Postcovid syndrome in pregnant women

Objective: To assess the prevalence and characteristics of postcovid syndrome (PCS) in pregnant women who have not concomitant comorbid pathology. Materials and methods: To assess the independent impact of the novel coronavirus infection on the development of PCS, the investigation involved women who had no known risk factors: those who are younger than 35 years, are without overweight/obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, and other somatic and chronic infectious diseases, who experienced COVID-19 in July to October 2021. A study group consisted of patients without uncomplicated pregnancy (n=111); a comparison group included non-pregnant women (n=181). SARS-CoV-2 was identified by a polymerase chain reaction assay in the nasopharyngeal material in all cases. The symptoms of PCS were considered to be the clinical manifestations that were absent before COVID-19 and appeared not earlier than 4 weeks from the onset of the disease and lasted at least 2 months, which could not be explained by alternative diagnoses. The statistical database had been formed on the basis of primary medical documentation and an interview of the patients according to a special questionaire with an assessment of the existing symptoms on a 10-score scale. Results: The pregnant women were 2.0 and 6.6 times more likely to have been ill with moderate and severe COVID infection, respectively, as compared with non-pregnant women (χ2=16.42; p<0.001; OR=2.99 (95% CI, 1.68; 5.35); p<0.001), which caused the increased risk of their hospitalization (OR=3.59 (95% CI, 2.06; 6.25); p<0.001). The incidence of PCS had no differences and amounted to 93.7 and 97.2%, respectively (p>0.05). PCS in the pregnant women was more frequently manifested by the development of dyspnea (37.8% vs 26.5%) (χ2=4.13; p=0.043; OR=1.69 (95% CI, 1.02; 2.80); p<0.05); moreover, the severity of the symptom did not differ in the comparison groups. Coughing and frequent urination occurred with same frequency in the pregnant and non-pregnant women, but their intensity prevailed in the maternal group. The pregnant women were less likely to have hair loss (46.8% vs 60.8% (χ2=5.4; p=0.021) with the symptom severity in the groups. Headache occurred less frequently in the pregnant women (30.6% vs 43.1% (χ2=4.52; p=0.034) and was less intensive (3.0 (2.6; 5.2) vs 5.0 (5.0; 5.9) scores (p=0.047). Other PCS symptoms (fatigue/easy fatigability, myalgia, weight loss, chest pain, palpitation, memory impairment, sleep disorders, depression, etc.) were recorded with the same frequency and severity. Conclusion: Our investigation has demonstrated the widespread prevalence of PCS in young initially somatically healthy pregnant and non-pregnant women. The obtained facts regarding the symptoms identified in the pregnant women can be partly explained by physiological gestational changes in the mother’s body. However, further large-scale and longer-term investigations are needed to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms of the development of PCS and its possible consequences in pregnant women. Authors' contributions: Belokrinitskaya T.E, Frolova N.I. – the concept and design of the investigation, writing the text; Agarkova M.A., Zhamiyanova Ch.Ts., Kargina K.A., Shametova E.A. – primary material collection, formation of databases; Mudrov V.А. – statistical data processing; Belokrinitskaya T.E. – editing. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. Funding: The investigation has not been sponsored. Acknowledgement: The authors express their gratitude to the clinical residents Sh.R. Osmonova, E.A. Mikaelyan, A.V. Tyukavkina, D.Ts. Dogonova, A.A. Oslopova, A.A. Pivneva, and A.V. Rzhevtseva of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education, Chita State Medical Academy for assistance in conducting a questionnaire survey of the patients. Ethical Approval: The investigation has been approved by the Local Ethics Committee, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia. Patient Consent for Publication: All patients have signed an informed consent form to publication to their data. Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator. For citation: Belokrinitskaya T.Е., Frolova N.I., Mudrov V.A., Kargina K.A., Shametova E.A., Agarkova M.A., Zhamiyanova Ch.Ts. Postcovid syndrome in pregnant women. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (6): 60-68 (in Russian) https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.54Belokrinitskaya T.Е., Frolova N.I., Mudrov V.A., Kargina K.A., Shametova E.A., Agarkova M.A., Zhamiyanova Ch.Ts.

Keywords

The pandemic of the novel coronavirus infection (NCI) COVID-19 that originated in December 2019 in the town of Wuhan, Hubei Province (China) and rapidly swept the whole world, became one of the largest epidemics and the hardest trials for humanity and the world’s health systems. At the very beginning of the pandemic, the severe course of the disease induced by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) caused serious concern due to the lack of effective methods for disease treatment and prevention. However, as some time elapsed, there was another problem that is the appearance of a set of a wide variety of debilitating symptoms after recovery of the patients. Numerous publications in different countries have shown that the experienced COVID-19 has long-term pathological effects on almost all body systems: respiratory, cardiovascular, nervous, and mental ones, the skin, gastrointestinal tract, etc. [1–4]. According to the conducted investigations and active patient surveys, among the cured individuals, a high proportion (35 to 87.5%) after the acute period of infection continue to suffer from different symptoms, including dyspnea, coughing, myalgia, fatigue, and headache [5–8].

As of now, there have been published data on that the people who have experienced asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 also subsequently for a long time suffer from postcovid syndrome (PCS) [8]. This fact can lead to the conclusion that NCI causes significantly more damage to human health than is manifested in the infected people in the acute period of the disease.

At the present stage of studying the problem, in the world there is no unified nomenclature of the symptoms that persist after recovery from COVID-19; the duration of the periods of their manifestation differs in the definitions given by leading international organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention, USA), and the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), United Kingdom) [1, 9, 10].

Greenhalgh et al. (2020) identified the symptoms of PCS beyond 3 weeks from the onset of the disease as a subacute period of COVID-19, whereas more than 12 weeks as chronic COVID-19 [9]. The CDC experts proposed to divide the disease into 3 periods from the onset of symptoms: an acute (the first 2 weeks) period, a subacute one (from 2 to 4 weeks); and a late complication period (more than 4 weeks – Post-COVID-19 syndrome, Long Covid) [10].

According to the WHO expert consensus dated October 6, 2021, on the treatment of patients with COVID-19, PCS is a condition after COVID-19, which occurs in individuals with probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection usually at 3 months after the appearance of COVID-19 symptoms that last at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. The common symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea, cognitive dysfunction, but also other symptoms that usually affect day-to-day activity. The symptoms may manifest for the first time after primary recovery after an acute COVID-19 episode or persist after the initial illness, or recur over time; moreover, there is no minimum number of symptoms needed to make a diagnosis [11]. PCS is included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) under Code U09.9 formulating as “A post-COVID condition, unspecified”.

Despite a fairly large number of publications devoted to the prevalence, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and treatment of PCS; in the Russian and international databases, there were only single mentions on this complication of COVID-19 in pregnant women were [12].

Objective: to assess the prevalence and characteristics of postcovid syndrome (PCS) in pregnant women who do not have concomitant comorbid pathology.

Materials and methods

There is an opinion that PCS in aged patients is caused by risk factors, such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus [13]. To assess the independent impact of NCI on the development of PCS, the investigation involved women who had not the known risk factors: those who were younger than 35 years, had no overweight/obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, or other somatic and chronic infectious disease, and experienced COVID-19 in July to October 2021. In all cases, the virus SARS-CoV-2 was identified in the nasopharyngeal material by a polymerase chain reaction assay [14, 15].

The severity of acute COVID-19 disease in the patients was ranked as mild, moderate, or severe (there were no critical course cases) in accordance of the clinical practice guidelines of the Ministry of Health of Russia on COVID-19 [14, 15]. The disease duration was calculated from the first day of the appearance of clinical symptoms of COVID-19 to clinical and virologically confirmed recovery. The symptoms of PCS were deemed to be the clinical manifestations that occur no earlier than 4 weeks from the onset of the disease and lasted at least 2 months and that cannot be explained by alternative diagnoses [3, 5, 10].

All the investigation participants assessed the symptoms that were absent before COVID-19 and appeared after recovery [3, 5]. To rule out the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, which have the similar clinical presentations with the manifestations of postcovid disorders, the non-pregnant women assessed whether the persistent symptoms were present in Phase 1 of the menstrual cycle. To evaluate the severity of symptoms, the authors used the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Screen (C19-YRs), according to which, the investigation participants estimated each symptom in scores from 0 (no problems) to 10 (it disturbs extremely) [5].

To form a database, a special questionnaire containing information on the social, biomedical, and clinical characteristics of the examinees was designed, which to be fill in, the authors used primary medical documentation (an individual prenatal record of a patient receiving outpatient medical care (Form 111/y), a medical record of a patient receiving outpatient medical care (Form 025/y), a case report history (Form 003/y), a delivery record (Form N (096/y-20); an additional patient survey was made to assess the symptoms of PCS.

Statistical analysis

When carrying out a statistical analysis, the authors are guided by the principles of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and by the recommendations of the “Statistical Analysis and Methods in Published Literature (SAMPLE)” [16, 17]. Analysis of the normality of the distribution of quantitative and ordinal signs, by taking into account the number of investigation groups equal to more than 50 women, was carried out, by assessing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two independent groups by one quantitative sign. Nominal data were described with absolute values and percentages; a comparison was made using the Pearson’s χ2 test. Yates’s chi-squared test for continuity was employed if there was less than 10 expected observations is at least in one of the cells of a four-field table.

Fisher’s exact test was used in the situation where there were less than 5 expected observations in at least in one of the cells of a four-field table. In all cases, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Taking into account the retrospective analysis of the effective and factor signs, the significance of differences in the nominal data was assessed by determining the odds ratio (OR). The statistical significance (p) was estimated based on the values of 95% confidence interval (CI). The results of the investigation were statistically processed using the IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0 (International Business Machines Corporation, USA).

Results and discussion

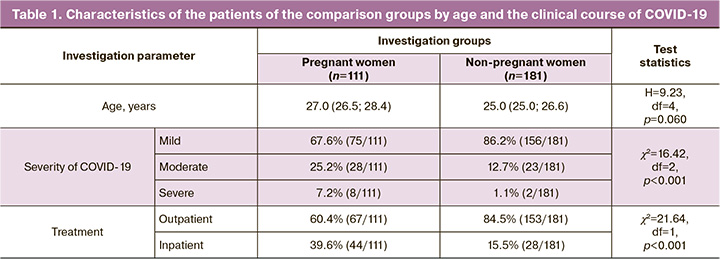

Table 1 gives the characteristics of the female patients of the comparison groups by age and the clinical course of COVID-19. The patients’ age in the examined clinical groups had no statistically significant differences and was 27.0 (26.5; 28.4) years in the pregnant women and 25.0 (25.0; 26.6) years in the non-pregnant women (p=0.06) (Table 1).

Assessing the severity of the COVID-19 course established that the initially healthy pregnant women were 2.0 and 6.6 times more likely be ill with moderate and severe COVID-19 infection, respectively, as compared with non-pregnant women comparable in somatic history (χ2=16.42; p<0.001). By and large, the risk of moderate and severe COVID-19 is almost thrice higher than that in the non-pregnant patients (OR=2.99 [95% CI, 1.68; 5.35]; p<0.001), which makes it possible to consider pregnant women to be included in a high-risk group. This fact is confirmed by a large number of pregnant patients requiring inpatient treatment: 39.6% versus 15.5% (χ2=21.64; p<0.001). The risk of hospitalization of a pregnant woman exceeds that of a non-pregnant woman by almost 3.6 times (OR=3.59 [95% CI, 2.06; 6.25]; p<0,001).

In the first year of the pandemic, numerous concluded that pregnant women with COVID-19 were not at higher risk for developing severe symptoms and in most cases they were characterized by the asymptomatic and mild course of the disease [18–21]. However, the subsequent investigations conducted in different countries revealed a risk for more severe NCI in the pregnant women as compared with the general population [22–25]. The authors explain this fact, firstly, by the process of natural mutation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and by the emergence of a more virulent and pathogenic Delta strain that dominated in the world in the second year of the pandemic [26, 27]; secondly, by the gestational physiological changes in the respiratory, cardiovascular, immune, hemocoagulation, and other the most important systems of the mother’s body, which create the premorbid background for a higher susceptibility to respiratory viral agents, more severe pathological disorders and, accordingly, the more severe course of the infectious process [14, 23, 24, 28].

The incidence of PCS had no statistically significant differences in the declared patient groups and was 93.7% (104/111) in the pregnant women and 97.2% (176/181) in the non-pregnant ones (F=0.25; p>0.05). We have not found in the available literature any information on the prevalence of this complication of COVID-19 in pregnant women. Russian and foreign authors give very variable population values: from 13.3 to 96.0%, but in most cases, that is more than 50.0% [3, 8].

The fairly high prevalence of persistent symptoms after recovery from NCI in the patients involved in our investigation was explained by the fact that the women were young, initially somatically healthy, and therefore attention was fixed on any clinical sign that was earlier absent in them.

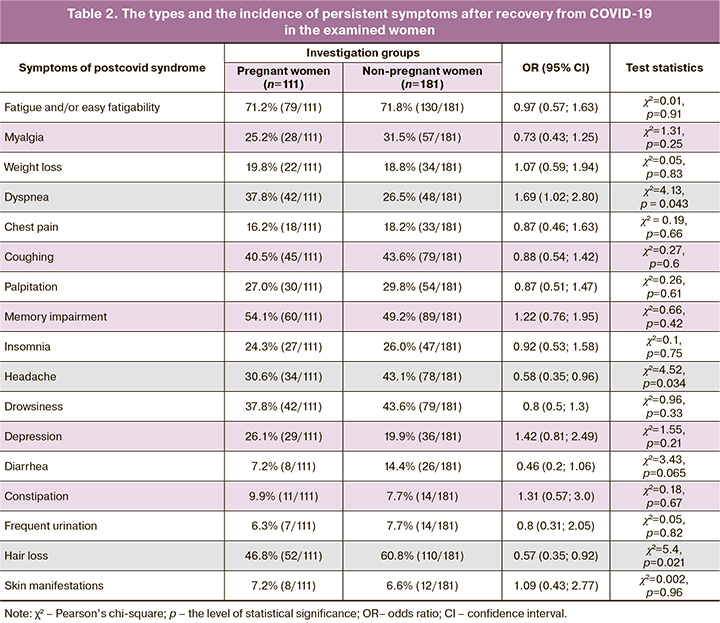

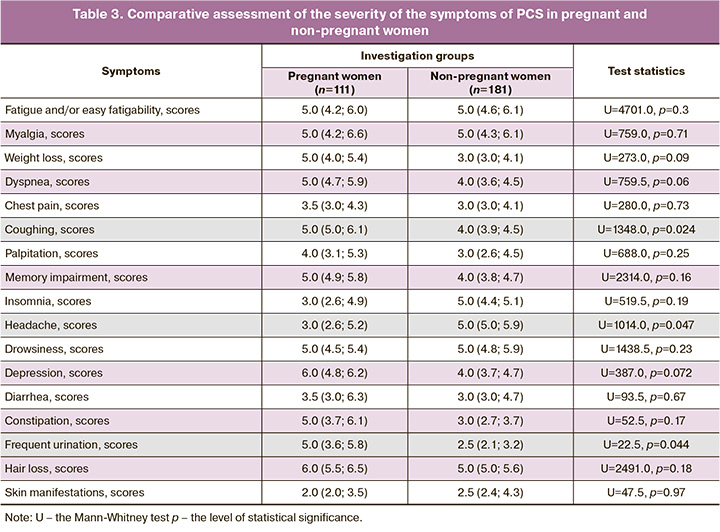

The types and the incidence of persistent symptoms after recovery from COVID-19 in pregnant and non-pregnant women are given in Table 2; the estimation of their severity in scores is shown in Table 3.

In our study, fatigue and/or easy fatigability proved to be the most common symptoms of PCS (71.2% (79/111) in the group of pregnant women, 71.8% (130/181) in the non-pregnant women, pχ2=0.91), which coincides with the conclusions of other Russian authors авторов, who identified the incidence of this complication, which was about 80% in a large-scale survey (n=1400) [3]. We found no differences in both the prevalence of this symptom and the degree of its severity (5.0 versus 5.0 scores; p=0.30) in the pregnant and non-pregnant women, which is probably due to their young age and the absence of a background somatic disease.

Memory impairment was the second common symptom that appeared in the postcovid period in the patients of our groups studied. The frequency and severity of this complication had no significant differences in pregnant and non-pregnant women (54.1% (60/111) and 49.2% (89/181); pχ2=0.42; 4.0 [3.8; 4.7] and 5.0 [4.9; 5.8] scores; p=0.16). We note that the similar frequency of memory impairment (50%) was revealed by a meta-analysis by Shan D. et al. (2022), who explained the development of the deficiency by pronounced bilateral metabolic disorders in the central nervous system areas responsible for cognitive processes, short-term and long-term information memorization [29].

The dermatological symptom, such as hair loss, ranked third, the frequency of which was generally 55.5% (162/292) and exceeded the other authors’ figures 16.5% [8]. 35.1% [3]. Ii is of interest that the rate of hair loss in the pregnant women was lower than that in the non-pregnant women: 46.8% (52/111) versus 60.8% (110/181), respectively (pχ2=0.021) with the similar symptom intensity of 6.0 [5.5; 6.5] versus 5.0 [5.0; 5.6] scores (p=0.18). This fact is due to the fact that under the influence of elevated estrogen and androgen levels that are typical for the gestation period, there is an elongation and an acceleration of hair growth rates, a change in the texture (more frequently thickening, coarsening) of hair, with a subsequent decrease in its loss [28, 30].

Coughing is the fourth most common symptom of PCS in the pregnant women, the proportion of which did not differ from that in the group of non-pregnant women: 40.5% (45/111) versus 43.6% (79/181), respectively (pχ2=0.60). We note that the severity of coughing prevailed in the group of mothers: 5.0 [5.0; 6.1] versus 4.0 [3.9; 4.5] (p=0.024). We explain the found differences, firstly, by the more severe course of COVID-19 (Table 1), secondly, the presence of gastroesophageal reflux in the pregnant women, which is caused by an increase in intraabdominal pressure, the rate of which in uncomplicated gestation amounts to as much as 50–75% [31, 32]. Furthermore, the investigation by Ryabova M.A. et al. (2016) revealed that gastroesophageal reflux was the coughing in 77% of the pregnant women without a history of bronchopulmonary disease [32].

PCS in the pregnant women as compared to the non-pregnant women was more often manifested by the development of dyspnea: 37.8% (42/111) versus 26.5% (48/181), respectively (pχ2=0.043). The probability of maintaining shortness of breath in the pregnant women in the period after recovery from NCI is 1.7 times higher than that in the non-pregnant patients (OR=1.69 (95% CI, 1.02; 2.80) (p<0.05), which makes it possible to consider pregnant women at risk.

It is known that in late pregnancy due to a significant increase in the size of the uterus, functional residual lung capacity and total lung volume decrease the respiratory excursion of the lung declines. This entails an increase in the frequency of respiratory movements by 10% and an appearance of dyspnea even during insignificant physical exercises [28]. On the other hand, Miwa M. et al. (2021) found that persistent significant lung dysfunction was observed in 47% of the patients who did not receive invasive artificial ventilation during COVID-19 disease [33] that is caused by virus-induced inflammation, cytokine hyperproduction, vascular endothelial lesion, hemocoagulational and immune disorders, and oxidative stress [3, 6]. By and large, different general population studies show that the incidence of dyspnea after experienced SARS-COV-2 infection varies very widely from 7.7 to 87.1%, which is due to the substantial heterogeneity of age, ethnic, and sociomedical groups of the examined patients [2, 3, 7, 8].

Drowsiness was recorded in the pregnant women with the same frequency, as well as dyspnea; however, the prevalence of sleep disorders in the compared groups had no differences: 37.8% (42/111) in the pregnant women and 43.6% (79/181) in the non-pregnant women (pχ2=0.33). We identified the similar patterns for insomnia (24.3% (27/111) versus 26.0% (47/181), pχ2=0.75) and depression (26.1% (29/111) versus 19.9% (36/181), pχ2=0.21); According to a Russian population study, these symptoms were noted by a much larger proportion of people of both sexes, different age groups who have experienced COVID-19, including those who had chronic somatic diseases: drowsiness (72%), insomnia (70–78%), depression (68.6%) [3].

We have obtained comparable results with the data by P.A. Vorobyev et al. (2021) on the prevalence of the symptom headache in the postcovid period: 43.1% (78/181) in our examined non-pregnant women versus 43.8% in the patients of the general population [3]. We note that the rate and severity of this symptom were significantly lower in the group of pregnant women 30.6% (34/111) compared to young non-pregnant women (pχ2=0,034); 3.0 (2.6; 5.2) versus 5.0 (5.0; 5.9) scores (p=0.047). This fact needs a further investigation in large groups, by additionally applying neurophysiological and radiation studies.

The remaining symptoms of PCS were found in the declared groups of patients with a significantly lower rate (Table 2). However, let us note that the pregnant women showed a greater intensity of frequent urination: 5.0 (3.6; 5.8), 2.5 (2.1; 3.2) scores (p=0.044), respectively (Table 3), which is attributable to the anatomic and physiological characteristics of the urinary system in the period of gestation: to the displacement of the bladder upward, to the increase in its receptor excitability and to the pressure of the growing uterus on the bladder [28].

Thus, pregnant women without an underlying somatic disease are a risk group in the moderate and severe course of COVID-19. PCS developed in 93.7% (104/111) of the pregnant women and was significantly more frequently manifested by dyspnea, the greater intensity of coughing and frequent urination; there was less often hair loss and headache that was also characterized by a lower intensity than that in the non-pregnant women.

Conclusion

Our investigation has demonstrated the wide prevalence of PCS in young initially somatically healthy pregnant and non-pregnant women. The obtained facts regarding the identified symptoms in the pregnant women can be partly explained by physiological gestational changes in the mother’s body. However, further large-scale and longer-term investigations are needed to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms of the development of PCS and its possible consequences in pregnant women.

References

- COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2020 Dec 18. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

- Адамян Л.В., Вечорко В.И., Конышева О.В., Харченко Э.И., Дорошенко Д.А. Постковидный синдром в акушерстве и репродуктивной медицине. Проблемы репродукции. 2021; 27(6): 30-40. [Adamyan L.V., Vechorko V.I., Konysheva O.V., Kharchenko E.I., Doroshenko D.A. Post-COVID-19 syndrome in obstetrics and reproductive medicine. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2021; 27(6): 30 40. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro20212706130.

- Воробьев П.А., ред. Рекомендации по ведению больных с коронавирусной инфекцией COVID-19 в острой фазе и при постковидном синдроме в амбулаторных условиях. Проблемы стандартизации в здравоохранении. 2021; 7-8: 3-96. [Vorobyev P.A., ed. Recommendations for the management of patients with COVID-19 coronavirus infection in the acute phase and with post-COSVID syndrome on an outpatient basis. Problems of Standardization in Healthcare. 2021; (7-8): 3-96. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.26347/1607-2502202107-08003-096.

- Baig A.M. Chronic COVID syndrome: need for an appropriate medical terminology for long-COVID and COVID long‐haulers. J. Med. Virol. 2021; 93(5): 2555-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26624.

- Sivan M., Taylor S. NICE guideline on long COVID. BMJ. 2020; 371: m4938. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4938.

- Pierce J.D., Shen Q., Cintron S.A., Hiebert J.B. Post-COVID-19 syndrome. Nurs. Res. 2022; 71(2): 164-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000565.

- Kamal M., Abo Omirah M., Hussein A., Saeed H. Assessment and characterisation of post-COVID-19 manifestations. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020; 75: e13746.https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13746.

- Kayaaslan B., Eser F., Kalem A.K., Kaya G., Kaplan B., Kacar D. et al. Post-COVID syndrome: a single-center questionnaire study on 1007 participants recovered from COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021; 93(12): 6566-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27198.

- Greenhalgh T., Knight M., A'Court C., Buxton M., Husain L. Management of post-acute COVID-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020; 370: m3026.https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3026.

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C., Palacios-Ceña D., Gómez-Mayordomo V., Cuadrado M.L., Florencio L.L. Defining post-COVID symptoms (postacute COVID, long COVID, persistent post-COVID): an integrative classification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021; 18(5): 2621. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052621.

- A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus 6 October 2021. 27р. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1

- Machado K., Ayuk P. Post-COVID-19 condition and pregnancy. Case Rep. Womens Health. 2023; 37: e00458. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crwh.2022.e00458.

- Ludvigsson J.F. Case report and systematic review suggest that children may experience similar long-term effects to adults after clinical COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. 2021; 110: 914-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apa.15673.

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Методические рекомендации «Организация оказания медицинской помощи беременным, роженицам, родильницам и новорожденным при новой коронавирусной инфекции COVID-19». Версия 5 (28.12.2021). 135с. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Methodological guidelines «Organization of medical care for pregnant women, women in labor, women in labor and newborns with a new coronavirus infection COVID-19». Version 5 (28.12.2021). 135р. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/059/052/original/BMP_preg_5.pdf

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Временные методические рекомендации «Профилактика, диагностика и лечение новой коронавирусной инфекции (COVID-19)». Версия 17 (14.12.2022). 260с. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Temporary methodological guidelines «Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of new coronavirus infection (COVID-19)». Version 17 (28.01.2023). 260p. (in Russian)]. Availadle at: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/061/254/original/%D0%92%D0%9C%D0%A0_COVID-19_V17.pdf

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication, 2011. Availadle at: https://www.icjme.org Accessed 25.02. 2023.

- Lang T.A., Altman D.G. Statistical analyses and methods in the published literature: The SAMPL guidelines. Medical Writing. 2016; 25(3): 31-6.https://dx.doi.org/10.18243/eon/2016.9.7.4.

- Zambrano L.D., Ellington S., Strid P., Galang R.R., Oduyebo T., Tong V.T. et al.; CDC COVID-19 Response Pregnancy and Infant Linked Outcomes Team. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status – united states, January 22-October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(44): 1641-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3.

- Белокриницкая Т.Е., Артымук Н.В., Филиппов О.С., Фролова Н.И. Клиническое течение, материнские и перинатальные исходы новой коронавирусной инфекции COVID-19 у беременных Сибири и Дальнего Востока. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 2: 48-54. [Belokrinitskaya T.E., Artymuk N.V., Filippov O.S., Frolova N.I. Clinical course, maternal and perinatal outcomes of a new coronavirus infection COVID-19 in pregnant women in Siberia and the Far East. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; (2): 48-54. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.2.48-54.

- Gulic T., Blagojevic Zagorac G. COVID-19 and pregnancy: are they friends or enemies? Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2021; 42(1): 57-62.https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/hmbci-2020-0054.

- Jafari M., Pormohammad A., Sheikh Neshin S.A., Ghorbani S., Bose D., Alimohammadi S. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 and comparison with control patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021; 31(5): 1-16. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2208.

- Белокриницкая Т.Е., Фролова Н.И., Колмакова К.А., Шаметова Е.А. Факторы риска и особенности течения COVID-19 у беременных: сравнительный анализ эпидемических вспышек 2020 и 2021г. Гинекология. 2021; 23(5): 421-7. [Belokrinitskaya T.E., Frolova N.I., Kolmakova K.A., Shametova E.A. Risk factors and features of COVID-19 course in pregnant women: a comparative analysis of epidemic outbreaks in 2020 and 2021. Gynecology. 2021; 23(5): 421-7. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.26442/20795696.2021.5.201107.

- Wang H., Li N., Sun C., Guo X., Su W., Song Q. et al. The association between pregnancy and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2022; 56: 188-95. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.03.060.

- Mihajlovic S., Nikolic D., Santric-Milicevic M., Milicic B., Rovcanin M., Acimovic A., Lackovic M. Four waves of the COVID-19 pandemic: comparison of clinical and pregnancy outcomes. Viruses. 2022; 14(12): 2648.https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/v14122648.

- Vousden N., Ramakrishnan R., Bunch K., Morris E., Simpson N., Gale C. et al. Management and implications of severe COVID-19 in pregnancy in the UK: Data from the UK Obstetric Surveillance System national cohort. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2022; 101(4): 461-70. https://dx.doi.org/doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14329.

- Andeweg S.P., Vennema H., Veldhuijzen I., Smorenburg N., Schmitz D., Zwagemaker F.; SeqNeth Molecular surveillance group; RIVM COVID-19 Molecular epidemiology group. Elevated risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 Beta, Gamma, and Delta variant compared to Alpha variant in vaccinated individuals. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022; 15(684): eabn4338.https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abn4338.

- Sharif N., Alzahrani K.J., Ahmed S.N., Khan A., Banjer H.J., Alzahrani F.M. et al. Genomic surveillance, evolution and global transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during 2019–2022. PLoS One. 2022; 17(8): e0271074. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271074.

- Артымук Н.В., Белокриницкая Т.Е. Клинические нормы. Акушерство и гинекология. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2018. 352с. [Artymuk N.V., Belokrinitskaya T.E. Clinical norms. Obstetrics and gynecology. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2018. 352p. (in Russian)].

- Shan D., Li S., Xu R., Nie G., Xie Y., Han J. et al. 2022; 14: 1077384.https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.1077384.

- ACOG. Your pregnancy and childbirth: month to month from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG; Seventh edition. January 26, 2021. 762p. Available at: https://www.acog.org/womens-health/your-pregnancy-and-childbirth

- Malfertheiner M., Malfertheiner P., Costa S.D., Pfeifer M., Ernst W., Seelbach-Göbel B., Malfertheiner F.S. Extraesophageal symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease during pregnancy. Z. Gastroenterol. 2015; 53(9): 1080-3.https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1399453.

- Рябова М.А., Шумилова Н.А., Лаврова О.В., Пестакова Л.В., Федотова Ю.С. Дифференциальная диагностика причин кашля у беременных. Вестник оториноларингологии. 2016; 81(4): 50-3.[Riabova M.A., Shumilova N.A., Lavrova O.V., Pestakova L.V., Fedotova Yu.S. Differential diagnostics of the causes responsible for a cough in the pregnant women. Bulletin of Otorhinolaryngology. 2016; 81(4): 50-3. (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/otorino201681450-53.

- Miwa M., Nakajima M., Kaszynski R.H., Hamada S., Ando H., Nakano T. et al. Abnormal pulmonary function and imaging studies in critical COVID-19 survivors at 100 days after the onset of symptoms. Respir. Investig. 2021; 59(5): 614-21. https://dx.doi.org/1016/j.resinv.2021.05.005.

Received 01.03.2023

Accepted 13.06.2023

About the Authors

Tatiana E. Belokrinitskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(3022)32-30-58, tanbell24@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5447-4223,672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Natalya I. Frolova, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, taasyaa@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7433-6012, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Viktor A. Mudrov, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education,

Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, mudrov_viktor@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7433-6012, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Kristina A. Kargina, Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, kristino4ka100@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8817-6072, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Evgeniya A. Shametova, Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education, Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, solnce181190@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2205-2384, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Maria A. Agarkova, Clinical Resident at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education,

Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, rinary_19@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-4924-1475, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Chimita Ts. Zhamiyanova, Clinical Resident at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Pediatrics and Faculty of Additional Professional Education,

Chita State Medical Academy, Ministry of Health of Russia, chimita_tunka@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-5293-615Х, 672000, Russia, Chita, Gorky str., 39a.

Corresponding author: Tatiana E. Belokrinitskaya, tanbell24@mail.ru