Perinatal outcomes of monochorionic multigestational pregnancies with different types of selective fetal growth restriction

Gladkova K.A., Frolova E.R., Sakalo V.A., Kostyukov K.V.

Background: Selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR) complicates 10–15% of pregnancies with monochorionic twins and is characterized by discordant fetal growth and a high level of perinatal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. sFGR is classified into three types according to the Doppler pattern of blood flow in the umbilical artery (UA) in growth-restricted twins. Each type is associated with a specific clinical course and perinatal and neonatal outcomes and differs in the degree of uneven placental separation and the functioning of placental-vascular anastomoses.

Objective: To assess the perinatal outcomes of expectant management of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies complicated by sFGR according to the type of UA blood flow disorder in growth-restricted twins.

Materials and methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted at V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia from January 2017 to January 2024. The course of pregnancy in 128 women with monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies complicated by sFGR was analyzed. Group 1 included patients with type I sFGR (n=72), group 2 included patients with type II sFGR (n=37), and group 3 included patients with type III sFGR (n=19).

Results: Perinatal parameters varied depending on the sFGR type. Antenatal fetal growth discordance was significantly different from the first trimester of pregnancy in types I and II sFGR, with the highest discordance observed in group 2. The age at delivery in sFGR type I was greater than that in types II and III (34.2, 31.4 and 31.6 weeks, respectively; p<0.001). Type II sFGR was characterized by the worst outcomes, including the highest discordance in neonatal body weight (42.9%, p<0.001) and the lowest length/height-for-age indicators of growth-restricted children– 988.5 g, 36 cm; body weight: p1/2<0.001, p2/3=0.0012, length: p1/2<0.001, p2/3=0.049). The proportion of children with growth restriction and severe and moderate birth asphyxia (Apgar score<5) was significantly higher in types II and III sFGR. In our study, the overall survival rate was 92.2% (20 children died, including 6 (2.34%) antenatally and 14 (5.5%) postnatally). Antenatal fetal death with growth restriction occurred in four cases (1.56%) with sFGR types I and II and co-twin death in one patient in group 2. Statistically significant adverse perinatal outcomes (χ2=19.713; p=0.003) were observed for sFGR type II.

Conclusion: The course of multigestational pregnancies complicated by type II sFGR is characterized by the most adverse perinatal outcomes. The classification of sFGR according to the type of UA blood flow disorder should form the basis for an individual management plan for pregnant women, with the level of observation corresponding to the degree of risk for perinatal loss.

Authors' contributions: Gladkova K.A. – conception and design of the study, review of the relevant literature, structuring and drafting of the manuscript; Kostyukov K.V. – material collection, data analysis, editing of the manuscript; Frolova E.R., Sakalo V.A. – data acquisition for analysis and statistical analysis, drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: There was no funding for this study.

Ethical Approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Gladkova K.A., Frolova E.R., Sakalo V.A., Kostyukov K.V. Perinatal outcomes of monochorionic multigestational pregnancies with different types of selective fetal growth restriction.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (1): 35-43 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.322

Keywords

Selective fetal growth restriction (sFGR) complicates 10–15% of pregnancies with monochorionic diamniotic (MCDA) twins [1–3]. sFGR is associated with an increased risk of intrauterine fetal demise in growth-restricted fetuses, which can lead to death or severe neurological damage in larger twins [4, 5]. The pathophysiology of sFGR and its complications is closely related to unequal placental sharing between fetuses and blood flow between twins through functioning placental anastomoses [6]. Based on blood flow changes, sFGR can be classified into three types [7]. Type I is characterized by positive end-diastolic flow (EDF) in the umbilical artery (UA) and is usually associated with relatively good outcomes; Type II is characterized by zero or reverse EDF in the UA and is associated with increased perinatal mortality and morbidity; and Type III is characterized by periodic zero/reverse EDF in the UA and is marked by an unpredictable clinical course due to acute feto-fetal transfusion catastrophes through large arterio-arterial anastomoses as well as a high risk of developing neurological disorders in children [8–12].

Current imaging technologies cannot accurately predict the development of complications; however, ultrasound and Doppler studies reveal early signs of pathological conditions. Evidence is currently accumulating on the influence of angiogenic factors on maternal-fetal circulation and placentation, as well as their predictive role as markers of placental dysfunction. However, their significance in multiple pregnancies has not been studied and requires a comprehensive analysis [13, 14].

The optimal management strategies for patients with MCDA twins complicated with sFGR remain unclear. Treatment options include expectant management, selective reduction of the growth-restricted fetus, and fetoscopic laser coagulation of placental vascular anastomoses [1, 15]. The results of active management strategies are not clearly effective in improving perinatal outcomes in sFGR, leading most experts to consider expectant management of pregnancy as the more reasonable option [16, 17].

Therefore, the main objective of this study was to analyze the course of pregnancy and assess perinatal outcomes in the expectant management of monochorionic twins complicated by sFGR according to the type of UA blood flow disorder in growth-restricted twins.

Materials and methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of Russia from January 2017 to January 2024. The course of pregnancy in 128 pregnant women with MCDA twins complicated by sFGR was analyzed. Cases were classified based on the EDF in the UA according to the classification proposed by Gratacos et al. (2007) [7]. Group 1 (n=72, 56.25%) included patients with type I (positive EDF in the UA of the growth-restricted fetuses; group 2 (n=37, 28.9%) consisted of those with type II (zero or reverse EDF in the UA); and group 3 (n=19, 14.85%) included patients with type III (intermittent EDF in the UA) sFGR.

The inclusion criteria were MCDA twins complicated by sFGR, with observation and delivery at the V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of Russia.

Exclusion criteria were dichorionic twins, monoamniotic twins, multiple pregnancies of the highest order (triplets, quadruplets), twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, and anemia-polycythemia syndrome.

Gestational age was determined based on the first day of the last menstrual period and the crown-rump length (CRL) of the larger fetus during ultrasound examination (US) at 11–14 weeks. In cases of pregnancy resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF), the date of transfer and days of embryo culture were used to establish gestational age. Chorionicity was determined using ultrasonography in the first trimester. The diagnosis of sFGR was based on the following echographic criteria: estimated fetal weight (EFW) of one of the fetuses less than the 3rd percentile, or EFW of one of the fetuses less than the 10th percentile combined with at least one of the following criteria: abdominal circumference less than the 10th percentile, a difference in EFW of the fetuses ≥25%, or impaired blood flow in the umbilical artery [3, 18].

To assess the condition of the fetuses, the patients underwent dynamic monitoring of ultrasound parameters (Voluson ultrasound device, GE Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) every two weeks, starting from the 16th week of pregnancy. Fetal biometric parameters, fetal anatomy, amniotic fluid volume, blood flow in the UA, venous duct, middle cerebral artery, uterine arteries, and cervical length were also evaluated. The discordance of the EFW was calculated using the formula: ((EFW of the larger fetus - EFW of the smaller fetus) / EFW of the larger fetus) × 100 [3]. Doppler UA ultrasonography was performed both in the free loop and closer to the placenta. If different flow patterns were observed in both the UAs, a more severe pattern was used to classify the sFGR type. To exclude anemia-polycythemia syndrome, maximum systolic velocity in the middle cerebral artery was measured. Doppler evaluation of the venous duct was performed in the absence of fetal movements and classified as positive, negative, or reverse a-wave. Doppler parameters were monitored weekly beginning at 26 weeks of gestation. From 30 weeks onward, all patients underwent weekly fetal cardiotocography (CTG) weekly. The concentrations of placental growth factor (PlGF) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) in the serum were determined using the Elecsys PLGF and Elecsys sFlt-1 electrochemiluminescent diagnostic test systems (Hoffmann-La Roche, Switzerland) on a Cobas-e 411 automatic analyzer (Kone, Finland).

Patients with type II and III sFGR were hospitalized at 30 weeks gestation. For type I sFGR, hospitalization was recommended at 33–34 weeks. In the hospital setting, fetal respiratory distress syndrome was prevented by administering 24 mg of dexamethasone intramuscularly. CTG monitoring was performed daily, and Doppler ultrasound was conducted two–three times a week for type I sFGR and daily for types II and III. In the absence of deterioration in fetal condition, a planned cesarean section was performed for type I at 34–35 weeks and for types II and III at 31–32 weeks of pregnancy. Newborns were examined and treated in the neonatal intensive care unit.

The study analyzed the course of pregnancy (including clinical and anamnestic data, gestational complications, and fetal growth indices according to ultrasound findings) and assessed perinatal outcomes (gestational age at delivery, intrauterine and early neonatal death of fetuses, and weight and height indices of newborns).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software (version 26.0). Descriptive statistics for categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages (n, %) as well as the median and interquartile range (Me [Q1; Q3]). The significance of differences in interval and ordinal indicators for three or more groups was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by multiple pairwise comparisons using the Mann–Whitney test to clarify the nature of the differences. Statistical hypotheses were tested at a critical significance level of 0.017, accounting for the Bonferroni correction. The Student’s t-test was used to compare variables between two groups with normal distribution and equal variances. Differences were considered statistically significant at a significance level of p<0.05.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P of the Ministry of Health of Russia.

Results

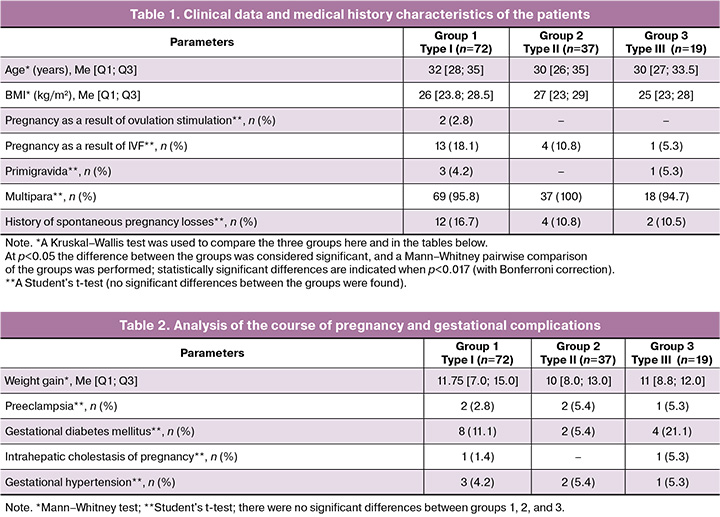

When analyzing the clinical data and medical history of the patients, we found no differences between the groups in terms of age, body mass index (BMI), method of conception, and parity. Detailed information on clinical data and medical history is presented in Table 1.

Analysis of the pregnancy course in the study groups, particularly regarding complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, did not reveal statistically significant differences. The structure and frequency of the gestational complications and drug support are presented in Table 2.

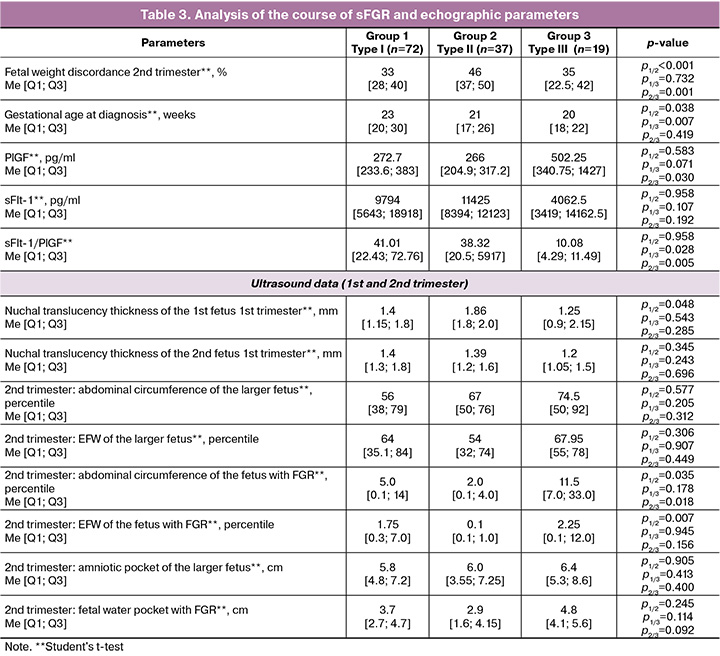

Given the increased risk of developing specific complications in monochorionic twins, regular fetal monitoring is fundamentally important for antenatal care in multiple pregnancies. The average time for sFGR diagnosis was 20–23 weeks across all groups and was significantly earlier in groups 2 and 3 of the study. When analyzing fetal biometric parameters at 18–22 weeks of pregnancy, a decrease in the growth rate of the growth-restricted fetus and maximum discordance of the EFW (46%, p<0.001) were noted in type II sFGR.

The introduction of angiogenesis markers into obstetric practice as predictors of adverse perinatal outcomes has led to the study of PlGF and sFlt-1 levels and their ratio in the third trimester of pregnancy. The statistically significant increase in PLGF levels in type III sFGR is noteworthy and requires further in-depth investigation to validate the indicators for multiple pregnancies and uncomplicated multiple pregnancies. The detailed information is presented in Table 3.

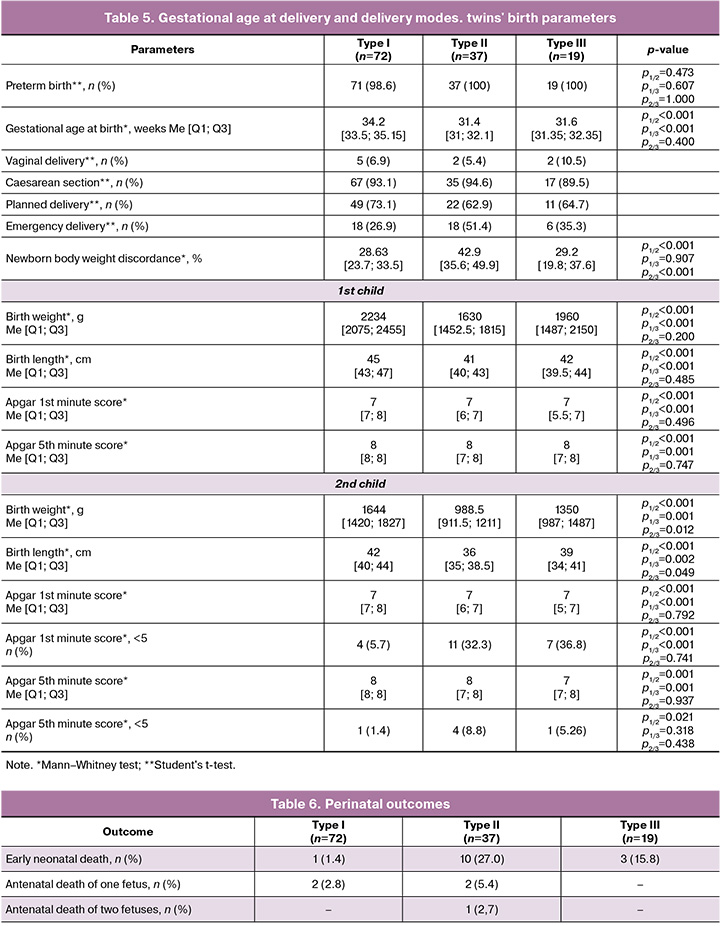

The analysis of fetal growth in the groups revealed statistically significant discordance in fetal size starting from the first trimester of pregnancy in sFGR types I and II, as well as in all groups during the second trimester and at birth (Table 4).

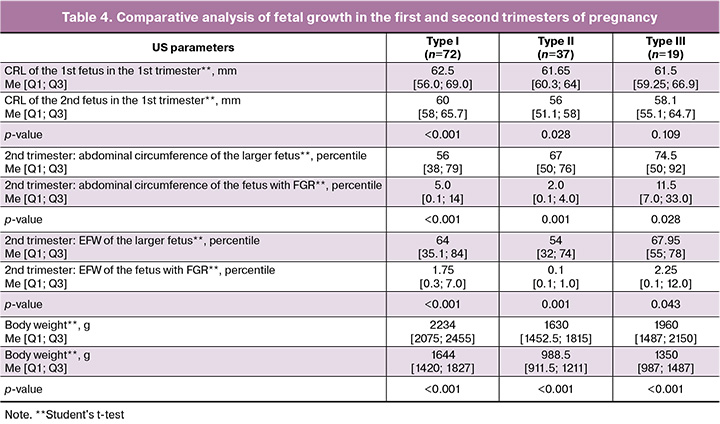

Summary data on perinatal outcomes are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Patients in groups 2 and 3 delivered prematurely in 100% of cases. The operative abdominal delivery rate in all groups was 90%. Overall, the most favorable outcomes were observed with sFGR type I, with a longer gestational age at delivery, which was significantly different from the other groups (p<0.001): 34.2, 31.4, and 31.6 weeks, respectively. sFGR type II was characterized by the worst outcomes, including the highest discordance in twin body weight at 42.9% (p<0.001) and the lowest length/height-for-age indicators for growth-restricted newborns. According to the obtained data, sFGR type III showed relatively similar results to those of type II, although slightly better. Despite having the same gestational age at delivery, the birth weights of growth-restricted newborns were significantly higher. The proportion of growth-restricted infants with severe and moderate birth asphyxia (< 5 points on the Apgar scale) was significantly higher (p<0.001) in types II and III. This is presumably due to an earlier gestational age at delivery, lower birth weight, and antenatal hypoxia, which require further study.

Intrauterine death of one growth-restricted fetus occurred in four cases (3.25%) – two in group 1 (at 27.6 and 32 weeks) and two in group 2 (at 30 and 32 weeks of pregnancy). Antenatal death in both fetuses was diagnosed in one patient in group 2 (0.8%) at 31.1 weeks of pregnancy. In our study, 14 children died after birth: one (0.7%) in group 1, ten (14.3%) in group 2, and three (7.9%) in group 3 (Table 5). The overall survival rate was 92.2% (a total of 20 children died: six (2.34%) prenatally and 14 (5.5%) postnatally). A favorable perinatal outcome was observed in 69/72 (95.8%) patients in group 1, 24/37 (64.9%) in group 2, and 16/19 (84.2%) in group 3; significantly worse survival rates were noted in type II sFGR (χ2=19.713; p=0.003).

Discussion

In our study, the classification system based on the Doppler pattern of UA blood flow changes in growth-restricted fetuses was consistent with the perinatal outcomes. Pregnancies complicated by sFGR type II were associated with significantly greater discordance between fetal and neonatal body weights and were statistically associated with poorer outcomes. Additionally, pregnancy outcomes in patients in groups 2 and 3 were characterized by earlier delivery, lower birth weights, and reduced Apgar scores for newborns compared with those in group 1. The relationship we identified between the classification of sFGR according to the Doppler pattern of UA blood flow and perinatal outcomes aligns with previously published studies showing that type II sFGR has the most unfavorable prognosis [8–10, 19]. A major challenge in managing monochorionic multiple pregnancies with sFGR is the lack of specific, confirmed, and well-established prognostic factors for adverse perinatal outcomes. Based on the assessment of pregnancy progression and ultrasound examination parameters, most authors suggest that an earlier gestational age at the time of diagnosis of type II sFGR, combined with twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, is significantly associated with an increased risk of fetal and neonatal death in smaller twins [9, 10, 19, 20].

Recent publications have confirmed that specific complications of monochorionic multiple pregnancies are associated with abnormal placentation, ischemia, and/or hypoxemia [13, 21]. A hypoxic environment promotes the excretion of antiangiogenic factors, such as sFlt-1, while simultaneously reducing the bioavailability of proangiogenic factors, such as PlGF [14]. In recent decades, the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio has been studied and widely introduced into routine practice as an indicator of placental dysfunction with detectable changes before the onset of clinical manifestations [22]. Currently, there is a focus on the search for and validation of molecular biological predictors of perinatal loss. In our study, we examined the levels of sFlt-1 and PlGF during the third trimester of pregnancy. The sFlt-1 levels significantly exceeded the reference values for a singleton uncomplicated pregnancy, with the median sFlt-1/PlGF ratio corresponding to the established standards. Notably, there was a statistically significant increase in PLGF levels in type III sFGR. Further investigation into the role of angiogenesis markers in predicting maternal and fetal complications will help identify groups of patients at a high risk of perinatal losses. The results of this study align with recent publications and enhance our ability to predict perinatal outcomes in monochorionic multiple sFGR pregnancies, indicating that an earlier gestational age at diagnosis of type II sFGR and greater fetal-neonatal weight dissociation are significantly associated with a higher risk of preterm birth (<32 weeks) and worse perinatal prognosis [23, 24].

Our results can be utilized to effectively counsel perinatal outcomes and make informed decisions regarding preferred pregnancy management strategies. Pregnancy complicated by type II sFGR has the worst prognosis, with an increased risk of antenatal and neonatal fetal death, and iatrogenic preterm birth. In such cases, early hospitalization at 30 weeks and daily fetal monitoring may lead to a reduction in adverse outcomes by enabling the timely detection of fetal decompensation associated with sFGR and facilitating emergency delivery.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is important to recognize that monochorionic multiple pregnancies complicated by sFGR are high-risk conditions that necessitate strict dynamic monitoring. Classifying sFGR based on the type of blood flow abnormalities in the UA should be the basis for an individualized management plan for pregnant women, ensuring that the level of monitoring aligns with the degree of perinatal loss risk. Further studies are needed to assess the cost-effectiveness of planned hospitalization for patients with MCDA complicated by sFGR, and to determine the ideal timing and triggers for delivery.

References

- Valsky D.V., Eixarch E., Martinez J.M., Crispi F., Gratacós E. Selective intrauterine growth restriction in monochorionic twins: pathophysiology, diagnostic approach and management dilemmas. Semin. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2010; 15(6): 342-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2010.07.002.

- Lewi L., Jani J., Blickstein I., Huber A., Gucciardo L., Van Mieghem T. et al. The outcome of monochorionic diamniotic twin gestations in the era of invasive fetal therapy: a prospective cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008; 199(5): 514.e1-514.e8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.050.

- Khalil A., Rodgers M., Baschat A., Bhide A., Gratacos E., Hecher K. et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: role of ultrasound in twin pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016; 47(2): 247-63. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.15821.

- Lopriore E., Sluimers C., Pasman S.A., Middeldorp J.M., Oepkes D., Walther F.J. Neonatal morbidity in growth-discordant monochorionic twins: comparison between the larger and the smaller twin. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2012; 15(4): 541-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/thg.2012.26.

- Костюков К.В., Гладкова К.А. Перинатальные исходы при монохориальной многоплодной беременности, осложненной синдромом селективной задержки роста плода. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 6: 50-8. [Kostyukov K.V., Gladkova K.A. Perinatal outcomes of monochorionic multiple pregnancies with selective intrauterine growth restriction. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (6): 50-8 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.6.50-58.

- Фролова Е.Р., Гладкова К.А., Туманова У.Н., Сакало В.А., Костюков К.В., Ляпин В.М., Щеголев А.И., Ходжаева З.С. Морфологическая характеристика плаценты при монохориальной диамниотической двойне, осложненной синдромом селективной задержки роста плода. Проблемы репродукции. 2023; 29(1): 79-85. [Frolova E.R., Gladkova K.A., Tumanova U.N., Sakalo V.A., Kostyukov K.V., Lyapin V.M., Shchegolev A.I., Khodzhaeva Z.S. Placental characteristics of selective fetal growth restriction in monochorionic diamniotic twins. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2023; 29(1): 79-85. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro20232901179.

- Gratacós E., Lewi L., Muñoz B., Acosta-Rojas R., Hernandez-Andrade E., Martinez J.M. et al. A classification system for selective intrauterine growth restriction in monochorionic pregnancies according to umbilical artery Doppler flow in the smaller twin. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2007; 30(1): 28-34. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.4046.

- Ishii K., Murakoshi T., Takahashi Y., Shinno T., Matsushita M., Naruse H. et al. Perinatal outcome of monochorionic twins with selective intrauterine growth restriction and different types of umbilical artery Doppler under expectant management. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2009; 26(3): 157-61. https://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000253880.

- Batsry L., Matatyahu N., Avnet H., Weisz B., Lipitz S., Mazaki‐Tovi S. et al. Perinatal outcome of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy complicated by selective intrauterine growth restriction according to umbilical artery Doppler flow pattern: single‐center study using strict fetal surveillance protocol. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021; 57(5): 748-55. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.22128.

- Buca D., Pagani G., Rizzo G., Familiari A., Flacco M.E., Manzoli L. et al. Outcome of monochorionic twin pregnancy with selective intrauterine growth restriction according to umbilical artery Doppler flow pattern of smaller twin: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017; 50(5): 559-68. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.17362.

- Gratacós E., Carreras E., Becker J., Lewi L., Enríquez G., Perapoch J. et al. Prevalence of neurological damage in monochorionic twins with selective intrauterine growth restriction and intermittent absent or reversed end-diastolic umbilical artery flow. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004; 24(2): 159-63. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.1105.

- Van Mieghem T., Eixarch E., Gucciardo L., Done E., Gonzales I., Van Schoubroeck D. et al. Outcome prediction in monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancies with moderately discordant amniotic fluid. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 37(1): 15-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.8802.

- Sapantzoglou I., Rouvali A., Koutras A., Chatziioannou M.I., Prokopakis I., Fasoulakis Z. et al. sFLT1, PlGF, the sFLT1/PlGF ratio and their association with pre-eclampsia in twin pregnancies – a review of the literature. Medicina (B Aires). 2023; 59(7): 1232. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/medicina59071232.

- Hong J., Kumar S. Circulating biomarkers associated with placental dysfunction and their utility for predicting fetal growth restriction. Clin. Sci. 2023; 137(8): 579-95. https://dx.doi.org/10.1042/CS20220300.

- Gratacós E., Antolin E., Lewi L., Martínez J.M., Hernandez‐Andrade E., Acosta‐Rojas R. et al. Monochorionic twins with selective intrauterine growth restriction and intermittent absent or reversed end‐diastolic flow (Type III): feasibility and perinatal outcome of fetoscopic placental laser coagulation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008; 31(6): 669-75. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.5362.

- Peeva G., Bower S., Orosz L., Chaveeva P., Akolekar R., Nicolaides K.H. Endoscopic placental laser coagulation in monochorionic diamniotic twins with Type II selective fetal growth restriction. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2015; 38(2): 86-93. https://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000374109.

- Colmant C., Lapillonne A., Stirnemann J., Belaroussi I., Leroy‐Terquem E., Kermovant‐Duchemin E. et al. Impact of different prenatal management strategies in short‐ and long‐term outcomes in monochorionic twin pregnancies with selective intrauterine growth restriction and abnormal flow velocity waveforms in the umbilical artery Doppler: a retrospective obse. BJOG. 2021; 128(2): 401-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16318.

- Khalil A., Beune I., Hecher K., Wynia K., Ganzevoort W., Reed K. et al. Consensus definition and essential reporting parameters of selective fetal growth restriction in twin pregnancy: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019; 53(1): 47-54. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.19013.

- Monaghan C., Kalafat E., Binder J., Thilaganathan B., Khalil A. Prediction of adverse pregnancy outcome in monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy complicated by selective fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019; 53(2): 200-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.19078.

- Curado J., Sileo F., Bhide A., Thilaganathan B., Khalil A. Early‐ and late‐onset selective fetal growth restriction in monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy: natural history and diagnostic criteria. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 55(5): 661-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.20849.

- Kajiwara K., Ozawa K., Wada S., Samura O. Molecular mechanisms underlying twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Cells. 2022; 11(20): 3268. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/cells11203268.

- Satorres E., Martínez-Varea A., Diago-Almela V. sFlt-1/PlGF ratio as a predictor of pregnancy outcomes in twin pregnancies: a systematic review. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2023; 36(2): 2230514. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2023.2230514.

- D’Antonio F., Khalil A., Pagani G., Papageorghiou A.T., Bhide A., Thilaganathan B. Crown–rump length discordance and adverse perinatal outcome in twin pregnancies: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2014; 44(2): 138-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.13335.

- Litwinska E., Syngelaki A., Cimpoca B., Sapantzoglou I., Nicolaides K.H. Intertwin discordance in fetal size at 11–13 weeks’ gestation and pregnancy outcome. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 55(2): 189-97. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.21923.

Received 16.12.2024

Accepted 27.12.2024

About the Authors

Kristina A. Gladkova, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Fetal Medicine Unit, Institute of Obstetrics, Head of the 1st Obstetric Department of Pregnancy Pathology,V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, +7(916)321-10-07, k_gladkova@oparina4.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8131-4682

Ekaterina R. Frolova, PhD student at the 1st Obstetric Department of Pregnancy Pathology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, +7(495)438-07-88, e_frolova@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2817-3504

Viktoriya A. Sakalo, PhD, Junior Researcher at the Department of Pregnancy Pathology, Institute of Obstetrics, obstetrician-gynecologist at the 1st Obstetric Department of Pregnancy Pathology, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, +7(929)588-72-08, v_sakalo@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5870-4655

Kirill V. Kostyukov, Dr. Med. Sci, Head of the Department of the Ultrasound and Functional Diagnosis, V.I. Kulakov NMRC for OG&P, Ministry of Health of Russia,

117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparin str., 4, +7(495)438-25-29, k_kostyukov@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3094-4013