Characteristics of nutritional status in endometriosis and pain syndrome

Alieva P.M., Smetnik A.A., Moskvicheva Yu.B., Dumanovskaya M.R., Tabeeva G.I., Ermakova E.I., Fateeva E.M., Solopova A.E., Pavlovich S.V.

Objective: To analyze and evaluate the nutritional status and nutritional components with potential pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects in the diet of patients with endometriosis, as well as to study the possible relationship between the nutritional status and intensity of pain syndrome.

Materials and methods: The study included 58 patients aged 19 to 44 years with various forms of endometriosis and pain syndrome. The pain syndrome was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) and numeric rating scale (NRS). The nutritional status was assessed by frequency analysis using a computer program developed by the Scientific Research Institute of Nutrition of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, 2003–2006 (version 1.2.4). Statistical data processing was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.

Results: The comparison of the indicators with the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of substances showed a deficiency in such important micronutrients as magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca) (in groups with reduced BMI (rBMI) and high BMI (hBMI), iron, as well as vitamins B1, B2 and B3. Insufficient intake of legumes and whole grains was associated with a lower intake of magnesium in the patients of the study groups. Its values were lower than the median RDA (420 mg/day), namely: 190.1 mg in patients with rBMI, p<0.001 (RDA); 317.2 mg in patients with normal BMI (nBMI), 267.2 mg in patients with hBMI. Calcium intake was significantly decreased in women with rBMI and hBMI (610.8 mg and 798.2 mg, p<0.05; RDA of calcium is 1000 mg/day). Excessive consumption of processed meat products (sausages) and semi-finished products led to an increase in the consumption of table salt in patients of all three groups, which naturally caused an increase in sodium intake. There were no significant differences in the intensity of pain syndrome among the patients according to NRS and VAS.

Conclusion: The revealed characteristics of the nutritional status of patients with endometriosis demonstrate the potential for the development of novel therapeutic approaches to pain management. Dietary correction can become a component of complex pain therapy in this category of patients and contribute to improving their quality of life.

Authors’ contributions: Alieva P.M., Moskvicheva Yu.B., Dumanovskaya M.R. – developing the concept and design of the study; Alieva P.M., Moskvicheva Yu.B., Dumanovskaya M.R., Smetnik A.A. – collecting and processing the material, statistical data processing; Alieva P.M., Moskvicheva Yu.B., Fateeva E.M., Dumanovskaya M.R. – writing the text of the article; Tabeeva G.I., Ermakova E.I., Solopova A.E., Pavlovich S.V. – editing the article.

Conflicts of interest: Authors declare lack of the possible conflicts of interest.

Funding: The study was conducted without sponsorship.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: The patients signed informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Alieva P.M., Smetnik A.A., Moskvicheva Yu.B., Dumanovskaya M.R., Tabeeva G.I., Ermakova E.I., Fateeva E.M., Solopova A.E., Pavlovich S.V. Characteristics of nutritional status in endometriosis and pain syndrome.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (7): 92-102 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.131

Keywords

Endometriosis is a multifactorial chronic disease that affects up to 15% of women of reproductive age, according to various studies [1]. The prevalence of endometriosis can reach 70-80% in patients with chronic pelvic pain (CPP) [2]. The pain syndrome that is typical of this disease can manifest in the form of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and CPP. In addition to the above clinical manifestations, patients with endometriosis may experience atypical symptoms, such as neuropsychiatric disorders (depressive syndrome, fatigue, anxiety), digestive disorders (nausea, constipation, flatulence, cyclic bloating), and dysuric disorders, etc. [3, 4].

There are different theories about the occurrence of endometriosis. These theories, to some extent, can only partially explain the origin and development of the condition. Some of these theories include embryonic, lymphatic, immune, genetic ones, etc. The degree and severity of the disease can be influenced by various factors and epigenetic mechanisms, such as oxidative stress and inflammatory processes [5, 6]. Among the theories of endometriosis, the most widely accepted is the Sampson’s retrograde menstruation theory, which suggests that endometrial cells can be found outside the uterine cavity due to their passage through the fallopian tubes during menstruation. The adhesion and invasion of endometrial cells are believed to cause an inflammatory response, which locally attracts activated macrophages and leukocytes. The continuous growth of these foci is linked to immune system dysfunction and the induction of oxidative stress [7]. The release of hemoglobin and iron from erythrocytes activates macrophages, which leads to the production of inflammatory factors, including interleukins (IL-1, IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [8], and promotes the formation of reactive oxygen species. In healthy individuals, reactive oxygen species are normally produced during the oxygen metabolism process in the body, where a balance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant systems is maintained. An imbalance and an increase in the concentration of reactive oxygen species lead to cell proliferation [9] and excessive activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) under the influence of IL-6 and TNF-α. This, in turn, enhances the invasive and adhesive abilities of endometrial cells and stimulates angiogenesis and inflammation [10]. Studies have shown a correlation between endometriosis and increased levels of cytokines in the peritoneal fluid, suggesting a chronic inflammatory process in the peritoneum [10, 11]. Chronic inflammation stimulates free nerve endings activated by various damaging stimuli (nociceptors), alters nociceptive pathways and leads to peripheral and central sensitization. These processes play a significant role in the development of CPP in endometriosis [11].

According to the Russian clinical guidelines, the treatment of endometriosis depends on its severity and can be either conservative or surgical. The primary treatment involves laparoscopic removal of the lesions, followed by long-term therapy to prevent recurrence [12]. Conservative therapy includes progestins, combined hormonal contraceptives, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. Endometriosis treatment should aim to achieve the following goals: pain relief, suppression of the growth of endometriotic lesions, and prevention of the disease recurrence. Statistics show that the recurrence rate after surgical treatment reaches 50% within 5–7 years in case the patients do not receive treatment for endometriosis [13]. The systematic review that was conducted in 2017 and included 58 studies demonstrated the findings on the recurrence of pain syndrome after surgery or the end of drug therapy in 17–34% of women with endometriosis, and the lack of effect from therapy was observed in 5–59% of respondents [14].

Endometriosis therapy is long-term and requires an individual approach to each patient. Such factors as reproductive plans, the stage of the disease, age, and any concomitant conditions should all be taken into account when determining the best course of treatment. In addition, the drug tolerance and the quality of a woman’s life during treatment should be considered [15].

In addition to medical treatment, patients with endometriosis can be offered dietary changes, special diets, yoga, or physical exercise to help manage pain. These approaches are reflected in the international recommendations on endometriosis (European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, ESHRE, 2022) that focus on non-pharmacological methods for improving the quality of life of patients [16].

Nutrition is a recognized prognostic and modifiable factor that is directly linked to morbidity, duration, and quality of life [17]. There is evidence that various foods and their components affect the inflammatory processes in patients suffering from the diseases of the female reproductive system [18, 19]. Special attention is currently paid to the role of micronutrients (vitamins, minerals), which are involved in numerous biochemical pathways and are closely interconnected in complex metabolic chains. They participate in maintaining homeostasis, including all types of metabolism, namely redox balance, inflammatory pathways, hormonal regulation. The role of nutrition in the development and treatment of endometriosis has become a subject of interest, as several mechanisms of pathophysiology, such as inflammation and production of prostaglandins and interleukins, can be influenced by diet [20, 21].

Many of the food compounds exhibit antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, so dietary changes can help reduce the levels of inflammatory markers (e.g. IL-1, IL-6, or TNF-α, etc.), which are usually elevated in endometriosis [22]. Optimization of the diet affects the activity of prostaglandins, which are produced in large quantities in a chronic inflammatory response [23]. Research into the correlation between the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII, which evaluates the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory dietary factors and inflammation markers) and the risk of endometriosis revealed that increased intake of pro-inflammatory foods and a higher DII score (2.11 compared to 1.84, p=0.003) were associated with an increased risk of the disease [22].

Adding anti-inflammatory foods to the diet, such as legumes and calcium-rich dairy products, is linked to lower levels of inflammation markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and reactive oxygen species [23, 24].

Due to the lack of data on the long-term effects of nutrition and specific food components on endometriosis, there are currently no specific dietary recommendations for women with this condition. However, it can be assumed that by modifying the intake of certain nutrients, such as increasing anti-inflammatory substances and decreasing pro-inflammatory ones, there may be an opportunity to influence the severity of pain syndrome.

Therefore, the aim of the study is to analyze and evaluate the nutritional status and nutritional components with potential pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects in the diet of patients with endometriosis, as well as to study the possible relationship between the nutritional status and intensity of pain syndrome.

Materials and methods

The study included 58 patients aged 19 to 44 years with various forms of endometriosis: superficial endometriosis (SE) in combination with extragenital endometriosis (EE) (34/58), SE in combination with deep endometriosis (DE) (14/58), EE in combination with DE (10/58). The patients were selected on the basis of their complaints of long-term persistent pain syndrome, including dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia or CPP, as well as the results of clinical examinations, imaging tests (ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic organs) and a diagnosis confirmed by histological examination. The pain syndrome was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) and numeric rating scale (NRS). The nutritional status was assessed by frequency analysis using a computer program developed by the Scientific Research Institute of Nutrition of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, 2003–2006 (version 1.2.4). All patients signed an informed consent to participate in the study.

Statistical analysis

Due to the difference between the data and a normal distribution, the median (Me) and quartiles (Q1; Q3) were estimated when describing quantitative scales. The analysis of quantitative differences in two independent groups was carried out using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. The analysis of quantitative differences in three independent groups was carried out using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. The analysis of the significance of the differences between the mean and the standard values was carried out using the Student’s t-test.

The differences were found to be significant at the level of bilateral asymptotic significance of p≤0.05.

Results

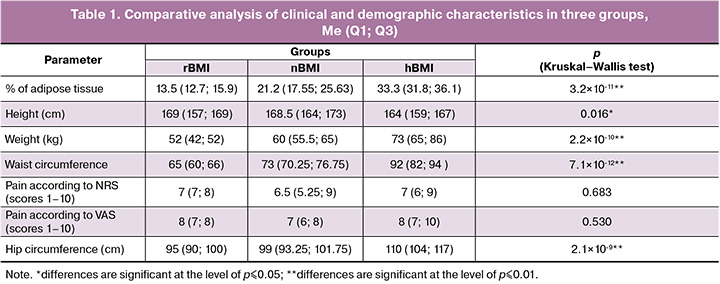

After body mass index (BMI) assessment, the patients were divided into three groups: patients with a normal BMI (nBMI, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) – 36/58 (62.1%), patients with a high BMI (hBMI, >24.9 kg/m2) – 16/58 (27.5%), patients with a reduced BMI (rBMI, <18.5 kg/m2) – 6/58 (10.3%). The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients in three groups are presented in Table 1.

There were no significant differences in the intensity of pain syndrome according to NRS and VAS among the patients of the three groups (p>0.05). The program assessed the following parameters: energy value of the diet, consumption of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), n-3 and n-6 PUFA, thiamine (vitamin B1), riboflavin (vitamin B2), niacin (vitamin B3/ PP). In all three study groups, deviations from the normal protein-to-fat-to-carbohydrate ratio (1:1:4) were observed (Table 1).

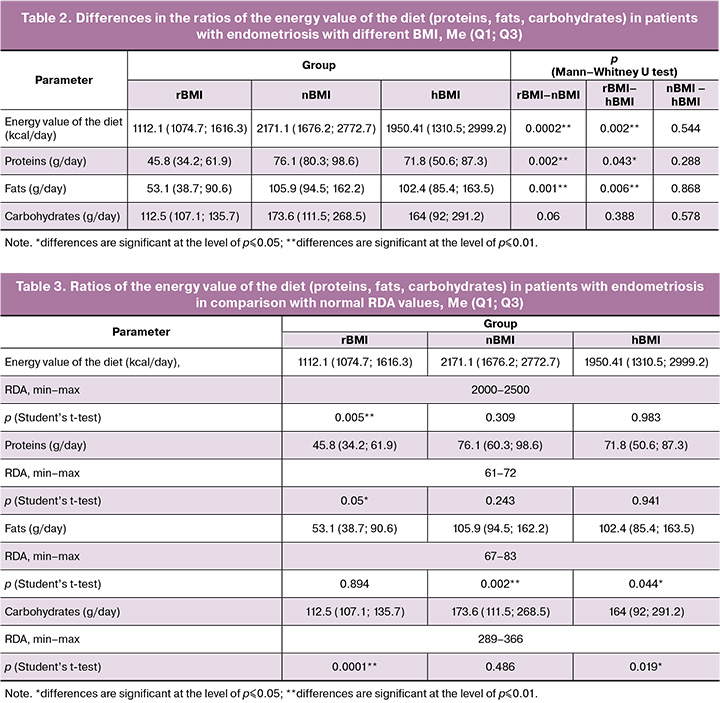

To calculate the values of the nutrients consumed, a comparative analysis of the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of the substances was conducted for each group [26]. The minimum threshold was chosen for ease of calculation. The mean parameters of the energy value of the diet were determined for each of the groups [Me (Q1; Q3)]: 1112.1 (1074.7; 1616.3) kcal/day for rBMI group; 2171.1 (1676.2; 2772.7) kcal/day for nBMI group; 1950.4 (1310.5; 2999.2) kcal/day for hBMI group. The energy value (caloric content) of a diet is the amount of energy the body receives from the food it consumes. At the same time, 1g of protein or carbohydrates provides 4 kcal, and 1g of fat provides 9 kcal. The energy value, number of consumed proteins, fats and carbohydrates in the groups with nBMI and hBMI did not differ significantly (p>0.05), however, these parameters were significantly lower in the group with rBMI than in the groups with nBMI (p≤0.01) and hBMI (p≤0.01) (Table 2).

It should be noted that the daily intake of carbohydrates and proteins did not differ significantly in the groups with rBMI and nBMI, and the amount of fat consumed was significantly higher in the groups with hBMI and nBMI (Table 3).

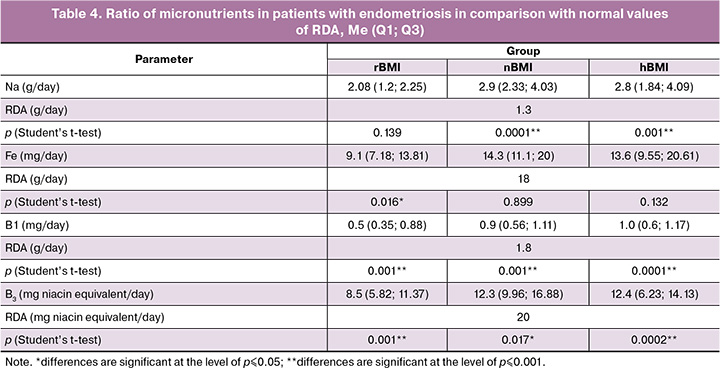

Insufficient intake of certain nutrients in comparison with RDA can affect the intensity of pain syndrome. Insufficient consumption of legumes and whole grains had a negative effect on magnesium intake in the patients of the study groups. Its values were lower than the median RDA (420 mg/day) and were 190.1 mg for the patients with rBMI, 317.2 mg for the patients with nBMI, 267.2 mg for the patients with hBMI, p<0.001 (RDA). Calcium intake was significantly reduced in patients with rBMI and hBMI (610.8 mg and 798.2 mg, respectively, p<0.05, in comparison with calcium value of 1000 mg/day in RDA), whereas the level of calcium consumed corresponded to the RDA parameter in patients with nBMI (1024.3 mg/day). Excessive consumption of processed meat products (sausages) and semi-finished products led to an increase in the consumption of table salt, which naturally resulted in increased sodium consumption (Table 4). Similar trends were noticed in iron consumption: the median intake was 9.1 mg/day in the group with rBMI, but it was 14.65 mg/day in the group with nBMI (p=0.001), and it was 13.6 mg/day in the group with hBMI (p=0.132). Patients with rBMI also had a reduced intake of B vitamins with antioxidant properties. The median intake of vitamin B3 (niacin) was 8.5 mg/day in the group with rBMI in comparison with RDA of 20 mg/day (p=0.001); it was significantly lower than in the groups with nBMI (12.3 mg/day, p=0.017) and hBMI (12.4 mg/day, p=0.0002).

The analysis also included an assessment of PUFA intake, in particular, essential omega-6 (n-6; linoleic and arachidonic acids) and omega-3 (n-3; alpha-linolenic, eicosapentaenoic, and docosahexaenoic acids) in patients with endometriosis. According to literature data, long-chain PUFAs (n-3 and n-6) are involved in the regulation of inflammation by modulating the biosynthesis of eicosanoids, including prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4, derivatives of arachidonic acid [27, 28]. The physiological need for PUFA in adults is 6-10% of their daily caloric intake. This amount should be distributed as follows: 5-8% for n-6 and 1-2% for n-3. The study did not reveal a deficiency of PUFA intake (n-6 and n-3) in patients of all three groups (rBMI, nBMI, hBMI). It is known that the predominance of n-6 over n-3 in the diet is associated with increased production of pro-inflammatory mediators. The anti-inflammatory properties of n-3 PUFA are due to their ability to serve as substrates for the synthesis of phospholipase A2 in cell membranes. This process helps to reduce the levels of arachidonic acid derivatives. In addition, n-3 PUFAs are precursors of resolvins and protectins, mediators that help resolve inflammation by reducing neutrophil infiltration [29]. There was an excess of n-6 PUFAs by 1.5 times compared to RDA in the group with high BMI. However, the average ratio of n-6 to n-3 in all three groups was 7.9:1, which is within the optimal range of 5-10:1.

Discussion

The energy value of the diet in the group with rBMI was lower than RDA in the group with rBMI (Table 3); it corresponded to RDA in the group with nBMI; and the energy value of the diet was more than 2500 kcal/day and exceeded RDA in 9/16 patients with hBMI. The energy value of the diet of the remaining 7/16 patients with hBMI corresponded to RDA or was slightly lower. This can be explained by the fact that when the patients were included in the study, they were following recommendations for normalizing their calorie intake by themselves. However, the reduction in the calorie content of their diet was mainly due to the reduction of carbohydrates, both simple (sugar, sweets, etc.) and complex (bread, pasta, grains, etc.). At the same time, the consumption of saturated fats (sausages, fatty meats, etc.) and unsaturated fats (vegetable oils) did not decrease. This indicates a lack of awareness among patients regarding proper nutrition (Table 1).

Despite the compliance with the recommended caloric intake (2000–2500 calories per day), 70% of the study participants regardless of their BMI showed an insufficient intake of several nutrients from food. This suggests a lack of dietary diversity, even with adequate energy value of the diet. Insufficient intake of certain nutrients from food can lead to their deficiency in the body, causing vitamin deficiency. This is due to primary defects that result from the impairment of biochemical and enzymatic processes. Subnormal vitamin levels represent an early preclinical stage of vitamin deficiency, which is usually characterized by impaired metabolic and physiological functions [30].

According to research data, the most common nutritional deficiencies observed in patients with endometriosis are related to iron, B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, and selenium [29, 31]. Our study included patients with pain syndrome, and all of them showed a deficiency in B vitamins (Table 4). It is believed that B vitamins are functionally interconnected in a metabolic chain as coenzymes, participating in key enzymatic reactions that help with carbohydrate metabolism, the production of amino acids, and the synthesis of neurotransmitters. These reactions are involved in the transmission of nerve impulses [31]. For example, reduced thiamine intake promotes lipogenesis and excessive fat accumulation, including visceral fat, which in turn activates adipocytes to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines. Prolonged insufficient consumption of vitamin B2 leads to a decrease in its activity and, consequently, a decrease in the development of active coenzyme forms of niacin and vitamin B6 [31].

In addition to B vitamins, magnesium and calcium play an important role in the transmission of nerve impulses [24, 32]. Magnesium affects contractile activity and relaxation of the uterine smooth muscles, and may also inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which is involved in the development of pain syndrome [33]. Despite the absence of a direct antinociceptive effect, magnesium acts as a physiological antagonist of calcium blocks NMDA receptors, preventing the penetration of Ca²⁺ ions into cells and thus modulating the processes of central sensitization that occur after nociceptive stimulation [34]. The effect of magnesium on potential-dependent calcium channels plays a key role in nociception mechanisms. Gök S. et al. demonstrated a decrease in pain intensity according to VAS, namely from 7.68±1.15 to 5.14±2.42 scores (p<0.001) in patients with primary dysmenorrhea after taking magnesium preparations for three menstrual cycles [33]. Our study found a statistically significant low magnesium intake in all three patient groups. In addition, patients with rBMI and hBMI demonstrated an insufficient intake of calcium-rich foods, such as milk, kefir, cottage cheese and cheese. This led to a deficiency in this mineral, which is important for intracellular signaling, muscle contraction, neurotransmission, as well as vasoconstriction and vasodilation. The systematic review conducted in 2021 that included 1,871 participants showed that isolated calcium intake, as well as its combination with magnesium or vitamin D, can help reduce the severity of primary dysmenorrhea [35].

The analysis of the diets of patients with endometriosis revealed an insufficient intake of foods that are rich in heme iron. Given the increased risk of iron deficiency anemia and latent iron deficiency, low iron intake is a significant risk factor, especially when surgical intervention is planned [36]. Iron deficiency can cause a longer hospital stay and increase the risk of postoperative complications, such as the development of iron deficiency anemia and slowing tissue regeneration. Therefore, it is recommended to screen for potential iron deficiency in all patients with endometriosis who plan surgical treatment [37].

The increased consumption of sodium chloride in individuals with endometriosis is noteworthy. A link has been found between excessive salt consumption and a higher prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) [38]. Excess salt can provoke inflammation and impair immune homeostasis, while following a salt–restricted diet (the Mediterranean diet, the DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), a low-protein diet option) shows positive results in achieving remission of IBD and manifestations of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), namely bloating and discomfort in the abdomen [39]. It is known that IBS is three times more common in patients with endometriosis, who often complain of bloating, pain and discomfort in the intestines [40].

Several studies have been conducted in recent years to find the relationship between nutrient intake and endometriosis-associated symptoms with patients’ quality of life. According to a recent systematic review, eliminating certain nutrients (e.g. gluten and soy) from the diet and adding others (e.g. n-3 and n-6 PUFA, some vitamins and minerals) were shown to reduce the severity of pain syndrome [41, 42]. The meta-analysis conducted in 2024 that involved 881 women with dysmenorrhea demonstrated that daily supplementation with n-3 PUFA for 2-3 months significantly reduced pain and the need for analgesics [43].

The large quantities of processed foods, such as sausages in the diet of the examined patients, resulted in an excessive intake of saturated fats. This corresponds to the literature data, which indicate the predominance of processed red meat, trans fats, and saturated fats in the diets of women with endometriosis, while the consumption of vegetables and fruits is reduced [21]. The importance of nutrition optimization is highlighted by a group of authors from the Netherlands, who found that dietary changes (e.g. increased intake of fruits, vegetables and ginger) contributed to symptom relief in 55% of patients with endometriosis [41, 42].

Our results show that the patients in the study followed a diet that can be described as a ‘Western diet’ (with an excess of fats, small amounts of vegetables and whole grains), which negatively affects the qualitative and quantitative composition of a healthy intestinal microbiota [44]. The intestinal microbiota plays an important role in immune regulation, and a decrease in its diversity can lead to a deterioration in vitamin B synthesis and the appearance of IBS-like symptoms.

Dietary changes and self-help strategies have shown to be effective in reducing pain for patients with IBS. Some of the symptoms of endometriosis are known to be mistaken for IBS (e.g. bloating, nausea and abdominal pain). The FODMAP diet, which stands for Fermentable Oligo-Di-Monosaccharides and Polyol, is a diet that involves reducing the intake of certain types of carbohydrates that have a high inflammatory potential. This diet has been shown to be effective in relieving pain symptoms and improving the quality of life [45]. The prospective study involving 60 patients with various forms of endometriosis and pain syndrome (more than 3 scores according to the VAS scale) showed that following a specific nutritional plan (a diet designed for patients with endometriosis, excluding foods with a high inflammatory index or following the FODMAP diet) for 6 months resulted in a reduction in pain syndrome [46]. Dietary changes were associated with a statistically significant reduction in bloating (VASbefore=8.0 (Me=3.8) scores, VASafter=3.0 (Me=4.5), p<0.001) and deep dyspareunia (VASbefore=4.5 (Me=6.0) scores, VASafter=1.0 (Me=4.0), p<0.05) compared to the control group; however, the indicators for dysmenorrhea were less significant (VASbefore=4.0 (Me=7.0) scores, VASafter=2.0 (Me=4.0), p=0.111). A patient with endometriosis can modify her diet in order to influence the pain syndrome and this way she can actively be involved in the treatment process and control her disease. This also increases her sense of responsibility for her health.

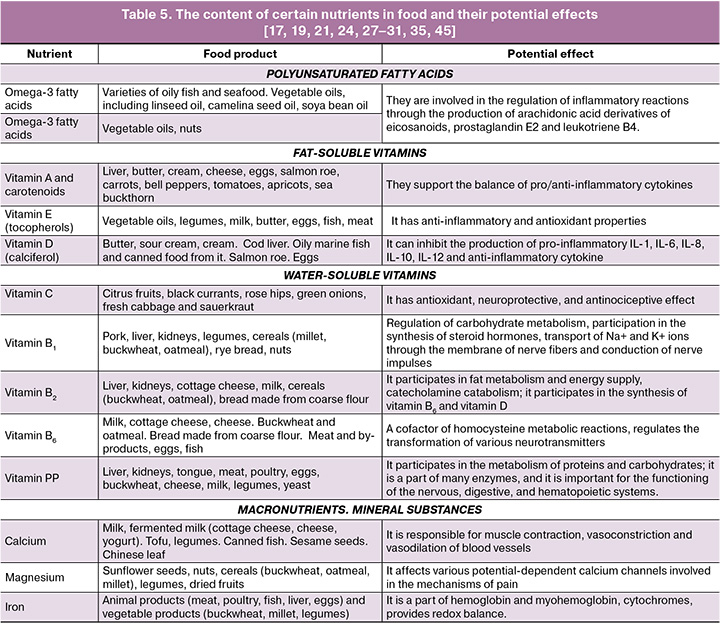

The study of nutritional characteristics in various forms of endometriosis remains relevant. A more detailed assessment of the nutritional characteristics depending on the form and duration of the disease, as well as therapeutic strategies, would optimize the nutrition of patients. New research data on the consumption of various nutrients suggests that a change in eating habits, such as the exclusion of foods with a high inflammatory index (Table 5) and the enrichment of the diet with anti-inflammatory nutrients, may affect the activity of inflammatory factors and prostaglandins. The elimination of the identified deficiencies in vitamins and minerals mentioned above can have a positive effect on pain and improve the quality of life for women with endometriosis.

The nutritional composition of a diet can be improved by correcting identified deficiencies and implementing specialized information resources for patients.

Conclusion

The study revealed a number of characteristics in the diet of patients with endometriosis and pain syndrome regardless of their BMI. Deficiencies of important micronutrients such as magnesium, calcium (in groups with both low and high BMI), iron, as well as vitamins B1, B2, and B3 were found in all groups. Excess sodium intake associated with the consumption of processed foods was observed in all three groups. The revealed characteristics of the nutritional status indicate the need to change the diet in patients with pain syndrome regardless of BMI and demonstrate the potential for the development of new approaches to managing pain syndrome. Dietary recommendations for changing nutrition can become a component of complex pain management in patients with endometriosis and contribute to improving their quality of life. Therefore, further research into the characteristics of the nutritional status of patients with endometriosis, depending on the duration, stage and form of the disease, remains relevant.

References

- Singh S., Soliman A.M., Rahal Y., Robert C., Defoy I., Nisbet P. et al. Prevalence, symptomatic burden, and diagnosis of endometriosis in Canada: cross-sectional survey of 30 000 women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2020; 42(7): 829-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2019.10.038

- Schliep K.C., Mumford S.L., Peterson C.M., Chen Z., Johnstone E.B., Sharp H.T. et al. Pain typology and incident endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2015; 30(10): 2427-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev147

- Leone Roberti Maggiore U., Bizzarri N., Scala C., Tafi E., Siesto G., Alessandri F. et al. Symptomatic endometriosis of the posterior cul-de-sac is associated with impaired sleep quality, excessive daytime sleepiness and insomnia: a case–control study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017; 209: 39-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.11.026

- Чернуха Г.Е., Пронина В.А. Коморбидность при эндометриозе и ее клиническое значение. Акушерство и гинекология. 2023; 1: 27-34. [Chernukha G.E., Pronina V.A. Endometriosis comorbidity and its clinical significance. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (1): 27-34 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.252

- Koninckx P.R., Ussia A., Adamyan L., Wattiez A., Gomel V., Martin D.C. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil. Steril. 2019; 111(2): 327-40. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.10.013

- Sampson J.A. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1927; 14(4): 422-69. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(15)30003-X

- Scutiero G., Iannone P., Bernardi G., Bonaccorsi G., Spadaro S., Voltaet C.A. et al. Oxidative stress and endometriosis: a systematic review of the literature. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017; 1: 7265238. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2017/7265238

- Van Langendonckt A., Casanas-Roux F., Donnez J. Oxidative stress and peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2002; 77(5): 861-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02959-x

- Malutan A.M., Drugan T., Costin N., Ciortea R., Bucuri C., Rada M.P. et al. Clinical immunology pro-inflammatory cytokines for evaluation of inflammatory status in endometriosis. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015; 40(1): 96-102. https://dx.doi.org/10.5114/ceji.2015.50840

- Berbic M., Schulke L., Markham R., Tokushige N., Russell P., Fraser I.S. Macrophage expression in endometrium of women with and without endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2009; 24(2): 325-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/den393

- Chronic Pelvic Pain: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 218. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 135(3): e98-e109. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003716

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Эндометриоз. М.; 2024. 32 с. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Endometriosis. Moscow; 2024. 32 p. (in Russian)].

- Адамян Л.В., Андреева Е.H. Эндометриоз и его глобальное влияние на организм женщины. Проблемы репродукции. 2022; 28(1): 54-64. [Adamyan L.V., Andreeva E.N. Endometriosis and its global impact on a woman’s body. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2022; 28(1): 54-64 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro20222801154

- Becker C.M., Gattrell W.T., Gude K., Singh S.S. Reevaluating response and failure of medical treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Fertil. Steril. 2017; 108(1): 125-36. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.004

- Лисовская Е.В., Хилькевич Е.Г., Чупрынин В.Д., Мельников М.В., Ипатова М.В. Качество жизни женщин с глубоким инфильтративным эндометриозом. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 3: 116-26. [Lisovskaya E.V., Khilkevich E.G., Chuprynin V.D., Melnikov M.V., Ipatova M.V. Quality of life for women with deep infiltrating endometriosis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020; (3): 116-26 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.3.116-126

- Becker C.M., Bokor A., Heikinheimo O., Horne A., Jansen F., Kiesel L. et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2022; 2: hoach009. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoac009

- Martinez-Gonzalez M.A., Martin-Calvo N. Mediterranean diet and life expectancy; beyond olive oil, fruits, and vegetables. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2016; 19(6): 401-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000316

- Zheng B., Shen H., Han H., Han T., Qin Y. Dietary fiber intake and reduced risk of ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Nutr. J. 2018; 17(1): 99. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0407-1

- Arab A., Karimi E., Vingrys K., Kelishadi M.R., Mehrabani S., Askari G. Food groups and nutrients consumption and risk of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr. J. 2022; 21(1): 58. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12937-022-00812-x

- Saguyod S.J.U., Kelley A.S., Velarde M.C., Simmen R. Diet and endometriosis-revisiting the linkages to inflammation. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2018; 10(2): 51-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2284026518769022

- Parazzini F., Viganò P., Candiani M., Fedele L. Diet and endometriosis risk: a literature review. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2013; 26(4): 323-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.12.011

- Liu P., Maharjan R., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Xu C. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and risk of endometriosis: a population-based analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023; 10: 1077915. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1077915

- Smolarz B., Szyłło K., Romanowicz H. Endometriosis: epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, treatment and genetics (review of literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021; 22(19): 10554. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910554

- Harris H.R., Chavarro J.E., Malspeis S., Willett W.C., Missmer S.A. Dairy-food, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D intake and endometriosis: a prospective cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013; 177(5): 420-30. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws247

- Nirgianakis K., Egger K., Kalaitzopoulos D.R., Lanz S., Bally L., Mueller M.D. Effectiveness of dietary interventions in the treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Reprod Sci. 2022; 29(1): 26-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s43032-020-00418-w

- Методические рекомендации МР 2.3.1.0253-21. Нормы физиологических потребностей в энергии и пищевых веществах для различных групп населения Российской Федерации (утв. Федеральной службой по надзору в сфере защиты прав потребителей и благополучия человека 22 июля 2021 г.). Доступно по: https://www.garant.ru/products/ipo/prime/doc/402716140/ [Methodological recommendations MR 2.3.1.0253-21. Norms of physiological needs for energy and nutrients for various groups of the population of the Russian Federation (approved by the Federal service for surveillance on consumer rights protection and human wellbeing on july 22, 2021). Available at: https://www.garant.ru/products/ipo/prime/doc/402716140/ (in Russian)].

- Hopeman M.M., Riley J.K., Frolova A.I., Jiang H., Jungheim E.S. Serum polyunsaturated fatty acids and endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2015; 22(9): 1083-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1933719114565030

- Parolini C. The role of marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in inflammatory-based disease: the case of rheumatoid arthritis. Mar. Drugs. 2023; 22(1): 17. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/md22010017

- Yalçın Bahat P., Ayhan I., Üreyen Özdemir E., İnceboz Ü., Oral E. Dietary supplements for treatment of endometriosis: a review. Acta Biomed. 2022; 93(1): e2022159. https://dx.doi.org/10.23750/abm.v93i1.11237

- Коденцова В.М. Витамины. 2-е изд. М.: Медицинское информационное агентство; 2023. 528 с. [Kodentsova V.M. Vitamins. 2nd ed. Moscow: Medical Information Agency; 2023. 528 p. (in Russian)].

- Roshanzadeh G., Sadatmahalleh S.J., Moini A., Mottaghi M.A., Rostami F. The relationship between dietary micronutrients and endometriosis: a case-control study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2023; 21(4): 333-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.18502/ijrm.v21i4.13272

- Hoşgörler F., Kızıldağ S., Ateş M., Argon A., Koç B., Kandis S. et al. The Chronic use of magnesium decreases VEGF levels in the uterine tissue in rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020; 196(2): 545-51. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12011-019-01944-8

- Gök S., Gök B. Investigation of laboratory and clinical features of primary dysmenorrhea: comparison of magnesium and oral contraceptives in treatment. Cureus. 2022; 14(11): e32028. https://dx.doi.org/10.7759/cureus.32028

- Woolf C.J., Thompson S.W.N. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991; 44(3): 293-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(91)90100-C

- Saei Ghare Naz M., Kiani Z., Fakari F.R., Ghasemi V., Abed M., Ozgoli G. The effect of micronutrients on pain management of primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J. Caring Sci. 2020; 9(1): 47-56. https://dx.doi.org/10.34172/jcs.2020.008

- Gete D.G., Doust J., Mortlock S., Montgomery G., Mishra G.D. Risk of iron deficiency in women with endometriosis: a population-based prospective cohort study. Womens Health Issues. 2024; 34(3): 317-24. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2024.03.004

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Клинические рекомендации. Железодефицитная анемия. М.; 2024. 36 с. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Clinical guidelines. Iron deficiency anemia. Moscow; 2024. 36 p. (in Russian)].

- Kuang R., O'Keefe S.J.D., de Rivers C.R.D.A., Koutroumpakis F., Binion D.G. Is salt at fault? Dietary salt consumption and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023; 29(1): 140-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac058

- Ruotolo A., Vannuccini S., Capezzuoli T., Pampaloni F. et al. Diet characteristics in patients with endometriosis. JEUD. 2025; 9: 100094. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeud.2024.100094

- Gete D.G., Doust J., Mortlock S., Montgomery G., Waller M., Mishra G.D. Associations between endometriosis and common symptoms: findings from the Australian longitudinal study on women's health. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023; 229(5): 536.e1-536.e20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.07.033

- Huijs E., Nap A. The effects of nutrients on symptoms in women with endometriosis: a systematic review. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2020; 41(2): 317-28. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.04.014

- Nap A., de Roos N. Endometriosis and the effects of dietary interventions: what are we looking for? Reprod. Fertil. 2022; 3(2): C14-C22. https://dx.doi.org/10.1530/RAF-21-0110

- Snipe R.M.J., Brelis B., Kappas C., Young J.K., Eishold L., Chui J.M. Omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids as a potential treatment for reducing dysmenorrhoea pain: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Diet. 2024; 81(1): 94-106. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12835

- Tomasello G., Mazzola M., Leone A., Sinagra E., Zummo G., Farina F. Nutrition, oxidative stress and intestinal dysbiosis: influence of diet on gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Biomed Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc. Czech Repub. 2016; 160(4): 461-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.5507/bp.2016.052

- Zhou L., Chen L., Li X., Li T., Dong Z., Wang Y.T. Effect of dietary patterns and nutritional supplementation in the management of endometriosis: a review. Front. Nutr. 2025; 12: 1539665. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2025.1539665

- van Haaps A.P., Wijbers J.V., Schreurs A.M.F., Vlek S., Tuynman J., De Bie B. et al. The effect of dietary interventions on pain and quality of life in women diagnosed with endometriosis: a prospective study with control group. Hum. Reprod. 2023; 38(12): 2433-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead214

Received 15.05.2025

Accepted 01.07.2025

About the Authors

Patimat M. Alieva, obstetrician-gynecologist, PhD student at the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, aalievapm@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0009-0007-1391-3211Antonina A. Smetnik, PhD, Head of the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, a_smetnik@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0627-3902

Yulia B. Moskvicheva, doctor-nutritionist at the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, yu_moskvicheva@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0114-4960

Madina R. Dumanovskaya, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, m_dumanovskaya@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7286-6047

Gyuzal I. Tabeeva, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, g_tabeeva@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1498-6520

Elena I. Ermakova, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, e_ermakova@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6629-051X

Evgeniya M. Fateeva, Resident, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, konat158@gmail.com,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3060-7113

Alina E. Solopova, Dr. Med. Sci., Leading Researcher at the Department of Radiation Diagnostics, Department of Visual Diagnostics, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P,

Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4; Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatology and Perinatal Medicine,

I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), 119991, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya, 8-2, a_solopova@oparina4.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4768-115X

Stanislav V. Pavlovich, PhD, Scientific Secretary, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4; Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatology and Reproductology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University),

119991, Russia, Moscow, Trubetskaya str., 8-22, s_pavlovich@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1313-7079

Corresponding author: Patimat M. Alieva, aalievapm@gmail.com