Uterine scar dehiscence following caesarean section

Objective: To investigate pregnancy outcomes in patients with uterine scar dehiscence (lower uterine segment thickness ≤1–1.2 mm) and analyze the pathomorphological findings of the dissected scar.Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Barykina O.P., Skryabin N.V., Nigmatullina E.R.

Materials and methods: In this study, a retrospective analysis was conducted of 80 delivery notes of patients with uterine scar dehiscence after the lower uterine segment cesarean section.

Results: A history of one, two, and three cesarean sections had 54/80 (67.5%), 23/80 (28.7%), and 3/80 (3.8%) patients with uterine scars dehiscence, respectively. The indication for elective surgical delivery in 60/80 (75%) was a scar thickness ≤ 1–1.2 mm when evaluated by ultrasound. The onset of uterine contractions was an indication for delivery in 20/80 (25%) patients. At the time of delivery, the gestational age was 38 (38;39) weeks, and the uterine aneurysms were diagnosed at 37 (37;38) weeks. In 16/80 (20%) pregnant women, aneurysms were detected before 37 weeks, with the earliest diagnosis at 21 weeks. Pregnancies resulted in singletons in 79/80 (98.8%) and a twin in 1/80 (1.2%) women. Among singleton pregnant women, 10/79 (12.7%) gave birth to large babies. Histological examination revealed scar thinning to 1 mm, myometrium replacement by connective tissue ≥ 50% in 63/80 (78.8%) patients. Splitting hemorrhages in the scar were found in 33/80 (41.3%).

Conclusion: Post cesarean uterine scar dehiscence detected by ultrasound in asymptomatic pregnant women should be managed conservatively. Prolongation of pregnancy beyond 38–39 weeks is inappropriate because it is associated with a potential increase in fetal weight, a predictor of bleeding in the thinned scar caused by excessive stretching.

Keywords

Despite the WHO statement on optimal cesarean section rate, it reaches 25–30% in many European countries and exceeds 60–70% in Asian and Latin American countries [1]. In 2020, the cesarean delivery rate in the Russian Federation was 30.3% and 26.4% in Moscow [2].

Long-term adverse effects of the cesarean section include scar niche requiring surgical correction; placenta previa in the scarred uterus; the need for a repeat cesarean section; uterine scar defects and, as its extreme manifestation, scar dehiscence or uterine aneurysm in subsequent pregnancies. In 2020, 14.5% of cesarean deliveries at the MD Group Clinical Hospital were performed for uterine scar dehiscence.

When a pregnant woman has a uterine scar after cesarean section, a clear distinction must be made between complete uterine rupture, incomplete uterine rupture, and scar dehiscence. Complete uterine rupture has a striking and specific clinical picture. The main difference between scar dehiscence and an incomplete uterine rupture is the morphological characteristics of the uterine wall. In scar dehiscence, the uterine wall, although extremely thin and represented by a filmy connective tissue structure, often devoid of muscle fibers, retains its integrity. In incomplete uterine rupture, the integrity of the uterine wall is compromised, and only the peritoneum is intact. Incomplete uterine rupture is almost always accompanied by the patient's complaints (nausea, vomiting, pain in the epigastrium, scar area, abdomen, and bloody discharge) and specific clinical symptoms (increased uterine tone, fetal hypoxia, pain or tenderness to palpation in the scar area, and abnormal labor patterns).

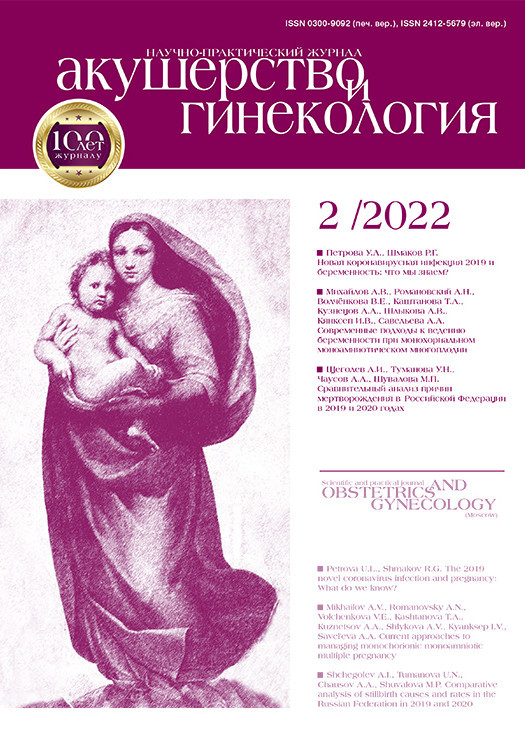

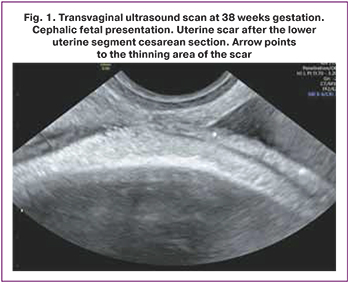

On ultrasound examination in pregnancy, scar dehiscence appears as a bulging of the uterine contour at the lower uterine segment due to thinning of the scar tissue to ≤1–1.2 mm [3]. In Russia, the terms "scar dehiscence" and "uterine aneurysm" are often replaced by 'failing scar,' the ultrasound diagnostic characteristics of which were previously thought to be a lower uterine segment thickness <2.5 mm, multiple echo positive inclusions, and poor vascularization [4]. According to the latest Clinical Guidelines (2021), irregular critical thinning of the uterine scar area with signs of deformity may indicate scar failure [5]. "Critical thinning" is a value judgment, which makes it challenging to use this criterion in practice.

The management of pregnant women with a thinning scar area ≤1–1.2 mm and gestational age <35–37 weeks may not be clear enough for the obstetrician-gynecologist.

This study aimed to investigate pregnancy outcomes in patients with uterine scar dehiscence (lower uterine segment thickness ≤1–1.2 mm) and analyze the pathomorphological findings of the dissected scar.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study was conducted at the MD Group Clinical Hospital, Lapino Clinic, Moscow. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the N.I. Pirogov Russian State Medical University.

The retrospective analysis included 80 delivery notes of patients with uterine scar dehiscence who underwent cesarean section from 2018 to 2021. Inclusion criteria were a history of uterine scar dehiscence after the lower uterine segment cesarean section; thickness of the uterine wall in the scar area ≤1–1.2 mm measured by ultrasound 12–24 h before surgery; metroplasty during the cesarean section with subsequent histological examination of the dissected scar. Exclusion criteria were uterine scar after corporate cesarean section; placenta previa in the scarred uterus; complete and incomplete uterine rupture along the post-cesarean scar. Analysis of delivery notes included obstetric history, time of uterine aneurysm diagnosis, indication for present cesarean section, and infant weight. Histological examination was performed after Hematoxylin-eosin and Van Gieson staining. The scar was evaluated by transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound examination using GE Voluson S8, Voluson E6, Voluson E10.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Jamovi 1.8.4 software. The normality of the distribution was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Quantitative variables showing normal distribution were expressed as means (M) and standard deviation (SD); otherwise, the median (Me) with interquartile range (Q1; Q3) were reported. Categorical variables were summarized using frequency counts and percentages.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 35.1 (4.2) years. A history of one, two, and three cesarean sections had 54/80 (67.5%), 23/80 (28.7%), and 3/80 (3.8%) patients with uterine scars dehiscence, respectively. A history of uterine curettage had 41/80 (51.3%) patients. Ultrasound characteristics of the scar were similar in all patients: on transabdominal and transvaginal scans, the lower uterine segment appeared as a hypoechogenic band with clear even contours, ≤1–1.2 mm thick, without inclusions and blood vessels (Fig. 1, 2). Based on ultrasound findings, 60/80 (75%) and 20/80 (25%) pregnant women underwent elective and emergency delivery, respectively. Emergency delivery was performed in patients with regular labor [14/20 (70%)] and preliminary pains [6/20 (30%)]. At the time of delivery, the gestational age was 38 (38;39) weeks, and the uterine aneurysms were diagnosed at 37 (37;38) weeks. In 16/80 (20%) pregnant women, aneurysms were detected before 37 weeks of gestation [mean 33.5 (4.4) weeks]. The earliest gestational age at the time of uterine aneurysm diagnosis was 21 weeks. Pregnancies resulted in singletons in 79/80 (98.8%) and a twin in 1/80 (1.2%) women. Among singleton pregnant women, 10/79 (12.7%) gave birth to large babies, with a maximum birth weight of 4460 g. Histological examination revealed scar thinning to 1 mm and myometrium replacement by connective tissue ≥ 50% in 63/80 (78.8%) patients. Replacement of myometrium with connective tissue ≥50% was observed in 42/54 (77.8%) patients who had a uterine scar after one cesarean section, in 19/23 (82.6%) after two operations, and in 2/3 (66.7%) after three cesarean sections. Splitting hemorrhages in the scar were found in 33/80 (41.3%).

Discussion

Cesarean scar dehiscence, detected in the late second or early third trimester (after 30–33 weeks), is usually present as an incidental finding during a routine ultrasound examination and is not accompanied by clinical manifestations and complaints of the pregnant woman. The indication for cesarean section is a significant thinning (1–1.2 mm) of the scar area in the lower uterine segment in patients with a history of a cesarean section. Despite reports in the literature of vaginal childbirth after two or even three abdominal deliveries, the clinical guidelines recommend cesarean section in this group of women.

Most of the patients in our study (75%) had a planned delivery at full-term. Emergency delivery related to the development of regular labor or preterm pains was not accompanied by fetal deterioration or a technical complication of the cesarean section, of which metroplasty was an obligatory part.

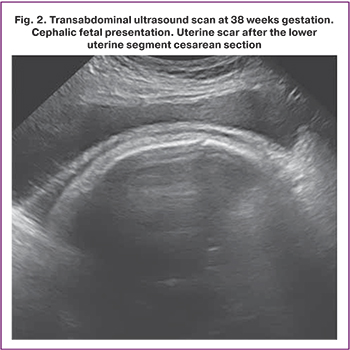

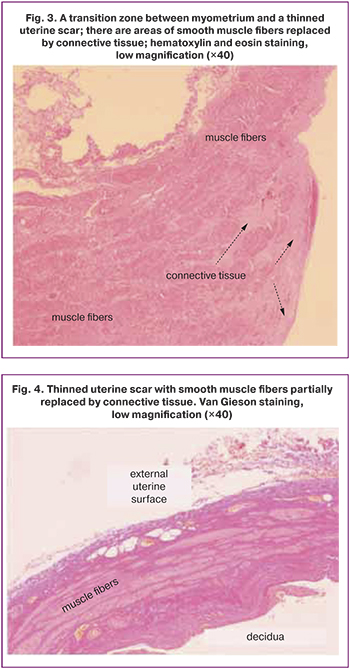

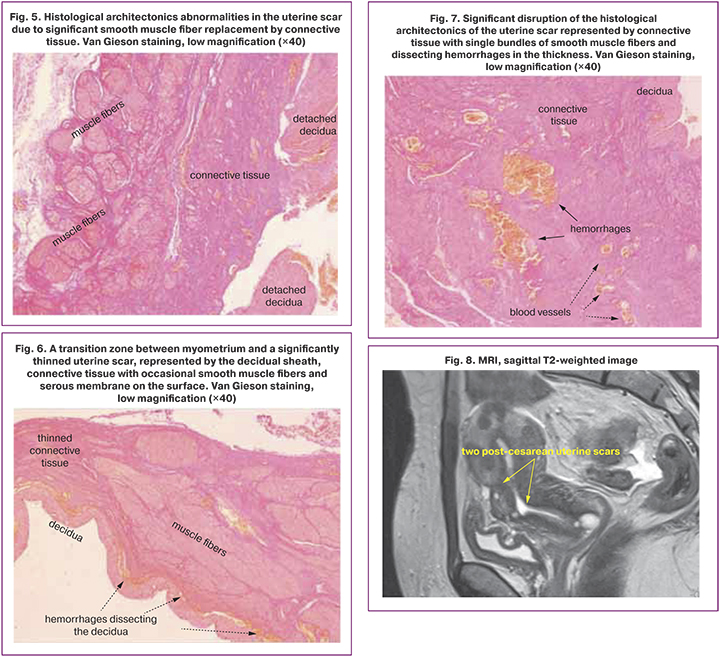

Histological examination of the excised scar allowed us to formulate the main pathomorphological characteristics of the uterine scar dehiscence: 1) significant thinning; 2) replacement of muscle tissue by connective tissue, up to complete disappearance of muscle tissue; 3) appearance of hemorrhages in the scar.

Sometimes there is a transition zone between tissue with normal thickness and structure and an area of myometrial thinning significantly replaced by connective tissue (Fig. 3). In the thinned lower uterine segment, the muscle fibers may remain as isolated scattered fibers (Fig. 4, 5) or disappear entirely (Fig. 6).

We could find no information in the available literature on detecting dissecting hemorrhages in scar dehiscence, although we found them (Fig. 7) in the scar in 41.3% of patients. In contrast to the blood vessels, the hemorrhages are irregularly shaped, have no clearly delineated borders, and lack endovascular endothelial lining (Fig. 7). In our opinion, dissecting hemorrhages should be regarded as an extreme degree of stretching of the scar dehiscence.

Malysheva et al. (2021), in their morphological study of thinned scars dissected during cesarean section, described granulomatous inflammation with foreign inclusions interpreted as suture material debris in 87.8% of patients and myometrial layer architectonics disruption in 94% of patients. The authors defined a thin scar as one that was <3 mm thick measured by ultrasound in the third trimester of pregnancy, combined with a niche [6]. Our findings differ from those of A.A. Malysheva et al., possibly because of the ultrasound inclusion criteria we adopted.

E. Gyokova et al. (2019) pointed out that low cell proliferation was a histological sign of an incompetent scar in patients with myometrium thickness <2.5 mm at ultrasound and anemia. The researchers classified myometrial hyperplasia and hypertrophy, adenomyosis, fibrosis, myofibril disorganization, and inflammatory elements as variants of the pathological healing of the pre-existing scar. Myometrial echographic thickness ranged from 1.73 to 3.79 mm [7].

O. Bӑlӑlӑu et al. (2019) reported that uterine scar dehiscence was found in 34% of patients during Cesarean section. Still, the authors did not correlate this with ultrasound findings in the third trimester, although they illustrated an ultrasound scar thickness of 1.1 mm. Histological examination revealed adenomyosis, inflammatory infiltration, granulation tissue overgrowth, and neovasculogenesis [8].

In asymptomatic pregnant women, the post-cesarean uterine scar dehiscence detected by ultrasound should be managed conservatively [9].

Conclusion

Elective repeat cesarean delivery can be performed with obligatory visualization of the uterine scar dehiscence, dissection of the vesicovaginal fold, dissection, and posterior displacement of the bladder caudally. After exposing the dehiscent area, dissecting the uterus in this area, and removing the fetus, thinned scar should be excised, and uterine wound edges approximate, i.e., metroplasty should be performed. Metroplasty is obligatory for several reasons. Firstly, it prevents hypotonic bleeding in the early postoperative period. A dehiscent scar is an overstretched inferior uterine segment with little or no muscle fiber and cannot contract adequately after birth. Secondly, hysterectomy at different levels of the anterior wall leads to a "shredded uterus" effect (Fig. 8), creating the potential for complications in subsequent pregnancies.

Prolongation of pregnancy beyond 38–39 weeks is inappropriate because it is associated with a potential increase in fetal weight, a predictor of bleeding in the thinned scar caused by excessive stretching.

References

- World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme, 10 April 2015.WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod. Health Matters. 2015; 23(45): 149-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2015.07.007.

- Основные показатели деятельности акушерско-гинекологической службы в Российской Федерации в 2020 году. Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Департамент медицинской помощи детям и службы родовспоможения. М.; 2021. [Key indicators of the obstetric and gynecological service in the Russian Federation in 2020. Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Department of Medical Assistance to Children and Obstetrics Service. Moscow; 2021. (in Russian)].

- Савельева Г.М., Курцер М.А. Бреслав И.Ю., Караганова Е.Я., Неклюдова Ю.Г. Непроникающий разрыв матки по рубцу после кесарева сечения и расползание/аневризма рубца на матке во второй половине беременности и в родах. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 6: 66-72. [Savelyeva G.M., Kurtser M.A. Breslav I.Yu., Karaganova E.Ya., Neklyudova Yu.G. Non-penetrating rupture of the uterus along the scar after cesarean section and creeping/ aneurysm of the scar on the uterus in the second half of pregnancy and childbirth. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 6: 66-72. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.6.66-72.

- Письмо Министерства здравоохранения и социального развития РФ от 24 июня 2011 г. №15-4/10/2-6139 «Кесарево сечение в современном акушерстве». [Letter of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation dated June 24, 2011 No. 15-4 / 10 / 2-6139 "Caesarean section in modern obstetrics". (in Russian)].

- Российское общество акушеров-гинекологов. Клинические рекомендации «Послеоперационный рубец на матке, требующий предоставления медицинской помощи матери во время беременности, родов и в послеродовом периоде». 2021. [Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Clinical guidelines "Postoperative scar on the uterus, requiring the provision of medical care to the mother during pregnancy, childbirth and in the postpartum period". 2021. (in Russian)].

- Малышева А.А., Матухин В.И., Рухляда Н.Н., Тайц А.Н., Новицкая Н.Ю. Факторы риска дефекта рубца на матке после кесарева сечения. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 2: 77-83. [Malysheva A.A., Matukhin V.I., Rukhlyada N.N., Taits A.N., Novitskaya N.Yu. Risk factors for cesarean uterine scar defect. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 2: 77-83 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.2.77-83.

- Gyokova E., Popov Y., Ivanova-Yoncheva Y., Georgiev A., Dimitrova M., Betova T. et al. Clinical-morphological evaluation of the quality of the uterine scar tissue after caesarean section. J. IMAB. 2019; 25(1): 2433-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.5272/jimab.2019251.2433.

- Bӑlӑlӑu O., Bacalbasa N., Bӑlӑlӑu C., Negrei C., Gӑlӑteanu B., Ghinghinӑ O. et al. The correlation between histopathological and ultrasound findings regarding Cesarean section scars – A three-year survey study. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2019; 6(1): 143-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.22543/7674.61.P143149.

- Савельева Г.М., Курцер М.А., Бреслав И.Ю. Разрыв матки. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2021. [Savelyeva G.M., Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu. Uterine rupture. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2021. (in Russian)].

Received 25.11.2021

Accepted 25.01.2022

About the Authors

Mark A. Kurtser, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Academician of the RAS, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pediatric Faculty, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(495)719-78-96, m.kurtser@mcclinics.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0175-1968,117997, Russia, Moscow, Ostrovityanov str., 1.

Irina Yu. Breslav, Dr. Med. Sci., Head of the Department of Pathology of Pregnancy, MD GROUP Clinical Hospital, +7(495)331-44-85, e-mail: irina_breslav@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0245-4968, 111720, Russia, Moscow, Sevastopolsky Ave., 24/1.

Olga P. Barykina, Pathologist, Head of the Department of Anatomic Pathology, MD GROUP Clinical Hospital, +7(495)332-20-22, medslovar@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4943-0741, 111720, Russia, Moscow, Sevastopolsky Ave., 24/1.

Nikolay V. Scriabin, Pathologist at the Department of Anatomic Pathology, MD GROUP Clinical Hospital, +7(495)332-20-22, hranitelkr@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8247-7563, 111720, Russia, Moscow, Sevastopolsky Ave., 24/1.

Elina R. Nigmatullina, Obstetrician-Gynecologist at the MD GROUP Clinical Hospital; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Faculty of General Medicine,

Bashkir State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(960)866-50-50, elinanig@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2006-6210,

111720, Russia, Moscow, Sevastopolsky Ave., 24/1.

Corresponding author: Irina Yu. Breslav, irina_breslav@mail.ru

Authors' contributions: Kurtser M.A. – conception and design of the study; Breslav I.Yu. – conception and design of the study, data analysis, manuscript drafting, and illustrative material preparation; Barykina O.P. – uterine scar dehiscence pathomorphological examination; Skryabin N.V. – uterine scar dehiscence pathomorphological examination, a compilation of photographic materials; Nigmatullina E.R. – review of the relevant literature and delivery notes of patients with uterine scar dehiscence.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the N.I. Pirogov RNRMU,

Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Kurtser M.A., Breslav I.Yu., Barykina O.P., Skryabin N.V., Nigmatullina E.R. Uterine scar dehiscence following caesarean section.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 2: 59-64 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.2.59-64