Clinical and diagnostic features of different forms of genital endometriosis in female adolescents

Endometriosis is a condition that can be misdiagnosed on average for 8–10 years. This is especially true for adolescent patients, who are waiting for healthcare 2–3 times longer than adult women. Objective: To study clinical and diagnostic features of different forms of genital endometriosis in female adolescents. Materials and methods: The case-control study included adolescents aged 13–18 years. The main group included 98 girls with confirmed laparoscopic diagnosis of endometriosis; the comparison group consisted of 44 somatically healthy girls. Results: The patients with endometriosis were characterized by the burden of inherited gynecologic diseases via close relatives compared to healthy girls (32.7% versus 9.1%, p<0.001), earlier menarche (11.8±2.5 versus 12.5±1.2, р<0.001), heavy (32.1% versus 10.4%, р=0.034) and irregular menstrual bleeding at menarche (42.9% versus 15.9%, р=0.002). The patients with endometriosis had lower abdominal pain in the first 3–4 days of menstruation, which scored 8–9 points on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) (75.3% versus 13.6%, p<.001), higher levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) (8.3±6.7 versus 4.1±1.9, р<0.001), estradiol (335.2±292.3 versus 171.5±73.9, р=0.032), prolactin (481.2±312.4 versus 237.8±126.4, р<0.001), 17-OHР (5.8±3.7 versus 3.9±1.8, р=0.022), total androstenedione (10.8±4.3 versus 8.4±2.5, р=0.014). According to pelvic MRI, the signs of genital endometriosis were detected in 37 (78.7%) patients with external genital endometriosis and in 24 (88.9%) patients with adenomyosis. Conclusion: In 96.9% of cases, in adolescents with persistent dysmenorrhea scoring 8–9 points according to VAS, the diagnosis of genital endometriosis was confirmed laparoscopically. The significant factors for the diagnosis were the burden of inherited endometriosis (χ2=82.8, p<0.001), persistent dysmenorrhea at menarche (χ2=49.8, p<0.001), suspected genital endometriosis according to MRI results (χ2=91.4, p<0.001), high levels of LH (χ2=28.5, p<0.001) and androstenedione (χ2=8.0, p<0.005).Khaschenko E.P., Allakhverideva E.Z., Uvarova E.V., Chuprynin V.D., Kylabukhova E.A., Luzhina I.A., Uchevatkina P.V., Mamedova F.Sh., Asaturova A.V., Tregubova A.V., Magnaeva A.S.

Keywords

According to different authors, endometriosis occurs in 10–16% of women of early reproductive age, and its clinical manifestations are chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea and future infertility [1, 2]. The exact prevalence of endometriosis in adolescents is unknown. However, at least in two thirds of girls with chronic pelvic pain, which is resistant to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or combined oral contraceptives (COCs), pelvic endometriosis is identified during diagnostic laparoscopy [2]. Currently, severe forms of widespread endometriosis occur in patients of younger age, and significantly worsen quality of life in patients and often require repeated serious surgical interventions, including in early reproductive age. The prevalence of endometriosis among adolescents was estimated in the systematic review by Janssen E. et al. based on 15 studies, which were carried out from 1980 to 2011, and included 880 female adolescents with dysmenorrhea or pelvic pain. Endometriosis was confirmed laparoscopically in 62% of cases [3].

Due to increasing prevalence and progressive nature of the disease, early diagnosis is especially important. On average, it takes 5-10 years from the onset of the first symptoms to making the diagnosis. At the same time, female adolescents are waiting for healthcare 3 times longer than adult women (6.0±0.2 versus 2.0±0.3 лет, p<0.0001) [1, 2, 4]. It is difficult to diagnose endometriosis in adolescents due to non-specific clinical picture, the lack of non-invasive tests, and difficulty in detecting the initial forms of the disease using instrumental methods. Ballweg M. et al. analyzed the data of patients with endometriosis in early reproductive age. They concluded that delay in diagnosis is mainly due to the fact that the doctors are not ready to make diagnosis of endometriosis at yearly age; and before the correct diagnosis was made, the patients underwent examination by 4 or even more doctors [5]. Inflammatory, neuroendocrine, chronic comorbid conditions, which are also often present in adolescent patients, further complicate the diagnosis [6].

Endometriosis in adult women is mainly characterized by cyclic pelvic pain. However, pelvic pain in girls can be both cyclic and acyclic [5]. In early reproductive age, along with classical symptoms such as dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, atypical symptoms of endometriosis are often observed, namely, vague abdominal symptoms, gastrointestinal disorders and urogenital symptoms. It was demonstrated that only 9.4% of adolescents experienced the classical symptoms of cyclic pain [5, 7].

It is known that the stage of the disease does not clearly correlate with the presence or severity of the symptoms, and none of the symptoms is specific for endometriosis [8, 9]. Pelvic pain in patients with endometriosis can be cramping or aching. It usually occurs 1–2 days before the period starts and lasts for the first 3–4 days of menstrual bleeding and may continue for several days after menstruation [10]. Common symptoms of endometriosis in young women also include chronic pelvic pain, which, unlike dysmenorrhea, lasts for 6 months or longer and may be persistent, intermittent, cyclic, or acyclic. Moreover, in the presence of endometriosis, the symptoms, such as such as bowel and bladder dysfunction, abnormal uterine bleeding, heavy menstrual bleeding, lower back pain, chronic fatigue syndrome, headache, dizziness may occur. Gastrointestinal symptoms may include abdominal bloating, constipation, diarrhea, nausea, and pain during or after bowel movements. Urinary dysfunction may include dysuria, hematuria, and diffused low back pain [11].

Many studies assessed the diagnostic value of biomarkers for endometriosis. However, currently there are no reliable recommendations for the parameters of endometrial tissue, menstrual or сervical fluids and immunological parameters to be used for diagnostic testing of endometriosis [12]. Given the chronic character of the disease and significant impact on reproductive function, ovarian reserve, social and psychological status, and young patients’ quality of life, the major objective at present is to detect the disease as early as possible and timely start pathogenetic therapy.

The objective of the study was to investigate clinical and diagnostic features of different forms of genital endometriosis in female adolescents.

Materials and methods

The case-control study was carried out in the 2nd Gynecological Department (for children and adolescents), the National Μedical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of the Ministry of Health of Russia (the Center). The main group included 98 girls with confirmed laparoscopic diagnosis of genital endometriosis, who were followed-up from 2016 to 2022. The comparison group consisted of 44 somatically healthy girls of the same age, who had regular menstrual cycles and had no gynecologic or endocrine pathology. The study was approved by Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the Center. Informed consent was obtained from the patients and their legal representatives to include the patients in the study, use their personal data and publish the obtained results.

Inclusion criteria in the main group were: the age of patients from menarche to 18 years; clinical symptoms and complains of persistent dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain resistant to NSAIDs and antispasmodic drugs; confirmed diagnosis of different forms of genital endometrisosis according to ultrasound (US) results, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and laparoscopic images; not taking drugs including COCs for the last 3 months prior to the start of the study; patients’ informed consent for inclusion in the study.

General exclusion criteria were: the age of patients over 18 years; somatic, endocrine pathology, oncologic diseases, infectious diseases; absence of dysmenorrhea and/or chronic pelvic pain (for the main group); malformations of genital organs associated with impaired flow of menstrual blood; lack of informed consent.

The main group was divided into 3 subgroups depending on the form of genital endometriosis: subgroup 1 consisted of the girls with external genital endometriosis (EGE) within abdomen (n=65); subgroup 2 included the girls with adenomyosis (ADM) (n=15); subgroup 3 consisted of the girls with endometrial cysts (EC) (n=18).

The research methods included the analysis of extended clinical and instrumental tests:

- clinical and anamnestic data: complains, maternal medical history of pregnancy and childbirth, hereditary burden, the clinical picture of the disease;

- clinical laboratory test data: full blood count; biochemical blood test: the levels of total protein, glucose, urea, creatinine, total and direct bilirubin, C-reactive protein; hormonal blood profile on the 2nd–4th day of the menstrual cycle: thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin, estradiol, testosterone, cortisol, anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), tumor markers CA-125, CA-19-9;

- the data of instrumental diagnostics: pelvic US on the 5th–7th day of the menstrual cycle and pelvic MRI prior to menstruation (from the 25th day of the menstrual cycle), the data of laparoscopic image (surgical diagnosis, the type, size and area of lesion);

- the data of histological examination of surgical specimens (macroscopic and microscopic description).

Statistical analysis

Statistical data processing was performed using Excel software (Microsoft) and Statistica 8 software (Statsoft Inc.). Frequency and percentage (%) for categorical variables were calculated. The differences were compared using contingency tables, χ² test, Fisher's exact test. The parametric Student's t-test was used to compare the mean values in the normal distribution of variables and homogeneity of variance of two independent samples. The differences were considered to be statistically significant at р<0.05. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess the differences between the groups in nonparametric distribution of quantitative variables of independent samples. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare variables in several independent groups with normal distribution. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for non-normal distribution. Pairwise multiple comparisons in the groups with a normal distribution were performed using post hoc multiple comparison test (Least Significant Difference (LSD)) and Dunn's Multiple Comparison Test for nonparametric distribution. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to check the correlations between the indicators in linear relationship. In nonparametric distribution, the Spearman rand Kendall rank correlation coefficients were used, when there were more than two variables. Risk factors were assessed using multivariate logistic regression analysis, calculation of adjusted odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI), as well as factorial ANOVA was used to analyze the effects of interaction between categorical independent factors.

Results

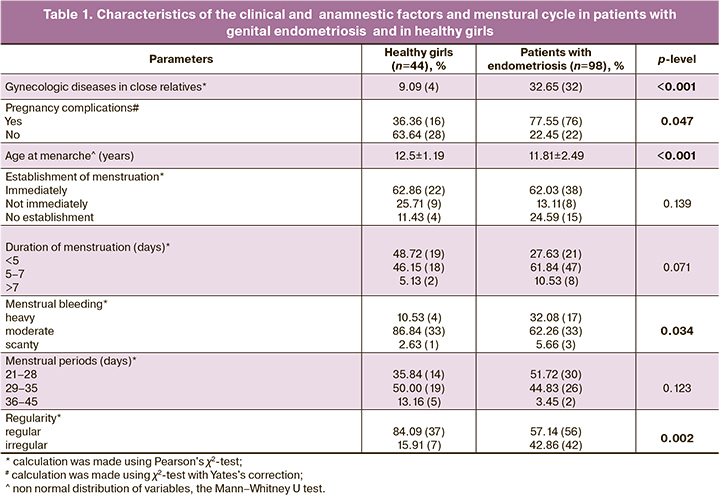

According to the clinical and anamnestic data, the patients in the main group had a burden of the disease inherited from relatives with endometriosis and other gynecological diseases (uterine fibroids, abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial hyperplasia) significantly more often compared to healthy girls (32/98 (32.7%) versus 4/44 (9.1%), р<0.001; χ2-test). Also, among the patients in the main group, pregnancy complications in their mothers (threatened miscarriage, toxicosis, preeclampsia) were significantly more often – 76/98 (77.6%) cases versus 16/44 (36.4%) in the group of healthy girls (р=0,047, χ2-test with Yates's correction). The data are shown in Table 1.

There was no significant difference in body mass index between the patients in the main and in the comparison groups (20.5±3.74 versus 20.3±5.8 kg/m2, р=0.54). In the main group, the major complaints were: expressed dysmenorrhea resistant to NSAIDs and antispasmodic drugs (73/98 (75.3%)). In the comparison group, the patients had no complaints of resistant severe dysmenorrhea (р<0.001, χ2-test). In the control group, functional dysmenorrhea in 6/44 (13.6%) girls did not require repeated intake of NSAIDs and scored 4–7 points on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) on the first day of menstruation. At the same time, pain was easily removed after a single dose of NSAID. The patients with endometriosis complained of pain up to 8–9 points (VAS) and discribed menstrual pain as a sharp pulsing sensation in the lower abdomen, which on average appeared the day before period bleeding started, and lasted for the first 3 days (40.8%); intermittent pain in the lower abdomen was not associated with the menstrual cycle (13.4%).

In girls with endometriosis the average age at menarche was lower (11.8±2.49 years) compared to healthy girls (12.5±1.19 years) on average by 8 months (р<0.001; t-test). Irregular menstruation in the main group was significantly more often compared to healthy girls – 42 (42.9%) versus 7 (15.9%) (р=0.002, χ2-test). In addition, the patients with endometriosis had heavy menstrual bleeding more often compared to the group of healthy girls – 17 (32.1%) versus 4 (10.5%) (р=0.034, χ2-test).

Multifactorial analysis of clinical and anamnestic picture confirmed that a significant risk factor for development of endometriosis in girls was a burden of the disease inherited from relatives with endometriosis and other gynecological diseases (OR 4.85, CI 1.58; 14.87, р=0.005) and painful periods since menarche (OR 19.30, CI=7.19; 51.60, р<0.001).

According to full blood count, a higher level of eosinophils was in patients with endometriosis versus healthy adolescents (2.6±2.15 versus 1.9±2.15, р=0.042, the Mann–Whitney U test).

Of particular interest were the levels of inflammatory markers, namely, comparison between the number of white blood cells (WBCs) in the group of patients with endometriosis and healthy girls (6.5±1.82 versus 6.9±2.36, р=0.392, the Mann-Whitney U test), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (3.4±2.15 versus 3.3±1.60, р=0.804, the Mann-Whitney U test), and between the levels of C-reactive protein (0.9±0.99 versus 1.0±0.91, р=0.393, the Mann–Whitney U test). However, the differences between these parameters were not statistically significant.

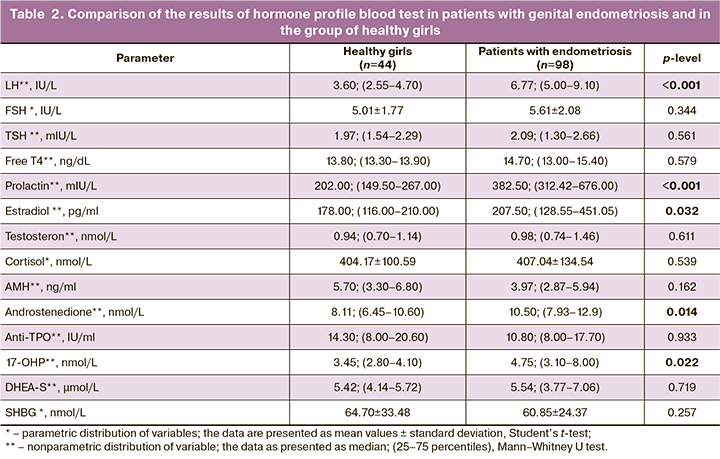

Analysis of hormonal profile showed that, there was no significant difference in most parameters between the groups except for high levels of LH in the main group compared to the control group (8.3±6.72 versus 4.1±1.96, р<0.001), estradiol (335.2±292.28 versus 171.5±73.95, р=0.032), 17-ОН progesterone (17-OHP) (5.8±3.63 versus 3.9±1.84, р=0.022), total androstenedione (10.8±4.27 versus 8.4±2.45, р=0.013) and prolactin (481.2±312.42 versus 237.8±126.43, р<0.001). The data are shown in Table 2.

Multifactorial analysis showed that elevated levels of LH (OR 0.09, CI=0.02; 0.37, р<0.001) and androstenedione (OR 1.23, CI=1.05; 1.42, р=0.01), as well as their combination (OR 0.09, CI= 0.02; 0.37, р<0.001) significantly increased the risk of endometriosis in girls.

The patients with endometriosis had higher levels of CA-125, but not exceeding the upper limit of normal level (35 U/L). Comparison with the control group did not show significant difference between the parameters of tumor markers CA-125 (31.4±55.80 versus 19.6±9.93, р=0.469), СА19-9 (10.01±9.49 versus 6.53±2.39, р=0.746), НЕ-4 (49.23±9.72 versus 50.21±2.31, р=0.889), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (1.14±1.61 versus 2.5±1.78, р=0.899)

Comparison of US measurements of endometrial thickness showed that it was significantly thicker in girls with endometriosis versus the control group (0.8±0.33 versus 0.5±0,32 cm, р<0.001), and could be due to local hyperestrogenism associated with endometriosis. The comparative analysis of sonographic parameters of the uterus showed that statistically significant difference was found in thickened uterine lining in patients with endometriosis compared to healthy girls (3.3±0.83 versus 2.9±0.51, р=0.001). Comparison of the ovarian length, thickness, width and volume showed no significant difference between the group of patients with endometriosis without EC and the group of healthy girls.

Further, comparison between the subgroups of patients with genital endometriosis was performed, and these subgroups were compared with the control group. The only anamnestic factor indicating dysmenorrhea related to menarche was significant for all the subgroups (EGE1 – 76.92%, ADM2 –66.67%, EC3 –76.47% versus 13.64% in the comparison group, р1,4<0.001, р2,4<0.001, р3,4<0.001, respectively). The patients with EGE had a burden of endometriosis inherited from relatives with gynecological diseases compared to healthy girls (38.46% versus 9.09%, р=0.001), heavier menstrual bleeding in girls (41.18% versus 10.53%, р=0.003) and irregular menstrual cycle (43.08% versus 15.91%, р=0.003), as well as significantly high levels of LH (9.1±7.39 versus 4.1±1.96, р<0,001), FSH (6.0 ±2.02 versus 5.0±1.77, р=0.028), 17-ОНP (6.1±3.68 versus 3.9±1.84, р=0.038) in peripherial blood. In the groups of patients with EGE and EC, the level of plolactin was significantly higher compared to the control group (499.4±336.72, р1,4<0.01 and 566.6±256.12 versus 237.8±126.43, р3,4=0.01, respectively). Sonographic parameters indicated increased endometrial thickness in the group of patients with EGE1 and EC3 compared to the control group4 (3.2±0.57 and 3.8±1.45 versus 2.9±0.51, р1,4=0.047 and р3,4=0.001) and echosonography results (0.7±0.31 and 0.9±0.40 versus 0.5±0.32, р1,4<0.01 and р3,4<0,01) confirmed a hyperestrogenic background in patients in these subgroups.

According to pelvic US, EGE was suspected only in 3.2% (3/94) of cases, ADM in 8,5% (8/94), and EC in 14,9% (14/94) of cases. According to MRI performed in 49 patients, EGE was suspected in 79.6% (39/49) of cases, ADM in 48.9% (24/49), and EC in в 10.2% (5/49) of cases.

We paid special attention to the analysis of interpretation of pelvic MRI scans and compared localization detected by MRI and laparoscopy for further identification of early signs of EGE in adolescents. According to factorial analysis based on MRI data, the most significant signs of EGE diagnosed in adolescents by instrumental methods included: small quantity of free fluid in the pouch of Douglas (87.2%, F=19.9, p<0.001), pelvic adhesion, fixation of the fallopian tube, intestine, ovaries (56.4%, F=9.52, р=0.002), heterogeneity of paraovarian, parametric, paracervical tissue, hypointense foci in tissue (51.3%, F=14.37, р<0.001), thickening or compaction of the uterosacral ligaments (43.6%, F=5.36, р=0.022), peritoneal compaction in the pouch of Douglas (12.8%, F=2.28, р=0.131).

According to the MRI data, in 48.9% (24/49) of patients with genital endometriosis ADM was suspected in the main group. Out of them, ADM was identified in nearly half of cases in patients with EGE (51.3% (20/39)). The most common signs of ADM in female adolescents were similar to the signs interpreted for adult patients with ADM, and had the following characteristics: irregular thickening of the uterine wall/asymmetric thickening of one of the layers of the uterine wall 75.0% (18/24); reduced differentiation in uterine zonal structures 50.0% (12/24); inhomogenous myometrial echotexture/increased MR signal in 83.3% (20/24) of cases; inhomogeneous, hypointense MR signal of endometrium in 100% (24/24) of cases; irregular thickening of the junctional zone in 58.3% (14/24) of cases; uneven contours of the junctional zone in 95.8% (23/24) of cases; inhomogeneous structure of the junctional zone in 75.0% (18/24) of cases.

Out of 79.6% (39) of patients , in whom EGE was identified using MRI, in most cases, the lesions were found in the uterosacral ligaments – 38.5% (15/39), along the broad ligament of the uterus (posterior leaf of the broad ligament) – 33.3% (13/39), in the peritoneum – 25.6% (10/39), endometrial foci and ovarian cysts – 12.8% (5/39), in the uterine isthmus – 2.6% (1/39).

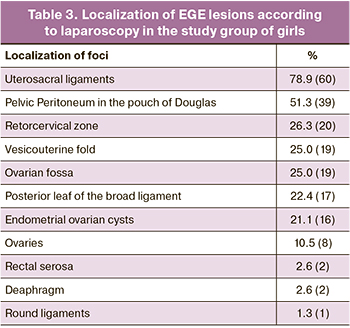

All patients in the main group with expressed NSAIDs-resistant dysmenorrhea and in the presence of suspected EGE and impossibility of diagnosing without surgery, underwent laparoscopic confirmation of the disease with subsequent histology of the foci. In total, laparoscopy was performed in 80 patients; out of them, EGE was identified in 95.0% (76/80), EC in 21.3% (17/80) of patients. According to laparoscopy, different localization of EGE lesions was found. The data are presented in Table 3. In adolescents with early forms of EGE, which were detected by diagnostic laparoscopy, the foci were predominantly localized in the uterosacral ligaments (78.9% (60/80)). In half of the patients the lesions were visualized in the pouch of Douglas (51.3% (39/80)); one third of female adolescents had disseminated endometriosis, and the lesions were found on the vesicouterine fold, in the retrocervical zone, ovarian fossa and broad ligament of the uterus.

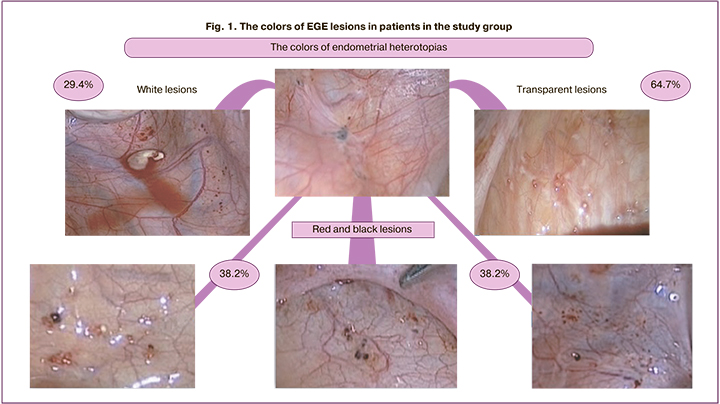

Confluent transparent lesions were found in most patients (64.7%), red and black lesions were in one third of patients (38.2%) and white fibrotic lesions were in 29.4% of patients (Fig. 1) Correlation analysis found that the lesions appearing black in color were identified in cases of severe stage of endometriosis according to AFS (r=0.382, p=0.045). Conversely, transparent lesions were observed in cases of mild stage of endometriosis according to AFS (r=-0.528, p=0.004).

We compared US data, interpretation of pelvic MRI scans and the laparoscopic images to understand the possibilities of non-invasive diagnosis of early forms of genital endometriosis.

The highest diagnostic accuracy of US in identifying different forms of endometriosis in adolescents was associated with EC in 77.8% (14/18) of cases; ultrasound findings helped to suspect ADM in 16.7% (8/48) of cases, and were indicative of EGE only in 4.1% (3/74) of cases.

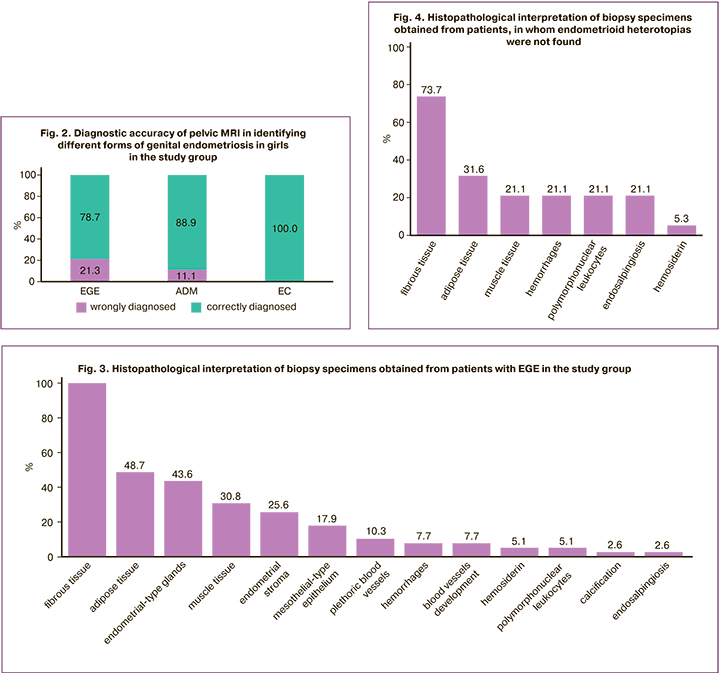

The diagnostic accuracy of MRI in patients with EGE was 79.6% (39/47), ADM – 88.9% (24/27), EC – 100% (5/5) (Fig. 2). Comparison between pelvic MRI data and laparoscopic diagnosis of EGE showed that in 75.5% (37) of patients with EGE, the diagnosis coincided with the results of surgical intervention. In 20.4% (10) of cases, the result was false negative, and in 4.1% it was false positive. Endometriosis lesions were not found during diagnostic laparoscopy (Fig. 2). It should be noted that in the presence of clinical symptoms even in the absence of suspected endometriosis according to MRI data, EGE was laparoscopically confirmed in 20,4% of cases among adolescent patients. MRI data versus the results of laparoscopy helped to suggest the direct localization of lesions in the uterosacral ligaments less than in half of the cases (38.5% (15/39)), in pelvic peritoneum only in a quarter of cases (25.6% (10/39)), along posterior leaf of the broad ligament of the uterus in 33,3% (13/39), and in the presence of ovarian lesions in 12.8% (5/39) of cases. Using laparoscopy, most often we saw that the lesions were localized in the uterosacral ligaments in 78.9% (60/80) of cases, in the pouch of Douglas in 51.3% (39/80) of cases, and in the retrocervical zone, vesicouterine fold and ovarian fossa in one third of cases.

Further, laparoscopically and histologically confirmed diagnoses of EGE and EC in 58 patients were compared. Macroscopic view of histological examination of endometriosis lesions presented endometrial heterotopias in 67.2% (39/58) of cases; in 32.8% (19/58) of cases heterotopias were absent. Endometriosis lesions were mainly presented as fibrous, adipose and muscle tissues, and the areas of hemorrhages (Fig. 3,4). Also, in 21.1% (4/58) of cases, tubal epithelium was visualized suggesting histological diagnosis of endosalpingiosis.

In 67.2% (39) of cases, in addition to endometrial heterotopias found during histological examination of EGE lesions, the areas of fibrous, adipose and muscle tissues, hemorrhages, vessels, the sites of calcification were seen. Some sites were infiltrated by polynuclear leukocytes, contained mesothelial epithelium. A combination of endosalpingiosis and endometrial heterotopias was identified in one of the cases (Fig. 5).

Thus, in 32.8% (19) of patients, histological image analysis did not find endometrial glandular epithelium or stroma in biopsy-proven lesions of endometrial heterotopias in pelvic peritoneum. However, such histological image was discordant with the areas of healthy peritoneum and did not exclude the diagnosis according to ESHRE 2022.

Discussion

Endometriosis is the leading pathological cause of dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain in adolescents. At the same time, there are very few clinical studies on endometriosis in adolescents in the scientific literature. Therefore, treatment strategy and tactics are extrapolated from the data obtained from adults. According to foreign and domestic researches, it is known that inherited predisposition, early age at menarche (<14 years), short menstrual cycle, longer menstrual bleeding, obesity, early onset of dysmenorrhea more than two times raise the risk of endometriosis [13–15]. In the course of our study, based on the patients’ anamnesis, we assessed the factors, which potentially could influence the risk of development of endometriosis. The significant risk factor was a hereditary burden of the disease, associated with endometriosis and other gynecological diseases (uterine fibroids, different types of cysts and endometrial hyperplasia) in the girls’ relatives, that increased the risk by 4.9 times (CI 1.58; 14.87, р=0.005). A number of studies reported that women with low body mass index are at high risk of developing endometriosis. This can be explained by the fact that high androgen levels mediated by hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance are often observed in obesity and associated with anovulation, irregular periods, and lower frequency of retrograde menstruation [16–18]. However, according to some authors, there is no correlation between body mass index and the risk for development of endometriosis [18, 19]. On the contrary, the results by other researchers showed, that obesity in childhood can be a risk factor for developing endometriosis in later life [20, 21]. It is suggested that due occurrence of menarche in obese girls at earlier age, the risk of developing endometriosis at a young age is higher, including due to a higher level of bioavailable estradiol, which is formed as a result of conversion of testosterone to estradiol by aromatase in adipose tissue, as well as high secretion of adipocytokines and leptin by adipose tissue, that create a pro-inflammatory microenvironment and has a pro-angiogenic effect [20].

Meta-analysis of 18 publications devoted to the study of association between the age at menarche and endometriosis showed a small increased risk of endometriosis with early menarche [2]. The authors believe that this may be based on early activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, high number of menstrual cycles during women’s lifetime and, respectively, the risk of retrograde blood flow to the peritoneal cavity. However, there are inconsistent data in literature reporting that the age of menarche is not associated with development of the disease or, conversely, early menarche is not a protective factor [22]. According to the data obtained in our study, the mean age of occurrence of menarche in girls with endometriosis was on average by 8 months lower (11.8±2.49) than in healthy girls (12.5±1.19) (р<0.001; t-test).

There are controversial data on association between the length of the menstrual cycle and development of endometriosis [23, 24]. According to some researches, a long menstrual cycle (>29 days) is associated with increased risk of developing endometriosis by 1.8 times [25]. However, according to other published data, shorter menstrual cycle (<27 days) is associated with a high incidence of the disease [26]. In our study, the statistical analysis did not find significant difference in the length of the menstrual cycle between the groups. At the same time, the girls with endometriosis had irregular periods more often compared to healthy girls (42 (42.9%) versus 7 (15.9%) (р=0.002, χ2-test)) and heavier menstrual bleeding (17 (32.1%) versus 4 (10.5%) (р=0.034, χ2-test)), that possibly can be a consequence a hyperestrogenic background, and coincides with the literature data [22] on a high risk of retrograde menstruation in cases of long and heavy menstrual bleeding [15].

The important link in the pathogenesis of endometriosis is the dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. The patients with endometriosis in the study group had higher levels of LH (8.3±6.72 versus 4.1 ±1.96, р<0.001) and prolactin (481.2±312.42 versus 237.8±126.43, р<0.001), that can be a predisposing factor for the development of endometriosis in girls with immature hypothalamic-pituitary complex and increased frequency and amplitude of LH secretion during puberty, including stress exposure. Also, the main group of patients had higher levels of estradiol (335.2±292.28 versus 171.5±73.95, р=0.032), 17-ОНP (5.8±3.63 versus 3.9±1.84, р=0.022), total androstenedione (10.8±4.27 versus 8.4±2.45, р=0.013), that indicated activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian and adrenal axis.

When US is performed by a highly qualified specialist, it can be suggested that ADM, EC and deep infiltrating endometriosis lesions can be found, especially in the intestinal wall, mainly in women of reproductive age [27]. In our study, US was informative only for the diagnosis of EC (77.8%), probably due to the fact that this process occurs less often in adolescents.

It is known that MRI has a higher accuracy in the diagnosis of ADM, EC, as well as superficial and deep infiltrative endometriosis, and helps to detect subperitoneal lesions, the involvement of adjacent organs, and severity of the adhesive process. [28]. According to the data obtained in our study, the diagnostic accuracy of pelvic MRI was significantly higher versus US data (in 82.3% of cases versus 4.1%); as well as highly accurate diagnoses of ADM and EC (88.9% versus 16.7%) and (100% versus 77.8%). The most significant signs of EGE according to MRI scans were identified using multifactorial analysis: small quantity of free fluid in the pouch of Douglas (87.2% (34), F=19.9 p<0,001); pelvic adhesion, fixation of the fallopian tube, intestine, ovaries (56.4% (22), F=9.52, р=0.002); heterogeneity of paraovarian, parametric, paracervical tissue, hypointense foci in tissue (51.3% (20), F=14.37, р<0.001); thickening or compaction of the uterosacral ligaments (43.6% (17), F=5.36, р=0.022); peritoneal compaction in the pouch of Douglas (12.8% (5), F=2.28, р=0.13).

In the scientific literature, there is a report on asymmetry of endometriosis lesion distribution and diffuse or local thickening of uterosacral ligaments, the presence of nodules with fuzzy stranding contours, which has characteristic image features for endometrial heterotopias [29]. According to some authors, retrocervical endometriosis often spreads to the rectovaginal septum, vagina and large bowel, leading to formation of extensive pelvic adhesions. Ovarian lesions may appear as superficial or deep lesions and include fiber density, or may represent EC. Endometrioma is a thick-walled retention cyst with repeated cyclical hemorrhages. It is characterized by a hyperintense MR signal on T1-weighted images (T1WI) and a heterogeneous MR signal on T2WI. It often has a two-layer structure, and is detected by MRI with high specificity up to 98% [8]. The signs of ADM on MRI, which were identified in our study were consistent with the literature data and in published data obtained by the group of authors headed by Prof. L.V. Adamyan, who described uneven thickening, uneven contours and heterogeneous structure of the transitional and junctional zone, the appearance of small heterogeneous inclusions and cystic components in the transitional and junctional zone, the detection of single small, unevenly located foci or zones of a heterogeneous structure in myometrium, the increased size and asymmetry of the uterus in reproductive aged women with ADM [1].

The gold standard to verify the diagnosis of endometriosis, determine the degree of infiltration and severity of the disease is laparoscopic confirmation of the diagnosis [30]. As noted earlier, endometrial lesions in adolescents often look different from those in adult women. Generally, confluent vesicular lesions exhibit transparent appearance, or have red, white, and/or yellowish brown color most commonly than black or blue color [31]. In our study, during laparoscopic visualization, multiple endometriosis lesions in adolescents appeared different in color: transparent in 64.7% of cases, red in 38.2%, black and blue in 38.2%, white in 29.4% cases.

In 1987, the study by Chatman D. ad и Zbella E., which included 115 patients with endometriosis, found that the disease could be histologically misdiagnosed even in the presence of macroscopically visible lesions [9]. Currently, the world community adheres to the tactics that the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis should not depend on histological confirmation of the diagnosis. The prospective study by Stratton P. et al. (2002) showed that a total of 314 endometriosis lesions were identified and excised in 65 patients, and histological confirmation was obtained only in 61% of cases [32].

The study by Marchino G. et al. analyzed 122 biopsies performed on 54 patients. Endometriosis was confirmed in 54 excised masses, when glandular and stromal components of the endometrial tissue were visualized [33]. The frequency of histological verification was significantly higher for the classic lesions represented by vesicular and papular lesions versus atypical lesions (64% versus 42%, р<0.05). Fibrotic sites were most frequently identified among the specimens, in which endometrial heterotopias were not found, and it was suggested that these lesions represented late stages in the natural course of the disease. Inconsistency between the visual ad histological diagnoses also was noted in our study, where in 32.8% (19) of cases, no endometrial heterotopias were found at biopsy sites. Most often, these lesions were represented as fibrous tissue in 73.7% (14), adipose tissue in 31.6% (6), muscle tissue in 21.1% (4) and the sites of hemorrhages in 21,1% (4) of cases.

According to publications, endometriosis lesions are most often confirmed histologically, when heterotopias are black in color, and multiple lesions appear white or different colors [34]. In our study, no association was found between the color of lesions and the probability of detecting endometrial tissue during pathohistological examination. However, according to our data, black lesions were identified at a more advanced stage of endometriosis according to AFS (r=0.382, p=0.045), and higher AFS scores (r=0.443, p=0.018). On the contrary, identification of transparent lesions was observed for mild endometriosis according to the scoring system of the disease severity (r=-0.528, p=0.004). Еl Bishry G. et al. showed, that with greater severity, the probability of histological confirmation of the disease was higher [4]. Our study did not find this association (r=-0.096, p=0.626). However, the sample of the study included the patients mainly with early forms of the disease, which were manifested in adolescence. According to some publications, the stage of the disease does not correlate with the severity of symptoms [35–37]. Also in our study, association between the stage of the disease and the severity of dysmenorrhea according to VAS scores was not found (r=0.205, p=0.483).

It should be noted that surgical tactics for management are considered, when it is impossible to make a diagnosis without surgical intervention in cases of early forms of the disease further requiring long-term conservative hormonal therapy, or in cases of failure of conservative treatment, and when deep infiltrating lesions invade the adjacent organs. In patients with ovarian endometriomas (up to 4–5 cm in diameter), when ADM or EGE is visualized by ultrasound or MRI, non-surgical management is preferable as the first step [32, 36, 37].

Conclusion

Therefore, considering the cronic character of the disease, the impact of endometriosis on young patients’ reproductive function, ovarian reserve, social and psychological status, currently, the major objective is to identify the disease as early as possible, and timely to start treatment with purpose of preventing the progression of the disease and development of complications. Despite the fact that there are still no reliable biomarkers or other non-invasive diagnostic methods, constellation of clinical and anamnestic symptoms, the data of gynecologic examination and instrumental methods (pelvic US in cases of EC and MRI in cases of EGE) make it possible to suspect manifestation of early forms of genital endometriosis in young patients. When the diagnosis cannot be made without surgical intervention, laparoscopic surgery and histological examination of endometriosis lesions is an important step in the diagnosis of endometriosis in young patients with chronic pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea, which is not amenable to drug treatment. However, the cells of endometrial heteropias are not always present in biopsy specimens, and this does not exclude the diagnosis of endometriosis in patients with clinical symptoms and visual confirmation according to the laparoscopic data.

The following can be concluded from the conducted research:

1. The adolescent patients with genital endometriosis had a hereditary burden of the disease versus healthy girls. This increased the risk of development of the disease by 4.9 times (CI=1.58; 14.87, р=0.005), early menarche (11.8 years, р<0.001), more frequently heavy (р=0.034) and irregular (р=0.002) menstrual bleeding. The major complain of patients with endometriosis was pain, which scored 8–9 points according to VAS, and on average, occurred a day prior to the period, lasted for the first 3–4 days (40.8%), and was resistant to NSAIDs.

2. The patients with genital endometriosis, compared to healthy girls, had higher levels of LH (р<0.001), estradiol (р=0,032), 17-OHP (р=0.022), androstenedione (р=0,014), that indicated activation of steroidogenesis. According to US data, in girls with genital endometriosis, the parameters of M-echo (p<0.001) and uterine thickness (p=0.001) were higher compared to the control group probably due to hyperestrogenism associated with endometriosis.

3. In diagnosing genital endometriosis in adolescents, pelvic US was informative for the diagnosis of EC (77.8%), and virtually did not help to identify early forms of EGE (4,1%). The accuracy for diagnosis of EC using pelvic MRI was 100%, ADM – 88.9%. According to MRI, the significant signs of EGE were: thickening of the uterosacral ligaments (р=0.022), heterogeneity of pelvic tissue (р<0.01), especially in combination with adhesions (р=0.002) or fluid in the pouch of Douglas (р<0.01), that made it possible to suggest EGE in 78.7% of cases. No indications for the presence of genital endometriosis according to MRI data (in 21.3% of cases) did not exclude the presence of genital endometriosis in adolescents. Therefore, in the presence of persistent clinical symptoms, the use of diagnostic laparoscopy was justified.

4. In 67.2 of cases, the histolgical image of endometriosis lesions was represented as endometrial glandular epithelium and stroma; in 32.8 % of cases, as fibrous, adipose and muscle tissues with the areas of hemorrhages, that did not exclude the diagnosis of EGE and suggested the same principles of further management and treatment of patients.

References

- Адамян Л.В., ред. Эндометриоз: диагностика, лечение и реабилитация. Федеральные клинические рекомендации по ведению больных. М.; 2013. 64с. [Adamyan L.V., ed. Endometriosis: diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation. Federal Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Patients. Moscow; 2013. 64p. (in Russian)].

- Ashrafi M., Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S., Akhoond M.R., Talebi M. Evaluation of risk factors associated with endometriosis in infertile women. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2016; 10(1): 11-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.22074/ijfs.2016.4763.

- Janssen E.B., Rijkers A.C., Hoppenbrouwers K., Meuleman C., D'Hooghe T.M. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2013; 19(5): 570-82. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt016.

- Bishry G. El, Tselos V., Pathi A. Correlation between laparoscopic and histological diagnosis in patients with endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008; 28(5):511-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01443610802217918.

- Ballweg M.L. Big picture of endometriosis helps provide guidance on approach to teens: comparative historical data show endo starting younger, is more severe. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2003; 16(3, Suppl.): S21-6.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1083-3188(03)00063-9.

- Simoens S., Dunselman G., Dirksen C., Hummelshoj L., Bokor A., Brandes I. et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum. Reprod. 2012; 27(5): 1292-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des073.

- Laufer M.R., Sanfilippo J., Rose G. Adolescent endometriosis: diagnosis and treatment approaches. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2003; 16(3, Suppl.): S3-11. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1083-3188(03)00066-4.

- Chamié L.P., Blasbalg R., Pereira R.M.A., Warmbrand G., Serafini P.C. Findings of pelvic endometriosis at transvaginal US, MR imaging, and laparoscopy. Radiographics. 2011; 31(4): E77-100. https://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.314105193.

- Chatman D.L., Zbella E.A. Biopsy in laparoscopically diagnosed endometriosis. J. Reprod. Med. 1987; 32(11): 855-7.

- de Sanctis V., Matalliotakis M., Soliman A.T., Elsefdy H., Di Maio S.,Fiscina B. A focus on the distinctions and current evidence of endometriosis in adolescents. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018; 51: 138-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.023.

- Sachedina A., Todd N. Dysmenorrhea, endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in adolescents. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020; 12(Suppl. 1): 7-17.https://dx.doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2019.2019.S0217.

- Patel B.G., Lenk E.E., Lebovic D.I., Shu Y., Yu J., Taylor R.N. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: Interaction between Endocrine and inflammatory pathways. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018; 50: 50-60.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.006.

- Buck Louis G.M., Hediger M.L., Peña J.B. Intrauterine exposures and risk of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2007; 22(12): 3232-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dem338.

- Nnoaham K.E., Webster P., Kumbang J., Kennedy S.H., Zondervan K.T.Is early age at menarche a risk factor for endometriosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Fertil. Steril. 2012; 98(3): 702-12. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.035.

- Wei M., Cheng Y., Bu H., Zhao Y., Zhao W. Length of menstrual cycle and risk of endometriosis: a meta-analysis of 11 case-control studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95(9: e2922. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002922.

- Farland L.V., Missmer S.A., Bijon A., Gusto G,. Gelot A., Clavel-Chapelon F. et al. Associations among body size across the life course, adult height and endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2017; 32(8): 1732-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex207.

- Shah D.K., Correia K.F., Vitonis A.F., Missmer S.A. Body size and endometriosis: results from 20 years of follow-up within the Nurses’ Health Study II prospective cohort. Hum. Reprod. 2013; 28(7): 1783-92. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det120.

- Tang Y., Zhao M., Lin L., Gao Y., Chen G.Q., Chen S., Chen Q. Is body mass index associated with the incidence of endometriosis and the severity of dysmenorrhoea: a case-control study in China? BMJ Open. 2020; 10(9): e037095. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037095.

- Liu Y., Zhang W. Association between body mass index and endometriosis risk: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017; 8(29): 46928-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14916.

- Nagle C.M., Bell T.A., Purdie D.M., Treloar S.A., Olsen C.M., Grover S.,Green A.C. Relative weight at ages 10 and 16 years and risk of endometriosis: a case-control analysis. Hum.Reprod. 2009; 24(6): 1501-6.https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep048.

- Tilg H., Moschen A.R. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006; 6(10): 772-83.https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri1937.

- Li X., Guo L., Zhang W., He J., Ai L., Yu C. et al. Identification of potential molecular mechanism related to infertile endometriosis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022; 9: 845709. https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.845709.

- Calhaz-Jorge C., Mol B.W., Nunes J., Costa A.P. Clinical predictive factors for endometriosis in a Portuguese infertile population. Hum. Reprod. 2004; 19(9): 2126-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh374.

- Hemmings R., Rivard M., Olive D.L., Poliquin-Fleury J., Gagné D., Hugo P., Gosselin D. Evaluation of risk factors associated with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2004; 81(6): 1513-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.038.

- Sangi-Haghpeykar H., Poindexter A.N. 3rd. Epidemiology of endometriosis among parous women. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995; 85(6): 983-92.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0029-7844(95)00074-2.

- Moini A., Malekzadeh F., Amirchaghmaghi E., Kashfi F., Akhoond M.R.,Saei M., Mirbolok M.H. Risk factors associated with endometriosis among infertile Iranian women. Arch. Med. Sci. 2013; 9(3): 506-14.https://dx.doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2013.35420.

- Piketty M., Chopin N., Dousset B., Millischer-Bellaische A.E., Roseau G., Leconte M. et al. Preoperative work-up for patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis: transvaginal ultrasonography must definitely be the first-line imaging examination. Hum. Reprod. 2009; 24(3): 602-7.https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/den405.

- Coutinho A. Jr, Bittencourt L.K., Pires C.E., Junqueira F., Lima C.M., Coutinho E. et al. MR imaging in deep pelvic endometriosis: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2011; 31(2): 549-67. https://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.312105144.

- Del Frate C., Girometti R., Pittino M., Del Frate G., Bazzocchi M., Zuiani C.Deep retroperitoneal pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging appearance with laparoscopic correlation. Radiographics. 2006; 26(6): 1705-18.https://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.266065048.

- Dunselman G.A.J., Vermeulen N., Becker C., Calhaz-Jorge C., D'Hooghe T., De Bie B. et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014; 29(3): 400-12. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det457.

- Lu M.Y., Niu J.L., Bin Liu B. The risk of endometriosis by early menarche is recently increased: a meta-analysis of literature published from 2000 to 2020. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022; Apr 4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06541-0.

- Stratton P., Winkel C. A., Sinaii N., Merino M.J., Zimmer C., Nieman L.K. Location, color, size, depth, and volume may predict endometriosis in lesions resected at surgery. Fertil. Steril. 2002; 78(4): 743-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03337-x.

- Marchino G.L., Gennarelli G., Enria R., Bongioanni F., Lipari G., Massobrio M.Diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis with use of macroscopic versus histologic findings. Fertil. Steril. 2005; 84(1): 12-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.09.042.

- Ueki M., Saeki M., Tsurunaga T., Ueda M., Ushiroyama N., Sugimoto O. et al. Visual findings and histologic diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis under laparoscopy and laparotomy. Int. J. Fertil. Menopausal Stud. 1995; 40(5): 248-53.

- Liakopoulou M.-K., Tsarna E., Eleftheriades A., Kalampokas E., Liakopoulou M.K., Christopoulos P. Medical and behavioral aspects of adolescent endometriosis: a review of the literature. Children (Basel). 2022; 9(3): 384. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/children9030384.

- Туманова У.Н., Щеголев А.И., Павлович С.В., Серов В.Н. Факторы риска развития эндометриоза. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 2: 68-75. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.2.68-75. [Tumanova U.N., Shchegolev A.I., Pavlovich S.V., Serov V.N. Risk factors for the development of endometriosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; 2: 68-75. (in Russian)].https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.2.68-75.

- Ярмолинская М.И., Сейидова Ч.И., Пьянкова В.О. Современная тактика назначения медикаментозной терапии генитального эндометриоза. Акушерство и гинекология. 2021; 4: 55-62. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.4.55-62. [Yarmolinskaya M.I., Seyidova Ch.I., Pyankova V.O. Modern tactics of prescribing drug therapy for genital endometriosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 4: 55-62. (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.4.55-62.

Received 14.07.2022

Accepted 12.10.2022

About the Authors

Elena P. Khashchenko, PhD, Senior Researcher at the 2nd Gynecological (child and adolescent) Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health Russia, khashchenko_elena@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3195-307X,117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Elvina Z. Allakhverdieva, student of Faculty of Fundamental Medicine, M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, elya.elya2014@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7750-4675, 119991, Russia, Moscow, Lomonosovsky Prospekt, 27-1.

Elena V. Uvarova, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Corresponding Member of the RAS, Head of the 2nd Gynecological (child and adolescent) Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, elena-uvarova@yandex.ru,

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3105-5640, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Vladimir D. Chuprynin, PhD, Head of General Surgery Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, v_chuprynin@oparina4.ru, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Elena A. Kulabukhova, PhD, Doctor at the Department of Radiation Diagnostics, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics,

Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, e_kulabukhova@oparina4.ru, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Irina A. Luzhina, Doctor at the Department of Radiation Diagnostics, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, i_luzhina@oparina4.ru, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Fatima Sh. Mamedova, PhD, Doctor at the Department of Ultrasound Diagnostics in Neonatology and Pediatrics, Academician V.I. National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, mamedova_f@mail.ru, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Polina V. Uchevatkina, Doctor at the Department of Radiation Diagnostics, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, p_ uchevatkina@oparina4.ru, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Aleksandra V. Asaturova, PhD, Head of the 1th Pathology Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, a_asaturova@oparina4.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8739-5209, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Anna V. Tregubova, clinician-pathologist of the 1th Pathology Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, a_tregubova @oparina4.ru, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Alina S. Magnaeva, clinician-pathologist at the 1th Pathology Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Сenter for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia, a_magnaeva @oparina4.ru, 117997, Russia, Moscow, Ac. Oparina str., 4.

Authors’ contributions: Khaschenko E.P., Allakhverideva E.Z. – the concept of the study, literature searching and analysis, formulation of research objective and the design of the study, writing and editing the text of the article; Khaschenko E.P., Uvarova E.V., Chuprynin V.D. – management and treatment of patients, analysis and interpretation of the patients’ data and surgical intervention; Mamedova F.Sh. – performance of pelvic ultrasound examination and analysis of the results;

Luzhina I.A., Kulabykhova E.A., Uchevatkina P.V. – performance of pelvic MRI, description and analysis of the results, identification of significant factors; Asaturova A.V., Tregubova A.V., Magnaeva A.S. – carrying out pathomorphological study and analysis of the results, Khaschenko E.P., Uvarova E.V. – final editing of the article.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding: The study was carried out with the financial support of State Assignment No. 18-A21 of the Ministry of Health of Russia “The role of impaired energy metabolism and immune protection in development of different forms of endometriosis, development of individual therapy and prediction of its effectiveness in early reproductive period (from menarche to 18 years).

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Ministry of Health of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors’ Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Khaschenko E.P., Allakhverideva E.Z., Uvarova E.V., Chuprynin V.D., Kylabukhova E.A., Luzhina I.A., Uchevatkina P.V., Mamedova F.Sh., Asaturova A.V., Tregubova A.V., Magnaeva A.S. Clinical and diagnostic features of different

forms of genital endometriosis in female adolescents.

Akusherstvo i Gynecologia/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 11: 109-121 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.11.109-121