Clinical and anatomical features of patients with apical prolapse

Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S., Matskevich E.N.

Objective: To study clinical and anatomical features of patients with apical prolapse (AP).

Materials and methods: 230 medical records of patients with pelvic organ prolapse who underwent examination and treatment from 2019 to 2024 at the University Clinic "I am healthy!" were analyzed. The main patient group consisted of 130 women with apical prolapse, the comparison group included 100 patients with anterior/posterior vaginal wall prolapse without apical prolapse. Evaluation was performed according to the POP-Q classification, using standard questionnaires (POPDI-6, UDI-6) and clinical examination.

Results: Patients with apical prolapse more often reported incomplete bladder emptying and the need to reduce prolapse to ease voiding. In the comparison group, stress urinary incontinence and lower abdominal pressure were more common. In almost half of the patients with apical prolapse, the leading point was Ba (44.6%). In patients without apical prolapse, prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall (point Bp) occurred most often (62%). No significant differences in symptoms were found between the groups, which complicates the early diagnosis of apical prolapse.

Conclusion: When examining the patients with pelvic organ prolapse and collecting their history, it is necessary to take into account the "pitfalls" that complicate objective diagnosis of apical prolapse. It is necessary to improve the technique of physical examination of gynecological patients for early detection of first-level support defects, which will allow timely prescription of adequate treatment with the best long-term results.

Authors’ contributions: Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S. – study concept and design, editing; Matskevich E.N. – data collection and analysis; Matskevich E.N., Dubinskaya E.D. – text writing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Funding: The study was performed without external funding.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee of Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University of Russia.

Patient Consent for Publication: All patients provided informed consent for the publication of their data.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S., Matskevich E.N. Clinical and

anatomical features of patients with apical prolapse.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (7): 130-137 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.154

Keywords

The incidence of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is widespread and according to the literature reaches 65%: when assessing the cause of symptoms it goes up to 31%, on examination – 10–50% and with comprehensive assessment – 20–65% [1]. It is impossible to determine the exact cause of POP due to several factors: using various classification systems, extensive studies, concomitant symptomatic and asymptomatic prolapses, as well as unknown number of women who do not seek medical care for this problem [2]. Some authors state the average global rate of POP as 30.9% [3].

Although the incidence of apical prolapse (AP) within the POP structure is only 5–15%, it plays a major role in providing support to the pelvic floor in general [3]. It requires careful diagnosis and more extensive surgeries associated with a certain list of complications [4].

The average risk of undergoing surgery for POP is 12.6%, while the recurrence rate when using patient’s own tissue within 2 years is almost 25%, and within 5 years it comprises up to 46% [5].

According to generally accepted criteria, the hymen represents an important point in the formation of symptoms associated with prolapse of the anterior and posterior vaginal wall, while the concept of "normal apical support" is defined much less precisely [6]. Taking into account the accumulated fundamental data [7–9], the case when point C<(-TVL/2), or when point C is located lower than half the length of the vagina, this can be regarded as "apical prolapse" [10].

To date, there is no data on the point C position that makes AP “symptomatic”. Moreover, the clinical significance of AP where point C is located above the hymen has not been verified [6]. However, it is known that in approximately half of the cases of prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall, there is a defect in apical support [2]. We have also previously found that the frequency of initial forms of AP in the anterior vaginal wall prolapse of stage 2–3 reaches 48% [11].

However, the presence of minor and moderate forms of AP (if the apex does not extend beyond the hymenal ring), especially in the presence of a marked cystocele, is often not diagnosed. Underestimation of AP, as well as its stage, leads to incorrect planning of the scope of surgery, as well as to a high frequency of relapses after surgical treatment [12]. Particular difficulties can be caused by the diagnosis of unexpressed forms, when point C has +/-1 (POP-Q) coordinates. We believe these difficulties may be associated with various anatomical features of prolapse, which must be taken into account when diagnosing this disease.

The aim of this study was to investigate the clinical and anatomical features in patients with AP.

Materials and methods

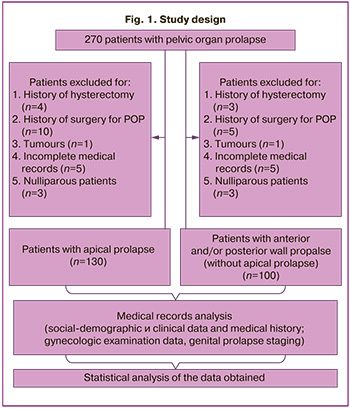

A single-center clinical retrospective case-control study with the simple random selection included 270 women with POP who were examined and treated over the period of 2019–2024 within the clinical base of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with a course in Perinatology of the Medical Institute of Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (Head of the Department – Honored Scientist of the Russian Federation, Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. V.E. Radzinsky) at the University Clinic of Reproduction and Operative Gynecology "I am healthy!" All patients signed a voluntary informed consent to participate in this study.

Criteria for cases and controls selection: patients were randomly selected from the clinic database. The selection was carried out among those who met the inclusion criteria: POP, aged over 18 years, availability of complete medical records. Patients with concomitant severe diseases that could affect the results of the study were excluded.

A number of patients prematurely discontinued participation as they did not meet the eligibility criteria, thus reducing the overall number of participants to the current number (n=230). The following patient groups were excluded:

- history of hysterectomy (n=7);

- history of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse (n=15);

- malignant neoplasms (n=2);

- incomplete medical records (n=10);

- nulliparous (n=6).

After checking the patients for compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, they were divided into 2 groups. The main group inclusion criteria were any stage of AP (point C below -3 cm (POP-Q) [13]) (incomplete and complete uterine prolapse [N 81.2; N 81.3]) and previous vaginal delivery. In the presence of any degree of AP, even when point C was not the leading point according to the POP-Q classification, the patient was assigned to the main group.

Main group exclusion criteria: history of hysterectomy; history of pelvic organ prolapse surgery; malignant neoplasms; incomplete medical records; nulliparous patients. After a group check for inclusion/exclusion criteria, 130 women with vaginal delivery with underlying AP were included in the main (case) group.

The inclusion criterion for the control group was the anterior and/or posterior vaginal walls prolapse without AP in women with vaginal delivery.

The control group exclusion criteria: combination of vaginal wall prolapse and AP; history of hysterectomy; history of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse; malignant neoplasms; incomplete medical documentation; nulliparous patients.

After checking for inclusion/exclusion criteria, 100 women with vaginal delivery in the setting of anterior/posterior vaginal wall prolapse without AP (point C above -3 cm) (POP-Q) were included in the control group [13] ([N 81.1; N 81.6]).

The study design is presented in Figure 1.

Sample Representativeness: all patients included in the study represented a typical population of women with POP observed at the University Clinic "I am healthy!" during the stated period. This population is characterized by a wide range of socio-demographic aspects, generalizing women with POP receiving treatment in similar health cate settings.

The initial examination included patient history and clinial data collection, physical and gynecological examination, including analysis of anatomy.

All patients underwent POP assessment using the international POP-Q classification [13]. During the gynecological examination, the main parameters were measured during the Valsalva maneuver (Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp, C, D, gh, pb) and at rest (TVL). Stress urinary incontinence was assessed based on the cough test during the physical examination.

To assess prolapse symptoms and quality of life, questionnaires for the diagnosis of prolapse – POPDI-6 [14] and the questionnaire on urinary incontinence (UDI-6) [14] were used.

Statistical analysis

To analyze the results, we used statistical computer programs (SPSS version 10.0.7 and Statistica version 10.0), and some calculations were performed using Excel tables.

For each group of patients, the distribution of quantitative indicators was tested for compliance with the normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. When describing normally distributed indicators, we used the arithmetic mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) as M (SD). When distributing features that differ from normal, we used descriptions in the form of the median (Me) and interquartile range as Me (Q1; Q3). Qualitative indicators are presented both in absolute (n) and relative (%) values.

To compare dichotomous indicators between independent samples, the Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for small samples were used. To compare qualitative indicators with 0% or 100% values, the Z-test with endpoint adjustment was used (in case of comparing 0% or 100, the calculation was made using the Z-test for two proportions). When comparing quantitative indicators in groups, the Student and Mann–Whitney tests were used. The critical level of significance in testing statistical hypotheses was 0.05.

Results

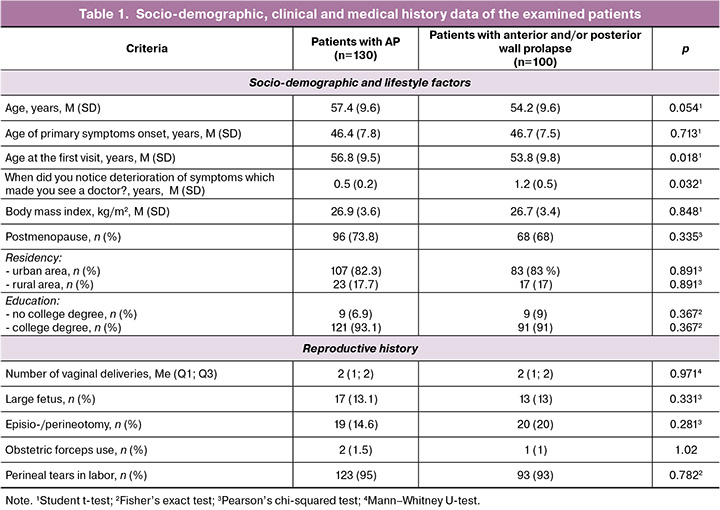

The socio-demographic, clinical and medical history data of the examined patients are presented in Table 1.

Thus, the study groups were comparable: the average age of patients in the main and comparison groups was 57.3 (9.6) and 54.2 (9.6) years, respectively (p>0.05). The study groups did not differ in parity and basic socio-demographic characteristics. The mean age of onset of symptoms, the incidence of birth trauma, episio-/perineotomy and operative vaginal delivery with obstetric forceps did not differ significantly. As a rule, patients with apical prolapse tended to seek medical care on average 4 years later than patients with vaginal wall prolapse.

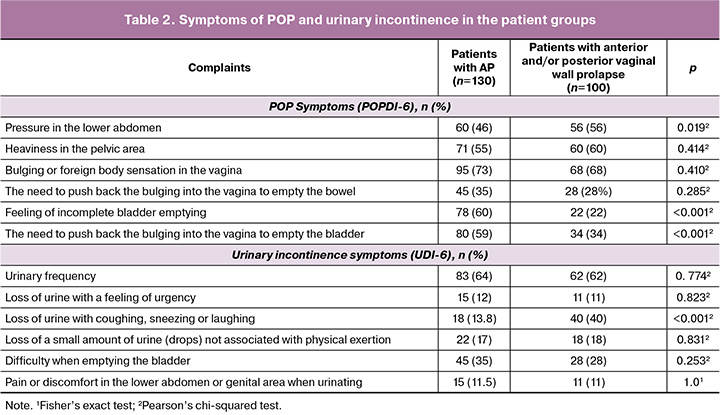

In accordance with the stated goal, the analysis of the patients’ complaints and their prevalence in the examined groups was conducted (Table 2).

As follows from the data presented, patients with AP significantly more often complained of "a feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder" and "the need to reduce the bulging in order to empty the bladder." In turn, patients with vaginal wall prolapse and without AP more often reported urine loss associated with coughing, sneezing or laughing, and pressure in the lower abdomen.

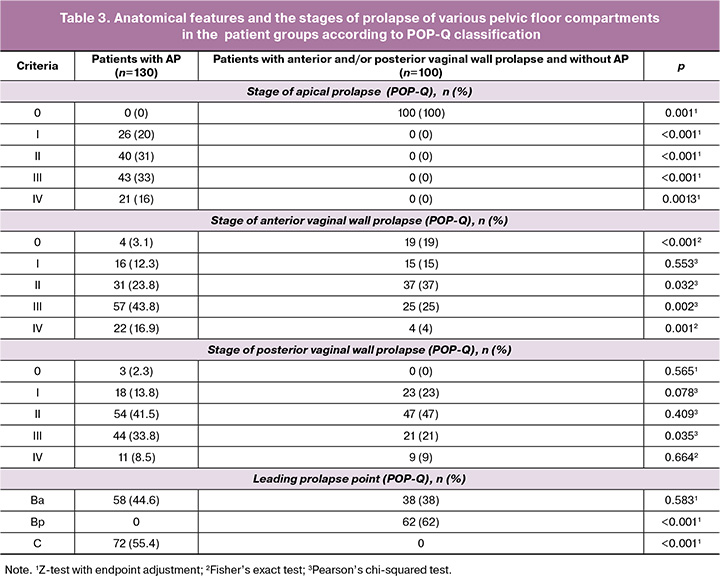

At the next stage, we assessed the severity of prolapse of the various pelvic floor compartments (with or wothout AP) in the patient groups (Table 3).

The results of the analysis show that patients with stages II and III of AP most often seek help, with 43.8% of them having stage III prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall. The result of the study demonstrating the fact that in almost half of the cases the leading point among patients with AP is Ba (44.6%) deserves special attention. At the same time, in patients without AP (comparison group), cases of prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall, when the leading point of prolapse is Bp (62%), are most often registered.

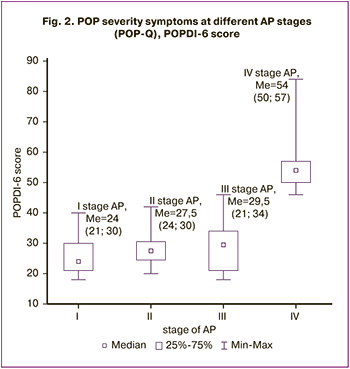

During the study, the severity of symptoms at different stages of AP was assessed using the POPDI-6 questionnaire; the data are presented in Figure 2.

When analyzing the obtained results, a significant increase in POPDI-6 score was revealed at stage IV of AP, compared with stages I–III (p<0.001). At earlier stages of AP, no significant differences in the severity and characteristics of patients' complaints were identified.

Discussion

The study showed that in about half of the AP patients, especially at stages I–III, the leading point was Ba, which complicated the diagnosis of the apical support defect. At the same time, in almost half of the AP patients, the stage of prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall reached stage III (POP-Q).

No significant differences in clinical symptoms were found in the absence or presence of AP. However, among patients with AP, complaints of “a feeling of incomplete emptying of the bladder” and “the need to reduce the protrusion in order to empty the bladder” were significantly more often recorded. At the same time, stress urinary incontinence is associated with AP in only 10–13% of cases, i.e. it occurs quite rarely.

The data obtained in this study also indicates that the AP symptoms, which motivate patients to seek medical care, do not significantly differ between stages I–III. This is obviously the reason why patients postpone visits to the doctor. This fact may explain our findings that about 10 years pass between the moment the first symptoms occur and the first visit to the doctor. It should also be noted that, when answering the question on how long ago they noticed the deterioration that made then visit the doctor (Table 1), patients pointed that the deterioration occurred recently, although the prolapse had been developing for many years.

Any diagnosis in medicine is carried out on the basis of complaints, history data, results of examination, as well as additional laboratory and instrumental studies if necessary. A comprehensive assessment of all the listed factors allows one to establish an accurate diagnosis and find the optimal treatment tactics.

The main goal of patients planning to undergo treatment for POP is to reduce the disturbing symptoms [15]. According to the results of this study, the presence of AP does not mean any pathognomonic complaints that allow us to suggest a diagnosis. Our data coincide with the literature, indicating that prolapse symptoms often do not correlate with its localization and severity; moreover, they often occur only when the protrusion reaches the projection of the hymen [16].

Moreover, there is some controversy on the position of point C that can be considered as AP. Today, most researchers are inclined to believe that the cutoff point of position C is 5 cm; these values are considered to be predictors of the prolapse symptoms [8, 9]. It should be emphasized that we are not talking about the appearance of the first symptoms, but about the deterioration of the condition, which encouraged a woman to visit the doctor. This indicates the specificity of the symptoms and the fact that, apparently, adaptation to disorders of the anatomy and function of the pelvic floor occurs until a certain critical point of protrusion is reached, which is individual in each case.

Our data indicate that no significant differences in the quality of life with prolapse of the vaginal walls only and/or in combination with AP were identified. Thus, the patients' subjective assessment of their condition does not allow us to determine even approximately which compartment is being discussed without a special examination.

This is consistent with literature analysis according to which assessing the severity of prolapse without physical examination, based only on clinical symptoms, will obviously identife only women with advanced stages of the disease [16].

Quality of life questionnaires are based on specifying the extent to which bladder, bowel and vaginal symptoms affect daily activities, relationships and emotional state of women with pelvic floor disorders [17]. However, it has been established that when analyzing complaints from patients with POP, even the wording of the question is of great importance. Thus, one of the fundamental population studies stated that an affirmative answer to the question “Do you feel vaginal protrusion?” has a sensitivity of only 66.5% and a specificity of 94.2% in comparison with an objective assessment of the prolapse with the POP-Q system [18]. Despite the fact that the “bulging” symptom is the most discriminatory among the others, according to the data we obtained, it does not have a key significance in the diagnosis of AP.

Clinical examination (without assessing the severity of symptoms that bother the patient) of patient with prolapse is also very subjective. Thus, the frequency of prolapse POP-Q≥II during physical examination, according to scientific data, ranges from 1.18 to 64.8%, while the frequency of AP ranges from 2 to 21.2% [1]. The most controversial is stage II of genital prolapse, since it includes the position of the leading point both below and above the hymen (from -1 to +1). If the leading point of prolapse is located above the hymen, then the presence of prolapse does not match with the international definition of this condition. First of all, it impleis “protrusion” [6]. A number of researchers even propose dividing this stage of prolapse into IIa (-1–0) and IIb (>0/+1), however, to date, this proposal has not been validated from a clinical point of view [13].

Unfortunately, the value of ultrasound in diagnosing AP is insignificant, despite the low cost and availability of this method. This is due to the fact that the interpretation of the results of transperineal ultrasound examination can be quite complex because of the isoechoic nature of the uterus and vagina, which produces an acoustic shadow due to the density of the myometrium. Also there is difficulty in visualizing the normal postmenopausal uterus due to its small size, as well as the inaccessibility of visualizing a normally (highly) located uterus using this approach [19].

Is it so important to accurately determine the position of point C if it is not the leading one? In our opinion, it is critically important, since the position of apex determines the further treatment strategy in combination with prolapse of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Inadequate correction of level I support during reconstruction of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls leads to relapses [20, 21].

Thus, the diagnosis of early stages of AP is complex and is often carried out in the presence of its marked forms (uterine prolapse). This is primarily due to the fact that the assessment of AP based on patients’ complaints is very subjective, since there is no pathognomonic symptom that allows one to assume the presence of the first level pelvic prolapse. Secondly, the presence of AP in most cases is associated with a advanced prolapse of the anterior compartment, which “hides” the true position of point C. The frequency of isolated forms of AP, when the prolapse of the anterior/posterior walls does not exceed stage I, occurs in only 15% of cases.

Conclusion

The obtained study results indicate that it is necessary to take into account "pitfalls" when collecting history data and conducting examination of patients with genital prolapse. Patients with AP may have a number of anatomical features, including the most prominent point Ba in almost half of the cases, which complicate diagnosis and lead to planning an inadequate volume of surgical intervention. It should be especially noted that there are no pathognomonic complaints, while the severity of symptoms does not differ significantly in the presence of stages I–III of AP. It is necessary to improve the examination methodology for better determination of point C, which will allow timely treatment at early stages of AP with the best long-term results.

References

- Brown H.W., Hegde A., Huebner M., Neels H., Barnes H.C., Marquini G.V. et al. International urogynecology consultation chapter 1 committee 2: Epidemiology of pelvic organ prolapse: prevalence, incidence, natural history, and service needs. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022; 33(2): 173-87. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-05018-z

- Zumrutbas A.E. Understanding pelvic organ prolapse: a comprehensive review of etiology, epidemiology, comorbidities, and evaluation. Soc. Int. Urol. J. 2025; 6: 6. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/siuj6010006

- Hadizadeh-Talasaz Z., Khadivzadeh T., Mohajeri T., Sadeghi M. Worldwide prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. J. Public. Health. 2024; 53(3): 524-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v53i3.15134

- Смольнова Т.Ю., Красный А.М., Чупрынин В.Д., Садекова А.А., Чурсин В.В., Тамбиева Ф.Р. Способ хирургической коррекции пролапса гениталий у пациентки со сниженным уровнем экспрессии гена CACNA1C в круглых связках матки. Акушерство и гинекология. 2020; 12: 234-41. [Smolnova T.Yu., Krasny A.M., Chuprynin V.D., Sadekova A.A., Chursin V.V., Tambieva F.R. Smolnova T.Yu., Krasnyi A.M., Chuprynin V.D., Sadekova A.A., Chursin V.V., Tаmbieva F.R. Surgical procedure to correct genital prolapse in a patient with reduced CACNA1C gene expression in the round ligament of the uterus. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020; (12): 234-41 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2020.12.234-241

- Komesu Y.M., Dinwiddie D.L., Richter H.E., Lukacz E.S., Sung V.W., Siddiqui N.Y. et al. Defining the relationship between vaginal and urinary microbiomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020; 222(2): 154.e1-e10. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.011

- Kowalski J.T., Barber M.D., Klerkx W.M., Grzybowska M.E., Toozs-Hobson P., Rogers R.G. et al. International urogynecological consultation chapter 4.1: definition of outcomes for pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023; 34(11): 2689-99. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05660-9

- Patnam R., Edenfield A., Swift S. Defining normal apical vaginal support: a relook at the POSST study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020; 30(1): 47-51. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3681-8

- Trutnovsky G., Robledo K.P., Shek K.L., Dietz H.P. Definition of apical descent in women with and without previous hysterectomy: a retrospective analysis. PLOS One. 2019; 14(3): e0213617. https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213617

- Dietz H.P., Mann K.P. What is clinically relevant prolapse? An attempt at defining cutoffs for the clinical assessment of pelvic organ descent. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2014; 25(4): 451-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2307-4

- Oh S., Shin E.K., Lee S.Y., Kim M.J., Lee Y., Jeon M.J. Anatomic criterion for clinically relevant apical prolapse in urogynecology populations. Urogynecology. 2023; 29(11): 860-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000001383

- Dubinskaya E.D., Gasparov A.S., Babichev A.I., Kolesnikova S.N. Improving of long-term follow-up after cystocele repair. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2022; 51(2): 102278. https://dx.doi.org/0.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102278

- Szymanowski P., Szepieniec W. K., Szweda H., Ligeza J., Sadakierska-Chudy A. Apical defect - the essence of cystocele pathogenesis? Ginekol Pol. 2024; 95 (7): 511-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.5603/GP.a2023.0022

- Haylen B.T., Maher C.F., Barber M.D., Camargo S., Dandolu V., Digesu A. et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) / International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016; 27(2): 165-94. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2932-1

- Barber M.D., Walters M.D., Bump R.C. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005; 193(1): 103-13. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025

- Gray T., Strickland S., Pooranawattanakul S., Li W., Campbell P., Jones G. et al. What are the concerns and goals of women attending a urogynaecology clinic? Content analysis of free-text data from an electronic pelvic floor assessment questionnaire (ePAQ-PF). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019; 30(1): 33-41. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3697-0

- Cichowski S., Grzybowska M. E., Halder G. E., Jansen S., Gold D., Espuña M. et al. International Urogynecology Consultation: Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROs) use in the evaluation of patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022; 33(10): 2603-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05315-1

- Безменко А.А., Захаров И.С., Беженарь В.Ф., Староверова А.С., Баграмян Э.А., Иванова О.А., Капитанова М.В. Анатомо-функциональные особенности тазового дна женщин в различные возрастные периоды. Акушерство и гинекология. 2025; 6: 131-8. [Bezmenko A.A., Zakharov I.S., Bezhenar V.F., Staroverova A.S., Bagramyan E.A., Ivanova O.A., Kapitanova M.V. Anatomical and functional characteristics of the pelvic floor in women of various age groups. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2025; (6): 131-8 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2025.101

- Tegerstedt G., Miedel A., Maehle-Schmidt M., Nyren O., Hammarström M. A short-form questionnaire identified genital organ prolapse. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005; 58(1): 41-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.008

- Collins S.A., O'Shea M., Dykes N., Ramm O., Edenfield A., Shek K.L. et al. International Urogynecological Consultation: clinical definition of pelvic organ prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021; 32(8): 2011-19. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04875-y

- Hong C.X., Nandikanti L., Shrosbree B., Delancey J.O., Chen L. Variations in structural support site failure patterns by prolapse size on stress 3D MRI. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023; 34(8): 1923-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05482-9

- Маринкин И.О., Ракитин Ф.А., Волчек А.В., Солуянов М.Ю., Кулешов В.М., Макаров К.Ю., Соколова Т.М., Нимаев В.В., Айдагулова С.В. Проявления недифференцированной дисплазии соединительной ткани и прогнозирование рецидивов при хирургической коррекции переднего пролапса тазовых органов у женщин. Акушерство и гинекология. 2024; 12: 70-9. [Marinkin I.O., Rakitin F.A., Volchek A.V., Soluyanov M.Yu., Kuleshov V.M., Makarov K.Yu., Sokolova T.M., Nimaev V.V., Aidagulova S.V. Manifestations of undifferentiated connective tissue dysplasia and prediction of recurrence after surgical correction of anterior pelvic organ prolapse in women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024; (12): 70-9 (in Russian)]. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2024.208

Received 11.06.2025

Accepted 03.07.2025

About the Authors

Ekaterina D. Dubinskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia,8 Miklukho-Maklaya str., Moscow, 117198, Russia, +7(903)117-55-58, eka-dubinskaya@yandex.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8311-0381

Alexander S. Gasparov, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Professor at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology, Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University

of Russia, 8 Miklukho-Maklaya str., Moscow, 117198, Russia, +7(985)776-77-78, 13513520@mail.ru, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6301-1880

Elizaveta N. Matskevich, Teaching Assistant at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine, Faculty of Postgraduate Education, Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, 5-2 General Antonov str., Moscow, 117342, Russia, +7(911)176-66-94, liza151196chik@mail.ru,

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3315-7408

Corresponding author: Ekaterina D. Dubinskaya, eka-dubinskaya@yandex.ru