HELLP-синдром остается одним из самых тяжелых осложнений беременности, сопровождающимся поражением печени и других органов. В 1982 году L. Weinstein впервые «отделил» понятие HELLP от преэклампсии [1]. Мировое медицинское сообщество в последующие 34 года далеко продвинулось в изучении HELLP-синдрома. Была разработана целая серия протоколов по диагностике и лечению этого грозного осложнения преэклампсии, появилось несколько теорий и гипотез патогенеза. Но несмотря на то что материнская смертность от HELLP-синдрома за последние десятилетия значительно снизилась, она остается достаточно высокой и в настоящее время варьирует от 0 до 24%, а перинатальная смертность очень высока и составляет 8–60% [2]. При «стертых» (или «невыраженных») клинико-лабораторных проявлениях возникают значительные трудности в диагностике и дифференциальной диагностике с другими заболеваниями, что может коренным образом повлиять на исход.

Аббревиатура «HELLP» описывает характерную клиническую картину, имеющуюся у пациенток с данным синдромом: H – Haemolysis – гемолиз, EL – Elevated Liver enzymes – повышение уровня ферментов печени, LP – Low platelet – низкий уровень тромбоцитов. Однако есть данные о том, что акушеры-гинекологи и реаниматологи в половине случаев имеют дело не с полным HELLP-синдромом, а с частичным, когда имеется лишь один или два компонента, при этом материнские и неонатальные исходы в обоих вариантах течения заболевания практически одинаковые [3]. Для постановки диагноза наличие тромбоцитопении обязательно. Таким образом, в некоторых случаях HELLP-синдром лабораторно может проявиться лишь тромбоцитопенией, что делает дифференциальную диагностику очень сложной, в очередной раз свидетельствует о необходимости и целесообразности междисциплинарного подхода к акушерским пациентам.

HELLP-синдром диагностируется в 0,5–0,9% случаев, в 10–20% осложняет течение тяжелой преэклампсии. Однако, по наблюдениям некоторых авторов, сам по себе HELLP-синдром сочетается с преэклампсией только в 70–80% случаев [4], что ставит под вопрос гипотезу о едином патогенезе этих осложнений беременности, либо это были случаи не HELLP-синдрома, а имитирующих его заболеваний, о которых мы поговорим ниже. В 70% случаев HELLP-синдром развивается до родов с наибольшей частотой между 27-й и 37-й неделями, однако в 10% случаев может развиться до 27-й недели беременности и также в 10% – после 37-й. Соответственно, в 30% наблюдений HELLP-синдром проявляется после родов (в течение 48, реже 72 часов после родов), и в этих случаях вероятность неблагоприятного исхода значительно выше, чаще наблюдаются повреждение почек и отек легких по сравнению с дородовым HELLP-синдромом [5].

Возраст пациенток с HELLP-синдромом больше, чем пациенток с преэклампсией. HELLP-синдром развивается в течение 48 часов после появления протеинурии и гипертензии (в 10–20% случаев отсутствует). Начало, как правило, внезапное. Также факторами риска являются повторные беременности, большая прибавка веса и отеки, которые встречаются у половины пациенток с HELLP-синдромом [2].

Учитывая, что обязательным критерием постановки диагноза «HELLP-синдром» является наличие тромбоцитопении, на наш взгляд наиболее рационально использовать классификацию «Mississippi». I класс: количество тромбоцитов <50×109/л; II класс: количество тромбоцитов <100×109/л; в обоих классах – гемолиз (ЛДГ >600 Ед/л) и повышение уровня АСТ (≥70 Ед/л); III класс: количество тромбоцитов <150×109/л (ЛДГ >600 Ед/л, АСТ ≥40 Ед/л). Авторами, предложившими эту классификацию, выявлены увеличение частоты эклампсии, болей в эпигастрии, тошноты и рвоты, интенсивности протеинурии, частоты материнской заболеваемости и младенческой смертности от III класса к I классу [6].

Наиболее характерными клиническими проявлениями HELLP-синдрома являются боль в правом верхнем квадранте живота, боль в эпигастрии, тошнота и рвота. В 30–60% отмечается головная боль, а 10% отмечают у себя нарушение зрения. Также беременные часто отмечают дискомфорт до появления вышеописанной симптоматики [2].

Далее мы описываем случай развития у пациентки тромбоцитопении в раннем послеродовом периоде и попробуем разобраться в дифференциальном диагнозе по этому синдрому.

Описание клинического наблюдения

Пациентка О., 33 года, поступила в ФГБУ НЦАГиП им. В.И. Кулакова 19.01.2016.

Перенесенные заболевания: ветряная оспа, краснуха, ОРВИ, миопия слабой степени, хронический гепатит С, минимальная вирусная активность с 1998 г. Гинекологические заболевания: эрозия шейки матки в 2006 г. Предыдущие беременности: в 2003 г. – роды своевременные, физиологические – живой мальчик, 4150 г, 55 см; в 2012 г. – роды своевременные, физиологические – живой мальчик, 4200 г, 55 см; в 2015 г. – третья самопроизвольная беременность – данная.

I триместр настоящей беременности протекал без особенностей, пренатальный скрининг был в норме; во II триместре отмечались эпизоды повышения АД до 140 и 90 мм рт. ст. (принимала препарат метилдопа 750 мг/сут.), пренатальный скрининг II триместра – норма; в III триместре диагностирована анемия легкой степени (гемоглобин 102 г/л, получала пероральные препараты железа в рекомендованных дозах), с 36 недели были отмечены отеки кистей рук, протеинурии зафиксировано не было. Общая прибавка в весе за беременность составила 24 кг.

Состояние при поступлении удовлетворительное. Кожные покровы бледно-розовой окраски. Молочные железы мягкие, соски чистые. Живот овальной формы, увеличен в размере за счет беременной матки. Пальпация по ходу вен нижних конечностей безболезненная. Отмечались отеки кистей рук. По органам и системам без особенностей. Масса при поступлении составила 86 кг, рост 170 см, индекс массы тела 30 кг/м2. АД на правой руке 124 и 87 мм рт. ст., на левой – 120 и 80 мм рт. ст., частота сердечных сокращений (ЧСС) 78 в мин.

При поступлении был выставлен диагноз: Беременность 40 недель 3 дня. Головное предлежание. Хронический гепатит С, минимальная вирусная активность. Гестационная артериальная гипертензия. Анемия легкой степени. Отеки беременных.

20.01 в 9:40 пациентка была переведена в родильный блок в связи с развитием регулярной родовой деятельности. Анализы при переводе: Лейкоциты 16,75×109/л, эритроциты 3,91×1012/л, гемоглобин 123 г/л, гематокрит 0,372, тромбоциты 122×109/л, тромбокрит 0,16%, АЧТВ 28,4 сек, протеинурия 0,5 г/л. В 10:15 на высоте одной из потуг в переднем виде затылочного предлежания родилась живая доношенная девочка, без пороков развития. Была оценена по шкале Апгар на 7/8 баллов, масса 3450 г, длина 54 см. В 10:25 самостоятельно отделилась плацента и выделился послед. В 10:30 были выполнены осмотр шейки матки в зеркалах и зашивание разрыва задней спайки. В 11:15 при наружном массаже матки одномоментно выделилось 400 мл жидкой крови со сгустками. Общая кровопотеря в родах была оценена в 650 мл. Проведена терапия: окситоцин 10 МЕ внутривенно капельно, транексамовая кислота 1000 мг внутривенно, раствор кристаллоидов 500 мл внутривенно капельно. В 13:15 была переведена в послеродовую палату.

В 13:30 на консультацию был вызван анестезиолог-реаниматолог в связи с гипотонией и тахикардией у пациентки. При осмотре кожные покровы бледно-розового цвета, частота дыхательных движений (ЧДД) 20/мин, АД 107 и 65 мм рт. ст., ЧСС 98/мин. Был рекомендован клинический анализ крови по cito, назначена инфузия в объеме 500 мл. После получения результатов анализов (лейкоциты 18,28×109/л; гемоглобин 70 г/л; эритроциты 2,24×1012/л; тромбоциты 62×109/л) был установлен мочевой катетер, по которому определялась макрогематурия, в связи с чем пациентка в срочном порядке с диагнозом «Ранний послеродовый период. Анемия тяжелой степени. HELLP-синдром?» была переведена в отделение анестезиологии-реанимации (ОАР).

Общее состояние при поступлении в ОАР средней тяжести. Жалоб не предъявляла. Кожные покровы бледно-розовой окраски. Дыхание везикулярное, хрипов нет, ЧДД 18/мин, SpO2 97%. Гемодинамика: АД 135 и 85 мм рт. ст., ЧСС 90/мин. Матка плотная, выделения – умеренные. По катетеру Фолея моча цвета «мясных помоев». Взяты клинический анализ крови с шизоцитами, общий анализ мочи, биохимический анализ крови с ЛДГ, печеночными ферментами, электролитами, С-реактивный белок, гемостазиограмма с Д-димером. Начато лечение: сульфат магния 25% – 20 мл, внутривенно в течение 20 мин; постоянная инфузия сульфата магния 25% со скоростью 4 мл/ч; дексаметазон 8 мг 3 раза в сутки; преднизолон 500 мг внутривенно в течение часа; нексиум 40 мг 2 раза в сутки; октагам 5 г внутривенно, стерофундин 1500 мл внутривенно, лазикс 40 мг внутривенно. Выполнены катетеризации внутренней яремной вены справа (центральное венозное давление (ЦВД) – отрицательное) и внутренней яремной вены слева. Проведена трансфузия эритроцитарной взвеси в объеме 300 мл. Начат сеанс плазмообмена: общий объем крови 1684 мл, 900 мл плазмы удалено, реинфузия 784 мл эритроцитов, введена донорская свежезамороженная плазма (СЗП) 860 мл. Средний темп диуреза за сутки составил 0,3 мл/кг/час.

В последующие сутки проводилось лечение: магнезиальная терапия (в течение 24 часов), антигипертензивная терапия (метилдопа 250 мг 3 раза в сутки), гормональная терапия, инфузионно-трансфузионная терапия, гастропротекция, иммуномодулирующая терапия (октагам), стимуляция диуреза, антибиотикотерапия, антикоагулянтная терапия (фрагмин 5000 Ед 2 раза в сутки), проведены гемодиафильтрация однократно, 2 сеанса плазмообмена и один сеанс плазмафереза.

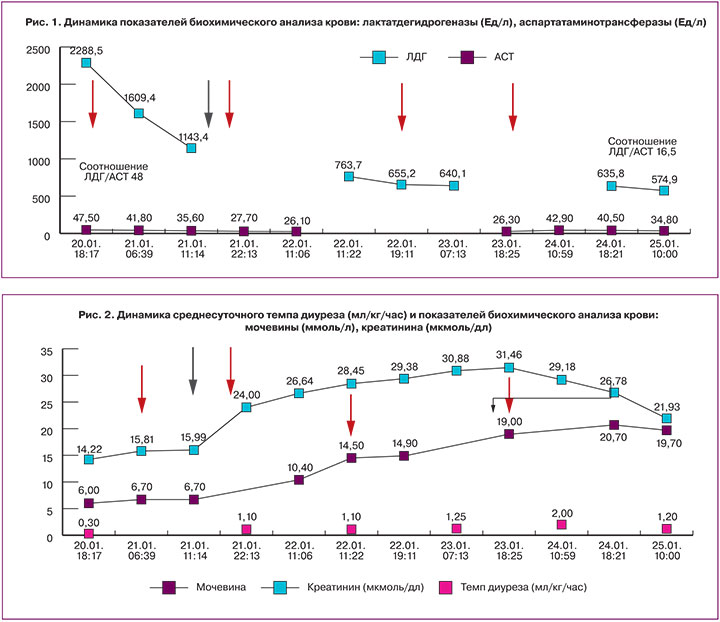

На рис. 1, 2, 3 изображена динамика лабораторных показателей (желтыми стрелками указаны сеансы плазмафереза, серой стрелкой указана процедура гемодиафильтрации).

В первые сутки пациентка отметила субъективное улучшение состояния – «как будто сняли тяжелую плиту с груди и живота».

21.01 была проведена гемодиафильтрация, длительность процедуры составила 6 ч 55 мин, скорость кровотока 250 мл/мин, скорость водообмена 2500 мл/ч, объем ультрафильтрации – 400 мл. Также в этот день был сеанс плазмообмена: общий объем крови 2236 мл, 1000 мл плазмы удалено, реинфузия 1236 мл эритроцитов и введены внутривенно донорская СЗП 1200 мл и стерофундин 400 мл.

После проведения гемодиализа отмечались нормализации показателей свободного гемоглобина и темпа диуреза, который в последующие сутки был не менее 1 мл/кг/ч. Плазмаферез в режиме плазмообмена повлиял на прогрессивное снижение уровня ЛДГ и повышение количества тромбоцитов. Однако нормализация этих показателей происходила не сразу, что заставило задуматься о правомерности диагноза «HELLP-синдром».

21.01 с целью дифференциальной диагностики между аГУС, тромботической тромбоцитопенической пурпурой (ТТП) и HELLP-синдромом были взяты специфические анализы: ADAMTS-13, уровень которого составил 35%, прямая проба Кумбса – положительная. Несмотря на положительную пробу Кумбса, антитела к аутоиммунным заболеваниям со схожей клинической картиной (системная красная волчанка, антифосфолипидный синдром) были в пределах нормативных показателей. Количество шизоцитов в этот день составило 13 на 10 000 эритроцитов. Таким образом, в дальнейшем дифференциальная диагностика в основном проводилась между HELLP-синдромом и аГУС.

22.01 продолжалась интенсивная терапия, был проведен третий сеанс плазмафереза в режиме плазмообмена: общий объем крови 4320 мл, 2000 мл плазмы удалено, реинфузия 2330 мл эритроцитов и введена донорская СЗП 1955 мл и стерофундин 600 мл. Средний темп диуреза за сутки составил 1,1 мл/кг/ч. Гемодинамических и дыхательных расстройств не наблюдалось.

23.01 гемодинамика оставалась стабильная, АД в пределах 110–130 и 75–90 мм рт. ст., ЧСС от 70 до 88/мин. Продолжалась плановая терапия. Выполнен сеанс плазмафереза: объем крови 2142 мл, удалено 1000 мл плазмы, реинфузия 1142 мл эритроцитов, внутривенно введен стерофундин 500 мл. Средний темп диуреза составил 1,25 мл/кг/ч.

В последующие двое суток состояние оставалось стабильным, АД 124 и 79 мм рт. ст., ЧСС 75/мин, ЦВД 9 см вод. ст., ЧДД 16/мин, SpО2 97%, отмечалась относительная нормализация лабораторных показателей, и 25.01 пациентка была переведена в профильное отделение с диагнозом «9-е сутки после своевременных самопроизвольных родов. НЕLLP-синдром. Анемия средней степени. Хронический гепатит С, минимальная вирусная нагрузка».

02.02 пациентка была выписана из стационара. Анализы при выписке: общий белок 64,9 г/л, глюкоза 4,3 ммоль/л, мочевина 6,9 ммоль/л, креатинин 158,3 мкмоль/л, билирубин общий 7,5 мкмоль/л, билирубин прямой 2,1 мкмоль/л, АЛТ 25,8 Ед/л, АСТ 10,9 Ед/л, щелочная фосфатаза 74,7 Ед/л, ЛДГ 448,5 Ед/л, лейкоциты 7,40×109/л, эритроциты 3,12×1012/л, гемоглобин 97 г/л, гематокрит 0,305, тромбоциты 184×109/л, тромбокрит 0,20%, фибриноген 3,33 г/л, протромбиновый индекс 103,2%, МНО 1, АЧТВ 28,6 сек, РКМФ отрицательный, D-димер 2651 мкг/л, общий анализ мочи (pH 7,0, относительная плотность < 1.005, белок отрицательный).

Обсуждение

По данным разных авторов тромбоцитопения во время беременности, в том числе нормально протекающей, встречается в 6–10% [7–9]. При этом в 75–80% случаев гестационная тромбоцитопения встречается изолированно [10].

При обнаружении у пациентки тромбоцитопении, необходимо провести дифференциальную диагностику между HELLP-синдромом и первичными тромботическими микроангиопатиями (ТМА): типичным ГУС (тГУС), ТТП и аГУС [11]. Последние две патологии, а также тяжелый сепсис и острый жировой гепатоз беременных разные авторы нередко называют «имитаторами HELLP-синдрома и/или преэклампсии» [12–14]. В таблице представлена схема проведения дифференциального диагноза HELLP-синдрома с его «имитаторами», предложенная учеными из Франции.

Как видно из представленной таблицы, проведение дифференциального диагноза может вызвать у врачей большие проблемы, особенно аГУС и HELLP-синдрома.

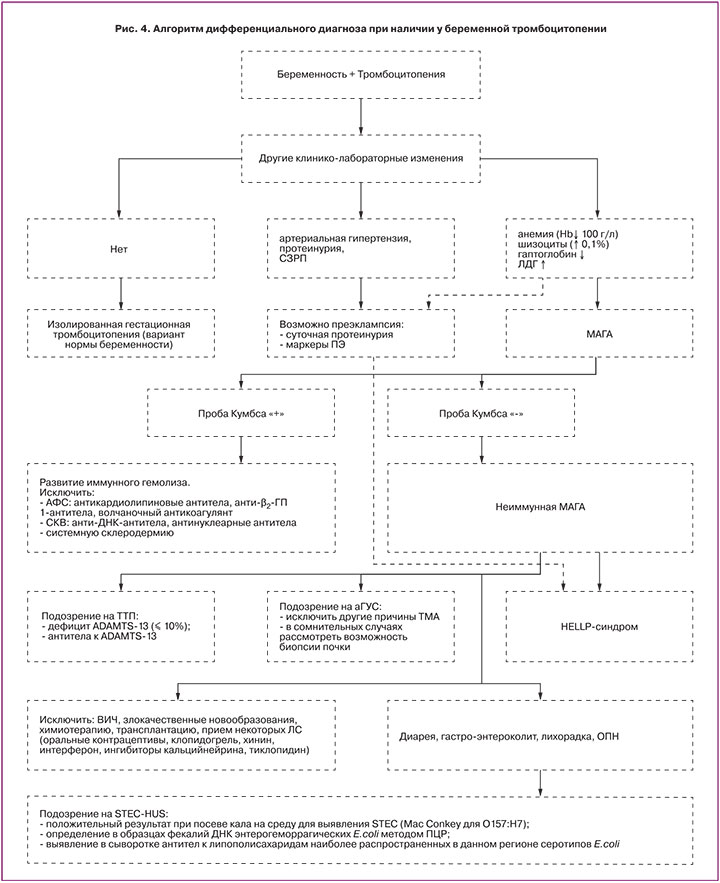

Мы же попробуем провести дифференциальный диагноз по тромбоцитопении и составить его алгоритм, так как именно с клинического анализа крови начинается знакомство врача с лабораторными показателями пациента.

Как уже было сказано, для точной уверенности в диагнозе «HELLP» при смазанной клинической картине, как в демонстрируемом случае, необходимо исключить первичные ТМА. В настоящее время ТМА рассматривают как клинико-морфологический синдром, характеризующий поражение сосудов микроциркуляторного русла. Гистологически ТМА – это особый тип повреждения сосудов, представленный отеком эндотелиальных клеток с их отслойкой от базальной мембраны, расширением субэндотелиального пространства с накоплением в нем аморфного мембраноподобного материала и образованием тромбов, содержащих тромбоциты и фибрин, что приводит к окклюзии просвета сосуда, вызывая развитие ишемии органов и тканей. Клинически ТМА проявляется тромбоцитопенией, развивающейся вследствие потребления тромбоцитов в процессах распространенного тромбообразования, микроангиопатической гемолитической Кумбс-негативной анемией (МАГА), лихорадкой и поражением различных органов, главным образом, почек и центральной нервной системы. Таким образом, клиническая картина ТМА состоит из классической триады: тромбоцитопении, МАГА и острого повреждения почек. Первичные ТМА включают в себя ТТП, тГУС и аГУС, этиология и патогенез которых установлены [15]. Также гематологи и нефрологи из разных стран мира выделяют патологические состояния, которые сами по себе могут приводить к ТМА (вторичная ТМА): преэклампсия, эклампсия, HELLP-синдром; инфекции: ВИЧ, грипп H1N1, сепсис; лекарственная терапия: хинин, интерферон, ингибиторы кальцинейрина (циклоспорин, такролимус), ингибиторы mTOR (сиролимус, эверолимус), противоопухолевые препараты (цисплатин, гемцитабин, митомицин, ингибиторы сосудисто-эндотелиального фактора роста и тирозинкиназы – бевацизумаб, сунитиниб, сорафениб), оральные контрацептивы, валацикловир; другие заболевания: метилмалоновая ацидурия с гомоцистеинурией, злокачественная артериальная гипертензия, злокачественные опухоли, ионизирующее излучение, трансплантация солидных органов и костного мозга; аутоиммунные заболевания, такие как системная красная волчанка, системная склеродермия, антифосфолипидный синдром, гломерулопатии, в связи с чем при наличии у пациента гемолиза необходимо исключить его иммунную природу [15–17]. Учитывая вышесказанное, все чаще появляются попытки применять при лечении HELLP-синдрома экулизумаб (применяемый для лечения аГУС) – рекомбинантное гуманизированное моноклональное антитело класса IgG к С5 компоненту комплемента – в качестве дополняющей терапии, c получением хороших результатов [18].

Принимая во внимание тот факт, что HELLP-синдром относят к вторичным ТМА, логично было бы предположить, что морфологические изменения в тканях при HELLP-синдроме и первичными ТМА будут практически одинаковыми. Патологи из Гамбурга провели аутопсию органов трех женщин, умерших от HELLP-синдрома, и подробно описали изменения в них. У первой женщины в почках определялись бескровные клубочки с набухшими и вакуолизированными интракапиллярными клетками, грыжи из капиллярных петель в проксимальных извитых канальцах и набухшие мезангиальные клетки; в клубочковых капиллярах и сосудах мозгового слоя тромбообразование наблюдалось нечасто. Во втором случае клубочки почки также были бескровные, с растянутыми сигарообразными петлями, также отмечена интракапиллярная вакуолизация. В последнем случае в почках снова определялись удлиненные бескровные капиллярные петли с вакуолизацией интракапиллярных клеток, а также увеличенные клубочки, грыжа петли Боумена в проксимальных извитых канальцах и набухание мезангиальных клеток. Таким образом, тромбы определялись только в первом случае и были редки. В печени исследуемых была следующая картина: перипортальный гепатоцеллюлярный некроз (коагуляционный некроз); кровоизлияния от окружающей непораженной паренхимы печени резко разграничены широкой сетью фибрина; в синусоидах печени отмечен фокальный лимфостаз, набухание клеток Купфера и застой желчи; отсутствие воспалительных клеточных инфильтратов в печеночной ткани и жировой трансформации гепатоцитов [19].

Описанная патологами картина несколько не соответствует морфологической картине, наблюдаемой при ТМА. Также отечественными учеными выполнен анализ и патоморфологические исследования 8 случаев смерти от преэклампсии и эклампсии, в котором описанные изменения в почках не очень похожи на изменения в почках при ТМА [20]. Все это позволяет говорить о том, что именно сам HELLP-синдром вызывает изменения в организме, которые похожи на ТМА, а не является вторичной ТМА. Случай аутопсии, проведенной исследователями из Гамбурга, при которой в почках определялись тромбы, скорее указывает на далеко зашедший HELLP с уже начавшийся ТМА, в остальных же случаях, видимо, ТМА развиться не успела.

Типичный ГУС – это заболевание, при котором на фоне диареи, вызванной Shiga toxin, продуцирующей Escherichia coli (STEC), в основном серотипом O157:H7, развивается неиммунная МАГА, тромбоцитопения и острая почечная недостаточность [21]. Типичный ГУС у данной пациентки был исключен, так как не было факторов риска его развития (возраст от 6 месяцев до 5 лет, гемоколит, лихорадка, рвота), характерного анамнеза (часто возникает вследствие желудочно-кишечной инфекции, сначала возникает диарея, затем гемоколит), типичных симптомов (диарея, тошнота, рвота, боль в животе, гастроэнтероколит) [22], а авторы из Японии наблюдали энцефалопатию у 62% своих пациентов с тГУС [23], чего также не было отмечено у пациентки.

ТТП – это редкое, потенциально смертельное заболевание крови, характеризующееся развитием ТМА вследствие снижения активности в крови металлопротеиназы, именуемой ADAMTS-13, которая участвует в регуляции размера фактора Виллебранда, основного модулятора адгезии и агрегации тромбоцитов в микроциркуляторном русле [24]. Наследственная форма ТТП (синдром Апшоу–Шульмана) обусловлена генетическим дефектом ADAMTS-13, а приобретенная форма ТТП обусловлена формированием антител к ADAMTS-13 или к ее ингибитору [25].

У пациентов с врожденными ТТП определяется тяжелый дефицит ADAMTS-13 (<10%, при норме 80–110%), однако у пациентов с приобретенной ТТП может быть клинико-лабораторная гетерогенность и не всегда есть острый дефицит ADAMTS-13 [24]. В связи с этим важно определять не только дефицит ADAMTS-13, но и антитела к ADAMTS-13, особенно если его активность несколько снижена, но не критична. Также крайне важно иметь в виду тот факт, что с помощью плазмафереза удаляется большой объем плазмы пациента, содержащей антитела ADAMTS13 (или не содержащей, в случае наследственной формы ТТП), и заменяется донорской плазмой (в случае режима плазмообмена) с нормальной активностью ADAMTS13 [26]. Именно поэтому крайне важно взять кровь у пациента до начала трансфузии донорской СЗП, однако отсутствие возможности определения активности ADAMTS-13 не должно отсрочить начало лечения [16, 27]. Случай с нашей пациенткой именно такой: активность ADAMTS-13 у нее составила 35%, однако анализ, к сожалению, был взят после сеанса плазмообмена, более того, не были взяты антитела к ADAMTS-13.

аГУС – орфанное (2–7 случаев на 1 000 000), хроническое системное заболевание генетической природы, в основе которого лежит неконтролируемая активация альтернативного пути комплемента, ведущая к генерализованному тромбообразованию в сосудах микроциркуляторного русла (комплемент-опосредованная ТМА) [15]. Патогенез аГУС не связан с Shiga toxin, частота составляет около 5–10% всех случаев ГУС [28]. Центральное место в патогенезе аГУС занимает неконтролируемая активация альтернативного пути комплемента и нарушение его регуляции, в результате чего повреждается эндотелий с последующим образованием тромбов. Снижение уровня С3 компонента комплемента и нормальный уровень С4 свидетельствуют об активации альтернативного пути комплемента и подтверждает диагноз (нормальные же показатели не исключают диагноз аГУС) [29]. К сожалению, снижение уровня С3 не является основанием для исключения ТТП [30]. Таким образом, диагноз ставится после исключения других первичных ТМА. аГУС проявляется триадой симптомов (триадой ТМА): механической или неиммунной (отрицательная проба Кумбса, кроме ложно-положительного теста при Streptococcus pneumoniae-индуцированном ГУС) гемолитической анемией (гемоглобин <100 150="" 000="" 103="" -="" 31="" 15="" -="" 32="" p="">

У демонстрируемой пациентки, скорее всего, при поступлении уже была преэклампсия (протеинурия, отеки, артериальная гипертензия), что свидетельствовало в пользу HELLP-синдрома, несмотря на отсутствие преждевременных родов и задержки развития плода, так как исходы беременности у пациенток с преэклампсией в сравнении с беременными без артериальной гипертензии характеризуются большей частотой преждевременных родов и более низкими весо-ростовыми показателями новорожденных [33]. Удалось исключить тГУС, ТТП и иммунные причины развития гемолитической анемии. И несмотря на то, что в течение сеансов экстракорпоральных методов гемокоррекции отмечалась положительная динамика уровня тромбоцитов, ЛДГ и АСТ, продолжался рост креатинина и мочевины на фоне адекватного темпа диуреза. Данный факт позволил усомниться в диагнозе HELLP-синдром и задуматься над диагнозом аГУС и возможностью введения экулизумаба. Однако после четвертого сеанса плазмафереза началась тенденция к нормализации показателей креатинина и мочевины и через неделю уровни этих показателей составляли соответственно 158,3 мкмоль/л и 6,9 ммоль/л.

Исходя из вышеизложенного, мы предлагаем алгоритм дифференциального диагноза при наличии у беременной тромбоцитопении (рис. 4).