Comparison of the course and outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hypertensive disorders

Objective: To compare the course of pregnancy, childbirth, and pregnancy outcomes in patients with hypertensive disorders.Shelekhin A.P., Baev O.R., Krasnyi A.M.

Materials and methods: A retrospective study enrolled 335 pregnant women, who were divided into 6 groups. Group 1 included uncomplicated pregnancies (control group, n=60), Group 2 included patients with gestational arterial hypertension (GAH, n=55), Group 3 included patients with chronic arterial hypertension (CAH, n=60), Group 4 included patients with moderate preeclampsia (MPE, n=60), Group 5 included patients with severe preeclampsia (SPE, n=50), Group 6 included patients with preeclampsia superimposed on chronic arterial hypertension (PE/CAH, n=50).

Results: Pregnant women with hypertensive disorders were older and had a higher body weight than women in the control group. Women with SPE and PE/CAH were more likely to have a history of PE. The highest rate of edema was observed in the MPE group. Compared to the GAH and CAH groups, uterine-placental and fetal–placental blood flow disorders were significantly more often diagnosed in patients with PE. Pregnancies with SPE were more often complicated by fetal growth restriction and HELLP syndrome. The highest preterm birth was observed in the SPE (52%) and PE/CAH (44%) groups. Most low-birthweight deliveries and neonatal complications occurred in the SPE and PE/CAH groups.

Conclusion: The most adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes were observed in the early-onset hypertensive disorders, especially in patients with SPE and PE/CAH. Particular attention should be paid to women with CAH, who constitute the basis of the PE/CAH group and have a high rate of operative delivery.

Authors' contributions: Shelekhin A.P. – data collection and analysis, literature review, manuscript drafting; Baev O.R. – data collection and analysis, manuscript critical revision and editing, manuscript drafting; Krasnyi A.M. – manuscript editing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Shelekhin A.P., Baev O.R., Krasnyi A.M. Comparison of the course and outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hypertensive disorders.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; 1: 41-47 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.248

Keywords

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a major health problem and the leading cause of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity. They represent a spectrum of diseases including gestational arterial hypertension (GAH), chronic arterial hypertension (CAH), preeclampsia (PE), and preeclampsia with superimposed chronic arterial hypertension (PE/CAH) [1, 2]. PE is considered to be the most severe hypertensive complication of pregnancy, and it often develops superimposed on another previous hypertensive condition [3]. Severe PE, in addition to the symptoms of hypertension and proteinuria, which are diagnostic criteria, is associated with end-organ dysfunction, including neurological disorders, liver and renal failure, significantly worsening the prognosis [4]. PE is classified by severity into moderate and severe forms, and by time of manifestation into early-onset (before week 34) and late-onset (after week 34) PE [5]. Despite the plethora of research, PE remains a mystery, the cause of which still remains not fully understood [6].

To a large extent, pregnancy outcomes and long-term consequences for mother and child depend on the severity of the pregnancy complication [7]. As hypertensive disorders increase the risk of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, a timely and accurate diagnosis and the right choice of a treatment strategy for such patients are important to prevent severe complications [8]. One of the difficult tasks of managing patients with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy is their differential diagnosis [9].

The study of hypertensive disorders, their distinctive features, and course can provide a clearer picture to assess severity, help to predict outcomes, and choose the most appropriate management strategy for pregnancy and delivery. However, with a relatively large number of studies devoted to individual forms of hypertensive disorders, there are not enough studies comparing them with each other.

This study aimed to compare the course of pregnancy, childbirth, and pregnancy outcomes in patients with hypertensive disorders of different severity.

Materials and methods

A retrospective, comparative study was conducted at the Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. The study included 335 pregnant women managed from 2019 to 2022 who were divided into 6 groups. Group 1 included uncomplicated pregnancies (control group, n=60), Group 2 included patients with gestational arterial hypertension (GAH, n=55), Group 3 included patients with chronic arterial hypertension (CAH, n=60), Group 4 included patients with moderate preeclampsia (MPE, n=60), Group 5 included patients with severe preeclampsia (SPE, n=50), Group 6 included patients with preeclampsia superimposed on chronic arterial hypertension (PE/CAH, n=50). Comparison of neonatal outcomes was performed separately for preterm and full-term infants. The study inclusion criteria were age 18–45 years; singleton pregnancy; hypertensive disorders that complicate pregnancy (for groups 2–6). Exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancies; cancer; autoimmune diseases; organ transplants; congenital fetal malformations; acute phase and exacerbation of chronic infectious diseases.

The diagnostic criteria used were in accordance with the Clinical Guidelines "Preeclampsia. Eclampsia. Edema, proteinuria, and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period" [10].

Baseline evaluation included patient history, general and obstetric and gynecological examination, clinical and biochemical blood tests (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, markers of PE), urinalysis with proteinuria determination, ultrasound examination, ultrasound, Doppler ultrasound, and cardiotocography.

Statistical analysis

The results of the study were entered into the MS Excel database. Statistical analysis was performed using Stattech software (Russia). The normality of the distribution was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk or Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Quantitative variables that showed normal distribution were expressed as means (M) and standard deviation (SD) and presented as M (SD); otherwise, the median (Me) with the interquartile range (Q1; Q3) was reported. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the numerical data between three or more groups followed by the Dunn multiple comparison test with Holm correction. Frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. The percentages were compared using Pearson's chi-square test (χ2) using contingency tables. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

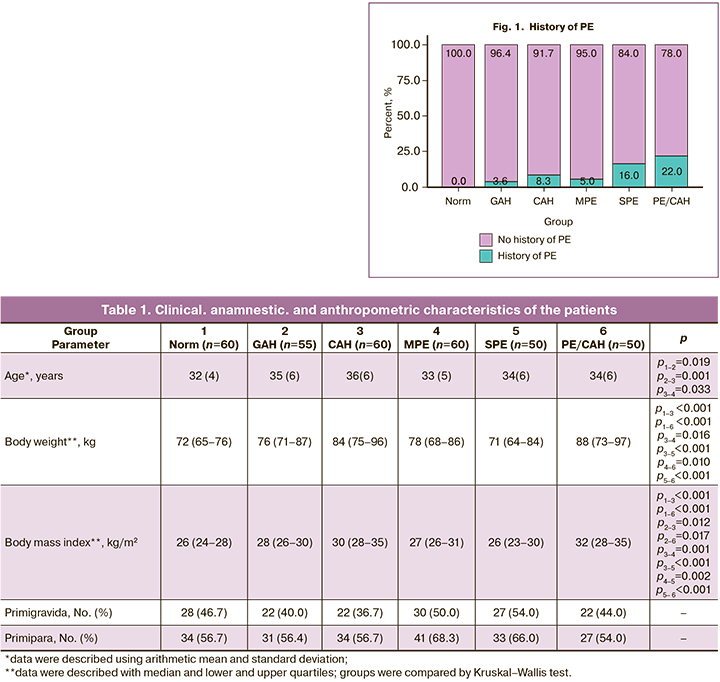

The mean age of pregnant women with hypertensive disorders was higher than that of the uncomplicated pregnancy group. Pregnant women with CAH and PE/CAH had the highest body weight and BMI (Table 1).

The number of primigravida and primipara women did not differ in all groups. A history of PE was more common in the PE/CAH (11/50) and SPE ((8/50) groups, p<0.04–0.001) (Fig. 1).

There were no significant differences in the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus, oligohydramnios, pregnancy anemia, isthmic cervical insufficiency, retrochorial hematoma, and threatened termination of pregnancy in early pregnancy (Table 2).

Edema was most frequently detected in the MPE group [35/60 (63.6%)], which was greater than in the SPE [27/50 (55.1%)) and PE/CAH groups (23/50 (46%)]. Edema was the least common in the control group [3/60 (5%)] and in the CAH group [18/60 (30%)].

Early-onset PE (before 34 weeks) was diagnosed in 15/60 patients with MPE (25%), 12/50 with PE/CAH (24%), and 22/50 with SPE (44%) (p=0.035). Impaired uterine-placental blood flow and fetoplacental blood flow were most common in women with PE. The highest rate (70% impaired uterine-placental blood flow and 22% impaired fetoplacental blood flow) was in patients with PE/CAH. Impaired uterine-placental blood flow was diagnosed by Doppler ultrasound in 53.1% of patients with early-onset PE and in 12.6% with late-onset PE (p<0.001).

Fetal growth restriction was also most frequently detected in women with PE. This complication was noted in every third woman with SPE, every fifth woman with MPE, and PE/CAH.

HELLP syndrome was observed only in the SPE and PE/CAH groups. HELLP syndrome occurred more frequently in early-onset [8/12 (66.7%)) than in late-onset PE (4/12 (33.3%)], p=0,009.

The highest ratios of angiogenesis markers (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, and placental growth factor (sFlt-1/PIGF) were found in patients with MPE, SPE PE/CAH [184 (198), 363 (439) and 214 (189)], respectively. The ratio of these markers in the GAH [51 (69)] and CAH [38 (44)] groups was lower than in PE (p<0.001), but significantly exceeded the reference range for uncomplicated pregnancy.

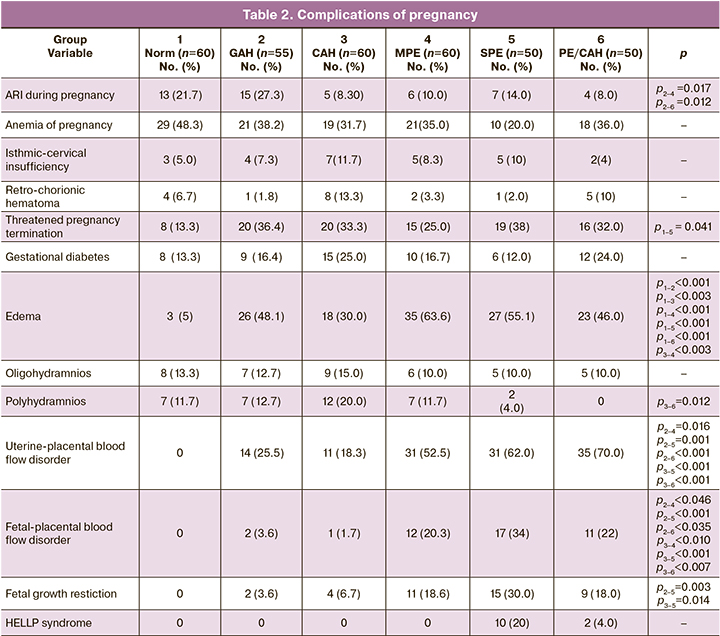

The severe PE and PE/CAH groups had the lowest gestational age at delivery, indicating the severity of these conditions (Fig. 2).

Early delivery in pregnant women with hypertensive disorders is necessary due to deterioration of the fetus condition. Only 2/50 women (4%) in the SPE group and 1/50 women (2%) in the PE/CAH group gave birth at 22 to 27.6 weeks. At 28–31.6 weeks gave birth 9/50 (18%) patients with SPE, 5/50 (10%) with PE/CAH, and 4/60 (6.7%) with MPE. Delivery at 32–33.6 weeks' gestation occurred with equal frequency in the SPE and PE/CAH groups (16% each), in 6.7% in MPE group, and less frequently in the GAH and CAH groups (1.8 and 1.7%, respectively).

Patients with PE/CAH and SPE were most likely to give birth at 34–36.6 weeks (14–16%). In the other groups of women with hypertensive disorders, delivery at this gestational age occurred 2–3 times less frequently. In the control group, all participants gave birth at full-term at 37–41.6 weeks. There were significant differences between the GAH and SPE (p<0.001), GAH and PE/CAH (p=0.009), CAH and SPE (p<0.001), CAH and PE/CAH (p=0.002) groups.

In the control group, induction of labor was performed in 18/60 women at full term (37–41 weeks) for the following indications: anatomical narrow pelvis, prematurity, large fetus, and polyhydramnios (Fig. 3). In the remaining women, the main indication for induction of labor was the need to complete the pregnancy due to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Induction of labor was used most frequently in patients with MPE (40%) and less frequently in SPE (8%).

Induction of labor in the GAH, CAH and MPE groups was performed at 37–40 weeks of gestation; in the SPE group, it was performed before 39 weeks of gestation.

The elective cesarean delivery rate was highest in the SPE (84%), CAH (75%) and PE/CAH group (62%), which was significantly higher than in the MPE group (p<0.001, p<0.004, p<0.052). The main indications included negative changes in blood flow in the fetal-maternal system according to Doppler ultrasound, an increase in severity of PE (increased edema, unstable hemodynamic parameters despite antihypertensive therapy), and worsening fetal condition according to cardiotocography.

When comparing the groups of pregnant women with hypertensive disorders, fewer cesarean sections were performed in women undergoing labor induction. Of the 56 women who had induced labor, only 7 underwent cesarean section (12.5%).

Antihypertensive and magnesia therapy were used to treat hypertensive disorders. In the group of pregnant women with GAH, 78.2% of the women received alpha-adrenomimetics (dopegyt), 50.9% received therapy with calcium channel blockers (nifedipine), and 5/55 (9.1%) patients received magnesia therapy. 83.3% of women with CAH received dopegyt, 76.7% received nifedipine, 8/60 (13.3%) patients received beta-blockers (bisoprolol) and 15/60 (25%) received magnesia therapy. It should be noted that women in the GAH and CAH groups received magnesia therapy only at the time of hospitalization for high BP, when it was not possible to confidently exclude PE without additional examination. There were no differences between the MPE and CAH groups in terms of the medications administered. Magnesia therapy was more frequently prescribed in the SPE group (36/50 (72%)) and beta-blockers (11/50 (22%)) in the PE/CAH group.

When comparing neonatal outcomes, we divided newborns into full-term and preterm neonates. For preterm birth, the birth weight of the newborns did not differ significantly. In preterm birth, the lowest birth weight was found in the SPE group (1488 (573)).

Assessment of the course of the neonatal period showed that, compared with newborns born to healthy mothers, preterm newborns from mothers with hypertensive disorders had a 2-fold higher incidence of hyperbilirubinemia (6.4–8.3%), anemia (3.6–8.9%), and intraventricular hemorrhage (3.6–8.3%). In one case in a patient with SPE, a preterm newborn developed a clinic of necrotizing enterocolitis. These complications were common in all patients with PE. The cumulative incidence of neonatal complications in the MPE, SPE, and PE/CAH groups was statistically significantly higher than in the control group (p<0.03; p<0.04; p<0.03), but did not differ significantly from that in the GAH and CAH groups.

In preterm infants, complications were even more frequent: hyperbilirubinemia in 30.8–59.1%, p<0.001, anemia in 40–75%, p<0.001, intraventricular hemorrhage in 32–38.5%, p<0.001, necrotizing enterocolitis in 12–18.2%, p<0.01, pneumonia in 25–68.2% and respiratory distress syndrome in 7.7–50%. Early neonatal death occurred in 4 preterm infants: 1 in the CAH group 2 in the SPE group, and 1 in the PE/CAH group. The cumulative incidence of neonatal complications in the SPE and PE/CAH groups was significantly higher than in the GAH group, but did not differ from that of the CAH and MPE groups.

Neonatal death was recorded of 2 cases in SPE after cesarean section at weeks 26 and 27 and in 1 case in the PE superimposed on CAH after an emergency cesarean section at 28 weeks of pregnancy due to deterioration or fetal condition. In all cases, there was an early manifestation of PE and fetal growth restriction.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the course of pregnancy, delivery mode, maternal, and perinatal outcomes in patients with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy.

Clinical and medical history analysis showed that pregnant women with CAH were older than those in the other groups and had the highest body weight. A history of PE was more common in women in the SPE and PE/CAH groups.

The sFlt-1/PIGF ratio was highest in the SPE group and lowest in the CAH group, which confirms the results obtained in earlier studies.

Abnormalities in uteroplacental and fetal placental blood flow were more frequent in the SPE and PE/CAH groups, as well as in the early manifestation of these conditions. Fetal growth restriction was the most common in patients with SPE. HELLP syndrome was also more frequent in SPE than in the other groups.

The surgical delivery rate was highest among patients with CAH, SPE, and PE/CAH, probably due to the need to deliver these patients as soon as possible.

The use of labor induction was associated with a decrease in the number of cesarean sections, which is consistent with earlier studies [11]. More favorable outcomes in pregnant women with hypertensive disorders during induction of labor appear to be due to the initially less severe course of the complication. However, this also indicates that vaginal delivery is a gentler method for these women, as it excludes surgical stress and increased blood loss. In this sense, early diagnosis and timely assessment of the severity of hypertensive disorders allow the most appropriate management strategy for patients with hypertensive disorders and determines the optimal timing and delivery mode. A study by Hagans M.J. et al. (2022) [12] confirms that labor induction is associated with higher chances of natural delivery.

The highest number of neonatal complications, such as hyperbilirubinemia, necrotizing enterocolitis, neonatal pneumonia, and respiratory distress syndrome, was observed among patients with SPE and PE/CAH, which confirms the data of other studies comparing hypertensive disorders during pregnancy [13]. However, the severity of neonatal complications is also due to early gestational age at delivery.

The findings suggest that SPE, PE/CAH, and early manifestations of these conditions most often lead to serious complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes, as well as adversely affect neonates. Furthermore, patients with SPE and PE/CAH had a high preterm delivery rate, which is reflected in neonatal outcomes. At the same time, women with CAH also deserve special attention, as they are the basis for the PE/CAH group and have a high rate of operative delivery. Improving the management of women in this group represents a reserve for reducing the rate of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with hypertensive disorders.

Conclusion

The uncertainty of the course of hypertensive disorders, their possible progression to more severe complications and life-threatening condition determine the importance of surveillance and vigilance towards these patients. The study findings show that SPE, PE/CAH, and early manifestations of these conditions most often lead to serious complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes for the mother and fetus. Improving the management of women with CAH represents a reserve for reducing the incidence of adverse outcomes.

References

- Sutton A.L.M., Harper L.M., Tita A.T.N. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2018; 45(2): 333-47. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2018.01.012.

- Chahine K., Sibai B. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy: new concepts for classification and management. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019; 36(2): 161-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1666976.

- Hauspurg A., Countouris M.E., Catov J.M. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and future maternal health: how can the evidence guide postpartum management? Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2019; 21(12): 96. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/S11906-019-0999-7.

- Guedes-Martins L. Superimposed preeclampsia. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017; 956: 409-17. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/5584_2016_82.

- Büyükeren M., Çelik H.T., Örgül G., Yiğit Ş., Beksaç M.S., Yurdakök M. Neonatal outcomes of early- and late-onset preeclampsia. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2020; 62(5): 812. https://dx.doi.org/10.24953/turkjped.2020.05.013.

- Brown M.A., Magee L.A., Kenny L.C., Karumanchi S.A., McCarthy F.P., Saito S. et al. The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018; 13: 291-310. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2018.05.004.

- Bokslag A., van Weissenbruch M., Mol B.W., de Groot C.J.M. Preeclampsia: short and long-term consequences for mother and neonate. Early Hum. Dev. 2016; 102: 47-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.EARLHUMDEV.2016.09.007.

- Shen M., Smith G.N., Rodger M., White R.R., Walker M.C., Wen S.W. Comparison of risk factors and outcomes of gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia. PloS One. 2017; 12(4): e0175914. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0175914.

- Agrawal A., Wenger N.K. Hypertension during pregnancy. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2020; 22(9): 64. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/S11906-020-01070-0.

- Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Преэклампсия. Эклампсия. Отеки, протеинурия и гипертензивные расстройства во время беременности, в родах и послеродовом периоде. Клинические рекомендации. 2021. [Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Preeclampsia. Eclampsia. Edema, proteinuria and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. Clinical guidelines. 2021. (in Russian)].

- Хлестова Г.В., Карапетян А.О., Шакая М.Н., Романов А.Ю., Баев О.Р. Материнские и перинатальные исходы при ранней и поздней преэклампсии. Акушерство и гинекология. 2017; 6: 41-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.6.41-7. [Khlestova G.V., Karapetyan A.O., Shakaya M.N., Romanov A.Yu., Baev O.R. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in early and late preeclampsia. Akusherstvo i ginekologiia/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017; 6: 41-7. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2017.6.41-7.

- Hagans M.J., Stanhope K.K., Boulet S.L., Jamieson D.J., Platner M.H. Delivery outcomes after induction of labor among women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022; 35(25): 9215-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2021.2022645.

- Муминова К.Т., Ходжаева З.С., Шмаков Р.Г. Особенности течения беременности у пациенток с гипертензивными расстройствами. ДокторРу. 2019; 166(11): 14-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.31550/1727-2378-2019-166-11-14-21. [Muminova K.T., Khodzhaeva Z.S., Shmakov R.G. Specifics of Pregnancy in Patients with Hypertensive Disorders. DoctorRu. 2019; 166(11): 14-21. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.31550/1727-2378-2019-166-11-14-21.

Received 18.10.2022

Accepted 28.12.2022

About the Authors

Artemiy P. Shelekhin, Postgraduate Student, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University), dr.shelekhin@gmail.com,https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7682-1329, 2. Trubetskaya str., Moscow, 119991, Russia.

Oleg R. Baev, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the 1st Maternity Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia;

Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatology and Reproductology, I.M. Sechenov First MSMU, Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University),

o_baev@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8572-1971, 4 Ac. Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia.

Alexey M. Krasnyi, PhD, Head of the Cytology Laboratory, Academician V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, a_krasnyi@oparina4.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7883-2702, 4. Ac. Oparina str., Moscow, 117997, Russia.