International and Russian experience in monitoring maternal near-miss cases

Murashko M.A., Sukhikh G.T., Pugachev P.S., Filippov O.S., Artemova O.R., Sheshko E.L., Pryalukhin I.A., Gasnikov K.V.

Maternal mortality is a critical indicator to assess the quality of services provided by a health care system as a whole. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recently recommended investigating severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and near-miss cases as a benchmark practice for monitoring maternal healthcare. The present review outlines the methodological framework for managing severe maternal morbidity case records and gives a comprehensive overview of SMM surveillance systems in Brazil, the United States of America, New Zealand, Canada, Europe, China, and the Russian Federation.

The main differences of the SMM surveillance system implemented in the Russian Federation are a) the SMM surveillance system provides real-time coverage of all medical organizations in all the country's regions; b) SMM cases and maternal deaths are recorded in a single register; c) 24-hour monitoring is conducted by the largest national obstetric and gynecological institution; d) immediate consultations by the country's leading experts in obstetrics, gynecology, and obstetric anesthesia are available for all SMM cases through telemedicine technologies.

Conclusion. A unique national surveillance system for severe maternal morbidity has been implemented in the Russian Federation.

Keywords

Maternal mortality characterizes the availability and quality of obstetric services and is an essential general indicator of health system performance regarding quality and accessibility of appropriate care [1]. Proper reporting of every maternal death is necessary to understand their direct causes and develop evidence-based interventions to prevent maternal mortality.

The World Health Organization has recommended investigating near-misses as a benchmark practice for monitoring maternal healthcare and has standardized the criteria for diagnosis

The World Health Organization has proposed several approaches to investigating maternal death's causes and risk factors, including a confidential investigation of maternal deaths at the national level. However, recently WHO has recommended that developed countries with low maternal mortality investigate near-misses as a benchmark practice for monitoring maternal healthcare [2].

Definitions

Maternal death is the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, and can stem from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes [3].

Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) includes diseases, syndromes, and symptoms that require resuscitation and intensive care for women during pregnancy and within 42 days after pregnancy termination [4].

WHO recommends using the term "maternal near-miss" [5].

In the USA and Canada, maternal near-miss is commonly referred to as severe maternal morbidity [6]. Approaches to the definition and monitoring SMM worldwide differ significantly in different countries and within one country, and even in medical organizations in the same city.

Next, we will overview the main approaches to identifying and monitoring SMM in different countries.

World Health Organization (WHO)

In 2009, the WHO defined a near miss as a woman who nearly died but survived a complication during pregnancy, childbirth, or within 42 days of pregnancy termination [7]. In a practical sense, this is a woman's survival in a near-miss case [5].

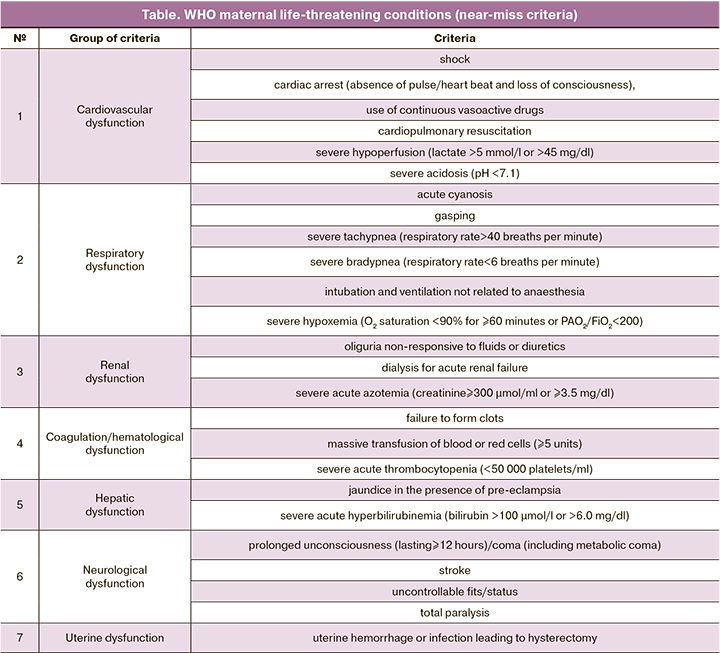

The WHO criteria for maternal life-threatening conditions (near-miss criteria) are presented in the table.

WHO recommends that countries develop local protocols based on these criteria taking into consideration regional characteristics. To standardize approaches to assessing SMM, adding new items to the near-miss criteria is not recommended. Using these criteria, the near-miss rate is generally expected to be around 7.5 cases/1000 deliveries [5]. The projected number of SMM using the WHO methodology and criteria in the Russian Federation expected to be about 11,000 annual cases.

In 2011–2018 there has been an increased interest in maternal SMM in Africa and Asia countries, with many studies estimating their SMM burden. Most of them used the WHO criteria. SMM in the studies ranged from 4.3 (Lebanon) to 198 (Nigeria) per 1000 live births. The leading reason for identifying cases as SMM in each study was obstetric hemorrhage [8].

In 2016, the WHO Regional Office for Europe published a manual with practical tools for conducting a maternal near-miss case review cycle at the hospital level. The document explains how effectively implement the individual near-miss case review (NMCR) cycle at the international level, within the country, and the medical organization. The near-miss case review's primary purpose is to reduce preventable maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Audit using the WHO identification criteria for maternal near-miss cases has been implemented in 13 countries of Eurasia [9].

Brazil

In 2012, a prospective study using the World Health Organization's criteria for SMM and maternal near-miss was conducted in Brazil. The study involved 27 referral maternity hospitals from all regions of Brazil. Near-miss cases were identified among 82 388 delivering women over one year; 82 144 children were born alive. Among 9555 near-miss cases, there were 140 deaths and 770 maternal near-miss cases (9.3 per 1000 live births). The ratio of maternal deaths to near-miss cases was 1:5.5 [10].

In the past 35 years, there has been a significant increase in the U.S. maternal mortality rate from 7.2 in 1986 [11] to 17.4 per 100 000 live births in 2018 (in the U.S., late maternal death is included in maternal mortality) [12]. In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) began monitoring severe maternal morbidity based on 25 indicators [13]. In 2015, the list was reduced to 21 indicators [14], including acute myocardial infarction, aneurysm, acute renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, amniotic fluid embolism, cardiac arrest/ ventricular fibrillation, conversion of cardiac rhythm, disseminated intravascular coagulation, eclampsia, heart failure/arrest during surgery or procedure, puerperal cerebrovascular disorders, pulmonary edema/ acute heart failure, severe anesthesia complications, sepsis, shock, air and thrombotic embolism, blood products transfusion, hysterectomy, temporary tracheostomy, and ventilation. All severe morbidity indicators were presented with corresponding ICD-10 codes.

The rates of severe maternal morbidity in the United States are calculated as the number of deliveries involving severe maternal morbidity per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations; it tends to increase (from 49.5 in 1993 to 144.0 in 2014). The most common indicator of severe maternal morbidity in the U.S. was blood transfusion representing a fivefold increase (from 24.5 to 122.3 per 10,000 births) during ten years [15]. For every pregnancy-related death, there are approximately 70 cases of severe maternal morbidity [12].

If we apply the U.S. approach to estimating SMM incidence rate in the Russian Federation, it would be about 21,000 annual cases.

A more straightforward two-factor approach has been used within Illinois and in some California clinics, where severe maternal morbidity was identified as any intensive or critical care unit admission and/or four or more units of packed red blood cells transfused at any time from conception through 42 days postpartum [16, 17].

New Zealand

The country adopted the Illinois model of SMM identification as any intensive care or high-dependency unit admission (not considering packed red blood cells transfusion). The national rate of women with severe maternal morbidity admitted to intensive or high-dependency units was 6.2 per 1000 live births [8].

Canada

Currently, Canada has no national severe maternal morbidity surveillance system and maternal mortality reduction targets [18].

EURO-PERISTAT

EURO-PERISTAT, a collaboration of 31 European countries focused on developing perinatal health indicators, defined severe maternal morbidity as a composite of the rates of eclampsia, hysterectomy for postpartum hemorrhage, admission to intensive or critical care unit, blood transfusion, and uterine artery embolization.

The central problem encountered by researchers was that only three countries (France, Germany, and the Netherlands) provided data about all indicators. Researchers reported that the percentage of severe maternal morbidity underestimation ranges from 20% in France to 87% in Slovenia.

According to EURO-PERISTAT, the severe maternal morbidity rate in France, Germany, and the Netherlands was 4.3, 15.5, and 9.9 per 1000 live births, respectively. The most and least common indicators were blood transfusion and uterine artery embolization, respectively [19].

United Kingdom

In addition to EURO-PERISTAT reports, in the UK, cases of severe maternal morbidity are monitored by the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) [20]. In contrast to the mandatory 1952 Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD) [21], maternity hospitals' UKOSS program participation is voluntary. UKOSS identifies near-miss cases through routine monthly mailing reporting cards to maternity units in the UK. An average of 93% of cards is returned each month [22]. The UKOSS system summarizes data on the conditions, including acute fatty liver, amniotic fluid embolism, pulmonary embolism in pregnant women, eclampsia, peripartum hysterectomy, and tuberculosis during pregnancy. The list is not strictly regulated and changes annually, so it is difficult to obtain statistics on the total severe maternal morbidity. Additionally, the UKOSS has been used to conduct studies on other clinical conditions, such as H1N1 influenza in pregnant women in 2009 [23]; obstetric sepsis in 2012 [24]; new coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in pregnancy in 2019 [25], and others.

China

In China, National Maternal Near Miss Surveillance System (NMNMSS) was established at the end of 2010 and is funded by the National Health Commission. Methodological support is provided by WHO [26]. The surveillance sites in the NMNMSS cover nearly 13% of China's population (over 182 million people) [27]. Near-miss cases are defined by WHO criteria.

Once the near-miss criteria are identified, data are entered by trained midwives or obstetricians-gynecologists onto a web-based online centralized reporting system. A retrospective analysis of data entry quality is carried out twice a year at the district level and annually at municipal, regional, and national levels. At the national level, monitoring is carried out by specialists from the National Office for Maternal and Child Health Surveillance of China through inspections in 6–8 medical organizations from 6 randomly selected provinces. If inconsistencies are identified beyond specific criteria (for example, underestimating pregnancy complications by more than 5% or underestimating maternal deaths by more than 1%), medical organizations recheck the data entered in the surveillance system and correct the identified errors. In 2017, the surveillance system registered 37,060 near-miss cases and 968 maternal deaths.

The ratio of maternal deaths to near-miss cases in China is 1:38 [26].

The leading organ dysfunction for inclusion in a maternal near-miss in China is blood coagulation disorders caused by obstetric bleeding [28].

Russian Federation

According to Form No. 32 (line No. 7 of the insert), SMM statistics in the Russian Federation include uterine rupture, eclampsia, severe preeclampsia, postpartum sepsis, postpartum infection, bleeding during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Of course, this list does not cover all possible causes of SMM.

In 2015, as part of an all-Russian audit of near-miss cases (life-threatening maternal conditions without fatal outcome), the Department of Child’s Health Care and Maternity Services revised the near-miss identification criteria, dividing them into laboratory criteria [PaO2/FiO2< 200 mmHg, creatinine ≥3.5 mg/ dL (308 μmol/L); total bilirubin> 6.0 mg/dL (102 μmol/L), acidosis (pH <7.1), platelet count< 50,000] and patient management criteria (use of vasoactive drugs, hysterectomy, blood transfusion, mechanical ventilation ≥ 1 hour, hemodialysis, cardiopulmonary resuscitation) [29]. Since 2016, SMM audit has been conducted annually. According to the 2016 audit, the ratio of maternal death to near-miss cases was 1:16 [30].

Until 2021, there were no mandatory uniform identification criteria for SMM cases in the Russian Federation. This situation led to significant discrepancies in statistical reporting. For example, according to the results of the 2018 audit, SMM rates in two regions from the same federal district could be more than thirtyfold different (8.8 and 0.25 cases per 1000 births in Nenets Autonomous Okrug and St. Petersburg, respectively). In some regions, the number of SMM cases was equal to the number of maternal deaths (Chechen Republic) [31].

On January 18, 2021, the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation adopted the Regulation for SMM Surveillance (from now on referred to as the Regulation).

The Regulation defines SMM cases as diseases, syndromes, and symptoms that require resuscitation and intensive care for women during pregnancy and within 42 days after its termination.

On February 01, 2021, the All-Russian Register for SMM Surveillance was put into operation. It functions using a specialized vertically integrated medical information system Obstetrics and Gynecology and Neonatology (Akusherstvo I Ginekologiya I Neonatologiya – AKiNEO) of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (from now on VIMIS AKiNEO). V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation monitors all SMM cases in the Russian Federation using the VIMIS AKiNEO patient monitoring subsystem and the SMM Register.

The Regulation defines identification criteria for entry into the Register, including the presence of conditions and diseases, syndromes, and symptoms that require resuscitation and intensive care for women during pregnancy, childbirth, and in the postpartum period under the Procedure for the provision of medical care in the field of obstetrics and gynecology, approved by order of the Ministry of Health of Russia No. 1130-n dated October 20, 2020. This list represents modified WHO near-miss identification criteria.

Employees of remote consulting centers in the regions of the Russian Federation [32] enter SMM case data into the Register. Some Russian regions followed the example of the Register and established regional remote consulting centers, organized the redistribution of information flows about SMM cases to maternity hospitals of the IIIA group from regional centers for disaster medicine or multidisciplinary hospitals, and developed regional regulations on the functioning of obstetric remote consulting centers, staffed with obstetricians-gynecologists, anesthesiologists and critical care specialists.

The Regulations define a list of 12 criteria requiring a telemedicine consultation with the specialists of the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. The criteria include cardiac arrest (cardiopulmonary resuscitation), eclampsia, preeclampsia complicated by deep jaundice, acute fatty liver, thrombotic microangiopathy, HELLP syndrome, aHUS, TTP, APS, hemorrhagic, anaphylactic, cardiogenic shock, resistant to therapy, adult acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary edema (any etiology), massive blood loss and/or ongoing bleeding, sepsis or severe systemic infection, septic shock, massive pulmonary embolism, decompensation of somatic pathology (any), other life-threatening conditions in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum, identified by specialists from regional obstetric distance centers.

The moment of discontinuation of remote monitoring of a patient with SMM in V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation is the patient discharge from the intensive care unit (transfer to a specialized department, discharge from a medical organization for outpatient follow-up or death). Remote monitoring continues in extremely severe cases and in patients who lack clinically significant improvement or need telemedicine consultation.

To ensure 24-hour SMM monitoring, the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P established a duty service staffed with skilled obstetricians-gynecologists and anesthesiologists. The service works closely with the telemedicine department. In the future, it is planned to switch from manual data entry to filling the Register automatically based on primary data transmitted in the form of structured electronic medical documents.

In addition to SMM cases, the Register keeps records of all maternal deaths in real-time. Information is entered into the Register no later than 24 hours after receiving the initial report on maternal death.

To further improve approaches to critical conditions (near-miss) analysis and maternal mortality, the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation issued a letter on March 11, 2021, with the rules for conducting annual audits of SMM [33].

Conclusion

SMM identification criteria for including in the Register are based on modified WHO and US recommendations (using the need for resuscitation or intensive care as an additional mandatory criterion). The system for SMM surveillance implemented in the Russian Federation is unique in world practice since the system not only registers SMM cases but also monitors the patient's condition in real-time with complete coverage of the whole country and the ability to optimize patients' management using telemedicine consultations with leading experts of the country’s largest national obstetric and gynecological institution (V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation).

References

- Callaghan W.M. Maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018; 61(2): 294-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000376.

- Материнская смертность в Российской Федерации: анализ официальных данных и результаты конфиденциального аудита в 2013 году. Методическое письмо Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 2 октября 2014 года №15-4/2-7509. [Maternal mortality in the Russian Federation: official data analysis and results of a confidential audit in 2013. Methodological letter of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 2014. (in Russian)].

- Приказ Министерства здравоохранения и социального развития Российской Федерации от 23 июня 2006 года № 500 «О совершенствовании учета и анализа случаев материнской смерти в Российской Федерации». [Order of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation No. 500 of June 23, 2006 "On Improving the Accounting and Analysis of Maternal Deaths in the Russian Federation". (in Russian)].

- Регламент мониторинга критических акушерских состояний в Российской Федерации. Письмо Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 18 января 2021 года № 15-4/66. [Regulations for monitoring critical obstetric conditions in the Russian Federation. Letter No. 15-4/66 of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation dated January 18, 2021. (in Russian)].

- Evaluating the quality of care for severe pregnancy complications. The WHO near-miss approach for maternal health. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services; 2011. 29p.

- England N., Madill J., Metcalfe A., Magee L., Cooper S., Salmon C., Adhikari K. Monitoring maternal near miss/severe maternal morbidity: A systematic review of global practices. PLoS One. 2020; 15(5): e0233697. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233697.

- Pattinson R., Say L., Souza J.P., van den Broek N., Rooney C. WHO maternal death and near-miss classifications. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009; 87(10): 734. https://dx.doi.org/10.2471/blt.09.071001.

- Geller S.E., Koch A.R., Garland C.E., MacDonald E.J., Storey F., Lawton B. A global view of severe maternal morbidity: moving beyond maternal mortality. Reprod. Health. 2018; 15(Suppl. 1): 98. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0527-2.

- Conducting a maternal near-miss case review cycle (NMCR) at hospital level: Manual with practical tools. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2016. 94p.

- Cecatti J.G., Costa M.L., Haddad S.M., Parpinelli M.A., Souza J.P., Sousa M.H. et al. Network for Surveillance of Severe Maternal Morbidity: a powerful national collaboration generating data on maternal health outcomes and care. BJOG. 2016; 123(6): 946-53. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13614.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm.

- Ahn R., Gonzalez G.P., Anderson B. Initiatives to reduce maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity in the United States: A narrative review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020; 173(11, Suppl.): S3-10. https://dx.doi.org/10.7326/M19-3258.

- Callaghan W.M., Creanga A.A., Kuklina E.V. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 120(5): 1029-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. Severe maternal morbidity. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/smm/severe-morbidity-ICD.htm

- Fingar K.R., Hambrick M.M., Heslin K.C., Moore J.E. Trends and disparities in delivery hospitalizations involving severe maternal morbidity 2006-2015: Statistical brief No. 243. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 4 2018.

- Ozimek J.A., Eddins R.M., Greene N., Karagyozyan D., Pak S., Wong M., Zakowski M., Kilpatrick S.J. Opportunities for improvement in care among women with severe maternal morbidity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 215(4): 509. e1-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.022.

- Koch A.R., Roesch P.T., Garland C.E., Geller S.E. Implementing statewide severe maternal morbidity review: the Illinois experience. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2018; 24(5): 458-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000752.

- Cook J.L., Majd M., Blake J., Barrett J.Y., Bouvet S., Janssen P. et al. Measuring maternal mortality and morbidity in Canada. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017; 39(11): 1028-37. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2017.06.021.

- Bouvier-Colle M.H., Mohangoo A.D., Gissler M., Novak-Antolic Z., Vutuc C., Szamotulska K., Zeitlin J.; Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee. What about the mothers? An analysis of maternal mortality and morbidity in perinatal health surveillance systems in Europe. BJOG. 2012; 119(7): 880-90. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03330.x.

- Knight M., Lindquist A. The UK Obstetric Surveillance System: impact on patient safety. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013; 27(4): 621-30. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.03.002.

- Lucas D.N., Bamber J.H. UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths – still learning to save mothers' lives. Anaesthesia. 2018; 73(4): 416-20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/anae.14246.

- Knight M., Lewis G., Acosta C.D., Kurinczuk J.J. Maternal near-miss case reviews: the UK approach. BJOG. 2014; 121(Suppl. 4): 112-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12802.

- Knight M., Brocklehurst P., O’Brien P., Quigley M.A., Kurinczuk J.J. Planning for a cohort study to investigate the impact and management of influenza in pregnancy in a future pandemic. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015.

- Acosta C., Kurinczuk J., Lucas D., Sellers S., Knight M. Incidence, causes and outcomes of severe maternal sepsis morbidity in the UK. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013; 98(Suppl. 1): A2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-303966.004.

- Magee L.A., Khalil A., von Dadelszen P. Covid-19: UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) study in context. BMJ. 2020 Jul 27; 370: m2915. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2915.

- Mu Y., Wang X., Li X., Liu Z., Li M., Wang Y. et al. The national maternal near miss surveillance in China: A facility-based surveillance system covered 30 provinces. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98(44): e17679. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017679.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available at: http://data.stats.gov.cn/english/easyquery.htm?cn=C01

- Ma Y.Y., Zhang L.S., Wang X., Qiu L., Hesketh T., Wang X. Low incidence of maternal near-miss in Zhejiang, a Developed Chinese Province: A cross-sectional study using the WHO approach. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020; 12: 405-14. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S243414.

- Письмо Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 11 декабря 2015 года № 15-4/4370-07. [Letter of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 15-4/4370-07 dated 11 December 2015. (in Russian)].

- Пырегов А.В., Шмаков Р.Г., Федорова Т.А., Юрова М.В., Рогачевский О.В., Грищук К.И., Стрельникова Е.В. Критические состояния «near-miss» в акушерстве: трудности диагностики и терапии. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 3: 228-37. [Pyregov A.V., Shmakov R.G., Fedorova T.A., Yurova M.V., Rogachevsky O.V., Grischuk K.I., Strelnikova E.V. "Near-miss" critical conditions in obstetrics: difficulties of diagnosis and therapy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; 3: 228-37. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.228-237.

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации, Департамент медицинской помощи детям и службы родовспоможения. Аудит критических акушерских состояний в Российской Федерации в 2018 году. Методическое письмо. М.; 2019. [Critical obstetric conditions audit in the Russian Federation in 2016. Methodological letter of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 2019. (in Russian)].

- Мурашко М.А. Дистанционный консультативный центр – оперативный контроль над оказанием акушерской помощи в регионе. Журнал акушерства и женских болезней. 2004; 2: 44-7. [Murashko M.A. The remote consulting centre – operative control for rendering obstetric care in Komi Republic. Journal of Obstetrics and Women's Diseases. 2004; 2: 44-7. (in Russian)].

- О методических подходах к оценке и анализу критических состояний (near miss) на основании критериев ВОЗ. Письмо Министерства здравоохранения Российской Федерации от 11 марта 2021 года № 15-4/383. [Methodological approaches to the assessment and analysis of critical conditions (near miss) based on WHO criteria. Letter of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 15-4/383 dated 11 March 2021. (in Russian)].

Received 11.03.2021

Accepted 19.03.2021

About the Authors

Mikhail A. Murashko, Dr. Med. Sci., Minister of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)628-44-53. E-mail: info@rosminzdrav.ru.

127994, Russia, Moscow, Rakhmanovsky per., 3.

Gennady T. Sukhikh, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Director of V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)438-18-00. E-mail: g_sukhikh@oparina4.ru.

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Pavel S. Pugachev, Deputy Minister of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)628-44-53. E-mail: info@rosminzdrav.ru.

127994, Russia, Moscow, Rakhmanovsky per., 3.

Oleg S. Filippov, Dr. Med. Sci., Deputy Director of the Department of Child’s Health Care and Maternity Services, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)627-24-00 (ex. 1503). E-mail: FilippovOS@rosminzdrav.ru. ORCID: 0000-0003-2654-1334.

127994, Russia, Moscow, Rakhmanovsky per., 3.

Oliya R. Artemova, Deputy Director of Digital Development and Information Technology Department, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)627-24-00 (ex. 1801). Е-mail: ArtemovaOR@minzdrav.gov.ru. ORCID: 0000-0001-6472-6036.

127994, Russia, Moscow, Rakhmanovsky per., 3.

Elena L. Sheshko, Ph.D., Head of the Project Management Department, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)531-44-44 (ext. 1113). E-mail: e_sheshko@oparina4.ru.

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Ivan A. Prialukhin, Ph.D., Head of Project Methodology Department, Project Organization Department, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)531-44-44 (ex. 3143). E-mail: i_prialukhin@oparina4.ru.

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Kirill V. Gasnikov, Ph.D., Head of Project Administration, Project Management Department, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)531-44-44 (ex. 3140). E-mail: k_gasnikov@oparina4.ru.

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

For citation: Murasnko M.A., Sukhikh G.T., Pugachev P.S., Filippov O.S., Artemova O.R., Sheshko E.L., Pryalukhin I.A., Gasnikov K.V. International and Russian experience in monitoring maternal near-miss cases.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya / Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021; 3: 5-11 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.3.5-11