Clinical and anamnestic factors and lifestyle features significantly influencing apical prolapse

Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S., Matskevich E.N., Babicheva I.A.

Objective: To evaluate lifestyle features and significant clinical and anamnestic factors associated with apical prolapse in parous women.

Materials and methods: A clinical retrospective case-control study analyzed medical records data of 230 patients with pelvic organ prolapse who underwent examination and treatment in the period from 2017 to 2024 at the University Clinic "I am healthy!" The main group was composed of 130 patients with apical prolapse, and the control group was composed of 100 patients without apical prolapse (with prolapse of the anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall).

Results: The analysis identified lifestyle features and clinical factors, which have statistically significant relationship with occurrence of apical prolapse: hard physical job, advanced age for a first birth, apical prolapse in first-degree relatives, prolonged labor for a first birth, weight gain during pregnancy and duration of postmenopause. Analysis determined threshold values of the indicators which increase the probability of occurrence of apical prolapse. Thus, the value of the weight gain of 13 kg during pregnancy was determined as a threshold value; the value exceeding this threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 4.15 times (odds ratio (OR)=4.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.38–7.21, p<0.001). Duration of postmenopause for more than 7 years was determined as a threshold value; the value exceeding the threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 2.79 times (OR=2.79, 95% CI 1.63–4.77, p<0.001). Duration of labor in first-time mothers for more than 15.5 hours was determined as the threshold value; the value exceeding the threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 3.48 times (OR=3.48, 95% CI 2.02–6.00, p<0.001). The age for the first birth over 22 years was determined as a threshold value, the value exceeding the threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 9.57 times (OR=9.57, 95% CI 5.23–17.51, p<0.001).

Conclusion: This study made it possible to identify for the first time a number of clinical factors and the features of lifestyle, pregnancy, labor and duration of postmenopause associated with apical prolapse. The calculated threshold values and odds ratios for these factors may help understand and manage risk occurrence of apical prolapse in parous women.

Authors' contributions: Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S. – development of the concept and design of the study; Matskevich E.N., Babicheva I.A. – material collection and processing; Matskevich E.N., Dubinskaya E.D. – article writing; Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S., Matskevich E.N., Babicheva I.A. – article editing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The study was carried out without any sponsorship.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S., Matskevich E.N., Babicheva I.A.

Clinical and anamnestic factors and lifestyle features significantly influencing apical prolapse.

Akusherstvo i Gynekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (3): 128-135 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.303

Keywords

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is one of the most relevant issues in gynecology. Every year there is growing attention to this topical problem. Millions of women worldwide experience POP; and the greatest burden of this condition is low-income countries [1]. Special attention is focused on patients with apical prolapse, which is the most pronounced and severe type of pelvic organ prolapse. The prevalence of apical prolapse is about 9% in the population in general, and reaches 56.4% in low-income countries [1].

It is especially difficult to correct the apical defects in this group of patients to improve their quality of live and prevent recurrence. On the one hand, apical prolapse is not a life-threatening condition, although in some cases it can even cause acute kidney damage [2]. On the other hand, the presence of the most common type of POP is an indication for different types of surgical treatment using mesh implants [3], but their unification and effectiveness is far from perfect.

It is known that apical prolapse is associated with impairment of level 1 of pelvic floor support, which includes the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. These ligaments differ significantly in structure from, for example, the knee ligaments and are considered as bilateral mesenteries of the female genital tract, consisting of blood vessels, lymphoid tissue, nerves embedded in adipose tissue in combination with connective tissue septa [4]. The stiffness of the uterosacral complex, comprised of the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, is 0.94 N/mm compared with the stiffness of anterior cruciate ligament of the knee – 200 N/mm) [5].

Analysis of literature data showed that individual significant factors for apical prolapse have been insufficiently studied [1]. It remains unclear today, why in some women prolapse is represented only by impairment of levels 2 and 3 of pelvic floor support (vaginal wall prolapse), and in other women by apical vaginal support loss.

The scientific hypothesis of the present study, requiring confirmation or refutation, was the assumption that patients with apical prolapse may have some clinical and anamnestic features that lead to impairment of level 1 of pelvic floor support.

The objective of this study was to evaluate lifestyle features and significant clinical and anamnestic factors associated with apical prolapse in parous women.

Materials and methods

A single-center retrospective case-control study using simple random selection included 270 women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) who underwent examination and treatment at the University Clinic “I am healthy” from 2017 to 2024.

Selection of cases and controls: The patients were randomly selected from the Clinic’s database. The selection was carried out among those women who met the inclusion criteria: the diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse, age over 18 years, availability of complete medical records. The patients with concomitant severe diseases, which could affect the results of the study, were excluded from the study.

Some participants dropped out of study in the initial step, and thus, the overall sample size was reduced to the current size (n=230). The following groups of women were excluded from the study: with hysterectomy in history n=7); surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in history (n=15); malignant neoplasms (n=2); incomplete medical records (n=10); nulliparous women (n=6).

Representativeness of the sample: All patients included in the study were representatives of typical population of women with pelvic organ prolapse, who underwent treatment at the University Clinic “I am healthy” during the mentioned period of time. A wide range of social-and demographic characteristics of this population made it possible to generalize the results of the study for women with pelvic organ prolapse, who undergo treatment in similar medical facilities.

The major inclusion criterion for the main group (n=130) was the presence of any stage of apical prolapse (POP-Q [6]) (incomplete and complete uterine prolapse [N 81.2; N 81.3]), and vaginal delivery. In the presence of any stage of apical prolapse, even in cases when point C was not the topmost point according to POP-Q, the patient was included in the main group.

Exclusion criteria for the main group were: hysterectomy, surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in history; the presence of malignant neoplasms; incomplete medical records; nulliparous patients. After checking compliance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 130 parous women with apical prolapse, who had vaginal delivery, were included in the main group (“case”),

The inclusion criterion for the control group was the presence of anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse without apical prolapse in women, who had vaginal delivery.

Exclusion criteria from the control group were the following: a combination of vaginal wall prolapse and apical prolapse; hysterectomy and surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in history; the presence of malignant neoplasms; incomplete medical records; nulliparous patients. After checking compliance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 100 women with anterior/ posterior vaginal wall prolapse, who had vaginal delivery and had no apical prolapse (POP-Q [6]) ([N 81.1; N 81.6]) were included in the control group.

Handling data losses: cases with incomplete medical records were excluded from analysis to minimize bias and ensure validity of the results.

All patients underwent medical examination to the uniform scheme, which included assessment of complaints, collection of anamnestic data, the general examination, and assessment of the gynecological status.

The study included analysis of lifestyle, socio-demographic, clinical and anamnestic characteristics, and lifestyle features of female patients in the groups under study. Analysis of clinical and anamnestic study included assessment of patient complaints; exploration of anamnesis: the features of the course of pregnancy and labor (weight gain during pregnancy, number of births, age for the first birth, duration of labor, complicated labor); the presence of gynecological and somatic diseases; lifestyle and external factors (smoking, weightlifting, sedentary lifestyle, occupational hazards); hereditary diseases and predisposition for pelvic organ prolapse.

The stage of pelvic organ prolapse was detected using POP-Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification) system. The POP-Q system was proposed by International Continence Society in 1996, and is based on objective quantification assessment in cm [6]. During gynecological examination, the main parameters were measured using the Valsalva maneuver with POP-Q measurement of Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp, C, D, gh, pb, and total vaginal length (TVL). In accordance with the clinical guidelines for connective tissue dysplasia (CTD), the phenotypic signs and manifestations of undifferentiated conneсtive tissue dysplasia (UCTD) were assessed [7]. The diagnosis of UCTD was made in the presence of findings in at least two body systems.

Statistical analysis

The obtained results were analyzed using statistical software programs SPSS (Version 10.0.7) and Statistica (Version 6.0) for Windows. Some data calculations were performed using formulas in Excel. The differences between the groups were considered as statistically significant at p<0.05.

For each group of patients, distribution of quantitative variable was tested for normality of distribution using the Kholmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables are represented as arithmetic mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). Distribution of variables different from normal is described as median (Me) and interquartile range (Q1; Q3). The qualitative variables are represented as absolute (n) and relative (%) values.

Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) test or Fisher's exact test for small samples was used to compare dichotomous variables between independent samples. Student t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare quantitative variable in the groups.

The significance level of 0.05 was set to test statistical hypothesis.

Different tools were used for evaluation of threshold values were used in the study to calculate odds ratios. The differences were considered to be statistically significant at p<0.05.

Binary logistic regression was used for stepwise forward variable selection. Inclusion of each subsequent factor was accompanied by cross-checking of the obtained scaling points, determination of sensitivity and specificity, collinearity of variables, as well as variance inflation factors (VIFs), and reliability indicators. Sensitivity and specificity criteria not less than 80% and the significance level of the included variables was at p<0.05.

To determine the threshold values of the studied indicators and to assess association between the studied factors and occurrence of apical prolapse, the following methods of analysis were used:

- Youden's Index is the value that maximizes the difference between sensitivity and specificity, that is Youden's Index = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1.

- Least Squares Estimation: This method estimates the parameters by minimizing the squared discrepancies between observed data and their expected values.

- P-Value Method is used to determine the threshold (p-value is the smallest level of significance) for testing the highest level of significance of the given confidence interval.

- Maximizing F1 score: This method maximizes the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall

- The Minimum Cost Method: This method takes into consideration the costs of classification errors (false positives and false negatives) and chooses a threshold minimizing the total cost of these errors.

For the cumulative total of values and the table, the arithmetic mean of the threshold values using different methods was calculated to obtain threshold balanced accuracy.

All methods used in the study are suitable for post-hoc analysis, as they help to analyze the data after completion of the experiment, do not require pre-hoc hypotheses, and allow explore the data to discover significant patterns and relationships.

Results

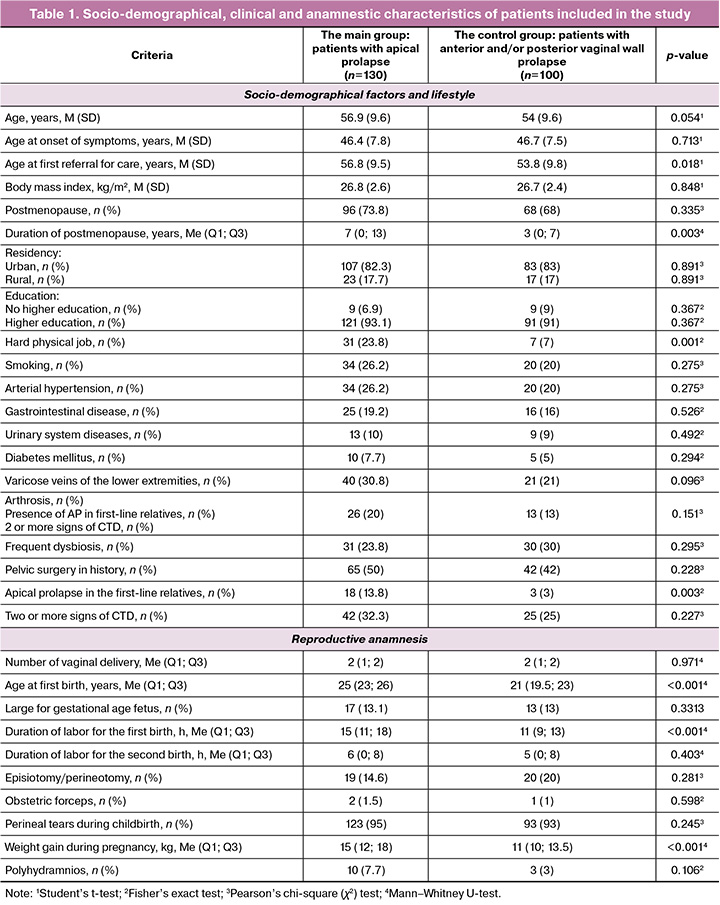

The results of assessment of socio-demographical, clinical and anamnestic characteristics and phenotypic traits of patients under study are represented in Table 1.

Thus, the socio-demographical, clinical and anamnestic characteristics in the groups were comparable in general.

To test possible protective effect of cigarette smoking on caesarean section reported in literature [8] (a meta-analysis suggesting such effects), separate logistic regression models were built for the smoking variables, including multi-stage models. Analysis showed that the suggested protective effect of smoking was not confirmed in general. On the contrary, a direct relationship was found between cigarette smoking and the risk for developing prolapses, and pelvic organ prolapse. Although, for transition from the category "healthy" (0) to the initial stage of prolapse (1), a negative coefficient was obtained, that indicates a decline in the probability of such transition with smoking. For all other severe degrees of prolapse (transitions from 1 to 2, from 2 to 3, from 3 to 4), a positive dependence on smoking was observed.

These results require cautious interpretation, since most available studies have explored smoking in the context of pelvic organ prolapse, whereas our study differentiates between the presence and absence of apical prolapse.

Moreover, remains limited, that should also be taken into account when interpreting the data. Despite these limitations, we represent our findings, which can serve as a basis for further research in this area.

As for cesarean section, it is not possible to assess the impact of CS on the development of prolapse, since during preparing and selection of patients it was found that women with cesarean section had virtually no prolapse. This confirms with both general clinical experience and our observation in the clinic. For this reason, such patients were not included in the study.

As follows from the data represented in the study, the patients with apical prolapse significantly more often had hard physical job, advanced age at first birth, the presence of apical prolapse in first-line relatives, prolonged labor for the first birth, and increased weight gain during pregnancy. No statistical significance was found for complicated births, large for gestational age fetuses, and number of births. There were also no significant differences found in frequency of cigarette smoking, social characteristics, and presence of CTD.

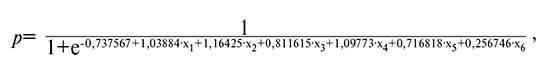

In the next step, as a result of using binary logistic regression analysis, the explicit form of the logistic function model was represented in this study:

where

x1 – duration of labor for the first birth;

x2 – age for the first birth;

x3 – family history (apical prolapse in first-degree relatives);

x4 – weight gain during pregnancy;

x5 – hard physical job;

x6 – duration of postmenopause.

Indicators of the model: AIC: 176.69119749541184, BIC: 200.75775265787422, Log-Likelihood: -81.34559874770592, Pseudo R-squared: 0.4834.

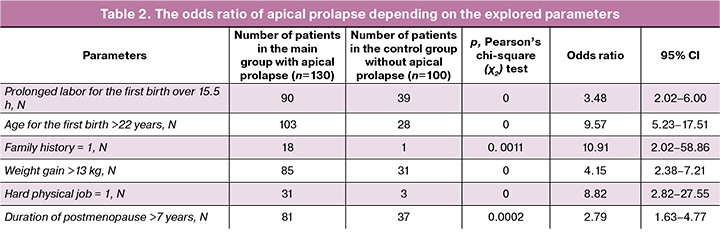

Table 2 represents analysis of the factors that are significant for apical prolapse in the group under study.

Thus, the value of the weight gain of 13 kg during pregnancy was determined as the threshold; the value greater than this threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 4.15 times (the odds ratio (OR)=4.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.38–7.21, p<0.001)). Duration of postmenopause for more than 7 years was determined as the threshold; the value exceeding the threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 2.79 times (OR=2.79, 95% CI 1.63–4.77, p<0.001). Prolonged labor for the first birth over15.5 hours was determined as the threshold; the value exceeding the threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 3.48 times (OR=3.48, 95% CI 2.02–6.00, p<0.001). The age for the first birth over 22 years was determined as the threshold, the value exceeding the threshold was associated with increased probability of occurrence of apical prolapse by 9.57 times (OR=9.57, 95% CI 5.23–17.51, p<0.001).

Discussion

The results of our study indicated that apical prolapse in parous women is associated with the following lifestyle features and clinical and anamnestic factors: weight gain of 13 kg during pregnancy; duration of postmenopause for more than 7 years; prolonged labor for the first birth over 15.5 hours; age for the first birth over 22 years; hard physical job; apical prolapse in first-degree relatives. It is interesting to note that there were no significant differences in birth traumas in general, and the presence of CTD between the group of women with apical prolapse and the patients who had only vaginal wall prolapse.

The majority of studies devoted to apical prolapse are represented by surgical correction technologies and assessment of recurrence rate [9–11]. At the same time, analysis of significant relationships mainly includes comparison between the patients with prolapse as a whole, without taking into account the individual characteristics of anatomic disorders (all types of pelvic organ prolapse) and healthy control [8]. The purpose of this study was to identify the factors that are directly associated with apical prolapse.

In most studies on prolapse, it is generally recognized that the main risk factors for prolapse are the following: vaginal delivery, fetal birth weight, age, body mass index, levator defect and enlarged vaginal opening, genetic predisposition, and lifestyle [12–14]. In our study, no statistically significant relationship was found between body mass index, parity, fetal birth weight, and the presence of apical prolapse. The data obtained by us in terms of parity in POP are similar to the results in the study by Fang J. et al. [15]. The data on the impact of excess body weight are also conflicting. A number of studies indicate that body mass index is a statistically significant risk factor for prolapse [8, 16]. Other authors report that woman’s body mass index has no impact on prolapse [17, 18]. Meta-analysis (2021) also confirmed that woman’s body mass index has no significant impact on development of pelvic organ prolapse [17], that conforms to the results of our study.

Given female pelvic floor biomechanics and the structure of level 1 of pelvic floor support, it is logical to suggest the presence of some features of pregnancy and vaginal delivery specifically associated with apical prolapse, taking into account the fact that apical prolapse is anatomically associated with impairment of uterosacral and cardinal ligaments that provide apical support to the uterus and upper vagina.

Unfortunately, there are few data in literature on risk factors for apical prolapse, with the exception of the study by Lologaeva M.S. et al., who explored predictors of severe types of pelvic organ prolapse. The results of their study indicate that the main factors associated with apical prolapse are age over 62 years, postmenopause (that indicates staging and progression of prolapse), duration of menopause over 10 years, traumatic injuries during childbirth and varicose disease [19].

Age as a factor associated with formation of apical prolapse was excluded from our study, and the age of patients was comparable. It should be noted that the youngest age of patient with apical prolapse, who was included in the study, was 35 years. In our opinion, a theory of inevitable prolapse progression from the stage of vaginal wall prolapse to formation of apical prolapse is highly controversial.

Most probably, it occurs due to evolution of existing disorders (possibly not diagnosed at an early stage), that is generally associated with aging of the extracellular matrix, changes in collagenase activity and collagen metabolism. Our suggestions correlate by the findings in the study by Handa V.L. et al., which showed that with age, prolapse is not necessarily a progressive disease, but can also spontaneously regress, especially in the case of stage 1 prolapse [20].

It is known that during pregnancy, the pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue become weakened due to the influence of hormonal changes, that leads to stretching to allow the passage of the fetus through the birth canal [21]. The pelvic floor muscle strength and function is recovered within a few months after childbirth. At the same time, it should not be forgotten that during pregnancy the uterine ligaments undergo changes, and acceleration of these changes is caused by denervation during delivery [22]. For example, it is known that uterosacral ligaments experience the growth in length at 16, 32, and 38 weeks of pregnancy. At the same time, 2 months after childbirth they return to the length at 16 weeks of pregnancy [23]. Uterosacral ligaments are strong supportive structures and before impairment of their functional state are able to support about 17 kg of weight in the attachment point at cervix, and up to 5 kg at sacrum [24].

Currently, finite element analysis gives us insights into biomechanics of the uterine ligaments. It is known that the uterus is affected by intra-abdominal pressure and gravity; the direction of pelvic floor gravity is vertical, intra-abdominal pressure affects the uterus. According to the integral theory, the normal position of the uterus depends on the balance between the support force (ligaments) and the load. In addition, some researchers have found that changes in body position has direct influence on intra-abdominal pressure [25]. Thus, the position of the body influence the stress response and the position of the uterine ligaments and, as a consequence, the position of the uterus [25].

In fact, our study confirmed the presence of pregnancy-associated factors that significantly and to a critical level increase intra-abdominal pressure, that along with genetic predispositions in combination with lifestyle features and age, leads to impairment of the functional state of ligaments of the uterus and, as a consequence, to occurrence of apical prolapse.

The limitations of our study is an average cohort size. It is also possible that there could be “memory errors” in collecting anamnesis related to the features of pregnancy and childbirth.

Conclusion

This study made it possible to identify a number of lifestyle features and clinical and anamnestic factors significant for apical prolapse. It is possible that these factors in one way or another influence the state of the uterosacral complex that provides level 1 of pelvic floor support. It is important that the identified significant factors have impact on intra-abdominal pressure (hard physical job, weight gain during pregnancy) and characteristics of ligaments of the uterus (the age for the first birth, duration of postmenopause). Hereditary background is also an undoubted factor, and its importance is undeniable in the etiology of pelvic organ prolapse in general.

References

- Badacho A.S., Lelu M.A., Gelan Z., Woltamo D.D. Uterine prolapse and associated factors among reproductive-age women in south-west Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022; 17(1): e0262077. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262077.

- Khaleel M., Ayyad M., Albandak M., C. N. Khalil N., M. A. Abu Taleb S. Acute renal failure caused by undiagnosed pelvic organ prolapse in a postmenopausal woman: a diagnosis not to be missed. Cureus. 2023; 15(9): e44513. https://dx.doi.org/10.7759/cureus.44513.

- Geoffrion R., Larouche M. Guideline No. 413: Surgical management of apical pelvic organ prolapse in women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2021; 43(4): 511-523.e1. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2021.02.001.

- Kieserman-Shmokler C., Swenson C.W., Chen L., Desmond L.M., Ashton-Miller J.A., DeLancey J.O. From molecular to macro: the key role of the apical ligaments in uterovaginal support. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 222(5): 427-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.006.

- Woo S.L., Hollis J.M., Adams D.J., Lyon R.M., Takai S. Tensile properties of the human femur-anterior cruciate ligament-tibia complex. The effects of specimen age and orientation. Am. J. Sports Med. 1991; 19(3): 217-25. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/036354659101900303.

- Madhu C., Swift S., Moloney-Geany S., Drake M.J. How to use the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system? Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018; 37(S6): S39-S43. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nau.23740.

- Российское научное медицинское общество терапевтов (РНМОТ). Клинические рекомендации. Дисплазии соединительной ткани. 2017. [Russian Scientific Medical Society of Therapists. Clinical guidelines. Connective tissue dysplasias. 2017. (in Russian)].

- Schulten S.F.M., Claas-Quax M.J., Weemhoff M., van Eijndhoven H.W., van Leijsen S.A., Vergeldt T.F. et al. Risk factors for primary pelvic organ prolapse and prolapse recurrence: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022; 227(2): 192-208. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.046.

- Lu Z., Chen Y., Xiao C., Hua K., Hu C. Transvaginal extraperitoneal single-port laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for apical prolapse after total/subtotal hysterectomy: Chinese surgeons' initial experience. BMC Surg. 2024; 24(1): 25. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-02304-z.

- Meyer I., Blanchard C.T., Szychowski J.M., Richter H.E. Five-year surgical outcomes of transvaginal apical approaches in women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023; 34(9): 2171-81. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05501-9.

- Chan C.Y.W., Fernandes R.A., Yao H.H., O'Connell H.E., Tse V., Gani J. A systematic review of the surgical management of apical pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023; 34(4): 825-41. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05408-x.

- Samimi P., Jones S.H., Giri A. Family history and pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021; 32(4): 759-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04559-z.

- Kato J., Nagata C., Miwa K., Ito N., Morishige K.I. Pelvic organ prolapse and Japanese lifestyle: prevalence and risk factors in Japan. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022; 33(1): 47-51. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04672-7.

- Brito L.G.O., Pereira G.M.V., Moalli P., Shynlova O., Manonai J., Weintraub A.Y. et al. Age and/or postmenopausal status as risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse development: systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022; 33(1): 15-29. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04953-1.

- Fang J., Zhang R., Lin S., Lai B., Chen Y., Lu Y. et al. Impact of parity on pelvic floor morphology and function: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023; 102(45): e35738. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000035738.

- Fitz F.F., Bortolini M.A.T., Pereira G.M.V., Salerno G.R.F., Castro R.A. PEOPLE: Lifestyle and comorbidities as risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse-a systematic review and meta-analysis PEOPLE: PElvic Organ Prolapse Lifestyle comorbiditiEs. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023; 34(9): 2007-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05569-3.

- Zenebe C.B., Chanie W.F., Aregawi A.B., Andargie T.M., Mihret M.S. The effect of women's body mass index on pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta analysis. Reprod. Health. 2021; 18(1): 45. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01104-z.

- Pudasaini S., Dangal G. Clinical profile of patients of pelvic organ prolapse and its associated factors. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2023; 21(1): 86-91. https://dx.doi.org/10.33314/jnhrc.v21i1.4361.

- Лологаева М.С., Арютин Д.Г., Оразов М.Р., Токтар Л.Р., Ваганов Е.Ф., Каримова Г.А. Пролапс тазовых органов в XXI в. Акушерство и гинекология: новости, мнения, обучение. 2019; 7(3): 76-82. [Lologaeva M.S., Aryutin D.G., Orazov M.R.,Toktar L.R., Vaganov E.F., Karimova G.A. Pelvic organ prolapse in XXI century. Obstetrics and Gynecology: News, Opinions, Training. 2019; 7(3): 76-82. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2303-9698-2019-13011.

- Handa V.L., Garrett E., Hendrix S., Gold E., Robbins J. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004; 190(1): 27-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2003.07.017.

- Socha M.W., Flis W., Pietrus M., Wartęga M., Stankiewicz M. Signaling pathways regulating human cervical ripening in preterm and term delivery. Cells. 2022; 11(22): 3690. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/cells11223690.

- Bhattarai A., Staat M. Modelling of soft connective tissues to investigate female pelvic floor dysfunctions. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2018; 2018: 9518076. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/9518076.

- Jean Dit Gautier E., Mayeur O., Lepage J., Brieu M., Cosson M., Rubod C. Pregnancy impact on uterosacral ligament and pelvic muscles using a 3D numerical and finite element model: preliminary results. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018; 29(3): 425-30. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3520-3.

- Buller J.L., Thompson J.R., Cundiff G.W., Krueger Sullivan L., Schön Ybarra M.A., Bent A.E. Uterosacral ligament: description of anatomic relationships to optimize surgical safety. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001; 97(6): 873-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01346-1.

- Chen J., Zhang J., Wang F. A finite element analysis of different postures and intra-abdominal pressures for the uterine ligaments in maintaining the normal position of uterus. Sci. Rep. 2023; 13(1): 5082. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32368-z.

Received 02.12.2024

Accepted 14.02.2025

About the Authors

Ekaterina D. Dubinskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology with Course of Perinatology, Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, 8 Miklukho-Maklaya str., Moscow, 117198, Russia, +7(903)117-55-58, eka-dubinskaya@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8311-0381Alexander S. Gasparov, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology with Course of Perinatology, Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University

of Russia, 8 Miklukho-Maklaya str., Moscow, 117198, Russia, +7(903) 117-55-58, 13513520@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6301-1880

Elizaveta N. Matskevich, Teaching Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine, Faculty of Continuing Medical Education,

Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, 5-2 General Antonov str., Moscow, 117342, Russia, +7(911)176-66-94, liza151196chik@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3315-7408

Irina A. Babicheva, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine, Faculty of Continuing Medical Education,

Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, 8 Miklukho-Maklaya str., Moscow, 117198, Russia, +7(916)500-10-99, babicheva200751@mail.ru

Corresponding author: Ekaterina D. Dubinskaya, eka-dubinskaya@yandex.ru