Algorithms for Menopausal Hormonal Therapy In Peri- and Postmenopausal Women. Joint Position Statement of ROAG, RAM, AGE, and RAOP

Authors and developers: L.A. Ashrafyan, V.E. Balan, I.I. Baranov, Zh.E. Belaya, S.A. Bobrov, A.V. Voroncova, S.O. Dubrovina, I.E. Zazerskaya, I.A. Ilovajskaya, L.Yu. Karakhalis, O.M. Lesnyak, M.I. Mazitova, N.M. Podzolkova, A.E. Protasova, V.N. Serov, A.A. Smetnik, L.S. Sotnikova, E.A. Ulrikh, G.E. Chernukha, S.V. Yureneva.

ROAG – Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, RAM – Russian Association for Menopause, AGE-Association of Gynecologists and Endocrinologists, RAOP – Russian Association for Osteoporosis

In has been obvious from demographic data for quite a while that populations generally become older as life expectancies tend to rise everywhere [1]. These changes translate into ever larger numbers of postmenopausal women, up to 85% of them presenting with medical conditions such as vasomotor symptoms, psychoemotional or urogenital disorders, and generally being more susceptible to long-term health problems such as osteoporosis-related higher risks of femoral fracture; cardiovascular diseases; and diabetes mellitus [2].

Taken together, these risks create a comprehensive and dramatic impact not just on women’s health but more generally on their quality of life, meaning that the preservation of the quality of life as well as good health status becomes critically important not only from the purely medical but also from the socioeconomic standpoint.

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is universally recognized as the most efficacious and pathogenetically proven method for correcting climacteric disorders. Together with the fundamentally important maintenance of healthy lifestyle, it creates a firm basis for health preservation in peri- and postmenopausal women.

According to the available body of scientific knowledge, MHT helps control vasomotor symptoms in 75% of cases; decrease the femoral fracture and diabetes risks by 30%; decrease cardiovascular mortality by 12 to 54%; and is likely instrumental in additionally reducing the all-causes mortality in women aged 50-59 by 31% [2].

Only 1.3% of women aged 45-59 in the Russian Federation are current MHT users – 2.5 times lower than the average across the European Union and about one-fifth of the real need. The direct economic effect of lives saved and days of sick leave prevented is currently estimated at 6.3 billion Rubles per year, and if the share of MHT users in the target age group rises to that more characteristic of developed economies, this effect could go up 2.5 times to 15.4 billion Rubles per year [2].

The most pertinent issue related to MHT is personalization, so that efficacious symptomatic management could be part of a dynamic risks vs. benefits balancing strategy tailored to the patient’s needs and preferences, age, climacteric period, response to therapy, and comorbidities.

These basic algorithms were developed by experts with due consideration of international MHT guidelines [8, 13, 20–22, 33, 34, 36–39, 41, 47], and findings of key studies [3–7, 9–12, 14, 23–30, 35, 40, 42–50], consolidated and transformed into practical guidance, which is to be published in two stages:

- In Stage 1, the current algorithms describe the general principles for establishing the right dosage for MHT starters and ongoing users; managing MHT-related bleeding; and switching from combined oral contraceptives to MHT regimen;

- In Stage 2, a broader paper will be published, with further algorithms for the diagnosis and therapy of early ovarian insufficiency, understanding MHT influence on the cognitive function and metabolic syndrome, breast safety for MHT users, and managing the levels of androgens in peri- and postmenopausal women.

These Algorithms are designed as an everyday practical tool for clinicians seeking effective MHT personalization to successfully support patients with menopausal symptoms and make a personal contribution to the overall national goal of well-being and prosperity.

Euestrogenemia theory as a case for the early start of MHT

According to basic studies and clinical trials, estrogens, as key regulators of metabolic pathways, are systemically important for homeostasis. The ubiquitous nature of estrogen receptors (ERs), with over 3,600 estrogen pathways confirmed so far, is a fundamental concept of the theory of life-long euestrogenemia [3] premised on the need for maintaining sufficient levels of estrogens for the optimal ER functioning.

While ERs are known to respond well to exogenous estrogens administered after short-term abstinence, longer-term hypoestrogenemia and corresponding ER inactivity may result in the loss of function, associated with lower chances for successful “late re-estrogenization” [4].

The concept of euestrogenemia is especially thought-provoking in the light of the latest research findings on changes in vasomotor regulation and body composition vis-à-vis the onset – or progress – of osteoporosis and other metabolic conditions setting the stage for a broader set of age-related diseases. One thing that definitely deserves a close look is to what extent the timing of MHT onset should be driven by the residual opportunity to create protective effects in ER-expressing organs and tissues and thus lay the groundwork for the healthy longevity of the modern woman [5].

According to a hypothesis presented by Miller et al. and generally consistent with the concept of euestrogenemia, understanding the menopausal hormonal changes may unmask personal differences in the woman’s autonomic neurovascular control mechanisms, which may have a genetic basis or may be acquired across the life span, and were found to be consistent with the variability of the clinical manifestations of aging observed in women [6].

Studies performed in Australia, the UK, and the U.S. helped identify four consistent patterns of vasomotor disturbances in female populations diverse enough to suggest that these patterns are unlikely to be solely explained by socioeconomic or cultural factors, and, therefore, must be of biological nature, such as genetic variations changing the way estrogens are secreted and their pathways activated, or regulating catecholaminergic pathways in the central neural system, responsible for the clinical manifestations of a “hot flush” [7].

As estrogen levels go gradually down in perimenopause, a woman may present with early signs of reproductive system “ageing,” such as hot flushes, nocturnal sweating, psychoemotional disorders, and changes in the body composition and proportions. While the menstrual cycle may still be regular enough, these signs should be considered possible markers of fading ovarian function; they also considerably reduce the quality of life.

MHT is considered the most efficacious treatment of vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms in women with no contraindications [8]. As we have said before, estrogens are not just important for the reproductive function; as pleiotropic hormones, according to the concept of euestrogenemia, they project multiple effects on most organs and tissues. Therefore, MHT, if started before the closure of the “therapeutic window of opportunity,” may help prevent many ageing-related conditions.

Estrogen effects on arteries were found to vary with the stage of reproductive life and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis progression [9]. Trials such as ELITE and MESA have confirmed positive cardiovascular effects of timely MHT onset [10, 11]. There is also convincing evidence of comprehensive benefits in women starting MHT in a timely manner (before the age of 60 or earlier than 10 years after the menopause) [11–13], which underscores the obvious utility of MHT.

To evaluate a woman’s “window of opportunity” for starting MHT, two key factors are to be taken into account: age and the time past menopause. Women aged under 60 and/or less than 10 years past menopause are considered optimal candidates for MHT onset [8].

Early-onset MHT may be an option in 45-plus women who are amenorrheic but present with vasomotor symptoms. Women under 45, presenting with oligo- or amenorrhea, with or without vasomotor symptoms, should undergo a set of hormonal tests: FSH twice four to six weeks between the tests; TTH; and prolactin. MHT may be considered at FSH levels >25 IE/l [14].

Timing the onset of MHT; switching from cyclical to continuous regimen

In climacteric disorders, personalized approach is key. Following are the principles of MHT tailoring, consistent with the modern concept of personalization [8].

1. Consider the safety profiles of the MHT regimen components.

2. Individualize the regimen with due consideration for the risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, breast cancer, postmenopausal osteoporosis, and comorbidities:

- reaching the minimal efficacious dose;

- determining the preferred administration route for the MHT regimen;

- choosing the regimen on the basis of patient’s age, stage of reproductive life (as assessed with STRAW +10) and preferences.

MHT usage should consider a possibility for correcting the dose at the right stage of reproductive life, age, efficacy, and tolerability, with the aim of:

1. effectively controlling the climacteric symptoms;

2. reducing / deferring long-term consequences of estrogen deficiency;

3. reducing possible risks and adverse events from therapy.

|

Doctors need to address the following clinical issues as they stratify treatment tactics for the patient’s stage of reproductive life:

These algorithms apply to the most prevalent clinical cases and do not necessarily cover all possible multi-morbid conditions. |

Women with intact uterus should receive combined hormonal therapy with a gestagenic as well as estrogenic component, the gestagen required to protect the endometrium from the estrogenic proliferative effects, thus preventing the risk of endometrial hyperplasia. Women after hysterectomy should get continuous estrogen-only therapy (except women awaiting surgery for endometriosis, in which case the preferred choice is combined estrogen-gestagen MHT, or tibolone).

As of this writing, the following combinations of estrogens and gestagens are approved in the Russian Federation for the therapy of climacteric disorders in women with intact uterus [15]:

- Cyclical regimen combinations: 2 mg Estradiol Valerate + 0.15 mg Levonorgestrel; 2 mg or 1 mg Estradiol + 10 mg Dydrogesterone; 2 mg Estradiol Valerate + 10 mg Medroxiprogesterone Acetate; 2 mg Estradiol Valerate + 2 mg Cyproterone Acetate;

- Continuous regimen combinations: 1 mg or 0.5 mg Estradiol + 5 mg or 2.5 mg Dydrogesterone, respectively; 1 mg or 0.5 mg Estradiol + 2 mg or 0.25 mg Drospirenone, respectively.

Table 1 presents an example of MHT personalization for women with intact uterus with the available combinations of Estradiol and Dydrogesterone, to demonstrate the management algorithm for patients at various climacteric stages. This combination has the broadest range of dosages and administration modalities, making it possible to change regimens and doses while staying with the same components, which improves compliance. The algorithm is equally applicable to all medicines listed above.

|

Table 1. Available Estradiol / Dydrogesterone combinations |

||

|

Cyclical MHT regimen [16, 17] |

||

|

Estradiol dosage |

1 mg Estradiol 10 mg Dydrogesterone |

Days 1-28 Days 15-28 |

|

Low |

||

|

Standard |

2 mg Estradiol 10 mg Dydrogesterone |

Days 1-28 Days 15-28 |

|

Continuous MHT regimen [18, 19] |

||

|

Low |

1 mg Estradiol 5 mg Dydrogesterone |

|

|

Ultra-low |

0.5 mg Estradiol 2.5 mg Dydrogesterone |

|

Choice of therapy

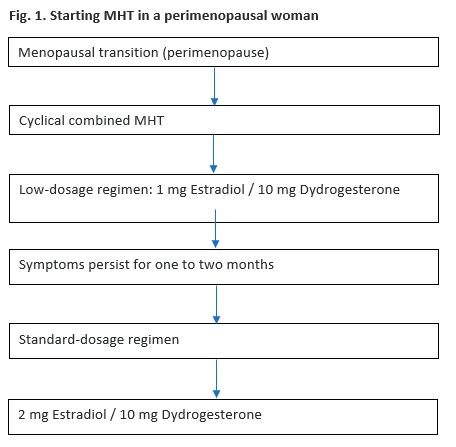

Starting MHT in a perimenopausal woman

The overall recommendation for perimenopausal women is to start with a cyclical low-dosage regimen, for example, 1 mg Estradiol / 10 mg Dydrogesterone. The response should be assessed on an individual basis in one to two months, with possible increase of the dosage of Estradiol, switching to the 2 mg Estradiol drug, if the symptoms persist (Figure 1).

In patients with early (age 40-44) and premature (under 40) menopause, or in patients with premature ovarian insufficiency, MHT should start with the standard cyclical regimen of the oral 2 mg Estradiol / 10 mg Dydrogesterone drug. In poor responders, as assessed one to two months after the start of MHT, a high-dosage cyclical regimen of 4 mg Estradiol / 20 mg Dydrogesterone per day may be considered [20].

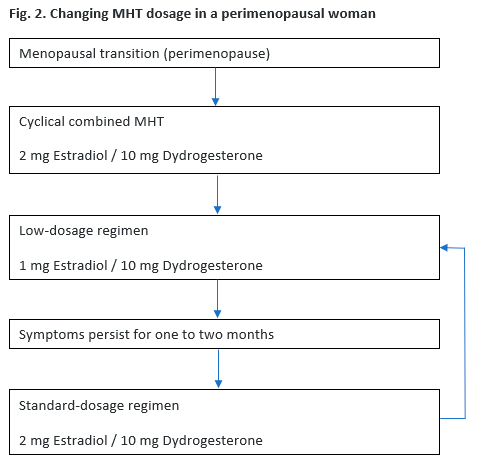

The clinical response in MHT standard-dosage regimen (2 mg Estradiol / 10 mg Dydrogesterone) users, including those who have switched from the low-dosage regimen (1 mg Estradiol / 10 mg Dydrogesterone), should be assessed after one to two months of therapy as efficacy (reduction in / disappearance of vasomotor symptoms; improved sleep and mood, etc.) vs. tolerability (edema, mastodynia etc.).

If estrogen-dosage-related adverse MHT effects such as edema or mastodynia are found in the course of such an assessment, lowering the estrogen dose should be considered with the general aim of using the minimal effective dose, such as switching to the low-dosage cyclical MHT (1 mg Estradiol / 10 mg Dydrogesterone) (Figure 2).

The following cyclical combined MHT users may need switching to continuous combined MHT:

Women who started MHT after the age of 50 – after using low-dosage cyclical MHT for one to two years;

Women who started MHT before the age of 50 – as the woman progresses to the average age of menopause (51-52);

Women who experience changes in their menstrual-like bleeding (MLB) – as two consecutive cycles produce either minor spotting or no bleeding;

Women who wish to end menstrual-like episodes – after using low-dosage cyclical MHT (1 mg Estradiol / 10 mg Dydrogesterone) for at least 12 months (to prevent breakthrough bleeding) [21, 22].

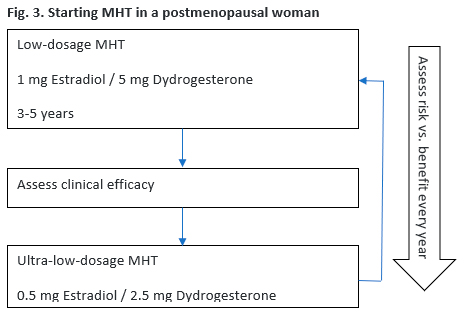

Starting MHT in a postmenopausal woman

The overall recommendation for postmenopausal women (12 months or more after the last menstrual episode) is to use continuous combined MHT, starting with the low-dosage regimen with 1 mg of Estradiol (for example, 1 mg Estradiol / 5 mg Dydrogesterone). Such an MHT user should undergo annual examination to assess the risks vs. benefits of the ongoing therapy.

After using low-dosage continuous combined MHT for three to five years, switching to the ultra-low-dosage continuous combined regimen (for example, 0.5 mg Estradiol / 2.5 mg Dydrogesterone) may be considered (Figure 3).

Postmenopausal women may start using MHT with the ultra-low-dose. However, it should be borne in mind that ultra-low-dose MHT is not approved for the prevention of osteoporosis [21, 22]. Another important consideration should be that in women aged under 55, less than five years past menopause and having BMI > 30 kg/m2, ultra-low-dose MHT may not be sufficient for the full clinical efficacy. Thus, in one to two months switching to low-dose MHT (for example, 1 mg Estradiol / 5 mg Dydrogesterone) may be considered [23] (Fig. 4). Such MHT users should undergo annual examination to assess the risks vs. benefits of the ongoing therapy, with the available options of continuing therapy, switching the patient to the ultra-low-dose regimen, or terminate therapy. With such an assessment, the term of therapy is not limited and is to be determined on an individual basis, considering the treatment goals and efficacy vs. tolerability (Fig. 5).

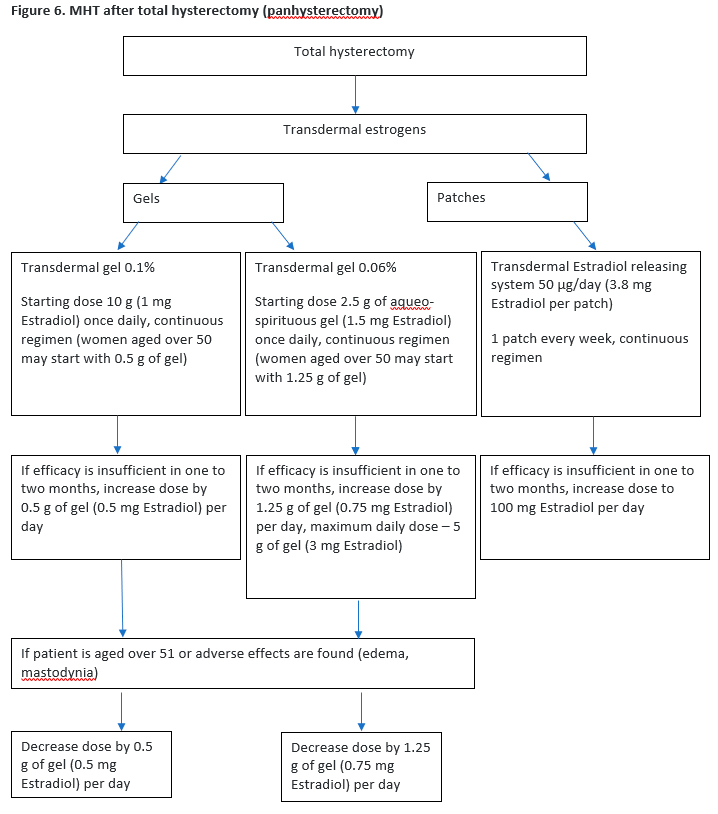

MHT after total hysterectomy

In women aged under 51 (mean age of menopause in Russia) after total hysterectomy (panhysterectomy), estrogen-only hormonal therapy administered orally, or transdermally as patch or gel would be sufficient to control climacteric symptoms or risk of osteoporosis (except women presenting with endometriosis, in which cases the preferred choice is combined estrogen-gestagen MHT, or tibolone).

As of this writing, the following estrogen-only medicines are approved in the Russian Federation [15]:

- Oral: 2 mg Estradiol Valerate;

- Transdermal: Transdermal Estradiol releasing system 50 µg/day (3.9 mg Estradiol Hemihydrate, corresponding to 3.8 mg Estradiol, per patch), Estradiol Hemihydrate cutaneous gel 0.1% (0.5 mg Estradiol, or 1 mg Estradiol, per packet), Estradiol Hemihydrate aqueo-spirituous cutaneous gel 0.06% (1.5 mg Estradiol per 2.5 g of gel).

See Figure 6 for an example of an algorithm of transdermal climacteric symptoms therapy in women after total hysterectomy.

Managing bleeding in MHT users

Postmenopausal uterine bleeding (PMB) is defined as uterine bleeding occurring after more than one year of persistent amenorrhea resulting from the loss of ovarian activity [24].

PMB etiology

While intrauterine pathology is still the most prevalent cause of PMB, such bleeding may also occur as a result of cervical or vaginal, or non-gynecological, such as urinary or gastrointestinal, pathology. Patients presenting with PMB are at high risk of endometrial cancer, which requires urgent diagnostic follow-up. Any PMB complaint ought to be taken very seriously and addressed accordingly [25].

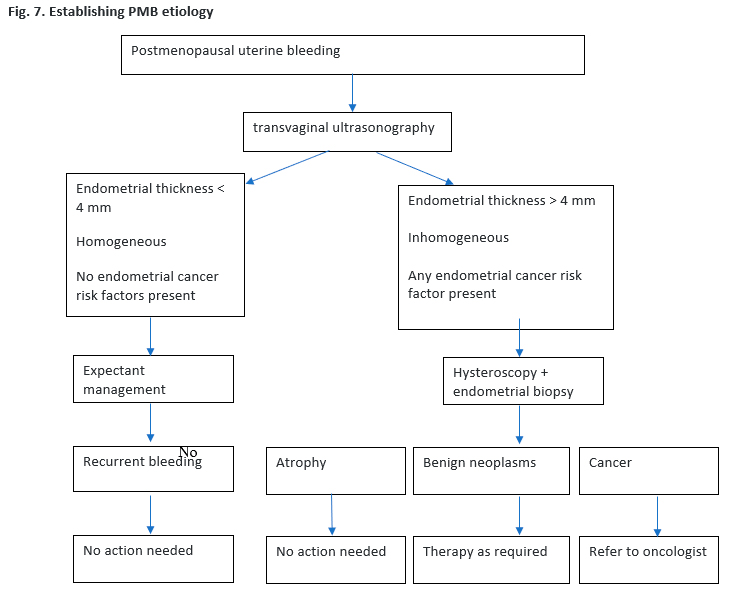

See Figure 7 for an algorithm to diagnose PMB and determine the management strategy [25].

PMB in MHT users

According to the available body of scientific knowledge, the risk of endometrial cancer in postmenopausal MHT users presenting with vaginal (breakthrough) bleeding is significantly lower than in non-users. A broad 2018 metaanalysis covering over 40,000 women found that the risk of endometrial cancer among postmenopausal MHT users was 7%, while among non-users 12% (р<0.001) [26].

This finding is confirmed by the 2020 Danish nationwide cohort study for the clinical markers of long-term endometrial cancer risk, in which over 43,000 women presenting with PMB were followed up. The risk of developing endometrial cancer for MHT users was 3.2% within one year and 3.6% within five years after PMB; for non-users, the risk was 5.1% and 5.65%, respectively [27].

Any case of unexpected vaginal bleeding in a woman using combined MHT, cyclical as well as continuous, ought to be meticulously studied. Most frequent causes of unexpected bleeding in MHT users are non-compliance, liver diseases, drug-to-drug interference, benign neoplasms such as endometrial or cervical polyps, cervical inflammation, or extragenital (urinary or gastrointestinal) pathology [25].

Incidence data on vaginal bleeding in women using combined MHT, oral as well as transdermal, vary significantly between 0 and 77% [28].

As we have demonstrated above, incidence of bleeding in continuous combined oral MHT users decreases considerably after the first six to 12 months of use, with just 3-9% expected to present with unscheduled bleedings after nine months of MHT. In transdermal estrogen users, the incidence of bleeding after 12 months of therapy is 10-20% [29].

Thus, clinicians need to address two key issues as an MHT user presents with an unscheduled vaginal bleeding episode:

- Exclude endometrial cancer;

- Confirm the etiology of the acyclical bleeding for subsequent choice of pathogenetic and/or symptomatic treatment.

Diagnosis and treatment strategy

1. Collect a detailed patient history.

- When does the bleeding occur?

- Which medicines does the patient take?

- Has the patient been non-compliant with her MHT regimen?

- Is the bleeding post-coital?

- When did the patient last undergo cervical examination?

2. Examine the pudendum, vagina, and cervix, targeting:

- Visual signs of hemorrhage or lesions, including any signs of atrophy;

- Exact localization of the bleeding (possibilities include vagina, urethra, or rectum).

3. Refer the patient for ultrasonography (subsequent strategy will largely depend on the US findings, which places an extra emphasis on the ultrasonographist’s expertise).

See Table 2 for method to use the findings for step-by-step exclusion of possible PMB causes [28–30].

|

Table 2. Possible causes of bleeding in MHT users |

||

|

Cause |

Detailed |

Strategy |

|

Uterine conditions |

Adenomyosis Submucous myoma Polyps, endometritis Endometritis with atrophy Endometrial hyperplasia / cancer |

Diagnosing and excluding the listed conditions |

|

Cervical conditions |

Cervical cancer Cervicitis |

Diagnosing and excluding the listed conditions |

|

Compliance issues |

Missing pills Taking the wrong pill from the blister, etc. |

Educating the patient on the importance of compliance, long-term effects, causal relationship between MHT non-compliance and PMB |

|

Drug-to-drug interference |

Medicines affecting estrogen and gestagen metabolism:

|

Confirming ongoing therapy with an interfering drug, educating the patient on the possible cause of PMB, continuing MHT after the discontinuation of the interfering therapy |

|

Gastrointestinal conditions, chronic and acute |

Gastrointestinal diseases affecting drug absorption, such as:

|

Detecting, diagnosing, and treating the listed conditions |

|

Obesity |

Elevated production of endogenous estrogens by adipose tissue, possibly affecting the endometrium |

Educating the patient on the need for lifestyle correction (eating habits, physical exercise), tailoring therapy to the patient’s history (possibly lower estrogen dosage) |

|

Estrogen / gestagen ratio |

|

Correcting the Estrogen / gestagen ratio |

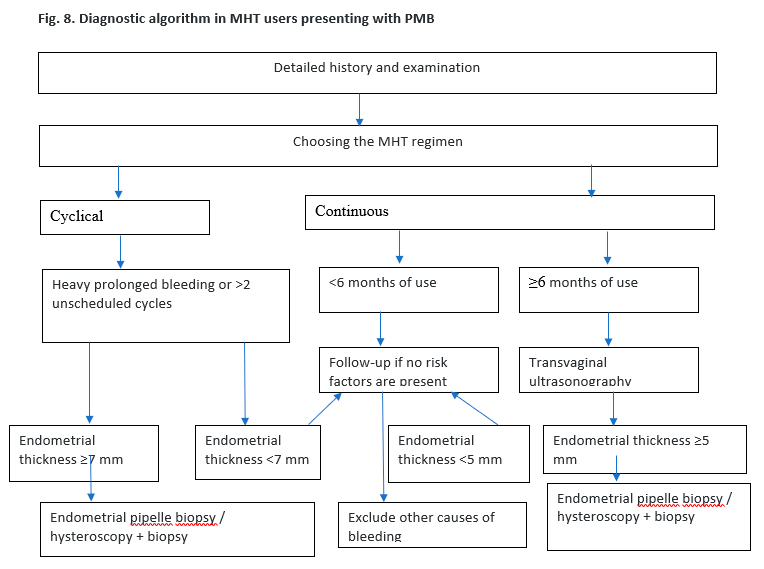

4. Upon performing the steps in Table 2, see Figure 8 for the choice of subsequent tactics.

5. Consider the following possibilities, as endometrial pathology and other causes are excluded, depending on the type of MHT used:

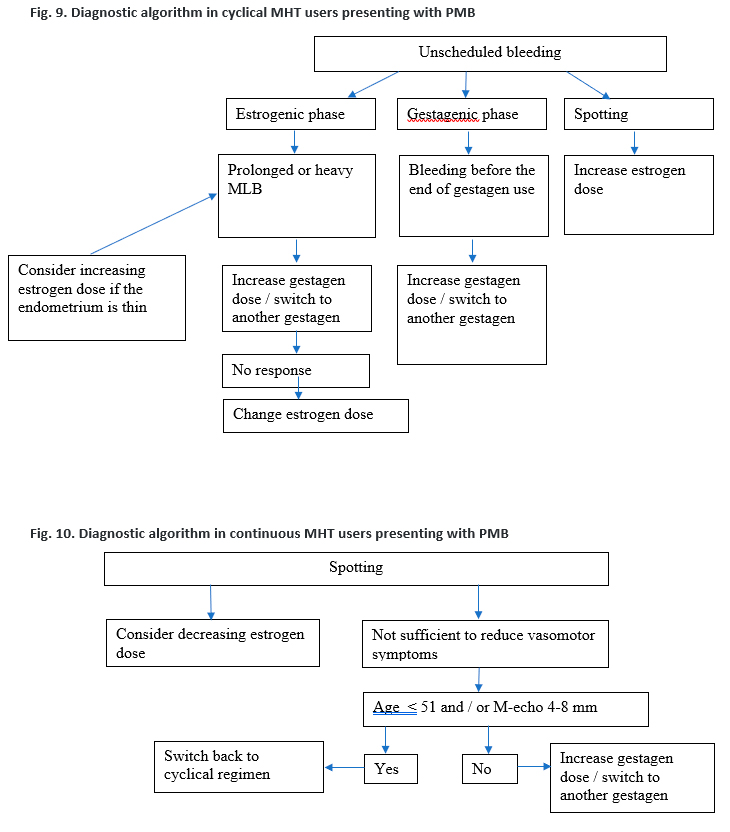

А. Unscheduled bleeding in a cyclical regimen user [28, 30] (Figure 9).

Б. Unscheduled bleeding in a continuous regimen user [28, 30] (Figure 10).

Switching patients from combined oral contraceptives to MHT

As of this writing, there is no universal guidance on indications for, and the pathway of, switching patients from the use of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) to MHT.

According to the findings of the All-Russian MHT Survey, about 90% of doctors reported having switched their patients from COC to MHT [31]. Most widely used strategies were “stop COC – start MHT” (61%) and “stop COC – wait (no therapy) – start MHT” (28%). 11% of respondents included additional considerations, such as apparent age of menopause, or limiting the no-therapy period after COC to six to eight weeks, or looking at the FSH level before starting MHT after COC.

Only 25% of Russian COC users take COCs for the primary purpose of contraception. In 75% of cases, COCs are prescribed for therapeutic purposes, which may be suboptimal [32].

Age could be used as a marker for the need for switching. After the age of 40, women should undergo annual hormonal contraception risks vs. benefits assessment [33, 51]. In such an assessment, the presence of more than one of the following factors [34] should also lead to a deeper analysis:

- age (< / ≥35 years), smoking (< / ≥ 15 cigarettes per day), obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²), high blood pressure;

- venous thromboembolism, surface vein thrombosis, dyslipidemia, aggravated cardiovascular history (ischemic heart disease, stroke or other thromboembolic conditions), migraines etc.

The following factors could lead to termination or discontinuation of COC use:

- risks vs. benefits assessment;

- absence of a sexual partner;

- temporary discontinuation of COC for other reasons (planned surgery, immobilization etc.).

If vasomotor symptoms emerge after COC discontinuation, MHT should be considered.

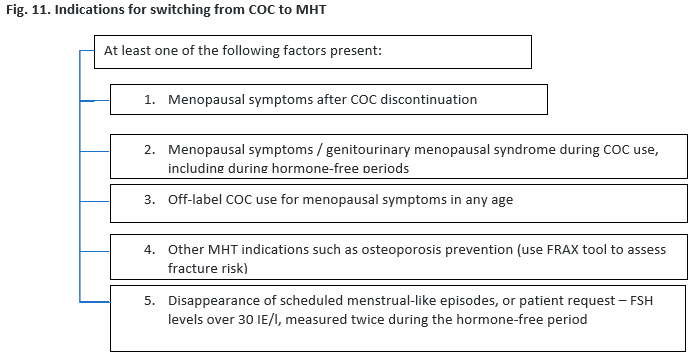

See Figure 11 for the possible indications for switching from COC to MHT.

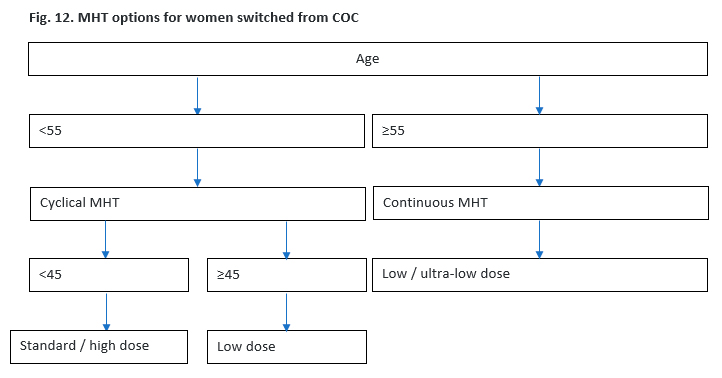

See Figure 12 for the MHT options for switchers.

In two to three months after switching to MHT, the patient should undergo a switching assessment for efficacy, possible side effects, discharge (if any); pelvic ultrasonography should be considered if needed. The patient needs to be educated that MHT medicines do not provide contraception and therefore other methods of contraception (such as barrier) are to be used if the need arises.

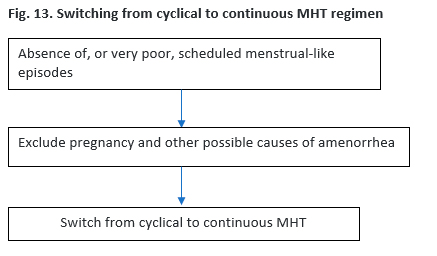

If the user of a cyclical MHT regimen expects menstrual-like episodes but remains totally or nearly amenorrheic, and pregnancy or other causes of amenorrhea can be excluded, switching to continuous MHT regimen may be considered (see Figure 13).

Conclusion

Medical intervention is undoubtedly key in improving the general health and quality of life in women presenting with menopausal symptoms. We hope that the algorithms presented above will become instrumental in improving the clinical management of menopause and personalizing menopausal therapy. This paper aims to become an everyday practical guide for all healthcare professionals concerned, making healthy and active longevity a real possibility for many women and thus contributing to the prevention of medical, demographic, social, and economic losses across the nation.

The algorithms presented above will remain subject to additions and revisions as new guidelines and evidence become available internationally.

References

- https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/world-demographics/ Accessed 20 Jan 2021.

- Ulumbekova G.E., Khudova I.Yu. Assessing the demographic, social, and economic effects of menopausal hormonal therapy. ORGZDRAV: news, opinions, training. Healthcare Organizers Higher School Bulletin. 2020; 6(4): 23-53. (in Russian only)

- Turner R.J., Kerber I.J. Eu-estrogenemia, WHI, timing and the "Geripause". Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008; 19(11): 1461-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0708-6.

- Turner R.J., Kerber I.J. A theory of eu-estrogenemia: a unifying concept. Menopause. 2017; 24(9): 1086-97. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000895.

- Yureneva S.V., Dubrovina A.V. Benefits of a timely/early start of menopausal hormonal therapy in the context of euestrogenemia theory. Russian Obstetrician and Gynecologist’s Bulletin. 2018; 18(5): 49-55. (in Russian only)

- Miller V.M., Kling J.M., Files J.A., Joyner M.J., Kapoor E., Moyer A.M. et al. What’s in a name: are menopausal ‘‘hot flashes’’ a symptom of menopause or a manifestation of neurovascular dysregulation? Menopause. 2018; 25(6):700-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001065.

- Tepper P.G., Brooks M.M., Randolph J.F. Jr., Crawford S.L., El Khoudary S.R., Gold E.B. et al. Characterizing the trajectories of vasomotor symptoms across the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2016; 23(10): 1067-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000676.

- Baber R.J., Panay N., Fenton A.; the IMS Writing Group. 2016 IMS Recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric. 2016; 19(2): 109-50. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2015.1129166.

- Clarkson T.B. Estrogen effects on arteries vary with stage of reproductive life and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis progression. Menopause. 2018; 25(11): 1262-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001228.

- Hodis H.N., Mack W.J., Shoupe D., Azen S.P., Stanczyk F.Z., Hwang-Levine J. et al. Methods and baseline cardiovascular data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol testing the menopausal hormone timing hypothesis. Menopause. 2015; 22 (4): 391-401. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000343.

- Bild D.E., Bluemke D.A., Burke G.L., Detrano R., Diez Roux A.V., Folsom A.R. et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002; 156 (9): 871-81. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf113.

- Manson J.E., Chlebowski R.T., Stefanick M.L., Aragaki A.K., Rossouw J.E., Prentice R.L. et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013; 310(13): 1353-68. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278040.

- Roehm E. A reappraisal of Women’s Health Initiative Estrogen-Alone Trial: long-term outcomes in women 50–59 years of age. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2015; 2015: 713295.

- Panay N., Anderson R.A., Nappi R.E.., Vincent AJ., Vujovic S., Webber L., Wolfman W. Premature ovarian insufficiency: an International Menopause Society White Paper. Climacteric. 2020; 23(5): 426-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2020.1804547.

- Radzinsky V.E. Essays on Endocrine Gynecology. Moscow, Status Praesens Media Bureau; 2020. 576p. (in Russian only)

- Patient Information Leaflet, Femoston® 1, 08.10.2019.

- Patient Information Leaflet, Femoston ® 2, 14.10.2019.

- Patient Information Leaflet, Femoston ® mini, 28.05.2019.

- Patient Information Leaflet, Femoston ® conti, 10.10.2019.

- Australian Menopause Society. Available at: https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/management/early-menopause. Accessed 20 Jan 2021.

- Appendix 6B – Guidance on management of the menopause in primary care. Available at: https://www.fifeadtc.scot.nhs.uk/formulary/6-endocrine/appendix-6b-management-of-menopause-in-primary-care.aspx.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017; 24(7): 728-53. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000921.

- Tsiligiannis S., Wick-Urban B.C., van der Stam J., Stevenson J.C. Efficacy and safety of a low-dose continuous combined hormone replacement therapy with 0.5 mg 17β-estradiol and 2.5 mg dydrogesterone in subgroups of postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms. Maturitas. 2020; 139: 20-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.002.

- Munro M.G.; Southern California Permanente Medical Group’s Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Working Group. Investigation of women with postmenopausal uterine bleeding: clinical practice recommendations. Perm. J. 2014; 18(1): 55-70. https://dx.doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-072.

- Carugno J. Clinical management of vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women, Climacteric. 2020; 23(4): 343-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2020.1739642.

- Clarke M.A., Long B.J., Del Mar Morillo A., Arbyn M., Bakkum-Gamez J.N., Wentzensen N. Association of endometrial cancer risk with postmenopausal bleeding in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018; 178(9): 1210-22. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2820.

- Bengtsen M.B., Veres K., Nørgaard M. First-time postmenopausal bleeding as a clinical marker of long-term cancer risk: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Br. J. Cancer. 2020; 122(3): 445-51. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0668-2.

- Dave F.G. Laiyemo R., Adedipe T. Unscheduled bleeding with hormone replacement therapy. Obstetrician Gynaecologist. 2019; 21(2): 95-101. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/tog.12553.

- Sathiyathasan S., Kannappar J., Lou Y.Y. Unscheduled bleeding on HRT – do we always need to investigate for endometrial pathology? Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017; 6(10): 4174-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20174391.

- de Medeiros S.F., Yamamoto M.M., Barbosa J.S. Abnormal bleeding during menopause hormone therapy: insights for clinical management. Clin. Med. Insights Womens Health. 2013; 6: 13-24. https://dx.doi.org/10.4137/CMWH.S10483.

- https://www.menopause-russia.org/news/primite-uchastie-vo-vserossiyskom-anketirovanii-po-naznacheniyu-i-primeneniyu-mgt/ Accessed 24.02.2021.

- Authors’ clinical experience.

- FSRH Clinical Guideline Combined Hormonal Contraception (January 2019, Amended November 2020). Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/combined-hormonal-contraception/ Accessed 20 Jan 2021.

- WHO. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Fruzzetti F., Paoletti A.M., Fidecicchi T., Posar G., Giannini R., Gambacciani M. Contraception with estradiol valerate and dienogest: adherence to the method. Open Access J. Contracept. 2019; 10: 1-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/OAJC.S204655.

- Australian Menopause Society https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/management/treatment-options (Access date 20 Jan 2021).

- NICE guideline Menopause: diagnosis and management (NG23, published Nov 2015). Available at: nice.org.uk/guidance/NG23. Accessed 20 Jan 2021.

- Anagnostis P., Bitzer J., Cano A., Ceausu I., Chedraui P., Durmusoglu F. et al. Menopause symptom management in women with dyslipidemias: an EMAS clinical guide. Maturitas. 2020; 135: 82-88. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.03.007.

- Slopien R., Wender-Ozegowska E., Rogowicz-Frontczak A., Meczekalski B., Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz D., Jaremek J.D. et al. Menopause and diabetes: EMAS clinical guide. Maturitas. 2018; 117: 6-10. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.08.009.

- Kuh D., Cooper R., Moore A., Richards M., Hardy R. Age at menopause and lifetime cognition: Findings from a British birth cohort study. Neurology. 2018; 90(19): e1673-e1681. https://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005486.

- de Villiers T.J., Gass M.L., Haines C.J., Hall J.E., Lobo R.A., Pierroz D.D., Rees M. Global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric. 2013; 16(2): 203-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2013.771520.

- Ettinger B. Effect of the Womenʼs Health Initiative on womenʼs decisions to discontinue postmenopausal hormone therapy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003; 102(6): 1225-32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.08.007.

- Crawford S.L., Crandall C.J., Derby C.A., El Khoudary S.R., Waetjen L.E., Fischer M., Joffe H. Menopausal hormone therapy trends before versus after 2002: impact of the Women's Health Initiative Study Results. Menopause. 2018; 26(6): 588-97. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001282.

- Chlebowski R.R., Anderson G.G. Changing concepts: menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012; 104: 517-27. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djs014.

- Fournier A., Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008; 107(1): 103-11. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10549-007-9523-x.

- Vinogradova Y., Coupland C., Hippisley-Cox Ju. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2020; 371: m3873. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3873.

- Telli M.L., Gradishar W.J., Ward J.H. NCCN Guidelines updates: breast cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2019; 17(5.5): 552-5. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.6004/jnccn.2019.5006.

- Torrens J.I., Sutton-Tyrrell K., Zhao X., Matthews K., Brockwell S., Sowers M., Santoro N. Relative androgen excess during the menopausal transition predicts incident metabolic syndrome in mid-life women. Menopause. 2009; 16(2): 257-64. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318185e249.

- Markopoulos M.C., Kassi E., Alexandraki K.I., Mastorakos G., Kaltsas G. Hyperandrogenism after menopause. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015; 172(2): R79-91. https://dx.doi.org/10.1530/EJE-14-0468.

- Wierman M.E., Arlt W., Basson R., Davis S.R., Miller K.K., Murad M.H. et al. Androgen therapy in women: A reappraisal: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014; 99(10): 3489-510. https://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-2260.

- Dubrovina S.O. Rational approach to hormonal therapy in women aged over 40. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; 7:112-16. https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.7.112-116 (in Russian only)