HELLP syndrome: preconditions for development, clinical forms, and diagnostic criteria

HELLP syndrome is associated with maternal mortality of 24.2–75% and perinatal mortality of 79‰ and is commonly regarded a severe complication of preeclampsia.Strizhakov A.N., Bogomazova I.M., Fedyunina I.A., Ignatko I.V., Timokhina E.V., Belousova V.S., Lebedev V.A., Samashov N.M.

Objective: To identify the preconditions for the development and basic laboratory criteria for different forms of HELLP syndrome to improve diagnosis and maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Materials and methods: This study retrospectively reviewed antenatal care cards and delivery notes of 22 patients with complete (n=7) and partial (n=15) HELLP syndrome. The analysis included age, medical history, specific characteristics of the course and outcome of pregnancy, and the main clinical and laboratory parameters. Quantitative variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney test; the arithmetic mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and the median difference were calculated. Binary variables are presented as counts and percentages with the effect expressed as odds ratio with 95% CI.

Results: The age of 14/22 (63.6%) patients ranged from 18 to 35 years, and 17/22 (77.3%) were multipara. HELLP syndrome developed during pregnancy and postpartum in 20/22 (90.9%) and 2/22 (9.1%) patients, respectively. Patients with the complete form of HELLP syndrome had more severe thrombocytopenia, proteinuria, and elevated levels of LDH, AST, ALT, and bilirubin. Patients with a partial form of the HELLP syndrome had more severe hypoproteinemia and higher BP. Only 1/22 (4.5%) patients with the complete form of HELLP syndrome complained of nausea and epigastric pain.

Conclusion: Preeclampsia should not be considered as a background for the development of the complete form of HELLP syndrome, because both the Zangemeister triad and the combination of arterial hypertension and proteinuria were detected only in 9/15 (60%) patients with the partial form. Complete form was characterized by a sudden decrease in platelet count with a lightning-fast increase in LDH and bilirubin against a background of patient well-being.

Keywords

HELLP syndrome is a life-threatening pregnancy complication, which ranks second in maternal mortality (14%) and occurs more frequently in primiparous women over 35 years of age with chronic cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and urinary tract diseases [1]. Endothelial dysfunction is a pathogenic mechanism in the development of preeclampsia that triggers pronounced microcirculatory dysfunction with ischemic damage to organs and tissues, leading to multiple organ failure [2].

HELLP syndrome is associated with high maternal and perinatal mortality and reaches 24.2–75% and 79‰, respectively [3]. The manifestation of HELLP syndrome usually occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy and postpartum and is characterized by a rapid deterioration in the patient's condition [4].

The main features of HELLP syndrome are intravascular hemolysis (H), elevated liver transaminases (EL) and thrombocytopenia (low platelets, LP) [5]. This symptom complex was first described by J.A. Pritchard et al. in 1954 [6], and the term "HELLP syndrome" was suggested by L. Weinstein in 1982 [7].

Pathogenesis of HELLP syndrome involves hepatocyte degeneration with the appearance of cytolytic syndrome markers (increased transaminases) and liver failure. Traditional clinical manifestations, including right upper abdominal quadrant or epigastric pain, are mediated by the formation of petechiae in the gastric mucosa and Glisson’s capsule of the liver due to disruption of protein synthesis and, among others, clotting factors [8]. Thrombocytopenia in HELLP syndrome is due to platelet consumption during disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome (DIC), and slowed processes of “lacing” from megakaryocytes due to suppression of hematopoiesis [9].

Along with severe preeclampsia, The HELLP syndrome is currently regarded as a variant of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). TMA is a clinical and morphological syndrome manifested by hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, which develops due to microcirculatory occlusion by thrombi containing aggregated platelets and fibrin. The destruction of erythrocytes by fibrin filaments results in schizocytosis, release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and hemoglobin. In the liver, hemoglobin forms complexes with alpha-2-globulin and haptoglobin. These complexes are not excreted from the body and stored within the reticuloendothelial system. This contributes, on the one hand, to preventing iron loss using its molecules for hemoglobin de novo synthesis and, on the other hand, to preventing acute renal failure due to damage to the glomerular apparatus [10].

Arteriolar and capillary thrombosis, that underlies pathogenesis of TMA, leads to hepatic artery stenosis and, as a consequence, reduced portal blood flow and ischemic liver damage [11].

Depending on the presence or absence of hemolysis, HELLP syndrome is classified into complete and partial forms [12].

Erythrocyte destruction (hemolysis), characteristic of the full form of HELLP-syndrome, occurs on the one hand, due to their transit through the constricted vessels and obstructed vessels of the microcirculatory bed, and on the other hand – as a result decrease in blood osmolarity due to increased vascular permeability and hyponatremia [13]. The main laboratory criteria of hemolysis include the presence of schistocytes (fragmented red blood cells) on the peripheral blood smear, increased concentration of LDH, total and unbound (free) bilirubin, as well as reduced haptoglobin levels [14]. Free bilirubin, which is lipophilic, penetrates the blood-brain barrier, provoking the development of neurologic symptoms [15].

According to the literature, the classic Zangemeister triad (edema, proteinuria, and arterial hypertension) is observed in HELLP syndrome only in half of cases (40–60%), which certainly complicates the timely diagnosis of this syndrome [16, 17].

This study aimed to identify the preconditions for the development and basic laboratory criteria for different forms of HELLP syndrome based on the history, course, and outcomes of pregnancy to improve diagnosis and maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Materials and methods

This study reviewed antenatal care cards and delivery notes of 22 patients with HELLP syndrome treated in the intensive care unit of the S.S. Yudin City Clinical Hospital of the Moscow HCD. Patients were divided into groups with complete (n=7) and partial (n=15) HELLP syndrome according to laboratory hemolysis criteria: elevated LDH>600 IU/L and total bilirubin >20 μmol/L, fragmented erythrocytes (schistocytes) and haptoglobin level < 35 mg/ml. Clinical evaluation included age, medical history(somatic, obstetric, and gynecological), specific characteristics of the course and outcome of pregnancy, and the main clinical and laboratory parameters.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2010 with the Statresearch add-in and SPSS Statistics. Given the small sample (n=22), the normality of the variables was not examined for normality. Continuous variables (laboratory parameters, blood pressure values) of patients complete and partial forms of HELLP were compared with a nonparametric Mann–Whitney test; arithmetic mean (M) and standard deviation (SD), and median difference were calculated. The difference in the results was considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Categorical variables are described as counts with percentage. Effect size was expressed by odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results and discussion

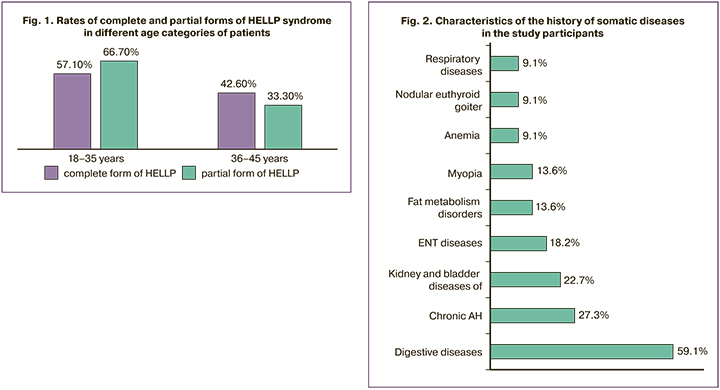

The age of the patients ranged from 18 to 45 years (mean 33±6.78). There were 14/22 (63.6%) patients aged 18-35 years, including 4/7 (57.1%) with complete and 10/15 (66.7%) with partial form of HELLP syndrome. Accordingly, there were 8/22 (36.4%) patients older than 35 years of age, of whom 3/7 (42.6%) had complete and 5/15 (33.3%) partial forms of HELLP syndrome (Fig. 1).

The HELLP syndrome was more frequently observed in young patients (18–35 years old), both with the complete (1.3-fold) and partial form (2-fold) [OR=1.500, 95% CI 0.238–9.465].

17/22 (77.3%) patients were multipara, which included all patients (7/7 (100%)) with complete and 10/15 (66.7%) patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome. Repeated pregnancies were more common in women with complete HELLP syndrome, 6/7 (85.7%), than in those with partial syndrome, 5/15 (33.3%) [OR=12.000, 95% CI 1.118–128.842].

Pregnancy following natural conception occurred in 21/22 (95.5%) patients and in 1/22 (4.5%) as a result of in vitro fertilization (IVF). In 20/22 (90.9%) patients, the pregnancy was singleton, including 6/7 (85.7%) with complete and 14/15 (93.3%) with partial form of HELLP syndrome. In 2/22 (9.1%) patients, pregnancies were multiple, represented by dichorionic diamniotic pregnancy, including 1/7 (14.3%) patients with complete and 1/15 (6.7%) with partial form of HELLP syndrome.

The characteristics of the history of somatic diseases among study patients are presented in Figure 2.

Gastrointestinal diseases (chronic gastritis, gastroduodenitis, duodenal ulcer) and hepatobiliary system (chronic pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, liver cysts) occurred 2.5-fold more often in patients with the full form of HELLP syndrome (5/7 (71.4%)) than in those with the partial form (4/15 (26.7%)) [OR=6.875, 95% DI 0.931–50.784]. On the contrary, renal disease (chronic pyelonephritis, chronic glomerulonephritis) and bladder (chronic cystitis) were detected in 5/15 (33.3%) patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome, while they were absent in patients with the full form. The incidence of chronic arterial hypertension in patients with complete [2/7 (28.6%)) and partial (4/15 (26.7%)] forms of HELLP syndrome was not statistically different [OR=1.100, 95% CI 0.149–8.125]. There were also no statistical differences in the rates of other diseases.

Complicated obstetric history was reported by 3/7 (42.9%) patients with complete and 6/15 (40%) with partial HELLP syndrome [OR=1.125, 95% CI 0.182–6.935]. A history of missed miscarriage was identified in 1/7 (14.3%) of patients with complete and in 4/15 (26.7%) of patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome [OR=2.182, 95% CI 0.197–24.209]. Spontaneous miscarriages occurred in 1/7 (14.3%) of patients with complete and 1/15 (6.7%) partial forms of HELLP syndrome [OR=2.333, 95% CI 0.124–43.795]. A history of antepartum fetal death was reported by 1/7 (14.3%) patient with a complete form of HELLP syndrome.

The gynecological history was complicated in 4/7 (57.1%) patients with complete and in 7/15 (46.7%) patients with partial HELLP syndrome [OR=1.524, 95% CI 0.250–9.295]. A history of cervical diseases was reported by 2/7 (28.6%) patients with complete form; 1/7 (14.3%) and 1/7 (14.3%) patients had secondary infertility and ovarian resection for endometrioma. Patients with the partial form had a history of cervical disease in 6/15 (40%) observations, uterine myoma in 2/15 (13.3%), endometrial polyp in 1/15 (6.7%), and ovarian resection for endometrioma in 1/15 (6.7%).

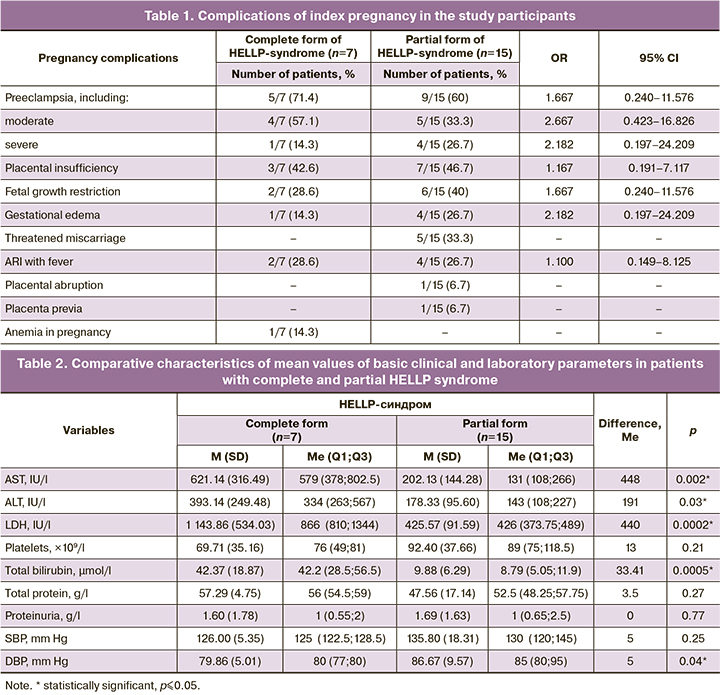

The characteristics of pregnancy complications in the study participants are presented in Table 1.

The diagnosis of preeclampsia in 4/7 (57.1%) patients with a complete form of HELLP syndrome was based on the detection of proteinuria and thrombocytopenia. Only 1/7 (14.3%) patients, along with the above symptoms, had elevated blood pressure (BP) (135/90 mm Hg).

In 2/15 (13.3%) patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome, the diagnosis of severe pre-eclampsia was based on elevated BP (160/100 and 180/100 mm Hg). In 2/15 (13.3%) other patients who had normal BP, it was based on 24-hour proteinuria (≥ 5 g/l). No proteinuria was observed in 2/15 (13.3%) patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome and moderate preeclampsia.

Elevated BP was found in 1/7 (14.3%) patients with complete and 6/15 (40%) patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome [OR=4.000, 95% CI 0.379–42.179]. Clinically significant proteinuria (≥0.3 g/l) was detected in 5/7 (71.4%) of patients with complete and 13/15 (86.7%) partial forms of HELLP syndrome [OR=2,600, 95% CI 0.284–23.815].

As also seen in the table, placental insufficiency in patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome was more often complicated by fetal growth restriction. The frequency of pregnancy complications in the two groups of patients did not differ statistically.

HELLP syndrome during pregnancy developed in 20/22 (90.9%) patients, of whom 7/22 (31.8%) had the complete and 15/22 (68.2%) partial form (ELLP syndrome). In the postpartum period, HELLP syndrome developed in 2/22 (9.1%) patients and was represented only by the partial form.

A comparison of the mean values of the main laboratory and clinical parameters revealed that patients with the complete form of HELLP syndrome had more severe thrombocytopenia, proteinuria, and elevated levels of LDH, AST, ALT, and bilirubin. At the same time, patients with a partial form of the HELLP syndrome had more severe hypoproteinemia and higher BP than those with the complete form (Table 2).

Of the complaints of nausea, vomiting, and upper abdominal pain characteristic of HELLP syndrome, only 1/22 (4.5%) multipara with dichorionic diamniotic twins and the full form of HELLP syndrome reported heartburn, nausea, and epigastric pain. The laboratory findings in this case included minor thrombocytopenia (130×109/l), increased concentration of transaminases – ALT (745 IU/l), AST (1137 IU/l), LDH (708 IU/l) and bilirubin (51 µmol/l), and hypoproteinemia (55 g/l) without proteinuria and increased BP.

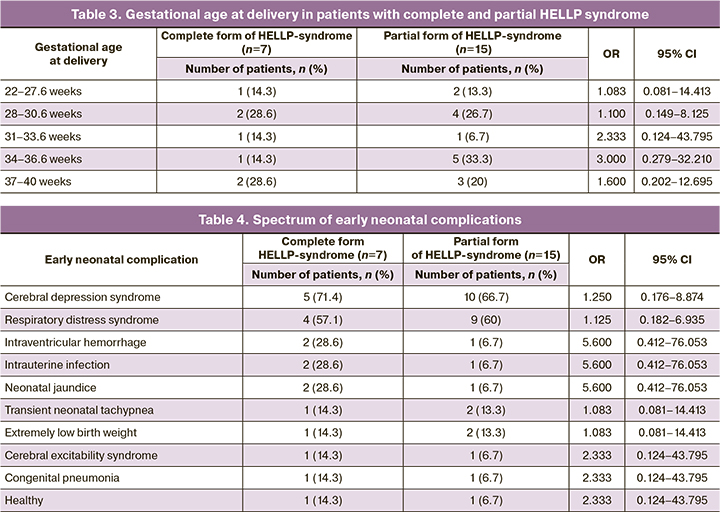

Of 22 patients, 21 (95.5%) underwent Cesarean section and 1/22 (4.5%) patient with the partial form of HELLP syndrome had vaginal delivery. Gestational age at delivery of is presented in Table 3.

Of the 23 live births, there were 14/23 (60.87%) boys and 9/23 (39.13%) girls. Boys were born more frequently in patients with the complete form of HELLP syndrome, 6/7 (85.7%), than in those with the partial form, 8/15 (53.3%) [OR=5.250, 95% CI 0.502–54.913].

One of 22 (4.5%) primiparas, who were in the 18–35 age range, had antepartum male fetal death at 29 weeks of gestation. Her pregnancy was complicated by severe preeclampsia and decompensated placental insufficiency. Given the placenta previa, the patient underwent cesarean section. On the 2nd day after delivery, a partial form of HELLP syndrome developed.

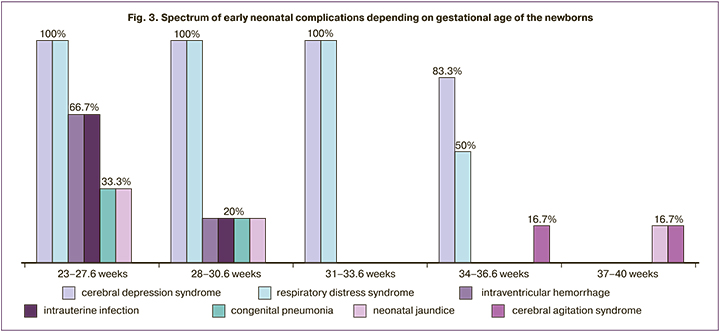

The spectrum of early neonatal complications is shown in Table 4.

Neonatal complications included cerebral depression syndrome, respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea, and extremely low body weight were due to prematurity. The rates of these complications were independent of the development of HELLP syndrome in their mothers (Fig. 3). However, such complications as intraventricular hemorrhage, intrauterine infection, congenital pneumonia, and neonatal jaundice in extremely early and early preterm births at the same age at delivery twere observed more frequently in children of patients with the complete form of HELLP syndrome.

The results of this study show that preeclampsia is more common among elderly women, while HELLP syndrome occurs predominantly in young multiparas. This may be due to the complement-associated theory of the development of gestational complications, as it is at a young age when the immunological reactivity of the body is the highest, and with each subsequent pregnancy (especially within the same marriage) there is an increase in sensitization to fetal proteins [18].

Regarding the presence of preeclampsia as a background for the development of HELLP syndrome, it was actually diagnosed in 5/7 (71.4%) observations with complete and in 9/15 (60%) with partial form. Considering the Zangemeister triad (edema, proteinuria, and arterial hypertension) among the study participants, edema was present in only 1/7 (14.3%) of patients with the full and 4/15 (26.7%) of patients with the partial form; 1/7 (14.3%) of patients with the full and 6/15 (40%) of patients with the partial form of HELLP syndrome had increased BP. Proteinuria was the most common symptom and was found in 5/7 (71.4%) of observations with complete and 13/15 (86.7%) with the partial form of HELLP syndrome. Given the fact that hypoproteinemia was more pronounced in patients with the partial form, we should assume that proteinuria was present for a longer time than in patients with the complete form of HELLP syndrome.

Analysis of transaminases in increasing order showed that patients with the complete form of HELLP syndrome initially had an increase in LDH (in combination with thrombocytopenia), followed by an increase in AST and, finally, ALT. In partial HELLP syndrome, the increase in transaminases began with an increase in ALT; the increase in AST was secondary and was not as pronounced as in the complete form. LDH and bilirubin levels in patients with the partial form did not exceed the normal range for the second half of pregnancy.

To identify the pathogenetic belonging to the increased concentration of transaminases, we calculated the de Ritis (AST/ALT) ratio, the normal range of which corresponds to 1.3–1.4. ALT is known to be a cytosolic enzyme and the preferential increase in its concentration with a decrease in the de Ritis ratio less than 1.3 is very likely indicative of liver damage (cytolysis). AST is a mitochondrial enzyme present in all organs and tissues (heart, lungs, liver, kidney, pancreas, striated muscles, etc.). Increase in its level with the increase of de Ritis coefficient above 1.4 is a marker of deep dystrophic processes accompanying development of multiple organ failure. In our study, in the partial form of HELLP syndrome, the de Ritis ratio was 1.13 (<1.3), and 1.58 (>1.4) in the complete form. This leads to the conclusion that the partial form of HELLP-syndrome is associated mainly with liver damage, while the complete form is a marker of severe multiple organ failure on the background of rapidly progressing hemolysis.

Conclusion

Although HELLP syndrome is commonly regarded as a severe complication of preeclampsia, in the present study the classic Zangemeister triad was present in only 5/15 (33.3%) patients with the partial form and in no patient with the complete form. The presence of two of the three symptoms (arterial hypertension and proteinuria) occurred in 4/15 (26.7%) observations in the partial form and none in the complete form. For this reason, pre-eclampsia should not be regarded as reliable predictor of HELLP syndrome and, in particular, its complete form.

It should also be noted that the complete form of HELLP syndrome was characterized by a certain unpredictability of its occurrence due to a sudden and rather dramatic decrease in platelet count followed by a rapid increase in LDH and bilirubin against a background of patient well-being with normal BP, no edema, and traditional complaints. It should be remembered that the detection of isolated thrombocytopenia (≤15×109/l) in the second half of pregnancy (especially in combination with nonspecific complaints, including unexplained weakness, fatigue, lack of appetite, fever, etc.) should be treated as a warning sign of developing a complete form of HELLP-syndrome. Such patients require dynamic assessment of LDH and bilirubin with the timely decision on hospitalization and preterm delivery.

Further study of the pathogenetic mechanisms of HELLP syndrome and improvement of diagnosis, prevention, and obstetric strategy will prevent severe pregnancy complications and improve maternal and perinatal outcomes.

References

- Бицадзе В.О., Макацария А.Д., Стрижаков А.Н., Червенак Ф.А., ред. Жизнеугрожающие состояния в акушерстве и перинатологии. М.: Медицинское информационное агентство; 2019. 672 с. [Bitsadze V.O., Makatsaria A.D., Strizhakov A.N., Chervenak F.A., ed. Life-threatening conditions in obstetrics and perinatology. Moscow: Medical Information Agency LLC; 2019. 672 p. (in Russian)].

- Оленев А.С., Новикова В.А., Радзинский В.Е. Преэклампсия как угрожающее жизни состояние. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 3: 48-57. [Olenev A.S., Novikova V.A., Radzinsky V.E. Preeclampsia as a life-threatening condition. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; 3: 48-57. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.48-57.

- Пырегов А.В., Шмаков Р.Г., Федорова Т.А., Юрова М.В., Рогачевский О.В., Грищук К.И., Стрельникова Е.В. Критические состояния «near miss» в акушерстве: трудности диагностики и терапии. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 3: 228-37. [Pyregov A.V., Shmakov R.G., Fеdorova Т.А., Yurova M.V., Rogachevsky О.V., Grishchuk К.А., Strelnikova E.V. Critical near-miss conditions in obstetrics: difficulties in diagnosis and therapy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; 3: 228-37. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.228-237.

- Федюнина И.А., Стрижаков А.Н., Тимохина Е.В., Асланов А.Г. Возможности неинвазивной диагностики поражения печени у беременных с преэклампсией и HELLP-синдромом. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 6: 73-9. [Fedyunina I.A., Strizhakov A.N., Timokhina E.V., Aslanov A.G. Opportunities for noninvasive diagnosis of liver damage in pregnant women with preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 6: 73-9. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.6.73-79.

- Кирсанова Т.В., Виноградова М.А., Колыванова А.И., Шмаков Р.Г. HELLP-синдром: клинико-лабораторные особенности и дисбаланс плацентарных факторов ангиогенеза. Акушерство и гинекология. 2018; 7: 46-55. [Kirsanova T.V., Vinogradova M.A., Kolyvanova A.I., Shmakov R.G. HELLP syndrome: its clinical and laboratory features and imbalance of placental angiogenic factors. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; 7: 46-55. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2018.7.46-55.

- Pritchard J.A., Weisman R., Ratnoff O.D., Vosburgh G.J. Intravascular hemolysis, thrombocytopenia and other hematologic abnormalities associated with severe toxemia of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1954; 250: 89-98.

- Weinstein L. Syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count: a severe consequence of hypertension in pregnancy. 1982; 142(2): 159-67. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32330-4.

- Хлестова Г.В., Карапетян А.О., Шакая М.Н., Романов А.Ю., Баев О.Р. Материнские и перинатальные исходы при ранней и поздней преэклампсии. Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 6: 41-7. [Khlestova G.V., Karapetyan A.O., Shakaya M.N., Romanov A.Yu., Baev O.R. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in early and late preeclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017; 6: 41-7. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.6.41-7.

- Стрижаков А.Н., Тимохина Е.В., Федюнина И.А., Игнатко И.В., Асланов А.Г., Богомазова И.М. Почему преэклампсия трансформируется в hellp-синдром? Роль системы комплемента. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 5: 52-7. [Strizhakov A.N., Timokhina E.V., Fedyunina I.A., Ignatko I.V., Aslanov A.G., Bogomazova I.M. Why does preeclampsia transform into hellp syndrome? the role of the complement system. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; 5: 52-7. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.5.52-57.

- Кирсанова Т.В., Виноградова М.А., Федорова Т.А. Имитаторы тяжелой преэклампсии и HELLP-синдрома: различные виды тромботической микроангиопатии, ассоциированной с беременностью. Акушерство и гинекология. 2016; 12: 5-14. [Kirsanova T.V., Vinogradova M.A., Fedorova T.A. The imitators of severe preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome: Different types of pregnancy-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016; 12: 5-14. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2016.12.5-14.

- Findeklee S. Fallbericht Leberruptur bei fulminantem HELLP-Syndrom in der 37. SSW. Z. Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2018; 222(5): 212-6. (in German). https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/a-0631-9631.

- Калачин К.А., Пырегов А.В., Федорова Т.А., Грищук К.И., Шмаков Р.Г. «Нетипичный» HELLP-синдром или атипичный гемолитико-уремический синдром? Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 1: 94-102. [Kalachin K.A., Pyregov A.V., Fedorova T.A., Grishchuk K.I., Shmakov R.G. Atypical HELLP syndrome or atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome? Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017; 1: 94-102. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.1.94-102.

- Макацария А.Д., Бицадзе В.О., Хизроева Д.Х., Акиньшина С.В. Тромботические микроангиопатии в акушерской практике. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2017. 304с. [Makatsaria A.D., Bitsadze V.O., Khizroeva D.H., Akinshina S.V. Thrombotic microangiopathies in obstetric practice. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2017. 304 p. (in Russian)].

- Куликов А.В., Шифман Е.М., ред. Анестезия, интенсивная терапия и реанимация в акушерстве и гинекологии. Клинические рекомендации. Протоколы лечения. 2-е изд. М.: Медицина; 2017. 688с. [Kulikov A.V., Shifman E.M., ed. Anesthesia, intensive care and resuscitation in obstetrics and gynecology. Clinical recommendations. Treatment protocols. The second edition, supplemented and revised. M.: Publishing House "Medicine"; 2017. 688 p. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18821/9785225100384.

- Findeklee S., Costa S.D., Tchaikovski S.N. Thrombophilie und HELLP-Syndrom in der Schwangerschaft – Fallbericht und Literaturübersicht. Z. Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2015; 219(1): 45-51. (in German). https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1385856.

- Trávniková M., Gumulec J., Kořístek Z., Navrátil M., Janáč M., Pelková J., Šuráň P. et al. HELLP syndrom vyžadující plazmaferézu pro rozvoj multiorgánové dysfunkce s dominující encefalopatií, respirační a renální insuficiencí. Ceska Gynekol. 2017; 82(3): 202-5. (in Czech.).

- Стрижаков А.Н., Линева О.И., ред. Беременность и патология печени. Медконгресс; 2022. 160с. [Strizhakov A.N., Lineva O.I., ed. Pregnancy and liver pathology. 2022. 160 p. (in Russian)].

- Сидорова И.С. Преэклампсия. М.: Медицинское информационное агентство; 2016. 528с. [Sidorova I.S. Preeclampsia. M.: LLC "Publishing House "Medical Information Agency", 2016. 528 p. (in Russian)].

Received 17.03.2022

Accepted 20.04.2022

About the Authors

Alexander N. Strizhakov, Dr. Med. Sci., Academician of the RAS, Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), +7(499)782-30-45, strizhakov_a_n@staff.sechenov.ru, 119991, Russian Federation, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-2.Irina M. Bogomazova, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), +7(499)782-30-45, +7(926)305-04-03, bogomazova_i_m@staff.sechenov.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1156-7726, 119991, Russian Federation, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-2.

Irina A. Fedyunina, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute of Clinical Medicine,

I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), +7(499)782-30-45, fedyunina_i_a@staff.sechenov.ru, 119991, Russian Federation, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-2.

Irina V. Ignatko, Dr. Med. Sci., Corresponding Member of the RAS, Professor of the RAS, Professor, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

(Sechenov University), +7(499)782-30-45, kafedra-agp@mail.ru, 119991, Russian Federation, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-2.

Elena V. Timokhina, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute

of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), +7(499)782-30-45,

timokhina_e_v@staff.sechenov.ru, 119991, Russian Federation, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-2.

Vera S. Belousova, Dr. Med. Sci., Associate Professor, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute

of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), +7(499)782-30-45,

belousova_v_s@staff.sechenov.ru, 119991, Russian Federation, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-2.

Vladimir A. Lebedev, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the N.V. Sklifosovsky Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), +7(499)782-30-45, lebedev_v_a@staff.sechenov.ru, 119991, Russian Federation, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-2.

Nikolay M. Samashov, Obstetrician-Gynecologist at the maternity ward of the Maternity Hospital, S.S. Yudin City Clinical Hospital of the Moscow City Health Department, +7(499)782-30-64, NikolaySamashov9@mail.ru, 115446, Russian Federation, Moscow, Kolomensky proezd, 4.

Corresponding author: Irina M. Bogomazova, bogomazova_i_m@staff.sechenov.ru

Authors' contributions: Strizhakov A.N., Ignatko I.V., Timokhina E.V., Belousova V.S., Lebedev V.A. – conception and design of the study; Bogomazova I.M., Samashov N.M. – data collection and analysis; Bogomazova I.M., Fedyunina I.A. – statistical analysis; Bogomazova I.M., Fedyunina I.A., Samashov N.M. – manuscript drafting; Strizhakov A.N., Ignatko I.V., Timohina E.V., Belousova V.S., Lebedev V.A. – manuscript editing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University) (Extract from the minutes of the REC meeting of 30.06.2017).

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Strizhakov A.N., Bogomazova I.M., Fedyunina I.A., Ignatko I.V.,

Timokhina E.V., Belousova V.S., Lebedev V.A., Samashov N.M. HELLP syndrome:

preconditions for development, clinical forms, and diagnostic criteria.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 5: 65-73 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.5.65-73