Social and demographic predictors of postpartum depression in women in Slovakia

Postpartum depression can negatively affect the overall quality of life in mothers and child’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral development. Objective: Estimation of the prevalence of postpartum depression and the study of relationship between the risk of postpartum depression and socio-demographic factors in women in Slovakia. Materials and methods: A randomized study of newborns’ mothers (n=584; the mean age 30.9 (4.8) years) was conducted in two University maternity hospitals in Slovakia from 2019 to 2020. The first data of the study were obtained at baseline level (2–4 days after childbirth, stage I), and the next data were obtained from the subsequent follow-up (6–8 weeks after childbirth, stage II). Depression symptoms were measured using Slovakia‘s version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Moreover, some issues in the study were dedicated to detection of social and demographic risk. Threshold value 10 and higher indicated a high risk for depression symptoms. Multiple logistic regression model was used for statistical analysis. Results: Prevalence of postpartum depression was 12.74% at stage I, and 22.05% at stage II. Regression analysis with regard to social and demographic factors showed that i) primiparous women; ii) unemployment before pregnancy; and iii) insufficient financial security were statistically significantly associated with the symptoms of postpartum depression in the first days after childbirth (p<0.05). Six weeks after childbirth, the relationship between postpartum depression and i) insufficient financial security; ii) unemployment in the postpartum period (р<0.05) was identified. Conclusion: Among puerperant women, significant differences in the level of depression were identified with respect to the soсial and demographic factors. These factors need to be further explored and should be taken into account when planning intervention and prevention strategies for women.Kelčíková S., Mazúchová L., Maskalová E., Malinovská N.

Keywords

Regarding physiological conditions, the postpartum period in a period of stress for a female organism, which undergoes both the biological and psychosocial changes. Any disease in mother complicates this condition [1]. Postpartum depression (PPD) occurs in 10–20% of puerperant women, can have a significant negative impact impact on mother's total quality of life and prevent from positive experience of early motherhood [2, 3]. This is a common problem in women of reproductive age in the postpartum period up to 6 weeks after childbirth; but, if not recognized or undiagnosed, it becomes a significant burden for public health [4]. Nevertheless, PPD remains often undiagnosed and uncured [2, 3]. Several risk factors associated with development of PPD have been studied, including health factors (positive maternal mental health anamnesis before pregnancy, complications during pregnancy, perinatal losses in history, etc.) and psychosocial factors (low social support, psychosocial stressors, unwanted pregnancy, child abuse and domestic violence, low educational attainment, financial hardship, low birth satisfaction) [5–8]. It is difficult to determine the exact reason for development of PPD. Some researchers identified a number of risk factors influencing the occurrence and progression of PPD. In addition to health condition, psychosocial factors, social stressors, such as financial stress/injury/low income, low socioeconomic status [9–11], including unplanned pregnancy [8, 12–16] are also considered to be risk factors for PPD occurrence. Also, it has been shown that parity has a significant impact on PPD [17]. It has been reported that high parity is protective factor for PPD [18].

PPD is a serious health problem facing women all over the world. The adverse health outcomes for mothers and their families are well documented. For this reason, it is important to identify women at risk of PPD and thereby contribute to significant improvements in health care. In our study, we concentrated on occurrence of risk factors for PPD in terms of socio-demographic variables (financial position, education, marital status, loneliness, employment, parity, age). It is believed that many of these factors influence the development of PDD. Also, we sought to assess prognostic value of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) by monitoring the women on days 2 and 4 after childbirth, and then on week 6–8 after childbirth. To our knowledge, our study is a first prospective, cross-sectional study in the Slovak Republic, which investigates socio-demographic predictors of postpartum depression.

The purpose of our study was to estimate the prevalence of PPD and to identify association between socio-demographic factors and postnatal course of depressive symptoms in women in the Slovak Republic.

Materials and methods

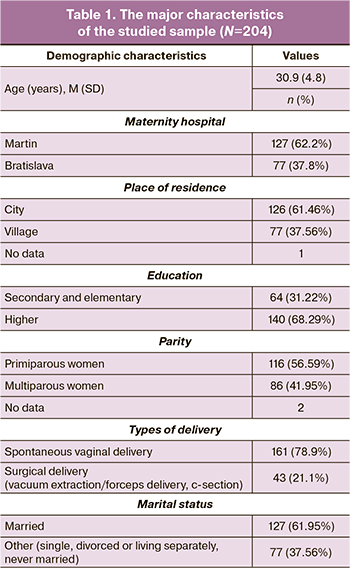

The design of this study is a randomized controlled study. The data were obtained two times: first, on days 2 and 4 of maternity hospital stay (the average length of hospital stay of parturient women in the Slovak Republic is 4 days), the questionnaire was distributed among the women personally by the obstetrician (stage I); secondly, the participants received the questionnaire by E-mail (stage II). The questionnaire was distributed in two University hospitals in Martin and Bratislava in Slovakia. The following inclusive criteria were defined for the sample: the women in the postpartum period within 6 weeks after childbirth, who gave birth to live born infants, were ready to participate in the study and signed informed consent. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and signed consent forms before answering the questionnaire. At stage I, the group of respondents consisted of 584 women after childbirth. The total percentage of filled in questionnaires was 82.3% (481/584). Among 584 women in the initial sample, 204 were investigated at stage II between weeks 6 and 8 after childbirth (the mean age was 30.9 (4.8) years; the age range was 20 – 44 years), and these women were included in the analysis. At stage II, the total number and percentage of filled in questionnaires was 71/204 (34,9%). The detailed characteristic of the studied sample is shown in Table 1.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which was initially developed by J. L. Cox, J. M. Holden and R. Sagovsky [19], in the Slovakia‘s version was added by questions, directed to identify socio-demographic variables (age, maternity, marital status, education level, residence, employment, income level, financial situation), which were used to measure PPD symptoms at stage I and II. EPDS is a self-assessment 10-item questionnaire containing questions about the emotional state of the respondent for the recent 7 days, and each item refers to the general symptoms of depression (estimated by scores 0-1-2-3). The total score ranges from 0 to 30 points. According to EPDS Manual, second edition (2014), various threshold values were used to assess depression risk. In our study, a score ≥10 points was chosen as an acceptable limit for the research purpose. The respondents with scores ≥10 points (first assessment) were identified as having a risk of depression, and those, who had scores <10 points, were identified as having no risk of depression. The respondents with EPDS scores ≥10 points in the second assessment were considered to be at risk of PPD regardless of the result of the first assessment. The obtained variable was based on the presence PPD (which was defined as a result of EPDS ≥10 points) within the first and the second months after childbirth. EPDS is and instrument for screening, and women with scores higher than threshold scores of 13 or 10 points, who were identified as being at a high risk of PPD were referred to mental health specialist for further assessment. The approval to use EPDS was obtained from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (UK). EPDS was translated into the Slovak language by reverse translation. In our study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency (reliability) was 0.84 at stage I, and 0.88 at stage II. The approved EPDS is widely used in several countries, and its psychometric properties proved to be useful [20].

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin (No. EK 36/2018) (the Slovak Republik). All participants were fully informed about the character and the purpose of the study, as well as about the details of participation. The data were collected anonymously, and all participants agreed to participate in the study and signed informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Multivariate logistic regression was used to mode the relationship between response (dichotomous scoring of EPDS) and socio-demographic variables. The vast majority of predictors were categorical variables that were included in the regression model as dummy variables. As a result, the number of predictors was higher than the number of observations, and the full model of logistic regression could not be included in the data. To pre-select important predictors, we used machine learning technique – Random Forest algorithm with selection of nested cross-validation function and the chart depth as a critical function. The important default predictors entered logistic regression to evaluate their statistical significance. Odds ratio was used for quantitative assessment of risk. The results at p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using R version 3.5.2, R Core Team (2018).

Results

The major demographic characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 1. Out of total number of women (n=584), 204 (34.93%) were observed during the second month after childbirth. The sample included 204 respondents in the postpartum period (days 2 and 4 after childbirth) and (6–8 weeks after childbirth). The mean age of participants was 30.9 (4.8) years. The age range was 20–44 years. More than half of women 127/204 (62.2%) gave birth in the University clinic in Martin. Most women 140/204 (68.29%) had a higher education, and 64/204 (31.2%) women had secondary or primary education. Regarding the parity, the study group consisted of 116/204 (56.59%) primiparous and 86/204 (41.95%) multiparous mothers. Most women 161/204 (78.9%) had spontaneous vaginal delivery, and 43/204 (21.1%) women had surgical delivery (vacuum extraction/forceps delivery, c-section). Regarding marital status, 127/204 (61.95%) women were married.

Prevalence of postpartum depression

EPDS score ≥10 points was in 26/204 (12.74%) women in the first days after childbirth, and a high risk of PPD was detected in 45/204 (22.05%) women in 6 weeks after childbirth.

The factors associated with PPD in the first days after childbirth

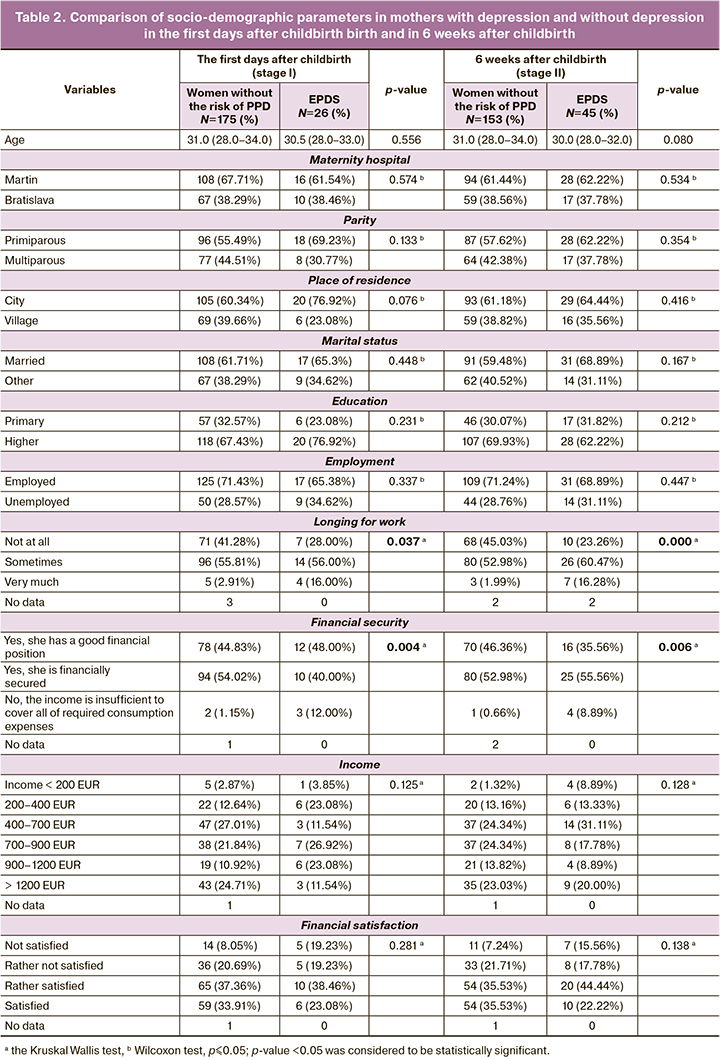

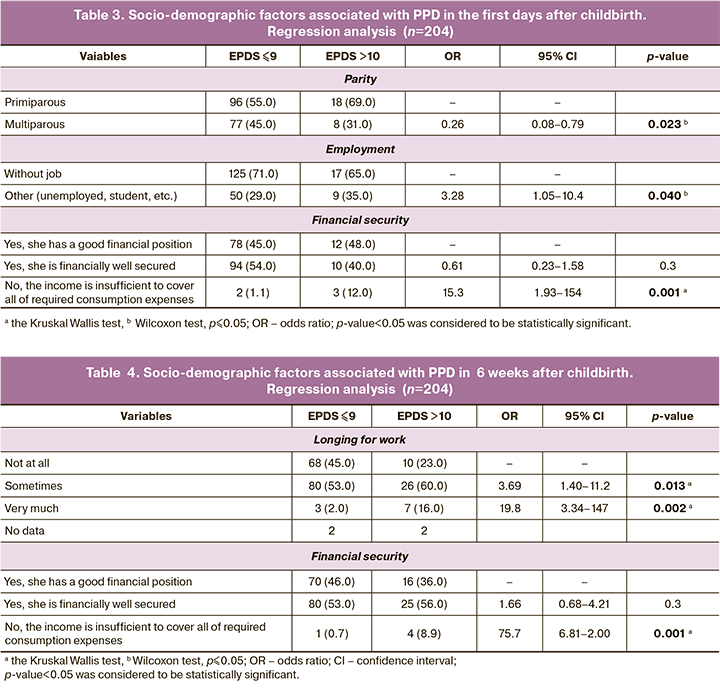

The analysis found several socio-demographic factors, which could be associated with PPD, such as insufficient financial security (Table 2, 3). Regression analysis showed that independent variables were associated with development of PPD. The results of analysis are shown in Table 4. In the first days after giving birth, the following predictors of PPD were identified: primiparous women, unemployment before pregnancy and insufficient financial security (р<0.05).

The factors associated with PPD six weeks after childbirth

Also, the analysis detected some factors associated with PPD in 6 weeks after childbirth (Table 2, 3). Regarding risk factors, which were registered in the first days after giving birth, such factors as parity and employment were not present before 6 weeks after childbirth. However, in addition to financial security, another factor “without job” was analyzed. Regression analysis showed that independent variables were associated with development of PPD in 6 weeks after childbirth. The results are shown in Table 4. In six weeks after giving birth, the following predictors of PPD were identified: without job in the postpartum period and insufficient financial security (р<0.05).

Discussion

We investigated association between socio-demographic factors and postpartum depressive symptoms in female residents of Slovakia. Our study was based on using the EPDS questionnaire and the questions developed by us with regard to risk factors.

The study showed that changing socio-demographic variables, such as unemployment before pregnancy, inadequate social security, primiparous mothers, significantly predict a high level of PPD symptoms on days 2–4 after childbirth. Significantly increased level of PPD symptoms on weeks 6–8 after childbirth was associated with insufficient material security, and one more factor “without job in the postpartum period” was added. Some characteristics of the group suggested or most likely confirmed a protective role of the factors, such as higher age and higher education, and this suggestion was consistent with the study [21].

The birth of a child is a serious change in woman's life and involves new problems and often requires lifestyle changes and taking on a new role. This stressful situation and depression symptoms may occur, if a woman fails to adapt to this new situation. The depressed person is usually unaware of the need for change and insists on the old rules of behavior - usually it may be a change that she also experiences as a loss (for example, the loss of freedom that a childless woman has). This is especially important for primiparous mothers, because they are emotionally more vulnerable than mothers with many children [22]. In our study, postpartum depression symptoms occurred less often in multiparous mothers (OR=0.26 (0.08–0.79), р=0.023) (Table 3). The results obtained in our study are consistent with the results of other researches [8, 23]. Nevertheless, some studies suggested that the risk of PPD is higher in multiparous mothers [24–26]. Some researchers reported that multiparous women might have higher EPDS scores due to the greater burden of childcare, as well as increased psychosocial stress [26]. The findings of our study emphasize the importance of paying great attention to primiparous mothers due to their mental health and potential risk of developing PPD.

We found, that PPD develops 3.28 times more often in unemployed women and students versus the women, who worked full time before pregnancy. Our findings are consistent with the results of other studies [11, 27, 28]. Moreover, some authors suggest that unemployment, in particular, can have a negative effect on woman's mental health due to financial problems and worrying about her child’s future [29].

Maternity leave is usually a period of time, which is necessary for a woman to rest and recover after pregnancy and childbirth, when she performs a full range of childcare. After giving birth, the woman may experience initial anxiety and fear that she will not be able to care for her baby, or will become less attractive after pregnancy. All this can make some women think that they should return to work in the sense that they feel themselves longing for work. The feeling that a woman does not have a job may also be due to the fact that having maternity leave, she may be concerned about the risk to lose work-related professional skills, and as a result, to lose her job. We found, that women who reported that they were longing for work in 6 weeks after childbirth, had PPD stress 20 time more often than women, who were partially longing for work, or those, who had no need to work. However, there are no studies, that confirmed or denied our suggestions. One of the studies found that the women who took maternity leave, had significantly low scores for depression in 6, 12 weeks and 6 months after childbirth versus those, who returned to work during the study period. This confirms the suggestion that with longer length of maternity leave the risk for PPD is lower [30]. In Slovakia, the length of paid maternity leave for pregnancy and birth is 34 weeks, and when the woman gives birth to twins or several children, maternity leave is extended up to 43 weeks. After the end of maternity leave, many Slovak women stay home and take parental leave until the child is three years old. It is common, that they continue their subsequent parental leave and quit the job for several years. Returning to work after a long period of time is a huge burden for women’s mental health. Thus, this fact may stimulate further research to study PPD among the group of women, who are excluded from work activity due to childcare.

In our study, the prevalence of PPD immediately after childbirth (stage I) was 12.74% and thus, it was lower than the prevalence of PPD reported in a similar study [31]. Despite the fact, that according to published data, depressive symptoms occur relatively early in the postpartum period, our data showed that they rarely occur. The prevalence of PPD in 6 weeks after childbirth (stage II) was 22.05%. Thus, the prevalence was higher than in other studies [8, 32]. Although the prevalence of PPD symptoms is similar across cultures, risk factors vary considerably. Many factors under investigation in this study were associated with PPD in the postpartum period and in 6 weeks after childbirth. However, some authors suggest that prevalence of PPD is highly variable, and differs among different cultures [4, 33].

In the context of the results, we can report that our study demonstrates the importance of PRD screening using ESHR as a research tool that can be used by healthcare workers. This study highlights the importance of introduction of PPD screening tools as a routine part of standard care for women to determine the risk of PPD during pregnancy, postpartum period, and in six weeks after giving birth. Some authors [34] confirm that the use of phychometric tools for nursing care is not a commonly accepted standard for assessment of the patient’s condition, but their use is an important determinant of healthcare quality. Screening tools help to identify the risk and severity of PPD, avoid or eliminate it by evidence-based early preventive interventions. The results of our study may help healthcare workers to pay more attention to the identified socio-demographic predictors of PPD and schedule appropriate interventions and preventive strategies for women both at the healthcare level and at the level of the state. Given serious biological and psychosocial consequences of the PDP on women's health, child development and whole family functioning, which have a negative impact on population health, the efforts should mainly focus on childcare (parental skills training) and strengthening mental health of women and should be taken into account at the political level. In the context of intervention program, which is aimed to improve social and working conditions, financial security of women during this period of life, can also be important, as well as creation of conditions for preventive programs, legislative provision of postpartum care (for example, to support and develop outpatient care, to help in solution of various social problems) and labor policy. It is also necessary to improve the mutual interdisciplinary communication between the employees in practical work when solving PRD issues (cooperation between the gynecologist, therapist, pediatrician, community midwife, psychiatrist and social worker). All these professionals perform assessment of health and its components from their own point of view. Therefore, the holistic concept of health promotion can be achieved by combining their views with help and support options. Regular regional meetings of professional representatives is considered to be expedient [35].

The use of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale is one of the strengths of this study. It helped to compare the results with other similar studies and interpret the results in the international context. The study contributes to a better understanding of PPD and socio-demographic factors in our environment, since this type of studies are rarely carried out in Slovakia.

Limitations of the study

The results and conclusions of our study should be considered in view of its limitations, including a high level of non-participation in the subsequent observation (stage II), which could be due to difference in the process of data collection. At stage I, the data were collected personally, and this contributed to a higher response rate compared to data collection by E-mail at subsequent stage II. Despite some limitations, we believe that the results of the study were constructive and convincing.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest the need to introduce more comprehensive care into clinical practice and in the area of psychosocial screening with focus on primiparous women, financial security of the family and women's work, which can influence the transition of women to motherhood. It is necessary to focus on a detailed study of socio-demographic factors associated with PPD. This could be useful for the healthcare system in Slovakia. We consider that thorough investigation of these factors at the community level is important. The use of EPDS during pregnancy, as well as in the first week after childbirth is a useful tool to identify women at risk of PPD. Cooperation of health professionals (gynecologist, physician, general practitioner for adults, pediatrician, community midwife, psychiatrist, etc.) is necessary within the framework of prevention, support or help for women. Risk factors for PPD need to be further explored and should be taken into account when planning interventions and prevention strategies for women.

References

- Izáková Ľ. Duševné zdravie počas tehotenstva a po pôrode. Psychiatria pre prax. 2015; 16: 18-20. Psychiatr. praxi. 2013; 14(4): 161-3.

- Woody C.A., Ferrari A.J., Siskind D.J., Whiteford H.A., Harris M.G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017; 219: 86-92. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003.

- Underwood L., Waldie K., D’Souza S., Peterson E.R., Morton S. A review of longitudinal studies on antenatal and postnatal depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2016; 19(5): 711-20. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0629-1.

- Desai N.D., Mehta R.Y., Ganjiwale J. Study of prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression. Natl. J. Med. Res. 2012; 2(2): 194-8.

- Brummelte S., Galea L.A. Postpartum depression: etiology, treatment and consequences for maternal care. Horm. Behav. 2016; 77: 153-66.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.08.008.

- Hutchens B.F., Kearney J.J. Risk factors for postpartum depression: an umbrella review. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2020; 65(1): 96-108.https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13067.

- Bell A.F., Andersson E. The birth experience and women's postnatal depression: a systematic review. Midwifery. 2016; 39: 112-23. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.04.014.

- Fiala A., Švancara J., Klánová J., Kašpárek T. Sociodemographic and delivery risk factors for developing postpartum depression in a sample of 3233 mothers from the Czech ELSPAC study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017; 17(1): 104.https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1261-y.

- Hill A.J., Hettinger C.R. The intersectionality of race, postpartum depression, and financial stress. Concordia St. Paul Blog & News Updates. 2019; 5(2): 1-9. Available at: https://online.csp.edu/blog/forensic-scholars-today/race-postpartum-depression-ppd-financial-stress/

- Qobadi M., Collier C., Zhang L. The effect of stressful life events on postpartum depression: findings from the 2009-2011 mississippi pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Matern. Child Health J. 2016; 20(Suppl. 1): 164-72.https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2028-7.

- Goyal D., Gay C., Lee K.A. How much does low socioeconomic status increase the risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms in first-time mothers? Womens Health Issues. 2010; 20(2): 96-104. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2009.11.003.

- Faisal-Cury A., Menezes P.R., Quayle J., Matijasevich A. Unplanned pregnancy and risk of maternal depression: secondary data analysis from a prospective pregnancy cohort. Psychol. Health Med. 2017; 22(1): 65-74.https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2016.1153678.

- Steinberg J.R., Rubin L.R. Psychological aspects of contraception, unintended pregnancy, and abortion. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2014; 1(1):239-47. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2372732214549328.

- Zubaran C., Foresti K. Investigating quality of life and depressive symptoms in the postpartum period. Women Birth. 2011; 24(1): 10-6.https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2010.05.002.

- Abbasi S., Chuang Ch., Dagher R., Zhu J., Kjerulff K. Unintended pregnancy and postpartum depression among first-time mothers. J. Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013; 22(5): 412-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.3926.

- Brito C.N., Alves S.V., Ludermir A.B., Araújo T.V. Postpartum depression among women with unintended pregnancy. Rev. Saude Publica. 2015; 49: 33.https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0034-8910.2015049005257.

- Martínez-Galiano J.M., Hernández-Martínez A., Rodríguez-Almagro J., Delgado-Rodríguez M., Gómez-Salgado J. Relationship between parity and the problems that appear in the postpartum period. Sci. Rep. 2019; 9(1): 11763.https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47881-3.

- Staehelin K., Kurth E., Schindler Ch., Schmid M., Zem E. Predictors of early postpartum mental distress in mothers with midwifery home care – results from a nested case-control study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2013;143: w13862.https://dx.doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13862.

- Cox J.L., Holden J.M., Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression.Development of the 10-item edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1987; 150: 782-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

- Cox J.L., Holden J.M., Henshaw C. Perinatal Mental Health. The Edinburgh Postanatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Manual. 2nd ed. London: The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

- Izáková Ľ., Borovská M., Baloghová B., Krištúfková A. Výskyt depresívnych príznakov v popôrodnom období. Psychiatr. praxi. 2013; 14(1): 26-9.

- Smorti M., Ponti L., Pancetti F. A comprehensive analysis of post-partum depression risk factors: the role of socio-demographic, individual, relational, and delivery characteristics. Front. Public Health. 2019; 7: 295.https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00295.

- Nakamura Y., Okada T., Morikawa M., Yamauchi A., Sato M., Ando M. et al. Perinatal depression and anxiety of primipara is higher than that of multipara in Japanese women. Sci. Rep. 2020; 10(1): 17060. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74088-8.

- Qandil S., Jabr S., Wagler S., Collin S.M. Postpartum depression in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: a longitudinal study in Bethlehem. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016; 16(1): 375. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1155-x.

- Roomruangwong C., Withayavanitchai S., Maes M. Antenatal and postnatal risk factors of postpartum depression symptoms in Thai women: a case-control study. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2016; 10: 25-31. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2016.03.001.

- Mathisen S.E., Glavin K., Lien L., Lagerløv P. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in Argentina: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Womens Health. 2013; 5: 787-93. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S51436.

- Lewis B.A., Billing L., Schuver K., Gjerdingen D., Avery M., Marcus B.H. The relationship between employment status and depression symptomatology among women at risk for postpartum depression. Womens Health. (Lond). 2017; 13(1): 3-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1745505717708475.

- Gjerdingen D., McGovern P., Attanasio L., Johnson J.P., Kozhimannil B.K. Maternal depressive symptoms, employment, and sociala support. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2014; 27(1): 87-96. https://dx.doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.01.130126.

- Saurel-Cubizolles M.J., Romito P., Ancel P.Y., Lelong N. Unemployment and psychological distress one year after childbirth in France. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 2000; 54(3): 185-91. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.54.3.185.

- Dagher R.K., McGovern P.M., Dowd B.E. Maternity leave duration and postpartum mental and physical health: implications for leave policies. J. Health Polit. Policy Law. 2014; 39(2): 369-416. https://dx.doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2416247.

- El-Hachem C., Rohayem J., Bou Khalil R., Richa S., Kesrouani A., Gemayel R. et al. Early identification of women at risk of postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in a sample of Lebanese women. BMC Psychiatry. 2014; 14: 242. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0242-7.

- Grussu P., Quatraro R. Prevalence and risk factors for a high level of postnatal depression symptomatology in Italian women: a sample drawn from ante-natal classes. Eur. Psychiatry. 2009; 24(5): 327-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.006.

- Posmontier B., Waite R. Social energy exchange theory for postpartum depression. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2011; 22(1): 15-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1043659610387156.

- Rabinčák M., Tkáčová Ľ. Využívanie psychometrických konštruktov pre hodnotenie porúch nálady v ošetrovateľskej praxi. Zdravotnícke listy. 2019; 7(2): 22-8.

- Hendrych Lorenzová E., Boledovičová M., Kašová L. Péče komunitní porodní asistentky o šestinedělku s popoorodní depresi. Pediatr. praxi. 2016; 17(5):322-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.36290/ped.2016.072.

Received 05.07.2022

Accepted 23.09.2022

About the Authors

Simona Kelčíková, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing, Midwifery and Public health at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery, kelcikova@jfmed.uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2347-4343, Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.Lucia Mazúchová, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing and Midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery, mazuchova@jfmed.uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9363-0922, Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.

Erika Maskalová, MSN, PhD, a lecturer with the specialization on Nursing and Midwifery at Comenius University (Bratislava), Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Midwifery, maskalova@jfmed.uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2806-4586, Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.

Nora Malinovská, MA, PhD, a lecturer in Medical Latin and English for Medical Purposes at Comenius University (Bratislava),

Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Department of Foreign Languages, 00421 432633520, nora.malinovska@uniba.sk, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5334-207X,

Malá Hora 5, Martin 036 01, Slovakia.

Corresponding author: Nora Malinovská, nora.malinovska@uniba.sk

Authors’ contributions: Kelčíková S., Mazúchová L. – the concept and design of the study, material collection and processing; Maskalová E. – statistical data processing; Kelčíková S., Mazúchová L., Malinovská N. – article writing; Malinovská N. – article editing.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding: The study was carried out without any sponsorship.

Acknowledgements: The study was supported by VEGA project (Research Funding Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences) in the frames of contract No. VEGA-1/0211/19.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin (No. EK 36/2018) (Bratislava, the Slovak Republic).

Patients’Consent for Publication: The patients have signed informed consent for participation in the study and use of their data in publications.

Authors’ Data Sharing Statement: The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author after approval from the principal investigator.

For citation: Kelčíková S., Mazúchová L., Maskalová E., Malinovská N.

Social and demographic predictors of postpartum depression in women in Slovakia.

Akusherstvo i Gynecologia/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; 10: 67-75 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2022.10.67-75