Pregnancy outcomin low-weight women

Objective. To determine the prevalence of low body mass index (BMI) for pregnant women, the characteristics of their medical history, and unfavorable pregnancy outcomes and to assess the risk of unfavorable outcomes in women with low BMI.Usynina A.A., Postoev V.A., Odland J.Ø., Grzhibovsky A.M.

Subjects and methods. A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data on 57,226 births registered in the Arkhangelsk Regional Birth Registry for 2012–2015. The prevalence of sociodemographic and medical factors was investigated in singleton pregnant women with low and normal BMI. Stillbirth rates, preterm labor, a baby’s low or very low weight, five-minute Apgar scores, the need for neonatal transfer, and early neonatal death were studied as outcomes. Differences between the groups of women with low and normal BMI were determined using the Pearson’s chi-square test. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were determined by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results. Compared with women with normal BMI, in the group of mothers with a low BMI (n = 3401, 7.0% of the total number of births) there was a large proportion of primiparous, young, unemployed, smoking women, and those with a lower maternal educational level. The women with low BMI were found to have an increased risk of giving birth to a low birth weight baby.

Conclusion. Low BMI of a woman increases the risk of having a low birth weight baby.

Keywords

The prevalence of underweight among pregnant women varies in different countries reaching 15.4% [1]. It increases the risk of preterm birth [2, 3], low birth weight in infants, and fetal growth retardation syndrome [4, 5, 6]. Maternal underweight is also associated with an increased risk in anemia in newborns, perinatal mortality, and birth asphyxia [7, 8].

To date, many factors of adverse pregnancy outcomes have been studied. There is an increasing prevalence of low body mass index (BMI) among pregnant women in some countries [1]. The aim of this study was to investigate prevalence of risk factors and selected pregnancy outcomes in women with low BMI.

Materials and Methods

This study is a retrospective cohort study based on data from the Arkhangelsk County Birth Registry (ACBR) for the period 01.01.12 – 31.12.15. Of the total number of registered births (n = 57226), multiple births (n = 674), as well as births with no information on maternal weight and height (n = 551) and gestational age at the first antenatal visit (n = 609) were excluded from the study. In addition, to avoid misclassification of BMI, those with late first visit (at 12 weeks or later (n = 7362)) were also excluded. Due to the combination of exclusion criteria for the same women, the total number of births excluded from the study before the prevalence analysis (n = 9196) varies from the differences between the number of the entire population (n = 57226) and the number of births used in the prevalence analysis (n = 48554). In 13752 women, BMI was equal to 25 kg/m2 or more, and these women were also excluded from further analysis. Comparison of socio-demographic, clinical characteristics and lifestyle determinants was done for women with normal (n = 31401) and low (n = 3401) BMI.

During the first antenatal visit maternal BMI was divided into three categories: underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI = 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) (reference category), and overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2) [9].

We used each of the studied pregnancy outcomes (stillbirth, early neonatal death, preterm birth (less than 37 and 32 weeks), low and very low birth weight of the newborn, Apgar score less than 7 and 4 on the 5th minute, and the need for a neonatal transfer) as a dichotomous dependent variables.

Gestational age was assessed by obstetricians and recorded in medical documents. Low birth weight and very low birth weight in infants were defined as less than 2500 g and 1500 g, respectively. The maternal socio-demographic, lifestyle and medical characteristics, as well as perinatal outcomes were used as categorical variables. Education was considered as incomplete secondary (9 grades or less), complete secondary (10-11 grades), vocational and higher with the last category as a reference. According to marital status, we defined single mothers, women with unregistered marriages and married women (reference category). The age of the mother at the date of delivery was used as less than 18, 18-34 (reference category), and 35 years or more. Maternal occupation, smoking, evidence of alcohol abuse during pregnancy, and medical characteristics (pre-pregnancy hypertension, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia/eclampsia, spontaneous abortions, and interval between membrane rupture and delivery more than 12 hours) were represented as dichotomous variables with no/yes answers. According to the type of delivery, we classified cesarean sections and vaginal deliveries.

Chi-squared tests were employed to compare the distribution of studied independent and outcome variables between women with low or normal BMI. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined for the variables included in multivariable logistic regression. In this study, the odds ratios were used to assess relative risks, which is acceptable when the prevalence of the outcome is low (in the present study, less than 10%).

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Northern State Medical University (Arkhangelsk, Russia) (Protocol 01/02-17).

Results and Discussion

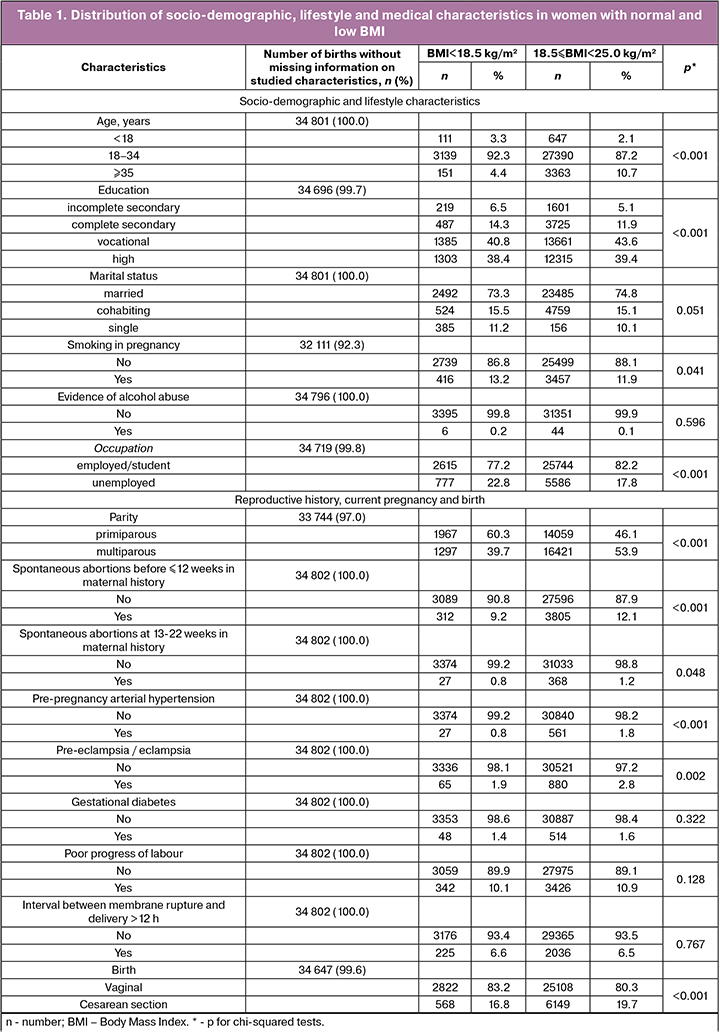

The prevalence of low BMI among 57226 women recorded in ACBR in 2012–2015 was 6.7% (n = 3794). In 551 records, information on maternal weight or height was missing. Among women with a singleton pregnancy and early antenatal visit (n = 48554), 3401 (7%) patients had a low BMI. Compared to women with normal BMI, mothers from the low BMI group were more likely to be young, primiparous, unemployed, less educated, and smoking (Table 1). The prevalence of pre-pregnancy arterial hypertension, spontaneous abortions, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, and cesarean section was lower in underweight women.

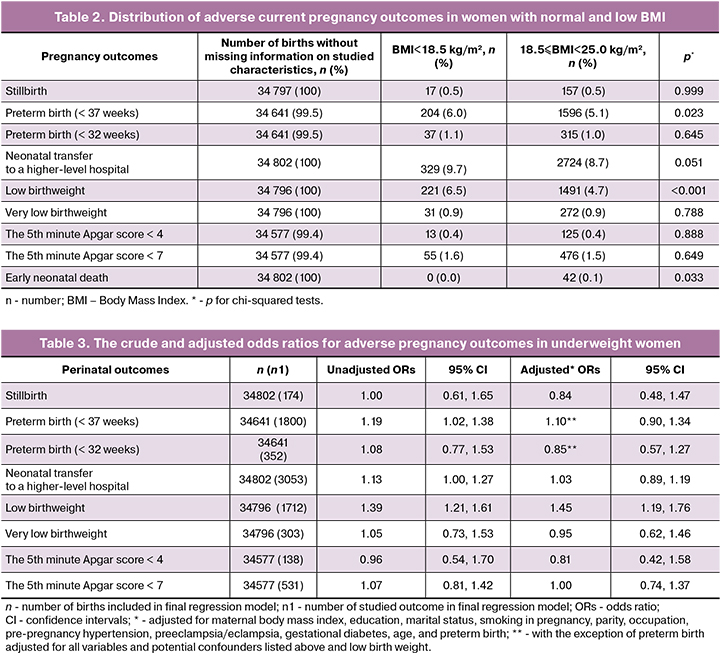

Compared to normal weight women, the proportion of preterm birth (up to 37 weeks) and low birth weight infants was higher among underweight mothers (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis showed that the risk of low birth weight was 39% higher in underweight women compared to women with normal BMI (Table 3). Low BMI was also associated with 1.2-times higher risk of preterm birth. Compared to normal BMI women, the risk of neonatal transfer to a higher-level hospital was 13% higher in underweight women. After adjusting for confounding factors, we found association between maternal underweight and increased risk of low birth weight in infants.

Our data on the higher prevalence of low BMI among primiparous women are consistent with other studies [1, 10]. Compared to other studies, we found a lower prevalence of pre-pregnancy arterial hypertension. Sebire et al. [10] demonstrated that 2.5% of women had high blood pressure before pregnancy. The discrepancy with our data can be explained by the different definition of BMI used by other researchers; they treated a value of less than 20 kg/m2 for a low BMI. Also, another method of information collection and diagnostic criteria for disease were used.

Our findings of the prevalence of low birth weight infants born to underweight mothers are also consistent with previous studies [1, 6]. Unlike our data, Suzuki [1] showed a higher prevalence of preterm birth in underweight women, that was 7.7–10.2% depending on weight gain during pregnancy. In our study, 1.4% women had a long interval between membrane rupture and delivery. It differs from data (3.4%) presented by Suzuki [1]. In our study, 6.6% of underweight women had cesarian section, lower than the studies of Suzuki (17.0%) [1], Sebire et al. (11.7%) [10], and Khan et al. (13.4%) [11].

In our study, the prevalence of gestational diabetes (1.4%) was lower compared to that (2.0%) demonstrated by others [1].

Our findings that low BMI was not associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, preterm birth, and low and very low Apgar score are consistent with other studies [10]. The lack of association between maternal underweight and increased risk of perinatal mortality, early neonatal mortality, and stillbirth was also confirmed by other researchers [11]. In contrast to our data, Khan et al. [11] did not demonstrate an increased risk of low birth weight in infants born to underweight women. Interestingly, in this study, underweight women had lower risk of preterm birth compared to the normal weight mothers. These findings contradict the results of other studies and could be explained by possible selection bias.

The registry-based study minimizes the risk of selection bias and provides generalizability of our results. The limited choice of variables and confounders in logistic regression models can be attributed to the limitations of this study. The effect of other potential risk factors (chronic diseases, complications of pregnancy, etc.) was not studied. However, our data are consistent with previously published findings of the negative effect of maternal underweight [10].

In our study, BMI was calculated during the first antenatal visit. In late antenatal visit and increased BMI, there may be a misclassification of BMI categories. Previous findings demonstrated the advantage of anthropometry in early pregnancy compared to the information on weight and height collected through interviews [12].

Conclusion

The prevalence of low BMI among pregnant women is 7%. Low maternal BMI was associated with the increased risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight. Health care providers have to consider the effect of maternal underweight on adverse pregnancy outcomes.

References

- Suzuki S. Current prevalence of and obstetric outcomes in underweight Japanese women. PLoS One. 2019; 14(6): e0218573. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218573

- Rahman M., Abe S., Kanda M., Narita S., Rahman M., Bilano V., Ota E., Gilmour S., Shibuya K. Maternal body mass index and risk of birth and maternal health outcomes in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015; 16(9): 758–70. doi: 10.1111/obr.12293.

- Scott-Pillai R, Spence D, Cardwell C, Hunter A, Holmes V. The impact of body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective study in a UK obstetric population, 2004–2011. BJOG. 2013; 120(8): 932–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12193.

- Enomoto K, Aoki S, Toma R, Fujiwara K, Sakamaki K, Hirahara F. Pregnancy outcomes based on prepregnancy body mass index in Japanese women. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0157081. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157081

- Triunfo S, Lanzone A. Impact of maternal under nutrition on obstetric outcomes. J Endocrinol Invest. 2015; 38: 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0168-4

- Liu L., Ma Y., Wang N., Lin W., Liu Y., Wen D. Maternal body mass index and risk of neonatal adverse outcomes in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019; 19: 105. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2249-z

- Mitchell M.C., Lerner E. Weight-gain and pregnancy outcome in underweight and normal weight women. JAMA. 1989; 89: 634. PMID: 2723286

- van der Spuy Z.M., Steer P.J., McCusker M., Steele S.J., Jacobs H.S. Outcome of pregnancy in underweight women after spontaneous and induced ovulation. BMJ. 1988; 296: 962–965. doi: 0.1136/bmj.296.6627.962 (Published 02 April 1988)

- BMI Classification. Global Database on Body Mass Index. World Health Organization. 2006. http://www.assessmentpsychology.com

- Sebire N.J., Jolly M., Harris J., Regan L., Robinson S. Is maternal underweight really a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome? A population-based study in London. BJOG. 2001; 108(1): 61–6. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00021.x

- Khan N., Rahman M., Shariff A.Ah., Rahman M., Rahman Sh., Rahman A. Maternal undernutrition and excessivebody weight and risk of birth and healthoutcomes. Archives of Public Health. 2017; 75: 12. doi: 10.1186/s13690-017-0181-0

- Fattah C., Farah N., Barry S.C., et al. Maternal weight and body composition in the first trimester of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010; 89: 952–5. doi:10.3109/00016341003801706

Received 15.07.2019

Accepted 04.10.2019

About the Authors

Anna A. Usynina, PhD, Cand. Sci. Med., Associate Professor at the Department of Neonatology and Perinatology, Northern State Medical University, 51 Troitsky Ave., Arkhangelsk 163000, RussiaVitaly A. Postoev, PhD, lecturer at the Department of Public Health, Health Care and Social Work, Director of the International School of Public Health, Northern State Medical University, 51 Troitsky Ave., Arkhangelsk 163000, Russia

Jon Yvind Odland, PhD, Professor at the Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, UiT The Arctic University of Norway; Professor at the Department of Global Health at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7491 Trondheim, Norway.

Andrej M. Grjibovski, PhD, Director of the Central Scientific Research Laboratory, Northern State Medical University, 51 Troitsky Ave., Arkhangelsk 163000, Russia

For citation: Usynina A.A., Postoev V.A., Odland J.Ø., Grzhibovsky A.M. Pregnancy outcomes in low-weight women.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/ Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019; 12: 90-5. (In Russian).

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.12.90-95