Evaluation of anxiety and associated factors in pregnant women

Background. Pregnancy is a critical life experience for women, which in many cases is featured with anxiety.Mazúchová L., Kelčíková S., Maskalová E., Dubovická Z., Malinovská N.

Objective. The aim of the study was to investigate anxiety-related symptoms in pregnant women and associated factors.

Materials and methods. The research was designed as a cross-sectional study. The research sample consisted of 304 pregnant women with physiological pregnancy and the average age was 27±4.95 years. The standardized Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was used to measure the symptoms of anxiety in pregnant women. The questionnaire was supplemented by the research variables (age, parity, trimester, satisfaction with partner support, health problems) essential for the research set characteristics as well as for the evaluation of the links between these items and anxiety. The received data were analysed using descriptive statistics, the Kruskal Wallis test and the Wilcoxon two-sample test.

Results. Evaluation of the BAI showed that most respondents (50.66%) had just mild symptoms of anxiety, 26.97% displayed moderate symptoms of anxiety, 10.53% presented severe symptoms of anxiety and 11.84% had no anxiety at all. Age and trimester of pregnancy were found to have no statistically significant effects on anxiety-related symptoms in pregnant women. Parity, satisfaction with partner support and health problems were shown to be statistically significant in relation to anxiety in pregnant women.

Conclusion. The incidence of anxiety disorder requires not only early diagnosis in primary health care settings but also timely measures that are to be taken by midwives and partners of pregnant women in order to prevent anxiety during pregnancy with an emphasis on the prevention of adverse consequences for the mother and child.

Keywords

Pregnancy is a period of intense physical and mental demands on pregnant woman’s body and well-being, and brings up a complex mix of emotions – on the one hand, joy and anticipation of what is to come, but on the other, fear and anxiety about the unknown [1]. Generally, anxiety is a frequent problem for pregnant women [2]. Pregnancy has been reported as a particularly vulnerable time for the onset or relapse of anxiety disorders in women [3]. According to Madhavanprabhakaran et al. [4], research studies on anxiety disorders in pregnancy in several parts of the world revealed high and diverse levels of prevalence of anxiety disorders from 14.00% to 54.00%.

Anxiety is characterised as a feeling of uncertainty and powerlessness. The adverse, long-term, stable, and sometimes even irreparable effects of anxiety during pregnancy can change pregnancy into an agonizing and unpleasant event of women’s life period. Pregnancy brings a variety of physiological and psychosocial changes [5]. The unbalanced phase leads to a feeling of anxiety. A pregnant woman’s emotions depend on her temperament and the surrounding environment. The very early concerns may include uncertainty about how the partner will respond to pregnancy and how this will affect their partnership and sexuality. Furthermore, a pregnant woman may face very different fears associated with pregnancy progression, anxiety about the child, lack of information on pregnancy and childbirth delivery itself or previous experience with pregnancy and giving birth. Anxiety in pregnancy can negatively impact on maternal mental health and the birth outcome. At the same time, it is regarded as a risk factor for postpartum depression. An anxiety reaction involves feelings of tightness, disquiet and internal tension. These feelings are accompanied by a physiological reaction affecting several functional systems and organs of an individual. There is an evidence that anxiety in pregnancy affects not only the woman’s health but its symptoms can also have detrimental effects on neurodevelopmental, cognitive and behavioural child outcomes [6, 7] bonding/ attachment quality and there may be an increased risk of premature birth, extended pregnancy, caesarean section or infant low birth weight [8, 9]. The emergent evidence highlights the need for early identification of maternal anxiety across the perinatal period and the provision of effective prevention [2].

Given the prevalence of antenatal anxiety and its consistent associations with adverse pregnancy and childbirth outcomes, the early detection and management of anxiety are highly essential [10, 11]. Healthcare professionals have the potential to identify and reduce anxiety as well as give emotional support [12].

The aim of the study was to investigate anxiety-related symptoms in pregnant women and the associated factors.

Materials and methods

The research was designed as a cross-sectional study.

The research sample consisted of 304 pregnant women that fulfilled the following inclusive criteria: a woman with physiological pregnancy, willing to cooperate, and having signed the written informed consent for participation in the research study.

The research sample was obtained by convenient sampling method. The research was conducted in three gynaecological outpatient clinics of the Žilina Region, Slovakia. The choice of the outpatient clinics was determined by their availability and also by the obtained consent of their gynaecologists. Pregnant women were contacted personally during their prenatal counselling at the outpatient clinics. The clarity of the questionnaire was verified by a pilot study with 5 respondents. Based on the piloting, the problematic formulations of a formal and stylistic character were modified. A combined method of questionnaire administration was chosen. Pregnant women, visiting the prenatal counselling, were personally addressed by the trained nurses, who had been instructed by the research team on the study, data collection method and study inclusion criteria as well as on completing the questionnaire. Those pregnant women who agreed to participate in the research project signed the informed consent and subsequently received a link to an online questionnaire via email. The questionnaire could be completed in either print or electronic form. A total of 340 questionnaires were distributed: 80 were given out personally in the gynaecological outpatient clinics and had a response rate of 87.50% (70 questionnaires); 260 questionnaires were sent electronically to e-mail addresses and had a response rate of 95.38% (248 questionnaires). The total response rate was 93.53%. Out of a total of 318 completed questionnaires, 14 questionnaires were excluded due to incorrect or incomplete answers or due to their non-compliance with the inclusion criteria. As a result, a total of 304 questionnaires were used for the study research.

In order to collect the relevant data, the standardized Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [13], was used to measure the symptoms of anxiety in pregnant women. The BAI consists of 21 self-reported items related to the intensity perception of vegetative symptoms, cognitive and emotional manifestations. The 4-point Likert scale was chosen to record and measure the responses. Anxiety-related symptoms were assessed by the BAI as follows: 0–5 points, did not have any anxiety at all; 6–15 points, mild symptoms of anxiety; 16–25 points, moderate symptoms of anxiety; more than 26 points, serious symptoms of anxiety. The final value, measured by counting the particular answers, oscillated in the range from 0 to 63. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha reliability) coefficient of the BAI in our research was 0.65.

The questionnaire was supplemented by the research variables (age, parity, trimester, satisfaction with partner support, health problems during pregnancy), essential for the research set characteristics as well as for the evaluation of the links between these items and the symptoms of anxiety during pregnancy.

The study was approved by the Ethical Commission of the Žilina (Number EC: 05404/2016/OZ-03) Self-Governing Regions (Slovak Republic). All participants received full information about the nature and goals of the research, as well as about the details connected with their involvement in the study. The data collection was anonymous, and all participants expressed their willingness to be included in the study, attaching their informed consent.

Statistical analysis

The received data were analysed using descriptive statistics. The data on the total score for factors (age, trimester, parity, partner support satisfaction, health problems) were visualized by swarm plot, overlaid with boxplot.

The normality of the total score for the levels of a factor was assessed by the Quantile-Quantile plot, with the 95% confidence band constructed by bootstrap. Since the distribution of the total score for the levels of all the considered factors was not gaussian, the data were subjected to nonparametric tests: either the Kruskal– Wallis test for a factor with more than two levels, or the Wilcoxon two sample test for the factors with two levels. A test result with a p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Results

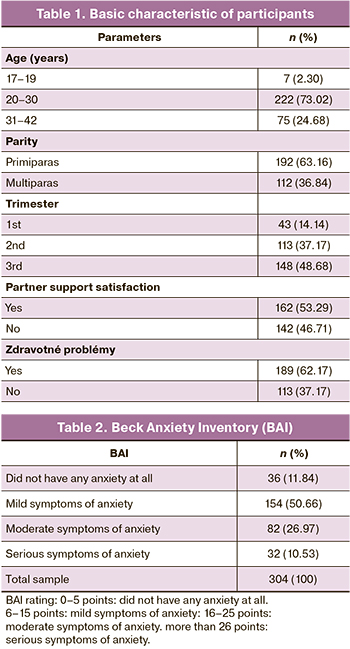

Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of participants.

The average age of the respondents was 27 years ± 4.95 (range 17–42 years). The majority of women were aged 20–30 years (73.02%), then 31–43 years (24.68%) and the least (2.30%) were women aged 17–19 years.

In terms of parity, the research group consisted of 63.16% of primiparas and 36.84% of multiparas.

The majority of women (48.68%) were in the third trimester of pregnancy, 37.17% in the second trimester and 14.14% in the first trimester of pregnancy.

As many as 53.29% of the women were satisfied with partner support, while 46.71% were dissatisfied.

Health problems during pregnancy were reported by 37.17% of women. Among the most common complications were listed nausea and emesis gravidarum (69. 91%) as well as other problems such as: fatigue, dizziness, leg swelling, back pain, shortness of breath, cramps in the calves, anaemia and excessive weight gain.

Table 2 presents the symptoms of anxiety in pregnant women.

Based on evaluation of the BAI, most respondents (50.66%) showed just mild symptoms of anxiety, 26.97% displayed moderate symptoms of anxiety, 10.53% demonstrated serious symptoms of anxiety and 11.84% did not have any anxiety at all.

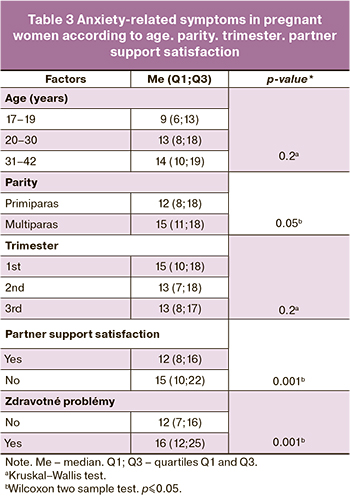

Table 3 presents the relationship between the examined factors (age, parity, trimester, satisfaction with partner support, health problems) and anxiety-related symptoms in pregnant women.

Table 3 presents the relationship between the examined factors (age, parity, trimester, satisfaction with partner support, health problems) and anxiety-related symptoms in pregnant women.

The average score on the anxiety scale showed better results for women aged 17–19 years than for women aged 20–30 years, while the worst outcomes were linked with women aged 31–43 years. Using the Kruskal Wallis test between the groups defined by the age, the differences in anxiety-related symptoms were not statistically significant (p=0.2).

The average score on the anxiety scale showed the better results for the primiparas and worse for the multiparas. Using the Wilcoxon two sample test between the groups defined by the parity, the differences in anxiety-related symptoms were statistically significant (p=0.05).

The average score on the anxiety scale showed better results for the women in their third trimester, then in the second trimester and the worst in the first trimester of pregnancy. Using the Kruskal Wallis test between the groups defined by the trimester of pregnancy, the differences in anxiety-related symptoms were not statistically significant (p=0.2).

The average score on the anxiety scale showed better results for the women being satisfied with partner support, and worse for those being dissatisfied in this area. Using the Wilcoxon two sample test between the groups defined by satisfaction with partner support, statistically significant differences in the manifestation of anxiety-related symptoms were found (p=0.001).

The average score on the anxiety scale showed better results for the women, who had not had any health problems and worse for the women, who had had health problems during pregnancy. Using the Wilcoxon two sample test between the groups defined by health problems, statistically significant differences in the manifestation of anxiety-related symptoms were found (p=0.001).

Discussion

Given the importance of mental health in pregnancy for both woman and her fetus, we focused on examining the manifestation of anxiety and its related factors with an emphasis on early prevention. Based on evaluation of the BAI, most respondents (50.66%) showed just mild symptoms of anxiety, 26.97% displayed a moderate symptoms of anxiety, and 10.53% demonstrated serious symptoms of anxiety, which is comparable to other studies [4, 14]. As part of preventing anxiety during pregnancy, pregnant women need a person to provide them with psychological support, answer their questions and dispel their concerns. Primary care professionals providing perinatal care for women, such as doctors, midwives / nurses but also mental health professionals, should provide adequate support to pregnant women experiencing psychological problems in order to achieve improvement for both mothers and children [15]. The suitable and sound explanation of all changes that occur during pregnancy, considerate behaviour, patient and tactful approach are all cornerstones of successful perinatal care. Effective psychophysical training can also play an important role in this context.

Our study investigated differences in anxiety based on age variable. The average score on the anxiety scale showed better results for women aged 17–19 years than for women aged 20–30 years, while the worst outcomes were linked with women aged 31–43 years. Our results concerning the links between the higher age and anxiety during pregnancy appear consistent with the findings in other study [16]. Women over the age of 30 may be at risk for anxiety as the evidence suggests that older mothers are much more likely than younger mothers to experience a variety of frequent complications during pregnancy [17] and these may be the sources of their concern and fear. In our study, comparing the analysis of variance between the groups defined by the age, the differences in anxiety-related symptoms were not statistically significant. Similarly, several other studies [18, 19] have also confirmed no effect of age on anxiety in pregnancy. However, some other studies have associated mother’s younger age to anxiety in pregnancy [3, 20]. Adolescent mothers can be at risk since they have neither experience and knowledge of the course of pregnancy and childbirth, nor knowledge of newborn care. The absence of a significant relationship in our study could be attributed to a small sample of younger-aged female participants included in the research.

We also examined the differences in anxiety based on parity variable, which was found to be statistically significant. The average score on the anxiety scale showed the best results for the primiparas and worse for the multiparas. It is obvious that primiparas may experience stronger emotional changes and more intense unrecognized and new feelings, which can lead to various uncertainties and fears. Multiparas may experience concerns due to problematic previous pregnancies and childbirth, negative childbirth experiences as well as other psychosocial or economic problems. Alipour et al. [21] also reported on a greater risk of prenatal anxiety for multiparas whereas other study [22] concluded that primiparas had experienced more anxiety than multiparas. However, some other studies [23, 24] proved no significant relationship between parity and anxiety in pregnancy. We can agree with the findings of Biaggi et al. [5], suggesting that the role of parity in increasing the risk of developing an anxiety disorder is not clear.

The third area analysed in our research was trimester of pregnancy. The average score on the anxiety scale showed the better results for women in their third trimester, then in the second trimester and worst in the first trimester of pregnancy. These results are consistent with the findings in several other studies [19, 25]. Some studies [2, 26] proved the highest prevalence of anxiety in the third trimester of pregnancy. In contrast to the above stated, our score revealed that the average anxiety levels were the worst in the first trimester. At the beginning of pregnancy, a woman must adapt to pregnancy and to the physical and emotional changes in the body and around her, including physical symptoms such as morning sickness, vomiting – which is closely related to anxiety, and many other pregnancy-related symptoms. Various researches reported on the association between anxiety disorder development and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy [27]. Other study [28] also confirmed that anxiety occurs more frequently during the first and the third trimester of pregnancy, probably because women are most vulnerable at this time. They are more likely to experience stress when facing a new situation of becoming mother, and then when they are about to deliver their baby and start a new life. Women’s concerns in the second trimester may be related to the fact that most prenatal examinations and screenings take place during this period. Comparing the analysis of variance between the groups defined by the trimester of pregnancy, the differences in anxiety-related symptoms were not statistically significant. When evaluating perception of pregnancy, the respondents did not evaluate it in relation to trimesters, but in general, which could have affected the results. Further, when comparing the anxiety experience according to trimesters, it would have been more credible if we had conducted a prospective study, which would have compared the same sample of women in different periods of pregnancy.

Perceived social support seems to be a protective factor against anxiety disorders in pregnant women, showing a positive effect on mental health [29]. Social support, with partner involvement, is also an important correlate of maternal well-being during pregnancy and perinatal outcomes [30]. The statistical significance was demonstrated in assessment of anxiety in conjunction with satisfaction with partner support. Partner-related factors in relation to anxiety have been considered significant in a number of other studies [5, 10, 30] Pregnant women lacking the support of their partner or other close person show high levels of prenatal anxiety and depression [25]. The area of satisfaction with partner support cannot be directly influenced by midwives, but it is important to motivate partners to participate in psychophysical preparation for childbirth during prenatal care. Attaining such preparation can help the partner to get informed not only about pregnancy, childbirth and childcare, but also about the partner’s important role in supporting a woman and her mental health.

Statistical significance has also been demonstrated in the assessment of anxiety related to health problems during pregnancy. The women who reported some health problems during pregnancy were found to have higher anxiety scores. Nausea and vomiting were the most frequently reported health problems. Several studies have found a correlation between anxiety and nausea, and vomiting during pregnancy [31, 32]. A variety of poor outcomes are associated with anxiety during pregnancy: preeclampsia, increased nausea and vomiting, spontaneous preterm labour, preterm delivery, a more difficult labour and delivery with increase of PTSD symptoms related to birth, elective caesarean section [33]. High levels of anxiety during pregnancy have an adverse effect not only on the mother, childbirth but also on the child [34]. Anxiety in early pregnancy can lead to foetal loss and in the second and third trimesters to weight loss, emotional problems, hyperactivity, cognitive impairment in children [35]. Screening and prevention of anxiety in prenatal care can effectively prevent these serious risks.

Limitations of the study

These results and findings should be seen in the light of the research limitations. Limitation of the study is the convenience sample, which allows the conclusions to be interpreted and generalized only to the selected research sample. Further study limitations can be seen in the uneven distribution of the file when comparing anxiety by age, parity, and the period of pregnancy, which could have greatly distorted the results. Other factors (e.g. education, financial status and situation, personality traits, personal history of mental illness, unplanned or unwanted pregnancy, domestic violence, and pregnancy loss) may have played a more important role in evaluating anxiety than those which we have examined. We can consider our study as partial, but despite the mentioned limitations we believe that the study has brought compelling results.

Conclusion

Cases of anxiety require early diagnosis and intervention health professionals (gynaecologist, midwife) in primary health care settings as well as timely measures for the prevention and alleviation of anxiety during pregnancy. It would be desirable to implement screening procedures for timely identification and diagnosis of anxiety in pregnancy during the prenatal checks, monitoring the risks for pregnant women. On the part of health professionals, it is necessary to provide correct information, conducting psychological interventions such as expressing interest in pregnant women, building confidence in relationships, open communication, acceptance of the pregnant women, empathy, support and respect, as well as cooperation with a partner. This is important with an emphasis on preventing adverse consequences for the mother and child. We believe that our study has arrived to the findings that could help to improve the quality of primary prenatal care for pregnant women.

References

- Huizink A., Menting B., De Moor M., Verhage M.L., Kunseler F.C., Huizink A.C., Menting B., De Moor M.H.M., Verhage M.L., Kunseler F.C., Schuengel C. et al. From prenatal anxiety to parenting stress: a longitudinal study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2017; 20(5): 663-72. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00737-017-0746-5.

- Dennis C.L., Falah-Hassani K., Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2017; 210(5): 315-23. https://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179.

- Martini J., Petzoldt J., Einsle F., Beesdo-Baum K., Höfler M., Wittchen H.U. Risk factors and course patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders during pregnancy and after delivery: a prospective-longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2015; 175: 385-95. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.012.

- Madhavanprabhakaran G.K., D’Souza M.S., Nairy K.S. Prevalence of pregnancy anxiety and associated factors. IJANS. 2015; 3: 1-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2015.06.002.

- Biaggi A., Conroy S., Pawlby S., Pariante C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016; 191: 62-77. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014.

- Sinesi A., Maxwell M., O'Carroll R., Cheyne H. Anxiety scales used in pregnancy: systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2019; 5(1): e5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.75.

- Перова Е.И., Стеняева Н.Н., Аполихина И.А. Беременность на фоне тревожно-депрессивных состояний. Акушерство и гинекология. 2013; 7: 14-7. [Perova E.I., Stenyaeva N.N., Apolikhina I.A. Pregnancy in the presence of anxiety and depressive conditions. Akusherstvo i ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013; 7: 14-7. (in Russian)].

- Nath S., Ryan E.G., Trevillion K., Bick D., Demilew J., Milgrom J. et al. Prevalence and identification of anxiety disorders in pregnancy: the diagnostic accuracy of the two-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2). BMJ Open. 2018; 8(9): e023766. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023766.

- Zhong Q.Y., Gelaye B., Zaslavsky A.M., Fann J.R., Rondon M.B., Sáncher S.E. et al. Diagnostic validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder -7 (GAD-7) among pregnant women. PLoS One. 2015; 10(4): e0125096. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125096.

- Bayrampour H., Vinturache A., Hetherington E., Lorenzetti D.L., Tough S. Risk factors for antenatal anxiety: a systematic review of the literature. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2018; 36(5): 476‐503. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2018.1492097.

- Mazúchová L. Preventive programmes of CAN syndrome in children. Kontakt. 2012; 14(3): 269-75.

- Hore B., Smith D.M., Wittkowski A. Women’s experiences of anxiety during pregnancy: an interpre¬tative phenomenological analysis. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2019; 2(1): 1026.

- Beck A.T., Epstein N., Brown G., Steer R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988; 56(6): 893‐7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893.

- Rubertsson C., Hellström J., Cross M., Sydsjö G. Anxiety in early pregnancy: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2014; 17(3): 221-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0409-0.

- Staneva A., Bogossian F., Pritchard M., Wittkowski A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2015; 28(3): 179-93. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.02.003.

- Nasreen H.E., Kabir Z.N., Forsell Y., Edhborg M. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy: a population based study in rural Bangladesh. BMC Womens Health. 2011; 11: 22. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-11-22.

- Zapata-Masias Y., Marqueta B., Gómez Roig M.D., Gonzalez-Bosquet E. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in women ≥40years of age: associations with fetal growth disorders. Early Hum. Dev. 2016; 100: 17-20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.04.010.

- Kang Y.T., Yao Y., Dou J., Guo X., Li S.Y., Zhao C.N. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of maternal anxiety in late pregnancy in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016; 13(5): 468. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13050468.

- Soto-Balbuena C., Rodríguez M.F., Escudero Gomis A.I., Ferrer Barriendos F.J., Le H.N., Pmb-Huca G. Incidence, prevalence and risk factors related to anxiety symptoms during pregnancy. Psicothema. 2018; 30(3): 257-63. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.7334/psicothema2017.379.

- Kannenberg K., Weichert J., Rody A., Banz-Jansen C. Treatment-associated anxiety among pregnant women and their partners: what is the influence of sex, parity, age and education? Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016; 76(7): 809-13. https://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-101546.

- Alipour Z., Lamyian M., Hajizadeh E. Anxiety and fear of childbirth as predictors of postnatal depression in nulliparous women. Women Birth. 2012; 25(3):e37-43. https://dx.doi.org/0.1016/j.wombi.2011.09.002.

- Türk R., Erkaya R. Determining the status of anxiety and depression in women during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.CBU International Conference Proceedings. 2018; 6: 971-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.12955/cbup.v6.1280.

- Nath A., Venkatesh S., Balan S., Metgud C.S., Krishna M., Murthy G.V.S. The prevalence and determinants of pregnancy-related anxiety amongst pregnant women at less than 24 weeks of pregnancy in Bangalore, Southern India. Int. J. Womens Health. 2019; 11: 241‐8. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S193306.

- Fairbrother N., Young A.H., Zhang A., Janssen P., Antony M.M. The prevalence and incidence of perinatal anxiety disorders among women experiencing a medically complicated pregnancy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2017; 20(2): 311-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0704-7.

- Branecka-Woźniak D., Karakiewicz B., Torbè A., Ciepiela P., Mroczek B., Stanisz M. et al. Evaluation of the occurrence of anxiety in pregnant women with regard to environmental conditions. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2018; 20(4): 320-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.5114/fmpcr.2018.79341.

- Silva M.M.J., Nogueira D.A., Clapis M.J., Leite E.P.R.C. Anxiety in pregnancy: prevalence and associated factors. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. 2017; 51: e03253. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1980-220X2016048003253.

- Beyazit F., Sahin B. Effect of nausea and vomiting on anxiety and depression levels in early pregnancy. Eurasian J. Med. 2018; 50(2): 111‐5. https://dx.doi.org/10.5152/eurasianjmed.2018.170320.

- Yanikkerem E., Ay S., Mutlu S., Goker A. Antenatal depression: prevalence and risk factors in a hospital based Turkish sample. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2013; 63(4): 472-7.

- Peter P.J., de Mola C.L., de Matos M.B., Coelho F.M., Pinheiro K.A., da Silva R.A. et al. Association between perceived social support and anxiety in pregnant adolescents. Braz. J. Psychiatry. 2017; 39(1): 21-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1806.

- Cheng E.R., Rifas-Shiman S.L., Perkins M.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Gillman M.W., Wright R. et al. The influence of antenatal partner support on pregnancy outcomes. J. Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016; 25(7): 672‐9. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/jwh.2015.5462.

- Simşek Y., Celik O., Yılmaz E., Karaer A., Yıldırım E., Yoloğlu S. Assessment of anxiety and depression levels of pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum in a case-control study. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2012; 13(1): 32-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.5152/jtgga.2012.01.

- Anniverno R., Bramante A., Mencacci C., Durbano F. Anxiety disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. In: Durbano F., ed. New insights into anxiety disorders. Croatia: InTech Open; 2013: ch.11: 260-85. https://dx.doi.org/10.5772/46003.

- Ding X.X., Wu Y.L., Xu S.J., Zhu R.P., Jia X.M., Zhang S.F. et al. Maternal anxiety during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2014; 159: 103-10. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.027.

- Shahhosseini Z., Pourasghar M., Khalilian A., Salehi F. A review of the effects of anxiety during pregnancy on children's health. Mater. Sociomed. 2015; 27(3): 200-2. https://dx.doi.org/10.5455/msm.2015.27.200-202.Поступила 09.10.2020

Received 09.10.2020

Accepted 12.01.2021

About the Authors

Lucia Mazúchová, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing and Midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery. E-mail: mazuchova@jfmed.uniba.sk. ORCID: 0000-0001-9363-0922. Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.Simona Kelčíková, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing, Midwifery and Public health at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine

in Martin, Department of Midwifery. E-mail: kelcikova@jfmed.uniba.sk.ORCID: 0000-0002-2347-4343. Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.

Erika Maskalová, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing and Midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery. Tel.: 00421 432633430. E-mail: maskalova@jfmed.uniba.sk. ORCID: 0000-0003-2806-4586. Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.

Zuzana Dubovická, BMid is a student of midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery.

E-mail: zuzana.dubovicka788@gmail.com. Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.

Nora Malinovská (Corresponding Author), MA, PhD, a lecturer in Medical Latin and English for Medical Purposes at Comenius University (Bratislava),

Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Foreign Languages. Tel.: 00421 432633520. E-mail: malinovska@jfmed.uniba.sk.

ORCID: 0000-0001-5334-207X. Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.

For citation: Mazúchová L., Kelčíková S., Maskalová E., Dubovická Z., Malinovská N. Evaluation of anxiety and associated factors in pregnant women.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/ Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021; 3: 66-72 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.3.66-72