Clinical use of expanded genetic testing in the management of couples with unexplained infertility

Martirosyan Ya.O., Kadaeva A.I., Bolshakova A.S., Nazarenko T.A., Biryukova A.M., Askeralieva A.N.

Objective: To clarify the proportion of unexplained infertility within the overall structure of infertility and analyze the clinical, embryologic, and genetic characteristics of patients with unexplained infertility (UI).

Materials and methods: Patients were selected from couples referred for IVF/ICSI programs. In the retrospective phase of the study, clinical and medical history data were analyzed from 1,500 married couples who underwent 2,156 stimulated cycles from 2020 to 2022 at V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P. The observation group consisted of 156 married couples diagnosed with unexplained infertility, who were referred for IVF.

Results: Of the total number of patients included in the study, 10.4% were diagnosed with unexplained infertility. The cause of infertility was established in 89.6% of the couples. Patients with UI had a longer duration of infertility (on average 4.3 (1.2) years) compared to patients with an established cause of infertility (3.2 (2.4) years), with a statistically significant difference (p<0.001, Student's t-test). Patients with UI also exhibited lower AMH levels and lower antral follicle counts compared to the control group: mean levels were 2.6 (0.46) and 13.3 (2.9), respectively, versus 3.61 (2.04) and 14.2 (4.0) (p<0.001 and p=0.004, Mann–Whitney U-test). The number of oocytes retrieved by transvaginal ovarian puncture was similar in both the groups. Comparison of the parameters of subsequent embryological stages showed that all patients with UI had significantly reduced parameters compared to those in the group with an established cause of infertility: mature oocytes were 33.3% lower, correctly fertilized oocytes were 45.5% lower, and the number of embryos (blastocysts) available for transfer was 82.2% lower. Patients with UI who did not have blastocysts retrieved on day 5 of culture underwent genetic testing, which revealed genetic variants potentially linked to IVF failure.

Conclusion: Identifying the specific genetic determinants of female infertility enables a definitive diagnosis for couples, allowing them to consider alternative ART options. It also provides an opportunity to identify molecular factors and biological pathways involved in the acquisition of oocyte competence.

Authors' contributions: Martirosyan Ya.O., Kadayeva A.I., Bolshakova A.S., Nazarenko T.A., Biryukova A.M., Askeralieva A.N. – conception and design of the study, obtaining data for analysis, review of relevant publications, obtained data analysis, drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: Source of funding: R&D 121040600410-7 Nazarenko T.A. “Solving the problem of infertility in modern conditions by developing a clinical and diagnostic model of infertile marriage and using innovative technologies in assisted reproduction programs.”

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Martirosyan Ya.O., Kadaeva A.I., Bolshakova A.S., Nazarenko T.A., Biryukova A.M., Askeralieva A.N. Clinical use of expanded genetic testing in the management of couples with unexplained infertility.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024; (12): 50-58 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.274

Keywords

Female infertility is a complex disorder characterized by significant heterogeneity owing to the intricate interplay of multiple factors. Genetic, immunological, endocrine, and anatomical abnormalities can influence a woman’s chances of becoming pregnant. Although infertility as an isolated symptom is not uncommon in women, very little is known about the genetic basis of isolated female infertility, especially when compared to male infertility. Due to this lack of understanding regarding genetic influences on female fertility, few genetic tests are routinely recommended to investigate the underlying causes of infertility. Consequently, a significant proportion of couples seeking assisted reproductive technology (ART) are diagnosed with idiopathic infertility, for which no obvious cause of reproductive failure can be identified. In some cases, the use of in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) enables the identification of defects in oocyte and embryo maturation and development that can only be observed ex vivo. These defects may include complete arrest of oocyte maturation, complete failure of fertilization, and complete preimplantation embryonic lethality [1–3].

The recurrence of these defects in oogenesis and embryogenesis, particularly when observed over multiple treatment cycles, suggests a possible genetic cause. Advanced testing methods, including high-throughput sequencing, have facilitated the discovery of new genomic variants that can significantly affect oogenesis and embryonic development. Identifying a specific genetic determinant of female infertility not only provides a definitive diagnosis for couples, allowing them to consider alternative ART options, but also offers an opportunity to elucidate the molecular players and biological pathways involved in achieving oocyte competence. Below, we explore examples of how this approach has helped identify pathological mechanisms that affect oocyte competence and lead to individual infertility phenotypes.

This study aimed to clarify the proportion of unexplained infertility within the overall spectrum of infertility and to analyze the clinical, embryologic, and genetic characteristics of patients with unexplained infertility (UI).

Materials and methods

Patients for this study were selected from couples referred for IVF/ICSI treatment at the F. Paulsen Research and Clinical Department of ART (Head of Department: Nazarenko, Dr. Med. Sci.) based on inclusion and exclusion criteria aligned with the study objectives.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: infertility, indications for the IVF program, a history of IVF/ICSI failure, and no contraindications to ART.

Exclusion criteria included the use of donor gametes in the studied ART cycle, acute infectious diseases, spouse, absolute asthenozoospermia, cryptozoospermia (single spermatozoa in the ejaculate), or sperm retrieval by surgery.

All couples participating in the study underwent thorough clinical and laboratory examinations in accordance with the current regulatory documents of the Russian Federation. All patients signed an informed consent form approved by the Ethics Committee.

In the retrospective stage of the study, clinical and anamnestic data from 1,500 married couples were analyzed, who underwent 2,156 stimulated cycles between 2020 and 2022 at the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P. An initial analysis was conducted to identify the causes of infertility in the couples included in the study. Two main groups were identified: group 1 included patients with an established cause of infertility, while group 2 included patients with unexplained infertility (UI). Of the 156 married couples who were referred for IVF treatment, UI was diagnosed, which is a nomenclature form of infertility classified under ICD-10 as "N97.8 Other forms of female infertility," as it is not recognized as a distinct form of infertility (XXXII Annual International Conference of the Russian Association of Reproductive Technologies "Reproductive Technologies Today and Tomorrow," 2022).

The control group consisted of patients with secondary infertility due to factors such as occlusion of the fallopian tubes following operations for small pelvis hydrosalpinx and sactosalpinx, adhesions, etc., who had children without genetic disorders.

Additionally, 50 patients aged <38 years with primary UI were selected from the observation group. These patients had a history of repeated IVF failure, characterized by the absence of embryos suitable for transfer into the uterine cavity. These couples underwent extensive genetic examination, which included karyotype analysis at the first stage and high-throughput sequencing at the second stage. Patients with reduced ovarian reserve were also advised to determine the number of trinucleotide CGG repeats in FMR1.

A sample of the spouses' peripheral blood was collected into heparin-containing tubes. Karyotype analysis was performed using the standard cultivation technique with differential G-staining of chromosomes. For high-throughput sequencing, genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using the PROBA-MCh MAX DNA extraction kit (DNA Technology, Russia). Patient DNA was sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform (whole exome sequencing - WES). The IDT XGen Exome Hyb Panel v2 enrichment kit was used to enrich target fragments. During the processing of sequencing data, an algorithm was employed that included aligning reads to the hg38 reference genome sequence, calling, and filtering variants by quality. All variants that passed quality filtering were annotated using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) and several variant significance prediction algorithms (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and SpliceAI). The clinical significance (pathogenicity) of the identified variants was assessed based on the recommendations of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [4] and Russian guidelines for data interpretation [5] obtained through high-throughput sequencing methods [6, 7]. The number of trinucleotide CGG repeats in FMR1 was determined by amplifying the promoter region of the gene using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with fluorescently labeled primers and quantifying the length of PCR products through fragment analysis. The conversion of amplicon lengths to the number of repeats was performed using external standards for fragment lengths and internal control samples [8–10]. Repeats of 28–36 were considered normal. A repeat count of less than 28 defined a short allele, more than 36 and less than 55 defined an intermediate allele, more than 55 and less than 200 defined a premutation, and more than 200 defined a full mutation [11, 12].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and comparative statistics were used to analyze the data.

Continuous variables that followed a normal distribution are expressed as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) and presented as M (SD). Otherwise, the median and interquartile range are reported. Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to assess differences between groups. The assumptions of the parametric methods (Student's t-test and ANOVA) were validated by confirming normal distribution and equality of variances within the compared groups. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, USA) (P6). The critical level of significance for interpreting results was set at p<0.05, Student's t-test.

Results

Of the total number of patients included in the study, 10.4% were diagnosed with unexplained infertility (UI). Reasons for the absence of pregnancy were established in 89.6% of couples.

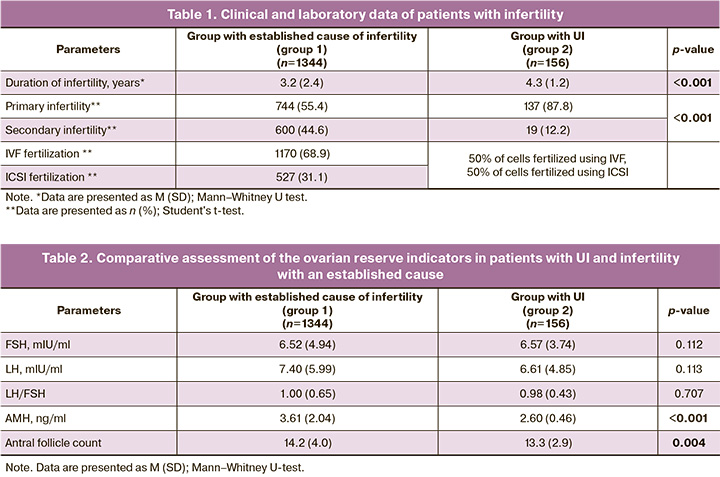

The main clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients included in the study are presented in Table 1. The average duration of infertility for patients in group 1 was 3.2 years, while in group 2, it was on average 4.3 years. The vast majority of patients in group 2 had primary infertility, with 19/156 (12.2%) having secondary infertility and recurrent miscarriage (Table 1). Thus, patients with UI were characterized by a longer duration of infertility.

Analysis of quantitative parameters of ovarian reserve showed that the antral follicle count and the levels of hormones associated with ovarian reserve, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)in patients with UI were within the normal range. However, patients with UI exhibited lower AMH values and lower antral follicle counts than patients with an established cause of infertility (AMH: p<0.001, Mann–Whitney U-test; antral follicle counts: p=0.004, Mann–Whitney U-test).

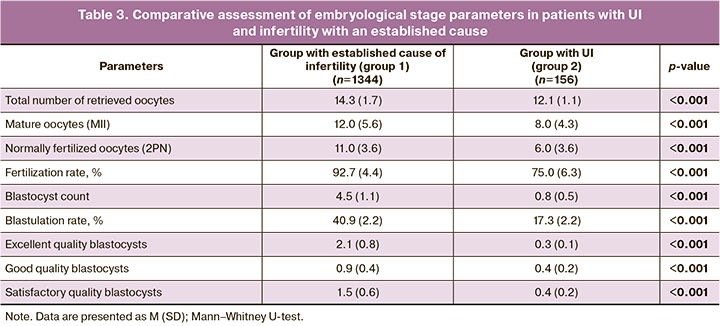

In group 1, an average of 14 oocytes were obtained after transvaginal ovarian puncture. The average IVF and ICSI fertilization rates were 92.7% and 91.0% for ICSI. After 5 days of culture, an average of 4–5 blastocysts (Table 3) suitable for transfer into the uterine cavity were obtained, representing 550/1344 (40.9%) of correctly fertilized eggs and approximately 37.5% of mature oocytes. The proportion of oocytes that developed to the blastocyst stage, suitable for transfer into the uterus from the total number of oocytes retrieved by transvaginal ovarian puncture, was even lower, averaging 31.5%.

In group 2, an average of 12 oocytes were obtained, of which only 66.1% were mature. These mature oocytes were fertilized: 50% by IVF and 50% by ICSI. The average fertilization rate was 75% in both groups, with no statistically significant differences between the groups. Thus, it can be concluded that fertilization by ICSI does not increase the likelihood of a favorable outcome in couples with UI.

On the 5th day of culture (Table 3), single blastocysts suitable for transfer into the uterine cavity were obtained from only a small number of patients (n=26). On average, only 17% of the correctly fertilized oocytes had developmental potential and were able to progress to the blastocyst stage, which is suitable for transfer.

During early embryonic development, starting from oocyte retrieval after transvaginal puncture and continuing to the development of viable embryos with high implantation potential, there is a significant reduction in the number of cells (embryos) capable of further development and successful implantation.

The number of oocytes retrieved after transvaginal puncture was nearly the same in both the patient groups (Table 3). A Comparison of the parameters of subsequent stages of the embryological stage indicates that in group 2 they are all significantly reduced compared to those in group 1 (Table 3): mature oocytes were 33.3% fewer, correctly fertilized ones were 45.5% fewer, and embryos (blastocysts) for transfer were 82.2% fewer.

Patients in group 2, who did not have blastocysts retrieved on day 5 of culture, underwent genetic testing. In the first stage, karyotyping of couples was performed.

Variants of normal chromosome polymorphisms were detected in three couples. In one case, a satellite region on the long arm of the Y chromosome (46,XYqs+) was found in the karyotype of the spouse; in another case, an increase in the length of the heterochromatic region of the long arm of the Y chromosome (46,XY,qh+) was noted. In the third case, the spouse had enlarged satellites on chromosomes 13 and 14 (46,XX,13ps+,14ps+).

Subsequently, the remaining patients underwent whole-exome sequencing of DNA from peripheral blood samples. Variants potentially linked to IVF failure were identified in seven of them.

Changes were recorded in the genes KPNA7, ZP1, TLE6, and TUBB8, which belong to the groups of "oocyte maturation defects" (OOMD) and "preimplantation embryo lethality" (PREMBL), and in the PALB2, BRCA1, and BRCA2 genes, which are responsible for DNA repair.

Additionally, one patient was found to be a carrier of a pathogenic variant of the DHCR7 gene, associated with Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome. This disease is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, with typical symptoms, including growth retardation, microcephaly, and cardiac and renal abnormalities. The literature [13] reports reduced fertility in carriers and/or early perinatal losses in couples where both parents were heterozygous carriers.

In the second couple, due to the birth of a child with Niemann–Pick disease type A/B, which follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, the parents were found to be carriers of pathogenic variants in the SMPD1 gene. This results in a high risk of disease recurrence in offspring. However, in this couple, failures in assisted reproductive technology (ART) were most likely associated with the advanced reproductive age of the patient.

Patients who experienced infertility, combined with a significant decrease in ovarian reserve were tested for the number of CGG repeats in the FMR1 gene. An intermediate allele was detected in one patient, with 43 repeats.

Here, we present two of the most striking clinical observations.

Clinical observation 1

Patient A was a 36-year-old woman. Diagnosis: Unexplained infertility I. She had a history of three IVF/ICSI programs using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol. In May 2018, 15 oocytes were obtained, and one embryo (2CC) was transferred on day 5, but this was unsuccessful; embryo cryopreservation was not performed. In March 2020, 15 oocytes and 12 zygotes were obtained; however, all the embryos ceased to develop. In November 2023, 11 oocytes were retrieved, and one embryo (morula C) was transferred on day 3, with no effect; again, embryo cryopreservation was not performed. Based on whole-exome sequencing results, the patient was found to have a previously undescribed heterozygous variant in the TLE6 gene, where homozygous variants were associated with impaired oocyte/zygote/embryo maturation arrest (15; OMIM: 616814). The variant was registered in the gnomAD control sample, with 56 mutant alleles identified among 1,613,992 chromosomes (no homozygotes were registered). Pathogenicity prediction algorithms classify the variant as either non-pathogenic (PolyPhen: 0.238) or pathogenic (Sift: 0.34). To clarify the clinical significance and search for a second variant in TLE6, the patient is scheduled for whole genome sequencing, which will also identify single nucleotide variants in non-coding (intronic) regions and small copy number variations.

Clinical observation 2

Patient V was a 30-year-old woman. Diagnosis: Unexplained infertility I. She had a history of undergoing two IVF/ICSI programs using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol. In November 2022, seven oocytes were retrieved and two embryos (morula B and morula C) were transferred on day 4; embryo cryopreservation was not performed. In May 2023, 17 oocytes were retrieved, and one embryo (four blastomeres) was transferred into the uterine cavity on day 2; embryo cryopreservation was not performed.

Based on the results of whole-exome sequencing, a previously undescribed heterozygous variant of KPNA7 was detected in the patient. Homozygous and compound heterozygous variants of KPNA7 have been described in patients with oocyte, zygote, and embryo maturation disorders. This variant was not detected in the gnomAD control samples. Pathogenicity prediction algorithms classified the variant as pathogenic (CADD: 32.0, PolyPhen: 0.942, Sift: 0.01). Given the failure to detect a second variant in KPNA7, the patient was offered whole-genome sequencing; however, she preferred to participate in the donor program.

Discussion

Oocyte aneuploidies are critical factors that are associated with oocyte competence. They can be inherited because of an abnormal maternal karyotype or, more commonly, arise de novo as a result of meiotic errors in chromosome segregation. Clinically, the most significant chromosomal structural abnormalities include Robertsonian and reciprocal translocation. Patients with translocations face a high risk of infertility and spontaneous abortions. This type of balanced rearrangement is relatively rare (with a prevalence of 1–2% in the infertile population) and is usually harmless to the carrier, as it does not involve the loss or gain of genetic material. However, this can lead to chromosomal linkage complications during meiosis. The error-prone chromosome segregation process, characteristic of female meiosis, is the most common cause of oocyte aneuploidy. The frequency of oocyte aneuploidy in humans is notably high, ranging from 25% to 85%, and increases rapidly after the age of 35 [14, 15].

However, some studies have reported a wide range of aneuploidy frequencies in both oocytes and embryos, even among women of the same age [16, 17]. Thus, age alone does not fully account for inter-individual variability in aneuploidy frequency. During gametogenesis, dividing germ cells undergo several fundamental and highly organized processes, including unification of homologous chromosomes into pairs, alignment, synapsis, and crossing over [17].

An important risk factor is the presence of pathogenic variants in the genes responsible for the assembly of the mitotic spindle, which can increase the frequency of aneuploidies even in younger women. Several authors have demonstrated that pathogenic variants in genes required for synapse formation during chromosomal recombination and segregation, such as STAG3, REC8, and SMC1B, are associated with embryonic chromosomal abnormalities and infertility [18, 19].

The use of high-throughput sequencing in infertile women displaying specific infertility phenotypes during IVF cycles (e.g., defective fertilization and embryo development arrest) has facilitated the discovery of novel genomic variants that may affect the reproductive competence of oocytes and embryos.

From birth onwards, oocyte maturation is arrested at the diplotene stage of prophase I of meiotic division. With the onset of puberty and menarche, this maturation process is selectively resumed in a limited cohort of follicles each month, which competitively grow under the influence of hormonal stimuli such as FSH, estrogens, and LH. A sharp increase in LH levels causes rupture of the dominant follicle and resumption of meiosis I in the ovulated egg, followed by chromatin condensation and dissolution of the oocyte nuclear membrane (i.e., the germinal vesicle). Severe disturbances in these processes can prevent gamete maturation, leading to oocyte inferiority and infertility.

For example, pathogenic homo- or compound heterozygous variants in PATL2 have been identified in women with primary infertility characterized by oocyte immaturity. PATL2 is an RNA-binding protein with regulatory functions in gene expression and is highly expressed in the germinal vesicle of human oocytes (MI oocytes). Pathogenic variants in PATL2 were first described in 2017 after their identification in consanguineous families with the germinal vesicle arrest phenotype [20, 21].

It is noteworthy that different patterns of embryological failure in IVF programs have been observed, depending on the specific genes involved. For example, there is arrest at the MI stage in the presence of pathogenic variants of the TUBB8 gene [22].

In humans, the zona pellucida consists of four glycoproteins known as ZP1-ZP4 [23]. Homozygous pathogenic variants in ZP1 were found in women with failed IVF/ICSI cycles, whose oocytes lacked the zona pellucida [24, 25]. Heterozygous pathogenic variants of the ZP3 gene, both hereditary and spontaneous, have been associated with empty follicle syndrome [26]. Despite ovarian stimulation, oocytes are not restored because the absence of the zona pellucida during oogenesis leads to premature oocyte degeneration [27]. Homozygous pathogenic variants in the ZP2 gene were identified in two consanguineous families, where oocytes exhibited an extremely thin zona pellucida, preventing sperm binding and resulting in fertilization failure [28].

Pathogenic variants in the TLE6 (Transducin-like enhancer of split-6) gene have been shown to prevent the fertilization of morphologically normal oocytes and their transition to the zygote stage [29]. In 2018, data on homozygous pathogenic variants of the WEE2 gene from four families with fertilization failure were published [30]. The BTG4 gene is the only well-studied gene associated with zygote cleavage failure to date [31].

Preimplantation embryonic lethality (PREMBL)

The in vitro culture of human embryos during IVF procedures has enabled the identification of infertility phenotypes that demonstrate early embryonic lethality. It is estimated that nearly 70% of human embryos obtained through IVF are viable, whereas approximately 30% do not thrive during the earliest stages of embryogenesis [32, 33].

After fertilization, mitosis is initiated and maintained by maternally inherited proteins and RNAs, which are gradually degraded during the initial rounds of cell division, while the embryonic genome remains transcriptionally inactive [34]. In humans, several genes involved in embryo-oocyte transition have recently been identified in well-characterized cases of infertility caused by early embryonic arrest. The subcortical maternal complex (SCMC) plays a key role in this transition and consists of at least eight proteins: OOEP, PADI6, TLE6, KHDC3L, NLRP4f, NLRP2, NLRP5, and ZBED3 [35–40].

Human reproductive function is regulated by numerous genes essential for a variety of cellular and physiological functions, ranging from maturation and differentiation of highly specialized cells to cell cycle control and hormonal signaling. Animal model studies have identified thousands of candidate genes and miRNAs that may be involved in various infertility phenotypes. These studies have shown that not only chromosomal abnormalities but also single-gene defects with Mendelian inheritance can lead to specific variants of infertility. However, differences remain between animal and human models. To date, high-throughput sequencing studies have made significant progress in identifying the causal genes for both syndromic and non-syndromic forms of female infertility. These defects can affect oocyte availability (e.g., by increasing the incidence of follicle exhaustion, leading to premature ovarian insufficiency) or dramatically reduce or even eliminate reproductive competition between oocytes and embryos (e.g., by systematically arresting maturation and development). Specific phenotypes of gamete incompetence and embryo lethality, such as oocyte atresia, oocyte maturation arrest, fertilization failure, and embryonic development arrest, can only be identified through in vitro fertilization (IVF). The use of high-throughput sequencing in patients suffering from these pathological phenotypes has facilitated the identification of new genes that are important for reproductive processes. Moreover, some of the genes involved in the symptomatology of female infertility exhibit pleiotropy, impacting multiple processes and pathways, and exerting different effects on the overall phenotype of the carrier. A typical example is FMR1, in which patients with a premutation and ovarian insufficiency experience an expansion of CGG trinucleotide repeats in their offspring, leading to more severe clinical manifestations, including intellectual disability in male offspring.

In addition, pathogenic variants in the BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 genes are known to increase the risk of cancer, primarily breast and ovarian cancer in women. However, women carrying pathogenic variants of these genes also have an increased risk of premature ovarian insufficiency [41].

Conclusion

The totality of the data shows that infertility is often not just the result of failing to conceive after 12 months of trying, but rather, it is a symptom of an underlying disease. Moreover, these diseases may not manifest in affected individuals but could potentially affect their children. Extended genetic testing may help to establish the cause of infertility and can therefore be considered a multifunctional approach with significant clinical benefits.

Its main purpose in reproductive medicine is to identify the genetic causes of infertility and prevent the transmission of pathogenic variants to offspring.

References

- Киракосян Е.В., Назаренко Т.А., Бачурин А.В., Павлович С.В. Клиническая характеристика и эмбриологические показатели программ экстракорпорального оплодотворения у женщин с бесплодием неясного генеза. Акушерство и гинекология. 2022; 5: 83-90. [Kirakosyan E.V., Nazarenko T.A., Bachurin A.V., Pavlovich S.V. Clinical characteristics and embryological parameters in IVF programs for women with unexplained infertility. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; (5): 83-90 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.5.83-90.

- Бачурин А.В., Киракосян Е.В., Назаренко Т.А., Павлович С.В. Анализ эмбриологического этапа программ экстракорпорального оплодотворения у пациентов с бесплодием неясного генеза. Акушерство и гинекология. 2022; 9: 81-6. [Bachurin A.V., Kirakosyan E.V., Nazarenko N.A., Pavlovich S.V. Analysis of the embryonic stage of in vitro fertilization programs in patients with unexplained infertility. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; (9): 81-6 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.9.81-86.

- Мартиросян Я.О., Назаренко Т.А., Кадаева А.И., Краснова В.Г., Бирюкова А.М., Погосян М.Т. Новые подходы к изучению регуляции преимплантационного развития эмбрионов. Акушерство и гинекология. 2023; 6: 29-37. [Martirosyan Ya.O., Nazarenko T.A., Kadaeva A.I., Krasnova V.G., Biryukova A.M., Pogosyan M.T. New approaches to studying the regulation of preimplantation embryonic development. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (6): 29-37 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.10.

- Green R.C., Berg J.S., Grody W.W., Kalia S.S., Korf B.R., Martin C.L. et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet. Med. 2013; 15(7): 565-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.73.

- Рыжкова О.П., Кардымон О.Л., Прохорчук Е.Б., Коновалов Ф.А., Масленников А.Б., Степанов В.А., Афанасьев А.А., Заклязьминская Е.В., Ребриков Д.В., Савостьянов К.В., Глотов А.С., Костарева А.А., Павлов А.Е., Голубенко М.В., Поляков А.В., Куцев С.И. Руководство по интерпретации данных последовательности ДНК человека, полученных методами массового параллельного секвенирования (MPS) (редакция 2018, версия 2). Медицинская генетика. 2019; 18(2): 3-23. [Ryzhkova O.P., Kardymon O.L., Prohorchuk E.B., Konovalov F.A., Maslennikov A.B., Stepanov V.A., Afanasyev A.A., Zaklyazminskaya E.V., Rebrikov D.V., Savostianov K.V., Glotov A.S., Kostareva A.A., Pavlov A.E., Golubenko M.V., Polyakov A.V., Kutsev S.I. Guidelines for the interpretation of massive parallel sequencing variants (update 2018, v2). Medical Genetics. 2019; 18(2): 3-23. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.25557/2073-7998.2019.02.3-23.

- Nykamp K., Anderson M., Powers M., Garcia J., Herrera B., Ho Y.Y. et al. Sherloc: a comprehensive refinement of the ACMG-AMP variant classification criteria. Genet. Med. 2017; 19(10): 1105-17. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.37.

- McGurk K.A., Zheng S.L., Henry A., Josephs K., Edwards M., de Marvao A. et al. Correspondence on “ACMG SF v3.0 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)” by Miller et al. Genet. Med. 2022; 24(3): 744-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2021.10.020.

- Chen L., Hadd A., Sah S., Filipovic-Sadic S., Krosting J., Sekinger E. et al. An information-rich CGG repeat primed PCR that detects the full range of fragile X expanded alleles and minimizes the need for southern blot analysis. J. Mol. Diagn. 2010; 12(5): 589-600. https://dx.doi.org/10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090227.

- Amos Wilson J., Pratt V.M., Phansalkar A., Muralidharan K., Highsmith W.E. Jr., Beck J.C. et al.; Fragile Xperts Working Group of the Association for Molecular Pathology Clinical Practice Committee. Consensus characterization of 16 FMR1 reference materials: a consortium study. J. Mol. Diagn. 2008; 10(1): 2-12. https://dx.doi.org/10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070105.

- Saluto A., Brussino A., Tassone F., Arduino C., Cagnoli C., Pappi P. et al. An enhanced polymerase chain reaction assay to detect pre- and full mutation alleles of the fragile X mental retardation 1 gene. J. Mol. Diagn. 2005; 7(5): 605-12. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60594-6.

- Grasmane A., Rots D., Vitina Z., Magomedova V., Gailite L. The association of FMR1 gene (CGG)n variation with idiopathic female infertility. Arch. Med. Sci. 2019; 17(5): 1303-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2019.85154.

- Rehnitz J., Alcoba D.D., Brum I.S., Dietrich J.E., Youness B., Hinderhofer K. et al. FMR1 expression in human granulosa cells increases with exon 1 CGG repeat length depending on ovarian reserve. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018; 16(1): 65. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12958-018-0383-5.

- Nowaczyk M.J., Waye J.S., Douketis J.D. DHCR7 mutation carrier rates and prevalence of the RSH/Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: where are the patients? Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006; 140(19): 2057-62. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.31413.

- Gruhn J.R., Zielinska A.P., Shukla V., Blanshard R., Capalbo A., Cimadomo D. et al. Chromosome errors in human eggs shape natural fertility over reproductive life span. Science. 2019; 365(6460): 1466-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aav7321.

- Capalbo A., Hoffmann E.R., Cimadomo D., Ubaldi F.M., Rienzi L. Human female meiosis revised: new insights into the mechanisms of chromosome segregation and aneuploidies from advanced genomics and time-lapse imaging. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2017; 23(6): 706-22. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmx026.

- Franasiak J.M., Forman E.J., Hong K.H., Werner M.D., Upham K.M., Treff N.R. et al. The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil. Steril. 2014; 101(3): 656-663.e1. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.004.

- McCoy R.C., Demko Z.P., Ryan A., Banjevic M., Hill M., Sigurjonsson S. et al. Evidence of selection against complex mitotic-origin aneuploidy during preimplantation development. PLOS Genet. 2015; 11(10): e1005601. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005601.

- Faridi R., Rehman A.U., Morell R.J., Friedman P.L., Demain L., Zahra S. et al. Mutations of SGO2 and CLDN14 collectively cause coincidental Perrault syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2017; 91(2): 328-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cge.12867.

- Caburet S., Arboleda V.A., Llano E., Overbeek P.A., Barbero J.L., Oka K. et al. Mutant cohesin in premature ovarian failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014; 370(10): 943-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1309635.

- Maddirevula S., Coskun S., Alhassan S., Elnour A., Alsaif H.S., Ibrahim N. et al. Female infertility caused by mutations in the oocyte-specific translational repressor PATL2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017; 101(4): 603-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.009.

- Chen B., Zhang Z., Sun X., Kuang Y., Mao X., Wang X. et al. Biallelic mutations in PATL2 cause female infertility characterized by oocyte maturation arrest. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017; 101(4): 609-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.018.

- Feng R., Yan Z., Li B., Yu M., Sang Q., Tian G. et al. Mutations in TUBB8 cause a multiplicity of phenotypes in human oocytes and early embryos. J. Med. Genet. 2016; 53(10): 662-71. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103891.

- Shafei R.A., Syrkasheva A.G., Romanov A.Y., Makarova N.P., Dolgushina N.V., Semenova M.L. Blastocyst hatching in humans. Russ. J. Dev. Biol. 2017; 48(1): 5-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S1062360417010106.

- Okutman Ö., Demirel C., Tülek F., Pfister V., Büyük U., Muller J. et al. Homozygous splice site mutation in ZP1 causes familial oocyte maturation defect. Genes (Basel). 2020; 11(4): 382. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/genes11040382.

- Syrkasheva A.G., Dolgushina N.V., Romanov A.Y., Burmenskaya O.V., Makarova N.P., Ibragimova E.O. et al. Cell and genetic predictors of human blastocyst hatching success in assisted reproduction. Zygote. 2017; 25(05): 631-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0967199417000508.

- Dai C., Chen Y., Hu L., Du J., Gong F., Dai J. et al. ZP1 mutations are associated with empty follicle syndrome: evidence for the existence of an intact oocyte and a zona pellucida in follicles up to the early antral stage. A case report. Hum. Reprod. 2019; 34(11): 2201-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dez174.

- Chen T., Bian Y., Liu X., Zhao S., Wu K., Yan L. et al. A recurrent missense mutation in ZP3 causes empty follicle syndrome and female infertility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017; 101(3): 459-65. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.001.

- Dai C., Hu L., Gong F., Tan Y., Cai S., Zhang S. et al. ZP2 pathogenic variants cause in vitro fertilization failure and female infertility. Genet. Med. 2019; 21(2): 431-40. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0064-y.

- Alazami A.M., Awad S.M., Coskun S., Al-Hassan S., Hijazi H., Abdulwahab F.M. et al. TLE6 mutation causes the earliest known human embryonic lethality. Genome. Biol. 2015; 16: 240. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0792-0.

- Sang Q., Li B., Kuang Y., Wang X., Zhang Z., Chen B. et al. Homozygous Mutations in WEE2 cause fertilization failure and female infertility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018; 102(4): 649-57. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.015.

- Zheng W., Zhou Z., Sha Q., Niu X., Sun X., Shi J. et al. Homozygous mutations in BTG4 cause zygotic cleavage failure and female infertility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020; 107(1): 24-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.05.010.

- Gardner D.K., Lane M. Culture and selection of viable blastocysts: a feasible proposition for human IVF? Hum. Reprod. Update. 1997; 3(4): 367-82. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humupd/3.4.367.

- Ковальская Е.В., Сыркашева А.Г., Романов А.Ю., Макарова Н.П., Долгушина Н.В. Современные представления о компактизации эмбрионов человека в условиях in vitro. Технологии живых систем. 2017; 14(1): 25-35. [Kovalskaya E.V., Syrkasheva A.G, Romanov A.Y, Makarova N.P., Dolgushina N.V. Modern views on the compaction of the human embryo in vitro. Technologies of Living Systems. 2017; 14(1): 25-35. (in Russian)].

- Tadros W., Lipshitz H.D. The maternal-to-zygotic transition: a play in two acts. Development. 2009; 136(18): 3033-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.1242/dev.033183.

- Tong Z.B., Gold L., Pfeifer K.E., Dorward H., Lee E., Bondy C.A. et al. Mater, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in mice. Nat. Genet. 2000; 26(3): 267-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/81547.

- Mahadevan S., Sathappan V., Utama B., Lorenzo I., Kaskar K., Van den Veyver I.B. Maternally expressed NLRP2 links the subcortical maternal complex (SCMC) to fertility, embryogenesis and epigenetic reprogramming. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7: 44667. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep44667.

- Esposito G., Vitale A.M., Leijten F.P.J., Strik A.M., Koonen-Reemst A.M.C.B., Yurttas P. et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) 6 is essential for oocyte cytoskeletal sheet formation and female fertility. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2007; 273(1-2): 25-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2007.05.005.

- Zheng P., Dean J. Role of Filia, a maternal effect gene, in maintaining euploidy during cleavage-stage mouse embryogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009; 106(18): 7473-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900519106.

- Gao Z., Zhang X., Yu X., Qin D., Xiao Y., Yu Y. et al. Zbed3 participates in the subcortical maternal complex and regulates the distribution of organelles. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018; 10(1): 74-88. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jmcb/mjx035.

- Yurttas P., Vitale A.M., Fitzhenry R.J., Cohen-Gould L., Wu W., Gossen J.A. et al. Role for PADI6 and the cytoplasmic lattices in ribosomal storage in oocytes and translational control in the early mouse embryo. Development. 2008; 135(15): 2627-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.1242/dev.016329.

- Titus S., Li F., Stobezki R., Akula K., Unsal E., Jeong K. et al. Impairment of BRCA1-related DNA double-strand break repair leads to ovarian aging in mice and humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013; 5(172): 172ra21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3004925.

Received 31.10.2024

Accepted 26.11.2024

About the Authors

Yana O. Martirosyan, Researcher at the F. Paulsen Research and Educational Center for ART, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, marti-yana@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9304-4410

Albina I. Kadaeva, PhD student, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, albina.karimovai@mail.ru

Anna S. Bolshakova, Geneticist, Department of Clinical Genetics of the Institute of Reproductive Genetics, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, +7(495)438-24-11, a_bolshakova@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7508-0899

Tatiana A. Nazarenko, Dr. Med. Sci., Head of the Institute of Reproductive Medicine, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, +7(495)438-13-41, t.nazarenko@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5823-1667

Almina M. Biryukova, PhD, Obstetrician-Gynecologist at the F. Paulsen Research and Educational Center for ART, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, 7(495)531-44-44, a_birukova@oparina4.ru

Ayuma N. Askeralieva, Clinical Resident, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, +7(913)175-31-44.