Clinical value of B-type natriuretic peptide levels in umbilical cord blood in fetal growth restriction and normal pregnancy

Seurko K.I., Timokhina E.V., Ignatko I.V., Sarakhova D.Kh., Titov V.A., Seurko K.I., Saykina A.V., Kardanova M.A.

Objective: To evaluate B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels in fetal umbilical cord blood as a potential biomarker of fetal status in normal pregnancies and in pregnancies with early- and late-onset fetal growth restriction (FGR). Additionally, we analyzed perinatal outcomes in newborns with FGR compared to those with normal growth and weight indicators.

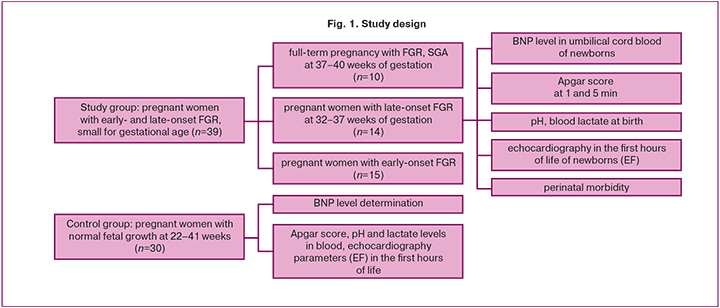

Materials and methods: A prospective study was conducted involving 39 pregnant women with early- and late-onset FGR (study group) and 30 pregnant women with uncomplicated pregnancies (control group), matched for gestational age. Umbilical cord blood samples were collected at the time of birth. The study group was divided into three subgroups: subgroup IA comprised 10 patients with FGR at term (37–40 weeks); subgroup IB included 15 patients with early FGR (<32 weeks); and subgroup IC included 14 patients with late-onset FGR (32–37 weeks).

Results: The mean serum brain BNP level was significantly higher in the umbilical cord blood of newborns with FGR across all study groups than in the control group. In subgroup IA, the mean was 1161 [537; 1635] pg/ml versus 551 [457; 781] pg/ml; in subgroup IB, it was 13 570 [11 773; 17 979] pg/ml versus 1699 [1396; 2377] pg/ml (p<0.05); and in subgroup IC, it was 1551 [1283; 2231] pg/ml versus 1344 [892; 1496] pg/ml (p<0.05).

Conclusion: Mean brain BNP levels in fetal umbilical cord blood were elevated in newborns with FGR compared to those with normal fetal growth. Furthermore, brain BNP levels are significantly higher in cases of early-onset FGR than in those of late-onset FGR.

Authors' contributions: Ignatko I.V., Seurko K.I., Timokhina E.V. – conception and design of the study; Seurko K.I., Titov V.A., Sarakhova D.Kh. – data collection and analysis; Seurko K.I., Saykina A.V., Kardanova M.A. – statistical analysis; Seurko K.I., Seurko K.I., Titov V.A. – drafting of the manuscript; Ignatko I.V., Timokhina E.V., Sarakhova D.Kh. – editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University) (Ref. No: 28-24 of November 2025).

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Seurko K.I., Timokhina E.V., Ignatko I.V., Sarakhova D.Kh., Titov V.A., Seurko K.I., Saykina A.V., Kardanova M.A. Clinical value of B-type natriuretic peptide levels in umbilical cord blood in

fetal growth restriction and normal pregnancy.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2026; (1): 28-38 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.249

Keywords

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) is associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality and occurs in 5–10% of all pregnancies [1]. FGR is defined as the inability of the fetus to reach its genetically predetermined growth potential in utero. Various conditions affecting the fetus, mother, and placenta predispose pregnancies to FGR. However, in most healthy fetuses, the primary cause is inadequate formation and development of the placenta, which fails to meet the needs of the growing fetus and inhibits its ability to achieve its genetically programmed potential [2].

Long-term follow-up has revealed that children born with FGR are at an increased risk of several metabolic diseases, including obesity and type 2 diabetes. They often experience delayed neuropsychological development, poor school performance, and behavioral problems [3]. Clinically, FGR is categorized into early (<32 weeks of gestation) and late (≥32 weeks) forms, suggesting that different pathophysiological mechanisms may influence the timing of this condition [4].

Newborns with low birth weight exhibit several characteristics related to early neonatal adaptation, such as breathing difficulties, a heightened risk of cardiovascular disease (including high blood pressure, early atherosclerosis, and ischemic disease), metabolic disorders, thermoregulatory issues, increased susceptibility to psychomotor development delays, and a greater likelihood of infection [5, 6]. Specifically, these newborns display echocardiographic signs of cardiac remodeling and dysfunction, characterized by more spherical and less efficient hearts [2]. Cardiovascular changes are more pronounced in cases of early and severe FGR, although they can also occur in mild cases of FGR [7]. Most studies assessing cardiac dysfunction in FGR rely on echocardiography; however, myocardial function can also be evaluated using plasma biomarkers from umbilical cord blood [2].

One such marker is brain B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), which serves as a quantitative indicator of heart failure and reflects both systolic and diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle. BNP levels correlate directly with the severity of heart failure and associated symptoms, making it a valuable tool for diagnosing and monitoring patients with acute and chronic heart failure [8, 9].

BNP, secreted by cardiac myocytes in response to increased ventricular wall tension, enhances diuresis and natriuresis, reduces vascular tone, and plays a crucial role in cardiovascular homeostasis by inhibiting renin and aldosterone secretion [9–12]. Additional research suggests that myocardial ischemia may also contribute to the increased natriuretic peptide levels observed in plasma [11, 13].

Currently, very few studies have assessed BNP levels in umbilical cord blood in newborns during normal pregnancies, compared to those complicated by FGR.

In light of the above, we conducted a study to determine BNP levels in the umbilical cord blood of newborns from both term and preterm births in physiologically normal pregnancies as well as in those complicated by FGR. We aimed to identify correlations between BNP levels and perinatal outcomes in newborns with varying growth and weight parameters.

Materials and methods

A prospective case-control study was conducted from September 1, 2024, to April 1, 2025, at the clinical affiliation of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), S.S. Yudin City Clinical Hospital, Moscow Department of Healthcare. The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of I.M. Sechenov First MSMU (approval number: No. 28-24, November 2025). Pregnant women diagnosed with isolated FGR between 22 and 40 weeks of gestation and admitted to the maternal hospital were invited to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all women who agreed to participate after receiving detailed information.

Study participant recruitment

A total of 69 patients were included in this prospective case-control study. Two groups were formed: the study and control groups. The study group comprised 39 patients diagnosed with FGR according to the criteria outlined in the clinical guidelines "Insufficient Fetal Growth Requiring Medical Care for the Mother" at 22–40 weeks of gestation. The control group included 30 patients with normal fetal weight and height parameters according to the gestational period (22–41 weeks).

We divided the study group into three subgroups: subgroup IA included 10 patients with FGR at full-term gestation of 37–40 weeks and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) fetuses; subgroup IB included 15 patients with early-onset FGR (less than 32 weeks of gestation); and subgroup IC included 14 patients with late-onset FGR at 32–37 weeks of gestation.

The inclusion criteria for the study group comprised singleton spontaneous pregnancies between 22 and 40 weeks of gestation with diagnosed FGR, defined as an estimated fetal weight (EFW) less than the 10th percentile. This was combined with abnormal blood flow or EFW and/or abdominal circumference (AC) values below the 3rd percentile, as well as pregnancies with diagnosed SGA, where fetal size was below the predefined threshold for the corresponding gestational age but with a low risk of perinatal complications (fetus with EFW/AC values in the range from the 3rd to 9th percentile, combined with normal blood flow parameters according to Doppler ultrasound data and the dynamics of EFW and/or AC growth).

The inclusion criteria for the control group involved singleton spontaneous pregnancies between 22 and 41 weeks of gestation with fetal parameters that were normal for the gestational age, defined as EFW from the 10th to 90th percentile.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: multiple pregnancies, chronic heart failure, preexisting type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, cancer, autoimmune diseases, circulatory diseases, fetal anomalies or congenital malformations, drug addiction, and smoking.

Sample size calculation

In this study, we aimed to determine the required sample size to detect significant differences between the FGR and control groups.

To achieve this, we used the following parameters.

- Expected effect size. We hypothesized that cord blood BNP levels would be 2-3 times higher in the FGR group than in the control group.

- Expected outcome frequency. Based on previous studies, we estimated that the expected frequency of the observed outcome (e.g., BNP level) in the control groups would range from 200–6000 pg/mL.

- Statistical significance level (α error). We set the significance level at 0.05, which is the standard value in medical research.

- Statistical Power. We set the study power at 80%, which minimized the likelihood of a Type II error (β-error).

- Statistical Test. Depending on the type of variables and study design, we plan to use tests such as the independent sample Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test.

- Calculation Results. Based on the specified parameters (expected effect size, outcome frequency, significance level, and power), the sample size was calculated using the appropriate statistical formulas or software.

The classic formula for calculating the sample size is as follows:

n = [Z²×p×(1-p)]/[e²+(Z²×p×(1-p)/N), where:

Z is the confidence level (the probability that the obtained results are reliable; for >95% (Z=1.96);

e is the permissible error (maximum deviation from the true value of the parameter).

p is the proportion of the feature (the expected proportion of the element with the desired feature; from 0 to 1, 0.5 if the data are missing);

N is the population size (total number of elements).

n = [1.96²×0.5×0.5]/[0.05²+(1.96²×0.5×0.5/69)];

n = [3.8416×0.25]/[0.0025+(0.9604/69)];

n = 0.9604/0.016419;

n ≈ 58.

We concluded that 58 patients should be included in the study to achieve the required statistical power and obtain reliable results.

Outcomes and their assessment criteria

- Primary outcome of the study: determination and comparison of BNP levels between the study and control groups in the umbilical cord blood of newborns as a potential marker of perinatal complications and fetal health.

- Secondary outcomes of the study included:

- Perinatal outcomes (birth weight, Apgar score at 1 and 5 min after birth, presence of neonatal acidosis, and detection of diastolic myocardial dysfunction according to echocardiography (ECHO-CG) performed in the first hours of the newborn's life)

Perinatal morbidity (presence of respiratory distress syndrome), infectious diseases, heart failure, and autonomic dysfunction syndrome).

Potential confounding factors

- Maternal age may influence pregnancy outcomes and the health of the newborn.

- Presence of chronic diseases, such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or hypertensive disorders.

- Use of assisted reproductive technology (ART).

In our prospective study, the observation period was the first few hours of life. This short period was chosen to assess the BNP level in cord blood, which allowed us to identify possible correlations between the level of this marker and the health of newborns born to mothers with various forms of FGR and in normal pregnancies. Observation in the first hours of life is critical for determining early clinical outcomes and the potential predictive value of BNP levels in the context of FGR.

Study design

Prospective case-control study (Fig. 1).

Cord blood biomarker

Processed blood EDTA was obtained from the umbilical vein, immediately after birth. Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes and stored at 4°C until transfer to the laboratory. BNP levels were measured according to the instructions for the use of commercial kits using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at 450 nm absorbance using a microplate spectrophotometer. Plasma BNP levels were assessed using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays on an Abbott ARCHITECT system (USA). The intra- and inter-day coefficient of variation (CV) values for these kits may vary, but are typically within the following limits: intra-day coefficient of variation (CV) is less than 5%, and inter-day coefficient of variation (CV) is less than 10%.

Sample collection, storage, and analysis were performed according to the test kit manufacturer's instructions.

A total of 69 blood samples were collected from the patients.

Study Protocol

All patients were examined according to The procedure for providing medical care in the field of "Obstetrics and Gynecology (excluding the use of assisted reproductive technologies)" (Order of the Ministry of Health of Russia dated October 20, 2020, No. 1130n), in accordance with the clinical guidelines "Failure to thrive requiring medical care to the mother (FGR)" from 2022.

Gestational age was determined based on the date of the mother's last menstrual period and confirmed by early ultrasound examination. All patients underwent an ultrasound examination with assessment of fetal weight by measuring abdominal circumference, biparietal diameter, head circumference, and femur length using Hadlock biometric curves, as well as standard fetoplacental Doppler ultrasonography using a Siemens ultrasound system. Umbilical cord blood was collected at delivery for subsequent measurement of BNP concentration. Gestational age, birth weight, and Apgar scores in stages 1 and 2 were recorded at delivery. 5 min of life, pH, and lactate level in the blood of a newborn.

The primary endpoints of this study were to assess brain BNP levels in the umbilical cord blood of newborns during normal and FGR pregnancies. The secondary endpoints were to assess perinatal outcomes in relation to brain BNP levels and to identify correlations between BNP levels and perinatal outcome indicators in newborns during the first hours of life.

Thus, this study aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the role of BNP in early neonatal adaptation and its relationship with pregnancy outcomes, which may have important implications for clinical practice.

Statistical analysis

Parametric and nonparametric statistics, SPSS, and Statistica 13.3 (Tibco, USA) were used for the statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was also performed using Microsoft Excel for Windows. The independent variable of interest was the presence of FGR, and the covariates were the presence of hypertensive disorders (preeclampsia (PE), gestational hypertension (GAH), chronic hypertension (CAH)), GDM, and method of conception (ART or natural). Continuous variables are presented as median (Me) and interquartile range [Q1; Q3]. Comparisons between groups were performed using the independent sample Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and were compared using the χ² test and Fisher's exact test. The significance level was set at p≤0.05.

Results

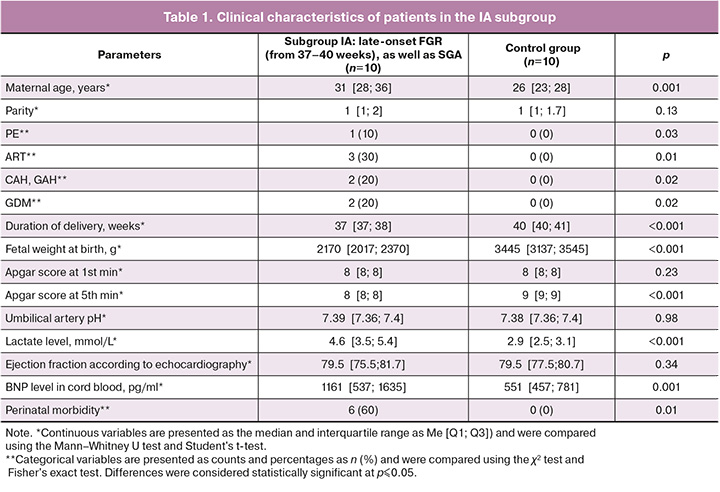

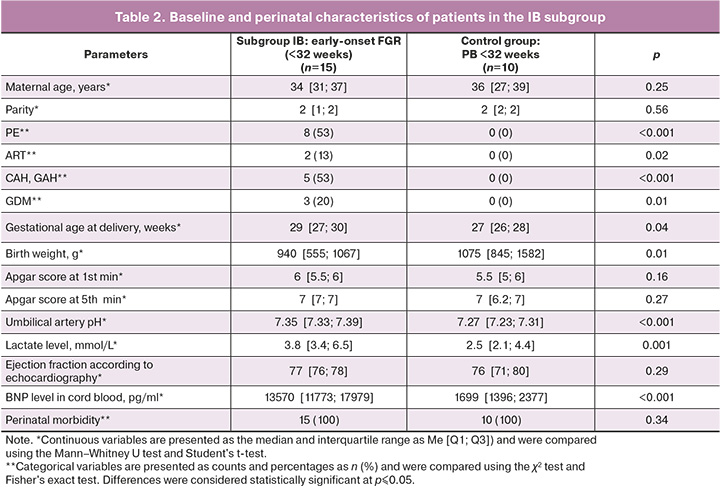

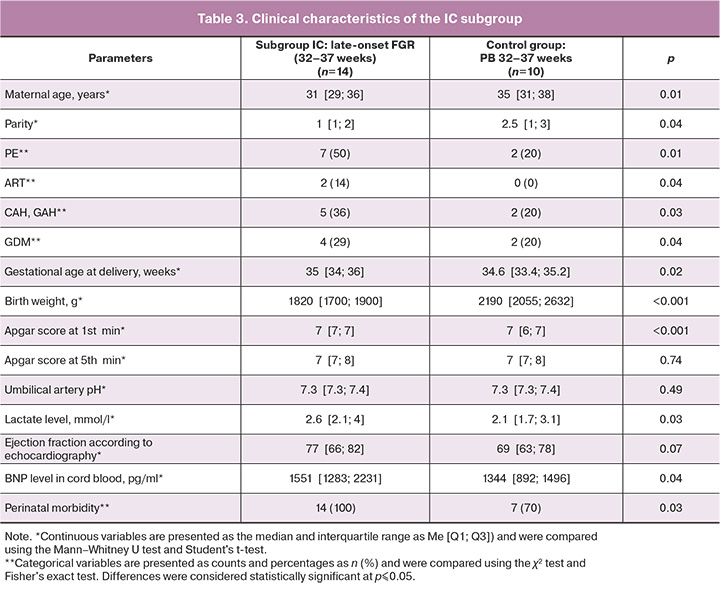

The general clinical characteristics of the study subgroups of patients (IA, IB, and IC) are presented in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

A statistically significant difference was found among all three groups (p<0.05) in terms of gestational age at delivery, birth weight, blood lactate level, and BNP level in umbilical cord blood. Compared with the control group, pregnant women in all FGR subgroups were more likely to have pregnancy complications, such as PE, CAH, GAH, and GDM.

Characteristics of subgroup IA

No statistically significant differences were found between subgroups IA and the corresponding control group in terms of parity, umbilical cord pH, and ejection fraction according to echocardiography data. The median gestational age at delivery in subgroup IA of patients with FGR was 37 [37; 38] weeks, and in the control group, it was 40 [40; 41] weeks; the differences were statistically significant.

The median weight of newborns in the first subgroup was 2170 [2017; 2370] g, and in the control group, it was 3445 [3137; 3545] g, which was 1.5 times higher than that in the subgroup with FGR.

The median lactate level in newborns with FGR was 4.6 [3.5; 5.4] mmol/L, and in newborns without FGR, it was 2.9 [2.5; 3.1] mmol/L; the differences were statistically significant. This indicator was 1.5 times higher in the FGR subgroup than in the control subgroup.

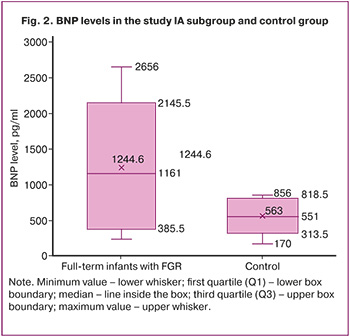

The median concentration of BNP in the umbilical cord in patients with FGR was 1161 [537; 1635] pg/mL, which exceeded the level of this marker by more than 2.1 times compared to the control group (551 [457; 781] pg/ml) (Fig. 2).

The median Apgar score at 1 min in patients with FGR was 8 [8; 8] points, and in the control group, it was also 8 [8; 8] points. The median Apgar score at 5 min in patients with FGR was 8 [8; 8], while in the control subgroup, it was 9 [9; 9] (Table 1).

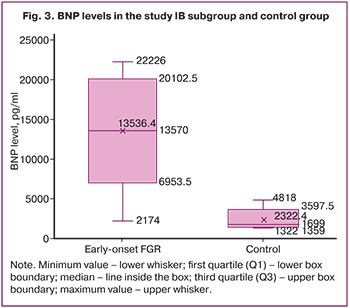

Characteristics of subgroup IB

We compared the clinical characteristics of patients in subgroup IB with those in the control group, which were comparable in terms of delivery time (spontaneous preterm delivery, fetus without FGR). No statistically significant differences were found in maternal age, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min of life, or ejection fraction according to echocardiography data.

The median gestational age in the IB subgroup of patients with FGR was 29 [27; 30] weeks, and in the control group, it was 27 [26; 28] weeks; the differences were statistically significant.

The median weight of newborns in subgroup IB was 940 [555; 1067] g, and in the control group, it was 1075 [845; 1582] g; the differences were statistically significant.

The median lactate level in newborns with FGR was 3.8 [3.4; 6.5] mmol/L, and in newborns in the control group, it was 2.5 [2.1; 4.4] mmol/L; the differences were statistically significant. This indicator was 1.5 times higher in the FGR group than in the control subgroup (Table 2).

The median BNP concentration in the umbilical cord in the subgroup with FGR was 13,570 [11,773; 17,979] pg/mL, which was eight times higher than that in the control group (1, 699 [1, 396; 2, 377] pg/mL) (Fig. 3).

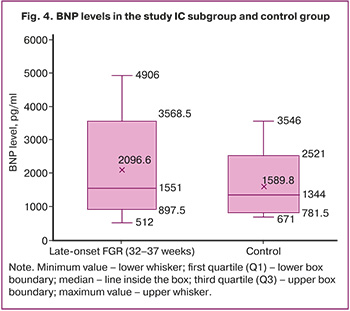

Characteristics of subgroup IC

We compared the clinical characteristics of patients in subgroup IC (late-onset FGR at 32–37 weeks) with a control group comparable in terms of delivery time (spontaneous preterm delivery at 32–37 weeks, fetuses without FGR). No statistically significant differences were found in the IC subgroup in terms of pH in the umbilical artery and ejection fraction according to the ECHO-KG data.

The median weight of newborns in the IC subgroup was 1820 [1700; 1900] g, and in the control group, it was 2190 [2055; 2632] g, which was 1.2 times higher than that in the subgroup with FGR.

The median lactate level in newborns with FGR was 2.6 [2.1; 4] mmol/L, and in newborns without FGR, it was 2.1 [1.7; 3.1] mmol/L; the differences were statistically significant (Table 3).

The median BNP concentration in the umbilical cord in patients with FGR was 1551 [1283; 2231] pg/mL, which exceeded the level of this marker by more than

Newborns with FGR were more likely to be hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit and experience perinatal morbidity than those in the control group. Reasons for intensive care unit admission in newborns included respiratory failure, moderate and severe asphyxia at birth, and heart failure.

Discussion

BNP is the gold standard for diagnosing heart failure and assessing systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in newborns and adults. It is secreted in the ventricles in response to volume overload or hypoxia and increases during the early stages of subclinical diastolic dysfunction as a compensatory mechanism [8, 14, 15]. Myocardial ischemia and related disturbances in cardiac contractile function arise from disruptions in the myocardial energy supply influenced by hypoxia [11, 16, 17]. This progression ultimately leads to heart failure. The study of post-hypoxic myocardial ischemia in newborns is particularly important because early diagnosis and timely treatment during the neonatal period can prevent the long-term adverse effects of existing disorders [18].

Placental transport is crucial for fetal nutrition and metabolism. FGR often results from a reduction in the transfer of nutrients and oxygen from the placenta to the fetus [7]. The concentration of BNP in newborns with FGR is a significant topic in perinatal medicine, as BNP can serve as a marker of cardiac function and the overall condition of the newborn [18].

Research on FGR is essential because it is one of the leading causes of perinatal mortality and morbidity and contributes to the development of chronic diseases in newborns over the long term [20].

Data on BNP concentrations in the context of FGR are scarce. Elevated BNP concentrations have been reported in severe cases of early-onset FGR [21]. A study by Arjamaa O. and Nikinmaa M. indicated that BNP levels may be elevated in newborns with FGR, suggesting potential heart failure or myocardial stress, as these newborns are at a higher risk of cardiovascular complications [17]. Additionally, a study by Perez-Cruz M. et al. found that BNP levels in newborns with FGR may be significantly higher than those in full-term newborns. For instance, one study showed that newborns with FGR exhibited higher BNP levels, which correlated with the severity of growth retardation and the presence of other complications [21].

The primary objective of our study was to investigate BNP levels in umbilical cord blood plasma among newborns in both the control and control groups, in which various forms of FGR were diagnosed. Our findings revealed that serum BNP levels were significantly higher in newborns with FGR than in those in the control group, with the most notable difference observed in the subgroup with early-onset FGR. BNP levels were significantly higher in early-onset FGR than in late-onset FGR. Furthermore, diastolic myocardial dysfunction is more pronounced in early-onset FGR than in late-onset FGR.

Elevated BNP levels detected in the second IB subgroup typically indicate a very high probability of heart failure or other serious cardiac issues, as well as a more severe condition in newborns. However, it is crucial to consider technical factors, such as sample hemolysis, which can distort test results and subsequently affect data interpretation.

BNP levels should be evaluated in the context of the patient's clinical presentation. If symptoms of heart failure (e.g., shortness of breath and edema) are present, elevated BNP levels may confirm the diagnosis. In cases of inconclusive results, it is advisable to retest using a different sample to eliminate the influence of technical factors on the results.

We also identified a correlation between BNP levels, neonatal acidosis, and adverse perinatal outcomes in this study. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring BNP levels during pregnancy, especially in women with risk factors such as FGR. An increase in BNP levels can serve as an indicator of fetal deterioration and a precursor to potential complications, enabling timely interventions to enhance perinatal care. Moreover, the identified associations between BNP and various clinical outcomes may contribute to the development of new strategies for the early diagnosis and prevention of neonatal complications, ultimately improving overall outcomes for both newborns and their mothers.

One potential limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size (only 69 patients divided into three subgroups). Therefore, we plan to explore the feasibility of conducting larger multicenter trials as a direction for future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that BNP may serve as a potential biomarker for perinatal outcomes and neonatal adaptation in newborns, particularly concerning cardiorespiratory aspects in FGR. According to our results, measuring BNP levels in newborns with FGR can predict the clinical course of the early neonatal period in the short term. This test is easily accessible and can be performed in many medical facilities, particularly in locations lacking a third-level neonatal intensive care unit, as it allows for the early identification of the need to transfer a patient to a facility with higher medical care capabilities. This provides guidance for the individualized management of newborns with FGR and the provision of specialized medical care.

In the future, we plan to conduct studies aimed at determining the threshold values of BNP levels that will clearly indicate cardiac dysfunction in newborns. Utilizing umbilical cord blood BNP levels as a routine marker for identifying newborns at risk for cardiac dysfunction holds significant potential but requires further research to confirm its clinical value and to develop appropriate recommendations.

References

- Kucukbas G.N., Kara O., Yüce D., Uygur D. Maternal plasma endocan levels in intrauterine growth restriction. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal Med. 2020; 35(4): 1-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1749591

- Youssef L. , Miranda J., Paules C., Garcia-Otero L., Vellvé K., Kalapotharakos G. et al. Fetal cardiac remodeling and dysfunction is associated with both preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 222(1): 79.e1-e9 https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.025

- Iacovidou N., Briana D., Boutsikou M., Gourgiotis D., Baka S., Vraila V.M. et al. Perinatal changes of circulating N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in normal and intrauterine-growth-restricted pregnancies. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2007; 26(4): 463-71. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10641950701548414

- Gordijn S.J., Beune I.M., Thilaganathan B., Papageorghiou A., Baschat A.A., Baker P.N. et al. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure. Ultras. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 48(3): 333-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.15884

- Salas G.L., Jozefkowicz M., Goldsmit G.S. B-type natriuretic peptide: usefulness in the management of criticallyill neonates. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2017; 115(5): 483-9. [Article in English, Spanish]. https://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2017.eng.483

- Леонова А.А., Кан Н.Е., Тютюнник В.Л., Серебрякова А.П., Хачатурян А.А., Пекарева Н.А. Неонатальные осложнения и особенности постнатального развития детей при задержке роста плода. Акушерство и гинекология. 2025; 7: 67-75. [Leonova A.A., Kan N.E., Tyutyunnik V.L., Serebryakova A.P., Khachaturyan A.A., Pekareva N.A. Neonatal complications and characteristics of postnatal development of infants with fetal growth restriction. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2025; (7): 67-75 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.134

- Eroğlu H., Erdöl M.A., Tonyalı N.V., Örgül G., Biriken D., Yücel A. et al. Maternal serum and umbilical cord brain natriuretic peptide levels in fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 2022; 41(5): 722-30. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15513815.2021.1955057

- Esbrand F.D., Zafar S., Panthangi V., Cyril Kurupp A.R., Raju A., Luthra G. et al. Utility of N-terminal (NT)-brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP) in the diagnosis and prognosis of pregnancy associated cardiovascular conditions: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022; 14(12): e32848. https://dx.doi.org/10.7759/cureus.32848

- Тимохина Е.В., Игнатко И.В., Григорьян И.С., Сарахова Д.Х., Федюнина И.А., Богомазова И.М., Песегова С.В., Сеурко К.И., Мэлэк М., Черкашина А.В. Значение мозгового натрийуретического пептида в оценке состояния плода и прогнозировании перинатальных исходов у беременных с преэклампсией. Архив акушерства и гинекологии имени В.Ф. Снегирева. 2025; 12(2): 205-15. [Timokhina E.V., Ignatko I.V., Grigoryan I.S., Sarakhova D.K., Fedyunina I.A., Bogomazova I.M., Pesegova S.V., Seurko K.I., Melek M., Cherkashina A.V. The role of brain natriuretic peptide in assessing fetal status and predicting perinatal outcomes in pregnant women with pre-eclampsia. V.F. Snegirev Archives of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; 12(2): 205-15 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17816/aog641833

- Giannubilo S.R., Pasculli A. , Tidu E., Biagini A. , Boscarato V. , Ciavattini A. Relationship between maternal hemodynamics and plasma natriuretic peptide concentrations during pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. J. Perinatol. 2017; 37(5): 484-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.264

- Suttner S., Boldt J. Natriuretic peptide system: physiology and clinical utility. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 2004; 10(5): 336-41. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ccx.0000135513.26376.4f

- Kale A., Kale E., Yalinkaya A., Akdeniz N., Canoruç N. The comparison of amino-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide levels in preeclampsia and normotensive pregnancy. J. Perinat Med. 2005; 33(2): 121-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/JPM.2005.023

- Тимохина Е.В., Игнатко И.В., Григорьян И.С., Федюнина И.А., Богомазова И.М. Гемодинамическая дезадаптация беременной как ранний маркер развития преэклампсии. Акушерство, гинекология и зепродукция. 2023; 17(4): 455-61. [Timokhina E.V., Ignatko I.V., Grigoryan I.S., Fedyunina I.A., Bogomazova I.M. Hemodynamic maladaptation of a pregnant woman as an early marker of preeclampsia. Obstetrics, gynecology and reproduction. 2023; 17(4): 455-61 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2023.397

- Shen H., He Q., Shao X., Lin Y.H., Wu D., Ma K. et al. Predictive value of NT-proBNP and hs-TnT for outcomes after pediatric congenital cardiac surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2024; 110(6): 3365-72. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000001311

- Maalouf R., Bailey S. A review on B-type natriuretic peptide monitoring: assays and biosensors. Heart Fail. Rev. 2016; 21(5): 567-78. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10741-016-9544-9

- Bae J.Y., Seong W.J. Umbilical arterial N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels in preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth and fetal distress. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 43(3): 393-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.12891/ceog3103.2016

- Arjamaa O., Nikinmaa M. Hypoxia regulates the natriuretic peptide system. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2011; 3(3): 191-201.

- Crispi F., Crovetto F., Gratacos E. Intrauterine growth restriction and later cardiovascular function. Early Hum. Dev. 2018; 126: 23-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.08.013

- Масленникова И.Н., Бокерия Е.Л., Казанцева И.А., Иванец Т.Ю., Дегтярев Д.Н. Диагностическое значение определения уровня натрийуретического пептида при сердечной недостаточности у новорожденных детей. Российский вестник перинатологии и педиатрии. 2019; 64(3): 51-9. [Maslennikova I.N., Bokerija E.L., Kazantseva I.A., Ivanets T.Yu., Degtyarev D.N. Value of the natriuretic peptide level in diagnostics of newborns with heart failure. Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics. 2019; 64(3): 51-9 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.21508/1027-4065-2019-64-3-51-59

- Hogeveen M., Blom H.J., den Heijer M. Maternal homocysteine and small-for-gestationalage offspring: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012; 95(1): 130-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.016212

- Perez-Cruz M., Crispi F., Fernández M.T., Parra J.A., Valls A., Gomez Roig M.D. et al. Cord blood biomarkers of cardiac dysfunction and damage in term growth-restricted fetuses classified by severity criteria. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2018; 44(4): 271-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000484315

Received 09.09.2025

Accepted 28.10.2025

About the Authors

Kseniya I. Seurko, PhD student at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119048, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8 build. 2; Obstetrician-Gynecologist, S.S. Yudin City Clinical Hospital, 115446, Russia, Moscow, Kolomensky Passage, 4 build. 2, +7(915)178-42-13, kseurko@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3287-9254Elena V. Timokhina, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119048, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8 build. 2, +7(916)607-45-34, timokhina_e_v@staff.sechenov.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6628-0023

Irina V. Ignatko, Dr. Med. Sci., Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119048, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8 build. 2, +7(910)461-73-02, ignatko_i_v@staff.sechenov.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9945-3848

Dzhamilya Kh. Sarakhova, PhD, Deputy Chief Physician for Obstetric and Gynecological Care, S.S. Yudin City Clinical Hospital, 115446, Russia, Moscow, Kolomensky Passage, 4 build. 2, +7(905)708-84-66, SarakhovaDK@zdrav.mos.ru, https://orcid.org/0009-0008-0531-0899

Vladimir A. Titov, Head of the Department of Resuscitation and Intensive Care for Newborns and Premature Infants S.S. Yudin City Clinical Hospital, 115446, Russia, Moscow, Kolomensky Passage, 4 build. 2, +7(926)223-97-02, titoww@gmail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2105-9709

Kirill I. Seurko, PhD, Teaching Assistant at the Department of Hospital Surgery of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119048, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8 build. 2, +7(916)628-92-13, kirill.seurko@yandex.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5150-8793

Alexandra V. Saykina, student at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119048, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8 build. 2, +7(926)852-06-27, a_saykina@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-5743-566X

Madina A. Kardanova, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology of the Institute of Clinical Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119048, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8 build., +7(926)383-84-80,

kardanova_m_a@staff.sechenov.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4315-0717

Corresponding author: Kseniya I. Seurko, kseurko@yandex.ru