Complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy: search for risk factors

Objective: To identify risk factors of complications after laparoscopic hysterectomy.Volkov O.A., Shramko S.V., Renge L.V., Saltykova P.E., Sabantsev M.A., Shisheya E.Yu., Koval E.Yu., Vlasenko A.E., Chubar E.A.

Materials and methods: The study enrolled 87 patients who underwent endoscopic total hysterectomy for uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. Of these, vaginal cuff closure was performed by transvaginal sutures (n=54, 62.1%) or intracorporeal sutures (n=33, 37.9%).

Results: Total vaginal cuff dehiscence was observed in 11 cases, of which 10 cases manifested by bleeding and one by eventration. Infectious complications were registered in five cases including two surgical site (ICSS) infections, two peritonitis, and one peritonitis concurrent with ICSS. The following risk factors for complications after laparoscopic hysterectomy were established: reproductive age, adenomyosis, obesity, respiratory diseases, transvaginal vaginal cuff suture, subcompensated or decompensated blood flow in the vaginal branch of the uterine artery (IR≥0.8) or its absence on the 2nd day after surgery and leukocyte intoxication index ≥2 on the 3rd day after surgery.

Conclusion: Identification of risk factors for complications after laparoscopic hysterectomy will prevent patients from re-hospitalization by optimizing pre-surgical planning of surgical access, choosing method of vaginal cuff closure, and determination of terms of discharge.

Keywords

Hysterectomy is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures among women; on average, one third of women over 50 years of age undergo hysterectomy [1]. Uterine leiomyoma and adenomyosis are the most common indication for total hysterectomy [2]. The world's first report of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) was published in 1989. Since then, the rate of this surgical procedure has increased from 1% to 28%. Conflicting views on the high cost of TLH are still under debate [3, 4]. TLH has been associated with decreased trauma, nausea, vomiting, and pain, early activation and the beginning of oral nutrition, the possibility of accelerated rehabilitation and early discharge from the hospital, and, most importantly, patient satisfaction with the quality of medical care [5]. At the same time, the complication rates of endoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy are comparable, but some complications are specific to laparoscopy. For example, vaginal cuff dehiscence (VCD) after laparoscopy with monopolar coagulation to separate the uterus from the vagina occurs 14–35 times more often (4.1%) than after vaginal access (0.29%) and abdominal access (0.12%), where the acute method is used [6]. In this regard, we can assume that the reparative regeneration of the burn surface and tissue dissected by the acute method have qualitative and temporal differences, which explains the high incidence of VCD during endoscopic hysterectomy. Furthermore, unhealthy habits (smoking), some conditions, including vitamin deficiency, exhaustion, immunosuppression, prolonged use of corticosteroids, menopause, history of radiation and chemotherapy, comorbidities such as respiratory diseases, obesity, diabetes mellitus can change wound healing processes, increasing the risk of VCD [7, 8]. As a rule, this complication occurs on the 14th–16th day after hospital discharge and can be life threatening for a patient [9].

This study aimed to identify risk factors of complications after TLH to guide presurgical, choosing suturing methods to close the vaginal cuff, planning the optimal period of hospitalization, and providing rational postoperative care of patients, thereby reducing the number of repeat hospitalizations and related financial costs.

Materials and methods

The course of the postoperative period was retrospectively evaluated in 87 patients after TLH for uterine and adnexal diseases. Of these, vaginal cuff closure was performed by transvaginal sutures (n=54, 62.1%) or intracorporeal sutures (n=33, 37.9%). The study was conducted at the G.P. Kurbatov Novokuznetsk State Clinical Hospital No.1 and Group of companies «Mother and Child Siberia».

Inclusion criteria for the study were the presence of benign uterine and adnexal diseases requiring hysterectomy (fibroids, adenomyosis, their combined forms, benign ovarian tumors), and informed consent of the patient. The exclusion criteria were malignant neoplasms of the uterus and adnexa, cases of conversion to laparotomy, closure of the vaginal cuff during minilaparotomy, and hysterectomy. A total of 58 clinical, anamnestic and perioperative factors were analyzed, including a history of somatic diseases and surgical interventions, indications for surgery (uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, benign ovarian tumors), intraoperative blood loss, duration of closure of the surgery, method of vaginal cuff (intracorporeal, transvaginal), and variations in suture placement (single, continuous). In the postoperative period, the investigations included ultrasound examination, Doppler, color Doppler mapping of the vaginal stump on the 2nd day after surgery, complete blood count on the 3rd day after surgery with calculation of the leukocyte intoxication index (LII) according to Calf-Calif. Postoperative complications were coded according to ICD-10; the duration of follow-up was 6 weeks. Late postoperative complications were recorded in 16 cases, including 10 cases of vaginal cuff mucosa due to its partial insufficiency, two cases of infectious complications of the surgical site (ICSS), two peritonitis, one peritonitis combined with ICSS, and one eventration.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the distribution was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk test, which showed a nonnormal distribution of continuous variables. Quantitative variables were expressed as median (Me) with interquartile range (Q1; Q3) and compared with a nonparametric Mann–Whitney test. Pearson's χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. The Fisher exact test was used when the expected frequency of one or more cells was less than five. Relative odds (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated as a measure of the effect size. Multivariate analysis was performed using binary logistic regression. Variables were selected by direct selection procedure based on the Wald statistic, and the goodness of fit of the model was assessed using the Nagelkerke R2. Differences were considered statistically significant at p≤0.05. Calculations and graphical plots were performed using GraphPad Prism software (v.9.3.0, GPS-1963924) and the R (v.3.6, license GNU GPL2).

Results

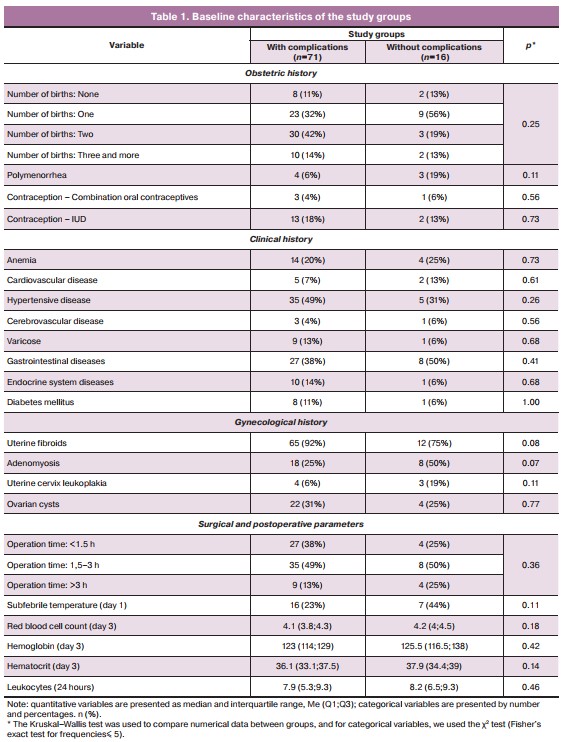

A total of 87 women with a median age of 50 (46; 57) years participated in the study. Late postoperative complications were reported in 16 patients. The analysis showed that the patients without complications and the women in whom there were late postoperative complications were comparable in most of the main parameters of obstetric, gynecological and clinical anamnesis, as well as in the operative intervention and postoperative period (Table 1).

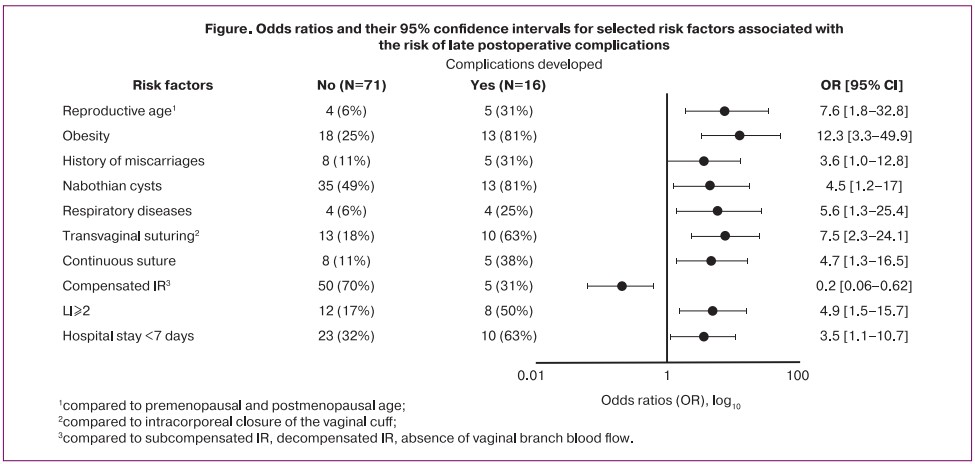

Women who had postoperative complications had higher body mass index than women without complications (Figure). They were more likely to be obese (81% vs. 25%, p<0.001) and of reproductive age (31% vs. 6%, p=0.009), have a history of miscarriage (31% vs. 11%, p=0.05), cervix nabothian cysts (81% vs. 49%, p=0.03), and respiratory disease (25% vs. 6%, p=0.03). Women with postoperative complications more often had transvaginal closure of the vaginal cuff (63% vs. 18%, p<0.001) and continuous sutures (38% vs. 11%, p=0.02) than those without complications. A compensated type of resistance index (RI) of the vaginal branch of the uterine artery was less common in these women than in those without complications (31% vs 70%, p=0.003). That is, the presence of adequate blood flow in the operative zone is, in fact, a protective factor that ensures a complete wound healing process.

Analysis of postoperative period showed that women who developed complications were more likely to have LII≥2 on the third day (50% versus 17%, p=0.008). It should also be noted that women who developed complications in the late postoperative period spent less time in the hospital: the proportion of women whose hospital stay was less than 7 days was higher in women with complications (63% vs 32%, p=0.04).

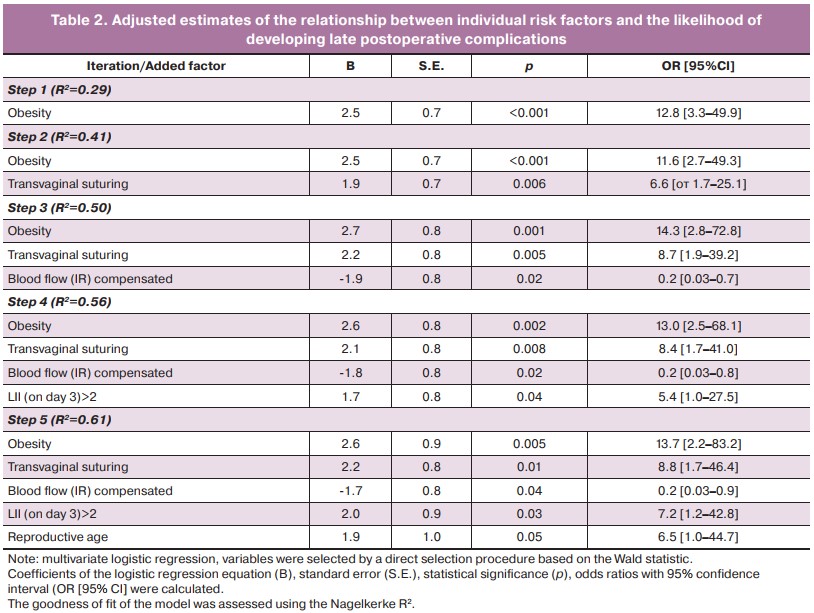

A multivariate analysis was performed to identify the risk factors with the strongest correlation with the risk of postoperative complications (Table 2). The factors most strongly associated with the risk of postoperative complications were obesity, OR=13.7 [95% CI 2.2–83.2], transvaginal closure of the vaginal cuff (versus intracorporeal), OR=8.8 [95% CI 1.7–46.4], LII on day 3 above 2 – OR=7.2 [95% CI 1.2–42.8], patient's reproductive age (compared to premenopausal and postmenopausal) – OR=6.5 [95% CI 1.0–44.7].

Compensated blood flow from the vaginal branch of the uterine artery (compared to the subcompensated, decompensated type or no blood flow) was statistically significant as a protective factor – OR=0.2 [95% CI 0.03–0.9].

Discussion

Despite significant advantages, minimally invasive surgery is not minimal regarding postoperative complications, the incidence of which does not tend to decrease. Complications associated with TLH include bleeding in the early postoperative period, bladder and ureteral injury (0.02–1.7%), formation of vaginal-vaginal fistulas (0.2%), bowel wall injury (0–0.05%), vaginal cuff cellulitis (0.2%), major vessel injury (0.04–0.1%) and VCD with or without evisceration [10].

The incidence of VCD is extremely rare after open and transvaginal hysterectomy, ranging from 0.14 to 4.1%. On the contrary, the incidence of this complication after laparoscopic and robotic total hysterectomy is greater than 5% [11]. In our study, VCD had the highest incidence in patients undergoing TLH. As a rule, VCD occurs after hospital discharge, which requires repeated hospitalization and surgery under general anesthesia (bleeding, vaginal evisceration of bowel loops, peritonitis) [9].

An important component of the risk of VCD is an unfavorable pre-morbid background of the patient, which reduces tissue repair processes. They include smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, immunosuppressed status, and long-term use of corticosteroids [7, 8]. Additionally, monopolar electrocoagulation during colpotomy contributes to the expansion of the necrosis zone and devascularization of the vaginal wall, thus compromising the reparation processes [12]. Combination of several adverse factors makes the risk of complications significant. In turn, the presence of adequate perfusion in the area of the vaginal cuff would guarantee complete healing after surgery, but this discussion of this relationship in the literature is lacking [13]. Meanwhile, the evaluation of the blood flow of the wound margin is effectively used for anastomosis creation in colorectal, plastic, and reconstructive surgery with the intraoperative use of laser angiography and ICG (Indocyanine Green) perfusion [14, 15]. This practice seems extremely useful and requires development and actualization in gynecological surgery [16]. Moreover, in obstetric and gynecological practice, the assessment of blood flow for the prognostic purpose of pregnancy complications (eclampsia, autoimmune diseases, hypertension) is widely used [17].

The uterine artery, being a large branch of the internal iliac artery, supplies blood flow not only to the uterus, but also to some parts of the fallopian tubes and ovaries, and also takes part in the blood supply of the vaginal fornix and bladder [18]. In this regard, in addition to the postoperative assessment of vaginal artery blood flow [19], preoperative duplex scanning will be extremely useful; especially since four anatomo-topographic variants of the uterine artery are known and are likely to be of prognostic value as well [20]. It should be emphasized that difficulties in adequate assessment of uterine artery blood flow are understandable and may require additional examination using contrast-enhanced 3D magnetic resonance angiography [21].

Parameters to evaluate the efficiency of blood supply to the vaginal cuff include the determination of the velocity of blood flow, the resistance index (RI), pulse index (PI) in the uterine artery, and the presence of diastolic nodules (DN). Bilateral changes, as well as the presence of a certain pulse waveform (diastolic nodule) in the uterine arteries, are markers of increased risk of complications [22].

Conclusion

Determination of VCD risk factors after laparoscopic hysterectomy allows for guiding presurgical planning, choosing suturing methods to close the vaginal cuff, and the operative access. For example, refraining from endoscopic intervention in the presence of several adverse factors and choose transvaginal or laparotomy access. In turn, intracorporeal closure of the vaginal cuff should be practiced to a greater extent with laparoscopic access. Besides, identification of risk factors of complications allows for planning the duration of hospital stay after surgery, excluding unreasonable early discharge or, on the contrary, unnecessarily prolonged hospital stay. After discharge from the hospital, this approach makes personalized follow-up of a patient with high risk of VCD in outpatient settings, thus reducing the number of repeated hospitalizations and the associated financial costs.

References

- NHIS National Health Interview Survey, 2008 and 2018 data. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm

- ACOG 2011 Women’s Health Stats.

- Dorsey J.H., Holtz P.M., Griffiths R.I., McGrath M.M., Steinberg E.P. Costs and charges associated with three alternative techniques of hysterectomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996; 335(7): 476-82. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199608153350705.

- Lipscomb G.H. Laparoscopic-assisted hysterectomy: is it ever indicated? Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997; 40(4): 895-902. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00003081-199712000-00025.

- Kilpiö O., Härkki P.S.M., Mentula M.J., Pakarinen P.I. Health-related quality of life after laparoscopic hysterectomy following enhanced recovery after surgery protocol or a conventional recovery protocol. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021; 28(9): 1650-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2021.02.008.

- Uccella S., Ceccaroni M., Cromi A., Malzoni M., Berretta R., De Iaco P. et al. Vaginal cuff dehiscence in a series of 12,398 hysterectomies: effect of differenttypes of colpotomy and vaginal closure. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 120(3): 5l6-23. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e318264f848.

- Croak A.J., Gebhart J.B., Klingele C.J., Schroeder G.., Lee R.A., Podratz K.C. Characteristics of patients with vaginal rupture and evisceration. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004; 103(3): 572-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000115507.26155.45.

- Ceccaroni M., Berretta R., Malzoni M., Scioscia M., Roviglione G., Spagnolo E. et al. Vaginal cuff dehiscence after hysterectomy: a multicenter retrospective study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011; 158(2): 308-13. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.05.013.

- Sterk E., Stonewall K. Vaginal cuff dehiscence – A potential surgical emergency. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020; 38(3): 691.e1-691.e2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.09.013.

- Bezhenar V.F., Tsypurdeeva A.A., Dolinskiy A.K., Bochorishvilli R.G. Laparoscopic hysterectomy – the seven-year experience. Journal of Obstetrics and Women's Diseases. 2011; 60(4): 12-20. (in Russian).

- Kho R.M., Akl M.N., Cornella J.L., Magtibay P.M., Wechter M.E., Magrina J.F. Incidence and characteristics of patients with vaginal cuff dehiscence after robotic procedures. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009; 114(2, Pt1): 231-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e3181af36e3.

- Fanning J., Kesterson J., Davies M., Green J., Penezic L., Vargas R. et al. Effects of electrosurgery and vaginal closure technique on postoperative vaginal cuff dehiscence. JSLS. 2013; 17(3): 414-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.4293/10860813X13693422518515.

- Gurtner G.C., Werner S., Barrandon Y., Longaker M.T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008; 453 (7193): 314-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07039.

- Gurtner G.C., Jones G.E., Neligan P.C., Newman M.I., Phillips B.T., Sacks J.M., Zenn M.R. Intraoperative laser angiography using the SPY system: review of the literature and recommendations for use. Ann. Surg. Innov. Res. 2013; 7(1): 1-14. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1750-1164-7-1.

- Ris F., Hompes R., Cunningham C., Lindsey I., Guy R., Jones O. et al. Near-infrared (NIR) perfusion angiography in minimally invasive colorectal surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2014; 28(7): 2221-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3432-y.

- Beran B.D., Shockley M., Arnolds K., Escobar P., Zimberg S., Sprague M.L. Laser angiography with indocyanine green to assess vaginal cuff perfusion during total laparoscopic hysterectomy: A pilot study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017; 24(3): 432-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2016.12.021.

- Sciscione A.C., Hayes E.J.; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Uterine artery Doppler flow studies in obstetric practice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009; 201(2): 121-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.027.

- Chantalat E., Merigot O., Chaynes P., Lauwers F., Delchier M.C., Rimailho J. Radiological anatomical study of the origin of the uterine artery. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2014; 36(10): 1093-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00276-013-1207-0.

- Shramko S.V., Volkov O.A., Vlasenko A.E., Saltycova P.E. Way to prognosing complications after total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Patent № 2775664 of 06.07.2022. (in Russian).

- Peters A., Stuparich M.A., Mansuria S.M., Lee T.T.M. Anatomic vascular considerations in uterine artery ligation at its origin during laparoscopic hysterectomies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 215(3): 393.e1-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.004.

- Naguib N.N.N., Nour-Eldin N.-E.A., Hammerstingl R.M., Lehnert T., Floeter J., Zangos S., Vogl T.J. Three-dimensional reconstructed contrast-enhanced MR angiography for internal iliac artery branch visualization before uterine artery embolization. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2008; 19(11): 1569-75. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2008.08.012.

- Thaler I., Weiner Z., Itskovitz J. Systolic or diastolic notch in uterine artery blood flow velocity waveforms in hypertensive pregnant patients: relationship to outcome. Obstet. Gynecol. l992; 80(2): 277-82.

Received 06.06.2022

Accepted 30.08.2022

About the Authors

Oleg A.Volkov, MD, Teaching Assistant, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Novokuznetsk State Institute for Advanced Medical Studies, branch of Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education, Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, 654005, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Stroiteley str., 5; Head of Gynecological Department, Group of companies «Mother and Child Siberia», +7(3843)91-07-27, o.volkov@mcclinics.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3271-7167Svetlana V. Shramko, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Novokuznetsk State Institute for Advanced Medical Studies, branch of Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education, Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, 654005, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Stroiteley str., 5, +7(3843)32-47-50, shramko_08@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1299-165Х

Ludmila V. Renge, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Novokuznetsk State Institute for Advanced Medical Studies, branch of Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education, Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, 654005, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Stroiteley str., 5, +7(3843)32-47-50, l.renge@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7237-9721

Polina E. Saltykova, MD, Teaching Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Novokuznetsk State Institute for Advanced Medical Studies, branch of Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education, Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, 654005, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Stroiteley str., 5,

+7(3843)32-47-50, urtica66@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2591-6798

Maxim A. Sabantsev, MD, Head of Gynecological Department, G.P. Kurbatov Novokuznetsk State Clinical Hospital No.1,

654041, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Bardina str., 28, +7(3843)32-45-40, dr.sabantsev@ya.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7104-1852

Evgenia Yu. Shisheya, MD, Head of the Department of Selective Obstetrical and Gynecological Surgery No.1, G.P. Kurbatov Novokuznetsk State Clinical Hospital No.1, 654041, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Bardina str., 28, +7(3843)32-45-40, shisheya@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2296-0873

Elena Yu. Koval, MD, Gynecological Surgeon, G.P. Kurbatov Novokuznetsk State Clinical Hospital No.1, 654041, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Bardina str., 28, +7(3843)32-45-40, covalan@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3025-9550

Anna E. Vlasenko, Specialist at the Department of Medical Statistics and Informatics, Novokuznetsk State Institute for Advanced Medical Studies, branch of Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education, Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, 654005, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Stroiteley str., 5,

+7(3843)32-47-50, vlasenkoanna@inbox.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6454-4216

Ekaterina A. Chubar, Resident at the Gynecological Department, Novokuznetsk State Institute for Advanced Medical Studies, branch of Russian Medical Academy

of Continuous Professional Education, Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, 654005, Russia, Novokuznetsk, Stroiteley str., 5, +7(3843)32-47-50,

ekaterina.chubar.96@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9850-157X

Corresponding author: Oleg A. Volkov, o.volkov@mcclinics.ru

Authors' contributions: Volkov O.A., Shramko S.V., Renge L.V. – manuscript drafting; Volkov O.A., Shramko S.V. – conception and design of the study; Volkov O.A., Saltykova P.E., Sabantsev M.A., Shisheya E.Y., Koval E.Y., Vlasenko A.E., Chubar A.E. –material collection and analysis; Shramko S.V., Renge L.V. – manuscript editing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Novokuznetsk SIAMS, branch of RMACPE, Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Volkov O.A., Shramko S.V., Renge L.V., Saltykova P.E.,

Sabantsev M.A., Shisheya E.Yu., Koval E.Yu., Vlasenko A.E., Chubar E.A.

Complications of laparoscopic hysterectomy: search for risk factors.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 9: 122-128 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.9.122-128