High-risk pregnancy and perinatal losses

Objective. To evaluate the effectiveness of predicting perinatal losses, by applying the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” drawn up more than 40 years ago.Bezhenar V.F., Ivanova L.A., Grigoryev S.G.

Subjects and methods. A case control study to assess risk factors was conducted in 664 pregnant women. A study group consisted of 307 women with perinatal losses (antenatal (n = 159) and intrapartum (n = 49) fetal deaths; 99 newborns died in the first 168 hours of life). A control group included 357 (53.8%) women without perinatal losses.

Results. Analysis of socio-biological factors, obstetric/gynecological histories, and maternal extragenital pathology revealed no statistically significant differences in the comparison groups. Noise factors made the assessment of the risk for the course of pregnancy difficult.

Conclusion. The table-based prognostic model has low sensitivity and is unable to identify a group at high risk for perinatal losses.

Keywords

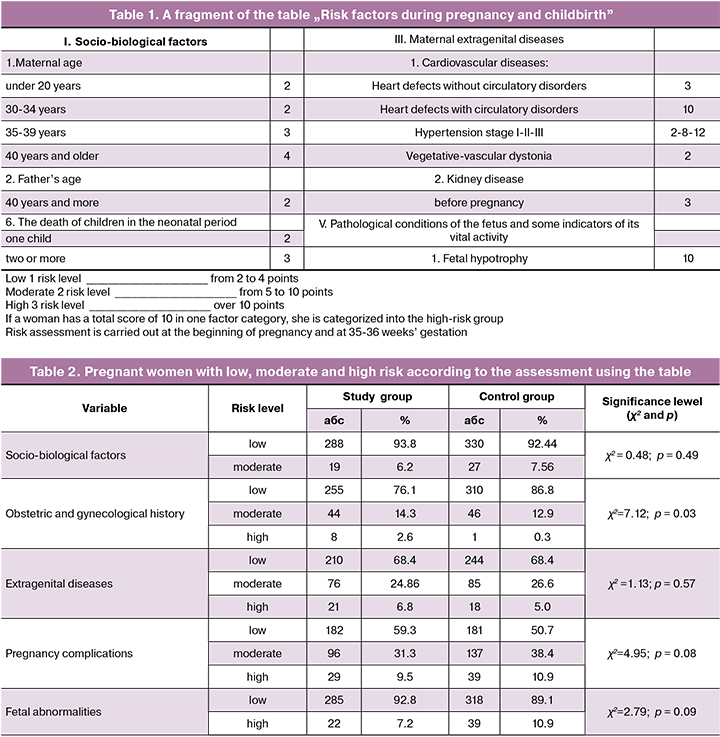

Over the last ten years, the perinatal mortality rate in the Russian Federation (RF) has been on a clear downward trend, reaching a record low of 7.34 ‰ in 2016, and then slightly increasing in 2017 to 7.5 ‰. However, in some constituent entities of the Russian Federation (Bryansk, Novgorod, Vologda regions, the republics of Ingushetia, Mari El, Trans-Baikal, and Khabarovsk territories, the Jewish Autonomous Region and the Chukotka Autonomous Region), these figures exceeded 10 ‰ [1]. For many years in the Russian Federation, the concept of high-risk pregnancy has been recognized as both perinatal losses and maternal mortality [2]. Social status, medical history, pregnancy course, and other indicators are included in the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” (Table 1), which has been widely used by obstetricians-gynecologists of antenatal clinics, filling out special forms and recording the obstetric data on the Medical Card of the Pregnant Woman (f. No. 113 / U). The use of the scale “Scoring of prenatal risk factor” for the quantitative assessment of risk factors was first regulated by Order No. 430 of the Ministry of Health of the USSR of 04/22/1981; further, the prenatal risk factors were listed in Order No. 50 of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation of 02/10/2002. The table is intended to identify a group of women with a high-risk pregnancy. One of the most severe pregnancy outcomes is perinatal death. We analyzed the feasibility of predicting perinatal losses using the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth.”

This study aimed to investigate the feasibility of predicting perinatal losses using the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth.”

Materials and methods

The retrospective analysis was based on data obtained from the Medical Card of the Pregnant Woman (f. No. 113 / U) or delivery notes (for puerperal women who were not registered in the antenatal clinic). Monitoring of perinatal losses in puerperas discharged from maternity hospitals on days 3-5 was carried out by telephone survey of the child’s health status. Criteria for exclusion from the study were multiple-gestation pregnancy and inability to assess risk factors due to lack of data. For all patients, the standard table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” was filled out, and a total score was calculated by summing together all the risk factor scores. Further analysis included only on risk scores, i.e., mean values for each patient, frequency of occurrence in the study and control groups, etc. were not taken into account. Each parameter (disease) was assigned the exact score that was provided for in the table.

The sample size was not predetermined. Statistical analysis was performed using the STATISTICA 7 software (Statsoft Inc., USA). Quantitative variables were expressed as means and standard deviation. Comparing numerical data between groups was performed with the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were compared by the Pearson χ2 test. The critical level of significance when testing statistical hypotheses was considered at p < 0.05. Logistic regression models were generated for predicting perinatal losses. The model was statistically significant with not less than 95% reliability (p < 0.05), as well as with diagnostic accuracy (relative frequency of the correct assignment of objects to the group of observations) of 70% or more. To assess the relationship between the predicted variable and the features included in the model, the odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results

The distinctive feature of using the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” is the assessment of parameters strictly as scores, without taking into account quantitative indicators. That is, all signs, including quantitative ones, are first transformed into qualitative ones (for example, age 36 corresponds to the group “age 35–39 years”), and then each group is assigned a score (“age 35–39 years” is scored as 3 points). Thus, the analyzed parameters were assigned to a specified category, scored (from 1 to 12), after which the risk category (low, medium and high) was determined, following the recommendations of the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” (table. 2).

The table includes some indicators that are ambiguous and difficult for an obstetrician-gynecologist to estimate. For example, the risk factor “emotional stress,” which is likely to be reported by every modern woman, was not noted by any doctor in any pregnant woman in our study. This indicator was excluded from the analysis. Similarly, we excluded from the analysis the indicator “neurological disorders in children,” which is difficult to assess. What exactly should be reflected in this paragraph for the obstetrician-gynecologist is not entirely clear: severe neurological disorders, hereditary neurological syndromes, cerebral palsy, which are rare (in our study, were not noted) or perinatal encephalopathy (a diagnosis that is established for almost all children). As a result of such discrepancies, many doctors fill this item very rarely, while some other doctors register it in all multiparous women.

Discussion

Over the 40 years since the development of the initial version [2] of the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” (Table 1), it has been slightly changed. In most cases, a risk score is currently presented as a specific figure, rather than an interval. For example, a history of occupational hazards was initially estimated at 1–4 points, now - at 2 points. Some indicators were excluded from the table: maternal age - 25–29 years, father’s age - 20 years, mother’s primary and higher education, marital status – “unmarried woman” in the section “Socio-biological risk factors.” However, the list of socio-biological risk factors does not include a registered marriage, permanent official employment, and drug addiction. As for height and weight indicators, the concept of “weight 25% more than normal” is not used (it was determined additionally); weight and height can be more accurately assessed using the body mass index.

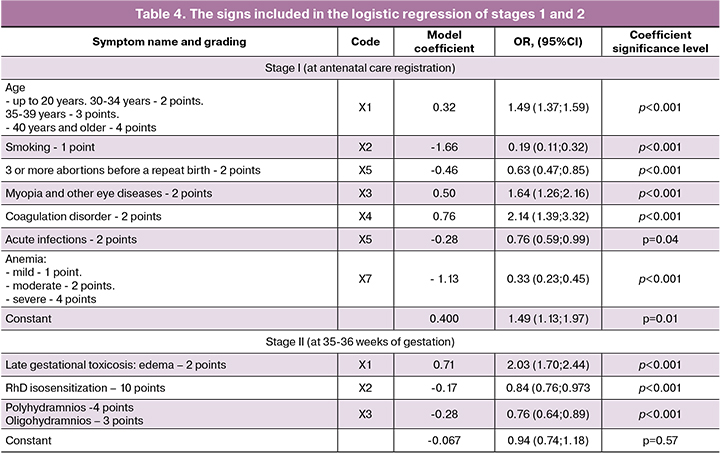

We aimed to assess the feasibility of predicting perinatal losses as a special case of a “high-risk pregnancy” and obtained unexpected results: in pregnant women in the study and control groups, the distribution among low-medium-high-risk groups has no statistical differences. How could that be explained? The number of indicators was registered statistically significantly more often in the control group, including maternal and father’s age among socio-biological risk factors, eye diseases, and coagulopathies among extragenital conditions (Table 4). Besides, there are plenty of “noise” factors that do not have statistically significant differences in patients of both groups (kidney disease, specific infections). As a result, the factors that may indeed increase the risk of perinatal losses (smoking, a history of preterm delivery, anemia) are leveled (Table 4). As regards cardiovascular diseases, the table includes their comprehensive assessment; as a result, heart defects without circulatory disorders (for example, mitral valve prolapse) were scored at 3, and stage I hypertension was scored at 2, the same as vegetative-vascular dystonia. As a result of such an assessment, hypertension, including stage II – III stage, which was statistically significantly more common in the study group, was “balanced” by vegetative-vascular dystonia by the hypotonic and cardiac type, which was statistically significantly more often diagnosed in the control group.

The paragraph “chronic specific infections” indicates toxoplasmosis; however, currently, it is believed that detection of class G immunoglobulins in the first half of pregnancy is diagnostic for toxoplasmosis, which does not require further observation and treatment [3]. That is, in this assessment system, active hepatitis C and carriage of a class G immunoglobulin to Toxoplasma gondii have the same risk score for perinatal losses. Another item that most likely needs to be reviewed is “myopia and other eye diseases.” Forty years ago, high myopia with myopia-related fundus abnormalities demanded to avoid pushing after the onset of the labor, for which the application of obstetric forceps was most often used, which, in theory, could lead to an increase in perinatal losses. Currently, the relationship between myopia and perinatal losses is questionable [4].

The assessment of pregnancy complications is associated with many problems that often make it impossible to use these risk factors at 35–36 weeks’ gestation by antenatal care clinicians. These risk factors can be used only at the stage of the obstetric care facility. So, everything is clear with bleeding in the first half of pregnancy: a spontaneous miscarriage successfully treated at its initial stages with maintenance therapy, increases the risk of perinatal losses, estimated in the III trimester. But bleeding in the second half of pregnancy is unlikely to managed by , the obstetrician-gynecologist of the antenatal clinic, because if this bleeding is caused by placenta previa, the pregnant woman will be hospitalized until delivery; bleeding due to placental abruption in most cases requires emergency delivery. Accordingly, the higher score in the column “bleeding in the second half of pregnancy” is associated with a statistically significantly higher incidence of placental abruption, which required emergency delivery, often up to 35-36 weeks. Therefore, in real life antenatal care clinicians will not be able to do this assessment. There is a similar situation with the item “fetal breech presentation”. In the study group, births with breech presentation were statistically significantly more common, which is most likely associated with a higher incidence of breech presentation in preterm births, especially before 28 weeks, compared with term deliveries. Therefore, this parameter is an intranatal risk factor, not an antenatal one. It is also not clear how antenatal care clinicians can evaluate the parameter “prolonged gestation” at 35–36 weeks.

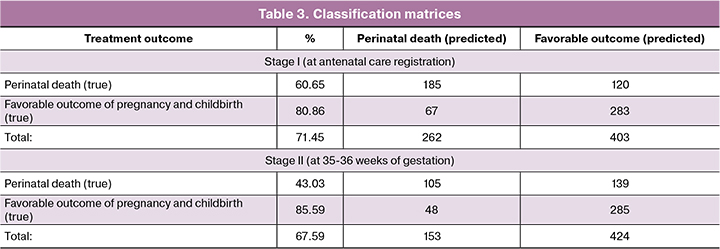

Given the above facts, we decided to assess the feasibility of using the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” to classify pregnant women into an isolated group of women at high risk of perinatal losses. To assess this possibility, a multivariate logistic regression model was constructed, which is used for statistical analysis to estimate the probability of assigning a particular patient to one of the compared groups. The method is intended to determine the likelihood of an outcome (dependent variable) based on a set of independent variables (predictors). Concerning the study table, we constructed two separate logistic regression models - according to the number of stages carried out by the antenatal care physician: when registering (social history factors, obstetric and gynecological history, and maternal extragenital diseases) and at 35-36 weeks’ gestation (pregnancy complications and fetal abnormalities). All signs were set according to their recommended scores, i.e., as quantitative variables. Logistic regression reveals whether a particular symptom listed in the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” increases or decreases the likelihood of a positive (the neonate will survive the perinatal period) or negative (the neonate will not survive) presenting results as odds ratios (OS). The statistical analysis showed that at stage I, only 7 out of 35 signs from the table, which can be evaluated at the time of registration at an antenatal clinic, have a statistically significant effect on perinatal outcomes, increasing (decreasing) the risk of perinatal losses by 1,3-5 times.

At the second stage of the assessment (at 35–36 weeks’ gestation), only 3 out of 12 signs from the table have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of perinatal losses (increase/decrease the risk by a factor).

Both constructed logistic regression models were statistically significant (p <0.001) and the models have a predictive value of about 70% due to the high specificity of 81–86% (the ability to predict the absence of perinatal losses), but low sensitivity 43–61% (the ability to predict perinatal death). Classification matrices are presented in the table. 3.

The variables included in the logistic regression are presented in the table. 4. The units of measurement of all signs were scores. Odds ratios (OR) are presented with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

The findings of our analysis of factors that have been used to identify high-risk pregnancies for more than 40 years suggest that most of them have no predictive value for predicting a high risk of perinatal losses. Of the 47 assessed factors, only 10 had statistical significance. The factors included in the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” are predictive for perinatal losses with high specificity (more than 80%) but low sensitivity (the ability to predict perinatal death) 40-60%. Therefore, currently, there are no tools that may help the obstetrician-gynecologist to predict perinatal losses accurately.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study suggest that the table “Risk factors during pregnancy and childbirth” is not designed to predict perinatal losses, as it was initially created to determine the risk group. To predict the likelihood of perinatal losses, it is necessary to develop a new prognostic model with higher sensitivity and sufficient specificity based on statistically significant factors.

References

- Демографический ежегодник России. Официальное издание. М.: Федеральная служба государственной статистики, 2017. 263. [Demographic Yearbook of Russia. The official publication. M. Federal State Statistics Service, 2017. 263 p. (in Russian)]

- Абрамченко В.В. Беременность и роды высокого риска. М.: МИА, 2004. 400. [Abramchenko V.V. High-risk pregnancy and labor. M.: MIA, 2004.400 p. (in Russian)]

- Никитина Е.В., Гомон Е.С., Иванова М.А. Токсоплазмоз и беременность. Охрана материнства и детства. 2014; 2: 75–9. [Nikitina Ye.V., Gomon Ye.S., Ivanova M.A. Toxoplasmosis and pregnancy. Okhrana materinstva i detstva/Protection of motherhood and childhood. 2014; 2: 75–9. (in Russian)]

- Танцурова К.С., Попова М.Ю., Кухтик С.Ю., Фортыгина Ю.А. Тактика ведения беременных с миопией (литературный обзор). Вестник совета молодых ученых и специалистов Челябинской области. 2016; 3 (14) (4): 86–8. [Tantsurova K.S., Popova M.YU., Kukhtik S.YU., FortyginaYU.A. Management tactics for pregnant women with myopia (literature review). Vestnik soveta molodykh uchenykh i spetsialistov Chelyabinskoy oblasti/Bulletin of the Council of Young Scientists and Specialists of the Chelyabinsk Region.2016; 3 (14) (4): 86-88. (in Russian)]

Received 22.10.2019

Accepted 29.11.2019

About the Authors

Vitaliy F. Bezhenar, MD, professor, head of the department of obstetrics, gynecology and neonatology FSBEI HE First St. Petersburg State Medical University namedafter academician I.P. Pavlov Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.:+7 (812) 338 7866. E-mail: bez-vitaly@yandex.ru. ORCID ID: 0000-0002-7807-4929

197022, St. Petersburg, ul. Leo Tolstoy, 6-8.

Lidiya A. Ivanova, candidate of medical sciences, associate professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Federal State Medical University Military Medical Academy named after CM. Kirov of the RF Ministry of Defense. Tel.:+7 (812) 667-71-46. E-mail: lida.ivanova@gmail.com ORCID ID: 0000-0001-6823-3394

194044, St. Petersburg, ul. Academician Lebedev, d.6.

Stepan G. Grigorev, MD, professor, senior researcher at the research center of the FSBEI Military Medical Academy named after CM. Kirov of the RF Ministry of Defense. Tel.:+7 (812) 2923479. E-mail: gsg_rjj@mail.ru ORCID ID: 0000-0003-1095-1216

194044, St. Petersburg, ul. Academician Lebedev, d.6

For citation: Bezhenar V.F., Ivanova L.A., Grigoryev S.G. High-risk pregnancy and perinatal losses.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/ Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020; 3: 42-7.(In Russian).

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.42-47