The role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of infertility in patients with familial Mediterranean fever

Objective: To investigate the prevalence of infertility-related laparoscopic findings among patients with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), female genital tuberculosis (FGTB), and those without FMF or FGTB. Materials and methods: This cross-sectional study included 204 patients with infertility. The patients were divided into a group of 50 women with FMF, median age 29 (26; 31.8) years, a comparison group of 44 women with FGTB, median age 29 (25; 33) years, and a control group of 110 patients without FMF or FGTB, median age 32 (28; 36) years. Results: Compared with control subjects, patients with FMF and FGTB had higher incidence of pelvic adhesions (RR=2.83 [95% CI: 1.97; 4.07]; p<0.001 and 3.3 [95% CI: 2.34; 4.66]; p<0.001, respectively), free fluid (RR=3.3 [95% CI: 1.93; 5.65]; p<0.001 and 3.12 [95% CI: 1.79; 5.45]; p<0.001, respectively), and peritoneal lesions (p<0.001). Conversely, they were less likely to have genital endometriosis (RR=0.46 [95% CI: 0.27; 0.78]), p=0.002 and 0.22 [95% CI: 0.09, 0.51]; p<0.001, respectively). Tubal occlusion was more common in patients with FGTB than in controls and patients with FMF (RR=5.63 [95% CI: 3.5; 9.04]; p<0.001 and 2.41 [95% CI: 1.6; 3.63]; p<0.001, respectively). In the FMF group tubal occlusion was more common than in the control group (RR=2.34 [95% CI: 1.29; 4.24], p=0.009). Tubal peritoneal infertility was predominantly diagnosed in patients with FMF (RR=2.59 [95% CI: 1.99; 3.38]; p<0.001 and FGTB (RR=2.76 [95% CI: 2.13; 3.56]; p<0.001). Repeated pelvic surgery was more common in FMF patients than in patients with FGTB (p<0.001) and in controls (p<0.001); in the FGTB group it was observed more often than among controls (p=0.006) Patients with FMF and FGTB were more likely to undergo coagulation/cauterization of polycystic ovaries (p=0.009 and <0.001, respectively) and ovarian resection (p<0.001). Conclusion: FMF and FGTB are associated with an increased risk of pelvic adhesion, tubal occlusion, free fluid, peritoneal lesions, and tubal peritoneal infertility. Both conditions often require repeated pelvic surgery such as coagulation/cauterization of polycystic ovaries and ovarian resection. Authors' contributions: Sotskiy P.O. – conception and design of the study, statistical analysis, manuscript drafting; Sotskiy P.O., Sotskaya O.L. – data collection and analysis; Sotskaya O.L., Safaryan M.D., Mkhitaryan A.G., Hayrapetyan H.S. – manuscript editing. Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Funding: There was no funding for this study. Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Center for Medical Genetics and Primary Health Care. Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data. Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator. For citation: Sotskiy P.O., Sotskaya O.L., Safaryan M.D., Mkhitaryan A.G., Hayrapetyan H.S. The role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of infertility in patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (8): 86-94 (in Russian) https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.47Sotskiy P.O., Sotskaya O.L., Safaryan M.D., Mkhitaryan A.G., Hayrapetyan H.S.

Keywords

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is a hereditary, ethnically determined autoinflammatory disease characterized by periodic fever and serositis [1–7]. The discovery of the MEFV gene in 1997 by two independent consortia significantly advanced the understanding of the molecular and genetic underpinnings of FMF [1]. Situated on the short arm of chromosome 16 (16p 13.3), the MEFV gene comprises 10 exons, with FMF-associated missense mutations identified in exons 2, 3, 5, and 10. Most common mutations include M694V, M680I, V726A, and M694I in exon 10 and E148Q in exon 2. Recurrent peritonitis episodes can potentially lead to the development of abdominal adhesions and fibrosis, resulting in intestinal obstruction, fallopian tube blockage, and hindered ovulation [1, 7–9]. The accumulation of Serum Amyloid A 1 (SAA1) primarily occurs in the liver, kidneys, and intestines, with potential impacts on the genitourinary system as well [1, 10, 11]. Despite limited research on the reproductive system of patients with FMF, a handful of studies have explored this connection [1, 4–9, 12]. Among the imaging modalities for infertility assessment, laparoscopy is the most commonly used [13–17]. Authors have reported varying sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing uterine and fallopian tube pathologies using laparoscopy [13, 14]. However, the relationship between FMF and infertility remains inadequately understood, with no existing literature investigating the role of laparoscopy in diagnosing infertility, specifically among FMF patients. Thus, our study aimed to address this knowledge gap in a patient cohort exhibiting a notably high FMF prevalence.

This study aimed to explore and compare the prevalence of laparoscopic findings related to infertility among three distinct groups: patients with FMF, individuals with female genital tuberculosis (FGTB), and subjects without FMF or FGTB.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study included 204 infertile patients. The patients were divided into a study group of 50 women with FMF, median age 29 (26; 31.8) years; a comparison group of 44 women with FGTB, median age 29 (25; 33) years; and a control group of 110 patients without FMF or FGTB, median age 32 (28; 36) years.

The baseline clinical evaluation of patients included a complete clinical examination with the completion of a widely accepted, specially designed questionnaire, which included symptoms of the disease (fever, peritonitis, pleurisy, arthritis, arthralgia, skin rashes in the form of pseudo-erysipeloid rash, proteinuria, renal amyloidosis, etc.), demographic parameters (sex, age, ethnic origin), and family cases.

The Tel-Hashomer criteria as a method for the clinical diagnosis of FMF. The diagnosis of FMF was confirmed using the international Tel-Hashomer criteria and molecular genetic analysis of the 12 most common MEFV mutations in the Armenian population [18].

Molecular genetic methods for diagnosing FMF. Molecular genetic studies were performed under the supervision of the Head of the Laboratory of Genetics of Autoinflammatory Diseases of the Center for Medical Genetics, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Prof. A.S. Hayrapetyan. Peripheral whole blood served as material for determining mutations in the MEFV and SAA1 genes. Whole venous blood was drawn into EDTA contained tubes to prevent blood clotting and DNA degradation. For DNA isolation, special MOBIO laboratory kits (UltraCleanBlood DNA Isolation Kit; USA) were used. Mutations were determined by multiplex amplification of the DNA region containing the gene under study, reverse hybridization of the resulting amplicons, control in a parallel study, and visualization of mutations using an enzymatic reaction (ViennaLab FMF&SAA1 Assay).

Hybridization of amplification products with a test strip containing allele-specific oligonucleotide probes was performed as a parallel-line test. The analysis included the following 12 MEFV mutations: E148Q, P369S, F479L, M680I (G/C), M680I (G/A), I692del, M694V, M694I, K695R, V726A, A744S, and R761H.

Gynecological examinations included general and obstetric and gynecological history data, characteristics of complaints, and characteristics of menstrual and reproductive function. All the patients underwent bimanual pelvic examination, general clinical examination, and abdominal and pelvic ultrasonography.

Laparoscopy with chromosalpingoscopy was performed according to the standard techniques.

Other methods of examination. To detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the National Reference Laboratory for Diagnosis of Tuberculosis, the following studies were performed: smear staining according to Ziehl–Neelsen and fluorescence microscopy, inoculation on Loevenshtein-Jensen medium or BACTEC 460, or mycobacteria growth inhibitor tube (MGIT). The object of the study was surgical material, including tissue samples of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, peritoneum, omentum, and adhesions. The pathomorphological study was carried out at the Armenian-German Scientific and Practical Center for Pathology “Histogen” under the guidance of Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor, Pathologist, Head of the Laboratory of the “Armenian-American Health Center Foundation” A.G. Mkhitaryan according to generally accepted criteria [19–21]. If amyloidosis was suspected, a histological examination of tissue samples from the ovaries, fallopian tubes, peritoneum, omentum, parenchymal organs, and adhesions was used [10, 11]. Staining was carried out with Congo red, and the preparations were evaluated by light and polarization microscopy. Under the morphological signs of chronic nonspecific productive inflammation of the fallopian tubes, we understood that diffuse or perivascular lympho-plasmocellular infiltration extending to the outer sections of the wall of the fallopian tube or in combination with inflammation in the stroma of the endosalping folds, uneven distribution of fibers in the muscular layer of the tube, diffuse or large-focal lymphoplasmic cell infiltration in the serous layer of the tube and fibro-adipose tissue of the mesosalpinx, shortening and thickening of the folds of the fimbrial sections of the tube, fibrosis, sclerosis of their stroma, signs of chronic perisalpingitis with changes in all layers of the wall or in combination with chronic inflammation in the serous layer of the tube, or in an isolated form. The histopathological sign of tuberculous inflammation was consistent with the detection of epithelioid granulomas [22–24].

The inclusion criteria were data from a comprehensive examination of the reproductive system, laparoscopy, reproductive period, and consent to participate in the study. Confirmation of the diagnosis of FMF using international Tel-Hashomer criteria and molecular genetic testing, and verification of the diagnosis of FGTB by pathomorphological and/or cultural methods. Exclusion criteria were malignant neoplasms, cardiovascular diseases, and autoimmune diseases.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and visualization were performed using R 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages (n (%)) for continuous variables as median (Me) with interquartile range (Q1; Q3). Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare numerical data between three or more groups, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test with Holm's correction. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test with the Yates correction as a post hoc method for pairwise comparisons, and the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used (when the expected frequencies in the cell of the contingency table was less than 5 in at least one of the cells). The Hill procedure was used to control inflation at the rate of type I errors. The relative risk (RR) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used to assess the strength of the association. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

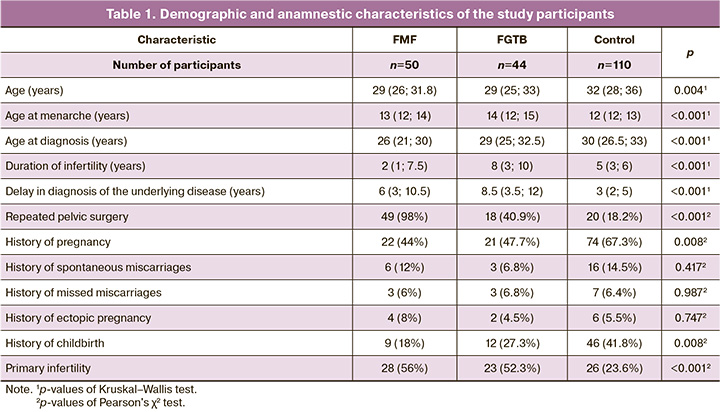

This study included 204 infertile patients. Table 1 presents comparative demographic and anamnestic characteristics of the study participants. In patients with infertility associated with FMF and FGTB, the median reproductive ages were comparable: 29 years (26; 31.8) and 29 years (25; 33) (p=0.097), respectively. The patients in the control group were older, 32 years (28; 36). The median age at menarche in the control group was 12 years (12; 13), which was significantly lower than the median age at menarche in patients with FMF, 13 years (12; 14) (p=0.006) and FGTB, 14 years (12; 15) (p<0.001). Patients in the FMF and FGTB groups were less likely to have a history of pregnancy in 22/50 (44.0%) and 21/44 (47.7%) patients, respectively, compared with 74/110 (67.3%) in the control group (p=0.027 and 0.077, respectively). A history of childbirth was reported by 9/50 (18%) women in the FMF group, which was significantly lower than that among controls, 46/110 (41.8%), (p=0.017). There were no differences between the groups in terms of the spontaneous miscarriage rate (p=0.417), missed miscarriage rate (p=0.987), or ectopic pregnancies (p=0.747). Primary infertility among patients with FMF, 28/50 (56.0%) and FGTB, 23/44 (52.3%) was significantly more common than in controls – in 26/110 (23.6%) (p<0.001 and 0.002, respectively). Patients with FGTB were characterized by a longer duration of infertility, 8 years (3; 10), compared with patients with FMF, 2 years (1; 7.5) (p<0.001), and in the control group, 5 years (3; 6) (p=0.014). A comparative analysis revealed a significantly shorter duration of infertility in patients with FMF than in the control group (p=0.028). The median age at diagnosis among patients with FMF was the lowest, 26 years (21; 30) compared with FGTB, 29 years (25; 32.5), (p=0.027) and controls, 30 years (26.5; 33), (p<0.001). Prior to laparoscopy, women were under medical observation in the general medical network, family planning, and reproduction centers for infertility as well as in the Center for Medical Genetics for FMF. The age at FMF manifestation was < 20 years in 35/50 (70.0%) women and < 20 years in 15/50 (30.0%) women. The age at FGTB manifestation coincided with the onset of sexual activity in 31/44 (70.5%), 10/44 (22.7%) with spontaneous abortion or after childbirth, and 4/44 (9.1%) with age at menarche, whereas in the control group, the majority with the onset of sexual activity. The median duration of the delay in the diagnosis of FMF and FGTB was 6 (3; 10.5) and 8.5 (3.5; 12) years, respectively, which differed from the duration of the delay in the diagnosis of the underlying disease in the control group, 3 years (2; 5) (p<0.001). An increased frequency of repeated pelvic surgeries was found in the FMF group, in 49/50 (98.0%), in the FGTB group, in 18/44 (40.9%), which was significantly higher than that in the FGTB group (p<0.001) and control group (p<0.001); it was also higher in the FGTB group than in the control group (p=0.006).

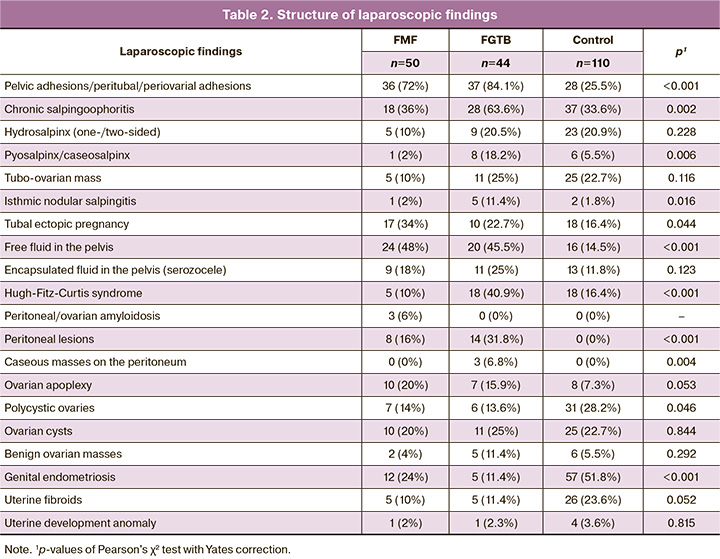

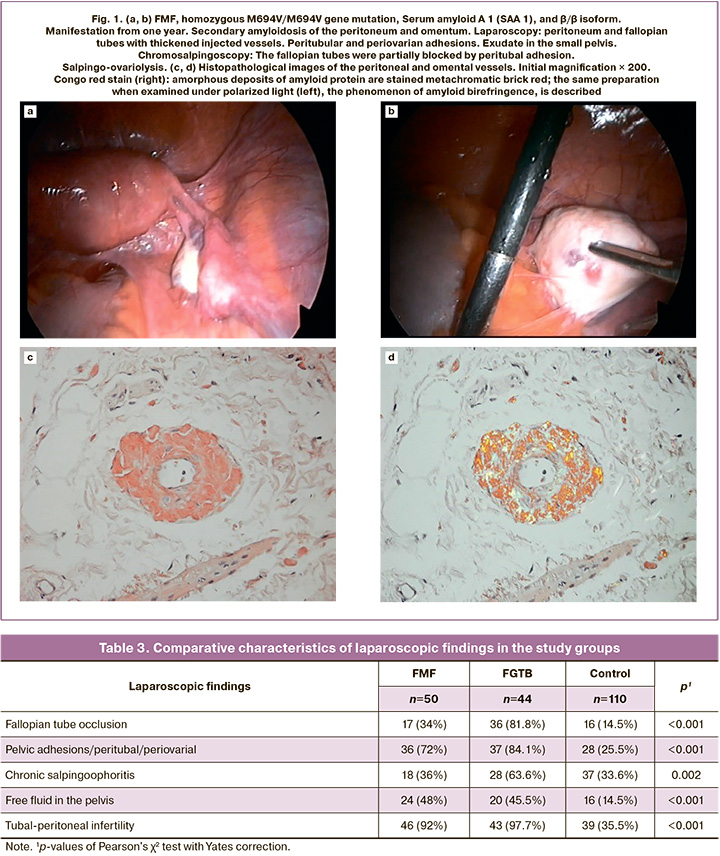

Table 2 presents the frequency of laparoscopic findings in the study groups. Comparative analysis showed that patients with FMF and FGTB had a statistically significantly higher incidence of pelvic adhesions and peri-tubal and periovarian adhesions (relative risk (RR)=2.83 [95% CI:1.97; 4 .07], p<0.001 and 3.3 [95% CI:2.34; 4.66], p<0.001, respectively), free pelvic fluid (RR=3.3 [95% CI:1, 93; 5.65], p<0.001 and 3.12 [95% CI:1.79; 5.45], p<0.001, respectively), peritoneal lesions (p<0.001), and a statistically significantly lower incidence of genital endometriosis (RR=0.46 [95% CI:0.27; 0.78], p=0.002 and 0.22 [95% CI:0.09; 0.51], p<0.001, respectively). In addition, the incidence of tubal ectopic pregnancy was slightly higher in the FMF group than in the control group (p=0.065). Compared with patients in the control group and FMF, patients with FGTB had a higher incidence of chronic salpingo-oophoritis (RR=1.89 [95% CI:1.34; 2.67], p=0.004 and 1.77 [95% CI:1.15; 2.72], p=0.027, respectively), pio- or caseosalpinx (RR=3.33 [95% CI:1.23; 9.05], p=0.05, and 9.09 [ 95% CI:1.18; 70], p=0.034, respectively), and Hugh–Fitz–Curtis syndrome (RR=2.5 [95% CI:1.44; 4.34], p=0.005 and 4, 09 [95% CI:1.66, 10.1], p=0.004, respectively). In addition, there was a tendency for a higher incidence of isthmic nodular salpingitis in this group of patients than in the control group (p=0.066).

Diagnostic laparoscopy findings (Table 3) showed that tubal occlusion was more often found in patients with FGTB than in the control group and patients with FMF (RR = 5.63 [95% CI:3.5; 9, 04], p<0.001 and 2.41 [95% CI:1.6; 3.63], p<0.001, respectively), and in patients with FMF than in controls (RR=2.34 [95% CI:1.29, 4.24], p=0.009). Pelvic free fluid and tuboperitoneal infertility were more frequently diagnosed in the FMF groups (RR=3.3 [95% CI:1.93; 5.65], p<0.001 and 2.59 [95% CI:1 .99; 3.38], p<0.001, respectively) and FGTB (RR=3.12 [95% CI:1.79; 5.45], p<0.001 and 2.76 [95% CI:2, 13; 3.56], p<0.001, respectively), compared with the control group.

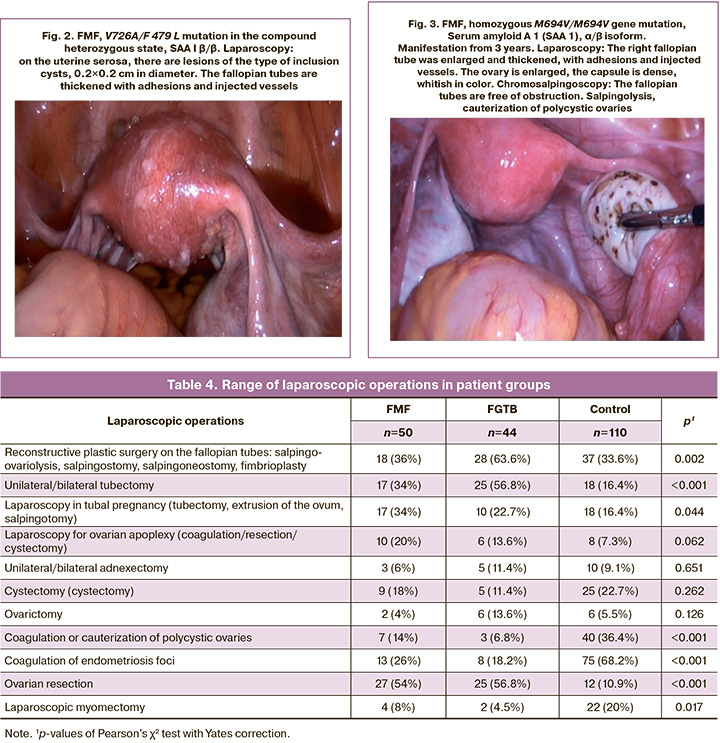

Amyloidosis of the ovaries and peritoneum was found in of 3/50 (6.0%) women (Fig. 1a). In the walls of the vessels of the fallopian tubes, omentum, and peritoneum, pronounced thickening associated with the accumulation of amorphous amyloid masses was observed (Fig. 1b, d). In 5/50 (10.0%) patients, changes were found in the serous membrane of the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and between the intestinal loops in the form of cyst-like transparent eruptions measuring 0.5 to 0.9 cm in diameter and containing serous fluid (Fig. 2). We compared the laparoscopic picture with the pathomorphological picture obtained by biopsy of the uterine wall, fallopian tube, ovary, and the serous cover of the intestine. Miliary uterine lesions microscopically corresponded to granulomas with mesothelial hyperplasia and focal invaginations of the mesothelium into the serous layer, with the formation of inclusion cysts.

Table 4 presents the range of laparoscopic surgical interventions performed in this study. Reconstructive plastic surgery on the fallopian tubes was significantly more often performed in patients with FGTB than in the control and FMF groups (p=0.004 and 0.027, respectively). Unilateral or bilateral tubectomy was performed significantly more frequently in patients with FGTB than in controls and patients with FMF (p<0.001 and 0.044, respectively). At the same time, the frequency of tubectomy in the latter group was also significantly higher than that in the control group (p=0.034). Laparoscopy in tubal pregnancy (tubectomy, extrusion of the ovum, salpingotomy) was performed slightly more often in patients with FMF than in the control group (p=0.065). Compared with the control group, patients with FMF and FGTB were significantly more likely to undergo coagulation or cauterization of polycystic ovaries (p=0.009 and p<0.001, respectively) (Fig. 3) and oophorectomy (p<0.001) and less likely to undergo coagulation of endometriosis foci (p<0.001).

Discussion

Laparoscopy plays a crucial role in diagnosing the causes of infertility in married couples [13–17, 22–24]. From an evidence-based medicine perspective, laparoscopy is considered the "gold standard" for diagnosing tubal peritoneal infertility (sensitivity, 95.7%; specificity, 100%) (IA) and endometriosis-associated infertility (IA) [13]. A common shortcoming of many studies is the explicit or implicit assumption that laparoscopy is the definitive method for investigating infertility, which is inaccurate [13]. In gynecological practice, diagnosing FMF can be challenging without awareness of the existence of the disease. Patients often undergo extensive examinations; however, the diagnosis remains unclear for several years [1, 3–6]. Repeated laparoscopies are used to diagnose tubal-peritoneal infertility and adhesive processes in the small pelvis. Failing to establish a primary diagnosis and treatment typically leads to disease recurrence and ineffective reconstructive plastic surgery. Insufficient utilization of pathomorphological and microbiological methods in studying fallopian tubes and peritoneum in patients with tubal-peritoneal infertility and FGTB contributes to delayed diagnosis and spread of tuberculosis [23, 25, 26]. Amyloidosis was a severe complication of FMF prior to the era of colchicine treatment [10, 11]. This disease can lead to significant ascites, without intestinal obstruction [10]. Identification of amyloidosis requires targeted pathomorphological examination. Other complications include peritoneal adhesions due to recurrent peritonitis resulting in small bowel obstruction, infertility, peritoneal fibrosis, and encapsulating peritonitis. As previously noted by Ehrenfeld E.N. et al., infertility causes in FMF patients include ovulatory dysfunction (46%), peritoneal adhesions (31%), and unexplained (23%) infertility [7]. Zayed A. et al. reported that 24.3% of infertile women with FMF experienced anovulatory cycles. The majority (56.67%) of patients had an accumulation of excessive clear peritoneal fluid in the pelvis due to local inflammation [8]. However, Nabil H. et al. argued that the causes of infertility in patients with FMF do not differ significantly from those expected in the general population [9]. This observation is likely to hold true for patients with FMF undergoing colchicine treatment, which can prevent complications leading to infertility.

Laparoscopy and chromosalpingoscopy are the most reliable diagnostic modalities [22–26]. Despite the apparent similarity between FMF patients and those with FGTB in terms of peritoneal involvement, significant differences exist regarding the extent of damage to the fallopian tubes, ranging from superficial inflammation of the serous membranes in FMF to inflammation of all tube layers with occlusion in FGTB. Encapsulated intercommissural cysts, known as seroceles, are frequently observed in patients with FGTB and FMF, as indicators of peritoneal involvement. Encapsulating peritonitis has been described in the literature under various names, including chronic fibrous encapsulating peritonitis and sclerosing peritonitis [27]. Consequently, our findings are consistent with those of many previous studies. Nevertheless, any remaining discrepancies can be attributed to variations in study group sizes, designs, and treatment protocols.

Conclusion

FMF and FGTB are associated with an increased risk of pelvic adhesion, tubal occlusion, free fluid, peritoneal lesions, and tubal peritoneal infertility. Both conditions often require repeated pelvic surgery, such as coagulation/cauterization of polycystic ovaries and ovarian resection.

References

- Ben-Chetrit E., Levy M. Reproductive system in familial Mediterranean fever: an overview. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003; 62(10): 916-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.62.10.916.

- Özen S., Batu E.D., Demir S. Familial Mediterranean fever: recent developments in pathogenesis and new recommendations for management. Front. Immunol. 2017; 8: 253. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.0025.

- Sönmez H.E., Batu E.D., Özen S. Familial Mediterranean fever: current perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 2016; 9: 13-20. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S91352.

- Atas N., Armagan B., Bodakci E., Kasifoglu T., Satis H., Sari A. et al. Familial Mediterranean fever associated infertility and underlying factors with fertility [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018; 70 (Suppl. 10).

- Ben-Chetrit E. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. UpToDate. May 22, 2018. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-familial-mediterranean-fever/print

- Sarı İ, Birlik M, Kasifoğlu T. Familial Mediterranean fever: an updated review. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 2014; 1(1): 21-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2014.006.

- Ehrenfeld E.N., Polishuk W.Z. Gynecological aspects of recurrent polyserositis (familial Mediterrranean fever, periodic disease). Isr. J. Med. Sci. 1970;6(1):9-13.

- Zayed A., Nabil H., State O., Badawy A. Subfertility in women with familial Mediterranean fever. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2012; 38(10): 1240-4.https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01857.x.

- Nabil H., Zayed A., State O., Badawy A. Pregnancy outcome in women with familial Mediterranean fever. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012; 32(8): 756-9.https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2012.698667.

- Sohar E., Gafni J., Pras M., Heller H. Familial Mediterranean fever: a survey of 470 cases and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. 1967; 43(2): 227-53.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(67)90167-2.

- Huzmeli C., Candan F., Bagci G., Alaygut D., Bagci B., Yildiz E. et al. Evaluation of 61 secondary amyloidosis patients: a single-center experience from turkey. J. Clin. Anal. Med. 2016; 7(5): 695-700. https://dx.doi.org/10.4328/JCAM.448.

- Sotskiy P.O., Sotskaya O.L., Hayrapetyan H.S., Sarkisyan T.F., Yeghiazaryan A.R., Atoyan S.A., Ben-Chetrit E. Infertility causes and pregnancy outcome in patients with Familial Mediterranean fever and controls. J. Rheumatol. 2021;48(4): 608-14. https://dx.doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.200574.

- Радзинский В.Е., ред. Бесплодный брак: версии и контраверсии.2-е изд. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2020. 432с. [Radzinsky V.E., ed. Infertile marriage: versions and counter-versions. 2nd ed. Мoscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2020. 432p. (in Russian)].

- Сухих Г.Т., Назаренко Т.А., ред. Бесплодный брак. Современный подход к диагностике и лечению. Руководство. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2010. 774с. [Sukhikh G.T., Nazarenko T.A., eds. Infertile marriage. A modern approach to diagnosis and treatment: a guide. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2010. 774p. (in Russian)].

- Савельева Г.М., Радзинский В.Е., Манухин И.Б., ред. Гинекология. Национальное руководство. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2017. 1088с. [Savelyeva G.M., Radzinsky V.E., Manukhin I.B., eds. Gynecology. National guide. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2017. 1088с. (in Russian)].

- Краснопольская К.В., Назаренко Т.А. Клинические аспекты лечения бесплодия в браке. Диагностика и терапевтические программы с использованием методов восстановления естественной фертильности и вспомогательных репродуктивных технологий. Руководство. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2013. 376с. [Krasnopolskaya K.V., Nazarenko T.A. Clinical aspects of treatment of infertility in marriage. Diagnosis and therapeutic programs using methods of restoration of natural fertility and assisted reproductive technologies: a guide. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2013. 376p.(in Russian)].

- Фальконе Т., Херд В.В. Репродуктивная медицина и хирургия. Пер. с англ., под ред. Г.Т. Сухих. М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа; 2014. 948с. (in Russian)].

- Livneh A., Langevitz P., Zemer D., Zaks N., Kees S., Lidar T. et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(10): 1879-85. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.1780401023.

- Серов В.Н., Звенигородский И.Н. Диагностика гинекологических заболеваний с курсом патологической анатомии. М.: БИНОМ; Лаборатория знаний; 2003. [Serov V.N., Zvenigorodsky I.N. Diagnosis of gynecological diseases with a course of pathological anatomy. Moscow: BINOM;Knowledge Laboratory; 2003. (in Russian)].

- Хмельницкий О.К. Патология маточных труб. В кн.: Патоморфологическая диагностика гинекологических заболеваний. СПб.: СОТИС; 1994: 286-333. [Khmel'nitskii O.K. Pathology of the fallopian tubes. In: Pathomorphological diagnosis of gynecological diseases. Saint Petersburg: SOTIS; 1994: 286-333. (in Russian)].

- Бродский Г.В., Адамян Л.В., Сухих Г.Т. Маточные трубы при генитальной патологии и интратубарная терапия женского бесплодия. Акушерство и гинекология. 2018; 9: 74-8. [Brodsky G.V., Adamyan L.V., Sukhikh G.T. The fallopian tubes in genital pathology and intratubal therapy for female infertility. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018; (9): 74-8. (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2018.9.74-78.

- Малушко А.В., Кольцова Т.В., Ниаури Д.А. Туберкулез половых органов и спаечная болезнь: факторы риска репродуктивных потерь и женского бесплодия. Проблемы туберкулеза и болезней легких. 2013; 3: 3-9. [Malushko A.V., Kol’tsova T.V., Niauri D.A. Tuberculosis of genital organs and adhesions: risk factors for reproductive losses and female infertility. Problems of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases. 2013; (3): 3-9.(in Russian)].

- Sharma J.B. Current diagnosis and management of female genital tuberculosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India. 2015; 65(6): 362-71. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13224-015-0780-z.

- Sharma J.B., Sneha J., Singh U.B., Kumar S., Roy K.K., Singh N. et al. Comparative study of laparoscopic abdominopelvic and fallopiantube findings before and after antitubercular therapy in female genital tuberculosis with infertility. J. Minim. Invasive Genicol. 2016; 23(2): 215-22.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2015.09.023.

- Grace G.A., Devaleenal D.B., Natrajan M. Genital tuberculosis in females. Indian J. Med. Res. 2017; 145(4): 425-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1550_15.

- Djuwantono T., Permadi W., Septiani L., Faried A., Halim D., Parwati I. Female genital tuberculosis and infertility: serial cases report in Bandung, Indonesia and literature review. BMC Res. Notes. 2017; 10(1): 683.https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-3057-z.

- Dabak R., Uygur-Bayramiçli O., Aydin D.-K., Dolapçioglu C., Gemici C., Erginel T. et al. Encapsulating peritonitis and familial Mediterranean fever. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005; 11(18): 2844-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i18.2844.

Received 20.02.2023

Accepted 11.08.2023

About the Authors

Pavel O. Sotskiy, PhD, obstetrician-gynecologist, Center for Genetics and Primary Health Care, str. Abovyan 34/3, 0001, Yerevan, Armenia, +374 41 188888,pavel.sotskiy@gmail.com

Olga L. Sotskaya, PhD, Associate Professor at the Department of Phthisiology, obstetrician-gynecologist, phthisiogynecologist, Mkhitar Heratsi Yerevan State Medical University, str. Koryun 2, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia; Center for Genetics and Primary Health Care, str. Abovyan 34/3, 0001, Yerevan, Armenia, +374 94 008177, olga.sotskaya@gmail.com

Marina D. Safaryan, Honored Doctor of Armenia, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Phthisiology, Mkhitar Heratsi Yerevan State Medical University, str. Koryun 2, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia, +374 10 582532, marina.safaryan@gmail.com

Armen G. Mkhitaryan, PhD, Associate Professor, Pathologist at the Armenian-German Scientific and Practical Center for Pathology “Histogen”, str. Adonts 6/1, 0001, Yerevan, Armenia; Head of the Laboratory, Armenian-American Health Center Foundation, Chief Pathologist of Yerevan; Senior Lecturer, Department of Pathology, Mkhitar Heratsi Yerevan State Medical University, str. Koryun 2, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia, +374 94 911503, armpath@gmail.com

Hasmik S. Hayrapetyan, Dr. Bio. Sci., Professor at the Department of Medical Genetics, Mkhitar Heratsi Yerevan State Medical University, srt. Koryun 2, 0025, Yerevan, Armenia; Head of the Laboratory of Genetics of Autoinflammatory Diseases, Center for Medical Genetics and Primary Health Care, str. Abovyan 34/3, 0001, Yerevan, Armenia, +374 91 432107, hasmik.hayrapetyan@cmg.am

Corresponding author: Pavel O. Sotskiy, pavel.sotskiy@gmail.com