Organ-sparing surgery for postpartum endometritis after cesarean section

Objective: To present the experience of treating women who have given birth with postpartum endometritis and cesarean scar defect using a comprehensive approach. Materials and methods: This was a retrospective study of 23 case histories of patients who have just given birth. A comprehensive approach was used in the treatment of the patients which included relaparotomy, a complete excision of necrotic scar tissue, secondary sutures followed by antibacterial therapy in combination with intrauterine injection of VNIITU-1 PVP molded carbon sorbent. Results: The comprehensive approach to the treatment of patients with postpartum endometritis has been implemented since 2016. Its use has reduced the number of hysterectomies in comparison with the period 2009–2015 (OR 2.568; 95% CI: 1.19–5.5). Endometritis was diagnosed in the women on day 9.79 (6.86). All patients had an increase in the number of white blood cells to 25.1×109/L, the level of C-reactive protein to 122 mg/L; 78.3% of the patients had a change in the leukocyte formula to 25% of rod-shaped neutrophils. Such bacteria as Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Enterococcus faecium prevailed in the microflora. There was a statistically significant decrease in white blood cells, rod-shaped neutrophils, and C-reactive protein (p<0.0001) by the 5th day of administering the complex therapy. Conclusion: The use of the comprehensive approach made it possible to reduce the percentage of hysterectomies twice and contributed to the formation of a complete scar.Barinov S.V., Lazareva О.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Leont’eva N.N., Shkabarnya L.L., Chulovsky Yu.I., Gritsyuk M.N.

Keywords

Postpartum purulent-septic diseases (PSD) have been the 4th leading cause of maternal mortality over the last decade in the world due to their high prevalence and absence of a downward trend [1, 2]. Moreover, there is a growing prevalence of abdominal deliveries due to the fetal-oriented obstetric care [3]. Cesarean section could be accompanied by different complications including inflammation which is the most common one. Despite the improvement of the surgical technique, the use of modern suturing materials and antibacterial drugs, caesarean section remains a complex surgery and poses additional risks of postpartum postoperative complications [4, 5]. The incidence of endometritis after spontaneous vaginal delivery averages 2–5%, and it is 10–30% after cesarean section [6, 7]. All the subsequent purulent complications in the postpartum period occur as a consequence of progressive endometritis. The infectious process in the uterus after cesarean delivery is characterized by a more severe and prolonged course; it is accompanied by inflammatory changes in the uterine scar, which lead to its incompetence, development of peritonitis and infection [4, 5, 8].

The aim of the study is to present the experience of treating women who have given birth with postpartum endometritis and cesarean scar defect using a comprehensive approach.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective study of 23 case histories of patients who have just given birth after cesarean section; the patients were aged 25.8 (5.8) years and they were treated at the Omsk Perinatal Center of the Regional Clinical Hospital for the period from 2016 to 2020. A comprehensive approach was used in the treatment of the patients and included relaparotomy, a complete excision of necrotic scar tissue and secondary suturing; this treatment was followed by antibacterial therapy in combination with intrauterine injection of VNIITU-1 PVP molded carbon sorbent.

The analysis of obstetric and gynecological histories, characteristics of delivery and postpartum period was carried out. There was an assessment of the somatic status, the data of gynecological examination, general clinical and bacteriological studies, transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound (ultrasound), hysteroscopy.

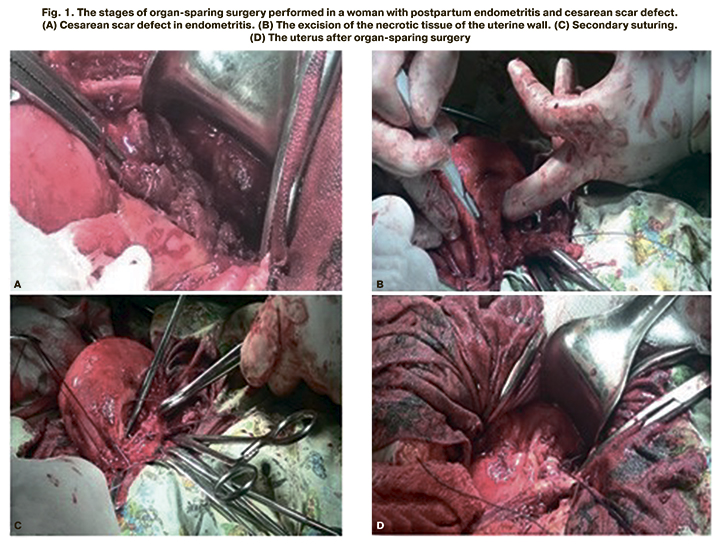

All the puerperas had a repeated surgery for the cesarean suture defect due to postpartum endometritis. The indications for performing an organ-sparing surgery were as follows: a presence of the uterine scar defect associated with postpartum endometritis with the spread of the inflammatory process not more than 2 cm above and below the scar line, absence of extensive purulent and necrotic panmetritis, absence of diffuse peritonitis. The bladder was lowered and purulent discharge was removed after relaparotomy, incision of the vesico-uterine fold. Then there was a complete excision of the altered suture on the uterus 2 cm above and below the scar line, secondary separate vicryl sutures were put (Fig. 1). If there were hematomas of the uterine scar, they were emptied; in case of parametritis and pelvioperitonitis, the drainage of parametrium and the pelvic cavity was performed with silicone tubes.

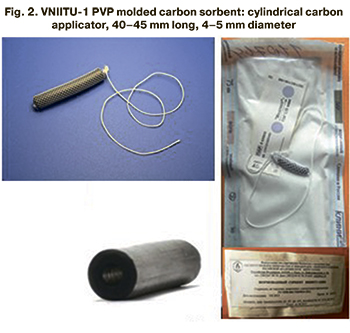

After relaparotomy the puerperas were administered antibacterial preparations, taking into account the pharmacological properties of the preparations and sensitivity of microorganisms; the therapy was approved by the clinical pharmacologist. Local treatment included intrauterine injection of sterile molded carbon sorbent VNIITU-1 modified with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) (registration certificate No. RZN 2015/2967) (Fig. 2); the injection was given intraoperatively and then the preparation was injected every 24 hours for 5 days. Molded carbon sorbent is a nanostructured mesoporous carbon material modified using PVP which absorbs pathogenic microorganisms, toxins and their waste products [9, 10]. The treatment was administered according to the protocol No. 81 of the Ethics Committee of the Omsk State Medical University dated 26.09.2016.

After relaparotomy the puerperas were administered antibacterial preparations, taking into account the pharmacological properties of the preparations and sensitivity of microorganisms; the therapy was approved by the clinical pharmacologist. Local treatment included intrauterine injection of sterile molded carbon sorbent VNIITU-1 modified with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) (registration certificate No. RZN 2015/2967) (Fig. 2); the injection was given intraoperatively and then the preparation was injected every 24 hours for 5 days. Molded carbon sorbent is a nanostructured mesoporous carbon material modified using PVP which absorbs pathogenic microorganisms, toxins and their waste products [9, 10]. The treatment was administered according to the protocol No. 81 of the Ethics Committee of the Omsk State Medical University dated 26.09.2016.

Statistical analysis

The mathematical and statistical analysis of the data was carried out using Microsoft Office Excel 2013, Statistica 10 (StatSoft Inc., USA). Qualitative indicators are presented in absolute and relative values (%). In order to assess the effectiveness of complex therapy of puerperas with postpartum endometritis and uterine scar defects, a contingency table was drawn; it presents the odds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Normal distribution of variables was determined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The arithmetic mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were calculated to describe the data with a normal distribution. The values of numerical data that are not normally distributed were described as the median (Me) and quartiles Q1 and Q3 in the format Me [Q1;Q3]. To assess the differences between the dependent samples, the Wilcoxon paired criterion was used. Taking into account the Bonferroni correction, the critical value of the significance level p is 0.017.

Results

The treatment was provided to 153 puerperas with postpartum endometritis after cesarean section during the period from 2009 to 2020 (56 women were treated from 2009 to 2015, 97 women were treated from 2016 to 2020). Total hysterectomy was performed in 19/56 (33.9%) patients from 2009 to 2015; the patients had endometritis complicated by uterine scar defect. A comprehensive approach to the treatment of postpartum endometritis has been used since 2016. From 2016 to 2020, 16/97 (16.5%) organ-resecting operations were performed. When the comprehensive approach was used in the period 2016–2020, the risk of hysterectomies was lower compared to the period 2009–2015 (OR 2.568; 95% CI 1.19–5.5).

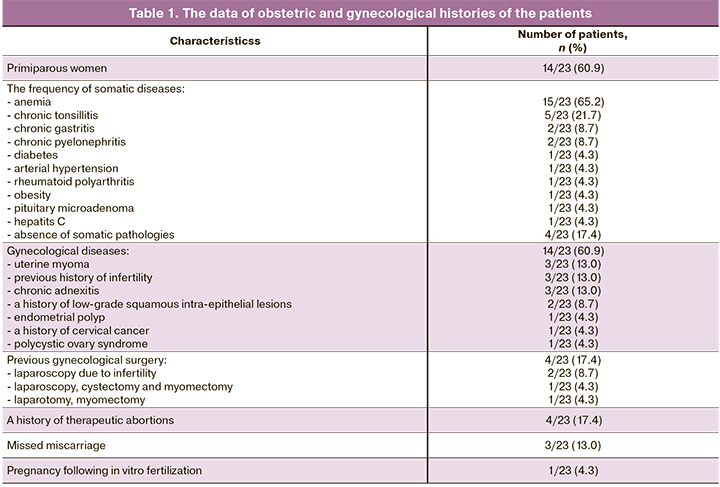

All patients were treated in the gynecological department of the Omsk Perinatal Center of the Regional Clinical Hospital. The results of the obstetric and gynecological histories are presented in Table 1. The time from the beginning of sexual activity to the first birth was 8.4 (2.6) years.

All women underwent cesarean delivery: 8/23 (34.8%) women had planned cesarean section, 15/23 (65.2%) patients had an emergency abdominal delivery. The indications for a planned surgery were the uterine scar after a previous cesarean section in 4/8 (50%) cases, fetal hypoxia during pregnancy combined with somatic pathology in 2/8 (25%) women, symphysis pubis dysfunction in 1/8 (12.5%) case, 2/8 (25%) women had moderate preeclampsia. The indications for an emergency abdominal delivery were abnormal labor in 6/15 (40%) cases, fetal hypoxia during the labor in 5/15 (33.3%) cases, cephalopelvic disproportion in 4/15 (26.7%) cases. Chorioamnionitis was noted in 3/23 (13.0%) women. Endometritis was diagnosed in puerperas on day 9.79 (6.86). All patients were transferred to the gynecological department from obstetric hospitals.

Among the clinical symptoms of endometritis, hyperthermia was observed in 19/23 (82.6%) of puerperas, and febrile temperature was noted in 15/19 (78.9%) women. The pain symptom was present in 17/23 (73.9%) patients, purulent discharge from the genital tract was in 15/23 (65.2%) patients. Uterine subinvolution was diagnosed during bimanual examination in 19/23 (82.6%) of the patients.

Complete blood analysis showed an increase in the number of white blood cells to 25.1×109/L in all puerperas. A change in the leukocyte formula to 25% of rod-shaped neutrophils was noted in 78.3% of the patients, signs of anemia were observed in 19/23 (82.6%) and thrombocytosis was observed in 11/23 (47.8%) women. All puerperas had an increased level of C-reactive protein to 122 mg/L, 17/23 (73.9%) patients had hypoproteinemia, 9/23 (39.1%) women had an increased fibrinogen level.

The ultrasound assessment revealed the signs of uterine subinvolution and hematometra in 15/23 (65.2%) patients, hematoma in the area of the postoperative suture was noted in 4/23 (17.4%) women. All puerperas underwent hysteroscopy, the results of which determined the expansion of the uterine cavity, parietal fibrin, areas of necrotic tissue, signs of hematometra.

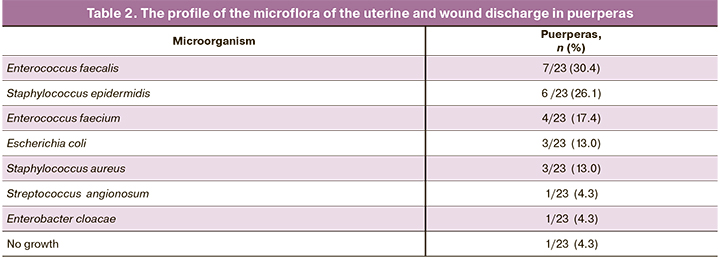

The data about the microflora of the uterine cavity found during bacteriological analysis of the uterine discharge and wound discharge are presented in Table 2.

The indications for performing relaparotomy were progressing purulent inflammation in 11/23 (47.8%) cases, hematomas of the uterine scar in 6/23 (26.1%) women, endometritis with parametritis in 2/23 (8.7%) puerperas, pelvioperitonitis in 4/23 (17.4%) cases.

According to the results of the histological study, metroendometritis with purulent-necrotic inflammation was found in all cases.

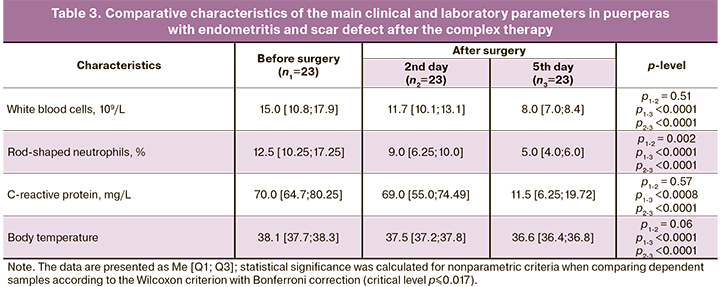

The main clinical and laboratory parameters of puerperas with endometritis and scar defects were compared when the patient was administered the complex therapy (Table 3). According to Table 3, there was a statistically significant decrease in rod-shaped neutrophils (p≤0.017) by 1.5 times on the 2nd day of treatment after organ-sparing surgery. However, there were no statistically significant decrease in body temperature and white blood cells, which was evident of an ongoing inflammatory process. There was a 1.8-fold decrease in leukocytes, 3.1–fold decrease in rod-shaped neutrophils, 4.4–fold decrease in C-reactive protein by the 5th day of treatment; the results were statistically significant in comparison with the indicators before the surgery (p<0.0001). The patients who were administered the therapy had an improvement in clinical symptoms by the 5th day of treatment: the normalization of body temperature, absence of pain symptoms and pus-like discharge from the uterus.

According to ultrasound assessment, signs of hematometra were observed in 6/23 (20.1%) women by the 2nd day; puerperas showed no changes on ultrasound examination by the 5th day of therapy. The average time of the hospital stay after relaparotomy was 11.4 (3.9) days.

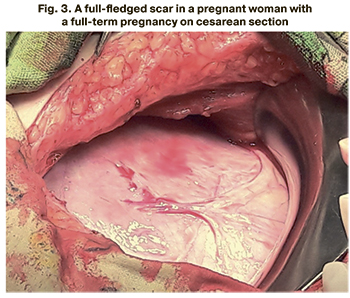

The follow-up revealed that 5/23 (21.7%) women had a full-fledged scar (Fig. 3), they became pregnant again spontaneously and had a full-term pregnancy.

The follow-up revealed that 5/23 (21.7%) women had a full-fledged scar (Fig. 3), they became pregnant again spontaneously and had a full-term pregnancy.

Discussion

Improvement of surgical technologies, development of new suture materials, use of effective broad-spectrum antibiotics made it possible to perform organ-sparing operations for postpartum endometritis and scar defect. This issue is especially relevant at the present time due to the deterioration of the health of reproductive-aged women and a decrease in the birth rate [1]. Organ-sparing operations on the uterus in the conditions of a purulent-septic process are technically complex and have a risk associated with the progression of inflammation. These operations should be performed in multidisciplinary institutions of the third level by highly qualified surgeons.

There are a few studies devoted to organ-sparing operations for postpartum endometritis and uterine scar defect, and, as a rule, a small number of patients are described [4, 6, 11, 12]. There are no results of long-term consequences and assessment of the viability of the scar. There are no clear criteria for performing such operations and the conditions of the surgery are constantly discussed [13]. In these cases, the following things should be considered: 1) timely and adequate volume of surgical intervention; 2) intensive and rational management of the postoperative period.

After an organ-sparing operation, the use of effective antibacterial therapy is obligatory. However, at present, the world has entered a post-antibiotic era, manifested by the antibiotic resistance of pathogenic microflora [1], thus it becomes necessary to find additional ways to fight infection, especially in the presence of a focus, which is an infected uterus. Since 2016 puerperas with endometritis and scar defect have been provided with postoperative treatment using not only antibacterial drugs, but also VNIITU-1 PVP molded carbon sorbent, which effectively sorbs microorganisms and their toxins from the uterine cavity. This preparation has no analogues in the world practice [9, 10].

Organ-sparing operations may not be performed in all puerperas with postpartum endometritis and uterine scar defect. The surgical intervention was not made when the inflammatory process spread more than 2 cm above and below the scar line, if the process was generalized and accompanied by the development of purulent and necrotic panmetritis as well as diffuse peritonitis. After using a comprehensive approach in the treatment of puerperas with postpartum endometritis and cesarean scar defect, there was a decrease in the number of hysterectomies from 33.9% in 2009–2015 to 16.5% in 2016–2020.

Most puerperas were primiparous women (60.9%). The time interval from the beginning of sexual activity to the first birth was 8.4 (2.6) years. There is a connection between social and medical factors. The increase of the period from the onset of sexual activity to the first pregnancy raises the risk of infectious complications which can be due to the persistence of opportunistic microflora in woman’s genital tract [1]. This fact confirms the high frequency of the prevalence of gynecological diseases in the examined women (60.9%), despite their young age.

Only 17.4% of women had no somatic diseases, despite their young age. Among all somatic diseases anemia was diagnosed more than in half (65.2%) of the cases, anemia is one of the main risk factors for the development of postpartum endometritis; anemia in combination with surgery affects the immunity increasing the risks of infectious complications after cesarean section [14, 15].

In half of the cases the uterine scar after the previous cesarean section was an indication for a planned surgery. Every cesarean section usually leads to a repeated abdominal delivery, increasing perioperative and infectious risks. In this connection World Health Organization (WHO) recommends to decrease the number of performed cesarean sections to 10–15%, taking in account the features of the medical facility and the data provided by the clinical guidelines of different countries [1, 15, 16]. Cesarean section was performed urgently in 65.2% of the cases, this significantly increases the risk of the development of postpartum endometritis [11, 18].

Clinical symptoms of endometritis developed in patients on day 9.79 (6.86) and these results are consistent with the literary data [18]. The development of postpartum endometritis and the time of the manifestation of the first symptoms are influenced by several factors including gynecological and somatic pathology, physical and neuropsychological condition of a woman, characteristics of pregnancy and labor [12, 19].

The main clinical symptom of postpartum endometritis was hyperthermia (82.6%). Subinvolution of the uterus was found during the bimanual examination in more than half of the cases (82.6%).

Complete blood test revealed leukocytosis as the main symptom, which was found in all puerperas; 78.3% of women had a shift in the leukocyte formula to rod-shaped neutrophils, which is an important indicator of the diagnosis and prognosis of postpartum endometritis [18, 20].

The ultrasound of postpartum uterus is a necessary diagnostic method. Ultrasonography makes it possible to evaluate the state of the uterus and to find hematomas. In our study the ultrasonic symptoms of subinvolution and hematometra were found in 65.2% of the puerperas. Ultrasonic symptoms of hematometra are not reliable criteria of endometritis and can be found in multiparous women, in pregnant women with a large fetus, etc. However, this sign can be valuable for the diagnosis of endometritis, when it is determined at a later stage of the postpartum period [18, 21].

Hysteroscopy of the postpartum uterus is a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure, that makes it possible to identify the form of postpartum endometritis, to visualize the state of the cesarean suture on the uterine wall, to sanitize the uterine cavity and to provide differential treatment. However, the interpretation of the hysteroscopic picture could be complicated in puerperium due to bloody discharge from the uterine cavity [18].

In most cases the bacteriological study found Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Enterococcus faecium, which are prevalent for the last 5–7 years [22–25].

Cesarean section is a significant risk factor for the development of purulent septic diseases in obstetrics because of the potential complications of the surgery [4]. The presence of hematomas in retrovesical tissue is an unfavorable symptom, that indicates the development of secondary uterine scar defect. Hematomas of the postoperative suture were found intraoperatively in 26.1% of puerperas.

There was a clinical improvement and normalization of laboratory and instrumental parameters by the 5th day of treatment after providing a comprehensive approach to the management of puerperas with postpartum endometritis and scar defect.

Conclusion

The use of the comprehensive approach to the management of puerperas with postpartum endometritis and scar defect made it possible to reduce the percentage of hysterectomies twice (from 33.9% in 2009–2015 to 16.5% in 2016–2020) and contributed to the formation of a full-fledged scar that allows women to have a full-term pregnancy in the future. The complexity of the surgical treatment of postpartum infection is determined by the repeated surgery accompanied by the inflammatory process and should be performed by highly qualified surgeons in a multidisciplinary hospital.

References

- Радзинский В.Е. Акушерская агрессия, v.2.0. М.: Медиабюро «Статус Презенс»; 2017. 872с. [Radzinsky V.E. Obstetric aggression, v.2.0. M.: StatusPraesens; 2017. 872 p. (in Russian)].

- Лебеденко Е.Ю. Near miss. На грани материнских потерь. М.: Медиабюро «Статус Презенс»; 2015. 184с. [Lebedenko E.Yu. Near miss. On the verge of maternal loss. M.: StatusPraesens; 2015. 184 p. (in Russian)].

- Радзинский В.Е., Князев С.А. Сократить долю кесаревых сечений. Настоятельные рекомендации ВОЗ о снижении доли кесаревых сечений. StatusPraesens. Гинекология. Акушерство. Бесплодный брак. 2015; 3: 11-20. [Radzinsky V.E., Knyazev S.A. Urgent recommendations of the WHO on reducing the proportion of cesarean sections. M.: Status Praesens. Gynecology. Obstetrics. A barren marriage. 2015; 3(26): 11-20 (in Russian)].

- Обоскалова Т.А., Глухов Е.Ю., Харитонов А.Н. Динамика и структура инфекционно-воспалительных заболеваний позднего послеродового периода. Уральский медицинский журнал. 2016; 5: 5-9. [Oboskalova T.A., Glukhov E.Yu., Kharitonov A.N. Dinamics and structure of inflammatory infections in late postanatal period. Ural Medical Journal. 2016; 5: 5-9. (in Russian)].

- Давыдов А.И., Подтетенев А.Д. Современный взгляд на акушерский перитонит с позиций хирургической тактики. Архив акушерства и гинекологии им. В.Ф. Снегирева. 2014; 1(1): 44-7. [Davydov A.I., Podtetenev A.D. Obstetrical peritonitis and surgical strategy: modern aspect. Archive of obstetrics and gynecology named after V.F. Snegirev. 2014; 1(1): 44-7. (in Russian)].

- Манухин И.Б., Гогсадзе И.Г., Гогсадзе Л.Г., Пономарева Ю.Н. Дифференцированная лечебная тактика у пациенток с эндометритом после кесарева сечения. Хирург. 2014; 2: 35-40. [Manuchin I.B., Gogsadze I.G., Gogsadze L.G., Ponomaryova Yu.N. Differential treatment tactics in patients with endometrial after cesarean section. The surgeon. 2014; 2: 35-40. (in Russian)].

- Tuuli M.G., Liu L., Longman R.E., Odibo A.O., Macones G.A., Cahill A.G. Infectious morbidity is higher after second-stage compared with first-stage cesareans. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014; 211(4): 410.e1-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.040.

- Братчикова О.А., Чехонацкая М.Л., Яннаева Н.Е. Ультразвуковая диагностика послеродового эндометрита (обзор). Саратовский научно-медицинский журнал. 2014; 10(1): 65-9. [Bratchikova O.A., Chekhonatskaya M.L., Yannaeva N.E. Ultrasound diagnostics of postpartum endometritis (review). Saratov Journal of Medical Scientific Research. 2014; 10(1): 65-9. (in Russian)].

- Баринов С.В., Блауман Е.С., Лазарева О.В., Долгих В.Т., Попова Л.Д., Новиков Д.С., Пьянова Л.Г. Новый метод лечения больных с послеродовым эндометритом. Российский вестник акушера-гинеколога. 2019; 19(4): 65-71. [Barinov S.V., Blauman E.S., Lazareva O.V., Dolgikh V.T., Popova L.D., Novikov D.S. et al. A new method of treatment of patients with postpartum endometritis. Russian bulletin of obstetrician-gynecologist. 2019; 19(4): 65-71. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/rosakush20191904165.

- Баринов С.В., Герунова Л.К., Тирская Ю.И., Пьянова Л.Г., Бакланова О.Н., Лихолобов В.А. Разработка углеродных сорбентов и перспективы их применения в акушерской практике. Омск: Индивидуальный предприниматель Макшеева Е.А.; 2015. 132с. [Barinov S.V., Gerunova L.K., Tirskaya Y.I., P’yanova L.G., Baklanova O.N., Likholobov V.A. The development of carbon sorbents and the perspective of their use in obstetrics. Omsk; 2015. 130 p. (in Russian)].

- Краснопольский В.И., Логутова Л.С., Буянова С.Н., Чечнева М.А., Ахвледиани К.Н. Результаты оперативной активности в современном акушерстве. Журнал акушерства и женских болезней. 2015; 64(2): 53-8. [Krasnopolskiy V.I., Logutova L.S., Buyanova S.N., Chechneva M.A., Akhvlediani K.N. Results of operative obstetrical activity in modern obstetrics. Journal of obstetrics and women’s diseases. 2015; 64(2): 53-8. (in Russian)].

- Щукина Н.А., Буянова С.Н., Чечнева М.А., Будыкина Т.С., Благина Е.А., Сибряева В.А. Органосберегающая операция у пациентки с некротическим эндометритом и несостоятельным швом на матке после кесарева сечения. Российский вестник акушера-гинеколога. 2016; 16(4): 80-4.[Shukina N.A., Buyanova S.N., Chechneva M.A., Budykina T.S., Blagina E.I., Sibryaeva V.A. Organ-sparing surgery in a patient with necrotic endometritis and an incompetent uterine scar after cesarean section. Russian bulletin of obstetrician-gynecologist. 2016; 16(4): 80-4. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/rosakush201616480-84.

- Апресян С.В., Дмитрова В.И., Слюсарева О.А. Диагностика и лечение послеродовых гнойно-септических заболеваний. Доктор.Ру. 2018; 6: 17-24. [Apresyan S.V., Dimitrova V.I., Slyusareva O.A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Postpartum Purulent Septic Diseases. Doctor.Ru. 2018; 6: 17-24. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.31550/1727-2378-2018-150-6-17-24.

- Баринов С.В., Лазарева О.В., Шкабарня Л.Л., Савкулич В.Е., Сычева А.С., Тирская Ю.И., Хорошкин Е.А., Кадцына Т.В., Медянникова И.В., Чуловский Ю.И., Безнощенко Г.Б. Клинические и диагностические критерии развития послеродового эндометрита в зависимости от метода родоразрешения. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 12: 108-16. [Barinov S.V., Lazareva O.V., Shkabarnya L.L., Savculich V.Y., Sycheva A.S., Tirskaya Y.I. et al. Clinical and diagnostic criteria for the development of postpartum endometritis depending on the method of delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020; 12: 108-16 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.12.108-116.

- Axelsson D., Brynhildsen J., Blomberg M. Postpartum infection in relation to maternal characteristics, obstetric interventions and complications. J. Perinat. Med. 2018; 46(3): 271-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2016-0389.

- Betran A.P., Torloni M.R., Zhang J.J., Gulmezoglu A.M. WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. BJOG. 2016; 123(5): 667-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13526.

- Smaill F.M., Grivell R.M. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014; (10): CD007482. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub3.

- Faure K., Dessein R., Vanderstichele S., Subtil D. Postpartum endometritis: CNGOF and SPILF Pelvic Inflammatory Diseases Guidelines. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2019; 47(5): 442-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gofs.2019.03.013.

- Callaghan W.M., Creanga A.A., Kuklina E.V. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 120(5): 1029-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5.

- Шатунова Е.П., Линева О.И., Федорина Т.А., Тарасова А.В., Лимарева Л.В., Костина Е.А. Диагностика послеродового эндометрита. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 2: 135-40. [Shatunova E.P., Lineva O.I., Fedorina T.A., Tarasova A.V., Limareva L.V., Kostina E.A. Diagnosis of postpartum endometritis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021; 2: 135-40 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.2.1358-140.

- Laifer-Narin S.L., Kwak E., Kim H., Hecht E.M., Newhouse J.H. Multimodality imaging of the postpartum or posttermination uterus: evaluation using ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2014; 43(6): 374-85. https://dx.doi.org/10.1067/j. cpradiol.2014.06.001.

- Zejnullahu V.A., Isjanovska R., Sejfija Z., Zejnullahu V.A. Surgical site infections after cesarean sections at the University Clinical Center of Kosovo: rates, microbiological profile and risk factors. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019; 19(1): 752. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4383-7.

- Самойлова Т.Е., Кохно Н.И., Докудаева Ш.А. Микробные ассоциации при послеродовом эндометрите. Русский медицинский журнал. Медицинское обозрение. 2018; 2(10): 6-13. [Samoylova T.E., Kohno N.I., Dokuchaeva S.A. Microbial association with postpartum endometritis. Russian Medical Inquiry. 2018; 2(10): 6-13. (in Russian)].

- Ahmed S., Kawaguchiya M., Ghosh S., Paul S.K., Urushibara N., Mahmud C. et al. Drug resistance and molecular epidemiology of aerobic bacteria isolated from puerperal infections in Bangladesh. Microb. Drug Resist. 2015; 21(3): 297-306. https://dx.doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2014.0219.

- Sáez-López E., Guiral E., Fernández-Orth D., Villanueva S., Gonce A., Lopez M. et al. Vaginal versus obstetric infection escherichia coli isolates among pregnant women: antimicrobial resistance and genetic virulence profile. PLoS One. 2016; 11(1): e0146531. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146531.

Received 09.06.2021

Accepted 08.07.2021

About the Authors

Sergej V. Barinov, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, barinov_omsk@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0357-7097, 644043, Russia, Omsk, Lenina str., 12.Oksana V. Lazareva, PhD., Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

lazow@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0895-4066, 644043, Russia, Omsk, Lenina str., 12.

Irina V. Medyannikova, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

mediren@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0348-5985, 644043, Russia, Omsk, Lenina str., 12.

Yuliya I. Tirskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

yulia.tirskaya@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5365-7119, 644043, Russia, Omsk, Lenina str., 12.

Tatyana V. Kadsyna, PhD, Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

tatianavlad@list.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0348-5985, 644043, Russia, Omsk, Lenina str., 12.

Natalia N. Leont’eva, PhD (Chem.), Deputy Director for Science, Center of New Chemical Technologies BIC. E-mail: science@ihcp.ru,

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-5887-5860, 644040, Russia, Omsk, Neftezavodskaya str., 54.

Lyudmila L. Sckabarnya, Head of the Department of Gynecology, Perinatal Centre of Regional Clinical Hospital, Russia, l_shka@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-6080-1828, 644011, Russia, Omsk, Beresovaya str., 3.

Yurij I. Сhulovskiy, PhD, Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

akusheromsk@rambler.ru, 644043, Russia, Omsk, Lenina str., 12.

Maxim N. Gritsyuk, Gynecologist of the Department of Gynecology, Perinatal Centre of Regional Clinical Hospital, BALEZ150284@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9166-936, 644011, Russia, Omsk, Beresovaya str., 3.

Authors’ contributions: Barinov S.V., Lazareva O.V. – developing the concept and design of the study, statistical data processing; Lazareva O.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Leont’eva N.N., Shkabarnya L.L., Gritsyuk M.N. – collecting and analyzing the material; Lazareva O.V., Kadtsyna T.V. – writing the text; Barinov S.V., Chulovsky Yu.I., Tirskaya Yu.I. – editing the article.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The article was prepared without sponsorship.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data (and associated images)

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Barinov S.V., Lazareva О.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Leont’eva N.N., Shkabarnya L.L., Chulovsky Yu.I., Gritsyuk M.N.

Organ-sparing surgery for postpartum endometritis after cesarean section.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya / Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021; 10: 76-84 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.10.76-84