Sociodemographic factors influencing the health of pregnant women: changes in the Arctic countries over the past decades

Objective. To study the past decades’ changes in the sociodemographic factors that determine the health of reproductive-aged women in the Arctic countries.Treskina N.A., Postoev V.A., Usynina A.A., Grjibovski A.M., Odland J.Ø.

Materials and methods. The paper presents a systematic review of studies that evaluate trends in the prevalence of sociodemographic factors that determine the health of reproductive-aged women in the Arctic countries over the past decades. The 1970–2019 publications were sought by the results of cross-sectional, cohort studies of the trend in the MEDLINE and e-LIBRARY databases in Russian and English. The review also includes reports from the Federal Service for State Statistics of the Russian Federation (RF), the statistical centers of Norway, Finland, and Denmark. Twenty-three studies met the selection criteria.

Results. The investigators found pan-Artic trends: an increase in the mean age of primiparas, decreases in the teenage birth rate and in the proportion of married mothers, increases in the proportion of common-law mothers and in that of mothers who did highly skilled labor. By 2018, the mean age of mothers in the RF increased to 28.7 years. The mean age of primiparas in Finland in 2018 was 29.3 years; and that in Norway and Denmark in 2019 was 29.8 and 29.5 years, respectively. The teenage birth rate in the RF fell to 20.7 births per 1,000 girls aged 15-19, but this figure was much higher than that in Canada (8.4), Norway (5.1), Sweden (5.1), Finland (5.8), and Denmark (4.1). The proportion of married puerperas in the USSR in 1970 was 89.4% and that decreased to 78.2% (the RF data) in 2018. In Norway, that of married primiparas almost halved over this period. There was an increase in the proportion of primiparas with upper secondary and higher education.

Conclusion. Over the past decades, considerable changes have been identified in the portrait of a pregnant woman, namely: there is an increase in the mean age of primiparas, decreases in the teenage birth rate and in the proportion of married mothers, and increases in the proportion of common-law mothers and in that of mothers who have upper secondary and higher education, and, consequently, are involved in highly skilled labor.

Keywords

The key components of the demographic policy of the subarctic states are to strengthen the reproductive health of the population, reduce maternal and infant mortality, and increase the birth rate. The above-mentioned demographic indicators are determined mainly by the population health level that, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), for several indicators in Russia remains lower than in European countries [1]. Thus, life expectancy at birth for women in Russia in 2018 was 77.82 years [2], while in Norway in 2016, that was 84.17 years, and 82.79 and 84.09 in Denmark and Sweden, respectively [3].

Adverse pregnancy outcomes such as premature birth, low birth weight (less than 2500 g), and very low birth weight (less than 1500 g) have serious health consequences in infancy and childhood, and adult life, increasing the burden of disease in the adult population. In Denmark in 2008, very low birth weight and low birth weight infants accounted for 0.9% and 4.4% of all live births, respectively. Similar results were observed in Finland (0.8% and 3.4%), Sweden (0.7% and 3.5%) and Norway (0.9% and 3.9%). The frequency of preterm birth in 2008 in these countries was: in Denmark 7%, in Finland 5.6%, in Sweden and Norway 6.3 and 7%, respectively [4].

In Russia, before the transition to the new medical criteria of birth registration, the frequency of premature births (28–37 weeks of gestation) was 3.6% in 2008 and 3.9% in 2011. In 2012, Russia followed the WHO recommendation to register live births with a bodyweight of 500 g or more and a gestation age of 22 weeks or more; thus, the proportion of premature births was 4.3%, remaining slightly higher (4.4%) in 2018 [ 5].

The health of the future mother and pregnancy outcomes depend on socio-demographic and behavioral factors. Their change during the recent decades has contributed to the change of indicators in the reproductive health of women and the health of children, including infants.

This study aimed to assess the changes in socio-demographic factors that determine the health of reproductive-aged women in the subarctic states over the past decades. To achieve this goal, a systematic review of the satisfying selection criteria studies was performed.

Materials and methods

The selection of studies was carried out following the PRISMA criteria (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyzes) [6]. The systematic review included studies from 1970–2019, satisfying the following criteria: cross-sectional, trend studies, cohort studies, including those based on population registries and birth registries. The search was carried out in the MEDLINE and e-LIBRARY databases in Russian and English. In addition, the review included reports from the Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat) on the demographic situation and reproductive health of the population [7, 8], as well as data from the statistical services of Norway, Finland, and Denmark.

The keywords for searching of articles in Russian and in English were «maternal age», «maternal education», «marital status», «maternal occupation (presence or absence of work/study)».

The subarctic states include eight countries: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States (USA). The systematic review included publications on results of original research carried out in the northwestern part of Russia, Finland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, the USA (Alaska), and the northern part of Canada. Based on the Decree of the President of Russia from May 2, 2014, No. 296, only eight constituent entities of Russia are included in the Arctic zone of Russia [9]. The results of studies carried out in some of them (Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions, and the Komi Republic) are presented in the article.

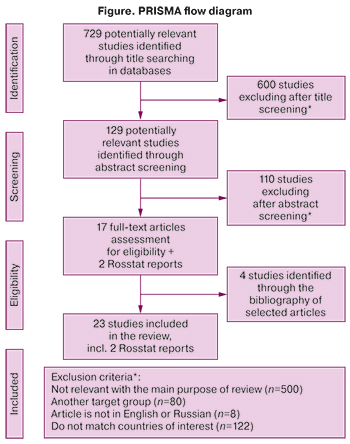

The preliminary selection of the articles was made based on the title of the publications; subsequently, the content of the abstracts and the full text of the articles were taken into account. The bibliography of selected articles was also examined. The quality of articles was assessed using the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) criteria [10]. The scheme of selection of studies for review is shown in the figure.

The preliminary selection of the articles was made based on the title of the publications; subsequently, the content of the abstracts and the full text of the articles were taken into account. The bibliography of selected articles was also examined. The quality of articles was assessed using the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) criteria [10]. The scheme of selection of studies for review is shown in the figure.

At the first stage, 729 articles were selected, but only 23 satisfied all inclusion criteria. Nineteen publications were in English, four (two of which were Rosstat publications) were in Russian. All 23 publications are dated 1988–2019. Maternal age was studied in 16 articles, education, and marital status, in 8 and 11 publications, respectively. Employment was the subject of discussion in five studies selected for the review. Ten studies provide an analysis of the prevalence of several socio-demographic factors.

Results

Maternal age

Both very young and women 35 years of age and older are associated with an increased risk of some adverse outcomes for mother and child [11–18]. In recent decades, in many countries, including Russia (until 1991 - the USSR), there has been a stable trend towards increasing the proportion of mothers of late reproductive age [11–14, 19]. In Russia, the number of births per 1000 girls aged 15–19 has decreased by almost 2.5 times (from 51.8 to 20.7) compared to the periods 1990–1995 and 2015–2020. At the same time, the level of adolescent fertility in 2015–2020 in Russia, despite a significant decrease over the past thirty years, far exceeded this indicator in Canada (8.4 births per 1000 girls aged 15–19), Norway, and Sweden (5.1 births per 1000 girls), Finland (5.8) and Denmark (4,1) [20].

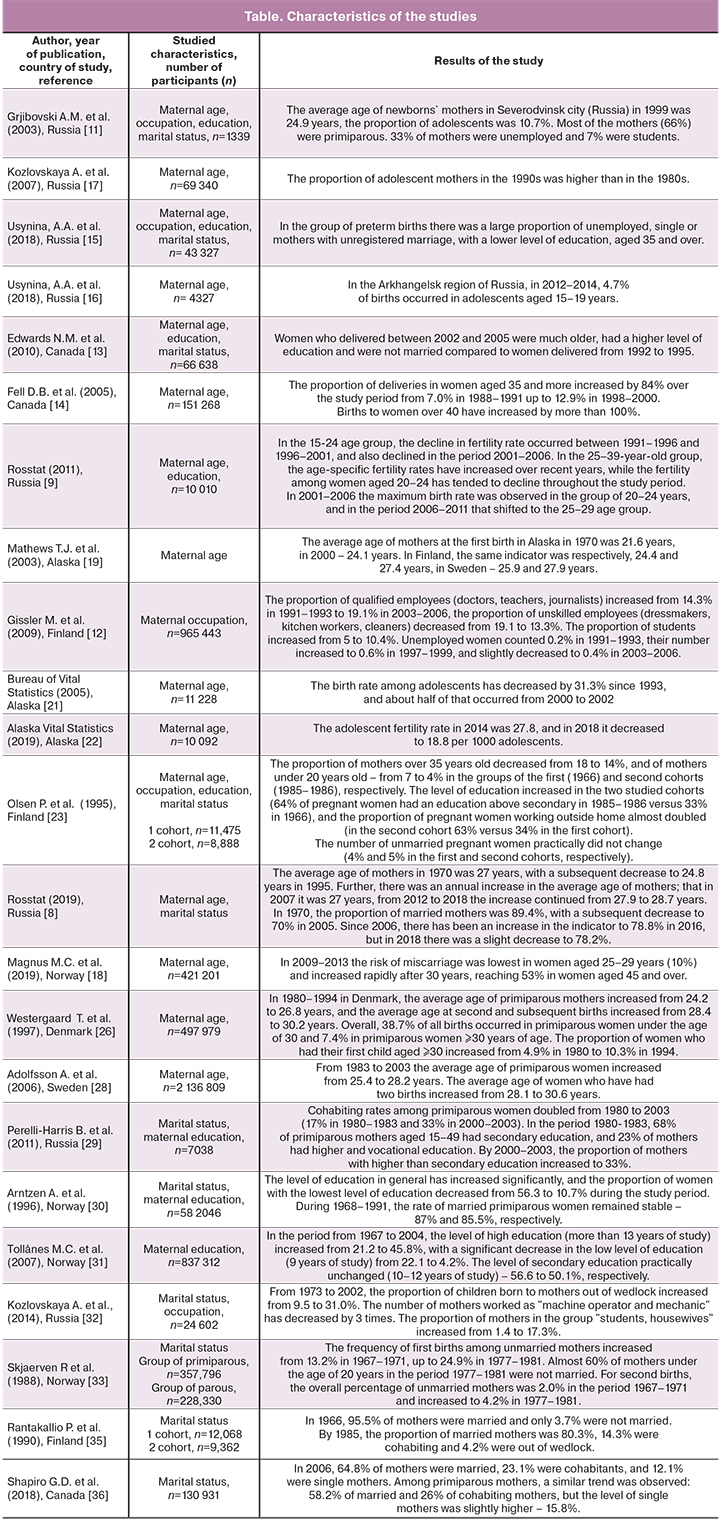

The characteristics of the studies used for the review are presented in the table.

A study in Syktyvkar and Vorkuta (Komi Republic, Russia), which included 69,000 observations, revealed that most mothers in 1980–1999 were 20–29 years old. The proportion of adolescent mothers in Syktyvkar and Vorkuta in 1980–1984 was 8.9 and 9.6%, and in 1995–99 increased to 15 and 17.3% [17].

The age of mothers of 1339 newborns in Severodvinsk (Russia) in 1999 averaged 24.9 years. The proportion of adolescents in the studied cohort was 10.7%, and the proportion of mothers aged 20–24 was 44%. The majority of mothers (66%) were primiparous [11].

A study based on data from the regional birth registry in the Arkhangelsk region in 2012–2014 showed that 4.7% of births occurred in adolescents aged 15–19 years [16].

According to Rosstat, the average age of mothers in Russia in 1970 was 27 years, with a subsequent decrease to 24.8 years in 1995. Further, there was an annual increase in the average age of mothers; in 2007, it was 27 years, from 2012 to 2018, the growth continued from 27.9 to 28.7 years [7].

In the 15–24 age group, the decline in the birth rate in Russia occurred between 1991–1996 and 1996–2001 and continued in the period 2001–2006. In the 25–39-year-old group, the age-specific fertility rates have increased over recent years, while the fertility among women aged 20–24 has tended to decline throughout the study period. In 2001–2006, the maximum birth rate was observed in the group of 20–24 years, and in the period 2006–2011, that shifted to the 25–29 years age group [8], remaining the same in 2012–2018 [7].

The mean age of primiparous mothers in Alaska in 1970 was 21.6 years, in 2000 – 24.1 years [19]. The adolescent fertility rate decreased by 31.3% between 1993 and 2002; in 1993, this indicator was 60.7 births, and in 2002 – 41.7 births per 1000 adolescents [21]. The adolescent fertility rate in 2014 and 2018 decreased from 27.8 to 18.8 per 1000 adolescents. By 2018, the mean age of mothers in Alaska had increased to 28.6 years [22].

In Finland, the proportion of mothers over 35 years decreased from 18 to 14%, and mothers under 20 years old – from 7 to 4% in the period from 1966 to 1985 [23]. The mean age of primiparous mothers in 1970 and 2000 was 24.4 and 27.4 years in Finland, respectively, in Sweden – 25.9 and 27.9 years [19]. There was the mean maternal age variability during the studied period. In 1991–1993 in Finnish women, maternal age was 29.3 years, which subsequently decreased [19], but already in 2003–2006 reached the age of 30 [12]. In 2010, the age of primiparous in Finland was 28.2 years, and in 2018 it was 29.3 years, with the mean age of all mothers 31 years. The percentage of mothers over 35 years old in 1987 was 13.3%, and by 2018 it reached 23.7%. The proportion of mothers under 20 years of age gradually decreased from 3.2% in 1987 to 2.3% in 2010, and in 2018 it was 1.3% [24].

In Norway, the mean age of primiparous has increased over the past decades, amounting to 23.2 years in 1970, 24.3 in 1980, and 28.1 and 29.8 years in 2010 and 2019, respectively. The number of births per 1000 girls aged 15–19 decreased by 87.3% (from 18.2 in 1986 to 2.3 in 2019) [25].

In 1980–1994 in Denmark, the mean age of primiparous women has increased from 24.2 to 26.8 years. The mean age at second and subsequent births increased from 28.4 to 30.2 years. In general, 38.7% of all births occurred in primiparous women under 30 and 7.4% in primiparous women aged 30 and over. The proportion of women who had their first child at the age of 30 or more increased from 4.9% in 1980 to 10.3% in 1994 [26]. In 2000, the mean age of primiparous was 28.1 years, in 2010 and 2019, respectively, 29 and 29.5 years [27].

In Sweden, from 1983 to 2003, the mean age of primiparous women increased from 25.4 to 28.2 years. The mean age of women who have had two births increased from 28.1 to 30.6 years during this period [28].

In Canada, 12.6% of women who gave birth to children between 2002 and 2005 were over 34 years old. In 1992–1995 the proportion of mothers under 20 years was 10.1% [13]. Surprisingly, 30% of all live births in 1997 were among women 30–34 years old, 58% more than in 1981. The proportion of mothers over 35 years old increased by 84% during the study period (from 7.0 to 12, 9%, respectively, in 1988–1991 and 1998–2000). At the same time, the proportion of women over 40 years of age increased by more than 100% [14].

Maternal education

In Russia in 1999, 21% of mothers had a higher education, and only 4% had a secondary education [11]. According to a study conducted by Rosstat in 2010, maternal age at childbirth and the level of education are interrelated. The highest birth rate at the age of 25–29 was observed among women with higher education, while among women with a lower level of education, the highest birth rate was observed at the age of 20–24. For women over 30, there were practically no significant differences in fertility rates in terms of education. The average age of primiparous mothers was higher among women with higher education (25.1 years) compared to women with less than secondary education (20.9 years) [8].

According to the results of a study based on data from the regional birth registry of the Arkhangelsk region in 2012–2014, the proportion of women with vocational education was 43.9% [15]. During 1980–1983, 68% of primiparous mothers aged 15–49 years in Russia had secondary education, and 23% of mothers had higher and vocational education. By 2000–2003, the proportion of mothers with higher than secondary education rose to 33%. In addition, during the study period from 1980 to 2003, women with less than secondary education had the highest fertility rates as cohabiting or single mothers [29].

In Finland in 1966, mothers with secondary and lower education accounted for 65% of the study group. By 1985–1986 the proportion of mothers with this level of education decreased to 23% and increased to 64% the proportion of women with vocational education [23]. In 2008, 15% of pregnant women had only primary education, 40.1% – secondary, and 44.9% – above secondary [4].

In Norway during 1968–1991, the level of education has increased significantly (26.2% of primiparous received 12 years of education and more in 1989–1991 versus 9% in 1968–1971). The proportion of women with the lowest level of education decreased from 56.3 to 10.7% over the study period [30]. In the period from 1967 to 2004, the level of high education (more than 13 years of study) increased from 21.2 to 45.8%, with a significant decrease in the low level of education (9 years of study) from 22.1 to 4.2% and the secondary level of education (10–12 years of study) did not change – 56.6 and 50.1%, respectively [31].

In Canada in 1992–1995, the proportion of mothers with incomplete secondary education was 25.3% against 13.6% in 2002–2005. Over this period, the proportion of mothers with higher than secondary education increased from 48.8 to 69% [13].

Marital status

The proportion of women in childbirth in the USSR and Russia with a registered marriage varied. In 1970, that amounted to 89.4% with a subsequent decrease to 70% by 2005. Since 2006, there was an increase in this indicator to 78.8% in 2016, but in 2018, a decrease was again noted to 78.2% [7]. In Russia in 1999, 35% of mothers were unmarried [11]. The frequency of cohabitation in Russia among primiparous women doubled from 1980 to 2003 (17% in 1980–1983 and 33% in 2000–2003) [28]. In Monchegorsk (Murmansk region) from 1973 to 2002, the proportion of children born to mothers out of wedlock increased from 9.5 to 31% [32].

In Norway in 1968–1991, the level of married primiparous women remained practically stable, amounting to 87–85.5% [30]. The proportion of unmarried primiparous mothers increased from 13.2% in 1967–1977 to 24.9% in 1977–1981. Almost 60% of mothers under the age of 20 in 1977–1981 were not married. In second births, the proportion of unmarried mothers was 2% in 1967–1971 and increased to 4.2% in 1977–1981 [33]. Between 2002 and 2019, most primiparous women did not have an official marriage; thus, in 2002, only 35.4% of mothers were married, 45.6% of children were born in cohabitation, and 19% were single mothers. In 2019, these indicators were 31.4, 55, and 13.6%, respectively. At the birth of a second child, the proportion of married and unregistered primiparous mothers becomes approximately the same (43 and 48%, respectively). Only at the birth of third and subsequent children does the proportion of married mothers prevail [34]. From 2002 to 2019, there was a decrease in the proportion of married women from 49.3 to 41% and an increase in the proportion of mothers outside marriage (from 38.5 to 48%) [34].

In Finland in 1966, 95.5% of mothers were married. By 1985, the proportion of married mothers had dropped to 80.3%. Women outside marriage accounted for 14.3%, and 4.2% were single [35]. In 1987, 80% of mothers were married, and another 12% were not married. In 2010, these indicators were 57.8 and 32.5%, in 2018 – 54.1 and 33.2%, respectively [24]. The proportion of single mothers increased from 6% to 13.2% in 1991–1993 and 2000–2002. However, in 2003–2006 there was a decrease in the proportion of single mothers to 9.9% [12].

In Canada in 1992–1995, the proportion of married women was 73.7% against 56.6% in 2002–2005. [13]. In 2006, 64.8% of mothers were married, 23.1% were not married, and 12.1% were single. Among primiparous mothers, a similar trend was observed: 58.2% of women were married, 26% were outside marriage, but the level of single mothers was slightly higher [15.8%] [36].

Maternal occupation (presence or absence of work/study)

In a study conducted in Russia in 1999, 33% of mothers were unemployed, and 7% were students [11]. From 1973 to 2002 in Monchegorsk (Murmansk region), the proportion of mothers employed as "machine operator and mechanic" decreased by three times. At the same time, the proportion of student mothers and housewives increased from 1.4 to 17.3% [32]. In the Arkhangelsk region in 2012–2014, 22% of mothers were unemployed [15].

In Finland in 1985–1986, the proportion of women working full-time outside of the home increased to 63%, while in 1966, 60% of mothers were housewives [23]. The proportion of doctors, teachers, journalists risen from 14.3% in 1991–1993 to 19.1% in 2003–2006, the proportion of mothers employed in factories and mothers performing unskilled labor (dressmakers, kitchen workers, cleaners) decreased from 19.1 to 13.3%. The proportion of students increased from 5 to 10.4%. Unemployed women at the time of birth in 1991–1993 counted 0.2%, rose to 0.6% in 1997–1999, and slightly decreased to 0.4% in 2003–2006 [12].

Discussion

Studying socio-demographic factors and monitoring their changes over time is very important for practical medicine and individual assessment of the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Also, that is important for public health to determine priorities in developing preventive programs and assess the potential possibilities in reducing the perinatal and infant mortality rates. Earlier, the relationship of the studied factors with an increased risk of preterm birth, stillbirth, and infant mortality was demonstrated in Russian and foreign studies.

Our systematic review demonstrated not only intercountry variability in the socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women but also a significant change of these factors in the temporal aspect. Moreover, many of them are associated, and these associations were general for most of the studied countries and territories. Thus, an increase in the average age of primiparous mothers has led to the rise in the proportion of women with higher education, has changed the structure of women's employment. Namely, the proportion of mothers performing highly skilled labor has increased. In addition, there has been a shift from registered marriage towards "cohabitation." At the same time, several characteristics differed significantly between countries. For example, the level of teenage pregnancy in Russia was several times higher than similar indicators in North America and Northern Europe.

It is considered that socio-demographic characteristics are closely related to the economic processes of the country. That is why studies based on birth registries [16, 17, 32] are particularly interesting since they allow the collection of comparable data using a similar technique over a long time. The only registry in Russia covering a relatively long observation period (1973–2012) is the Kola (Monchegorsk) birth registry. Based on this data, for example, we could talk about an increase in the proportion of children born out of an official marriage by unemployed mothers during socio-economic transformations in Russia in the 1990s. [32].

This review is the first such study in Russian carried out in accordance with the PRISMA requirements. Possible limitations of the study are the inclusion of publications and official statistics in Russian and English. At the same time, some of the statistical information in the Scandinavian countries is presented in the official language, which could make the presented statistical data for these countries incomplete. Rigorous selection of publications for this review allowed, on the one hand, to achieve comparability of results due to limitations in design and the study population. On the other hand, it may have led to the exclusion of publications in Russian with unspecified research methodology.

Conclusion

Over the past decades, significant changes have been revealed in the "portrait" of a pregnant woman, namely: an increase in the average age of primiparous mothers, a decrease in the adolescent fertility rate, a reduction in the proportion of mothers with a registered marriage and an increase in the proportion of cohabitation, an increase in the proportion of mothers with higher and vocational education, and, therefore, engaged in highly skilled labor.

References

- WHO. World Health Statistics 2018: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272596/9789241565585-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Женщины и мужчины России 2018. Статистический сборник. М.: Росстат; 2018. [Rosstat. Women and men of Russia, 2018. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://www.gks.ru/storage/mediabank/wo-man18.pdf

- Ho J.Y., Hendi A.S. Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries: retrospective observational study. BMJ. 2018; 362: k2562. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2562.

- Europeristat Report. 2008. Available at: https://www.europeristat.com/our-publications/european- perinatal-health-report.html

- Росстат. Состояние здоровья беременных, рожениц, родильниц и новорожденных 2019. [Rosstat. The health status of pregnant women, women in labor, postpartum women and newborns, 2019. (in Russian)]. Available at: www.gks.ru

- Унгуряну Т.Н., Жамалиева Л.М., Гржибовский А.М. Краткие рекомендации по подготовке систематических обзоров к публикации. West Kazakhstan Medical Journal. 2019; 61(1): 26-36. [Unguryanu T.N., Zhamaliyeva K.M., Grjibovski A.M. Brief recommendations on how to write and publish systematic reviews. West Kazakhstan Medical Journal. 2019; 61(1): 26-36. (in Russian)].

- Демографический ежегодник России 2019. Статистический сборник. M.: Росстат; 2019. [Rosstat. Demographic Yearbook of Russia, 2019. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://www.gks.ru/storage/mediabank/Dem_ejegod-2019.pdf

- Репродуктивное здоровье населения России 2011. Итоговый отчет. М.: Росстат; май 2013. [Rosstat. Reproductive health of the population of Russia, 2011. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://www.gks.ru/storage/mediabank/zdravo-2011.pdf

- Указ Президента РФ от 2 мая 2014 г. № 296 «О сухопутных территориях Арктической зоны Российской Федерации». [Decree of the President of the Russian Federation from May 2, 2014 No 296 “The land territories of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation”. (in Russian)]. Available at: https://www.garant.ru/products/ipo/prime/doc/70547984/#review

- The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Available at: https://www.equator- network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/

- Grjibovski A.M., Bygren L., Svartbo B., Magnus P. Social variations in fetal growth in a Russian setting: an analysis of medical records. Ann. Epidemiol. 2003; 13(9): 599-605. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00052-8.

- Gissler M., Rahkonen O., Arntzen A., Cnattingius S., Andersen A.M., Hemminki E. Trends in socioeconomic differences in Finnish perinatal health 1991–2006. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 2009; 63(6): 420-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.079921.

- Edwards N.M., Audas R.P. Trends of abnormal birthweight among full-term infants in Newfoundland and Labrador. Can. J. Public Health. 2010; 101(2): 138-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03404359.

- Fell D.B., Joseph K.S., Dodds L., Allen A.C., Jan Gaard K., Van den Hof M. Changes in maternal characteristics in Nova Scotia, Canada from 1988 to 2001. Can. J. Public Health. 2005; 96(3): 234-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03403698.

- Усынина А.А., Постоев В.А., Одланд И.О., Меньшикова Л.И., Пылаева Ж.А., Пастбина И.М., Гржибовский А.М. Влияние медико-социальных характеристик и стиля жизни матерей на риск преждевременных родов в арктическом регионе Российской Федерации. Проблемы социальной гигиены, здравоохранения и истории медицины. 2018; 26(5): 302-6. [Usynina A.A., Postoev V.A., Odland I.O., Menshikova L.I., Pylaeva Z.A., Pastbina I.M., Grzhibovskii A.M. The Effect of Medical Social Characteristics and Style of Life of Mothers on Premature Delivery Risks in the Arctic Region of the Russian Federation. Problems of social hygiene, health care and the history of medicine. 2018; 26(5): 302-6. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.32687/0869-866X-2018-26-5-302-306.

- Usynina A.A, Postoev V., Odland J.Ø., Grjibovski A.M. Adverse pregnancy outcomes among adolescents in Northwest Russia: A population registry-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018; 15: 261. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020261.

- Kozlovskaya A., Bojko E., Odland J.Ø., Grjibovski A.M. Secular trends in pregnancy outcomes in 1980–1999 in the Komi Republic, Russia. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2007; 66(5): 437-48. https://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v66i5.18315.

- Magnus M.C., Wilcox A.J., Morken N.-H., Weinberg C.R., Håberg S.E. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register-based study. BMJ. 2019: l869. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l869.

- Mathews T.J., Hamilton B.E. Mean age of mother, 1970–2000. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2003; 51(1): 1-13.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population prospects highlights. 2019 Revision. Available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf

- Department of Health and Social Services of Alaska, Division of Public Health. Teen births in Alaska, 1993 to 2002. Alaska Vital Signs. 2005; 1(2): 1-4. Available at: https://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/VitalStats/Documents/PDFs/vitalsigns/Teen_Births_20. 02.pdf

- Department of Health and Social Services of Alaska, Division of Public Health. Alaska vital statistics 2018. Annual report. 2019.

- Olsen P., Laara E., Rantakallio P., Jarvelin M.R., Sarpola A., Hartikainen A.L. Epidemiology of preterm delivery in two birth cohorts with an interval of 20 years. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1995; 142(11): 1184-93. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117577.

- Finnish institute for health and well-being. Perinatal statistics – women in labor, childbirth and newborns. 2018. Available at: https://thl.fi/documents/10531/0/Tr49_19_liitetaulukot.pdf/712d65c7-3e78-d811-6aab-bee80ccaa12f?t=1576739595794

- Statistics Norway. Mean age of parent at first child's birth, by contents and year. 2019. Available at: https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank/table/07872/tableViewLayout1/

- Westergaard T., Wohlfahrt J., Aaby P., Melbye M. Population based study of rates of multiple pregnancies in Denmark 1980–94. BMJ. 1997; 314: 775-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7083.775.

- Statistics Denmark. Average age of women given birth and new fathers by age and time. 2019. Available at: https://www.statbank.dk/10017

- Adolfsson A., Larsson P.-G. Cumulative incidence of previous spontaneous abortion in Sweden in 1983–2003: a register study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2006; 85(6): 741-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016340600627022.

- Perelli-Harris B., Gerber T.P. Nonmarital childbearing in Russia: second demographic transition or pattern of disadvantage? Demography. 2011; 48(1): 317-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13524-010-0001-4.

- Arntzen A., Moum T., Magnus P., Bakketeig L.S. The Association between maternal education and postneonatal mortality. Trends in Norway, 1968–1991. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1996; 25(3): 578-84. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/25.3.578.

- Tollånes M.C., Thompson J.M.D., Daltveit A.K., Irgens L.M. Cesarean section and maternal education; secular trends in Norway, 1967–2004. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007; 86(7): 840-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016340701417422.

- Козловская А.В., Одланд Ю.О., Гржибовский А.М. Влияние профессиональной занятости матери и ее семейного положения на массу тела новорожденного и риск преждевременных родов в городе Мончегорске Мурманской области за 30-летний период. Экология человека. 2014; 8: 3-12. [Kozlovskaya A.V., Odland J.Ø., Grjibovski A.M. Maternal occupation and marital status are associated with birth weight and risk of preterm birth in Monchegorsk (Murmansk region) during a 30-year period. Ekologiya cheloveka (Human Ecology). 2014; 8: 3-12. (in Russian)].

- Skjaerven R., Irgens L.M. Perinatal mortality and mother’s marital status at birth in subsequent siblings. Early Hum. Dev. 1988; 18(2-3):199-212. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-3782(88)90057-6.

- Statistics Norway. Live births, by parity, cohabitation status of mother 2002–2019. Available at: https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank/table/08451

- Rantakallio P., Oja H. Perinatal risk for infants of unmarried mothers, over a period of 20 years. Early Hum. Dev. 1990; 22(3): 157-69. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0378-3782(90)90182-I.

- Shapiro G.D., Bushnik T., Wilkins R., Kramer M.S., Kaufman J.S., Sheppard A.J., Yang S. Adverse birth outcomes in relation to maternal marital and cohabitation status in Canada. Ann. Epidemiol. 2018; 28(8): 503-9. e11. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.05.001.

Received 08.02.2021

Accepted 08.04.2021

About the Authors

Natalia A. Treskina, the Central Scientific Research Laboratory, Northern State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, Arkhangelsk; Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim. E-mail: natali163015@rambler.ru. ORCID: 0000-0002-2430-5197.51 Troitsky Ave., Arkhangelsk, 163000, Russia; NTNU, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway.

Vitaly A. Postoev, PhD, lecturer at the Department of Public Health, Health Care and Social Work, Director of the International School of Public Health, Northern State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, Arkhangelsk. E-mail: vipostoev@yandex.ru. ORCID: 0000-0003-4982-4169. 51 Troitsky Ave., Arkhangelsk, 163000, Russia.

Anna A. Usynina, PhD, Cand. Med. Sci, Associate Professor at the Department of Neonatology and Perinatology, Northern State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, Arkhangelsk. E-mail: perinat@mail.ru. ORCID: 0000-0002-5346-3047. 51 Troitsky Ave., Arkhangelsk, 163000, Russia.

Andrej M. Grjibovski, PhD, Director of the Central Scientific Research Laboratory, Northern State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, Arkhangelsk.

E-mail: andrej.grjibovski@gmail.com. ORCID: 0000-0002-5464-0498. 51 Troitsky Ave., Arkhangelsk, 163000, Russia.

Jon Ø. Odland, PhD, Professor at the Department of Global Health at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim. E-mail: jon.o.odland@ntnu.no. ORCID: 0000-0002-2756-0732.

For citation: Treskina N.A., Postoev V.A., Usynina A.A., Grjibovski A.M., Odland J.Ø. Sociodemographic factors influencing the health of pregnant women: changes

in the Arctic countries over the past decades.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 6: 5-13 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.6.5-13