Pre-treatment before in vitro fertilization and its effectiveness in patients with diffuse adenomyosis

Aim. To conduct preparatory treatment before in vitro fertilization (IVF) program and to assess its effectiveness in patients with various stages of adenomyosis.Aksenenko A.A., Gus A.I., Mishieva N.G., Senina D.N.

Materials and methods. The study included 198 patients with infertility and ineffective past IVF attempts. They were examined and diagnosed with adenomyosis, that could be a possible cause of implantation failure in previous attempts of IVF. 128 patients were randomly divided into three groups. As a preparatory treatment before IVF program, the patients received adenomyosis treatment with GnRH-a, COC and Dienogest in a continuous mode for 3 months. 70 patients did not undergo preparatory treatment before IVF program.

Results. Stage I adenomyosis had no impact on the effectiveness of the IVF program and did not require pre-treatment. At stages II–III adenomyosis, preparatory treatment may increase the conception rate. However, the incidence of pregnancy in women with stage III adenomyosis remains low, and this severe stage of adenomyosis is characterized as the uterine factor of infertility.

Conclusion. Stage I adenomyosis is not the cause of infertility or IVF failures, and does not require pre-treatment. At stages II–III adenomyosis pre-treatment improves the effectiveness of IVF programs.

Keywords

The term adenomyosis is used to describe a form of endometriosis, which is characterized by the spread of glandular and stromal components of the endometrium into the myometrium [1]. Currently, researchers show great interest in the problem of adenomyosis, both in determination of the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease, and assesment of the possible impact of adenomyosis on female reproduction: infertility, miscarriage, and failure of in vitro fertilization (IVF) [2–5]. It is worth noting that researchers are only at the beginning of the way, and they have no clear understanding of what adenomyosis is and how it affects the reproductive function of a woman [6–8].

Despite a rather long history of assisted reproductive technologies for the treatment of various forms of infertility and obvious success of these methods, the pregnancy rate remains the same – approximately 30% per treatment cycle [9]. The specialists are aimed at revealing and overcoming the causes that may affect the effectiveness of IVF programs. Among other causes, the state of the uterus and its ability to implant a fertilized egg and carry a pregnancy are of great importance [10, 11].

The impact of adenomyosis on female reproductive function is still unknown, especially in the initial stages of adenomyosis [12, 13]. Adenomyosis is found in 40–45% of women with unexplained primary infertility and in 50–58% of women with secondary unexplained infertility. Others consider that recurrent miscarriages in 15.3% of women are associated with endometriosis, but whether these data are objective or result from overdiagnosis of pathology, remains a debatable issue [2–4, 6].

Adenomyosis is known to be associated with lower rates of successful implantation and with an increased risk of early pregnancy loss [14–16].

Nevertheless, the relationship between adenomyosis and infertility is unresolved. This provokes new issue, requiring the use of various methods of adenomyosis treatment, both as a therapy itself and as a part of preparation for IVF programs. But so far, the methods of patient preparation have not been fully clarified, and the positive effect of preparatory therapy on the outcomes of IVF programs has not been proven [6–8].

The aim of the study was to conduct preparatory treatment before IVF programs and evaluate its effectiveness in patients with various stages of adenomyosis.

Materials and methods

From March 2018 to January 2020 in the Department of preservation and restoration of reproductive function, 198 patients with adenomyosis were involved in the study based on the order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 107н dated August 30, 2012. 128 women were selected from the study group and treated for adenomyosis for 3 months in preparation to IVF: the 1st group was treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a), the 2nd – with combined oral contraceptives (COCs) and the 3rd – with Dienogest in continuous mode. The comparison group consisted of 70 women of similar age with adenomyosis who had previously undergone IVF without prior preparatory treatment.

The age of women ranged from 22 to 38 years, the median was 34.5 (28; 35) years. All patients had a history of 3 or more ineffective IVF attempts.

The inclusion criteria: reproductive age (22–38 years); normal ovarian reserve; signs of adenomyosis confirmed by ultrasound examination; 3 or more ineffective IVF attempts; possibility of fertilization by IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection into the oocyte (ICSI) according to the results of semen analysis.

Exclusion criteria: criteria regulated by the order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation No. 107н dated August 30, 2012; late reproductive age and rapidly reduced ovarian reserve; severe pathozoospermia in the male partner.

After completion of treatment, the following parameters were evaluated: medication tolerance, clinical and laboratory characteristics, the state of the uterus depending on the stage of endometriosis (confirmed by ultrasound), and pregnancy rate.

To diagnose the stage of adenomyosis, the echographic signs presented in [17] and the adenomyosis classification of the same authors were used.

Diffuse adenomyosis, Stage I:

- thin transverse anechoic stripes expanding in the endometrium from the basal layer to the middle of the M-echo, as well as anechoic inclusions (cysts) in the myometrium and at the border of the endometrium and myometrium;

- increased myometrium hyperechogenicity of various thickness; the presence of anechoic inclusions in the myometrium;

- uneven thickness of the basal layer of the endometrium and “erosion” of the endometrial contours along the basal lamina, which looks like a hypoechogenic endometrial defect; the myometrium behind the basal lamina is not changed;

- the uterus is usually of normal size, but different thicknesses of the anterior and posterior walls of the uterus can be detected;

- the reduced echogenicity areas in the endometrium and small hyperechogenic lesions in the myometrium adjunct to the endometrium.

Diffuse adenomyosis, Stage II:

- an increase in the transverse size of the uterus that exceeds the upper limit of normal thickness;

- an increase in the thickness of one of the walls of the uterus compared to the other by 4 mm or more;

- the presence in the myometrium (closer to the uterine cavity) of zones with areas of heterogeneous echogenicity (increased or decreased) of various extension;

- the presence of small round anechoic lesions 2-5 mm in diameter inside the areas of increased echogenicity;

- the presence of anechoic cavities of various shapes and sizes, containing a fine-dispersed suspension (blood), and sometimes dense inclusions of low echogenicity (blood clots);

- endometrial thickness is usually reduced and does not correspond to the day of the menstrual cycle (due to compression of the endometrium by altered myometrium);

- the presence of cross striation with moderate and low echogenicity at the lesion site;

- ultrasound wave attenuates behind the pathological lesion.

Diffuse adenomyosis, Stage III:

- significant increase in the size of the uterus, mostly anteroposterior;

- reduced thickness of one of the walls of the uterus compared to the other by 10 mm or more;

- the myometrium of an increased heterogeneous echogenicity areas, exceeding half of the thickness of the uterine wall;

- a zone of increased echogenicity in the area of the frontal scanning and of anechoic zone – in the distal scanning.

Clinical, laboratory, and instrumental examination were used in the study. IVF programs in the “long” protocol with GnRH-a and in the protocol with GnRH antagonists were performed according to the general rules that determine the dose of gonadotropins depending on the parameters of the ovarian reserve. Human chorionic gonadotropin at a dose of 10,000 units was used as a trigger for the final maturation of oocytes.

Statistical analysis

The statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics v22 (IBM Corp., USA) was used for statistical processing.

All obtained quantitative parameters were tested for their compliance with the normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Numerical parameters with normal distribution are presented as M(SD), where M is the mean value, SD is the standard deviation of the mean value. Parameters with a distribution other than normal are presented as Me (Q25%; Q75%), where Me is the median and Q25% and Q75% are the upper and lower quartiles.

Qualitative data are presented in both absolute and relative values (%).

To find the differences between groups of patients for normally distributed numbers we used ANOVA test (for several groups with equal variances) and then performed pairwise comparison of groups using the Student's t-test for two independent samples with Bonferroni correction for continuity. If the hypothesis of normal distribution was not confirmed, quantitative data were compared by nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test (for several groups), and then pairwise comparison of groups was performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test for unrelated combinations. For multiple comparisons, Bonferroni correction was used.

To determine the differences in the numerical indicators that changed during the treatment we used the paired Student's test for two dependent samples; in the absence of normal distribution we used the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

To compare dichotomous indicators between independent samples, we used the χ2 method with Yates' correction for continuity, and Fisher's exact test for small samples. If the χ2 method could not be used, the Z-criterion (an analogue of Student's t-test for fractions) was used, and for 0% and 100% the method with endpoint correction was used.

The critical level of significance for statistical hypothesis testing was assumed to be 0.05.

Results and discussion

Numerous studies have shown that ultrasound is currently the most reliable diagnostic method for detecting adenomyosis [17, 18]. Ultrasound examination was performed twice: on the 5–7th and 19–22nd days of the menstrual cycle. Signs associated with adenomyosis were found in all studied patients.

These signs were represented by the following changes in the uterus: enlargement of the uterus mainly in the anteroposterior size, and asymmetric thickening of one of the walls – in 128/128 (100%) women; areas of increased echogenicity of round or oval shape in the myometrium, anechoic areas or cystic cavities with a fine-dispersed suspension – in 108/128 (84.4%) women; indistinct boundaries of the uterine cavity (uneven thickness of the basal layer of the endometrium, serration) – in 65/128 (50.8%); areas of increased echogenicity in the myometrium with linear acoustic shadows – in 49/128 (38.3%); hyperechogenic linear structures on the border of the endometrium and myometrium – in 37/128 (28.9%).

Stage I was observed in 50/128 (39.1%) patients in the study group, stage II – in 52/128 (40.6%) patients, stage III – in 26/128 (20.3%) patients. The patients of the study group (128 women) were randomly divided into 3 subgroups:

A. 38 patients who received 3 depot injections of GnRH-a (triptorelin at a dose of 3.75 mg).

B. 45 women who received COCs containing 30 mcg ethinylestradiol and 2 mg Dienogest. The medication was administered for 3 months continuously.

C. 45 women who received Dienogest at a dose of 2 mg per day, continuously for 3 months.

The comparison group (70 patients) was also divided depending on the stages of adenomyosis: stage I in the comparison group was observed in 30/70 (42.9%) patients, stage II – in 22/70 (31.4%) patients, stage III – in 18/70 (25.7%) patients.

The distribution of patients according to the stages of adenomyosis did not differ significantly between the groups. The number of women with adenomyosis of stage I and stage II was prevailing in all groups and amounted to 30/38 (79%) in group A, 36/45 (80%) in group B, and 36/45 (80%) in group C. Treatment was given regardless the severity of adenomyosis and was started on the 2nd or 3rd day of the menstrual cycle; the pills were prescribed one per every night, without a break for 3 months. The first injection of GnRH-a was administered on the 2nd –3rd day of the menstrual cycle, the next two injections were administered 28-30 days after the previous one. Medication tolerance was analyzed by assessing a number of parameters, including the spotting bleeding, the characteristics of menstrual-like bleedings, treatment tolerance, and the presence of neurovegetative symptoms.

The data showed that patients of group A (receiving GnRH-a) had primarily autonomic disorders: hot flashes, increased BP, bone pain, headaches, depression; the patients of the other two groups (receiving COCs and Dienogest, respectively) had abnormal uterine bleeding. However, in patients of group A, autonomic and metabolic disorders increased with the duration of treatment, while the side effects observed in patients receiving COCs and Dienogest resolved by the end of the third month of treatment, which allows prolongation of treatment duration.

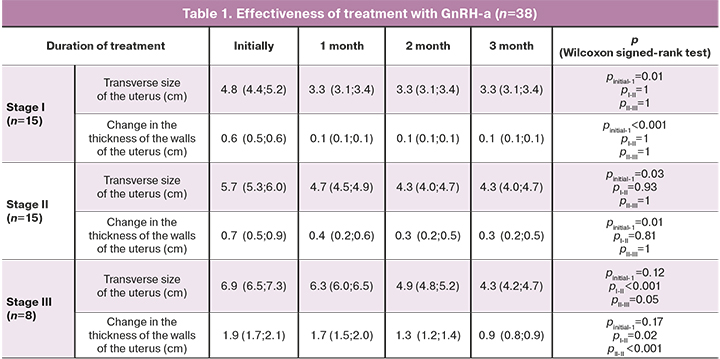

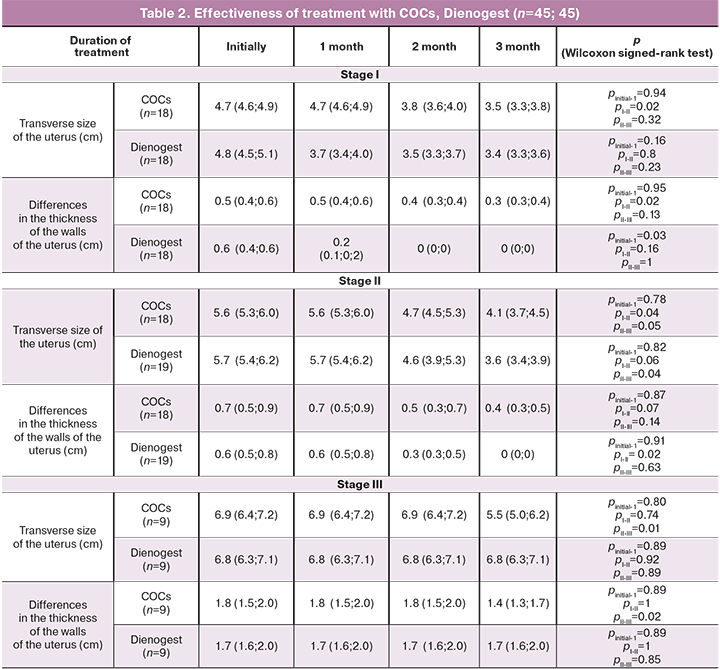

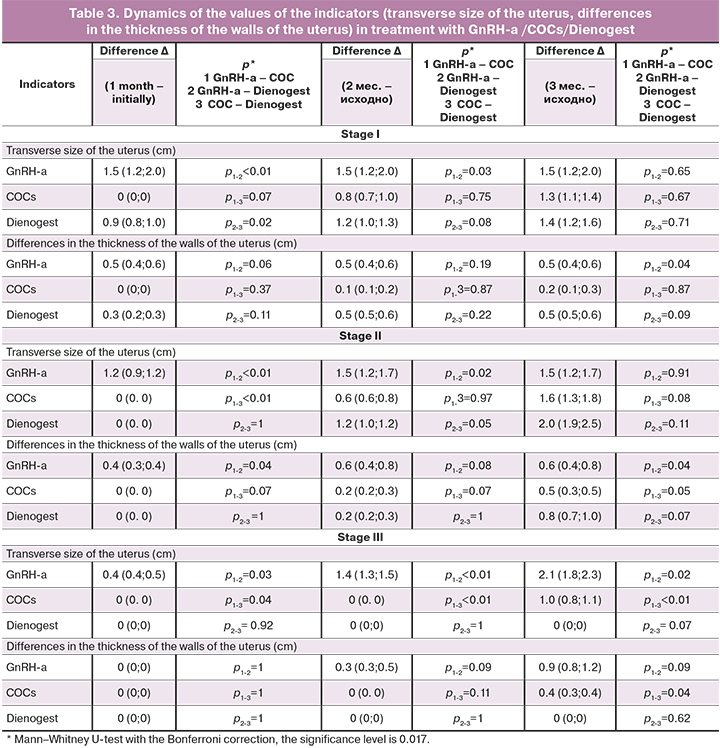

Control ultrasound was performed every month of treatment to assess the effectiveness. The data are presented in Tables 1 and 2, which show the assessment of the treatment, depending on the stage of the disease and the type of therapy.

The data show that the therapeutic effect of GnRH-a in patients with stages I–II of adenomyosis was reached in the first month of treatment, since at stage I of adenomyosis the thickness of the uterine walls decreased from 4.8 cm (4.4; 5.2) to 3.3 cm (3.1; 3.4), (p=0.01), and the uterus size became normal. A decrease in the hypoechogenicity area at the periphery of the endometrial border was noted, but hypo- and anechoic structures in the myometrium was still visualized. In the next 2 months, despite continuing treatment, the ultrasound picture did not change.

In stage II of adenomyosis, the uterus reached normal size during the first 2 months of treatment: the wall thickness decreased from 5.7 cm (5.3; 6.0) to 4.3 cm (4.0; 4.7), (p=0.03), the area of increased echogenicity of the basal layer decreased, hyperechogenic and anechoic inclusions in the myometrium remained. Further treatment did not lead to a pronounced therapeutic effect, the state of the uterus in ultrasound remained unchanged.

Thus, the therapeutic effect of GnRH-a in stage I–II of adenomyosis was reached at 1–2 month of treatment, and further therapy did not lead to significant changes in the echographic picture, but endocrine and metabolic disorders became more severe. In women with stage III of adenomyosis, the therapeutic effect was reached only after the third month of treatment with GnRH-a, when the uterine size became normal, and the thickness of the hyperechogenic area in the myometrium reduced twice (from 3 cm to 1.4 cm). However, hyperechogenic and anechoic inclusions in the myometrium remained.

The therapeutic effect of COCs in women with stages I–II of adenomyosis was manifested only in the 2nd month of taking the pills. By the end of the 3rd month of treatment, in women with stage I of adenomyosis the uterus reached almost normal size, although in women with stage II of adenomyosis, the transverse size of the uterus remained more than normal.

In patients with stage III of adenomyosis, the therapeutic effect of COCs was poor. Only by the 3rd month of treatment the thickness of the uterine walls decreased from 6.9 cm (6.4; 7.2) to 5.5 cm (5.0; 6.2), the other signs of adenomyosis such as hyperechogenic area in the myometrium, and presence of hyper- and anechoic inclusions remained.

Treatment with Dienogest led to a decrease in the size of the uterus in women with stages I–II of adenomyosis. At stage I, the uterus reached normal size after the 1st month of taking the medication, at stage II, the uterus size decreased after 2 months of treatment, and after 3 months of treatment the uterus reached normal size. In women with stage III of adenomyosis the therapeutic effect was not observed even after 3 months of taking the medication.

The study indicates that the treatment of COCs and Dienogest in a continuous regimen is therapeutically reasonable in patients with stages I–II of adenomyosis, because the uterus reached normal size by the end of the 3rd month of treatment, side effects of “spotting” are eliminated and endocrine metabolic disorders are absent.

This type of treatment in women with stage III of adenomyosis did not improve the situation after 3 months of treatment; this may be an indication that therapy should be prolonged for 6 months or more.

In women with stages I–II of adenomyosis, a decrease in the size of the uterus was achieved after 1 month of treatment with GnRH-a, further treatment led only to the development or worsening of endocrine and metabolic disorders without pronounced changes in the uterus. In women with stage III of adenomyosis, only the use of GnRH-a led to the therapeutic effect by the end of the 3rd month of treatment. These results allow us to conclude that a differentiated approach to the choice of the method for treating adenomyosis (depending on its stage) is necessary. At stages I–II of adenomyosis the use of COCs or Dienogest for 3 months continuously is preferable. Treatment with Dienogest had a more pronounced therapeutic effect and fewer complications. In women with stage III of adenomyosis, these treatments should rather be used for at least 6 months. The therapeutic effect by the end of the 3rd month of treatment at this stage of adenomyosis was reached only with GnRH-a.

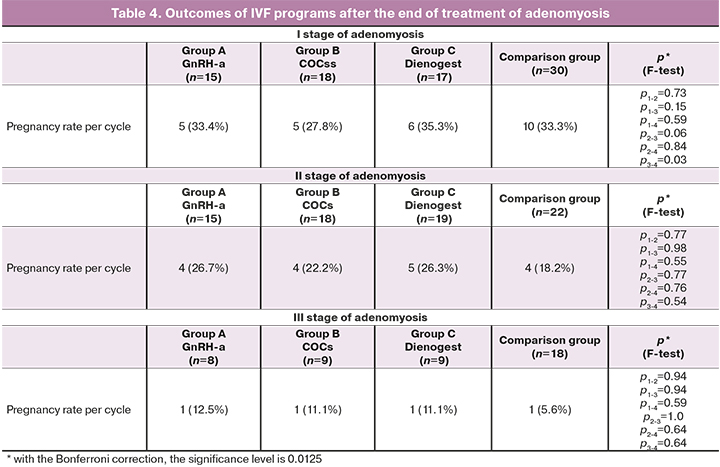

At the next step of our study, after the end of treatment, an IVF program was carried out, and the pregnancy rate was evaluated.

The pregnancy rate in women with stage I of adenomyosis was 5/15 (33.4%) in group A, 5/18 (27.8%) in group B, and 6/17 (35.3%) in group C, which corresponded to the indicators of patients without preparatory treatment – 10/30 (33.3%), (p>0.05). Thus, in patients with stage I of adenomyosis, regardless of the type of preparatory therapy (GnRH-a, Dienogest, COCs), the results of IVF programs were almost the same as in the comparison group.

In women with stage II of adenomyosis, the pregnancy rate (pregnancies per treatment attempt) was 4/15 (26.7%) in group A, 4/18 (22.2%) in group B, 5/19 (26.3%) in group C, and 4/22 (18.2%) in the comparison group (p>0.05). In patients with stage II of adenomyosis the pregnancy rate was higher than in comparison group. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the pregnancy rate depending on the type of preparatory therapy.

In women with stage III of adenomyosis, regardless of the preparatory therapy, an increase in the pregnancy rate compared to the comparison group was observed. However, the results remain low and do not exceed 11–12%. The pregnancy occurred in 1/8 (12.5%) women in group A, in 1/9 (11.1%) women in group B, in/6 (11.1%) women in group C, and in 1/17 (5.6%) women in the comparison group (p>0.05).

Conclusion

Serial ultrasound examination showed that in patients with stage I of adenomyosis, all 3 types of treatment did not lead to a significant change in the state of the uterus within 3 months of treatment. The pregnancy rate per IVF attempt in stage I of adenomyosis does not depend on treatment regardless of its type. Consequently, stage I of adenomyosis is not the cause of infertility and IVF failures, and does not require treatment.

In women with stage II of adenomyosis, preparatory treatment can increase the pregnancy rate by 5-8% compared to the control group. The preferable medication in this case is Dienogest, which has a satisfactory therapeutic effect and minimal side effects.

In case of stage III of adenomyosis, the use of preparatory treatment with GnRH-a increased the pregnancy rate from 5 to 12% per IVF attempt, while treatment with COCs and Dienogest did not lead to a significant therapeutic effect, and the state of the uterus remained practically unchanged. However, the pregnancy rate remains low, which allowed us to define stage III of adenomyosis as cause of severe uterine infertility.

References

- Benagiano G., Habiba M., Brosens I. The pathophysiology of uterine adenomyosis: an update. Fertil. Steril. 2012; 98(3): 572-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.044.

- Atabekoğlu C.S., Şükür Y.E., Kalafat E., Özmen B., Berker B., Aytaç R., Sönmezer M. The association between adenomyosis and recurrent miscarriage. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020; 250: 107-11. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.05.006.

- Buggio L., Monti E., Gattei U., Dridi D., Vercellini P. Adenomyosis: fertility and obstetric outcome. A comprehensive literature review. Minerva Ginecol. 2018; 70(3): 295-302. https://dx.doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4784.17.04163-6.

- Tamura H., Kishi H., Kitade M., Asai-Sato M., Tanaka A., Murakami T., Minegishi T., Sugino N. Clinical outcomes of infertility treatment for women with adenomyosis in Japan. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2017; 16(3): 276-82. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rmb2.12036.

- Liang Z., Yin M., Ma M., Wang Y., Kuang Y. Effect of pretreatment with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on IVF and vitrified-warmed embryo transfer outcomes in women with adenomyosis. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2019; 39(1): 111-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.03.101.

- Benagiano G., Brosens I., Habiba M. Adenomyosis: a life-cycle approach. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2015; 30(3): 220-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.11.005.

- Yen C.F., Huang S.J., Lee C.L., Wang H.S., Liao S.K. Molecular characteristics of the endometrium in uterine adenomyosis and its biochemical microenvironment. Reprod. Sci. 2017; 24(10): 1346-61. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1933719117691141.

- Garavaglia E., Audrey S., Annalisa I., Stefano F., Iacopo T., Laura C., Massimo C. Adenomyosis and its impact on women fertility. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2015; 13(6): 327-36.

- Корсак В.С., ред. Регистр ВРТ РАРЧ. Отчет за 2018 год. Санкт-Петербург; 2020. 55с. [Korsak V.S., ed. Register of ART RARCH. Report for 2018. St. Petersburg, 2020. 55 p. (in Russian).

- Wu F., Liu F., Guan Y., Du J., Tan J., Lv H. et al. A nomogram predicting clinical pregnancy in the first fresh embryo transfer for women undergoing in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI) treatments. J. Biomed. Res. 2019; 33(6): 422-9.

- Seshadri S., Sunkara S.K. Natural killer cells in female infertility and recurrent miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2014; 20(3): 429-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt056.

- Moore J., Kennedy S., Prentice A. Modern combined oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000; (2): CD001019. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001019.

- Адамян Л.В., Кулаков В.И., Андреева Е.Н. Эндометриозы. Руководство для врачей. М.: Медицина; 2006. 416с. [Adamyan L.V., Kulakov V.I., Andreeva E.N. Endometriosis: A Guide for Physicians. M.: JSC "Publishing house Medicine", 2006. 416 р. (in Russian)].

- Younes G., Tulandi T. Effects of adenomyosis on in vitro fertilization treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2017; 108(3): 483-90. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.025.

- Bourdon M., Santulli P., Oliveira J., Marcellin L., Maignien C., Melka L. et al. Focal adenomyosis is associated with primary infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2020; 114(6): 1271-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.018.

- Mavrelos D., Holland T.K., O’Donovan O., Khalil M., Ploumpidis G., Jurkovic D., Khalaf Y. The impact of adenomyosis on the outcome of IVF-embryo transfer. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2017; 35(5): 549-54. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.06.026.

- Демидов В.Н., Гус А.И., Адамян Л.В., Хачатрян А.К. Эхография органов малого таза у женщин. Вып. 1. Эндометриоз. Практическое пособие. М.: ИИФ «Скрипто»; 1997. 60с. [Demidov V.N., Gus A.I., Adamyan L.V., Khachatryan A.K. Echography of the pelvic organs in women. Endometriosis: A Practical Guide. M.: "Scripto", 1997. 60 p. (in Russian)].

- Campbell S. Ultrasound evaluation in female infertility: Part 2: The uterus and implantation of the embryo. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2019; 46(4): 697-713. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2019.08.002.

Received 26.03.2021

Accepted 28.04.2021

About the Authors

Artem A. Aksenenko, gynecologist of the 1st Gynecology Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russian Federation. E-mail: a_axenenko@oparina4.ru. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.Alexandr I. Gus, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department Ultrasound Diagnostic Imaging, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center

for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russian Federation. E-mail: a_gus@oparina4.ru. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Nona G. Mishieva, PhD, Senior researcher of 1st Gynecology Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(495)438-26-22. E-mail: nondoc555@mail.ru. 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Daria N. Senina, clinical resident, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russian Federation. Tel.: +7(904)189-30-63. E-mail: Seninadasha1995@gmail.ru. 117997 Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str. 4.

For citation: Aksenenko A.A., Gus A.I., Mishieva N.G., Senina D.N. Pre-treatment before in vitro fertilization and its effectiveness in patients with diffuse adenomyosis.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/ Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021; 7: 113-120 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.7.113-120