Realization of reproductive potential in patients with atypical hyperplasia and stage I endometrial cancer

Aim To determine the most effective way of getting pregnant for patients with a history of initial stages of endometrial cancer.Dzhanashvili L.G., Nazarenko T.A., Balakhontseva O.S., Martirosyan YA.O., Pronin S.M., Kalinina E.A., Biryukova A.M.

Materials and methods The study comprised 77 patients of reproductive age who were seeking to conceive after achieving remission or required retrieval and cryopreservation of reproductive material before starting cancer treatment. The study participants were divided into groups classified by the presence of stage I endometrial cancer (group 1, n=48) and atypical endometrial hyperplasia (group 2, n=29).

Results Seventeen (35.4%) and 6 (20.7%) women in groups 1 and 2, respectively, had polycystic ovary syndrome with severe endocrine and metabolic dysfunctions. There was a lack of unified approaches to counseling and management of this category of patients, which was associated with a high recurrence rate. Procurement of reproductive material after treatment of the present disease resulted in a limited number and poor quality of oocytes/embryos. This observation implied the need for retrieval and cryopreservation of reproductive material before starting treatment. A low pregnancy rate of 21.7% per attempt was probably associated with impaired embryo implantation and endometrial receptivity following exposure to the levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

Conclusion The pregnancy rate after 69 IVF attempts was 21.7% (15 pregnancies). The low pregnancy rate and the questions encountered during the treatment suggest the need for further studies.

Keywords

Cancer of the corpus uteri (CCU) accounts for 5.3% of oncological diseases among women aged 30-59, most of whom are of reproductive age [1]. In the past, surgery, including hysterectomy and total hysterectomy was the only option for the management of patients with initial stages of CCU. Recently, in the absence of myometrial invasion detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), gynecological oncologists have successfully used hormone therapy [2] as an independent treatment modality, which allows patients to realize their reproductive potential after achieving stable remission [3]. The Clinical Guidelines of the Russian Society of Clinical Oncology suggest that surgery is the most effective treatment for CCU, regardless of stage [4]. Still, young patients with well-differentiated CCU may undergo organ-sparing treatment, which should be provided in institutions having relevant experience [5].

Clinical practice shows that recently, young women with stage I CCU without myometrial invasion undergo conservative treatment aimed at achieving endometrial atrophy, eliminating foci of atypical cells secondary to local and systemic hypoestrogenism. The therapy lasts as a rule from 6 to 12 months being successful in most cases, and oncologists allow the woman to become pregnant. However, the treatment of CCU requires unification and objectification. Oncologists use various treatment regimens: monotherapy with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist or medroxyprogesterone, levonorgestrel–containing intrauterine device (IUD), or a combination thereof. Antiestrogens are also prescribed, both as monotherapy and in combination with the above drugs [6]. The current literature is lacking sufficient coverage of the effectiveness of various types of treatment and the recurrence rate.

Planning conservative fertility-sparing treatment, oncologists often do not take into account the patient’s reproductive capabilities, her ability to become pregnant, both independently and when using assisted reproduction methods. Moreover, the currently available literature is lacking information about the state of the reproductive system of young CCU patients, management strategy aimed to preserve their reproductive function, time to restore the implantation properties of the endometrium after therapy; namely, the competence of the endometrium is a prerequisite for the successful implantation and development of pregnancy.

The lack of sufficient information prompted us to share our first experience in treating patients with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma who sought to preserve reproductive material to realize their reproductive potential after treatment is completed.

This study aimed to determine the most effective way of getting pregnant for patients with a history of initial stages of endometrial cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer or atypical hyperplasia were referred by a gynecological oncologist to either preserve the reproductive material before the onset of therapy or to fulfill their reproductive function after achieving disease remission. Inclusion criteria were: reproductive age of patients, preserved ovarian reserve, absence of myometrial invasion on MRI, signed informed consent, the conclusion of the gynecological oncologist about the absence of contraindications to assisted reproductive technology programs, and the patient’s desire to fulfill the reproductive function.

The characteristic feature of our study was that the decision about study enrollment had to been made already at the first consultation, and no time was given for a preliminary patient examination. In total, 77 patients aged 25 to 50 years were referred for consultation from October 2018 to August 2019; the mean age was 36.6 (2.8) years. Stage I CCU and atypical endometrial hyperplasia were diagnosed in 48 and 29 patients, respectively. Eight patients were considered inappropriate for the preservation of the reproductive material or programs aimed at the implementation of the reproductive function after treatment completion due to their late age and diminished ovarian reserve. Eleven women aged 24 to 36 were recommended to undergo treatment of the present illness, re-consultation after treatment completion, and achievement of stable remission. This decision was due to the following arguments: young age, polycystic ovaries according to ultrasound and high ovarian reserve, severe endocrine and metabolic disorders, lack of a sexual partner, and focus on delayed childbirth. In total, IVF programs were conducted in 41 women. Four of them underwent ovarian stimulation, retrieval, and cryopreservation of oocytes/embryos before the onset of therapy. Another four women underwent ovulation stimulation, followed by retrieval and cryopreservation of reproductive material during treatment. Thirtyone patients received IVF treatment with embryo transfer during a fresh IVF cycle after cancer treatment completion. In 2 patients, the transfer of previously preserved embryos was carried out.

The patients underwent ovarian stimulation with GnRH-antagonist based ovarian stimulation protocols, transvaginal ultrasound-guided follicle aspiration, oocyte retrieval, and cryopreservation or fertilization, embryo culture, embryo cryopreservation, embryo transfer, and cryopreservation of the remaining embryos. During ovarian stimulation, monitoring was performed by transvaginal ultrasound examination and measurement of serum hormone concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2013 and SPSSV22.0. The distribution of continuous variables was tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Quantitative variables showing normal distribution were expressed as means (M) and standard deviation (SD) and evaluated with the Student’s t-test. Qualitative variables were summarized as counts and percentages and assessed by Fisher’s exact test. Differences between the groups were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Medical history and clinical and laboratory parameters of the study patients

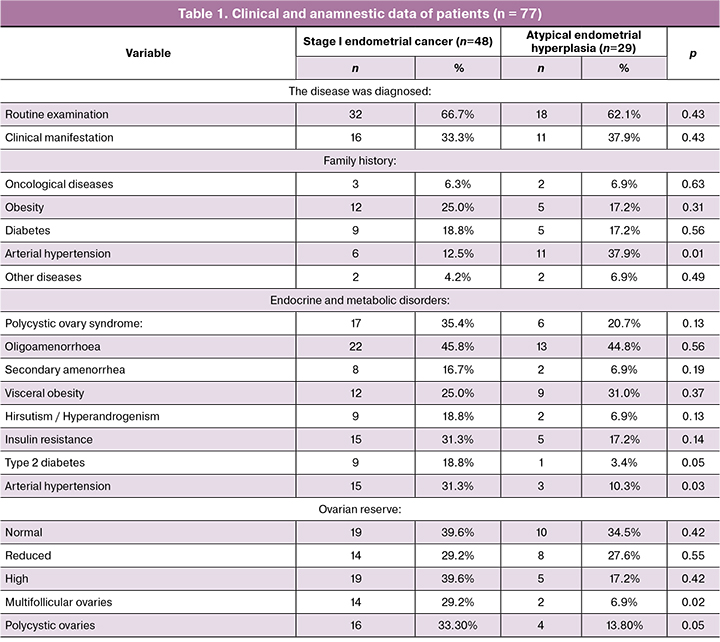

The results of clinical and laboratory examination and anamnestic data of patients are presented in table 1.

At the time of study recruitment, the mean age of patients with stage 1 endometrial cancer and atypical endometrial hyperplasia was 37.2 (1.1) and 36.6 (1.3) years, respectively. No differences were observed between both groups regarding age, anamnestic data, and the state of the ovarian reserve. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) was diagnosed in 35.4% and 20.6% of patients with endometrial cancer and endometrial hyperplasia, respectively.

Patients with endometrial cancer were three times more likely to have PCOS related endocrine and metabolic disorders than patients with endometrial hyperplasia [7]. Women with PCOS are known to have a 2.7 times greater risk of developing endometrial cancer [8]. Our findings have fully confirmed this observation.

Type I endometrial cancers are generally slowgrowing, less likely to spread, and have a favorable prognosis provided that patients undergo a radical hysterectomy. The decision to remove ovaries is made on an individual basis during surgery [4]. In our case, patients were treated conservatively to realize their reproductive potential after treatment completion. However, patients with oligo-amenorrhea are unable to achieve spontaneous pregnancy due to the lack of ovulation, which necessitates the use of assisted reproduction. Secondly, the presence of PCOS with severe endocrine and metabolic disorders confer a high risk of cancer recurrence [7]. All of the above suggests the need for new methods for the treatment of endocrine-metabolic disorders in these patients and the prevention of the disease recurrence.

Assessment of cancer treatment modalities

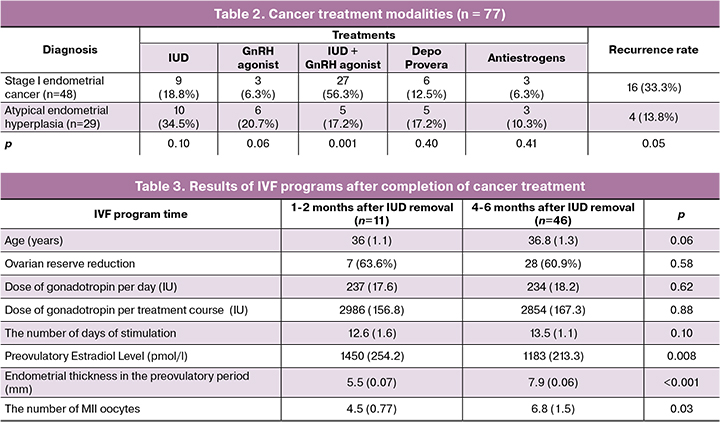

Analysis of patients’ management showed a lack of a unified approach to the choice of treatment modality. Although all treatments resulted in the desired outcomes, the recurrence rate of endometrial cancer was 33.3%, which undoubtedly emphasizes the need for unified treatment protocols that ensure remission, reduce, if possible, the risk of recurrence and preserve fertility.

Analysis of treatment aimed at retrieval and storage of reproductive material or fertility preservation

Before starting treatment, IVF cycles with retrieval and cryopreservation of reproductive material were performed in 4 women aged 37.5 (1.2) years. Two of them had a normal ovarian reserve, one had diminished ovarian reserve due to late reproductive age, and one patient had PCOS. All patients underwent ovulation stimulation, followed by retrieval and cryopreservation of reproductive material. Daily doses of gonadotropins varied from 150 to 300 IU, depending on the ovarian reserve, the dose per course was 2154 (178.7) IU, the pre-ovulatory level of estradiol was 2950 (158.2) pmol/L. Cryopreservation was performed in two patients (16 and 17 oocytes), in a patient of late reproductive age one embryo was cryopreserved, and 11 embryos were cryopreserved in the patient with PCOS. To reduce estradiol levels after a follicular puncture, a GnRH antagonist was prescribed at a dose of 0.5 mg for 3-4 days.

In the present study, the transfer of cryopreserved embryos was performed in 2 patients 3-6 months after the end of treatment. This resulted in ectopic pregnancy in one of the patients.

Fifty-seven embryo transfers in a fresh cycle were carried out in 31 women after completing treatment. The results of the treatment are presented in table 3.

The study findings demonstrated a significantly lower number of retrieved oocytes compared with patients who underwent preliminary cryopreservation: before treatment 11.2, after 1-2 months 4.5, after 4-6 months 6.8. The best results were obtained in women with normal ovarian reserve when ovarian stimulation was carried out before the onset of therapy.

The need for preliminary retrieval and cryopreservation of oocytes/embryos in young women before the onset of gonadotoxic cancer therapy is recommended in clinical guidelines and documents adopted in many countries [8]. The hormone therapy used for the treatment of uterine cancer and atypical hyperplasia is not gonadotoxic. Nevertheless, in this study, despite limited clinical data, there was a clear tendency to decrease the number of mature oocytes during stimulation in the first cycles after the extraction of the IUD. This observation indicates the need for time to restore the reproductive system after hormonal therapy. In this regard, we consider it useful to perform preliminary cryopreservation of oocytes/embryos before the onset of treatment. This is especially important in cases of initially low ovarian reserve and the presence of endometrial cancer when treatment can take a long time.

Also, during the first months after the removal of the IUD, a significant portion of women (67.0%) were found to have a thin endometrium and its inadequate transformation during the induced cycle, which, in turn, may become a cause of a low pregnancy rate. Our experience showed that during the first two months after completion of therapy, there was insufficient thickness and transformation of the endometrium. During 2-4 cycles, 30 women underwent ultrasound monitoring. The growth of the dominant follicle and ovulation in the preovulatory period was associated with an endometrial thickness of 5.5 (1.2) mm, while there was no characteristic three-layer structure. This fact indicates the need to search for markers of endometrial implantation competency.

Achieving pregnancy after remission following conservative treatment of endometrial cancer is the most complex, controversial, and debatable issue. Current literature has reported a successful pregnancy in patients with uterine cancer after hormonal therapy [9]. However, there are no reliable statistics on pregnancy rates, their course, and childbirth. It is not clear when, after the completion of treatment, pregnancy occurs. The importance of this issue consists, on the one hand, in understanding the endometrial implantation competency and development of a pregnancy, and on the other hand, in the risk of disease recurrence. Even more challenging is the situation when there is a need for IVF with the transfer of cryopreserved embryos or in fresh treatment cycles. What is the most favorable period after completion of treatment, how to assess the adequacy of the secretory endometrium, can hormone therapy, especially estrogens, be administered during a transfer of thawed embryos? There is no evidence to answer these questions.

Conclusions

- An increasing need for rehabilitation of the reproductive function of patients with atypical hyperplasia and stage I endometrial cancer is a relevant issue.

- Hormone therapy is effective in achieving disease remission, but there is an urgent need for standardization of treatment protocols.

- Cryopreservation of oocytes/embryos before the onset of therapy for the present disease may be recommended, especially in patients with initially diminished ovarian reserve and a limited number and poor-quality oocytes obtained after treatment completion.

- There is an urgent need to develop comprehensive management for patients with endometrial I cancer or atypical endometrial hyperplasia who have PCOS and severe endocrine-metabolic disorders.

- It is necessary to specify the timing of pregnancy after completion of treatment based on markers predicting endometrial receptivity for implantation.

References

- Каприн А.Д., Старинский В.В., Петрова Г.В., ред. Злокачественные новообразования в России в 2017 году (заболеваемость и смертность). М.: МНИОИ им. П.А. Герцена – филиал ФГБУ «НМИРЦ» Минздрава России; 2018. [Kaprin A.D., Starinsky V.V., Petrova G.V., eds. Malignant neoplasms in Russia, in 2017 (morbidity and mortality). Moscow: MNIOI im. P.A. Gertsena - filial FGBU “NMIRTs” Minzdrava Rossii; 2018.(in Russian).]

- Чулкова О.В., Новикова Е.Г., Пронин С.М. Органосохраняющее и функционально щадящее лечение начального рака эндометрия. Опухоли женской репродуктивной системы. 2007; 1-2: 50-3. [Chulkova O.V., Novikova Ye.G., Pronin S.M. Organ-preserving and functionally sparing therapy for early endometrial cancer. Tumors of Female Reproductive System. Opukholi zhenskoi reproduktivnoi sistemy. 2007; (1-2): 50-3.(in Russian).]

- Jadoul P., Donnez J. Conservative treatment may be beneficial for young women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial adenocarcinoma. Fertil. Steril. 2003; 80(6): 1315-24. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(03)01183-x.

- Минздрав Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Рак тела матки. Ассоциация онкологов России, Российское общество клинической онкологии; 2018. [Minzdrav Rossiiskoi Federatsii. Klinicheskie rekomendatsii. Rak tela matki. Assotsiatsiya onkologov Rossii, Rossiiskoe obshchestvo klinicheskoi onkologii; 2018. (in Russian).]

- Guillon S., Popescu N., Phelippeau J., Koskas M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors for remission in fertility-sparing management of endometrial atypical hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019; 146(3): 277-88. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12882.

- Rodolakis A., Biliatis I., Morice P., Reed N., Mangler M., Kesic V., Denschlag D. European Society of Gynecological Oncology Task Force for Fertility Preservation: Clinical recommendations for fertility-sparing management in young endometrial cancer patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2015; 25(7): 1258-65.https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/igc.0000000000000493.

- Бохман Я.В. Руководство по онкогинекологии. М.: Медицина; 1989. [Bokhman Ya.V. Guide to oncogynecology. Moscow: Meditsina; 1989.(in Russian).]

- Dumesic D.A., Lobo R.A. Cancer risk and PCOS. Steroids. 2013; 78(8): 782-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2013.04.004.

- Chae S.H., Shim S.H., Lee S.J., Lee J.Y., Kim S.N., Kang S.B. Pregnancy and oncologic outcomes after fertility-sparing management for early stage endometrioid endometrial cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2019; 29(1): 77-85. https:/dx.doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2018-000036.

Received 27.11.2019

Accepted 07.02.2020.

About the Authors

Lana G. Dzhanashvili, Ph.D. Student at the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia. Tel.: +79629185619. E-mail lana.janashvili@gmail.com;https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2891-3974

117997 Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4.

Tatiana A. Nazarenko, Dr.Med.Sci., Professor, Head of the Institute of Reproductive Medicine, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia. Tel.:+7(915)3220879.E-mail:t.nazarenko@mail.ru https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5823-1667 117997 Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4.

Olga S. Balakhontseva, Ph.D. at the Professor Zdanovsky Clinic, Moscow, Kholodilniy str., 2. E-mail: osbal2383@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4813-8442

Yana O. Martirosyan, Clinical Resident at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatology and Reproductive Medicine of the Medical Faculty, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU of Minzdrav of Russia (Sechenov University). Tel.: +7(925)1249999. E-mail marti-yana@index.ru https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9304-4410

117997 Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4.

Elena A. Kalinina, Dr.Med.Sci., Professor, Head of B.V. Leonov Department of Assisted Technologies in Infertility, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow Ac. Oparina Street 4. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8922-2878

Almina M. Biryukova, Ph.D., Clinical Care Supervisor at the F. Paulsen Research and Educational Center for ART with the Clinical Department, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia. 117997 Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4.

Stanislav M. Pronin, Ph.D., Senior Researcher at the Department of Innovative Oncology and Gynecology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of Minzdrav of Russia.

117997, Russia, Moscow Ac. Oparina Street 4. Tel.: 8(495)5314444. E-mail: s_pronin@oparina4.ru

For citation: Dzhanashvili L.G., Nazarenko T.A., Balakhontseva O.S., Martirosyan Ya.O., Pronin S.M., Kalinina E.A., Biryukova A.M. Realization of reproductive potential in patients with atypical hyperplasia and stage I endometrial cancer.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/ Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020; 4: 45-51. (In Russian).

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.4.45-51