The role of uterine artery embolization in the treatment of late postpartum hemorrhage

Objective: To investigate the characteristic features of late postpartum hemorrhage that required endovascular intervention.Breslav I.Yu., Kolotilova M.L., Grigoryan A.M., Barykina O.P., Skryabin N.V., Gaponenko E.A., Nigmatullina E.R.

Materials and methods: This is a retrospective analysis of medical records of 31 patients who were treated between 2006 to 2022. Inclusion criteria were late postpartum hemorrhage (24 h–42 days after delivery) and the use of uterine artery embolization (UAE).

Results: Bleeding started on day 8 (6;14) postpartum, including 20/31 (64.5%) on days 2–10, 9/31 (29%) on days 12–21, and 2/31 (6.5%) on days 35–38. Twenty-three of the 31 (74.2%) patients (subgroup I) underwent uterine vacuum aspiration. Continued blood loss of 1000 (600;1350) ml after vacuum aspiration was an indication for UAE. Surgical hemostasis was performed in 1/23 (4.3%) patients after UAE. A complicated course of the postoperative period was observed in 4/23(17.4%) patients. In 8/31 (25.8%) patients (subgroup II), UAE was performed in the first stage with an initial blood loss of 650 (400;2000) ml. The postpartum period was uneventful and the patients were discharged on the fourth day.

Conclusion: Massive late postpartum hemorrhage is rare. UAE is effective in stopping late postpartum hemorrhage in the absence of residual placental tissue in the uterine cavity established by echography.

Keywords

Due to the development of clinical guidelines, systematization of medical care, improvement of medical, surgical and endovascular treatments of obstetric hemorrhage, the proportion of maternal deaths attributed to obstetric hemorrhage in the Russian Federation has decreased from 22% in 2001 to 6.2% in 2020. At the same time, the maternal mortality rate has decreased from 36.5 per 100,000 live births (2001) to 11.2 per 100,000 live births (2020). It can be assumed that this reduction was due to the decrease in the frequency of massive obstetric hemorrhages: while 20 years ago they were the most frequent causes of maternal death, now they are the third-leading cause of maternal death.

There is a distinction between early (primary) and late (secondary) postpartum hemorrhage. Primary postpartum hemorrhage appears during the first 24 hours after delivery and secondary occurs for more than 24 hours and up to 12 weeks after delivery [1].

According to the Ministry of Health, the overall incidence (without division into early and late) of hemorrhage in the postpartum period in 2021 was 1.17%; hemorrhage due to clotting disorders was 0.047% [2].

The main cause of early postpartum hemorrhage is uterine contractility disorder - uterine atony (90%); other factors (trauma of the birth canal, retained parts of the placenta, or hemostasis disorders) account for approximately 10%.

The leading role in the etiology of late postpartum hemorrhage is played by: placental tissue, uterine subinvolution, postpartum infection, hereditary hemostasis defects (Clinical guidelines, 2021). Despite their relative rarity, these bleedings can lead to fatal outcomes due to their unexpectedness and massiveness [3].

There is a generally accepted sequence for the obstetrician gynecologist to follow when bleeding occurs during a cesarean section or immediately after delivery. In late postpartum hemorrhage, such an algorithm is not specified, except for the point about the need to evacuate retained placental tissue. There is no mention of the possibility of endovascular hemostasis as an alternative to surgical removal of the uterine contents if there is no retained placental tissue [1].

Compared to the multitude of publications on early postpartum bleeding, the current literature lacks studies on the treatment of secondary hemorrhage; only case reports and theoretical reviews are available [4–6]. Information on the use of endovascular interventions to stop late postpartum hemorrhage is extremely scarce. Notable is the study by Rodchenkova et al. (2019), who studied the treatment outcomes of 103 patients with late postpartum hemorrhage. In 15 patients, endovascular occlusion of the uterine arteries was used with a positive outcome. [7]. N.I. Tikhomirova et al. (2011) described an observation of successful stopping of late coagulopathic postpartum hemorrhage by uterine artery embolization [8]. A. Belousova et al. (2018) used endovascular occlusion of the uterine arteries in 2 patients: in one due to continued hemorrhage after instrumental uterine evacuation, in the other due to the ineffectiveness of conservative drug therapy [9]. The endovascular procedure was preceded by uterine curettage in 17 of the 18 patients described above.

The present study aimed to investigate the characteristic features of late postpartum hemorrhage that required endovascular intervention.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study was conducted at the MD Group Clinical Hospital, Moscow. Data from 31 patients with late postpartum bleeding who were delivered in 2006–2022 were analyzed, including 21 delivery notes and 38 inpatient medical records (these patients developed hemorrhage after discharge from the hospital where the delivery occurred, which required repeated hospitalization). Deliverys took place in different maternity hospitals in Moscow and at the Lapino Clinical Hospital. The endovascular intervention was performed at the MD Group Clinical Hospital in Moscow, the Center for Family Planning and Reproduction of the Moscow Department of Health and the Lapino Clinical Hospital. Inclusion criteria were late postpartum hemorrhage (24 h–42 days after delivery); use of uterine artery embolization (UAE) during the treatment.

Non-inclusion criteria were placenta accreta spectrum, including when it was left in situ after fetal extraction; uterine rupture; gestational age at the time of delivery less than 22 weeks; absence of external hemorrhage with hematometra or retained placental tissue detectable by echography.

Birth histories were used to assess somatic, gynecological, obstetric history, timing and methods of delivery, indications for a real cesarean section, course of labor, children's weight, features of the postpartum period complicated by late hemorrhage. Inpatient medical records (in the absence of data in delivery notes) were used to obtain information about the time of hemorrhage onset, its massiveness, the extent of surgery, the course of the postoperative period, and the need for blood products. Histological examination was performed using hematoxylin-eosin and Van Gieson staining.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables that showed normal distribution were expressed as means (M) and standard deviation (SD) and presented as M (SD); otherwise, the median (Me) with the interquartile range (Q1; Q3) was reported. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 31.5 (4) years. The somatic history was complicated in 19/31 (61.3%) patients, coagulopathies were diagnosed in 2/19 (10.5%) including Willebrand disease and heterozygous mutation of the F2 gene. Hysteroscopy and fractional diagnostic curettage were used in 4/31 (12.9%) patients. Spontaneous pregnancy occurred in 26/31 (83.9%) patients and in 5/31 (16.1%) as a result of assisted reproductive technology. There was a uterine scar after 1 or 2 caesarean sections in 5/31 (16.1%) patients. A history of uterine curettage was noted in 12/31 (38.7%) patients. The present birth was first in 12/31 (38.7%), second in 12/31 (38.7%), and third in 3/31 (9.7%) patients; 4/31 (12.9%) patients had high parity (fourth and sixth births). Multiple pregnancies occurred in 5/31 (16.1%), one triplet, and 4 twin pregnancies. The gestational age at the time of delivery was 39 (37;39) weeks. Preterm birth at 33-36 weeks occurred in 5/31 (16.1%) and full-term in 26/31 (83.9%). Premature rupture of membranes occurred in 5/31 (16.1%) patients, of whom 3/5 (60%) were subsequently diagnosed with uterine subinvolution. A ruptured membrane of more than 12 hours was observed in 3/31 (9.7%) patients.

Nineteen of 31 (61.3%) patients gave birth spontaneously and 12/31 (38.7%) underwent a cesarean section. In the early postpartum period, 7/19 (36.8%) patients underwent bimanual separation of the placenta and isolation of the afterbirth, bimanual examination for complete or partial placenta accreta spectrum, placental or membrane defects. Sixteen of 19 (84.2%) patients were discharged on day 3 (3;4) after delivery. In them, hemorrhage occurred on the fifth-38th day after delivery. In 3/19 (15.8%), hemorrhage developed on days 2 to 3 after delivery.

Elective and emergency caesarean delivery was performed in 6/12 (50%) and 6/12 (50%) patients, respectively. The indications for elective cesarean section were uterine scar after cesarean section and the patient's refusal to deliver spontaneously, pregnancy after IVF in a 40-year-old primipara, fetal breech presentation, transverse fetal position, and severe preeclampsia. The indications for emergency surgery were multiple pregnancies, uterine scar dehiscence after cesarean section, severe preeclampsia, and acute fetal hypoxia. Eight out of 12 (66.7%) patients were discharged on day 7 (5;8) after delivery. In them, hemorrhage occurred on days 13–19 postpartum; in 4/12 (33.3%) patients, hemorrhage developed on days 5–6 postpartum.

Patients complained of heavy vaginal bleeding on day 8 (6;14) postpartum: 20/31 (64.5%) of them on days 2–10, 9/31 (29%) on days 12–21, and 2/31 (6.5%) of them on days 35–38.

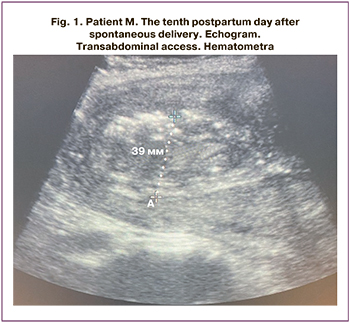

Delayed uterine involution was observed in 29/31 (93.5%) patients. In patients who developed hemorrhage on days 2–10 postpartum, the uterus was 130 (119;143) mm long, 111 (101;120) mm wide, 86 (79;92) mm anteroposterior dimension, and 37 (28;51) mm uterine cavity length. In patients who developed hemorrhage on days 11–21, the length was 122 (121;132) mm, the width was 116 (111;126) mm, anteroposterior dimension was 94 (92;96) mm and uterine cavity length was 41 (35;49) mm (Fig. 1).

In 1/31 (3.2%) patients bleeding began on day 35 postpartum, uterine dimensions were 55×49×66 mm, the cavity was not dilated, there was a 23×22 mm mass on the posterior wall with slow blood flow on color Doppler.

In 1/31 (3.2%) patients who underwent vacuum aspiration on day 23 after spontaneous delivery due to hematoma (histologically, placental polyp with suppuration), bleeding began on day 38 postpartum, the dimensions were 51×40×53 mm, M-echo 7 mm.

Twenty-three of 31 (74.2%) patients (subgroup I) underwent removal of uterine contents by vacuum aspiration under general combined anesthesia. Given the ongoing bleeding of 1000 (600;1350) ml, UAE was performed. In 13/23(56.5%) patients, blood loss before UAE was 400-1000 ml, in 10/23(43.5%) it was 1200-3900 ml (2500, 3000, 3900 ml).

Of 23/31 (74.2%) patients (subgroup I) who underwent removal of uterine contents using vacuum aspiration before UAE, 18/23 (78.3%) had the material sent for histological examination. At pathomorphological examination, in 16/18 (88.9%) patients, there were dystrophically altered and necrotized fragments of decidual tissue with circulatory alterations and reactive inflammatory infiltration among blood in the material evacuated from the uterine cavity; a placental polyp was found in 2/18 (11.1%) patients; signs of endometritis were detected in 8/16 (50%) patients.

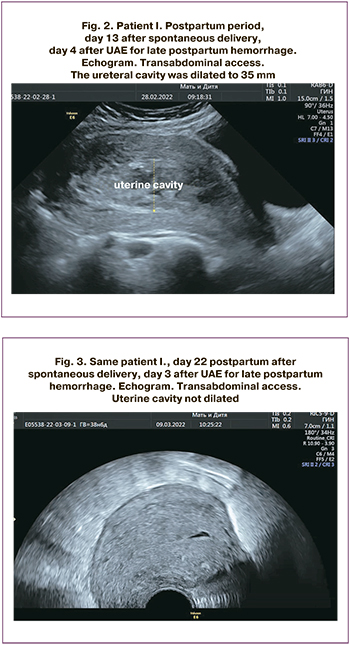

UAE was performed in 8/31 (25.8%) patients (subgroup II) without prior removal of uterine contents and an initial blood loss of 650 (400;2000) ml. In these patients, bleeding started on days 2–13 postpartum. According to echography, there was no retained placental tissue in the uterine cavity.

In subgroup I, the pre-UAE and post-UAE hemoglobin level was 78±23 and 89±18 g/l; in subgroup II, the pre-UAE and post-UAE hemoglobin level was 83±19 and 93±7 g/l, respectively.

To restore globular volume and blood clotting potential, 14/23 (60.9%) patients in subgroup I received 570 (473;840) ml of donor red blood cells, 17/23 (73.9%) patients received 1180 (600;1340) ml of fresh frozen plasma. In subgroup II, 3/8 (37.5%) patients received 530 (400;545) ml of donor red blood cells and 5/8 (62.5%) patients received 960 (900;1170) ml of fresh frozen plasma.

The postoperative period in all patients in subgroup II was without complications and they were discharged on day 4 (Fig. 2, 3).

In subgroup I, 18/23 (78.3%) patients had an uneventful postoperative period and were discharged on day 6 (3;8).

UAE proved to be ineffective in one patient in subgroup I. After uterine curettage and UAE, the blood loss was 2400 ml, bleeding resumed 1 h later. The patient underwent relaparotomy with uterotomy, suturing of placental site vessels, uterine and lower uterine segment compression sutures. Total blood loss was 3400 ml, the bleeding stopped. She was discharged on day 10 in satisfactory condition.

In the remaining patients, UAE was effective, bleeding was stopped. However, 4 patients in subgroup I had a complicated postpartum period, which required intrauterine intervention.

One patient complained of pelvic pain on day 10 after UAE, the uterine cavity was dilated to 60 mm. She underwent hysteroscopy and vacuum aspiration of 200 ml of hemolysed blood. The patient was discharged on day 2. This observation cannot be regarded as an ineffective UAE, since there was no external bleeding, deposition of a certain volume of blood could have occurred before or during the UAE.

One patient had fever up to 38°C on day 11 after UAE; on ultrasound examination, the uterine cavity was dilated to 25 mm, 50 ml of clots were removed. She was discharged on day 4.

One patient on day 23 after UAE had a fever of 39°C, the uterine cavity was dilated to 37 mm. Repeated vacuum aspiration was performed. The patient was discharged on day 2;

One patient on day 2 after UAE had fever up to 37.6°C; the uterine cavity was dilated to 18 mm. The uterine contents using vacuum aspiration. The blood loss was minimal (5 ml). She was discharged on day 3.

Discussion

Compared to early postpartum hemorrhage (4–6% of all deliveries), which is more associated with life-threatening conditions and maternal mortality, late hemorrhage occurs less frequently (0.47–1.44%), requires fewer blood transfusions, and patients remain hemodynamically stable longer [10–12].

It is reasonable to divide secondary postpartum hemorrhage into 2 groups according to etiology: 1) uterine (uterine subinvolution, placenta accreta spectrum, uterine myoma, uterine vascular abnormalities, choriocarcinoma); 2) mixed (blood clotting disorders, vaginal ruptures, and hematomas).

Of greatest interest are the uterine forms of secondary postpartum hemorrhage, the main cause of which, according to our data, was uterine subinvolution detected by ultrasound in 29/31 (93.5%) patients.

Delayed uterine involution was confirmed by transabdominal echography, which recorded a delayed decrease in uterine length, width, and anteroposterior size of 1-3 cm above normal and expansion of the uterine cavity above 30 mm.

Histological verification of diagnosis was possible in 18/31 (58.1%) patients who underwent removal of uterine contents by vacuum aspiration and the material was sent for pathomorphological examination. Necrotized decidual tissue and placental polyps were histologically confirmed in 16/18 (88.9%) and 2/18 (11.1%) patients, respectively

In 8/16 (50%) of our study patients, uterine subinvolution was of inflammatory nature and developed against the backdrop of endometritis, characterized by a slow rate of reduction in uterine size, which is consistent with the findings of the domestic authors, who found acute endometritis in 60.8% of patients [9]. Postpartum endometritis is often associated with premature rupture of the membranes, prolonged rupture of the membranes, impaired myometrial contractile activity, and, as a consequence, retained parts of placenta in the uterus [13]. Our data on the frequency of prolonged rupture of membranes of more than 12 hours differ from those in the international literature about its significance in uterine subinvolution.

A special role in the development of secondary postpartum hemorrhage is played by uterine vascular anomalies. Arteriovenous malformation (pseudoaneurysm) is a local proliferation of an artery and venule with the formation of a connective fistula. In the majority of patients, arteriovenous malformations are diagnosed after pregnancy resulting from surgical intervention, including uterine curettage or trophoblastic disease [14]. In our study, 1/31 (3.2%) patient had a vascular malformation of the posterior uterine wall combined with inflammation. Hereditary defects of hemostasis genes were detected in 2/31 (6.5%) patients.

The Clinical Guidelines (2021) for the treatment of secondary hemorrhage state that if retained placental tissues are detected, they should be surgically removed. This emphasis can be explained by the fact that, according to the literature, retained placental tissue is the most common cause of secondary hemorrhage [1, 12]. In our study, it occurred in 2/18 (11.1%) with histological confirmation or in 2/31 (6.5%) of the patients included in the study. However, despite the infrequent detection of retained placental tissue in the uterus, the first step in 23/31 (74.2%) patients in our study was hysteroscopy, vacuum aspiration of the contents of the uterine cavity. The reason for endovascular hemostasis is ongoing bleeding, which in 8/31 (25.8%) of the women in labor was stopped at a blood loss of 650 (400;2000) ml without vacuum aspiration of the uterine contents.

Cessation of bleeding was achieved in 30/31 (96.8%) of our patients. In 1/31 (3.2%) women who gave birth, the ongoing bleeding after UAE required a laparotomy, the application of compression sutures to the uterus to stop the bleeding.

Four out of 30 (13.3%) patients on days 2, 10, 11, and 23 developed fever up to 39°C and pelvic pain; the uterine cavity was dilated to 25–60 mm. They underwent removal of uterine contents using vacuum aspiration, blood loss 50–200 ml. The pathomorphological report confirmed the presence of necrotized decidual tissue with leucocytic infiltration. Vacuum aspiration of the uterine cavity contents was performed before endovascular blockade of the uterine arteries in all patients with a complicated postoperative period. None of the 8 patients who had UAE as a unimodal surgical treatment required such a procedure.

Conclusion

Massive late postpartum hemorrhage is rare; 31 cases were recorded over 17 years at 3 clinical sites. In the majority (64.5%) of puerperal women, bleeding started on days 2–10 postpartum. Patients who developed bleeding between days 2 and 21 postpartum had uterine subinvolution confirmed by an ultrasound examination. The most significant increase was observed in transverse size of the uterine cavity. UAE is effective in stopping late postpartum bleeding without prior emptying of the uterine cavity in the absence of retained placental tissue diagnosed by echography.

References

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Послеродовое кровотечение. М.; 2021. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Postpartum hemorrhage. 2021(in Russian)].

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Основные показатели здоровья матери и ребенка, деятельность службы охраны детства и родовспоможения в Российской Федерации. М.: Департамент мониторинга, анализа и стратегического развития здравоохранения, ФГБУ «Центральный научно-исследовательский институт организации и информатизации здравоохранения». 2022. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. The main indicators of maternal and child health, the activities of the child protection and obstetric services in the Russian Federation. M.: Department of monitoring, analysis and strategic development of healthcare. Federal State Budgetary Institution "Central Research Institute of Organization and Informatization of Healthcare" of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Moscow; 2022 (in Russian)].

- Farley N.J., Kohlmeier R.E. A death due to subinvolution of the uteroplacental arteries. J. Forensic Sci. 2011; 56(3): 803-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01726.x.

- Курцер М.А., Бреслав И.Ю., Кутакова Ю.Ю., Лукашина М.В., Панин А.В.,Бобров Б.Ю. Гипотонические послеродовые кровотечения. Использование перевязки внутренних подвздошных артерий и эмболизации маточных артерий в раннем послеродовом периоде. Акушерство и гинекология. 2012; 7: 36-41. [Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Kutakova Yu.Yu., Lukashina M.V.,Panin A.V., Bobrov B.Yu. Hypotonic postpartum hemorrhage. Use of internal iliac artery ligation and uterine artery embolization in the early postpartum period. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012; 7: 36-41 (in Russian)].

- Сюткина И.П., Хабаров Д.В., Ракитин Ф.А., Щедрова В.В. Комплексная оценка периоперационного периода при эмболизации маточных артерий на основе анализа маркеров стресс-реакции и допплерометрического контроля редукции маточного кровотока. Акушерство и гинекология. 2018; 10: 64-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2018.10.64-70. [Syutkina I.P., Khabarov D.V., Rakitin F.A., Shchedrova V.V. Comprehensive assessment of the perioperative period during uterine artery embolization based on the analysis of stress response markers and Doppler control of uterine blood flow reduction. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; 10: 64-70(in Russian)].

- Белоусова А.А., Арютин Д.Г., Токтар Л.Р., Ваганов Е.Ф., Холмина Н.Ю. Поздние послеродовые кровотечения. Акушерство и гинекология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2019; 7(3): 64-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2303-9698-2019-13009. [Belousova A.A., Aryutin D.G., Toktar L.R.,Vaganov E.F., Kholmina N.Yu. Late postpartum hemorrhage. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya: novosti, mneniya, obuchenie/Obstetrics and Gynecology: News, Opinions, Training. 2019; 7(3): 64-69. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2303-9698-2019-13009.

- Родченкова А.А., Мельник П.С., Арютин Д.Г. Поздние послеродовые кровотечения. Акушерство и гинекология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2019; 7(Приложение): 107-14. https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2303-9698-2019-13915. [Rodchenkova A.A., Melnik P.S., Aryutin D.G. Late postpartum hemorrhage. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya: novosti, mneniya, obuchenie/Obstetrics and Gynecology: News, Opinions, Training. 2019; 7(3) Suppl.: 107-114.(in Russian)]. 10.24411/2303-9698-2019-13915.

- Тихомирова Н.И., Белозеров Г.Е., Олейникова О.Н., Черная Н.Р.,Даниелян Л.А., Гелашвили С.Т. Опыт применения эмболизации маточных артерий в лечении кровотечений, вызванным плацентарным полипом. Неотложная медицинская помощь. 2011; 1: 44-6. [Tikhomirova N.I.,Belozerov G.E., Oleinikova O.N., Chernaya N.R., Danielyan L.A.,Gelashvili S.T. Experience in the use of uterine artery embolization in the treatment of bleeding caused by placental polyps. Neotlozhnaya medicinskaya pomoshh'/Urgent medical care. 2011; 1: 44-46(in Russian)].

- Белоусова А.А., Арютин Д.Г., Тониян К.А., Токтар Л.Р., Добровольская Д.А., Духин А.О. Поздние послеродовые кровотечения: актуальность проблемы и пути ее решения. Акушерство и гинекология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2018; 3: 119-26. [Belousova A.A., Aryutin D.G., Toniyan K.A., Toktar L.R., Dobrovolskaya D.A., Duhin A.O. Late postpartum hemorrhage: the relevance of the problem and ways to solve it. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya: novosti, mneniya, obuchenie/Obstetrics and Gynecology: News, Opinions, Training. 2018; 3(21): 119-126 (in Russian)].

- Loya M.F., Garcia-Reyes K., Gichoya J., Newsome J. Uterine artery embolization for secondary postpartum hemorrhage. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021; 24(1): 100728. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tvir.2021.100728.

- Cunningham K., Sullivan M., Ahmed S., Svokos A. Secondary postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine artery pseudoaneurysm. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. J. 2021; 12(2): 49-51.

- Chen C., Lee S.M., Kim J.W., Shin J.H. Recent update of embolization of postpartum hemorrhage. Korean J. Radiol. 2018; 19(4): 585-96.https://dx.doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2018.19.4.585.

- Groom K.M., Jacobson T.Z. A comprehensive textbook of postpartum hemorrhage: an essential clinical reference for effective management. 2nd ed. London: Sapiens Publishing; 2012.

- Bardou P., Orabona M., Vincelot A., Maubon A., Nathan N. Uterine artery false aneurysm after caesarean delivery an uncommon cause of post-partum haemorrage. Ann. Fr. Anesth. Reanim. 2010; 29(12): 909-12.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annfar.2010.09.014.

Received 07.10.2022

Accepted 21.11.2022

About the Authors

Irina Yu. Breslav, Dr. Med. Sci., Head of the Department of Obstetric Pathology of Pregnancy, MD GROUP Hospital, +7(495)331-44-85, irina_breslav@mail.ru,https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0245-4968, 24/1 Sevastopol Ave., Moscow, 117209, Russia.

Marina L. Kolotilova, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor at the Human Pathology Department, Institute of Biodesign and Modeling of Complex Systems, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), +7(903)201-75-31, Kolotilovaml@hotmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7270-8671,

8-2 Trubetskaya str., Moscow, 119991, Russia.

Ashot M. Grigoryan, PhD, Head of the Interventional Cardiology Department, Lapino Clinical Hospital, +7(495)526-60-60, a.grigoryan@mcclinics.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9226-0130, 111, 1-st Uspenskoe highway, Lapino, Moscow region, 143081, Russia.

Olga P. Barykina, pathologist, Head of the Department of Anatomic Pathology, MD GROUP Hospital, +7(495)332-20-22, medslovar@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4943-0741, 24/1 Sevastopol Ave., Moscow, 117209, Russia.

Nikolay V. Scryabin, Pathologist at the Department of Anatomic Pathology, MD GROUP Hospital, +7(495)332-20-22, hranitelkr@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8247-7563, 24/1 Sevastopol Ave., Moscow, 117209, Russia.

Ekaterina A. Gaponenko, MD, Diagnostic Medical Sonographer, MD GROUP Hospital, +7(495)331-44-85, Gaponenko.m.d@gmail.com,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1593-9953, 24/1 Sevastopol Ave., Moscow, 117209, Russia.

Elina R. Nigmatullina, Resident at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of General Medicine, Bashkir State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia; MD GROUP Hospital, +7(960)866-50-50, elinanig@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2006-6210, 24/1 Sevastopol Ave., Moscow, 117209, Russia.

Corresponding author: Irina Yu. Breslav, irina_breslav@mail.ru

Authors' contributions: Breslav I.Yu. – conception and design of the study, analysis of observations with late postpartum hemorrhage, manuscript drafting, design of illustrative material; Kolotilova M.L. – manuscript drafting; Grigoryan A.M. – performing endovascular intervention in patients with late postpartum hemorrhage, providing illustrative material; Barykina O.P. – pathomorphological examination of uterine cavity aspirate; Skryabin N.V. – pathomorphological study of uterine cavity aspirate, compilation of photographic materials; Gaponenko E.A. – echography, provision of digital images; Nigmatullina E.R. – data collection and statistical analysis of labor histories and in-patient records of patients with late postpartum hemorrhage.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the N.I. Pirogov RNRMU.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Breslav I.Yu., Kolotilova M.L., Grigoryan A.M.,

Barykina O.P., Skryabin N.V., Gaponenko E.A., Nigmatullina E.R.

The role of uterine artery embolization in the treatment of late postpartum hemorrhage.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 12: 100-106 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.239