the onset of the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 to recovery, as confirmed by clinical, laboratory, and virological data. The severity of the acute period of NCI in patients was classified as mild, moderate, or severe (no critical cases were reported) following the criteria outlined in the clinical guidelines of the Russian Ministry of Health for COVID-19 [18]. Persistent symptoms of PCS were considered symptoms that were absent before COVID-19, appeared no earlier than 4 weeks from the onset of the disease, and lasted at least 2 months, without explanation by alternative diagnoses [3, 7, 10]. The control group consisted of women who had not contracted COVID-19 during the same period (n=71). The survey of the study participants was conducted in the 1st phase of the menstrual cycle to exclude symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, which may have a similar clinical presentation to PCS manifestations.

The severity of symptoms was assessed using the Yorkshire Rehabilitation Screen (COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Screen, C19-YRS), where each symptom was scored from 0 (absent) to 10 (very disturbing) [19].

A specialized questionnaire was developed to gather data from the database. This questionnaire contained information on the social, biomedical, and clinical characteristics of the women. Primary medical documentation (outpatient medical care records, form 025/y; medical history, form 003/y) was used to complete the questionnaire. An additional survey of the patients was conducted to assess persistent symptoms.

Statistical analysis

When conducting statistical analysis, the authors followed the principles of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and the recommendations of "Statistical Analysis and Methods in the Published Literature" (SAMPL) [20, 21]. The normality of the distribution of quantitative and ordinal variables, considering the number of studied groups to be more than 50 women, was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov criterion. The Mann–Whitney (U) test was used to compare two independent groups. Categorical data are described as counts and percentages, and comparisons were performed using Pearson's χ2 test. If the expected number of observations in at least one cell of the 2×2 table was less than 10, a chi-square test was used with Yates' correction for continuity. Fisher's exact test was employed if the expected number of observations in at least one cell of the 2×2 table was less than 5. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Given the retrospective nature of the analysis, the significance of the differences in categorical data was assessed by determining the odds ratio (OR). Statistical significance (p) was estimated based on the 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0 (International Business Machines Corporation, USA).

Results and discussion

The age of the patients was comparable, with a mean age of 25.0 (25.0; 26.6) years in the study group and 24.0 (24.0; 25.1) years in the control group. The difference in age between the two groups was not statistically significant (U=5606.0, p=0.12). This similarity in age, combined with the inclusion criteria for the study, allowed us to draw the following conclusions.

The incidence of new persistent symptoms during the pandemic was similar in young, initially somatically healthy women who had recovered from COVID-19 (96.1%, 174/181) and in the group without the disease (93.0%, 66/71). The odds ratio (OR) was 1.88 (95% CI 0.58; 6.14), and the p-value for the chi-square test was 0.327. We could not find any studies in the domestic or international literature that examined gender and age differences in the prevalence of post-COVID syndrome (PCS). Published data from different countries show a wide range of PCS prevalence, varying from 10.0% to 96.0%, with more than 50.0% in most cases [3, 11, 22]. In our study, we observed a relatively high incidence of persistent symptoms after recovery from NCI (96.1%), which is likely due to the young age of the patients (< 35 years) who were initially somatically healthy and thus more attentive to any previously absent clinical signs.

Regarding the severity of COVID-19, we found that 86.7% (157/181) of women in the early reproductive age group had mild disease, while 12.2% (22/181) had moderate disease. The odds ratio for moderate disease was 47.28 (95% CI 25.46; 87.81), and the chi-square test result was χ2=195.5, p<0.001. Only 1.1% (2/181) of patients had a severe disease (all pχ2<0.001). Overall, the incidence of moderate and severe COVID-19 was approximately 6.5 times lower than that of the mild form (OR=42.8, 95% CI 23.3; 78.6; χ2=201.4; p<0.001).

Therefore, our findings confirm that young age, absence of pregnancy, and lack of comorbidities significantly reduce the risk of moderate and severe NCI [18, 23].

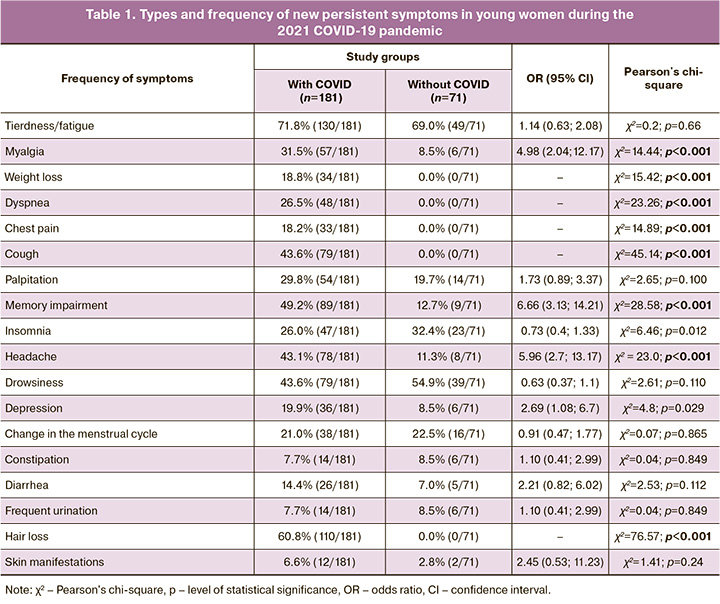

Table 1 presents the types and frequency of new persistent symptoms that occurred during the pandemic in women with and without COVID-19.

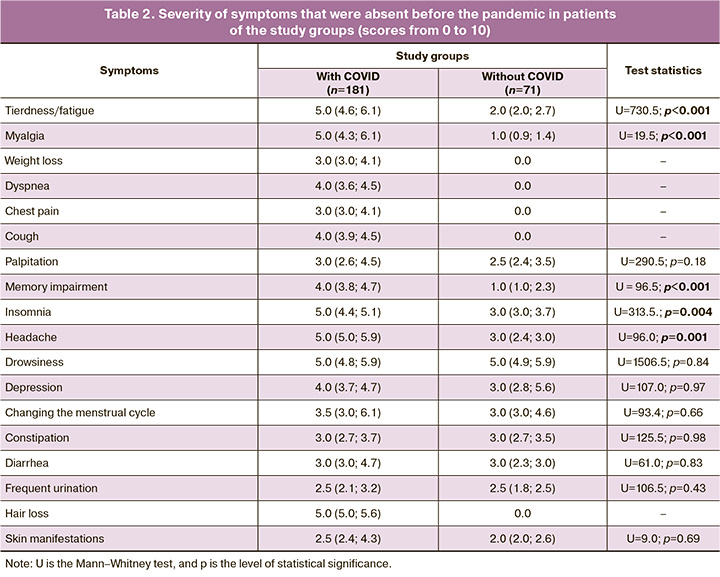

Tiredness and/or fatigue were the most common new persistent symptoms in young women during the pandemic, with the same frequency reported both after NCI and in those who were not ill: 71.8% (130/181) vs. 69.0 % (49/71, pχ2=0.66). Our findings regarding the prevalence of this symptom are generally consistent with the conclusions of other authors reporting that this complication develops at the highest frequency of 46.8–84.5% [3, 24]. However, it should be noted that the severity of the disease was higher in the group of women who had COVID-19 (5.0 points vs. 2.0 points, p<0.001).

Of the neurological symptoms of a patient with PCS, memory impairment was more often noted in 49.2% (89/181) versus 12.7% (9/71) (OR=6.66 (95% CI 3.13; 14.21); pχ2<0.001); headache – 43.1% (78/181) vs. 11.3% (8/71) (OR=5.96 (95% CI 2.7; 13.17); pχ2<0.001), the intensity of which exceeded that in the group of women who did not fall ill during the pandemic:4.0 vs. 1.0 points (p<0.001) and 5.0 vs. 3.0 points (p=0.001). A similar incidence of memory impairment (50%) in PCS was reported by Shan et al. (2022) in a large cohort of patients. They attributed this to pronounced bilateral metabolic disorders in the parts of the central nervous system that regulate cognitive processes and short-term and long-term memorization of information [25].

Women with a history of COVID-19 were significantly more likely to complain of depression than those who did not experienced the disease: 19.9% (36/181) vs. 8.5% (6/71) (OR=2.69 (95% CI 1.08; 6.7); pχ2=0.029). At the same time, the severity of symptoms was comparable:4.0 the 3.0 points (p=0.97). Domestic studies conducted on a population of women (78.9%) and men (21.1%) aged 18 and ≥ 55 years revealed a higher incidence of depression (68.6%) in the post-COVID period [3].

According to literature, pain in the muscles and joints is a fairly common symptom of PCS, with a frequency of 63.9% in the Russian population [3]. In our study, myalgia was registered in the post-COVID period in 31.5% (57/181) of cases and many times less often in those who did not have COVID-19 – 8.5% (6/71) (OR=4.98 (95% CI 2.04; 12.17); pχ2<0.001). The intensity of the symptom was more pronounced in those who had recovered from NCI:5.0 vs. 1.0 points (p<0.001).

Based on the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of COVID-19, our findings regarding the presence of cough in recovered patients in the post-COVID period look logical and explainable (43.6% (79/181) vs. 0.0% (0/71), pχ2<0.001), shortness of breath (26.5% (48/181) vs. 0.0% (0/71), pχ2<0.001), chest pain 18.2% (33/181) vs. 0.0% (0/71 ), pχ2< 0.001), weight loss (18.8% (34/181) vs. 0.0% (0/71), pχ2< 0.001), and hair loss (60.8% (110/181) vs 0, 0% (0/71), pχ2<0.001). In the current NICE (2020), CDC (2020), and WHO (2021) guidelines and available domestic and international sources, these symptoms are noted as characteristic of patients with PCS [3, 7–10, 19]. Experts believe that multiple organ disorders associated with PCS are caused by virus-induced inflammation. After the patient has recovered from COVID-19, the inflammation becomes immunological and chronic and is accompanied by hyperproduction of cytokines, damage to the vascular endothelium, hemocoagulation, autoimmune disorders, and oxidative stress [3, 4, 6, 12, 14, 25].

According to the information presented in Table 1, patients who did not have COVID-19 during the study period also reported numerous new persistent symptoms that had not been previously reported. Tiredness/fatigue (69.0% (49/71) versus 71.8% (130/181), pχ2=0.66), drowsiness (54.9% (39/71)), sleepiness (54.9% (39/71) 71) vs. 43.6% (79/181), pχ2=0.11), heartbeat (19.7% (14/71) vs. 29.8% (54/181), pχ2=0.1), change the menstrual cycle (22.5% (16/71) vs. 21.0% (38/181), pχ2=0.865), skin manifestations (2.8% (2/71) vs. 6.6% (12/181), pχ2=0.24). Insomnia occurred significantly more often (32.4% (23/71) vs. 26.0% (47/181), pχ2=0.012), although it was less severe (3, 0 vs 5.0, p=0.004).

Our findings regarding the occurrence of new persistent symptoms in patients who did not fall ill during the pandemic are explained in the studies by Shepeleva et al. (2020) [26], Abritalina E.Yu. (2021) [13] and Kotova et al. (2020) [15], who showed that COVID-19 has not only a direct (neurotoxic) but also an indirect effect on the human nervous system and psyche, due to the fear of infection and loss of loved ones in conditions of mass morbidity, difficult access to medical care, and lack of effective treatments. The psychological state of the population was significantly affected by negative emotional reactions to self-isolation, social distancing, panic demand for a number of goods, the difficulty of planning one's life in the future, changes in labor status and material well-being, and systematic information about the human victims of the pandemic.

Our study was conducted in the second year of the pandemic, in 2021, when the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant dominated, resulting from a natural mutation and characterized by greater pathogenicity, an increase in the incidence of severe pneumonia and adverse outcomes [27, 28]. Psychiatrists and psychologists noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, a specific syndrome was observed, called “headline stress disorder”: a high emotional response in the form of stress and anxiety. According to researchers, this syndrome can lead to physical symptoms, including palpitations, insomnia, menstrual irregularities, and other psychosomatic disorders. The symptoms and early warning signs of post-traumatic stress disorder may be chronic or episodic in nature [13, 15].

Thus, the formation of PCS is undoubtedly influenced by the biological properties of SARS-CoV-2 and its ability to cause a number of multiple organ pathological processes caused by chronic immune inflammation, generalized endotheliopathy, microthrombosis, and vasculitis. [2, 3, 5, 6, 12]. The emergence of new persistent symptoms similar to the clinical manifestations of PCS in young somatically healthy women who have not contracted COVID-19 may be caused by a high emotional response to changes in living conditions during the pandemic, followed by post-traumatic stress-anxiety disorders in the form of a whole spectrum of psychosomatic disorders [13, 15, 26].

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that PCS is highly prevalent among initially somatically healthy women of an early reproductive age. The occurrence of several similar symptoms of similar frequency in women who did not become ill during the pandemic may be associated with post-traumatic stress-anxiety disorder. Further in-depth interdisciplinary studies are required to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the development of new persistent symptoms associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- https://covid19.who.int/

- Адамян Л.В., Вечорко В.И., Конышева О.В., Харченко Э.И., Дорошенко Д.А. Постковидный синдром в акушерстве и репродуктивной медицине. Проблемы репродукции. 2021; 27(6): 30-40. [Adamyan L.V., Vechorko V.I., Konysheva O.V., Kharchenko E.I., Doroshenko D.A. Post-COVID-19 syndrome in Obstetrics and Reproductive Medicine. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2021; 27(6): 30 40. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro20212706130.

- Воробьев П.А., ред. Рекомендации по ведению больных с коронавирусной инфекцией COVID-19 в острой фазе и при постковидном синдроме в амбулаторных условиях. Проблемы стандартизации в здравоохранении. 2021; 7-8: 3-96. [Vorobyev P.A., ed. Recommendations for the management of patients with COVID-19 coronavirus infection in the acute phase and with post-COVID syndrome on an outpatient basis. Problems of Standardization in Healthcare. 2021; (7-8): 3-96. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.26347/1607-2502202107-08003-096.

- Baig A.M. Chronic COVID syndrome: need for an appropriate medical terminology for long-COVID and COVID long‐haulers. J. Med. Virol. 2021; 93(5): 2555-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26624.

- Silva Andrade B., Siqueira S., de Assis Soares W.R., de Souza Rangel F., Santos N.O., Dos Santos Freitas A. et al. Long-COVID and Post-COVID health complications: an Up-to-date review on clinical conditions and their possible molecular mechanisms. Viruses. 2021; 13(4): 700. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/v13040700.

- Maamar M., Artime A., Pariente E., Fierro P., Ruiz Y., Gutiérrez S. et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome, low-grade inflammation and inflammatory markers: a cross-sectional study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2022; 38(6): 901-9.https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2022.2042991.

- COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 NICE guideline [NG188]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 Accesseed 18.12.2020.

- Greenhalgh T., Knight M., A'Court C., Buxton M., Husain L. Management of post-acute COVID-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020; 370: m3026. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3026.

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C., Palacios-Ceña D., Gómez-Mayordomo V., Cuadrado M.L., Florencio L.L. Defining post-COVID symptoms (postacute COVID, long COVID, persistent post-COVID): an integrative classification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021; 18(5): 2621. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052621.

- Soriano J.B., Murthy S., Marshall J.C., Relan P., Diaz J.V.; WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022; 22(4): e102-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1

- Pavli A., Theodoridou M., Maltezou H.C. Post-COVID syndrome: incidence, clinical spectrum, and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Arch. Med. Res. 2021; 52(6): 575-81. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.010.

- Maltezou H.C., Pavli A., Tsakris A. Post-COVID syndrome: an insight on its pathogenesis. Vaccines (Basel). 2021; 9(5): 497. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9050497.

- Абриталин Е.Ю. О причинах возникновения и лечении депрессивных нарушений при COVID-19. Журнал неврологии и психиатрии им. С.С. Корсакова. 2021;121(8): 87-92. [Abritalin E.Yu. About the causes and therapy of depressive disorders in COVID-19. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry named after S.S. Korsakov. 2021; 121(8): 87-92. (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/jnevro202112108187.

- Ludvigsson J.F. Case report and systematic review suggest that children may experience similar long-term effects to adults after clinical COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. 2021; 110: 914-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apa.15673.

- Котова О.В., Медведев В.Э., Акарачкова Е.С., Беляев А.А. Ковид-19 и стресс-связанные расстройства. Журнал неврологии и психиатрии им. С.С. Корсакова. 2021; 121(5-2): 122-8. [Kotova O.V., Medvedev V.E., Akarachkova E.S., Belyaev A.A. COVID-19 and stress-related disorders. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry imeni S.S. Korsakov. 2021; 121(5-2): 122-8. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/jnevro2021121052122.

- Taylor S., Landry C.A., Paluszek M.M., Fergus T.A., McKay D., Asmundson G.J.G. COVID stress syndrome: concept, structure, and correlates. Depress Anxiety. 2020; 37(8): 706-14. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.23071.

- Нацун Л.Н. Здоровье женщин репродуктивного возраста. Society and Security Insights. 2020; 3: 167-81. [Natsun L.N. Women’s of reproductive age health. Society and Security Insights. 2020; (3): 167-81. (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.14258/ssi(2020)3-12.

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Временные методические рекомендации профилактика, диагностика и лечение новой коронавирусной инфекции (COVID-19). Версия 17 (14.12.2022). 260с. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Temporary methodological recommendations prevention, diagnosis and treatment of new coronavirus infection (COVID-19). Version 17 (28.01.2023). 260p. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/061/254/original/%D0%92%D0%9C%D0%A0_COVID-19_V17.pdf?1671088207

- Sivan M., Taylor S. NICE guideline on long COVID. BMJ. 2020; 371: m4938. https://dx,doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4938.

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication, 2011. Available at: https://www.icjme.org Accessed 25.02.2023.

- Lang T.A., Altman D.G. Statistical analyses and methods in the published literature: The SAMPL guidelines. Medical Writing. 2016; 25(3): 31-6.https://dx.doi.org/10.18243/eon/2016.9.7.4.

- Kayaaslan B., Eser F., Kalem A.K., Kaya G., Kaplan B., Kacar D. et al. Post-COVID syndrome: a single-center questionnaire study on 1007 participants recovered from COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021; 93(12): 6566-74.https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27198.

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Организация оказания медицинской помощи беременным, роженицам, родильницам и новорожденным при новой коронавирусной инфекции COVID-19. Методические рекомендации. Версия 5. 28.12.2021. 135c. [Ministry of Health of еру Russian Federation. Organization of medical care for pregnant women, women in labor, women in labor and newborns with a new coronavirus infection COVID-19. Methodological guidelines. Version 5. 28.12.2021. 135 р. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/059/052/original/BMP_preg_5.pdf

- Sandler C.X., Wyller V.B.B., Moss-Morris R., Buchwald D., Crawley E., Hautvast J. et al. Long COVID and post-infective fatigue syndrome: a review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021; 8(10): ofab440. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofab440.

- Shan D., Li S., Xu R., Nie G., Xie Y., Han J. et al. Post-COVID-19 human memory impairment: A PRISMA-based systematic review of evidence from brain imaging studies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022; 14: 1077384.https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.1077384.

- Шепелева И.И., Чернышева А.А., Кирьянова Е.М., Сальникова Л.И., Гурина О.И. COVID-19: поражение нервной системы и психологопсихиатрические осложнения. Социальная и клиническая психиатрия. 2020; 30(4): 76-82. [Shepeleva I.I., Chernysheva A.A., Kiryanova E.M., Salnikova L.I., Gurina O.I. The nervous system damages and psychological and psychiatric complications on the COVID-19 pandemic. Social and Clinical Psychiatry. 2020; 30(4): 76-82. (in Russian)].

- Sharif N., Alzahrani K.J., Ahmed S.N., Khan A., Banjer H.J., Alzahrani F.M. et al. Genomic surveillance, evolution and global transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during 2019–2022. PLoS One. 2022; 17(8): e0271074.https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271074.

- Белокриницкая Т.Е., Фролова Н.И., Колмакова К.А., Шаметова Е.А. Факторы риска и особенности течения COVID-19 у беременных: сравнительный анализ эпидемических вспышек 2020 и 2021 г. Гинекология. 2021; 23(5): 421-7. [Belokrinitskaya T.E., Frolova N.I., Kolmakova K.A., Shametova E.A. Risk factors and features of COVID-19 course in pregnant women: a comparative analysis of epidemic outbreaks in 2020 and 2021. Gynecology. 2021; 23(5): 421-7 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.26442/20795696.2021.5.201107.

Received 15.05.2023

Accepted 16.06.2023

About the Authors

Tatiana E. Belokrinitskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of the Pediatric Faculty and Faculty of Professional Retraining, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(3022) 32-30-58, tanbell24@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5447-4223, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.Natalya I. Frolova, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Pediatric Faculty and Faculty of Professional Retraining,

Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, taasyaa@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7433-6012, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Viktor A. Mudrov, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Pediatric Faculty and Faculty of Professional Retraining,

Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, taasyaa@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7433-6012, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Kristina A. Kargina, Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Pediatric Faculty and Faculty of Professional Retraining, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, kristino4ka100@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8817-6072, 672000, Russian Federation, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Evgeniya A. Shametova, Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Pediatric Faculty and Faculty of Professional Retraining, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, solnce181190@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2205-2384, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39а.

Chimita Tch. Zhamyanova, PhD Student of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Pediatric Faculty and Faculty of Professional Retraining, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5293-615Х, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39а.

Shakhnozakhon R. Osmonova, PhD Student of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Pediatric Faculty and Faculty of Professional Retraining,

Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5505-3818, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39а.

Corresponding author: Tatiana E. Belokrinitskaya, tanbell24@mail.ru