Experience of using a double balloon catheter for cervical ripening in the induction of labor

Objective. To determine the effectiveness and safety of using a double balloon catheter for cervical ripening in the induction of labor. Materials and methods. The study comprised 60 women with singleton pregnancies at ≥ 34 weeks’ gestation diagnosed with a cephalic presentation, unripe cervix (Bishop score <8), and indications for labor induction. A double balloon catheter for cervical ripening was inserted through the cervix. After 12 hours, the balloon was removed, and the patients were examined again. Depending on the Bishop score, patients underwent additional cervical ripening with either dinoprostone gel or amniotomy. If they failed to respond, induction of labor was performed by oxytocin infusion. Results. The mean gain in the Bishop score was 3. 13.3% of patients went into labor before balloon removal. The onset of labor was observed on average 3 hours after catheter removal. Sixty percent of women gave birth vaginally. The overall rate of operative delivery was 45%. Failed labor induction was observed in 18.3% of cases. All the infants were born alive. The birth weight of the newborns corresponded to the population estimates. There were no infectious complications or significant adverse effects. Conclusion. The use of the double balloon catheter is effective in cervical ripening and induction of labor at 35–41 weeks’ gestation without causing significant adverse effects on the mother or fetus.Baev O.R., Babich D.A., Shmakov R.G., Polushkina E.S., Nikolaeva A.V.

Keywords

Induction of labor is the most commonly performed obstetric interventions. At present, in developed countries, every fifth birth results from induced labor [1–3].

There are pharmacological and mechanical methods that are used to induce labor. Preparing the cervix for labor (pre-induction of labor) is important for increasing the effectiveness of labor induction. The readiness for labor is determined by cervical ripening, which traditionally evaluated using clinical scoring scales, most often the Bishop score [4, 5]. The most commonly used mechanical device for labor induction is the Foley balloon [6, 7]. The Foley balloon is inserted through the cervical canal into the uterus and then inflated with a small amount of saline exerting pressure on the internal opening of the cervix.

Despite widespread use, the Foley balloon has not been certified for preparing for labor. At the same time, in recent years, an appropriately certified double balloon catheter has been introduced into obstetric practice for cervical ripening and labor induction. The principal difference of this catheter is an additional (second) balloon, which is also inflated with saline so that it lies against the external cervical os. Thus, when using a double balloon catheter, the cervix dilation occurs simultaneously from the internal and external cervical os.

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness and safety of using a double balloon catheter for cervical ripening in the induction of labor.

Material and methods

A prospective cohort study of the efficacy and safety of using a double balloon catheter for induction of labor was conducted at the V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology of Minzdrav of Russia from September 2017 to June 2018. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee. The study was conducted by the requirements of the Helsinki Declaration (1964, 2013). All participants signed an informed consent form before taking part in the study.

The study comprised 60 pregnant women. The inclusion criteria for the study patient selection were as follows: the age of patients 18–45 years; singleton pregnancy; cephalic presentation; gestational age 34 weeks or more; an unripe cervix at the time of inclusion in the study (the Bishop score < 8); the presence of indications for induction of labor; the absence of contraindications to vaginal delivery and the use of other drugs for cervical ripening and induction of labor (mifepristone, prostaglandin E2, oxytocin); signed informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: uterine fibroids or malformations; a history of more than 3 previous cesarean deliveries; severe heart disease; arterial hypertension 160/100mm Hg and higher; severe liver, kidneys, adrenal gland dysfunction; breech fetal presentation; polyhydramnios; estimated birth weight less than 2000 g and more than 4500 g; active herpes viral infection; cervical cancer; cardiotocographic findings indicating fetal abnormalities; indications for elective cesarean delivery; premature rupture of membranes.

The women included in the study received an explanation from the investigating physician about the indications for induction of labor, the sequence of the procedure, possible complications, side effects, and outcomes. After signing informed consent, patient history taking, general and obstetric examinations, assessing the fetal condition, in the evening (7 p.m.), a double balloon catheter (Cook Cervical Ripening Balloon) was inserted through the cervix by the manufacturer’s instructions. After 12 hours, the balloon was removed, and the patients were examined again. If the Bishop score was 8 or more, amniotomy was performed, followed by uterine activity monitoring.

The onset of labor was defined as the onset of regular uterine contractions (2–3 per 10 minutes or more) with progressive smoothing and the opening of the cervix. The active phase of labor was considered achieved with complete smoothing and opening of the cervix to more than 4 cm.

In the absence of contractions within 4 hours after amniotomy, induction of labor was performed by oxytocin infusion according to our institution protocol. Uterine tachysystole was defined as 5 contractions in 10 minutes with a 30-minute interval.

The diagnosis of failed induction of labor was made if there were no uterine contractions with adequate cervical dilatation 4 hours after the initiation of oxytocin.

If after removing the balloon, the Bishop score was less than 8, a dinoprostone gel (0.5 mg) was instilled intracervically by the manufacturer’s instructions. As the Bishop score of 8 or greater was achieved, amniotomy was performed. In the absence of contractions within 4 hours after amniotomy, induction of labor was performed by oxytocin infusion.

The Bishop score of less than 6 after the dinoprostone gel instillation was regarded as a failed cervical ripening.

Before and after balloon insertion and removal, amniotomy, and continuously during oxytocin infusion and labor, fetal monitoring was performed by the cardiotocography.

Before the balloon insertion, the patient was asked to evaluate the painfulness of the procedure during the balloon insertion, exposure, and removal of the balloon using a visual analog scale (VAS) with a score range of 0 to 10. The pain was considered clinically significant if the VAS score was equal to or greater than 3.

The primary outcomes were: a change in the Bishop score after removing the balloon; the interval from balloon insertion to the onset of labor and the interval to vaginal delivery; the number of women who achieved vaginal delivery within 24 hours from the balloon insertion; the rate of failed cervical ripening and labor induction.

The secondary outcomes were: the rate and severity of painful sensations during the balloon induced cervical ripening; a delivery mode; the rate of uterine tachysystole; the need for labor induction with oxytocin; the duration of childbirth and the length of ruptured membranes; perinatal outcomes.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 20.0 statistical software package. The rates, mean values, the standard deviation, and the standard error of the mean were calculated.

Results

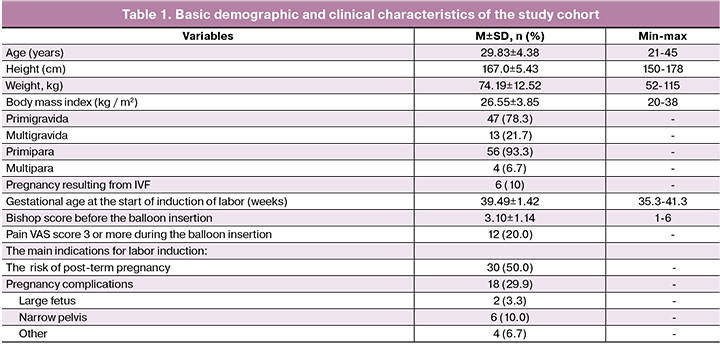

During the study period, 60 women who met the inclusion criteria, agreed to participate in the study. As follows from the data presented in table 1, the age and anthropometric characteristics of the participants corresponded to the population-based estimates. Most of the women were primiparous. Every tenth woman had a pregnancy resulting from assisted reproductive technology. Gestational age at the time of labor induction ranged from 35 weeks 3 days to 41 weeks 3 days. The gestational ages 35 - 36 weeks 6 days, 37 - 38 weeks 6 days, 39 - 40 weeks 6 days, and 41 - 41 weeks 3 days were registered in 5.1%, 23.3%, 61.6%, and 10.0% of the participants, respectively.

The Bishop cervical maturity score ranged from 1 to 6. Every fifth woman reported clinically significant discomfort and painfulness during the balloon insertion. Typically, patients experienced pain at the time of filling the balloon and during the first 3-4 hours after its insertion.

The most frequent indications for cervical ripening and labor induction were as follows: a tendency to post-term pregnancy, complicated pregnancy (preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, cholestatic hepatosis, thrombocytopenia, and fetal growth restriction), high risk of a clinically narrow pelvis during prolongation of pregnancy (anatomically narrow pelvis, large fetus) (Table. 1).

The mean gain in the Bishop score was 3 (Table 2). 13.3% of patients went into labor within 8–9 hours from the time of balloon insertion and before its removal. Four patients expelled the balloon spontaneously before the onset of labor. These observations took place in the initial stages of the study and were probably partly due to insufficient experience with balloon insertion.

In 11 cases, cervical dilation using the balloon was performed concurrently with cervical ripening using mifepristone. In 18.3% of cases, the state of the cervix after balloon removal was estimated as sufficiently ripened (Bishop score of 8 or more), and amniotomy was performed to continue the induction. In 38.3% of women cervical ripening was insufficient, and after balloon removal, they were administered cervical ripening with dinoprostone gel, followed by spontaneous labor or amniotomy. Ten percent of women did not go into labor within 4 hours after amniotomy, and they received labor induction with oxytocin.

The failure rate of cervical ripening was 10%; another 8.3% of the patients did not respond to labor induction with oxytocin. Thus, the overall failure rate of labor induction was 18.3%.

The remaining women went into labor. The onset of labor occurred on average 3 hours after balloon removal. The mean duration of labor was 8.5 hours; the length of ruptured membranes was 7 hours (Table 2). In 19 women the time from balloon insertion to vaginal delivery was less than 24 hours (figure).

The characteristics of the course of labor are presented in Table 2. Almost half of the patients required neuraxial anesthesia during labor; almost every fifth patient developed hypotonic uterine action, and acute fetal hypoxia occurred in every tenth case. There was no postpartum hemorrhage.

Sixty percent of women gave birth vaginally. Of these, three women underwent vacuum-extraction delivery due to signs of acute fetal hypoxia in the second stage of labor. The remaining women had a cesarean delivery. Indications included persistent hypotonic uterine action, clinically narrow pelvis, acute fetal hypoxia in the first stage of labor, and placental abruption. Thus, the overall rate of operative delivery was 45%.

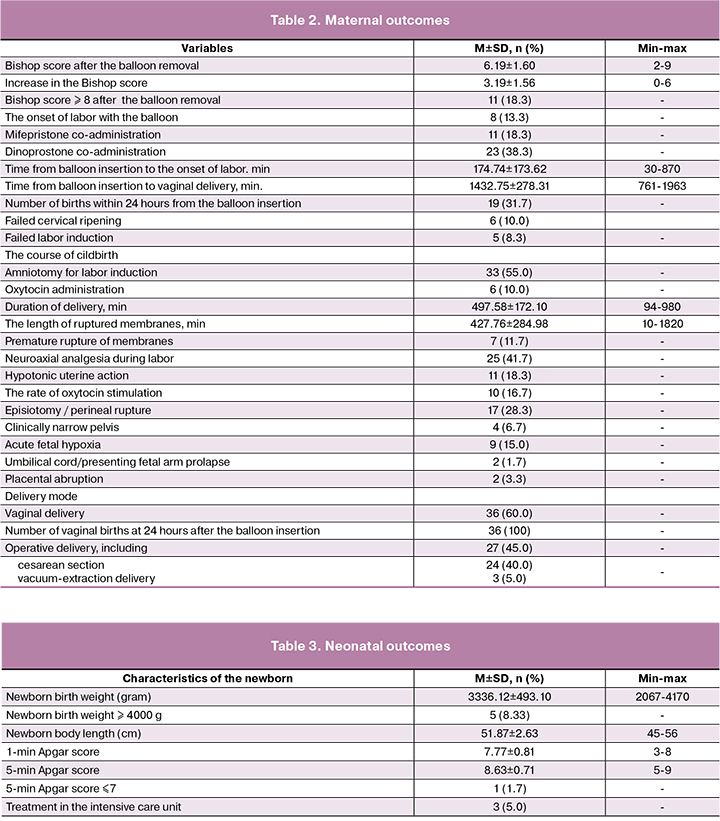

The birth weight of newborns ranged from 2067 to 4170 grams; the proportion of large fetuses was 8.3% (Table 3). Seven infants had 1-min Apgar score from 3 to 7. In three of them, 5-min Apgar scores were 5, 7 and 7. For further observation and treatment, they were transferred to the intensive care unit.

Discussion

Analysis of the study findings showed that the most commonly cervical ripening and induction of labor were used in primiparous women, and the most frequent indication was the tendency to post-term pregnancy, which is consistent with the relevant literature [8-10].

The mean gain in the Bishop score after removal of the balloon catheter was 3 [11, 12]. After removal of the balloon catheter, a complete cervical ripening according to the Bishop score was achieved in almost 20% of cases. If after removal of the balloon cervical ripening is insufficient, prostaglandins are often used. Thus, according to C. Policiano and co-authors (2017), the need for additional cervical ripening by prostaglandins was necessary in 53% of cases [10]. In our study, the intracervical dinoprostone gel was administered in 38% of cases.

As mentioned above, some women developed uterine contractions already 8-9 hours after balloon insertion. This indicates that the use of a balloon catheter in addition to the mechanical expansion of the cervical canal is accompanied by an additional effect in inducing labor. It is possible that applying mechanical pressure on the internal cervical os and stretching the lower uterine segment results in an increased local production of prostaglandin, which contributes to the activation of the uterine contractile activity. In the remaining cases, we used amniotomy (with a sufficiently ripened cervix), dinoprostone gel, or labor induction with oxytocin.

In some institutions, the use of oxytocin for induction of labor is part of the induction protocol and is used after mechanical cervical ripening or even simultaneously with the balloon [13–15]. However, those studies were aimed to assess the Foley catheter for cervical dilation. In our study, oxytocin for induction of labor was not a routine part of the protocol and was used only in 10% of cases, which indicates high effectiveness of cervical ripening using a double-balloon catheter and prostaglandin. It should be noted that we did not observe any case of uterine tachysystole, whereas in other studies its rates reached 2-3%.

In our study, the mean time from balloon insertion to the onset of labor was about 3 hours, and the duration of labor was about 8.5 hours. The mean time from balloon insertion to spontaneous delivery was slightly less than 24 hours (mean 23.9 hours). In 31% of cases, women underwent vaginal delivery within the first 24 hours after the start of cervical ripening. According to other studies, the interval from the start of labor induction to delivery ranges from 19 to 38 hours [10, 12, 16].

A hypotonic uterine action in our study was observed in 17% of pregnant women, which is consistent with the results of similar studies [16, 17]. At the same time, oxytocin for labor induction in our study was used only 10% of cases, whereas, according to other authors, it reaches 75–88% [8, 12].

According to the literature, the use of balloon catheters for induction of labor results in 66–86% vaginal delivery rates [8, 10, 12, 16]. The relatively high spontaneous delivery rate in these studies directly correlates with high rates of oxytocin stimulation. In our study, cervical ripening and labor induction resulted in vaginal delivery in 60% of cases, and the cesarean section rate was 40%.

All children of mothers participating in the study were born alive. Birth weight corresponded to the population-based values, although the large fetus rate was slightly higher. In our study, the rate of 5-min Apgar scores ≤7 was 1.7%, and the rate of newborn hospitalizations in the intensive care unit was 5%, which is consistent with data reported by other researchers, respectively, 0.3–2.0 % and 5-12% [8, 16, 18, 19].

Of seven children born with a low Apgar score, 1was born preterm, 3 had multiple fetal malformations (heart and vascular defects, diaphragmatic hernia), and 1 had an antenatal arrhythmia. Two women had a post-term pregnancy. In 1 case labor induction was used for progressive cholestatic hepatosis, in 1 for thrombocytopenia, and in three for progressive treatment-resistant arterial hypertension.

Three women underwent cervical ripening and labor induction using a balloon followed by amniotomy, 3 received a balloon and a dinoprostone gel, and one was administered sequential use of mifepristone and a balloon.

Of the seven women, five underwent an emergency Caesarean section. Indications included acute fetal hypoxia in the absence of conditions for rapid and careful vaginal delivery and placental abruption. Two patients underwent vaginal delivery; one of them had a vacuum extraction due to fetal hypoxia. Five infants were born with a tight nuchal cord.

During the study, no infectious complications and significant side effects were registered, except for mild and moderate pain at the time of balloon insertion and the first hours of its exposure. However, the rate and severity of these events were lower than in a similar study with a Foley catheter by W.A.S. Ahmed and co-authors [20, 21].

Current literature offers several definitions of the success and failure of induction of labor. Most of them are based on the vaginal delivery rate, spontaneous vaginal delivery rate, and the delivery within the first 24 hours from the start of labor induction [22–25]. At the same time, the duration of labor induction/stimulation with oxytocin, which can reach 12–15 hours, is of great importance. However, such a long time of oxytocin infusion may result in a decrease in the number of receptors in the myometrium with a loss of its sensitivity to uterotonic agents and lead to an unfavorable prognosis for the fetus and newborn due to the prolongation of the delivery time [26, 27].

Failed induction rate was 18.3% (cervical ripening 10% and labor induction 8.3%). The failure criteria included insufficient cervical ripening and ineffectiveness of oxytocin in inducing labor, which, in our opinion, most accurately reflects the failure of cervical ripening and an increased risk of further attempts to undertake conservative delivery.

Conclusion

The finding of the study showed that the use of the double balloon catheter is effective in cervical ripening and induction of labor at 35–41 weeks’ gestation without causing significant adverse effects on the mother or fetus.

References

- Chauhan S.P., Ananth C.V. Induction of labor in the United States: a critical appraisal of appropriateness and reducibility. Semin. Perinatol. 2012; 36(5): 336-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2012.04.016.

- Eikelder M.Т., Rengerink O.K., Jozwiak M., de Leeuw J.W., de Graaf I.M., van Pampus M.G. et al. Induction of labour at term with oral misoprostol versus a Foley catheter (PROBAAT-II): a multicentre randomised controlled noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2016; 387(10028): 1619-28. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00084-2.

- Mizrachi Y., Levy M., Weiner E., Bar J., Barda G., Kovo M. Pregnancy outcomes after failed cervical ripening with prostaglandin E2 followed by Foley balloon catheter. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015; 23: 1-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2015.1121477.

- Ezebialu I.U., Eke A.C., Eleje G.U., Nwachukwu C.E. Methods for assessing pre-induction cervical ripening. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015; (6): CD010762. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010762.pub2.

- Vital M., Grange J., Le Thuaut A., Dimet J., Ducarme G. Predictive factors for successful cervical ripening using a double-balloon catheter after previous cesarean delivery. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018; 142(3): 288-94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12566.

- Jozwiak M., Bloemenkamp K.W., Kelly A.J., Mol B.W., Irion O., Boulvain M. Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012; (3): CD001233. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001233.pub2.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No 579: Definition of term pregnancy.Obstet. Gynecol. 2013; 122(5): 1139-40. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000437385.88715.4a.

- Gu N., Ru T., Wang Z., Dai Y., Zheng M., Xu B. et al. Foley catheter for induction of labor at term: an open-label, randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015; 10(8): e0136856. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136856. eCollection 2015.

- Jagielska I., Kazdepka-Zieminska A., Janicki R., Formaniak J., Walentowicz-Sadlecka M., Grabiec M. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of Foley catheter pre-induction of labor. Ginekol. Pol. 2013; 84(3): 180-5.

- Policiano C., Pimenta M., Martins D., Clode N. Efficacy and safety of Foley catheter balloon for cervix priming in term pregnancy. Acta Med. Port. 2017; 30(4): 281-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.20344/amp.8003.

- Шалина Р.И., Зверева А.В., Бреусенко Л.Е., Лукашина М.В., Магнитская Н.А. Сравнительная оценка методов подготовки шейки матки к родам. Российский вестник акушера-гинеколога. 2012; 12(4): 49-54. [Shalina R.I., Zvereva A.V., Breusenko L.E., Lukashina M.V., Magnitskaya N.A. Comparative assessment of methods for preparing the cervix uteri for labor. Rossiyskiy vestnik akushera-ginekologa. Issue 4, 2012, 49-54 (in Russian)].

- Cheuk Q.K., Lo T.K., Lee C.P., Yeung A.P. Double balloon catheter for induction of labour in Chinese women with previous caesarean section: one-year experience and literature review. Hong Kong Med. J. 2015; 21(3): 243-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.12809/hkmj144404.

- Connolly K.A., Kohari K.S., Rekawek P., Smilen B.S., Miller M.R., Moshier E. et al. A randomized trial of Foley balloon induction of labor trial in nulliparas (FIAT-N). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 215(3): 392. e1-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.034.

- Mackeen A.D., Durie D.E., Lin M., Huls C.K., Qureshey E, Paglia M.J. et al. Foley plus oxytocin compared with oxytocin for induction after membrane rupture: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018; 131(1): 4-11. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002374.

- Schoen C.N., Grant G., Berghella V., Hoffman M.K., Sciscione A. Intracervical Foley catheter with and without oxytocin for labor induction. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017; 129(6): 1046-53. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002032.

- Jozwiak M., Rengerink O.K., Benthem M., van Beek E., Dijksterhuis M.G., de Graaf I.M. Foley catheter versus vaginal prostaglandin E2 gel for induction of labour at term (PROBAAT trial): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011; 378(9809): 2095-103. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61484-0.

- Baev O.R., Rumyantseva V.P., Tysyachnyu O.V., Kozlova O.A., Sukhikh G.T. Outcomes of mifepristone usage for cervical ripening and induction of labour in full-term pregnancy. Randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017; 217: 144-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.08.038.

- Dunn L., Kumar S., Beckmann M. Maternal age is a risk factor for caesarean section following induction of labour. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017; 57(4): 426-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12611.

- Mundle S., Bracken H., Khedikar V., Mulik J., Faragher B., Easterling T. et al. Foley catheterisation versus oral misoprostol for induction of labour in hypertensive women in India (INFORM): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017; 390(10095): 669-80. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31367-3.

- Sayed Ahmed W.A., Ibrahim Z.M., Ashor O.E., Mohamed M.L., Ahmed M.R., Elshahat A.M. Use of the Foley catheter versus a double balloon cervical ripening catheter in pre-induction cervical ripening in postdate primigravidae. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2016; 42(11): 1489-94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jog.13086.

- Mei-Dan E., Walfisch A., Valencia C., Hallak M. Making cervical ripening EASI: a prospective controlled comparison of single versus double balloon catheters. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014; 27(17): 1765-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2013.879704.

- Rouse D.J., Weiner S.J., Bloom S.L., Varner M.W., Spong C.Y., Ramin S.M. et al. Failed labor induction: toward an objective diagnosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011; 117(2, Pt 1): 267-72. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318207887a.

- Caughey A.B., Sundaram V., Kaimal A.J., Cheng Y.W., Gienger A., Little S.E. et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of elective induction of labor. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. (Full Rep.). 2009; (176): 1-257.

- Grobman W.A., Bailit J., Lai Y., Reddy U.M., Wapner R.J., Varner M.W. et al. Defining failed induction of labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018; 218(1): 122. e1-122. e8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.556.

- Баев О.Р., Румянцева В.П. Оптимизация подходов к применению мифепристона в подготовке к родам. Акушерство и гинекология. 2012; 6: 69-73. [Baev O.R., Rumyantseva V.P. Optimization of approaches to the use of mifepristone in preparation for childbirth. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012; 6: 69-73. (in Russian)]

- Lavoie A., McCarthy R.J., Wong C.A. The ED90 of prophylactic oxytocin infusion after delivery of the placenta during cesarean delivery in laboring compared with nonlaboring women: an up-down sequential allocation dose-response study. Anesth. Analg. 2015; 121(1): 159-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000000781.

- Balki M., Erik-Soussi M., Kingdom J., Carvalho J.C. Oxytocin pretreatment attenuates oxytocin-induced contractions in human myometrium in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2013; 119(3): 552-61. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318297d347.

Received 10.08.2018

Accepted 21.09.2018

About the Authors

Baev, Oleg R., MD, head of the 1-st Maternity Department, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov Ministry of Health of Russia, professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatology and Reproductology, Institute of Professional Educationof the I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University).

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: +74954381188. E-mail: o_baev@oparina4.ru. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8572-1971

Babich, Dmitry A., postgraduate student at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatology and Reproductology, Institute of Professional Education

of the I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University).

119991, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str. 8-2; 119991, Russia, Moscow, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya str. 2-4. Tel.: +79032950505. E-mail: babich.d@rambler.ru

Shmakov, Roman G., MD, head physician, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov Ministry

of Health of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Теl.: +74954387200. E-mail: r_shmakov@oparina4.ru

Polushkina, Evgeniya S., MD, senior researcher, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov Ministry of Health of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Теl.: +79031547413. E-mail: e_polushkina@oparina4.ru

Nikolaeva, Anastasia V., PhD, head of the 2-nd Maternity Department, , National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov Ministry of Health of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. Tel.: +74954387201. E-mail: a_nikolaeva@oparina4.ru

For citation: Baev O.R., Babich D.A., Shmakov R.G., Polushkina E.S., Nikolaeva A.V. Experience of using a double balloon catheter for cervical ripening in the induction of labor. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; (3): 64-71. (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.3.64-71