Ways to standardise of fetometry in Russia: INTERGROWTH-21st project and its implementation

The implementation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth and newborn size for gestation age standards into clinical practice in Russia were discussed and debated. The INTERGROWTH-21st Project was implemented in more than eight countries from 2009 to 2018. All study protocols and primary findings are available online (intergrowth21.org). Briefly, eight diverse urban populations living in demarcated geographical areas were selected where: environments were free from major known pollutants; altitude was less than 1600 m; most women accessed antenatal and delivery care in institutions; mean birth weight was greater than 3100 g; rates of low birth weight (< 2500 g) were less than 10%, and perinatal mortality was less than 20 per 1000 births. The INTERGROWTH-21st study comes as a high-quality response to the common dilemma of lack of standardization in fetal growth assessment. Its use should be encouraged among Russian specialists in maternal-fetal medicine, obstetricians and radiologists.Kholin A.M., Gus A.I., Khodzaeva Z.S., Baev O.R., Ryumina I.I., Villar J., Kennedy S., Papageorghiou A.T.

Keywords

Fetal biometry has been debated for decades by the clinicians all over the world. The multiple publications suggest various measurable planes, mathematical formulae, local charts and differentiations in fetal growth that define the charts to be utilized [1].

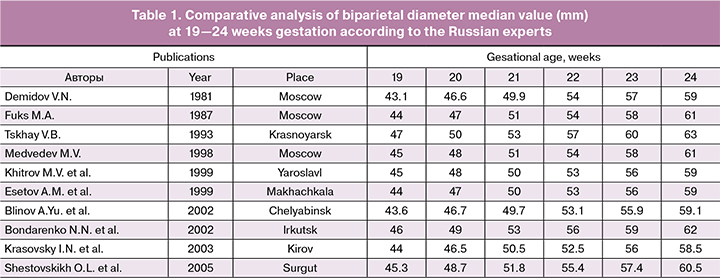

Under the supervision of V.N. Demidov and M.V. Medvedev the most widespread in Russia charts were developed (1988). Among international standards, the regulatory limits introduced by F. Hadlock et al. (1984) are included in obstetrics programs of ultrasounds diagnosis equipment [2]. There are at least 10 fetal growth charts implemented in the Russian clinical practice (Table 1).

Unfortunately, even the same clinical institution often implements various charts for different ultrasound equipment that impedes the fetal growth tracking, confuses parents, clinicians and researchers. Thus, a fetus considered small for gestational age (SGA) by one clinician, can be rated as ‘normal’ at a different reference scale. All these factors result in consultancy complexities and call forth such issues as: What is the reason for such variations? Are such reasons explained by the application of different charts or the quality of the research conducted? Is the fetus rated as ‘risk group’? This situation vividly illustrates the lack of unified ultrasound charts, partly resulting from the lack of unification in echography. The latter is evident due to the results of research conducted in small private clinics and doctor’s consulting rooms.

In general, the fetal growth rate can be estimated by the charts, that 1) result from the observational distribution studies of fetal growth for the gestational age in a certain population; 2) specified by the maternal characteristics such as parity rates, growth, and ethnicity, including the evaluation of fetal weight according to model of Hadlock.

The charts are developed according to the estimation of the healthy patients’ population selected to obtain the optimal fetal growth with the lack of negative growth restrictions and do not depend on the time or place.

SGA is defined as the 10th percentile of the expected fetal growth or abdominal circumference (AC). It should be taken into account that the apparent frequency of SGA is always close to the 10th percentile, in case control or embedded charts are used; in spite of the fact that the frequency of other perinatal conditions varies greatly around the world. For instance, the frequency variations in preeclampsia or diabetes are taken without connections to the local determinants. Thus, it is not logical to consider the confirmation of ‘fixed’ 10% of SGA prevalence.

What fetal growth charts among the hundreds available can be implemented? A unified international standard does not exist, though echography has been used in obstetrics for fifty years. The situation resembles the one that occurred with consensus on optimal growth in pediatrics. It was stated in the 1970-s that the growth of children primarily depends on environment and nutrition rather than ethnic origin [3]. WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS) launched in 1996 was aimed at verification of the above-mentioned hypothesis in all child populations all over the world. The researchers examined 8406 healthy nursing infants under the age of five, in six countries. [4]. They demonstrated that the fetal growth was very much similar [5]. It resulted in developing WHO Child Growth Standards in 2006 that were adapted in more than 130 countries [6]. Unified monitoring of children growth was introduced in Russia in 2012 after WHO recommended the growth charts for all infants aged 0-2.

Current state of affairs in the fetal medicine

Identification of children with insufficient or excessive fetal growth proves to be challenging. There is no consensus on fetal growth monitoring in modern Russia. Neither Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, nor Russian Association of Specialists in Ultrasound Diagnostic in Medicine has ever published any clinical recommendations concerning the application of fetal growth charts. Due to the lack of the published official “Russian standard”, numerous fetal growth charts are used. The choice of the fetal growth chart for the most clinicians is defined by the protocol of their institutions, the recommendations of the professional society, medical information system or the fetal growth chart scale installed in the ultrasound device. However, the charts differ not only in the range of percentiles and trends, but also in the quality of studies they were based on. Thus, two systematic reviews estimated the quality of the published ultrasound charts for verifying the gestational age by means of coccygeal-parietal size and fetal growth monitoring [8]. According to the results of 112 researches, there were several important reasons for methodologic errors, including inability of gestational age estimation; inaccuracy in population differentiation and inclusion/exclusion criteria; imaging standardization protocols deficiency and retrospective analysis of the images for clinical purposes. This resulted in the considerable variations among the threshold requirements of percentile, when different charts were applied: for instance, 10th percentile for abdominometry at 36 weeks gestation ranged between 276 to 292 mm even among the best researches conducted.

INTERGROWTH‐21st Project

The INTERGROWTH-21st Consortium established in 2008, defined that optimal fetal growth among populations was identical enough to conclude that international standard needs to be introduced, identical WHO Child Growth Standards [10]. The Consortium guided by Oxford University team included the group of more than 300 researchers and clinicians. The INTERGROWTH-21st Project was implemented in eight countries from 2009 to 2014. All charts and primary data are accessible online (intergrowth21.org). On the whole, eight various urban populations that live in isolated geographic areas were selected according to the following criteria: environment did not contain any major known pollutants; level above the sea was less than 1600 m; the majority of women received antenatal and obstetric care at the health care institutions; average birthrate increased 3100 g; frequency of low birthweight (<2500 g) was lower that 10% and perinatal mortality was lower than 20 cases per 1000 deliveries [10]. Among the participants of the research were Pelotas, Brazil; Shunui County Beijing, China; Central Nagpur District, India; Turin, Italy; Nairobi, Kenya; Muscat, Oman; Oxford, UK; Seattle, USA.

Within these populations, the mothers underwent screening procedures to estimate if they were eligible to be included into the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study (FGLS) the INTERGROWTH-21st Project component designed for fetal growth and development monitoring from the early stages of pregnancy to infancy. In FGLS fetal biometry was estimated by ultrasonography with highly standardized and masked charts that were developed to minimize the differentiations among the clinical trial [9-11]. The estimations were conducted every five weeks till delivery. Weight, height, and head circumference were estimated in all infants of the whole population [12].

Statistical approaches aimed to define if the estimations of all eight clinical research facilities could be united for obtaining charts were identical to those used in WHO MGRS. The analysis demonstrated that only from 1.9 to 3.5% of differences detected between the linear fetal growth and the infant size resulted from the clinical research facilities [13]. Thus, in accordance with the former monitoring of fetal growth and infant size patterns, the fetal growth and infant size tend to be alike all over the world in case the height restrictions are insignificant. At the age of 12 months after birth, the age growth scale in children in FGLS was almost identical to the measurements of children according to WHO MGRS. This in turn suggests that the data from all of the clinical research facilities can be combined to elaborate international growth charts for fetuses and newborns with focus on how they should grow but not the results of the fetuses in certain places and certain periods of time. The authors suggest that their colleagues should unite their efforts to provide the comprehensive monitoring of the measurement data on pregnant women and children all over the world. Nowadays, there are 23.3 million infants with deficient weight according to the gestational age INTERGROWTH-21st standards. We can imply that the misclassification of these infants’ results from local charts application is very likely to affect the optimal health care provision. [14].

Population relevance for Russia

The INTERGROWTH-21st standards of fetal growth are the most comprehensive available data that correspond to the WHO standards approved for application for the infants in Russia. The following questions rise: To what extent are FLGS standards applicable in Russia? How are the new charts comparable to fetal growth charts implemented now in clinical practice? What standards should be interpreted in clinical practice?

Russia has a high rate of its ethnic and racial diversity. The population of the country is represented by White and Asian races. At a rough estimation, the first group amounts to 90% of the country’s population, and 9% of the people are the mixture of the two mentioned forms. [15] The number of Asian race does not exceed 1 million people. The INTERGROWTH-21 charts proved to be important for such countries as Russia, for the notion ‘race’ tends to lose its importance for every successive generation.

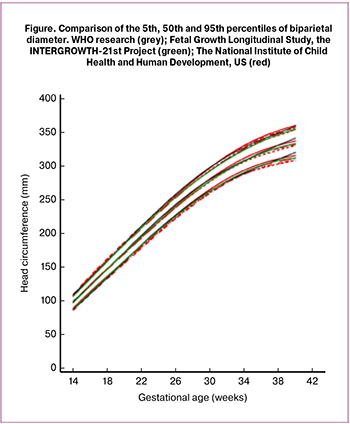

Comparison of researches conducted by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project [16], The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, US (NICHD) [17] World Health Organization (WHO) [18], demonstrated slight discrepancies in fetal head circumference during the gestational age (Figure 1). Comparison of the INTERGROWTH-21st charts with those of Campbell Westerway illustrates their identity. There is a minor variation in biparietal diameter (BPD) resulting from the “external – external” approach in FGLS research, unlike“external - internal” approach to BPD examination. Major variations were observed in the femur length that can be explained by the technical aspects., The the width of the contracted beam in new ultrasound equipment contracts the sizes in the side direction in the INTERGROWTH-21st research [19].

Comparison of researches conducted by the INTERGROWTH-21st Project [16], The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, US (NICHD) [17] World Health Organization (WHO) [18], demonstrated slight discrepancies in fetal head circumference during the gestational age (Figure 1). Comparison of the INTERGROWTH-21st charts with those of Campbell Westerway illustrates their identity. There is a minor variation in biparietal diameter (BPD) resulting from the “external – external” approach in FGLS research, unlike“external - internal” approach to BPD examination. Major variations were observed in the femur length that can be explained by the technical aspects., The the width of the contracted beam in new ultrasound equipment contracts the sizes in the side direction in the INTERGROWTH-21st research [19].

Clinical practice implementation results

It is important for clinical practice to define the cohort of the patients with high risk of fetal growth retardation as this particular group demonstrates higher frequency of morbidity and mortality. Fetal biometry is one of the ways to detect the children with high risk of perinatal or long-term complications. It is essential to conduct further research. First, it is important to examine fetal growth phenotype after the estimation of fetal weight for a certain gestational age. The INTERGROWTH-21st populations showed the strict correlation of the phenotype variations at birth such as growth retardation, underweight, overweight in different neonatal outcomes. This investigation is likely to be a very important research area in the future, when we understand more about the reasons and long-term results of fetal growth.

Taking into account the international character and the scale of the INTERGROWTH-21st, particular attention is paid to the quality of the images and growth similarities among the children in FGLS and MGRS researches 20 years ago. Nowadays, there is evidence of the hypothesis that race has a minimal influence on fetal growth. This fact proves futility of applying different charts for measuring growth of fetuses and newborns. This approach doubts the relevance of race based approach suggested in some charts.

The clinicians should consider the issues of applying such charts in identification of abnormal growth. Moreover, the following questions rise. Should the women who do not live in “the ideal” environment of the centers where the INTEGROWTH-21st research was conducted expect the identical fetal growth figures? iCan the INTERGROWTH-21st percentiles be considered a baseline for pregnancy follow-up strategies? Can such interventions lead to the decline in morbidity and mortality rates connected with the abnormal fetal rates? Nowadays these issues are not tackled.

The Ultrasound Congress “Ultrasound Diagnostics in Obstetrics, Gynecology and perinatology: from basic principles to the innovative approaches” (led by Prof. A.I. Gus, Prof. V.N. Demidov) was held in Moscow in September of 2018 in Moscow within the framework of the Russian Science and Education Forum ‘Mother and Child’. Prof. Aris Papageorghiou, Prof. S. Kennedy, Prof. J. Villar and others presented the series of scientific reports on the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Expert meeting on the issues of clinical implementation of the INTERGROWTH-21st charts in Russia is planned. Such issues as weight gain of pregnant women, early gestation age determination, fetal growth and its correspondence to the gestation age are also going to be covered. Further publications will focus on the development of the project.

References

- Romero R., Tarca A.L. Fetal size standards to diagnose a small- or a large-for-gestational-age fetus. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2018, 218(2, Supplement):S605-S607.

- Makarov I.O., Yudina E.V., Borovkova E.I. Retarded fetal growth. Medical tactics, 2nd edition. Moscow: MEDpress-inform; 2014. (in Russian)

- Habicht J.P., Martorell R., Yarbrough C., Malina R.M., Klein R.E. Height and weight standards for preschool children. How relevant are ethnic differences in growth potential? Lancet. 1974; 1(7858): 611-614.

- MGRSG: Enrolment and baseline characteristics in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta paediatrica. 1992; Supplement 2006, 450: 7-15.

- MGRSG: WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta paediatrica. 1992; Supplement 2006, 450: 76-85.

- de Onis M., Onyango A., Borghi E., Siyam A., Blossner M., Lutter C. Worldwide implementation of the WHO Child Growth Standards. Public health nutrition. 2012; 15(9): 1603-1610.

- NHMRC: National Health and medical Resarch Council. Infant Feeding Guidelines. In. Caanberra; 2012.

- Ioannou C., Talbot K., Ohuma E., Sarris I., Villar J., Conde-Agudelo A., Papageorghiou A.T. Systematic review of methodology used in ultrasound studies aimed at creating charts of fetal size. BJOG. 2012; 119(12): 1425-1439.

- Ioannou C., Sarris I., Hoch L., Salomon L.J., Papageorghiou A.T., for the International F, Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st C: Standardisation of crown–rump length measurement. BJOG. 2013; 120(Suppl s2): 38-41.

- Wanyonyi S.Z., Napolitano R., Ohuma E.O., Salomon L.J., Papageorghiou A.T. Image-scoring system for crown-rump length measurement. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology. 2014; 44(6): 649-654.

- Sarris I., Ioannou C., Ohuma E.O., Altman D.G., Hoch L., Cosgrove C., Fathima S., Salomon L.J., Papageorghiou A.T., for the International F et al: Standardisation and quality control of ultrasound measurements taken in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013; 120(Suppl s2): 33-37.

- Cheikh Ismail L., Knight H.E., Ohuma E.O., Hoch L., Chumlea W.C., for the International F, Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st C: Anthropometric standardisation and quality control protocols for the construction of new, international, fetal and newborn growth standards: the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013; 120(Suppl s2): 48-55.

- Villar J., Papageorghiou A.T., Pang R., Ohuma E.O., Cheikh Ismail L., Barros F.C., Lambert A., Carvalho M., Jaffer Y.A., Bertino E. et al: The likeness of fetal growth and newborn size across non-isolated populations in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study and Newborn Cross-Sectional Study. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2014; 2(10): 781-792.

- Papageorghiou A.T., Kennedy S.H., Salomon L.J., Altman D.G., Ohuma E.O., Stones W., Gravett M.G., Barros F.C., Victora C., Purwar M. The INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards: toward the global integration of pregnancy and pediatric care. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018; 218(2, Supplement): S630-S640.

- Tavadov G.T. Ethnology. Textbook for high schools. Moscow: The project; 2002. (in Russian)

- Dwyer-Lindgren L., Bertozzi-Villa A., Stubbs R.W., Morozoff C., Mackenbach J.P., van Lenthe F.J., Mokdad A.H., Murray C.J.L. Inequalities in Life Expectancy Among US Counties, 1980 to 2014: Temporal Trends and Key Drivers. JAMA internal medicine. 2017; 177(7): 1003-1011.

- Dwyer-Lindgren L., Stubbs R.W., Bertozzi-Villa A., Morozoff C., Callender C., Finegold S.B., Shirude S., Flaxman A.D., Laurent A., Kern E. et al. Variation in life expectancy and mortality by cause among neighbourhoods in King County, WA, USA, 1990-2014: a census tract-level analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet Public health. 2017; 2(9): e400-e410.

- de Onis M., Garza C., Onyango A.W., Borghi E. Comparison of the WHO child growth standards and the CDC 2000 growth charts. The Journal of nutrition. 2007; 137(1): 144-148.

- Okland I., Bjastad T.G., Johansen T.F., Gjessing H.K., Grottum P., Eik-Nes S.H. Narrowed beam width in newer ultrasound machines shortens measurements in the lateral direction: fetal measurement charts may be obsolete. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology. 2011; 38(1): 82-87.

Received 17.02.2018

Accepted 02.03.2018

About the Authors

Alexey Kholin, M.D., Clinical & Research Fellow, Department of Maternal Fetal Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecologyand Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov, Ministry of Health of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: a_kholin@oparina4.ru

Alexander Gus, M.D., Ph.D., Head of Ultrasound Department, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named

after Academician V.I. Kulakov, Ministry of Health of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4

Zulfiya Khodzhaeva, M.D., Ph.D., Professor, Principal Investigator, Department of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics,

Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov, Ministry of Health of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4

Oleg R. Baev, Dr.Med.Sci., Professor, Head of the Maternity Department, National Medical Research Center of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology,

Ministry of Health of Russia; Professor of the Department of Neonatology of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia.

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: o_baev@oparina4.ru

Irina I. Ryumina, MD, head of the department. Department of Pathology of Newborns and Premature Children, National Medical Research Center of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia; Professor of the Department of Neonatology of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4. E-mail: i_ryumina@oparina4.ru

Stephen Kennedy, MD, FRCOG, Head of Department, Professor of Reproductive medicine & Co-director of the Oxford Maternal & Perinatal Health Institute,

Oxford, UK

Jose Villar, MD, MPH, FRCOG, Professor of Perinatal Medicine & Co-Director of the Oxford Maternal & Perinatal Health Institute, Oxford, UK

Aris. T. Papageorghiou, MD, FRCOG, Nuffield Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Oxford maternal * Perinatal Health Institute, Green Templeton College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

For citations: Kholin A.M., Gus A.I., Khodzaeva Z.S., Baev O.R., Ryumina I.I., Villar J., Kennedy S., Papageorghiou A.T. Ways to standardise of fetometry in Russia: INTERGROWTH-21st project and its implementation. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; (9): 170-5. (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2018.9.170-175