Immune and regenerative mechanisms in the pathogenesis of vulvovaginal atrophy: proteomic analysis of cervicovaginal fluid

Starodubtseva N.L., Nazarova N.M., Devyatkina A.R., Tokareva A.O., Kukaev E.N., Bugrova A.E., Brzhozovskiy A.G., Mezhevitinova E.A., Dovletkhanova E.R., Kepsha M.A., Frankevich V.E., Prilepskaya V.N., Sukhikh G.T.

Objective: Exploration of the relationship between clinical and anamnestic data, the severity of VVA, and the results of proteomic analysis of CVF to identify protein biomarkers associated with atrophic changes, inflammation, immune response, and tissue regeneration in the age group of 50–70 years.

Materials and methods: The methodological foundation of this study was a comprehensive analysis integrating the clinical and anamnestic data and proteomic analysis of cervicovaginal fluid (CVF) from patients with vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA). The study included 32 women aged 50–70 years with vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA). The comprehensive analysis included the clinical and anamnestic data, cytological examination, HPV genotyping, and analysis of the protein content of CVF. Semi-quantitative proteomic analysis (HPLC-MS/MS) including protein identification and annotation was performed using the MaxQuant and STRING software packages.

Results: Proteomic analysis of CVF identified specific protein profiles indicating activation of inflammatory processes, impaired tissue regeneration, and neurobiological mechanisms of pain sensitization. These profiles involved protein groups associated with blood microparticles and translocation of SLC2A4, both of which play an important role in occurrence of atrophic changes. Changes in PGAM1, PGAM2, and PGAM4 suggest impaired energy metabolism and the extracellular matrix synthesis, adversely affecting the proliferative activity of epithelial cells. Impaired glycine-serine metabolism reduces collagen and glutathione synthesis contributing to loss of tissue elasticity and increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Changes in synthesis of HSPA1A and HSPA1B are associated with impaired cellular adaptive responses and lead to accumulation of damaged proteins and enhanced apoptotic death of vaginal epithelial cells.

Conclusion: Proteomic analysis identified specific protein profiles indicating inflammatory activation, impaired tissue regeneration, and neurobiological pathways of pain sensitization.

Authors' contributions: The authors made substantial contributions to drafting the article and approved the final version before publication: Sukhikh G.T. – research concept and design; Nazarova N.M., Mezhevitinova E.A., Dovletkhanova E.R., Kepsha M.A. – data acquisition and processing; Starodubtseva N.L., Tokareva A.O., Kukaev E.N., Bugrova A.E., Brzhozovskiy A.G. – proteomic sample preparation and performance of proteomic analysis; Starodubtseva N.L., Tokareva A.O., Brzhozovskiy A.G., Kukaev E.N. – statistical data processing; Nazarova , N.M., Devyatkina A.R., Starodubtseva N.L., Tokareva A.O., Kukaev E.N., Bugrova A.E., Brzhozovskiy A.G. – manuscript writing; Frankevich V.E., Prilepskaya V.N. – editing and final approval of the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest: The authors confirm that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The study was carried out within the framework of the State Assignment No. № 12503063216-9 on the topic: “Development of a test system for early and minimally invasive diagnosis of HPV-associated precancerous and oncological diseases of the anogenital region in women of different ages using liquid biopsy”

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Centre for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia (Protocol No. 1 of January 30, 2025).

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients have signed informed consent for participation in the study and publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Starodubtseva N.L., Nazarova N.M., Devyatkina A.R., Tokareva A.O., Kukaev E.N., Bugrova A.E., Brzhozovskiy A.G., Mezhevitinova E.A., Dovletkhanova E.R., Kepsha M.A., Frankevich V.E., Prilepskaya V.N.,

Sukhikh G.T. Immune and regenerative mechanisms in the pathogenesis of vulvovaginal atrophy:

proteomic analysis of cervicovaginal fluid

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (12): 120-132 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.278

Keywords

Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) is one of the most common and clinically significant manifestations of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). The modern concept of GSM involves progressive changes in the vulvovaginal area, urethra and bladder that occur as a result of estrogen deficiency of various origins. GSM is a common condition that significantly reduces women's quality of life during the menopausal transition [1]. The main etiological factors include natural and surgical menopause, primary ovarian insufficiency, chemotherapy side effects, and hypothalamic amenorrhea [2]. Epidemiological data suggest that VVA symptoms as one of clinical manifestations of GSM are observed in 15% of women before the onset of menopause, while in the postmenopausal period the prevalence of VVA symptoms reaches up to 90% [3]. The high frequency of pathology is due to sharp decline in estrogen production (up to 95%), that is clinically manifested by vaginal dryness in 75% of patients, dyspareunia in 40% and dysuria in 30–40% of women [4]. The questionnaire-based REVIVE survey involved 3046 postpenopausal women, who reported VVA symptoms (38%) and dyspareunia (44%) [5]. Painful sexual intercourse had a significant impact on quality of life: 23% of women reported emotional distress, and 54% reported physical discomfort [5].

Estrogen deficiency leads to thinning of the stratified squamous epithelium, dysregulation of collagen and elastin synthesis, and the development of chronic inflammation and infiltration of immune competent cells into tissues [6]. In a number of cases, cytological evaluation showed that atrophic cervicitis was characterized by imbalance of the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio in the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium, dyskaryosis and hyperchromatic nuclei, that is often defined as cervical dysplasia, which is difficult to diagnose [7].

Along with estrogens, androgens contribute to the maintenance of genitourinary tissue structure and function [8]. Androgen receptors (ARs) are expressed in all layers of the vaginal epithelium (mucosa, submucosa, stroma, smooth muscle, vascular endothelium), indicating that testosterone has a direct effect on tissues of the genitourinary system [9]. The study showed that testosterone stimulates cell proliferation and regulates mucin production in the vagina [8]. It is noteworthy that although some androgen effects are generated by the action of aromatase, which converts testosterone to estradiol, androgen action is significantly influenced by direct binding of testosterone to the AR [10]. The research showed that a combination of estradiol and testosterone is necessary to maintain clitoral vascular reactivity and ensure an adequate response to sexual arousal [11].

Currently, proteomics is one of the most promising trends in the diagnosis and exploration of gynecological diseases. Proteomics denotes the large-scale study of the structure, function and dynamics of all proteins in the biological system [12]. Proteomic analysis of various body fluids is characterized by high sensitivity and specificity, and helps to identify the biomarkers for various pathologies. The proteomics techniques allow detailed analysis of proteomic changes in vaginal and urinary tract tissues, as well as in cervicovaginal fluid (CVF) and urine in various types of pathology of the female reproductive system [12–14].

Exploration of CVF is of particular interest. CVF plays a key role in maintaining homeostasis and providing immune protection of the lower genital tract. Cervical fluid represents a complex multicomponent system containing water, proteins, lipids, mucins, carbohydrates, amino acids, and inorganic ions [15].

CVF directly contacts the epithelium of the cervix and vagina and is an essential diagnostic material reflecting both the physiological state and pathological changes in the female reproductive system [16]. Numerous studies demonstrate significant changes in the proteomic profile of cervical fluid in various pathologies, including bacterial vaginosis, vaginitis, cervicitis, and neoplastic processes in the cervix [15]. Detailed characterization of changes in the CVF proteome is a promising current trend in research to develop personalized approaches to the diagnosis of the atrophic process and treatment.

The objective of the study was exploration of the relationship between clinical and anamnestic data, the severity of VVA, and the results of proteomic analysis of CVF to identify protein biomarkers associated with atrophic changes, inflammation, immune response, and tissue regeneration in the age group of 50-70 years.

Materials and methods

This single-center study was carried out at Scientific and Polyclinic Department of V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Centre for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia. The study included the clinical and laboratory examination of patients with VVA and subsequent proteomic analysis of CVF. The clinical and laboratory data were obtained at a single point of time within the framework of integrated clinical trial protocol. All patients red and signed informed consent for participation in the study. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the local Ethics Committee of V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Centre for Obstetrics, Gynecology, Ministry of Health of Russia (protocol No. 1 of January 30, 2025).

The sampling included objective-oriented recruitment of patients matching the primarily determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The patients were subsequently enrolled in the study upon seeking medical care and confirmation of matching criteria. The sample size of the pilot study was determined based on the technical capabilities for performance of proteomic analysis of CVF.

The study included 32 women with VVA, who met the inclusion criteria, such as age from 50 to 70 years, postmenopause for more than 2 years, atrophic smear pattern according to cytology test results, ability to follow the protocol requirements, signed informed consent. At the same time, the study excluded the patients, who took menopausal hormone therapy, had oncological diseases of reproductive organs, acute inflammatory diseases of specific and non-specific origin, impaired kidney, hepatic, and pulmonary function at the stage of decompensation, neuropsychiatric disorders (inability to follow the protocol).

Complete medical examination included collection of clinical and anamnestic data, determination of the degree of severity of VVA symptoms during gynecological exam, cytology tests, HPV typing and non-targeted proteomic analysis of CVF.

Cervical epithelium samples for cytological examination were collected using a cervical brush with detachable head in accordance with standard technique. Cytological evaluation of cervical smears was performed using the Bethesda System (2014).

Cervical scraping specimens for HPV genotyping were collected in tubes containing 0.9% sodium chloride and subsequently centrifuged. DNA fragments were detected and quantified using the HPV QUANT-21 quantitative REAL-TIME PCR Kit (DNA-Technology, Russia) on DT-964 thermocycler (DNA-Technology, Russia).

CVF samples were obtained by irrigation of the vagina and cervix were irrigated with saline before manipulation to minimize the risk of blood contamination. The samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove cellular debris. Then the supernatants were stored at -80°C. For non-targeted proteomic analysis of CVF, the proteins were renatured in 0.1 M (DTT) containing 8 M urine at Ph 8.5, alkylated with 0.55 M iodoacetamide and precipitated with 1% TCA solution in acetone. After tryptic hydrolysis, analysis of peptides was carried out in triplicate using Dionex UltiMate 3000 Nano HPLC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and the timsTOF Pro mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, USA). Chromatography analysis was done using 25 cm × 75 μm C18 column at 400 nl/min with a gradient of 2–37% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid). MS and MS/MS analysis was done in ddaPASEF mode (the capillary voltage 1500 V, dry gas flow 3.0 l/min with dry temperature of 180 °C). The scans were acquired in m/z range of 100–1700, ion mobility of 0.6–1.6 1/K₀ and linear collision energy gradient 20–59 eV [12, 14, 17].

The obtained data were processed using PEAKS Studio V. 11 (BSI, Canada) with precursor mass tolerance set to 20 ppm and fragment mass tolerance set to 0.05 Da. The search was performed using non-specific mode in the UniProt protein Knowledgebase (UniProtKB Homo Sapiens). Carbamidomethylation (C) was set as a fixed modification and oxidation (M) as a variable modification. The cutoff for the false discovery rate (FDR) was set at 0.1% for peptides and 1% for proteins. Identification of proteins was performed using at least one unique peptide.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using custom scripts written for statistical computing R 4.3.3. Statistical analysis included the proteins with at least two unique peptides, which were present in at least 70% of samples. To perform clustering analysis, protein normalization was implemented using the logarithm of the ratio between the total protein content in the sample and the average protein content in the study sample. Spectral clustering algorithm for Sub-Gaussian mixture models was used with the adaptive density-aware kernel. Clustering algorithm figured out division into two clusters. Principal component analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis heatmaps were used to visualize the dataset. The potential difference characterizing the proteins were determined in the resulting clusters using the Mann–Whitney U-test with significance level of 0.1. Normalization of the resulting protein levels was implemented using PEAKS Studio.

The Mann–Whitney U-test at significance level of p<0.01 was used to detect significant changes in protein markers in CVF in two isolated clusters. The additional criterion was the ratio levels between the clusters (fold change [18, 19]) greater than 2 or less than 0.5.

Bioinformatics analysis was performed using the STRING database with the threshold of false discovery rate at p<0.05 [20]. Gene Ontology annotation was used for protein description.

The clinical characteristics of patients in two clusters were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U-test for numerical parameters. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for categorical data. The threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.05. The numerical clinical parameters are presented as Me (Q1; Q3), where Me is the median, Q1 is the first quartile, and Q3 is the third quartile. The categorical clinical data are represented as the number of cases in the group and the proportion (%) of cases in the group.

Results and discussion

Non-targeted proteomic analysis of CVF in 32 patients with VVA identified 2075 proteins. Of them, 1412 proteins were identified using the “two peptide rule”; 297 proteins were detected in more than 70% of samples. The lowest albumin (ALB) variability (the relative variation of 50%) and the highest UDP-glucose-6-dehydrogenase (UGDH) variability (the relative variation of 11490%) was observed in patients.

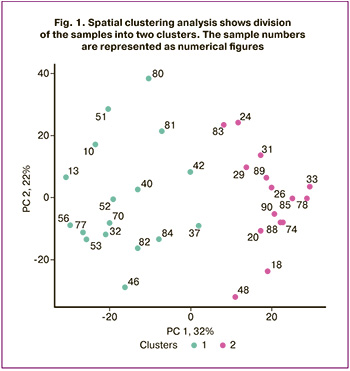

The samples of CVF from patients with VVA were divided into two protein clusters (Fig. 1).

The median age of patients in cluster 1 (n=17) was 57 years. According to the anamnestic data, 5/17 women (29%) had undergone prior surgical interventions for the cervix, including, conization, electrocoagulation, or excision of pathological lesions. Clinical assessment of VVA severity showed that vulvovaginal atrophy in 10/17 patients was manifested by epithelial thinning, high degree of tissue trauma, and reduced vaginal secretion (59%). Severe VVA was diagnosed in 7/17 women (41%). It was characterized by petechial hemorrhages and microcracks. Cytological results showed athrophic cervicovaginal smears, that were categorized as negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) in all 17 cases (100%). HPV genotyping results showed different high-risk HPV types in 8/17 women (47%): HPV 16, 33, 35, 39, 45, 52, 53, 56 and 73.

Colposcopy results showed that atrophic vulvovaginitis and/or cervicitis was in 17/17 patients (100%). It should be noted that visual inspection with acetic acid was less specific for this cohort of patients compared with women of reproductive age.

The median age of patients in cluster II (n=15) was 60 years. The anamnestic data showed that the number of surgical interventions for the cervix was statistically less significant – 3/15 (20%). Gynecological examination found VVA in 2/15 patients (13%), that was manifested by moderate epithelial thinning, dryness and reduced elasticity. Severe VVA was diagnosed in 13/15 patients (87%), that was characterized by epithelial thinning, petechial hemorrhages, and a high degree of tissue fragility.

Colposcopy results showed that atrophic cervicitis and/or atrophic vaginitis was in 15/15 patients (100%). Cervicovaginal smear cytology results confirmed the diagnosis of NILM with specific atrophic changes in all 15 cases (100%), that were similar to those found in group 1.

HPV genotyping results in cluster II showed the presence of different HPV types in 9/15 patients (60%). Among them, high-risk HPV types 31, 33, 45, 51, 53, 56, 66, 68, 73 and 82 were detected. There was no difference between the groups in the frequency of HPV infection. However, the patients with severe VVA experienced vulvovaginal traumas, that might indicate a high risk of persistent HPV infection and the development of neoplastic processes.

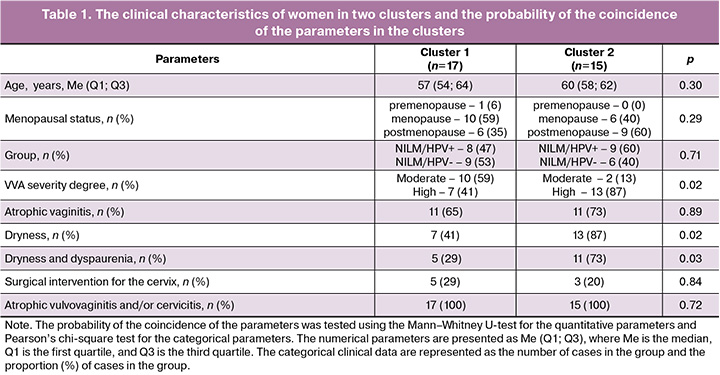

Analysis of the clinical characteristics showed significant differences in the prevalence of major VVA symptoms, which were identified by non-targeted proteomic analysis of CVF in the clusters. In cluster I, vaginal dryness was detected in 7/17 patients (41%), and dyspareunia in 5/17 patients (29%). In cluster II these indicators were significantly higher (p=0.02 and p=0.03, respectively). Vaginal dryness was found in 13/15 patients (87%), and dyspareunia in 11/15 women (73%) (Table 1). This difference indicated different severity levels of the condition or underlying pathogenetic processes in patients in group II.

Among 48 proteins of CVF grouped in two cluster samples (Fig. 2), low levels of cofilin-1 (CFL1), probable phosphoglycerate mutase 4 (PGAM4) and serpin A1/alpha 1-antitrypsin recombinant protein (SERPINA1) were detected, while the level of serotransferrin (TF) was high. Hemopexin (HPX) showed the lowest variability; the coefficient of variation (CV) was 62%. Whereas, myosin-9 (MYH9) showed the highest variability. The CV was 720%.

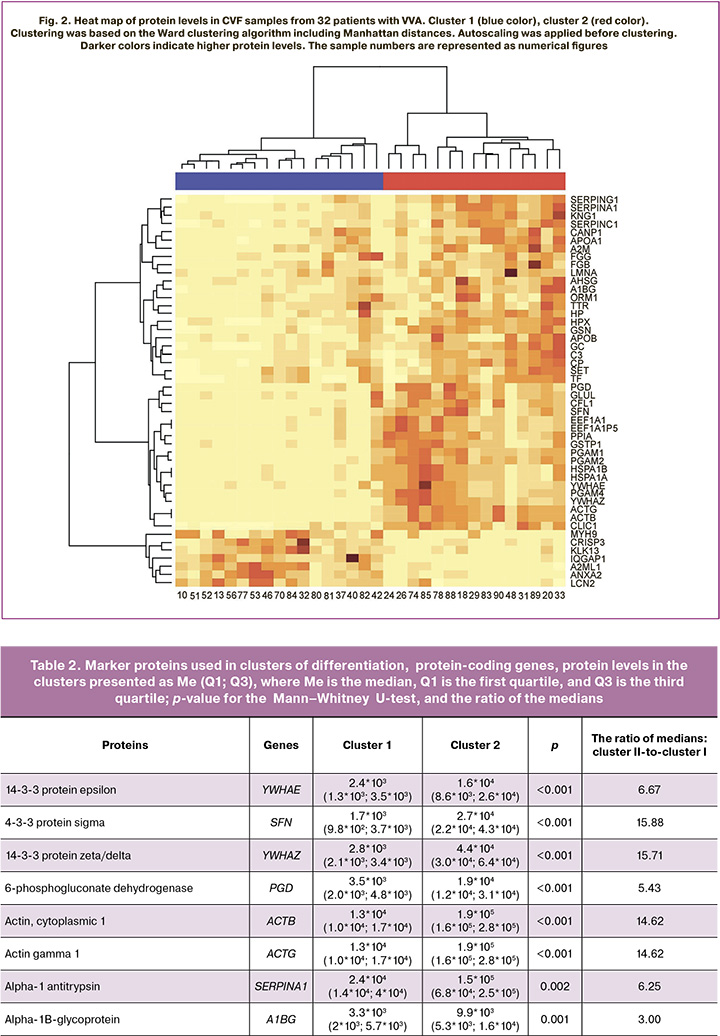

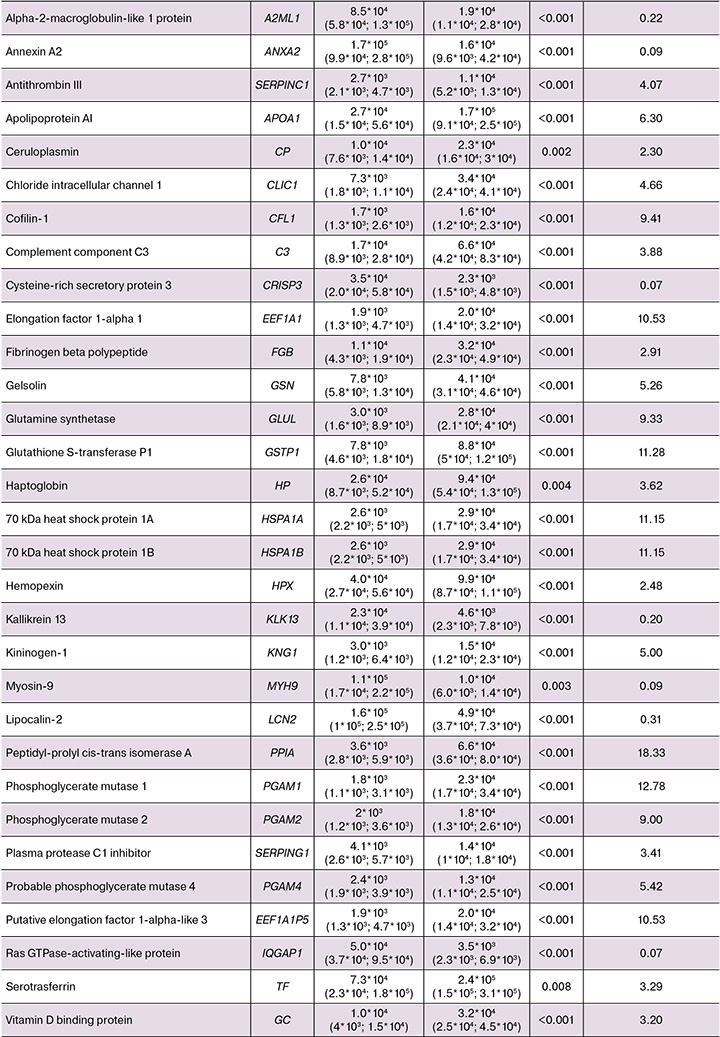

It should be noted that 39 proteins were found to be marker proteins (p<0.01, fold change >2 or fold change <0.5) in differentiaton of two identified clusters (Fig. 2, Table 2). Among them, significantly reduced levels of the following 7 proteins were observed: Ras GTPase-activating-like Protein (IQGAP1), alpha-2-macroglobulin-like 1 (A2ML1), annexin A2 (ANXA2), lipocalin-2 (LCN2), kallikrein 13 (KLK13), cysteine-rich secretory protein 3 (CRISP3), and myosin heavy chain 9 (MYH9) protein.

The previously conducted study by our research group [14] identified the proteins, which were also associated with dysplasia: ACTG1, C3, CRISP3, FGB, GSN, HPX, LCN2, SERPING1 и GC. It is noteworthy, that the changes in the levels of these proteins in dysplasia coincided with the changes in cluster 2 compared with the first cluster (Table 2).

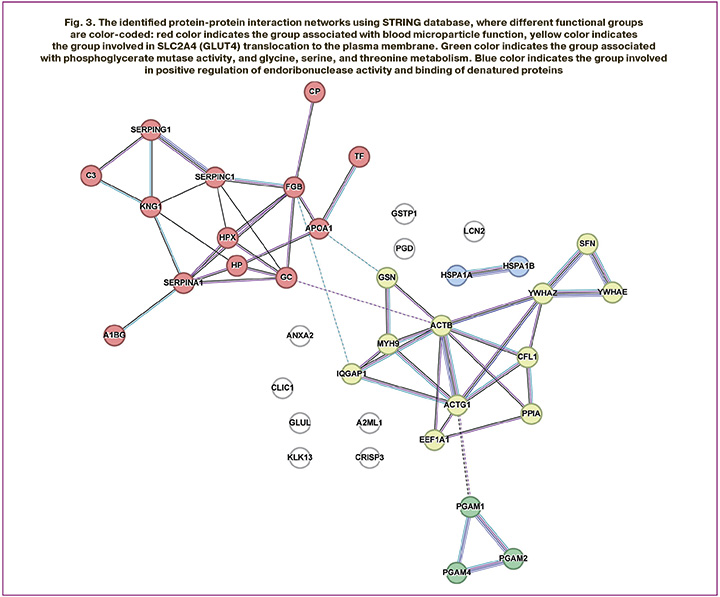

Analysis of protein content of CVF using STRING software showed that significantly different proteins formed 4 functional groups (Fig. 3). The largest groups were associated with blood microparticles and insulin-regulated facilitative glucose transporter (SLC2A4) translocation to the plasma membrane. The third group of proteins, including phosphoglycerate mutase 1 (PGAM1), phosphoglycerate mutase 2 (PGAM2), and probable phosphoglycerate mutase 4 (PGAM4), was associated with phosphoglycerate mutase activity, as well as with glycine, serine, and threonine the metabolism. The fourth functional group formed by heat shock 70 kDa proteins 1A and 1B (HSPA1A and HSPA1B) was involved in positive regulation of endoribonuclease activity and binding of denatured proteins.

The obtained results enable to fundamentally reexamine the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying VVA. With decreased estrogen level, enrichment of the functional group of proteins associated with blood microparticles and SLC2A4 translocation demonstrates impaired glucose translocation to the plasma membrane of vaginal epithelial cells [21, 22]. This leads to energy deficiency and tissue atrophy. The presence of microparticles (microvesicles) in the blood [23] is associated with chronic subclinical inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [23], that leads to additional worsening of tissue trophism in the vulvovaginal area.

Activity of phosphoglycerate mutase PGAM1, PGAM2, and PGAM4, and relationship between them and glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism [24, 25] indicate imbalanced energy metabolism and the synthesis of structural components of the extracellular matrix. A decrease in activity of these enzymes can lead to lactate accumulation and occurrence of local acidosis [25], that has a negative impact on epithelial cell proliferative activity [26]. In addition, impaired glycine and serine metabolism can reduce collagen and glutathione synthesis, that contributes to the loss of tissue elasticity and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress [27].

The functional group including the heat shock proteins HSPA1A and HSPA1B is involved in regulation of endoribonuclease activity and binds denatured proteins [28] and can be associated with impaired cellular adaptation to stress. Reduced expression of this proteins in the presence of estrogen deficiency can lead to the accumulation of damaged proteins and increased apoptotic cell death of vaginal epithelial cells [29]. Thus, the altered protein spectrum of CVF reflects not only morphological atrophy, but also a cascade of complex pathological processes that require an innovative approach to patient management going beyond the traditional methods.

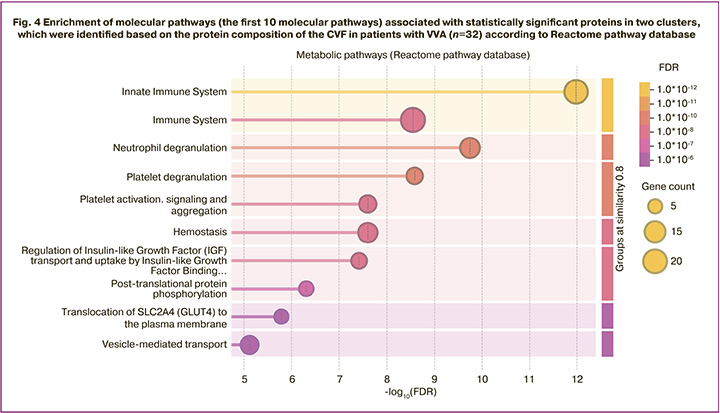

Furthermore, the following proteins: MYH9, C3, alpha-1B-glycoprotein (A1BG), IQGAP1, SERPING1, FGB, elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (EEF1A1), ANXA2, haptoglobin (HP), PGAM1, LCN2, GSN, HSPA1B, glutathione S-transferase P (GSTP1), CRISP3, SERPINA1, peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A (PPIA), CFL1, gamma-actin (ACTG), actin cytoplasmic 1 (ACTB) and 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta (YWHAZ) significantly enrich immune system signaling pathways (Fig. 4). This observation is consistent with the results of the study by Geert A.A. Van Raemdonck’s research group reporting that the proteome of CVF showed increased fractions of immunological and extracellular proteins [30]. Immune response plays a crucial role in chronic inflammation or infection [31].

Analysis of heat map of protein levels (Fig.3) found significantly increased levels of most proteins in cluster II. In contrast, increased protein expression in cluster I was observed only for the limited set of proteins (MYH9, IQGAP1, ANXA2, LCN2, CRISP3). Given that immune response plays a key role in maintaining homeostasis in chronic inflammation and infection [31], the data obtained in our study may indicate activation of immune processes in response to pathological changes in tissues.

Since vaginal atrophy is accompanied by inflammation, this suggests that regulating the immune system is not sufficient to weaken the inflammatory response. [32]. Also, changes in gene expression levels may play a role in occurrence of vaginal bleeding in women [33]. The immune response caused by inflammatory processes in atrophic tissues can enhance expression of genes involved in coagulation and fibrinolysis [34]. High frequency and, probably, high degree of severity of dyspaurenia

can be explained by the complex interaction of structural and neurobiological changes

[35]. The vaginal epithelium has a dense network of sensory nerve endings. Physiologically, estrogens modulate their sensitivity by suppressing the excessive transmission of pain signals [36, 37]. Hypoestrogenism can increase the density of sympathetic and sensory innervation, leading to vasoconstriction, vaginal dryness and pain [38]. Also, testosterone deficiency leads to reduced nerve density and neurotransmitter imbalance, that can which can increase the symptoms symptoms of dyspareunia [8]. In parallel, atrophic processes in the epithelium and chronic subclinical inflammation lead to impairment of the protective functions, that contributes to exposure of nerve endings to any mechanical, chemical or temperature irritants [39, 40]. It should be noted that at the molecular level, the pathological processes especially manifested by high frequency of dyspareunia in patients in cluster II, can be mediated and enhanced by hyperexpression of proteins, which are involved in the transmission of pain signals, neuroinflammation and nociceptor sensitization [41–45]. Thus, kininogen-1 (KNG1) protein plays a key role in direct activation of pain receptors and the development of hyperalgesia. Overexpression of KNG1, a precursor of bradykinin, directly stimulates and sensitizes nociceptors, abnormally increasing sensitivity to pain

[41]. C3 protein plays an important role in immune response, and can be indirectly involved in activation of nociceptors (causing smooth muscle contraction, increasing vascular permeability and causing histamine release from mast cells and basophilic leukocytes) [42]. Chloride intracellular channel 1 (CLIC1) protein regulates ion channels and is potentially involved in mechanisms of hyperalgesia via alterations of electrophysiological properties of neurons [43]. Additionally, glutamine synthase (GLUL) involved in regulation of neurotransmitter balance [44] and ANXA2 involved in modulation of intracellular signaling) [45] contribute to pathological state.

Thus, high prevalence of dyspareunia in patients in cluster II may be due to not only structural atrophy, but also due to specific hyperexpression of proinflammatory proteins and proteins accelerating pain sensitivity. Protein hyperexpression is destructive, since inflammation and tissue degradation stimulate proliferation of sensory fibers and their sensitization, primarily through bradykinin and complement-dependent mechanisms, that are clinically manifested as severe dyspareunia.

The results of proteomic analysis indicate the importance of a complex approach to exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying VVA. This approach can give us insights into the role of various proteins in immune and regenerative processes and facilitate the development of new therapeutic strategies aimed at improving patients’ quality of life.

Based on proteomic analysis, we propose a classification according to the degree of adaptive response in tissues in VVA. Molecular markers associated with regeneration and inflammation were used for classification, that helped to distinguish adaptive and non-adaptive forms of the atrophic process (Table 3). This classification demonstrates not only the severity of VVA, but also the relationship between the severity of dyspareunia and compensatory capacity, synthesis of pro-inflammatory proteins and proteins that enhance pain sensitivity. It also demonstrates the absence of relationship between dyspareunia and dryness, the most common symptom in VVA.

Conclusion

Proteomic analysis of CVF identified specific protein profiles indicating activation of inflammatory processes, impaired tissue regeneration, and neurobiological mechanisms of pain sensitization. Identification of pro-inflammatory proteins and proteins that enhance pain sensitivity, correlating with the severity of dyspareunia was of particular significance. This indicates the molecular mechanisms underlying chronic pain in postmenopausal women with VVA, that makes it possible to consider it as a complex pathological process.

References

- Ярмолинская М.И., Колошкина А.В. Алгоритм диагностики и лечения генитоуринарного менопаузального синдрома. Акушерство и гинекология. 2024; 9 (Приложение): 22-36. [Yarmolinskaya M.I., Koloshkina A.V. Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024; 9 (Suppl.): 22-36 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.181

- Lev-Sagie A. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy: physiology, clinical presentation, and treatment considerations. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015; 58(3): 476-91. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000126

- Оразов М.Р., Силантьева Е.С., Радзинский В.Е., Михалева Л.М., Хрипач Е.А., Долгов Е.Д. Вульвовагинальная атрофия в пери- и постменопаузе: актуальность проблемы и влияние на качество жизни. Гинекология. 2022; 24(5): 408-12. [Orazov M.R., Silantyeva E.S.,Radzinsky V.E., Mikhaleva L.M., Khripach E.A., Dolgov E.D. Vulvovaginal atrophy in the peri- and post-menopause: relevance and impact on quality of life. Gynecology. 2022; 24(5): 408-12 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.26442/20795696.2022.5.201854

- Reed S.D. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024; 67(1): 1-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/grf.0000000000000843

- Freedman M.A. Perceptions of dyspareunia in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: findings from the REVIVE survey. Women’s Heal. (Lond). 2014; 10(4): 445-54. https://dx.doi.org/10.2217/whe.14.29

- Li S., Herrera G.G., Tam K.K., Lizarraga J.S., Beedle M.T., Winuthayanon W. Estrogen action in the epithelial cells of the mouse vagina regulates neutrophil infiltration and vaginal tissue integrity. Sci. Rep. 2018; 8(1): 11247. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29423-5

- Li Y., Shoyele O., Shidham V.B. Pattern of cervical biopsy results in cases with cervical cytology interpreted as higher than low grade in the background with atrophic cellular changes. Cytojournal. 2020; 17: 12. https://dx.doi.org/10.25259/cytojournal_82_2019

- Traish A.M., Vignozzi L., Simon J.A., Goldstein I., Kim N.N. Role of androgens in female genitourinary tissue structure and function: implications in the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Sex. Med. Rev. 2018; 6(4): 558-71. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.03.005

- Bertin J., Dury A.Y., Ouellet J., Pelletier G., Labrie F. Localization of the androgen-synthesizing enzymes, androgen receptor, and sex steroids in the vagina: possible implications for the treatment of postmenopausal sexual dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2014; 11(8): 1949-61. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12589

- Witherby S., Johnson J., Demers L., Mount S., Littenberg B., Maclean C.D. et al. Topical testosterone for breast cancer patients with vaginal atrophy related to aromatase inhibitors: a phase I/II study. Oncologist. 2011; 16(4): 424-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0435

- Comeglio P., Cellai I., Filippi S., Corno C., Corcetto F., Morelli A. et al. Differential effects of testosterone and estradiol on clitoral function: an experimental study in rats. J. Sex. Med. 2016; 13(12): 1858-71. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.10.007

- Франкевич В.Е., Назарова Н.М., Довлетханова Э.Р., Гусаков К.И., Кононихин А.С., Бугрова А.Е., Бржозовский А.Г., Прилепская В.Н., Стародубцева Н.Л., Сухих Г.Т. Протеомный анализ цервиковагинальной жидкости при применении активированной глицирризиновой кислоты у пациенток с ВПЧ-ассоциированными поражениями шейки матки. Акушерство и гинекология. 2022; 5: 109-17. [Frankevich V.E., Nazarova N.M., Dovlethanova E.R., Gusakov K.I. , Kononikhin A.S., Bugrova A.E., Brzhozovskiy A.G., Prilepskaya V.N., Chagovets V.V., Starodubtseva N.L., Sukhikh G.T. Proteomic analysis of cervicovaginal fluid of patients with HPV-associated cervical lesions treated with activated glycyrrhizic acid. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; (5): 109-17 (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.5.109-117

- Зардиашвили М.Д., Франкевич В.Е., Назарова Н.М., Бугрова А.Е., Кононихин А.С., Бржозовский А.Г., Стародубцева Н.Л., Асатурова А.В., Сухих Г.Т. Характеристика изменений протеомного состава цервиковагинальной жидкости при заболеваниях шейки матки, ассоциированных с ВПЧ-инфекцией. Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 4: 88-94. [Zardiashvili M.D., Frankevich V.E., Nazarova N.M., Bugrova A.E., Kononikhin A.S., Brhozovsky А.G., Starodubtseva N.L., Asaturova A.V., Sukhikh G.T. Proteomic composition of cervicovaginal fluid in cervical diseases associated with HPV infection. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017; (4): 88-94 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.4.88-94

- Starodubtseva N.L., Brzhozovskiy A.G., Bugrova A.E., Kononikhin A.S., Indeykina M.I., Gusakov K.I. et al. Label-free cervicovaginal fluid proteome profiling reflects the cervix neoplastic transformation. J. Mass Spectrom. 2019; 54(8): 693-703. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jms.4374

- Mukherjee A., Pednekar C.B., Kolke S.S., Kattimani M., Duraisamy S., Burli A.R. et al. Insights on proteomics-driven body fluid-based biomarkers of cervical cancer. Proteomes. 2022; 10(2): 13. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/proteomes10020013

- Vagios S., Mitchell C.M. Mutual preservation: a review of interactions between cervicovaginal mucus and microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021; 11: 676114. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.676114

- Starodubtseva N.L., Brzhozovskiy A.G., Bugrova A.E., Kononikhin A.S., Gusakov K.I., Nazarova N.M. et al. Characteristics of dynamic changes in proteomic composition of cervicovaginal fluid in cervical diseases associated with HPV infection. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 7: 111-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.7.111-116

- Liu D., Zhao L., Jiang Y., Li L., Guo M., Mu Y. et al. Integrated analysis of plasma and urine reveals unique metabolomic profiles in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies subtypes. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022; 13(5): 2456-72. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13045

- Ji S., Liu Y., Yan L., Zhang Y., Li Y., Zhu Q. et al. DIA-based analysis of the menstrual blood proteome identifies association between CXCL5 and IL1RN and endometriosis. J. Proteomics. 2023; 289: 104995. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2023.104995

- Szklarczyk D., Kirsch R., Koutrouli M., Nastou K., Mehryary F., Hachilif R. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51(D1): D638-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1000

- Huang S., Czech M.P. The GLUT4 glucose transporter. Cell Metab. 2007; 5(4): 237-52. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.006

- Amabebe E., Anumba D.O.C. The vaginal microenvironment: the physiologic role of Lactobacilli. Front. Med. 2018; 5: 181. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00181

- Vanhoutte P.M., Shimokawa H., Feletou M., Tang E.H.C. Endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease – a 30th anniversary update. Acta Physiol. 2017; 219(1): 22-96. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apha.12646

- Locasale J.W. Serine, glycine and one-carbon units: cancer metabolism in full circle. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013; 13(8): 572-83. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc3557

- Hitosugi T., Zhou L., Elf S., Fan J., Kang H.B., Seo J.H. et al. Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 coordinates glycolysis and biosynthesis to promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2012; 22(5): 585-600. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.020

- Walenta S., Wetterling M., Lehrke M., Schwickert G., Sundfør K., Rofstad E.K. et al. High lactate levels predict likelihood of metastases, tumor recurrence, and restricted patient survival in human cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 2000; 60(4): 916-21

- Amelio I., Cutruzzolá F., Antonov A., Agostini M., Melino G. Serine and glycine metabolism in cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014; 39(4): 191-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.004

- Rosenzweig R., Nillegoda N.B., Mayer M.P., Bukau B. The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019; 20(11): 665-80. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0133-3

- Voss M.R., Stallone J.N., Li M., Cornelussen R.N.M., Knuefermann P., Knowlton A.A. Gender differences in the expression of heat shock proteins: the effect of estrogen. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003; 285(2): H687-92. https://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.01000.2002

- Zegels G., Van Raemdonck G.A.A., Tjalma W.A.A., Van Ostade X.W.M. Use of cervicovaginal fluid for the identification of biomarkers for pathologies of the female genital tract. Proteome Sci. 2010; 8: 63. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-5956-8-63

- Jeyakumari P., Shakeela G. The role of the immune system in maintaining homeostasis. J. Biomed. Pharm. Res. 2025; 14(2): 54-65. https://dx.doi.org/10.32553/jbpr.v14i2.1258

- Chen L., Deng H., Cui H., Fang J., Zuo Z., Deng J. et al. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 2018; 9(6): 7204-18. https://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23208

- Torelli F.R., Rodrigues-Peres R.M., Monteiro I., Lopes-Cendes I., Bahamondes L., Juliato C.R.T. Gene expression associated with unfavorable vaginal bleeding in women using the etonogestrel subdermal contraceptive implant: a prospective study. Sci. Rep. 2024; 14(1): 11062. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61751-7

- Wilhelm G., Mertowska P., Mertowski S., Przysucha A., Strużyna J., Grywalska E. et al. The crossroads of the coagulation system and the immune system: interactions and connections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023; 24(16): 12563. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612563

- Mwaura A.N., Marshall N., Anglesio M.S., Yong P.J. Neuroproliferative dyspareunia in endometriosis and vestibulodynia. Sex. Med. Rev. 2023; 11(4): 323-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/sxmrev/qead033

- Li T., Ma Y., Zhang H., Yan P., Huo L., Hu Y. et al. Estrogen replacement regulates vaginal innervations in ovariectomized adult virgin rats: a histological study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017; 2017: 7456853. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2017/7456853

- Mónica Brauer M., Smith P.G. Estrogen and female reproductive tract innervation: cellular and molecular mechanisms of autonomic neuroplasticity. Auton. Neurosci. 2015; 187: 1-17. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2014.11.009

- Ting A.Y., Blacklock A.D., Smith P.G. Estrogen regulates vaginal sensory and autonomic nerve density in the rat. Biol. Reprod. 2004; 71(4): 1397-404. https://dx.doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.104.030023

- Beck L.A., Cork M.J., Amagai M., De Benedetto A., Kabashima K., Hamilton J.D. et al. Type 2 inflammation contributes to skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. JID Innov. 2022; 2(5): 100131. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.xjidi.2022.100131

- Takahashi S., Ishida A., Kubo A., Kawasaki H., Ochiai S., Nakayama M. et al. Homeostatic pruning and activity of epidermal nerves are dysregulated in barrier-impaired skin during chronic itch development. Sci. Rep. 2019; 9(1): 8625. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44866-0

- Falsetta M.L., Foster D.C., Woeller C.F., Pollock S.J., Bonham A.D., Haidaris C.G. et al. A role for bradykinin signaling in chronic vulvar pain. J. Pain. 2016; 17(11): 1183-97. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.07.007

- Thangam E.B., Jemima E.A., Singh H., Baig M.S., Khan M., Mathias C.B. et al. The role of histamine and histamine receptors in mast cell-mediated allergy and inflammation: the hunt for new therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2018; 9: 1873. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01873

- Cai Y., Li J., Fan K., Zhang D., Lu H., Chen G. Downregulation of chloride voltage-gated channel 7 contributes to hyperalgesia following spared nerve injury. J. Biol. Chem. 2024; 300(10): 107779. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107779

- Albrecht J., Sidoryk-Wȩgrzynowicz M., Zielińska M., Aschner M. Roles of glutamine in neurotransmission. Neuron Glia Biol. 2010; 6(4): 263-76. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1740925X11000093

- Yamanaka H., Kobayashi K., Okubo M., Noguchi K. Annexin A2 in primary afferents contributes to neuropathic pain associated with tissue type plasminogen activator. Neuroscience. 2016; 314: 189-99. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.11.058

Received 02.10.2025

Accepted 19.12.2025

About the Authors

Natalia L. Starodubtseva, PhD (Bio), Head of the Laboratory of Clinical Proteomics, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, n_starodubtseva@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6650-5915Niso M. Nazarova, Dr. Med. Sci., Leading Researcher, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, n_nazarova@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9499-7654

Anastasia R. Devyatkina, obstetrician-gynecologist, PhD student, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, grinasta26@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1742-7555

Alisa O. Tokareva, PhD (Phys.-Math.), Specialist at the Laboratory of Clinical Proteomics, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia, alisa.tokareva@phystech.edu, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5918-9045

Evgenii N. Kukaev, PhD (Phys.-Math.), PhD, Senior Researcher at the Laboratory of Clinical Proteomics, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia; Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, e_kukaev@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8397-3574

Anna E. Bugrova, PhD (Bio), Senior Researcher at the Laboratory of Proteomics of Human Reproduction, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia; Senior Researcher, Laboratory of Neurochemistry, Emanuel Institute of Biochemical Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, a_bugrova@oparina4.ru

Alexander G. Brzhozovskiy, PhD (Bio), Senior Researcher at the Laboratory of Proteomics of Human Reproduction, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997; Junior Researcher at the Laboratory of Mass Spectrometry,

Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, agb.imbp@gmail.com

Elena A. Mezhevitinova, Dr. Med. Sci., Leading Researcher at the Scientific and Polyclinic Department, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, mejevitinova@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2977-9065

Elmira R. Dovletkhanova, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Scientific and Polyclinic Department, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, eldoc@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2835-6685

Maria A. Kepsha, Junior Researcher, doctor at the Scientific and Polyclinic Department, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, m_kepsha@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4201-1360

Vladimir E. Frankevich, Dr. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Deputy Director of the Institute of Translational Medicine, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997; Siberian State Medical University, Ministry of Health of Russia,

v_frankevich@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9780-4579

Vera N. Prilepskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Honored Scientist of the Russian Federation, Head of the Scientific and Polyclinic Department, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, v_prilepskaya@oparina4.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3993-7629

Gennady T. Sukhikh, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Academician of the RAS, Director, V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, 4, Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, sekretariat@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7712-1260