Post-COVID syndrome in pregnant women with a history of mild and moderate COVID-19

Malgina G.B., Dyakova M.M., Bychkova S.V., Shikhova E.P., Klimova L.E.

Objective: This study aimed to investigate the characteristic features of the course of post-COVID syndrome in women with a history of mild and moderate forms of novel coronavirus infection (NCVI) at different gestational ages.

Materials and methods: The study group (n=200) was divided into three subgroups: subgroup 1 (n=22) with NCVI in the 1st trimester, subgroup 2 (n=76) with NCVI in the 2nd trimester, and subgroup 3 (n=102) with NCVI in the third trimester. The control group (n=99) included women without a history of acute respiratory viral infections (ARVI) during pregnancy. The mean gestational age at the time of the study was 38.3 weeks (37.0–40.2) in the study group and 38.2 weeks (37.1–40.2) in the control group (p=0.1). The time between the disease and the study was more than 20 weeks in subgroup 1 (mean 31.3 (1.1) weeks), 13–20 weeks in subgroup 2 (17.6 (1.1) weeks), and 4–12 weeks in subgroup 3 (6.9 (1.0) weeks). An online survey and psychological research were conducted.

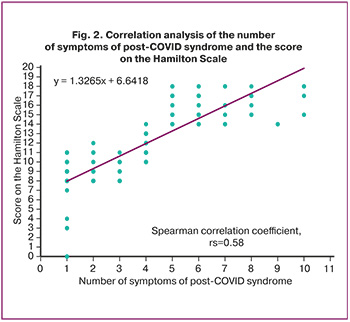

Results: Symptoms not explained by an alternative diagnosis were detected in 93.0% of the pregnant women in the study group and in 38.4% of the women in the control group (p<0.001). The most common symptoms in pregnant women of the study and control groups included cognitive impairment (78.0% vs. 19.2%), distortion of smell and taste (47.5% vs. 0.0%), dry mouth (27.5% vs. 9.1%), fatigue when performing household work (27.0% vs. 9.1%), and weakness (26.0% vs. 8.1%). In the study group, 90.0% and 59.6% of the women in the control group had psychological disorders. Pregnant women with NCVI in the first trimester were significantly more likely to be at risk of developing post-COVID disorders that persisted until full-term pregnancy. A correlation was established between the number of symptoms of post-COVID syndrome and the Hamilton Depression Scale score (r=0.58; 95% CI 0.81–0.89, p<0.001).

Conclusion: The data obtained allowed us to substantiate the need for rehabilitation measures in pregnant women after NCVI, depending on the severity and duration of post-COVID symptoms.

Authors’ contributions: Malgina G.B. – conception and design of the study, manuscript drafting and editing; Dyakova M.M. – data collection and analysis, manuscript drafting; Bychkova S.V. – literature search of Russian and foreign studies in Russian and international databases, analysis of published studies; Shikhova E.P. – material collection (psychological study of female patients); Klimova L.E. – material collection.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Ural Research Institute of Maternity and Child Care (Ref. No. 12 dated 21.09.2021).

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors’ Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Malgina G.B., Dyakova M.M., Bychkova S.V., Shikhova E.P., Klimova L.E. Post-COVID syndrome in pregnant women with a history of mild and moderate COVID-19.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (12): 87-94 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.215

Keywords

The clinical impact of COVID-19 may extend beyond the acute infectious period, leading to long-term consequences of the novel coronavirus infection (NCVI), which significantly affects the health and quality of life of affected individuals. This presents a substantial global health concern, prompting a recent focus on the long-term effects of COVID-19.

In 2020, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) introduced a new classification called "Post COVID-19 condition, unspecified." [1]. Additionally, the updated Clinical Guidelines for the treatment of patients with COVID-19, released at the beginning of 2021, included a chapter on "Care for patients with COVID-19 after acute illness." [2].

While the issue of post-COVID syndrome is actively being studied, there is a scarcity of data on its course in pregnant women in the available literature [3–5].

This study aimed to investigate the characteristic features of the course of post-COVID syndrome in women with a history of mild and moderate forms of novel coronavirus infection (NCVI) at different gestational ages.

Materials and methods

This was a single-center, prospective cohort study [6]. To assess the clinical manifestations of post-COVID syndrome, an online questionnaire was compiled and developed in the Google Forms Google application [7]. The questionnaire consisted of 40 questions of open, closed, semi-closed, evaluative, and control type.

The psycho-emotional state of the pregnant women was studied using the Hamilton test (HRDS, 1960) [8]. Patients were given sufficient time to answer the question in detail but were not allowed to deviate from the topic of the question. The results were interpreted by summing the scores of the first 17 items of the scale according to the following scheme: 0–7 – normal; 8–13 – mild depressive disorder; 14–18 – moderate depressive disorder; 19–22 – severe depressive disorder; and >23 – extremely severe depressive disorder.

The study group (n=200) included pregnant women who had NCVI at a mean gestational age at the time of the disease of 24.4 (9.3) weeks and a mean gestational age at the time of their examination of 38.3 [37.0–40.2] weeks.

The criteria for inclusion in the study group were mild to moderate NCVI at a gestation period of 6 or more weeks, signed informed consent to participate in the study, and clinical recovery at the time of the study. The exclusion criterion was the acute phase of COVID-19.

To assess the duration of symptoms of post-COVID syndrome in pregnant women, the study group was divided into the following subgroups:

Subgroup 1 (n=22) included patients who had NCVI within 6-12.6 weeks of gestation (first trimester). The mean gestational age at the time of infection was 6.8 (4.0) weeks, and the mean gestational age at the time of examination was 38.1 [37.1–40.2] weeks. The time between the onset of NCVI and the start of the study was > 20 weeks (mean 31.3 (1.1) weeks).

Subgroup 2 (n=76) included patients who had NCVI at 13.0-27.6 weeks of gestation (II trimester), mean gestational age at the time of NCVI was 20.6 (4.3) weeks, gestational age at study entry was 38.2 [37.0–40.1] weeks. The interval between the NCVI and study entry was 13–20 weeks (17.6 (1.1) weeks).

Subgroup 3 (n=102) included patients who had NCVI at 28 weeks or more (III trimester), mean gestational age at time of infection was 31.5 (3.3) weeks, gestational age at study entry was 38.4 [37.2–40.0] weeks. The interval between NCVI and study entry was 4–12 weeks (6.9 (1.0) weeks).

The control group comprised 99 full-term pregnant patients without signs of acute respiratory viral infection (ARVI) during pregnancy and at the time of the study. The control group sample size was calculated using a power calculator [9]. The gestational age at the time of the study of patients in the control group was 38.2 [37.1–40.2] weeks.

Evaluation of patients in the study and control groups was carried out at full-term pregnancy; no significant differences were found in gestational age at the time of the study (p=0.1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel (2010) and SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Microsoft, USA). For comparison of the three independent subgroups by categorical variables, 2×2 contingency tables and χ2 test were used. Categorical variables are reported as counts and proportions (%). The hypothesis about the normal distribution of the sample was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. The equality of variances was tested using the F-test in the SPSS Statistics package version 22.0, which is directly included in the procedure for testing the hypothesis regarding the difference in means. Quantitative variables showing a normal distribution were expressed as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) and presented as M (SD. Relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated to estimate the likelihood of a particular event occurring in individuals in the study group exposed to the risk factor relative to the control group. Correlation analysis was conducted by calculating Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for non-normally distributed quantitative variables (׀r׀≤0.25 – weak correlation; 0.25<׀r׀<0.75 – moderate correlation; ׀r׀ ≥0. 75; strong correlation). Statistical significance was assumed at p<0.05. When comparing more than two groups, the Bonferroni correction was used (p<0.017).

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Ural Research Institute of Maternity and Child Care (Ref. No. 12 dated 21.09.2021).

Results and discussion

Long COVID-19 is a multisystem disease [10–16]. To date, several hypotheses have been proposed for its pathogenesis, including the persistence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in tissues [10], immune dysregulation [11] due to molecular mimicry [12], effects on the microbiota [13], virome [14], microvascular coagulation in endothelial dysfunction [15], and dysfunctional signaling in the nervous system [16].

Long COVID-19 is associated with all ages and acute illness severity, with the highest percentage of diagnoses occurring between the ages of 36 and 50. The majority of long COVID-19 cases occur in non-hospitalized patients with mild acute illness [17].

In our study, the mean age of the patients in the study group at the time of the study was 30.8 (5.9) years: in subgroup 1 – 31.8 (4.0) years; in subgroup 2 – 31.3 (5.9) years; and in subgroup 3 – 30.2 (6.5) years. The age of the patients in the control group was 30.9 (6.8) years.

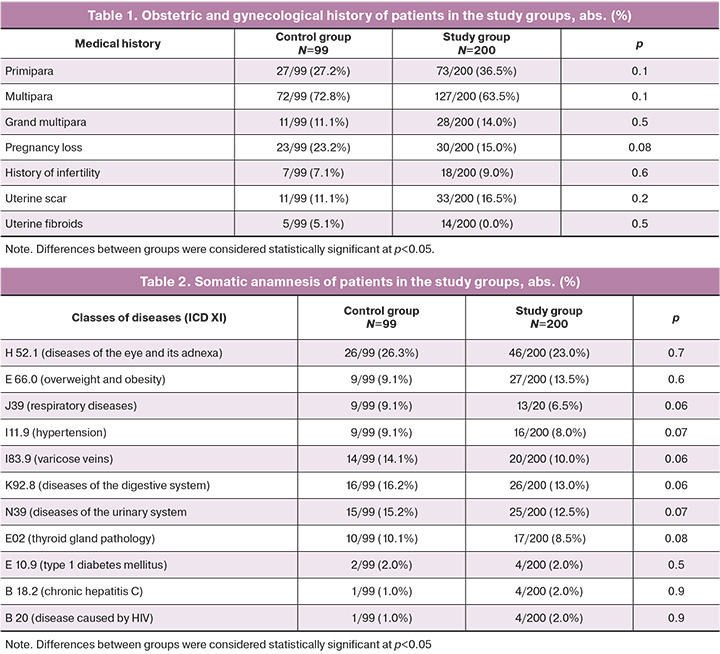

At the time of the study, the study and control groups were comparable in age, obstetric-gynecological, and somatic history (p>0.05) (Tables 1 and 2).

According to an Office for National Statistics (ONS) survey, 2 million people in the UK had long COVID-19, of whom 72% reported long COVID-19 for 12 weeks, 42% for 1 year, and 19% for 2 years [18]. A prospective cohort study of 4182 COVID-19 cases found that 13.3, 4.5, and 2.5% of patients had symptoms of long COVID-19 for ≥28 days, ≥8 weeks, and ≥12 weeks, respectively [19].

The incidence of long COVID-19 is estimated to be 10–30% of non-hospitalized, 50–70% of hospitalized patients [20, 21], and 10–12% of vaccinated cases [22, 23]. We did not find any information in the international literature on the incidence of post-COVID syndrome among pregnant women.

We conducted a survey of pregnant women in the study and control groups during full-term pregnancy to identify symptoms that could not be explained by alternative diagnoses. The presence of at least one symptom was considered a manifestation of the post-COVID syndrome.

Clinical manifestations of post-COVID syndrome were observed in 186/200 (93.0%) pregnant women in the study group; the majority of them, 148/186 (79.6%) had 1–5 symptoms, and 38/186 (20.4%) had 6–10 symptoms; only 14/200 (7.0%) patients had no post-COVID symptoms. Pregnant women in the control group were 2.4 times less likely to experience such symptoms (38/99 (38.4%, p<0.001)).

Our results are consistent with those reported by Belokrinitskaya T.E. et al. (2023). According to their opinion, the prevalence of post-COVID syndrome in pregnant women was 93.7%, which did not differ significantly from non-pregnant patients (97.2%) [5].

Currently, there are no clear symptoms characteristic of COVID-19. When analyzing the literature, we identified the most common symptoms of post-COVID syndrome in the general population: general, respiratory, neuropsychological, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal.

Common symptoms include fatigue (23–53%), arthralgia (10–26%), weight change (10.6–20.0%), myalgia (6–27%), and diaphoresis (6–10%) [24, 25]. Manifestations of dysfunction of the respiratory system include shortness of breath (14–35%), cough (5–40%), chest pain (5–29%), pulmonary fibrosis (0.6–1.0%) [26, 27]. Neurological disorders such as cognitive impairment (9–50%), anosmia (6–36%), headache (5–33%), dizziness (4–29%), ageusia (4–7%), stroke (0.1%) are the next most common [28, 29]. Cardiovascular disorders include a feeling of pressure in the chest (48%), rapid heartbeat at rest (5–44%), cardiac arrhythmia (11.2%), acute coronary syndrome (4.0%), and new-onset hypertension (1%) [28, 29]. Gastrointestinal manifestations close to the list of post-COVID problems include loss of appetite (6–14%), abdominal pain (4–10%), stool disturbances (3–21%), and nausea and vomiting (0.3–2%) [28, 29].

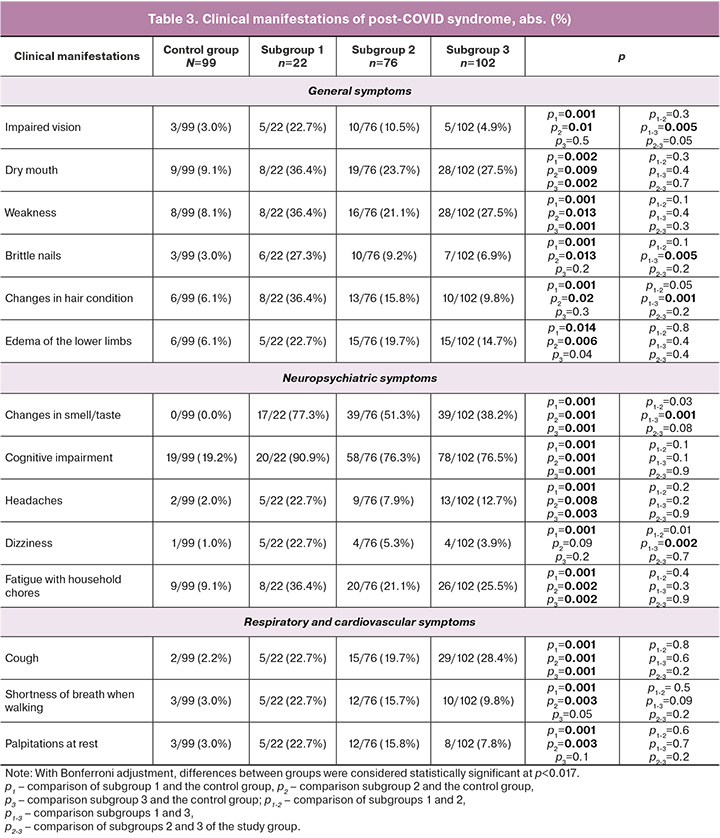

In our study, the most common manifestations of post-COVID syndrome in pregnant women in the study group were cognitive impairment (156/200 (78.0%)), disturbances in sleep, memory, and concentration, distortion of smell and taste (95/200 (47.5%)), dry mouth (55/200 (27.5%)), fatigue when performing household chores (54/200 (27.0%)), and weakness (52/200 (26.0%)). Similar symptoms occurred significantly less frequently in the control group: cognitive impairment (19/90 (19.2%)), dry mouth (9/99 (9.1%)), fatigue when performing household chores (9/99 (9.1%)), and weakness (8/99 (8.1%)) (Table 3). In a study by domestic authors, fatigue and memory impairment were common symptoms (71.2 %, 71.8 %, and 54.1 %, respectively) [5].

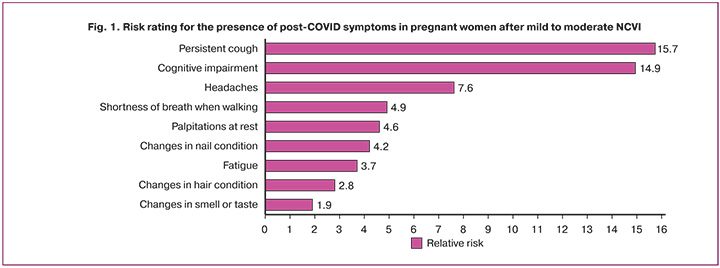

Based on our data, we compiled a risk rating for the presence of post-COVID symptoms in pregnant women after mild and moderate NCVI (Fig. 1). Persistent cough after acute COVID-19 was ranked first (RR=15.7; 95% CI 3.7–66.2, p=0.001), followed by the development of cognitive impairment (RR=14.9; 95% CI 8.2–27.2, p=0.001) and headache (RR=7.6; 95% CI 1.8–32.5, p=0.002), which were not explained by an alternative diagnosis. Other symptoms: shortness of breath when walking on level ground (RR=4.9; 95% CI 1.5–16.9, p=0.005), palpitations at rest (RR=4.6; 95% CI 1.3–15 .5, p=0.008), changes in the condition of nails (RR=4.2; 95% CI 1.2–14.2, p=0.014) and hair (RR=2.8; 95% CI 1.1–7.1, p=0.02), rapid fatigue when performing household chores (OR=3.7; 95% CI 1.7–7.9, p=0.001), and distortions of smell and taste (OR=1.9; 95% 1.7–2.2, p=0.001). On psychological examination, there was an increased risk of moderate (RR=2.4; 95% CI 1.3–4.5, p=0.005) and mild depressive disorder (RR=1.9; 95% CI 1.2–3.1, p=0.001).

A detailed analysis of the results by subgroups of the study group revealed that pregnant women who had NCVI in the first trimester (subgroup 1) were significantly more likely to have clinical manifestations of post-COVID syndrome compared to those who had NCVI in the second and third trimesters. It is noteworthy that according to the survey data, their post-COVID symptoms persisted until full-term pregnancy. Patients who had NCVI in the first trimester (subgroup 1) significantly more often complained of visual impairment (5/22 (22.7%) versus 10/76 (10.5%) (subgroup 2) and 5/ 102 (4.9%) (subgroup 3), p=0.005), brittle nails (6/22 (27.3%) vs. 10/76 (9.2%) and 7/102 (6.9 %), p=0.005), change in hair condition (8/22 (36.4%) vs. 13/76 (15.8%) and 10/102 (9.8%), p=0.001), odor and taste distortion (17/22 (77.3%) vs. 39/76 (51.3%) and 39/102 (38.2%), p=0.001), and dizziness (5/22 (22.7%) vs. 4 /76 (5.3%) and 4/102 (3.9%), p=0.002) (Table 3).

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, 22% of women experienced high levels of anxiety during pregnancy [30]. NCVI has caused an increase in the proportion of pregnant women with psychoemotional disorders, manifested by depressive disorders and anxiety (26.0–34.2%) [31]. A study by Wang С. et al. (2020) [32] reported that women's anxiety levels were 3.01 times higher than those of men during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a study by Geren A. et al. (2021), 30.7% of pregnant women had depression: 12.4% – mild, 12.4% – moderate, 5.9% – severe [33].

In our study, psychological disorders in the study group occurred in 180/200 (90.0%) pregnant women (mild depression in 120/200 (60.0%), moderate depression in 60/200 (30. 0%) patients), and 20/200 (10.0%) had a normal psychological state. In the control group, mild depression was found in 44/99 (44.4%), moderate depression in 15/99 (15.2%) (p<0.001), and normal psychological health in 40/99 (40.4 %) pregnant women (p<0.001).

We did not identify severe depression but established a positive correlation (׀r׀>0.75) between the number of symptoms of post-COVID syndrome and the degree of depression in pregnant women after mild to moderate NCVI (Spearman correlation coefficient rs=0.58; 95% CI 0 .81–0.89, p<0.001) (Fig. 2). We did not find this information in the literature.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate the development of post-COVID syndrome in pregnant women with mild to moderate forms of NCVI. The proportion of pregnant women with clinical manifestations of post-COVID syndrome was 93.0%, of which most women have from 1 to five symptoms (79.6%), every fifth pregnant woman (20.4%) had 6 to 10 symptoms, and 90.0% of patients had psychological disorders. Pregnant women who experienced the disease in the first trimester were significantly more likely to be at risk of developing post-COVID disorders that persisted until full-term pregnancy. A correlation has been established between the number of symptoms of post-COVID syndrome and the Hamilton Scale score in pregnant women with mild to moderate NCVI.

The results of the study allowed us to substantiate the need for rehabilitation in pregnant women after NCVI, depending on the severity and duration of post-COVID symptoms.

References

- World Health Organization. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. https://icd.who.int/ru

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Временные методические рекомендации. Организация оказания медицинской помощи беременным, роженицам, родильницам и новорожденным при новой коронавирусной инфекции COVID-19. Версия 4 от 05.07.2021. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Organization of medical care for pregnant women, women in labor, women in labor and newborns with a new coronavirus infection COVID-19. Methodological guidelines. Version 4, 05.07.2021 – 2021 (in Russian)].

- Alfayumi-Zeadna S., Bina R., Levy D., Merzbach R., Zeadna A. Elevated perinatal depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national study among jewish and arab women in Israel. J. Clin. Med. 2022; 11(2): 349.https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.208.

- Адамян Л.В., Вечорко В.И., Конышева О.В., Харченко Э.И., Дорошенко Д.А. Постковидный синдром в акушерстве и репродуктивной медицине. Проблемы репродукции. 2021; 27(6): 30‑40. [Adamyan L.V., Vechorko V.I., Konysheva O.V., Kharchenko E.I., Doroshenko D.A. Post-COVID-19 syndrome in Obstetrics and Reproductive Medicine. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2021; 27(6): 30‑40. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro20212706130.

- Белокриницкая Т.Е., Фролова Н.И., Мудров В.А., Каргина К.А., Шаметова Е.А., Агаркова М.А., Жамьянова Ч.Ц. Постковидный синдром у беременных. Акушерство и гинекология. 2023; 6: 60-8. [Belokrinitskaya T.Е., Frolova N.I., Mudrov V.A., Kargina K.A., Shametova E.A., Agarkova M.A., Zhamiyanova Ch.Ts. Postcovid syndrome in pregnant women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (6): 60-8 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.54.

- von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008; 61(4): 344-9. https://dx.doi.org/0.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

- Создавайте собственный онлайн-опрос бесплатно. Главная страница приложения Формы (Google Forms). http://www. google.ru/intl/ru/ forms/about/ (18.03.2015). [Create your own online survey for free. Home page of the Forms application (Google Forms). http://www.google.ru/intl/en/ forms/about/ (18.03.2015) (in Russian)].

- Hamilton M.A. Rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1960; 23(1): 56-62. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56.

- Sealed Envelope Ltd. 2012. Power calculator for binary outcome superiority trial. https://www.sealedenvelope.com/power/binary-superiority

- Proal A.D., VanElzakker M.B. Long COVID or Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): an overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front. Microbiol. 2021; 12: 698169. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.698169.

- Glynne P., Tahmasebi N., Gant V., Gupta R. Long COVID following mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: characteristic t cell alterations and response to antihistamines. J. Investig. Med. 2022; 70(1): 61-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jim-2021-002051.

- Phetsouphanh C., Darley D.R., Wilson D.B., Howe A., Munier C.M.L., Patel S.K. et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022; 23(2): 210-16.https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x.

- Zubchenko S., Kril I., Nadizhko O., Matsyura O., Chopyak V. Herpesvirus infections and post-COVID-19 manifestations: a pilot observational study. Rheumatol Int. 2022; 42(9): 1523-30. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05146-9.

- Yeoh Y.K., Zuo T., Lui G.C., Zhang F., Liu Q., Li A.Y. et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2021; 70(4): 698-706.https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323020.

- Wang Z., Yang Y., Liang X., Gao B., Liu M., Li W. et al. COVID-19 Associated ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke: incidence, potential pathological mechanism, and management. Front. Neurol. 2020; 11: 571996.https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.571996.

- Kumari P., Rothan H.A., Natekar J.P., Stone S., Pathak H., Strate P.G. et al. Neuroinvasion and encephalitis following Intranasal Inoculation of SARS-CoV-2 in K18- hACE2 Mice. Viruses. 2021; 13(1): 132.https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/v13010132.

- Azzolini E., Levi R., Sarti R., Pozzi C., Mollura M., Mantovani A., Rescigno M. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and long COVID after infections not requiring hospitalization in health care workers. JAMA. 2022; 328(7): 676-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.11691.

- Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 7 October 2021.

- Sudre C.H., Murray B., Varsavsky T., Graham M.S., Penfold R.S., Bowyer R.C. et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021;27(4): 626-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y.

- Bull-Otterson L., Baca S., Saydah S., Boehmer T.K., Adjei S., Gray S., Harris A.M. Post-COVID conditions among adult COVID-19 survivors aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years — United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR. 2022; 71(21): 713-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7121e1.

- Ceban F., Ling S., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Teopiz K.M., Rodrigues N.B. et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022; 101: 93-135.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020.

- Al-Aly Z., Bowe B., Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2022; 28(7): 1461-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0.

- Ayoubkhani D., Bosworth M.L., King S., Pouwels K.B., Glickman M., Nafilyan V. et al. Risk of long COVID in people infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 After 2 Doses of a coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine: community-based, matched cohort study. Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 2022;9(9): ofac464. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac464.

- Su Y., Yuan D., Chen D.G., Wang K., Choi J., Li S. et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell. 2022; 185(5): 881-895.e20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.014.

- Lopez-Leon S., Wegman-Ostrosky T., Ayuzo Del Valle N.C., Perelman C., Sepulveda R., Rebolledo P.A. et al. Long-COVID in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Sci. Rep. 2022; 12(1): 9950.https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13495-5.

- Zhang X., Wang F., Shen Y., Hang X., Cen Y., Wang B. et al. Symptoms and health outcomes among survivors of COVID-19 Infection i Year After discharge from hospitals in wuhan, China. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021; 4(9): e2127403.https://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27403.

- Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group; Morin L., Savale L., Pham T., Colle R., Figueiredo S., Harrois A. et al. Four-month сinical status of a сohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021; 325(15): 1525-34. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.3331.

- Yang T., Yan M.Z., Li X., Lau E.H.Y. Sequelae of COVID-19 among previously hospitalized patients up to 1 year after discharge: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection. 2022; 50(5): 1067-109. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s15010-022-01862-3.

- Wang S.Y., Adejumo P., See C., Onuma O.K., Miller E.J., Spatz E.S. Characteristics of patients referred to a cardiovascular disease clinic for post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Am. Heart. J. Plus. 2022; 18: 100176.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahjo.2022.100176.

- Palladino C.L., Singh V., Campbell J., Flynn H., Gold K.J. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the national violent death reporting system. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011; 118(5): 1056-63. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da.

- Wu Y., Zhang C., Liu H., Duan C., Li C., Fan J. et al. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am. J. Obste.t Gynecol. 2020; 223(2): 240.e1-240.e9.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.009.

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S. et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2020; 17: 1729. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

- Geren A., Birge Ö., Bakır M.S., Sakıncı M., Sanhal C.Y. Does time change the anxiety and depression scores for pregnant women on Covid-19 pandemic? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021; 47(10): 3516-23. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jog.14935.

Received 07.09.2023

Accepted 18.10.2023

About the Authors

Galina B. Malgina, Professor, Dr. Med. Sci., Director of the Ural Research Institute of Maternity and Child Care, Ministry of Health of Russia, galinamalgina@mail.ru,https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5500-6296, 620028, Russia, Yekaterinburg, Repin str., 1.

Maria M. Dyakova, Junior Researcher, Ural Research Institute of Maternity and Child Care, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(343)37-189-11, +7(950)550-06-52, mariadakova40@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7911-6783, 620028, Russia, Yekaterinburg, Repin str., 1.

Svetlana V. Bychkova, PhD, Leading Researcher, Ural Research Institute of Maternity and Child Care, Ministry of Health of Russia, +7(343)37-189-11,

simomm@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8892-7585, 620028, Russia, Yekaterinburg, Repin str., 1.

Elena P. Shikhova, PhD, Leading Researcher, Ural Research Institute of Maternity and Child Care, Ministry of Health of Russia, ordinatura@niiomm.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7256-9111, 620028, Russia, Yekaterinburg, Repin str., 1.

Luydmila E. Klimova, PhD, Head of Pregnancy Pathology Department No. 1, Ural Research Institute of Maternity and Child Care, Ministry of Health of Russia,

luydmila-klim@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0009-0009-3647-0411, 620028, Russia, Yekaterinburg, Repin str., 1.

Corresponding authors: Maria M. Dyakova, mariadakova40@gmail.com; Svetlana V. Bychkova, simomm@mail.ru