Psycho-emotional status of patients with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain: relationship analysis and prospects for further research

Levakov S.A., Gromova T.A., Titova N.R., Aslanova M.S., Managadze I.J.

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. This condition can be accompanied by psychosomatic and social discomfort, that requires further research to understand the relationship between different factors influencing its development.

Objective: To explore the spectrum of psychopathological symptoms and syndromes in patients with endometriosis and assess their impact on the development of endometriosis for further determination of possible approaches to treatment in the framework of complex patient-oriented therapy.

Materials and methods: The study included 65 female patients with the diagnosis of endometriosis. Online survey was conducted using Google Forms, which included a set of psychometric tools to assess the levels of anxiety and depression, quality of life, pain catastrophizing in women with chronic pelvic pain (CPP) and its intensity. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and jamovi module for general linear models (GLM).

Results: As a result of the study, 8 general linear models with significance level of p<0.001 with a spectrum of reproductive and mental health indicators were created, and a hypothetical model of relationship between psychoemotional status and CPP in endometriosis was suggested.

Conclusion: The study of the psycho-emotional status of patients with endometriosis found a complex of psychosomatic factors affecting women with this condition. There is a strong relationship between the level of pain, quality of life and women’s mental health, that emphasizes the need for a complex approach to treatment aimed to eliminate psycho-emotional factors and improve the quality of life of patients with endometriosis.

Authors' contributions: Levakov S.A. – developing the concept and design of the study; Managadze I.J. – material collection and processing, article writing, statistical data processing; Aslanova M.S. – article writing, statistical data processing; Gromova T.A., Titova N.P. – article editing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The study was carried out without any sponsorship.

Patient Consent for Publication: The patients have signed informed consent for publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Levakov S.A., Gromova T.A., Titova N.R., Aslanova M.S., Managadze I.J. Psycho-emotional status of patients with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain: relationship analysis and prospects for further research.

Akusherstvo i Gynekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (2): 68-80 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.186

Keywords

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus [1]. Every ninth woman is diagnosed with endometriosis, and most of them have dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain not related to menstruation, asthenia and infertility. Different studies show significant decline in health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis compared with women, who have no this condition. Moreover, a number of epidemiological studies confirmed that women with endometriosis have affective disorders more often than the general population [2]. In addition to somatic symptoms, the patients with endometriosis often experience depression and high anxiety, high levels of perceived stress, as well as different types of pain, that has impact on women’s social life [3]. Due to this, endometriosis should be considered as a systemic disease, but not only as gynecological disease, and it is important to study the psycho-social mechanisms of its development.

Endometriosis can be accompanied by significant psychosomatic and social discomfort, requiring additional research to understand the interdependence of various factors involved in its development. However, it is already clear that in addition to standard treatment, complementary therapies should be used to eliminate pain, as well as psychological and social stress aimed to stop cyclical exacerbation of symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life [4].

Endometriosis is associated with the symptoms of depression, anxiety and self-doubt, leading to a significant reduction in quality of life. Dyspareunia, infertility and decline in the ability to cope with daily life activities in general can create a significant discomfort also in intimate life, reducing relationship satisfaction, and thereby increasing the social burden of endometriosis [5].

Pain catastrophizing is characterized as a tendency of excessive focusing on pain, and magnifies the threat value of pain through cognitive enhancement of pain-related negative thoughts [6].

In recent years, it has become clear that psychological factors, such as pain catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, and pain vigilance are important determinants of pain perception. Chronic pain is associated with worsening health-related quality of life and disrupts many aspects of life of individuals, provoking physical and emotional stress. Changes in health status in endometriosis have the far-reaching consequences, affecting many interrelated aspects, including psychological, physical, social, reproductive, intimate aspects, and, therefore, quality of life in general, significantly worsening patient well-being [7].

A number of epidemiological studies have confirmed that affective disorders are more common in women with endometriosis than in the general population. A review of psycho-emotional disorders experienced by women with endometriosis showed that the prevalence of depression is 86%, moderate and severe anxiety is 29%, and mood disorders reach 68%, that is significantly higher than the prevalence of these disorders in the general population [8].

In recent years, the scientific literature on this issue is gradually emphasizing the importance of assessment of quality of life of women with endometriosis. The symptoms of endometriosis can cause a progressive decline in the ability of women to perform daily life activities, and consequently, deterioration in the perceived health status and overall sense of well-being. The impact of these symptoms on patients’ quality of life has not been studied fully, and therefore, requires further clinical research, fundamental analysis and review of the psychological and social consequences of the disease and the impact of different treatment options on patients’ quality of life and overall well-being [9].

The purpose of the study was to explore the spectrum of psychopathological symptoms and syndromes in patients with endometriosis and assess their impact on the development of endometriosis for further determination of possible approaches to treatment in the framework of complex patient-centered therapy.

Materials and methods

Sampling

The patients with previously surgically and histologically diagnosed endometriosis (No. 90, ICD-10) were enrolled in the study at the Center of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain of Clinical Hospital No. 85 of FMBA of Russia. The patients have signed informed consent to participate in the study. To ensure representative, convenience sampling method (random sampling) was used: all patients of the clinic were invited to participate in the study, and this was made possible due the accessibility of this medical facility, since one of the authors of the study is an employee at this clinic. This method simplified the process of recruiting study participants and ensured that the sample was similar to the structure of the general population of patients with endometriosis, by selecting among all patients at the clinic.

The age of respondents was 20–60 years. Number of respondents in each age group was the following; aged 20–30 years – 6/65 (9.2%), 30–40 years – 21/65 (32.3%), 40–50 years – 24/65 (36.9%), over 50 years – 14/65 (21.5%). Number of respondents, who received hormone therapy was 10/65 (15.4%), and 35.65 (53,8%) received combination treatment with subsequent using both therapeutic methods. The patients with severe concomitant diseases, such as decompensated heart failure, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, stage 3 and other stages of disease progression, decompensated diabetes mellitus, as well as patients with mental disorders were excluded from the study. The patients who refused to participate in the study or could not give informed consent were also excluded from the study.

The study participants completed the online survey using Google Forms, that included author's questions to assess gynecological, gastrointestinal, urinary and general symptoms. Also, standardized methods were used as screening tools aimed at preliminary evaluation of the prevalence and severity of psycho-emotional disorders in patients with endometriosis: the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) to evaluate anxiety and depression, the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the EHP-30 and EQ-5D questionnaires to assess health-related quality of life, visual analogue scale (VAS) to measure the intensity of chronic pelvic pain, and Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) to assess pain catastrophizing.

Research procedure

This cross-sectional observational study analyzed data at a single point in time from the population of women with endometriosis. The patients with previously diagnosed endometriosis, who were admitted to the Center of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain of Clinical Hospital No. 85 of FMBA of Russia, were offered to participate in the study on evaluation of their phychosomatic status. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see “Material and methods”), in September 2023, 65 women were selected for the study. After signing voluntary informed consent, clinical interview, examination, laboratory and instrumental examinations were conducted, and the patients were asked to complete online questionnaires using Google Forms (within 15–20 minutes).

The severity of endometriosis, invasion severity and prevalence of endometrial heterotopias, intensity of pain syndrome undoubtedly reduce woman’s quality of life and her ability for full self-realization – career growth, social participation, maintenance of active social connection, fulfilling social role, that can become a trigger for the development of psycho-emotional disorders and deterioration of the psycho-emotional status in general, and also increase the susceptibility of patients to the social micro environment factors. Therefore, the approach to explore this problem is based on a biopsychosocial model, where the basis of the biological link is a morphological substrate of endometriosis – endometrial heterotopias outside the uterine cavity, the presence of which is confirmed by the results of gynecologic diagnostic tests; and the basis of the social link including the social micro environment, support or stigmatization of patients with endometriosis, and the psychological component represents a wide range of psycho-emotional disorders.

Methods

The following combined psychometric methods, questionnaires and scales were used to assess psycho-emotional status, quality of life and intensity of chronic pelvic pain in patients with endometriosis:

1) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for the diagnosis of clinically significant anxiety and depression in ambulatory patients and for differential diagnosis between anxiety and depression.

For each of these conditions 7 questions were asked to assess the severity of anxiety and depression. Each question has 4 answer options estimated (from 0 to 3 –point estimate). Maximum of measured points is 21 for each disorder. The results are interpreted as normal (the score of 0–7), subclinical (the score of 8–10) and clinical severity of anxiety and depression (the score above 11) [10, 11].

2) The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) – a clinical tool used to quantify the severity of anxiety disorders in patients and the dynamics of this condition in the process of treatment.

The scale consists of 14 items, 13 of them refer to anxiety in everyday life, and item 14 refers to anxiety during medical examination. Each item is assessed by respondents using the 0–4 point scale (0 – absence of anxiety, 4 – severe anxiety). To calculate the total score reflecting the severity of anxiety disorder, it is necessary to sum up the points of all items. The score of 17 points or less indicate the absence of anxiety, 18–24 points indicate moderate severity of anxiety disorder, 25 points or higher indicate severe anxiety [12, 13].

3) the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) – is a clinical tool for preliminary assessment, and a rating scale of anxiety disorders in a wide range of people – young people aged 14 years and over, mature and older adults, clinical patients and in screening studies.

This self-report questionnaire consists of 21 items. Each item includes one of the typical anxiety symptoms – physical or mental symptoms. Each item is assessed by the respondent using the 0–3 point scale (0 – no symptom bother, 3 – severe symptom bother). The score is calculated by summing up the points for all items of the BAI. The score ≤21 indicate mild anxiety, the score 22–35 indicate moderate anxiety, the score ≤36 (with a maximum of 63) indicate severe anxiety [13, 14].

Duplicate questionnaires were used to improve the quality of interpretation of psycho-emotional status assessment results and personalize the approach to its diagnosis. Each questionnaire has own characteristics, and using a combination of several tools made it possible to take into account different aspects of anxiety. Although the HADS, HAM-A and BAI are aimed at anxiety assessment, these tools are focused on its various manifestations. The HADS assesses anxiety and depression as separate constructs; the HAM-A is more focused on assessment of somatic manifestations, and the BAI is focused on subjective sensations and bodily manifestations caused by anxiety and experienced at the moment. Thus, after interpretation of the results, we could obtain groups with different composition, indicating both the severity of anxiety in general, and the leading component – psychological or somatic, in particular, that could not be identified without using several questionnaires covering different aspects of anxiety.

4) The Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30) questionnaire is a reliable, accurate, patient-centered tool for assessment of quality of life in endometriosis. The core part of the questionnaire consists of six scales assessing pain, control, vitality, emotional component, social support and self-esteem, and is suitable for all women with endometriosis. Each item is scored on the scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Quality of life of women with endometriosis is assessed both within each individual subscale and by summing the scores of all six scales of the basic block into a total scale (ranging from the best possible health status to the worst) [15, 16].

5) European Quality of Life Questionnaire (EQ-5D) is a generic tool which is used to evaluate respondent’s health-related quality of life. It helps to create an individual's unique health profile incorporating five questions (mobility, self-care, daily life activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression). Each question has three choices for the answer about the degree of the severity of the problem (the absence of problem, insignificant problem and significant problem) [17–19].

6) Visual analogue scale (VAS) is used to measure pain intensity ranging from 0 to 10 along the horizontal line of the pain scale (0 – no pain, 5 – moderate pain and 10 – worst pain imaginable) [20, 21].

7) Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) allows to assess in the express mode the degree of involvement of emotional and behavioral components in the structure of pain syndrome. Pain catastrophizing is defined as a psychopathological process, which is characterized by "maladaptive, negative assessment of certain symptoms and increased attention to them" and reflects the tendency of patients to overfocus on pain, magnifying the threat value of pain up to health threatening state through cognitive reinforcement of negative thoughts.

The traditional method of using the PCS offers the participants to reflect on their past pain experience and indicate the degree to which they had each of 13 thoughts or feelings when they experienced pain on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). The PCS provides a total score and the scores for 3 subscales to measure rumination, magnification, and helplessness.

Pain Catastrophizing Scale includes three approaches to explain this phenomenon, that is reflected in three different scales, which together form a unified indicator of catastrophizing.

- The first approach emphasizes the individual’s focusing on pain-related thoughts and serves as the basis for the first scaling technique – rumination.

- The second approach emphasizes the tendency of some people to exaggerate the threat value, meaning and consequences of pain sensations and serves as the basis for identifying the second scaling technique – magnification.

- The third approach emphasizes the acceptance of being humble, helplessness and inability to cope with the situation when experiencing pain and serves as the basis for the third scaling technique – helplessness.

These three scales are moderately interrelated, that makes it possible to consider them as different components of one core construct. The final pain catastrophizing score is obtained by adding up the scores of all three scales [22, 23].

Along with the standardized scales, the study used a specially developed author's questionnaire aimed at describing the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and a wide range of symptoms, including gynecological, gastrointestinal, urinary and general manifestations, which served as criteria for inclusion in the sample.

As a result of data analysis obtained using the scales for affective disorders, quality of life and pain intensity, the respondents were divided into groups with low (n=35), moderate (n=20) and high (n=10) scores. Distribution of norm values was determined according to the standardized norms of the psychometric tests. Differentiation of the respondents was done by the expert group consisting of the authors of this article and two doctors at the Center of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain of Clinical Hospital No. 85 of FMBA of Russia, that facilitates the interpretation quality of the results. To confirm the reliability of differentiation, the Kendall's coefficient of concordance was calculated, which showed a high degree of agreement between the assessments (W=0.728).

Statistical analysis

The following parameters of descriptive statistics were used to describe and characterize the sample: the quantitative variables (for example, scale scores) are represented as arithmetic mean (M), standard deviation (SD) and median (Me). The categorical variables (for example, the type of therapy, age groups) are represented as absolute (n) and relative frequency data (%). A number of statistical methods aimed at exploring the relationship between psycho-emotional status, clinical manifestations of endometriosis and patients’ quality of life were used to analyze the obtained data. All statistical calculations were performed using Jamovi software, version 2.3.16. The level of statistical significance was at p<0.05 for all tests (with 95% confidence interval).

Distribution of values for all quantitative rating scales in the study was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Test results showed that distribution in the sample was significantly different from normal (p<0.001). Due to this, Z-standardization of all metric scales was performed for further analysis using parametric methods (such as the General Linear Models with fixed effects, Fisher's exact test to assess significance of factors, and the Games-Howell post-hoc test to compare the groups with unequal variances). However, for interpretation of the results and representation of descriptive statistics, comparisons between the groups were based on the arithmetic mean of the initial (non-standardized) scales.

At the first stage, the Student's t-test was used to assess the differences in psychometric parameters between the patients of different age groups and types of therapy. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups (p>0.05), that allowed to exclude these factors from further analysis as covariates.

General Linear Models (GLMs) were used to assess the effects of factors on dependent variables, such as anxiety, depression, pain, and quality of life. Effect sizes in the models were estimated by partial eta-squared (η²p). The Games–Howell post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons, as it assumes unequal variances.

Results

Descriptive statistics

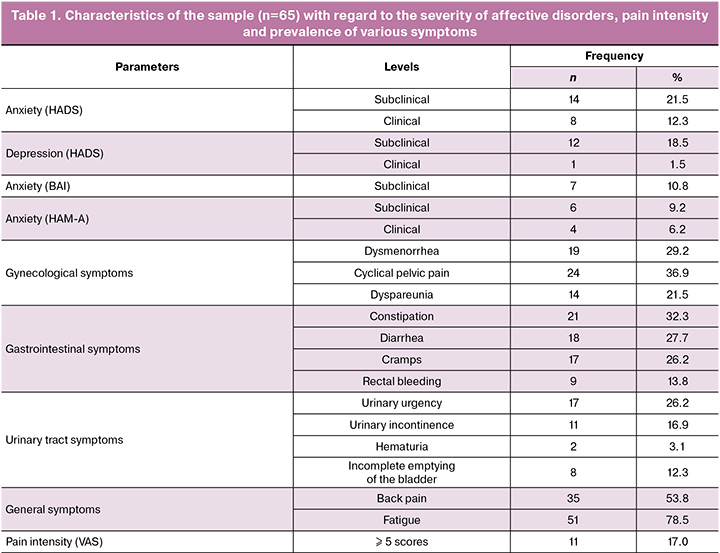

The data describing the sample with regard to the severity of affective disorders, pain intensity and prevalence of various symptoms are represented in Table 1. Absolute and relative frequencies are shown for different levels obtained on the basis of standardized norms, psychometric methods, as well as the frequency of occurrence of gynecological, gastrointestinal and urinary tract symptoms. For more detail see section “Methods”.

The above gynecological, gastrointestinal, urinary tract and general symptoms belong to a wide spectrum of symptoms observed in patients with endometriosis.

Pain is a common symptom experienced by women with endometriosis. Chronic pelvic pain, including dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, non-menstrual non-cyclic pain, lasts for at least six months, and it is severe enough to interfere with daily life activities. The pathophysiological mechanisms of CPP are associated with deposition of ectopic endometrial fragments, inducing the release of proinflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, chemokines and other substances from endometriotic foci during chronic inflammation. In addition, deep infiltration causing tissue damage, adhesion formation, fibrous thickening and accumulation of menstrual blood in endometriotic implants leads to painful stretching. These changes can stimulate the release of growth factors that induce the growth in the number of nerve fibers in endometriotic lesions, increasing pain. Women with chronic pelvic pain have neurological changes in the posterior horn of the spinal cord, that leads to neurogenic inflammation in the pelvic area, hyperalgesia, dysreflexia, reduced sensitivity threshold and, as a result, increased pain sensations [24].

Impaired pain processing, dysautonomia autonomic dysfunction, and neuromuscular disorders cause gastrointestinal symptoms, including cramps and neurogenic intestinal motility disorders [25]. In turn, urinary disorders observed in endometriosis (daytime pollakiuria and nighttime nocturia, or imperative urinary incontinence, spontaneous and stress urinary incontinence, frequent urination, cystalgia, dysuria, urinary retention, cramps or pain during or after urination, reduced bladder sensation, low back pain) indicate endometriotic foci infiltrating the hypogastric plexus in combination with inflammatory phenomena and excessive expression of growth factors in nerve tissue [26].

In connection with the above, it seems relevant to explore the relationship between somatic manifestations of endometriosis and the psycho-emotional status of patients.

Preliminary analysis assessed the statistical differences between the groups of patients depending on their age (the groups of reproductive and older age) and the type of therapy (hormone therapy and surgery) based on the results of psychometric tests. Analysis (the Student’s t-test, p<0.05) showed no statistically significant differences between the groups.

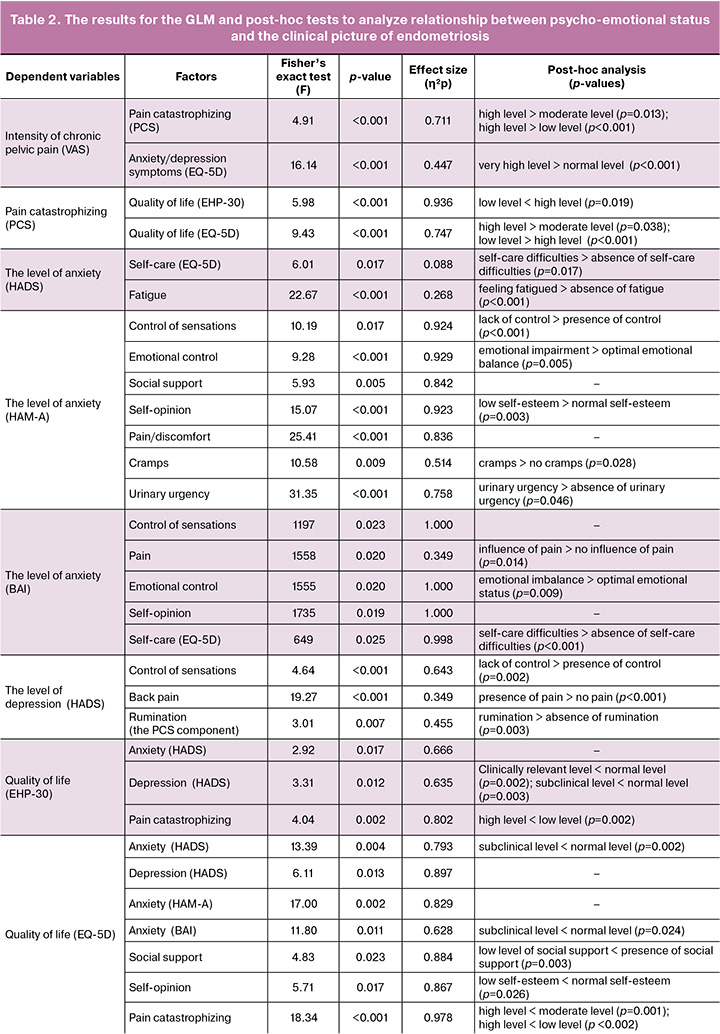

A series of general linear models (GLMs) was built to analyze the relationship between psycho-emotional status and chronic pelvic pain in endometriosis (Table 2). As a result of using GLM with assessment of the intensity of chronic pelvic pain as a dependent variable using the VAS, two statistically significant factors (Fisher’s exact test F=6.8, p<0.001, η²p=0.789) were identified: the level of pain catastrophizing (PCS) (F=4.91, p<0.001, η²p=0.711) and the presence of anxiety and/or depression symptoms in respondents (the EQ-5D questionnaire) (F=16.14, p<0.001, η²p=0.447). Post-hoc analysis (the Games-Howell test assuming unequal variances) showed that the intensity of chronic pelvic pain was significantly higher in patients with a high level of catastrophizing, compared with a moderate (the Games–Howell test, p=0.013) and low levels (p<0.001). Also, in respondents with high levels of anxiety and/or depression (the EQ-5D), intensity of chronic pelvic pain was significantly higher (p<0.001).

In the general linear model (GLM) with the level of pain catastrophizing as a dependent variable, two statistically significant factors (Fisher’s exact test, F=13.32, p<0.001, η²p=0.975) were identified: quality of life using the EHP-30 scale (F=5.98, p<0.001, η²p=0.936), and quality of life using the EQ-5D questionnaire (F=9.43, p<0.001, η²p=0.747). Post-hoc analysis (the Games-Howell test) showed that the level of pain catastrophizing was significantly higher in patients with low quality of life according to the EHP-30 scale compared with high quality of life (p=0.019). Also, in respondents with low quality of life measured using the EQ-5D questionnaire, the level of catastrophizing was significantly higher compared with moderate (p=0.038) and high (p<0.001) levels.

In the general linear model (GLM) with assessment of the level of anxiety as a dependent variable using the HADS (Fishers’ exact test F=16.20, p<0.001, η²p=0.343), two statistically significant factors were identified: self-care – the descriptive system component of the EQ-5D (F=6.01, p=0.017, η²p=0.88) and fatigue (F=22.67, p<0.001, η²p=0.268). Post-hoc analysis (the Games–Howell test) showed that the level of anxiety measured using the HADS was significantly higher in the respondents feeling fatigued compared with the respondents without fatigue (p<0.001). Also, in patients who had self-care difficulties, the level of anxiety was significantly higher compared with the patients without these difficulties (p=0.017).

In the general linear model (GLM) with assessment of the level of anxiety as a dependent variable using the Hamilton anxiety rating scale (HAM-A) (Fisher’s exact test, F=13.66, p<0.001, η²p=0.987), seven statistically significant factors were identified: control of sensations (F=10.19, p=0.017, η²p=0.924), control of emotions (F=9.28, p<0.001, η²p=0.929), social support (F=5.93, p=0.005, η²p=0.842), self-opinion (F=15.07, p<0.001, η²p=0.923), pain/discomfort (F=25.41, p<0.001, η²p=0.836), cramps (F=10.58, p=0.009, η²p=0.514), and urinary urgency (F=31.35, p<0.001, η²p=0.758). Post-hoc analysis (the Games–Howell test) showed that the level of anxiety according to the HAM-A was significantly higher in patients with lack of control of perceived symptoms compared with the respondents, who were able to control their sensations (p<0.001); with emotional impairment compared with the patients with optimal emotional balance (p=0.005); with low self-esteem compared with normal self-esteem (p=0.003), as well as in the presence of the symptoms, such as abdominal cramps, painful bowel movements (p=0.028) and urinary urgency (p=0.046) compared with absence of these symptoms.

In the general linear model (GLM) with assessment of the level of anxiety as a dependent variable using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Fisher’s exact test F=2983, p=0.015, η²p=1.000), five statistically significant factors were identified: control of sensations (F=1197, p=0.023, η²p=1.000), pain (F=1558, p=0.020, η²p=0.349), emotional control (F=1555, p=0,020, η²p=1,000), self-opinion (F=1735, p=0.019, η²p=1.000), and self-care – a component of the descriptive system component of the EQ-5D (F=649, p=0.025, η²p=0.998). Post-hoc analysis (the Games–Howell test) showed that the level of anxiety according to BAI was significantly higher in patients, whose sensations of pain negatively influenced physical and social activities compared with the respondents who did not experience discomfort (p=0.014), in patients with emotional imbalance compared with the patients with optimal emotional status (p=0.009), and in the presence of self-care difficulties compared with their absence (p<0.001).

In the general linear model (GLM) with assessment of depression as a dependent variable using the HADS (Fisher’s exact test F=5.17, p<0.001, η²p=0.789), three statistically significant factors were identified: control of sensations (F=4.64, p<0.001, η²p=0.643), back pain (F=19.27, p<0.001, η²p=0.349) and rumination – the component of pain catastrophizing (F=3.01, p=0.007, η²p=0.455). Post-hoc analysis (the Games–Howell test) showed that the level of depression measured using the HADS was significantly higher in the patient who were unable to control their physical symptoms compared with the respondents who were able to control their sensations (p=0.002); in the presence of back pain compared with its absence (p<0.001), as well as in patients who focus on negative thoughts related to pain (rumination) compared to those, who have no this component of pain catastrophizing (p=0.003).

In the general linear model (GLM) with assessment of quality of life as a dependent variable using the EHP-30 (Fisher’s exact test, F=7.79, p<0.001, η²p=0.946), three statistically significant factors were identified: the level of anxiety according to the HADS (F=3.31, p=0.012, η²p=0.635) and the level of pain catastrophizing (F=4.04, p=0.002, η²p=0.802). Post-hoc analysis (the Games–Howell test) showed that the level of quality of life assessed using the EHP-30 was significantly lower in patients with clinical (p=0.002) and subclinical (p=0.003) levels of depression, compared with normal level, as well as with high level of pain catastrophizing compared with low level (p=0.002).

In the general linear model (GLM) with assessment of quality of life as a dependent variable using the EQ-5D scale (Fisher’s exact test, F=27.94, p<0.001, η²p=0.995), seven statistically significant factors were identified: the level of anxiety (the HADS) (F=13.39, p=0.004, η²p=0.793), the level of depression (the HADS) (F=6.11, p=0.013, η²p=0.897), the level of anxiety (the HAM-A scale) (F=17.00, p=0.002, η²p=0.829), the level of anxiety (the BAI (F=11.80, p=0.011, η²p=0.628), social support (F=4.83, p=0.023, η²p=0.884), self-opinion (F=5.71, p=0.017, η²p=0.867), and the level of pain catastrophizing (F=18.34, p<0.001, η²p=0.978). Post-hoc analysis (the Games–Howell test) showed that quality of life assessed using the EQ-5D was significantly lower in patients with subclinical level of anxiety according to the HADS (p=0.002) and the BAI (p=0024) compared to normal level. Also, lower quality of life was in the respondents, who felt lonely and misunderstood by the society compared with the respondents, who felt social support (p=0.003); in the respondents with low self-esteem compared with normal self-esteem (p=0.026), and with high level of pain catastrophizing compared with moderate (p=0.001) and low (p<0.002) levels.

Thus, based on analysis of the general linear statistical models (GLMs) and post-hoc tests, it was found that psycho-emotional factors in combination with clinical manifestation have a significant impact on quality of life of patients with endometriosis.

Severe chronic pelvic pain is associated with a high level of pain catastrophizing, as well as with the presence of anxiety and depressive symptoms.

- Increased pain catastrophizing is associated with low quality of life, which in turn is due to various psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, as well as impaired social interaction (low social support) and negative self-esteem.

- At symptom level, lack of control of sensations, the presence of back pain, pronounced rumination, fatigue and self-care difficulties are also closely associated with increased levels of anxiety and depression.

- In addition, the presence of symptoms, such as cramps and urinary urgency are associated with increased level of anxiety.

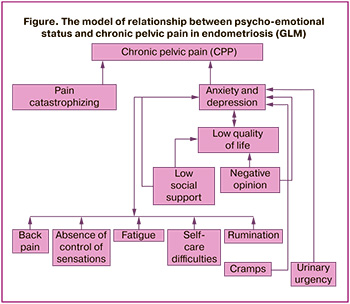

Theory-based analysis of general linear statistical models suggests a possible relationship structure between the psycho-emotional status and the clinical picture of endometriosis (Figure).

This diagram clearly demonstrates that distortions of self-perception and social stigmatization in women with endometriosis form a pattern of anxiety-depressive symptoms, that reduces quality of life, increases maladaptive pain cognitions and, ultimately, the intensity of chronic pelvic pain. Thus, the impact on chronic pelvic pain should be started with the symptoms represented in the bottom of the above associative structure – cognitive restructuring of negative thinking patterns, that will reduce the level of affective disorders, improve quality of life, neutralize extreme pain sensations and, as a result, will lead to improvement of psychosomatic status in general, and reduction in chronic pelvic pain intensity in particular.

It is of special interest that neither the age of patients nor the type of therapy had a significant impact on their psycho-emotional status at the time of the study, that, in turn, suggests that the results obtained by us, not being conditioned by the influence of the above-mentioned factors, represent a universal characteristic of the psychosomatic status of the group of women of a wide range of ages and spectrum of therapeutic approaches in diagnosis of endometriosis.

Discussion

Evaluation of the quality of life and psycho-emotional status of women with endometriosis is becoming an increasingly relevant topic of scientific research. The study by Lisovskaya E.V. et al. assessed various components of quality of life of patients with endometriosis, taking into account both localization and size of endometriotic foci, as well as the presence of infertility and surgical interventions in history, and confirmed a significant relationship between this pathology and all indicators of quality of life of women, that is reflected in our study, and emphasized the advisability of supplementing standard approaches with psychotherapeutic treatment [27].

Similar to our study, the study by Begovich E. et al. assessed pain syndrome and psycho-emotional status of patients with external genital endometriosis using the VAS, the EHP-30, and the HAD. It was found that in women with active rehabilitation approach (information support, psychotherapy with an individual and group approach, climatotherapy, and landscape therapy, etc.), reduction in pain syndrome, improvement of level of emotional, social and sexual activity, reduction in the levels of depression and anxiety were observed compared with patients who underwent a set of rehabilitation measures within the framework of the National Clinical Guidelines. These data confirm our hypothesis about the advisability of supplementing standard approaches to treatment of endometriosis with a set of psychotherapeutic interventions [28].

According to the study by Lerman S.F. et al., depression and anxiety symptoms in women with chronic pelvic pain predict the severity of pain sensations in a long-term perspective, while clinically significant reduction in the levels of depression, anxiety, and pain catastrophizing leads to mild or moderate reductions in pain intensity within one year. This suggests that maladaptive pain cognitions and increased distress may influence pain-related outcomes over time, and reducing these factors may improve women's quality of life. This information is also reflected in the model of relationships proposed by us, in which one of the key links is the severity of affective disorders, that has impact on the intensity of chronic pelvic pain [29].

The novelty in our study lies in covering most of the biopsychosocial factors that determine the psychosomatic status and reproductive health of women with endometriosis. A diverse range of psychometric measurement data on the levels of anxiety, depression, pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and quality of life were evaluated. A wide range of issues related to women’s health characteristics during this difficult period of life were considered. A representative sample of patients was selected at the Center of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain of Clinical Hospital No. 85 of FMBA of Russia. The study helps to better understand both the psycho-emotional aspects and their impact on the somatic status of patients with endometriosis, that remains one of the most acute issues of modern gynecology.

Further research should be aimed at identifying key links in new complex patient-centered psychotherapeutic approaches that help reduce psychological burden and, therefore, improve the quality of life of women with endometriosis, with giving special attention to the relevant socio-cultural contexts – social support, reducing stigma in reproductive health, that will improve the effectiveness of treatment.

Due to a high prevalence of this disease in general, and its psycho-emotional manifestations in particular, we consider it appropriate to recommend screening for psychosomatic status of women diagnosed with endometriosis, as well as a complex of measures to raise awareness of patients and provide information about the prevalence of mental disorders among this cohort of women, and the factors that determine their development.

In our opinion, the identified problems could be solved by expanding the range of healthcare services for patients with endometriosis. Thus, statistically significant results obtained in our original study suggest that the use of psycho-emotional interventions is relevant, has the potential for implementation in clinical practice, and can demonstrate effectiveness in this population group. In this case, it would be possible to propose inclusion of the following modern techniques, which, according to world literature, have proven their effectiveness, in a set of standard recommendations for treatment of this pathology:

- The programs and intervention techniques aimed at reducing stress, based on mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy

Psychological support is important and should be provided in treatment of women with endometriosis [30]. Given the integrative approach based on psychological and physical interventions, it is recommended to conduct a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment taking into account the diverse symptoms of endometriosis. The following body-based and psychological intervention techniques can be considered as possible pain management strategies: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). These intervention techniques can affect pain by changing pain-associated cognitive-affective factors and improve quality of life through several pathways, including but not limited to pain reduction, that emphasizes the potential to improve the affective state for mental health recovery in endometriosis. Compared with other active treatment techniques, these patient-centered methods of psychological intervention can improve not only such aspect of endometriosis as pain, significantly influencing reduction in disability and pain coping, but also negative thinking patterns (that is pain catastrophizing) and physical functioning, and should be considered as a component of complex therapy in women with emotional distress [31].

Therefore, psychological interventions can significantly contribute to conventional therapies for endometriosis with purpose of improvement of psycho-emotional and functional results in all stages of the disease course.

- Application of mobile health (mHealth) technologies with a wide range of patient-centered content

In today’s digital world, the use of endometriosis-specific mHealth interventions, such as regular patient-centered text messaging interventions, can improve the aspects of psychological well-being, such as quality of life, patient empowerment, perceived support, and self-efficacy on adherence to treatment of chronic diseases. These programs provide information about such a common condition as endometriosis, and psychological support to patients using cognitive-behavioral techniques aimed at improving quality of life and mental health of women, and are of particular importance in terms of this serious social issue. Such interventions are highly relevant for this population group and contribute to the potential improvement of psycho-emotional status, including the aspects of quality of life, the problem of loneliness, stress, and psychological distress [32].

- Integrative psychosocial approach based on social support, novelty and the use of open spaces (environmental enrichment)

Environmental enrichment refers to psychosocial intervention that consists of a combination of social and cognitive stimuli (social support, novelty, and exposure to open spaces). Based on the environmental enrichment paradigm, this multi-level integrative intervention would fill the existing gaps in endometriosis treatment strategies [33]. It is possible to use this integrative, patient-centered methodology to develop psychosocial intervention consisting of the activities that mimic and integrate three features of environmental enrichment: social support, novelty, and open spaces, and have been shown to be effective in chronic pain: yoga, yogic breath, mindfulness, aromatherapy, art therapy, music and drama therapy, support groups, and outdoor walks [34].

- Immersive digital therapeutic techniques using virtual reality (VR Endocare)

Over the past few decades, the emergence of digital therapeutics (DTx) aimed at using information tools to support the diagnostic process and treatment of different pathologies, has led to development of many new therapeutic devices (for example, virtual reality (VR) for some types of acute and chronic pain). Special attention is given to the new digital therapeutic approach – Endocare, that combines different therapeutic procedures based on several modalities in the VR environment. Each of them is aimed at reducing pain intensity. The Endocare therapeutic complex includes auditory (e.g. binaural beats in the alpha and theta frequency, nature sounds) and visual (for example bilateral alternative stimulation) components associated with the 3D VR environment, that contributes to a significant reduction in pain intensity in patients with chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis [35].

The main principles of the activities of medical facilities providing treatment and care for patients with endometriosis are accessibility, effectiveness and trust. This is a comprehensive approach that includes a combination of all forms of reproductive health education and the activities of reproductive health services, regular consultations with a gynecologist, medical psychologist, as well as collection and statistical analysis of the obtained data on mental and reproductive health of women with endometriosis with purpose of continuous exploration of the dynamics of effectiveness of the developed measures that contribute to ensuring accessibility and improving the quality of healthcare to restore the psycho-emotional status and reproductive health of patients.

Our study emphasizes the need for longitudinal studies and additional information on the psychosomatic status of women with endometriosis throughout Russia. In our opinion, this study has several strengths. It has minimal publication bias. The results obtained by us serve to raise awareness about psycho-emotional disorders in women with endometriosis and their impact on the intensity of chronic pelvic pain. This problem remains unsolved and should stimulate the initiatives at medical centers and healthcare facilities worldwide.

The limitation of our study is a remote format of the study, and does not allows us to be absolutely sure that our questionnaires were filled out properly. The present study is at the initial stage of exploring the psycho-emotional status of patients with endometriosis and will serve as the basis for a large-scale study of immersive digital virtual reality technologies in terms of psychosomatic aspects of endometriosis at the Center of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain of Clinical Hospital No. 85, the Federal Medical-Biological Agency (FMBA) of Russia.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a complex gynecological disease. Psychological factors of emotional distress and cognition play an important role in understanding and treating endometriosis. However, the temporal relationship with the key pain variables has not been studied fully.

This study encompasses a wide range of psychopathological symptoms and syndromes, and proposes a structure of associative relationships between the level of pain, quality of life, and mental health of women, and emphasizes the need for a comprehensive approach to treatment that includes not only medication therapies, but also psychosocial support aimed at eliminating psycho-emotional factors and improving patients’ quality of life.

References

- Johnson N.P., Hummelshoj L., Adamson G.D., Keckstein J., Taylor H.S., Abrao M.S. et al.; World Endometriosis Society Sao Paulo Consortium. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2017; 32(2): 315-24. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew293.

- Pope C.J., Sharma V., Sharma S., Mazmanian D. A systematic review of the association between psychiatric disturbances and endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2015; 37(11): 1006-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30050-0.

- Ferreira A.L.L., Bessa M.M.M., Drezett J., de Abreu L.C. Quality of life of the woman carrier of endometriosis: systematized review. Reprod. Clim. 2016; 31(1): 48-54. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.recli.2015.12.002.

- van Stein K., Schubert K., Ditzen B., Weise C. Understanding psychological symptoms of endometriosis from a research domain criteria perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2023; 12(12): 4056. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124056.

- Schubert K., Lohse J., Kalder M., Ziller V., Weise C. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for improving health-related quality of life in patients with endometriosis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2022; 23(1): 300. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06204-0.

- Ledermann K., von Känel R., Wagner J. A psychosomatic perspective on endometriosis – a mini review. Cortica. 2023; 2(1): 197-214. https://dx.doi.org/10.26034/cortica.2023.3778.

- Vitale S.G., Petrosino B., La Rosa V.L., Rapisarda A.M., Lagana A.S. A systematic review of the association between psychiatric disturbances and endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2016; 38(12): 1079-80. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2016.09.008.

- Saccone G., Khalifeh A., Elimian A., Bahrami E., Chaman-Ara K., Bahrami M.A. et al. Vaginal progesterone vs intramuscular 17alphahydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth in singleton gestations: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017; 49(3): 315-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.17245.

- La Rosa V.L., Commodari E., Vitale S.G. Psychological considerations in endometriosis. In: Oral E., ed. Endometriosis and adenomyosis: Global perspectives across the lifespan. 2022: 309-28. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97236-3_25.

- Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983; 67(6): 361-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

- Морозова М.А., Потанин С.С., Бениашвили А.Г., Бурминский Д.С., Лепилкина Т.А., Рупчев Г.Е., Кибитов А.А. Валидация русскоязычной версии Госпитальной шкалы тревоги и депрессии в общей популяции. Профилактическая медицина. 2023; 26(4): 7-14. [Morozova M.A., Potanin S.S., Beniashvili A.G., Burminsky D.S., Lepilkina T.A., Rupchev G.E., Kibitov A.A. Validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Russian-language version in the general population. Russian Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2023; 26(4): 7 14. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/profmed2023260417.

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1959; 32(1): 50-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x.

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Генерализованное тревожное расстройство. M.; 2024. 121 с. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Generalized anxiety disorder. Moscow; 2024. 121 p. (in Russian)].

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio: Hacourt Brace and Company; 1993.

- Jones G., Kennedy S., Barnard A., Wong J., Jenkinson C. Development of an endometriosis quality-of-life instrument: The Endometriosis Health Profile-30. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001; 98(2): 258-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01433-8.

- Бегович Ё., Байгалмаа Б., Солопова А.Г., Бицадзе В.О., Хизроева Д.Х., Сон Е.А., Зобаид Ш.Х., Быковщенко Г.К. Качество жизни как критерий оценки эффективности реабилитационных программ у пациенток с болевой формой наружного генитального эндометриоза. Акушерство, гинекология и репродукция. 2023; 17(1): 92-103. [Begovich E., Baigalmaa B., Solopova A.G., Bitsadze V.O., Khizroeva J.Kh., Son E.A., Zobaid Sh.Sh., Bykovshchenko G.K. Quality of life as a criterion for assessing the effectiveness of rehabilitation programs in patients with painful external genital endometriosis. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2023; 17(1): 92-103. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2023.391.

- Rabin R., de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann. Med. 2001; 33(5): 337-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07853890109002087.

- Brooks R., Boye K.S., Slaap B. EQ-5D: a plea for accurate nomenclature. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes. 2020; 4(1): 52. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s41687-020-00222-9.

- Александрова Е.А., Хабибуллина А.Р., Аистов А.В., Гарипова Ф.Г., Герри К.Дж., Давитадзе А.П., Заздравных Е.А., Кислицын Д.В., Кузнецова М.Ю., Купера А.В., Мейлахс А.Ю., Мейлахс П.А., Родионова Т.И., Тараскина Е.В., Щапов Д.С. Российские популяционные показатели качества жизни, связанного со здоровьем, рассчитанные с использованием опросника EQ-5D-3L. Сибирский научный медицинский журнал. 2020; 40(3): 99-107. [Aleksandrova E.A., Khabibullina A.R., Aistov A.V., Garipova F.G., Gerry Ch.J., Davitadze A.P., Zazdravnykh E.A., Kislitsyn D.V., Kuznetsova M.Yu., Kupera A.V., Meylakhs A.Yu., Meylakhs P.A., Rodionova T.I., Taraskina E.V., Shchapov D.S. Russian population health-related quality of life indicators calculated using the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire. Siberian Scientific Medical Journal 2020; 40(3): 99-107. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.15372/SSMJ20200314.

- Williamson A., Hoggar B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 2005; 14(7): 798-804. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01121.x.

- Яхно Н.Н., ред. Боль. Руководство для врачей и студентов. М.: МЕДпресс-информ; 2009. 304 с. [Yakhno N.N., ed. Pain. Guidance for physicians and students. Moscow: MEDpress-inform; 2009. 304 p. (in Russian)].

- Sullivan M.J.L., Bishop S.R., Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995; 7(4): 524-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524.

- Радчикова Н.П., Адашинская Г.А., Саноян Т.Р., Шупта А.А. Шкала катастрофизации боли: адаптация опросника. Клиническая и специальная психология. 2020; 9(4): 169-87. [Radchikova N.P., Adashiskaya G.A., Sanoyan T.R., Shupta A.A. Russian adaptation of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Clinical Psychology and Special Education. 2020; 9(4): 169-87. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17759/cpse.2020090409.

- Манагадзе И.Д., Нестерова А.А., Левакова О.С., Леваков С.А. Психоэмоциональные аспекты и соматический статус женщин с эндометриозом – есть ли связь? Акушерство и гинекология. 2024; 11: 21-33. [Managadze I.D., Nesterova A.A., Levakova O.S., Levakov S.A. Psychoemotional aspects and somatic status of women with endometriosis: is there a link? Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024; (11): 21-33 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.185.

- Wei Y., Liang Y., Lin H., Dai Y., Yao S. Autonomic nervous system and inflammation interaction in endometriosis-associated pain. J. Neuroinflammation. 2020; 17(1): 80. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01752-1.

- Fadhlaoui A., Gillon T., Lebbi I., Bouquet de Jolinière J., Feki A. Endometriosis and vesico-sphincteral disorders. Front. Surg. 2015; 2: 23. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2015.00023.

- Лисовская Е.В., Хилькевич Е.Г., Чупрынин В.Д., Мельников М.В., Ипатова М.В. Качество жизни женщин с глубоким инфильтративным эндометриозом. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 3: 116-26. [Lisovskaya E.V., Khilkevich E.G., Chuprynin V.D., Melnikov M.V., Ipatova M.V. Quality of life in patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (3): 116-26. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.116-126.

- Бегович Ё., Солопова А.Г., Хлопкова С.В., Сон Е.А., Идрисова Л.Э. Качество жизни и особенности психоэмоционального статуса больных наружным генитальным эндометриозом. Акушерство, гинекология и репродукция. 2021; 16(2): 122-33. [Begovich E., Solopova A.G., Khlopkova S.V., Son E.A., Idrisova L.E. Quality of life and psychoemotional status in patients with external genital endometriosis. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2022; 16(2): 122-33. (in Russian)]. h https://dx.doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2022.283.

- Lerman S.F., Rudich Z., Brill S., Shalev H., Shahar G. Longitudinal associations between depression, anxiety, pain, and pain-related disability in chronic pain patients. Psychosom. Med. 2015; 77(3): 333-41. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000158.

- Mechsner S. Ganzheitliche Behandlung der Endometriose [Holistic treatment of endometriosis]. Schmerz. 2023; 37(6): 437-47. (in German). https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00482-023-00747-0.

- Dowding C., Mikocka-Walus A., Skvarc D., Van Niekerk L., O'Shea M., Olive L. et al. The temporal effect of emotional distress on psychological and physical functioning in endometriosis: a 12 month prospective study. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being. 2023; 15(3): 901-18. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12415.

- Sherman K.A., Pehlivan M.J., Redfern J., Armour M., Dear B., Singleton A. et al. A supportive text message intervention for individuals living with endometriosis (EndoSMS): Randomized controlled pilot and feasibility trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2023; 32: 101093. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101093.

- De Hoyos G., Ramos-Sostre D., Torres-Reverón A., Barros-Cartagena B., López-Rodríguez V., Nieves-Vázquez C. et al. Efficacy of an environmental enrichment intervention for endometriosis: a pilot study. Front. Psychol. 2023; 14: 1225790. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1225790.

- Nieves-Vázquez C.I., Detrés-Marquéz A.C., Torres-Reverón A., Appleyard C.B., Llorens-De Jesús A.P., Resto I.N. et al. Feasibility and acceptability of an adapted environmental enrichment intervention for endometriosis: A pilot study. Front. Glob. Womens Health. 2023; 3: 1058559. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.1058559.

- Merlot B., Dispersyn G., Husson Z., Chanavaz-Lacheray I., Dennis T., Greco-Vuilloud J. et al. Pain reduction with an immersive digital therapeutic tool in women living with endometriosis-related pelvic pain: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022; 24(9): e39531. https://dx.doi.org/10.2196/39531.

Received 01.08.2024

Accepted 14.02.2025

About the Authors

Sergey A. Levakov, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, N.V. Sklifosovsky ICM, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Healthof Russia (Sechenov University), 119991, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8, bld. 2, +7(495)609-14-00, levakoff@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4591-838X

Tatyana A. Gromova, PhD, Teaching Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Faculty of Medicine, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health

of Russia (Sechenov University), 119991, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str. 8, bld. 2, +7(495)609-14-00, tgromova928@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6104-9842

Nana R. Titova, Deputy Head of the Center for Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain, Head of the Consultative and Diagnostic Department, Clinical Hospital No. 85 of the FMBA

of Russia, 115409, Russia, Moscow, Moskvorech’e str., 16, +7(499)782-85-85, titova_nana@mail.ru

Margarita S. Aslanova, Senior Lecturer at the Department of Pedagogy and Medical Psychology, Institute of Psychological and Social Work, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119991, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8, bld. 2, +7(495)609-14-00; Researcher at the Laboratory of Virtual Reality and Polymodal Perception, FSC PMR, 125009, Russia, Moscow, Mokhovaya str., 9, bld. 4, aslanova_m_s@staff.sechenov.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3150-221X

Ioanna J. Managadze, Student, N.V. Sklifosovsky ICM, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University),

119991, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8, bld. 2, +7(495)609-14-00, ktb1966@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8745-9372

Corresponding author: Ioanna J. Managadze, ktb1966@mail.ru