Algorithms for the management of patients with endometriosis: an agreed position of experts from the Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

For citation: Sukhikh G.T., Serov V.N., Adamyan L.V., Baranov I.I., Bezhenar V.F., Gabidullina R.I., Dubrovina S.O., Kozachenko A.V., Podzolkova N.M., Smetnik A.A., Tapilskaya N.I., Uvarova E.V., Shikh E.V., Yarmolinskaya M.I. Algorithms for the management of patients with endometriosis: an agreed position of experts from the Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.Sukhikh G.T., Serov V.N., Adamyan L.V., Baranov I.I., Bezhenar V.F., Gabidullina R.I., Dubrovina S.O., Kozachenko A.V., Podzolkova N.M., Smetnik A.A., Tapilskaya N.I., Uvarova E.V., Shikh E.V., Yarmolinskaya M.I.

Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya/Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (5):159-176 (in Russian)

https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.132

Endometriosis is a chronic pathological process. It is characterized by the presence of tissue, which is similar to endometrium in terms of its morphological and functional properties, outside the uterine cavity [1–9]. The etiology and pathogenesis of the disease have not been fully identified yet [4].

Endometriosis has serious adverse consequences on women's health and quality of life [1–10]. The most significant clinical manifestations of the disease are pelvic pain (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia and chronic pelvic pain), infertility, menstrual disorders, abnormal uterine bleeding [1–10].

With the development of medicine, it became clear that a personalized approach to the management of patients with endometriosis was necessary. The management strategy for women patients should be aimed at improving their quality of life by reducing pain, treating infertility, reducing the frequency of relapses of the disease and repeated surgical interventions [1–9].

Surgical methods and medical therapy are used for endometriosis treatment. According to international and Russian clinical recommendations, the main type of medical treatment in the absence of contraindications is hormone therapy [1–4]. Due to the chronic nature of the disease, hormone therapy is prescribed for a long period of time and can be extended to menopause, and in some cases, it can be used after the menopause if it is feasible from the clinical point of view [11–14]. The choice of a specific treatment regimen depends on the needs of a specific patient, the severity of symptoms and the response to treatment [1–9, 12–14].

Timely appointment of rationally selected therapy leads to a decrease in the unfavorable manifestations of endometriosis, which has a beneficial effect on the quality of women's life, while reducing the negative social, demographic and economic consequences of the disease (disability, decline of women fertility, additional treatment costs) [10, 11].

Endometriosis affects approximately 190 million women worldwide (10%) [10]. Despite the presence of international and Russian clinical recommendations, the problem and the need for improved treatment still remain. According to the UBP-WRS study, 67% of women with endometriosis have impaired quality of life, i.e. they need relevant treatment [10]. There are about 2 million women suffering from endometriosis in Russia, about 1.1 million of whom need hormone therapy, and only 24% of them actually get it. The reasons are different: low awareness of patients about the disease, fear of doctors and the lack of clear algorithms for prescribing therapy, continuity between the inpatient and outpatient stages, undesirable effects of medicines, self-cancellation of prescribed treatment by women.

The developed algorithms are an efficient tool for the daily clinical practice. They will personalize the endometriosis therapy, which will contribute to the successful management of patients with symptoms and provide an opportunity to make a personal contribution to the overall goal of national well-being and prosperity. A doctor being aware of a process to personalize endometriosis therapy can significantly improve a woman's quality of life and help her realize life plans. The presented step-by-step algorithms reflect the coordinated position of experts of the Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ROAG), with due consideration of the current clinical recommendations [1–9, 15–17], advanced scientific data and actual Russian clinical experience [12, 18–23].

Providing medical care for patients with endometriosis at outpatient and inpatient stages

A patient with complaints related to endometriosis most often comes to an outpatient clinic, where the initial diagnosis and selection of treatment occur. Endometriosis hormone therapy is offered as an independent treatment or as a second stage after surgery [1–11].

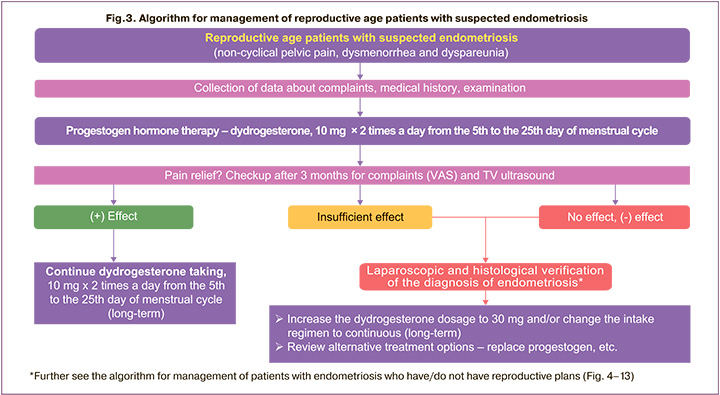

In the healthcare system of the Russian Federation, organizational measures are taken to increase the frequency of hormone therapy application among those women to whom it is indicated: informing women, training doctors, actively identifying patients, timely diagnosis and choice of treatment method, monitoring the course of treatment, compiling registers of women in need of the therapy [10]. If there are indications for endometriosis surgical treatment, the organization of medical care for patients consists of several stages (Fig. 1). After an examination at an outpatient clinic, the patient is sent to a hospital for endometriosis surgical treatment. Further, outpatient follow-up and hormone therapy are recommended (Fig. 1). Increasing women's adherence to prescribed treatment requires a continuous approach between outpatient and inpatient care stages due to high risk of the disease recurrence.

There are four approaches for determining the recurrence of endometriosis [5]: 1) based on anamnesis data; 2) based on imaging data (ultrasound, MRI); 3) based on laparoscopic imaging data without histological confirmation; 4) based on histological examination of surgical material.

Treatment of endometriosis is complex and includes medical and surgical methods [1–4]. Surgical treatment is recommended mainly using laparoscopic access in patients with genital endometriosis (in the presence of conditions and the absence of contraindications) in order to determine the extent of the disease spread and to remove foci [24–26]. Surgical and medical methods of treatment should not be contrasted. Advantages and disadvantages of each method should be carefully analyzed before starting treatment, taking into account the individual properties of the case. This will minimize negative results and, on the contrary, maximize positive ones [27].

The problem of endometriosis recurrence is considered as one of the most complex in the world [1–10, 28]. The ESHRE Guideline on Endometriosis (2022) dedicates a separate chapter to recurrence, which emphasizes the particular importance of this problem [1–3]. The endometriosis recurrence rate after surgical treatment is 15–21% after 1–2 years, 36-47% after 5 years and 50–55% after 5–7 years [11]. Endometriosis recurrence can be caused by a patient's refusal from hormone therapy due to undesirable effects and/or lack of understanding of the importance of the stage of medical treatment after surgery. According to a Swiss study, 39.3% of women with endometriosis independently discontinued dienogest therapy due to undesirable effects or the lack of its efficiency [29].

Informing women before treatment about the disease, the need for long-term therapy, possible adverse events caused by medicines and ways to solve these problems will reduce the risk of refusal to take medicines and subsequent recurrence of endometriosis [13, 28].

For this purpose, at the stage of inpatient and outpatient care, the following measures are advisable in order to minimize the risk of endometriosis recurrence:

1. to inform the patient that endometriosis is a chronic disease that usually requires long-term treatment before menopause with interruptions for implementation of reproductive function and lactation, follow-up;

2. to explain the risks of surgical treatment, complications in the absence of treatment or refusal to take the prescribed medicines to the patient;

3. to talk to the patient about the importance of the postoperative outpatient stage of observation and treatment using hormone therapy as indicated;

4. to take into account the needs and wishes of the patient when choosing hormone therapy for endometriosis;

5. to inform the patient about possible side effects during hormone therapy and ways to solve the problem.

Endometriosis medical therapy

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used for pain syndrome relief for a short period of time, both in the form of monotherapy and in combination with progestogens. In the presence of central sensitization (neuropathic pain), the use of neuromodulators as empirical medical therapy (without surgical verification of diagnosis) is recommended in the absence of cystic forms of endometriosis and other tumors and tumor-like formations of the genital organs [4, 17, 30].

Progestogens, hormonal contraceptives, agonists or antagonists of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) are currently used to reduce endometriosis- associated pain (antagonists are not registered in Russia) [1–4]. The use of danazol in patients with endometriosis is limited due to high incidence of adverse events [4]. If the hormone therapy is not efficient, aromatase inhibitors may be prescribed, including in combination with oral contraceptives, progestogens, Gn-RH agonists or antagonists [1–3].

It should be emphasized that the ESHRE guideline on endometriosis (2022) notes the proven benefits of all the above hormone medications [1–3].

In accordance with the position of RSOG (2020), combined oral contraceptives (COCs) are intended primarily for contraception [4, 31] in the absence of contraindications. It is known that the risk of developing deep infiltrative endometriosis in women who have previously taken COCs for primary dysmenorrhea increases [32], and large doses of estrogens in COCs can contribute to the progression of the disease [33].

According to modern approaches, when choosing a hormone therapy, it is recommended to use a joint approach to decision-making, consider personal features and preferences of women, undesirable effects, individual effectiveness, cost and availability of medicines [1–3].

Progestogens are used most often in medical practice in the territory of the Russian Federation. According to the clinical recommendations of RSOG (2020) progestogens are considered the first line treatment for endometriosis and are used as hormone therapy after surgery to prevent the disease recurrence [4, 10]. Progestogens can be taken in continuous and prolonged cyclical regimen to ensure glandular epithelium atrophy, decidualization of the stromal component as well as in the cyclical regimen in the second phase of the menstrual cycle in patients with endometriosis planning pregnancy [4]. Progestogens are recommended by ESHRE (2022) experts for treatment of endometriosis-associated pain and for the prevention of recurrences after surgical treatment [1–3].

Dydrogesterone, dienogest, norethisterone are the most well studied progestogens registered in Russia for the endometriosis treatment. In the absence of significant differences in efficiency, progestogens have a different safety profiles and possibility of treatment personalizing [1–9, 14, 18, 34–36]. Given the duration of therapy, it is important to take into account their safety profile in order to adapt treatment to reduce symptoms and improve the quality of life of women when prescribing progestogens [1–3]

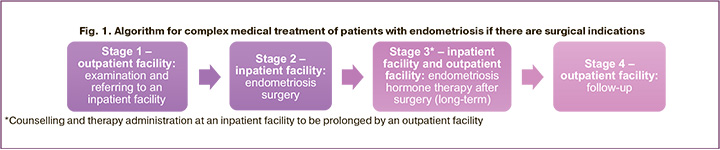

High affinity for progesterone receptors will provide the main pharmacological effect of the medicine, and in the presence of a link with other steroid receptors, there is a high risk of adverse events. According to published data, the affinity of dydrogesterone for progesterone receptors is 75%, dienogest – 5% (Fig. 2) [37]. Given the possible presence of progesterone resistance, it is important that the association of progestogen with progesterone receptors is higher than that of progesterone itself. The main differentiating feature and advantage of dydrogesterone in comparison with other progestogens is its high selectivity for progesterone receptors, which reduces the likelihood of adverse events due to interaction with other receptors (Fig. 2) [37, 38]. The lack of a connection between dydrogesterone and androgenic, glucocorticoid, mineral-corticoid receptors causes the absence of a number of undesirable reactions in case this medicine is used [37, 38].

Taking of progestogens having affinity for other receptors, in addition to progesterone, can lead to the development of adverse events [29]. Therefore, patients independently refuse to take the prescribed treatment, which contributes to recurrences of the disease [26, 39]. A number of researchers note a minimal risk of recurrence of pain with prolonged endometriosis therapy with progestogens [12, 18, 21, 22, 25].

Personalization of therapy for women with endometriosis will be presented on the example of dydrogesterone, which allows demonstrating algorithms for managing patients in various clinical situations. Dydrogesterone offers several regimens of use, which makes it possible to manage therapy, select the necessary dosages (10–30 mg), regimens (cyclical, prolonged cyclical, continuous) and increase patient compliance. At the same time, it is important to note that these algorithms are applicable to any progestogens for which the corresponding application regimens are registered.

Management of reproductive age patients with complaints of pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia

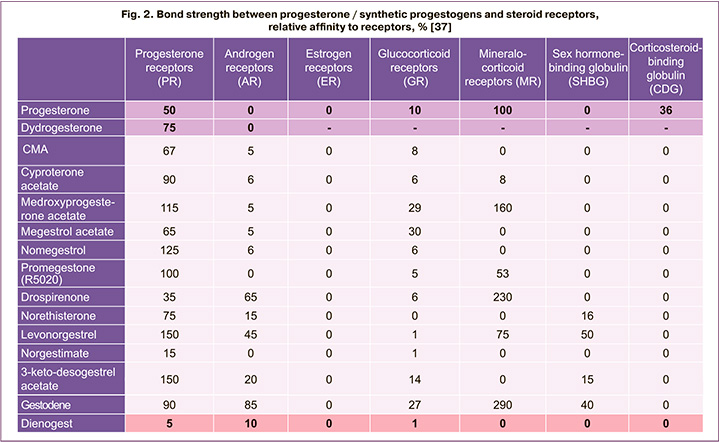

The management of patients of reproductive age with complaints of pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia is determined by the position of Russian and international experts in accordance with algorithms presented in Figure 3.

The diagnosis of endometriosis is established on the basis of complaints and anamnesis of patients, physical examination, as well as instrumental methods of examination (ultrasound examination of lesser pelvis organs, MRI of lesser pelvis organs, diagnostic laparoscopy) [4].

According to the ESHRE Guidelines for Endometriosis (2022), laparoscopy is recommended for patients with the mentioned complaints in the absence of ultrasound or MR signs of endometriosis, as well as in case of empirical treatment inefficiency [1–3]. Laparoscopy in case of suspected endometriosis is indicated in the following cases: in the presence of pain syndrome, in the absence of the effect of conservative treatment, at the stage of pregnancy planning.

In the presence of ultrasound or MR signs of endometriosis in women of reproductive age who are not currently planning pregnancy, and in the absence of indications for surgical treatment, long-term progestogen therapy is possible [40].

In a patient with suspected endometriosis with chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia (possibly with bleeding and infertility) after a thorough assessment of complaints, physical examination and transvaginal ultrasound (TV ultrasound), including for the presence of ovarian space-occupying lesions and their size, further methodology is determined. If there is a unilateral or bilateral lesion of ≥30 mm (O-RADS 2), it is recommended to assess ovarian reserve and enucleate the wall of the endometrial cyst after its emptying and washing the cavity to completely remove the lesion in order to morphologically verify the diagnosis and reduce the frequency of recurrence [4], after which hormone therapy should be prescribed with assessment of its efficiency after 3 months (follow-up) by symptoms (visual analog scale (VAS)) and according to TV ultrasound.

To a patient of reproductive age with suspected endometriosis in accordance with the current instructions for medical use can be prescribed dydrogesterone (of progestogen group) for the indication "dysmenorrhea" (2 times x 10 mg per day from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle). If contraception is a priority for the patient, then the use of COCs is possible [4]. The treatment efficiency should be assessed after 3 months. If the effect of dydrogesterone is positive, it is recommended to take it 10 mg twice a day on days 5 to 25 of the menstrual cycle for a long period of time with interruptions for implementation of reproductive plans and lactation if necessary. In case of insufficient effect or aggravation of symptoms, laparoscopic and histological verification of the diagnosis of endometriosis with further increase in the dosage of dydrogesterone to 30 mg/day is recommended, or a change in the regimen of dydrogesterone to a continuous one and an increase in the dosage to 30 mg/day, or a replacement of progestogen (Fig. 3).

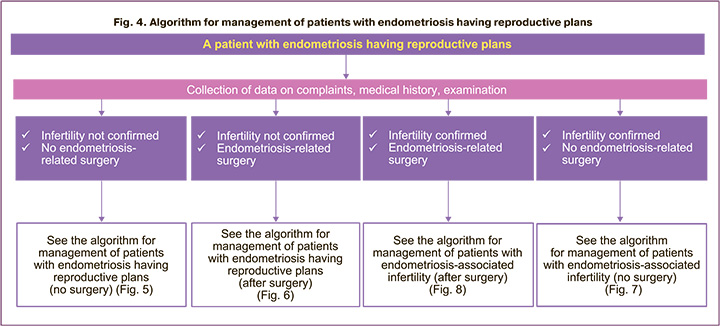

Management of patients with endometriosis having reproductive plans

The main issues that will determine the choice of methods for the management of patients with endometriosis having reproductive plans (Fig. 4) are as follows:

1. whether infertility is diagnosed;

2. whether there is a need for surgery for endometriosis.

Endometriosis affects 25–50% of fertile women, and 30–50% of women with endometriosis have infertility [4, 41]. Endometriosis is detected in 58% of women undergoing laparoscopy as the final stage of examination for infertility [4, 42, 43]. The issue of the reproductive function's implementation due to age, concomitant diseases, ovarian reserve and other circumstances may require a quick and most effective solution in a short time.

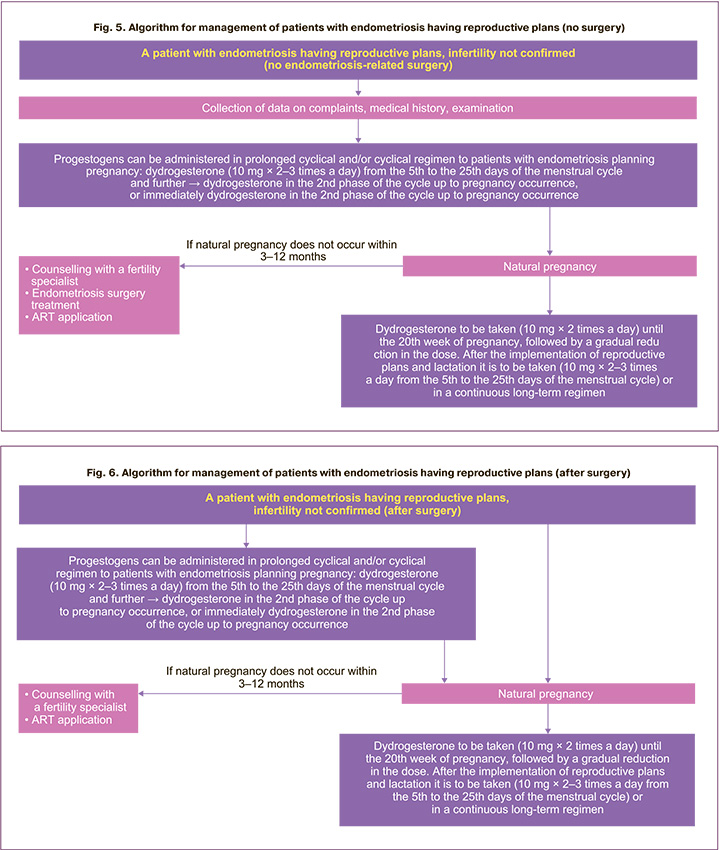

The algorithm for management of a patient with endometriosis having reproductive plans without an established diagnosis of infertility is given in Figures 5 and 6. Indications for surgical treatment in women with endometriosis having reproductive plans are discussed with the patient. Then the doctor and the patient jointly determine further treatment scheme (Fig. 5, 6).

In some cases, with contraindications, a refusal of surgery, or if a woman has previously undergone surgical treatment, the patient is prepared for a possible natural pregnancy using, for example, dydrogesterone. Currently there is no convincing data for suppressive therapy of endometriosis to increase the chances of pregnancy [1–3], therefore, an option can be considered of managing a woman, for example, using dydrogesterone in a cyclical regimen to correct the menstrual cycle's luteal phase insufficiency, pre-implantation preparation of the endometrium (Fig. 5–8). In accordance with the clinical recommendations of the RSOG on endometriosis, it is possible to use progestogens in a cyclical regimen in the second phase of the menstrual cycle in patients with endometriosis planning for pregnancy [4]. At the same time, in individual cases (for example, in the presence of severe pain syndrome, the need to postpone the implementation of reproductive function, for additional examination of a woman or partner, etc.), it is possible to use dydrogesterone in a prolonged cyclical regimen from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle 10 mg 2–3 times a day for the relief of symptoms, regression of endometrioid foci (Fig. 5–8), and then, if the patient is ready for pregnancy, transfer to a cyclical regimen to correct the insufficiency of the menstrual cycle's luteal phase. If it is impossible to achieve natural pregnancy within 3–12 months (depending on the clinical situation and age of the patient), it is recommended to refer the patient to a reproductive specialist, to decide on the surgical treatment of endometriosis and/or the use of ART (Fig. 5). Dydrogesterone also has another advantage. It can be taken during pregnancy at 20 mg per day until the 20th week of pregnancy, followed by a gradual reduction in the dose, and after the implementation of reproductive plans and lactation for the treatment of endometriosis – 10 mg 2–3 times a day in a prolonged cyclical regimen (from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle) or in a continuous regimen (daily). In addition, long-term cycle is advisable (until menopause or further planning of pregnancy).

The algorithm for management of a patient with endometriosis having reproductive plans without an established diagnosis of infertility after surgery is shown in Figure 6. Post-surgery hormone suppression should not be prescribed for women seeking to become pregnant for the sole purpose of increasing the frequency of future pregnancies [1–4]. Hormone therapy can be offered immediately after surgery to those women who delayed the implementation of reproductive plans since it does not have a negative effect on fertility and improves the result of surgical intervention [1–3]. However, in a number of specific cases it is possible to offer the patient, for example, dydrogesterone in a prolonged cyclical regimen and then in a cyclical regimen or immediately in a cyclical regimen for pregravid preparation. If a patient is unable to achieve natural pregnancy within 3–12 months (depending on the clinical situation), it is recommended to refer the patient to a reproductive specialist, to decide on the use of ART (Fig. 5, 6). Given the high risk of miscarriage in patients with endometriosis [42], the advantage of dydrogesterone is also that a pregnant patient can continue taking it at 20 mg daily until the 20th week of pregnancy, followed by a gradual dose reduction, and after implementation of reproductive plans and lactation for the treatment of endometriosis – 10 mg 2–3 times a day in a prolonged cyclical (days 5 to 25 of the menstrual cycle) or in continuous regimen (daily), long-term treatment is appropriate until menopause or further pregnancy planning.

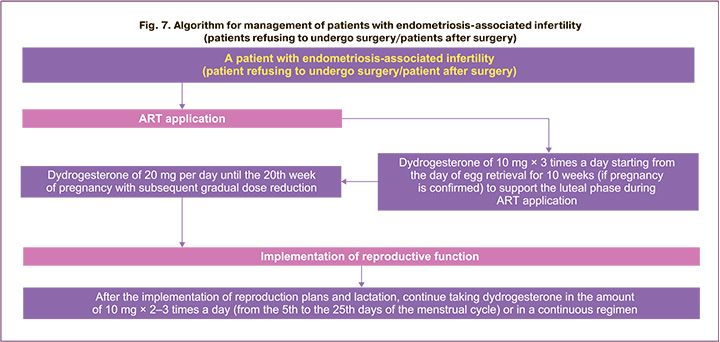

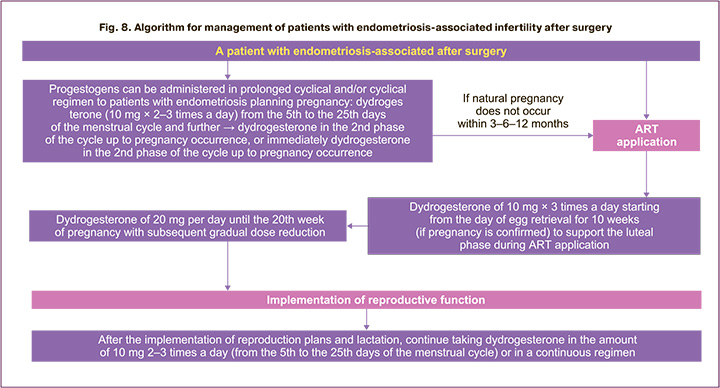

Infertility is one of the most significant complaints in endometriosis [1–4] and requires special methods of patient management. The algorithm for the management of patients with endometriosis-associated infertility is shown in Figures 7 and 8. Indications for surgical treatment of women with endometriosis- associated infertility are to be discussed with the patient and further treatment method is jointly determined (Fig. 7, 8).

It is recommended to make a decision on surgery taking into account the presence or absence of pain symptoms, the age and preferences of the patient, the history of previous surgeries, the presence of other factors of infertility, ovarian reserve and the calculated fertility index for endometriosis [1–3].

In accordance with the recommendations of the RSOG (2020), surgical treatment of patients with infertility and endometriosis with any degree of spread of the process is recommended, as this improves the reproductive prognosis [4, 16]. Surgical treatment by laparoscopic access is recommended in small or moderate forms of endometriosis, which improves the rates of pregnancy onset [4]. Doctors may consider laparoscopy for the treatment of infertility associated with endometrioma, since this method can increase the chances of patients for natural pregnancy, although there is no data from comparative studies [1–3]. In patients with infertility in stage I/II endometriosis (AFS/ASRM), it is recommended to surgically remove the foci of endometriosis in full to increase the frequency of live birth [4]. Also, laparoscopy in patients with endometriosis suffering from infertility allows to expand the search for the causes of infertility, identify concomitant disorders or diseases (inflammation, adhesion, impaired patency of the fallopian tubes) and correct them [4]. At the same time, the removal of small endometriomas before in vitro fertilization (IVF) is not recommended, especially in case of repeated surgeries with a confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis [1–3]. Nevertheless, the surgical treatment remains mandatory in the presence of suspicious results of ultrasound and in women with pelvic pain syndrome. Both expectant and surgical management of ovarian endometrioma in women planning ART have potential benefits and risks that should be carefully evaluated before making a decision. An assessment of the ovarian reserve (monitoring of the level of anti-Müllerian hormone and antral follicles counting) is required before planning surgical treatment in patients with ovarian endometriomas [4, 17].

In some cases (with contraindications, refusal of surgery, or if the woman has previously undergone surgical treatment), the patient is to be prepared for ART and then managed in accordance with the algorithm shown in Figure 7. There is data that before preparing a patient with endometriosis for IVF Gn-RH agonists with add-back replacement therapy can be prescribed from 3 to 6 months before ART procedure, however, there is no evidence of an increased likelihood of pregnancy in this case [1–4]. In the process of ART application, it is possible to prescribe dydrogesterone to support the luteal phase of the cycle of 10 mg 3 times a day starting from the day of egg retrieval for 10 weeks (if pregnancy is confirmed) with further prolongation of dydrogesterone administration of 20 mg per day until the 20th week of pregnancy with subsequent gradual dose reduction. After the implementation of reproduction plans and lactation, it is possible to continue taking, for example, dydrogesterone in the amount of 10 mg 2–3 times a day in a prolonged cyclical regimen (from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle) or in a continuous regimen (daily), while a long course is advisable – until menopause or further planning of pregnancy (Fig. 7). If it is impossible to achieve pregnancy within 3 to 12 months (depending on the clinical situation) using ART or in case of miscarriage, a decision shall be taken on surgical treatment of endometriosis and further actions are to be determined.

The algorithm for the management of patients with endometriosis-associated infertility after surgical treatment of endometriosis is presented in Figure 8. It is recommended to use ART methods to achieve pregnancy after surgical treatment in women with endometriosis of the 3-4th stage and impaired patency of the fallopian tubes regardless of the patient's age and fertility of the husband, in case surgical treatment and conservative treatment for 3–12 months prove to be ineffective [4].

After the surgical treatment of endometriosis, it is necessary to determine whether hormone therapy is required. According to RSOG (2020) and ESHRE (2022) recommendations, it is not recommended to prescribe hormone treatment after surgery in case of radical removal of foci to improve spontaneous pregnancy rates to patients with endometriosis-associated infertility [1–4]. In individual cases, when a woman needs to postpone the implementation of reproductive plans for some reason, there is a successful practice of prescribing hormone therapy immediately after surgery, since it does not adversely affect fertility and improves the results of surgery [1–3].

The high efficiency of combined treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility (surgery + dydrogesterone) makes it possible to obtain a long- awaited pregnancy in more than 80% of patients [12]. Methods that can effectively treat the disease or control it without inhibiting ovulation are advisable for the treatment of endometriosis, as they allow women get pregnant during the therapy [1–3, 44].

The dydrogesterone's mechanism of action differs from that of other progestogens as in therapeutic doses the medicine does not suppress ovulation and therefore it is the only progestogen that is suitable for patients with endometriosis planning pregnancy [37, 38, 42, 45, 46]. Previously, it was believed that the suppression of ovulation, which is provided by COCs, is necessary in the treatment of endometriosis. A study conducted by Santulli R. et al., showed that oligo- anovulation occurred in patients with and without endometriosis with equal frequency [47]. Consequently, these results reject the intuitive belief that oligo- anovulation may provide some protection against endometriosis [47].

As endometriosis is one of the common causes of infertility and miscarriages, it is advisable to take progestogens during pregnancy [12–14, 45, 46]. After the reproductive function implementation, endometriosis therapy with dydrogesterone can be continued.

Assumptions about the benefits of prescribing dydrogesterone in the luteal phase in case of endometriosis-associated infertility have been made [48] with an increased likelihood of pregnancy [12, 49, 50]. It is a proven fact that dydrogesterone reduces the risk of sporadic and spontaneous pathological termination of pregnancy with luteal phase insufficiency. Its reception is expedient during pregnancy, since the risk of spontaneous pathological termination of pregnancy is increased by 1.7–3.0 times in case of endometriosis [45, 46, 50].

For patients planning pregnancy with infertility and endometriosis a cyclical regimen of dydrogesterone after surgery in the second phase of the menstrual cycle can help to get the long-awaited opportunity to implement reproductive plans independently or using ART [12].

Management of patients with endometriosis having no reproductive plans

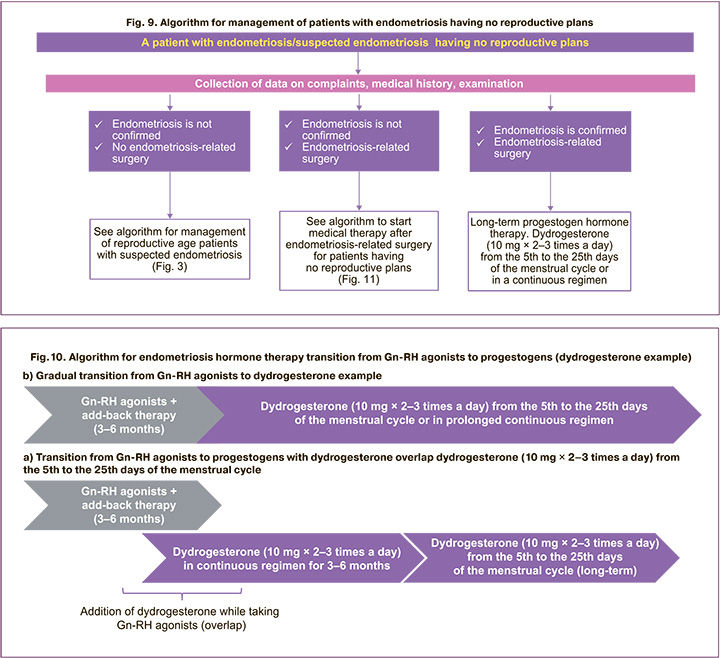

The algorithm of patient management in the absence of reproductive plans with endometriosis/suspected endometriosis is shown in Figure 9.

The main issues determining the methods for management of patients with endometriosis having no reproductive plans after the surgical stage are the following:

1. the need for prescription of Gn-RH agonists;

2. choice of progestogen.

In some cases, a question arises of the need to prescribe Gn-RH agonists after the surgical treatment of endometriosis. Gn-RH agonists can be used for several months prior to progestogens [14, 51, 52] or alternate with progestogens in case of insufficient relief of pain or in case of intractable bleedings in combination with "add-back" therapy to prevent adverse events in patients who do not respond to progestogens or other hormone therapy and avoid surgery due to high surgical risk [1–4, 14] ESHRE and RSOG experts recommend considering add-back therapy along with Gn-RH agonist therapy to prevent adverse events such as bone loss and hypoestrogenic symptoms [1–4].

After withdrawal of GnRH agonists, a doctor faces a question of choosing a medicine for further treatment, usually progestogen. Most often this happens after 3–6 months. The algorithm for transition of endometriosis hormone therapy from Gn-RH agonists to progestogens (Fig. 10) will maximize the outcome of the treatment. Currently, the sequential transition from Gn-RH agonists to progestogens is the most commonly used practice (Fig. 10a). At the same time, a number of risks must be taken into account. There is a high risk of a break in treatment and, as a result, a recurrence of pain, a decrease in the effectiveness of the treatment at the time of transition from Gn-RH agonists to progestogens. Dydrogesterone and Gn-RH agonist “overlap” is possible (Fig. 10b). In such a case, the therapy is not interrupted, the risk of treatment interruption at the time of transition from Gn-RH agonists to progestogens is eliminated, and, as a result, the risk of pain recurrence is absent/minimized, the efficiency of the treatment is increased.

Due to the fact that the Gn-RH agonist therapy is limited in time, and endometriosis has a chronic course, it is important to initially focus on the first line of therapy of the disease, progestogens. If Gn-RH agonists should be prescribed, the doctor should select the optimal progestogen for the patient for a long- term treatment with the possibility of successfully implementing reproductive plans, if any.

The selection of progestogen (dydrogesterone, dienoest, norethisterone) for endometriosis treatment is determined taking into account the following factors: high efficacy, reliable safety profile with prolonged use, a possibility of therapy personalization. Dydrogesterone is reliably effective and safe in two regimens (prolonged cyclical and continuous) in terms of reducing chronic pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea, which in ORCHID study led to noticeable improvements in all studied parameters related to quality of life and sexual well- being [18]. In patients who received dydrogesterone for 6 months, the number of days during which analgesics were required was significantly reduced [18]. Nowadays, most patients want to keep menstruation for the entire endometriosis treatment period [13]. The ORCHID study demonstrates that the duration of the menstrual cycle did not significantly change from the statistical point of view during the therapy with dydrogesterone both in a continuous and prolonged cyclical regimen [18]. Thus, dydrogesterone meets the current requirements of endometriosis therapy and meets the wishes of most women.

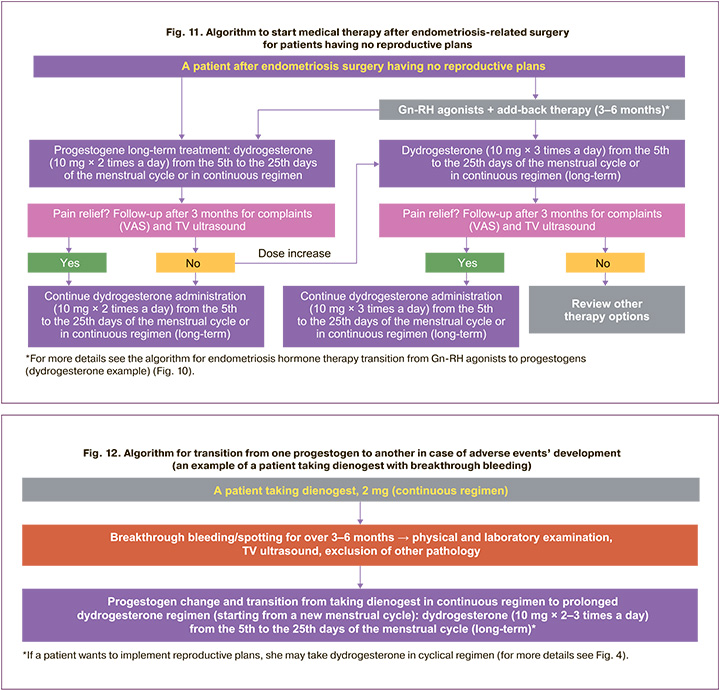

The starting dosage of dydrogesterone can be minimal – 20 mg per day, the regimen of the medicine depending on the patient's need can be continuous or prolonged cyclical. When assessing the pain syndrome in dynamics after 3 months (according to VAS scale), as well as following ultrasound results, the dosage of dydrogesterone can be increased to 30 mg/day at any time, apart from that, the regimen can be changed. If the pain is relieved, it is recommended to continue taking dydrogesterone according to the selected scheme and dosage for a long period of time (Fig. 11). If necessary, changes in dosage and regimen can be implemented without additional examinations. In the absence of positive changes, it is necessary to continue the search for optimal therapy (Fig. 11).

High efficiency, reliable safety profile of dydrogesterone in endometriosis and the presence of different regimens of its use make it possible to vary the registered dosages (10–30 mg), regimens (continuous, prolonged cyclical, cyclical) depending on the needs of the doctor and patient [12, 18]. All this allows you to choose an adequate dose and regimen for the relief of endometriosis-associated pain, and reduce the risk of adverse events, including avoiding breakthrough bleeding [13].

Management of patients with endometriosis if a change of therapy is needed

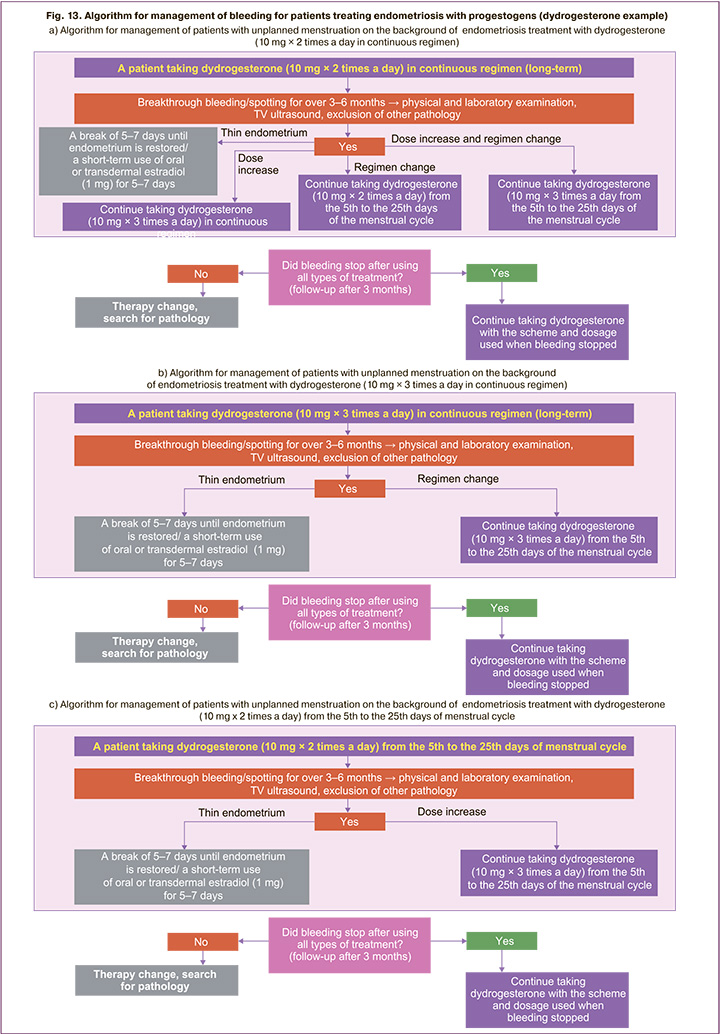

The incidence of an adverse medicine reaction, such as uterine bleeding, in patients will depend on the progestogen therapy regimen [19, 53]. Dydrogesterone provides doctors and patients with an opportunity to minimize the risk of breakthrough bleeding if registered prolonged cyclical regimen from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle and different dosages are used [18]. In ORCHID large-scale multicenter study on the use of dydrogesterone in patients with endometriosis (2018–2020), there were no cases of uterine bleeding in the prolonged cyclical regimen group 0/273 (0.0%) [18]. With continuous administration of progestogens, irregular bleeding is possible in the first 3 months of treatment in about 20% of patients [54]. Abnormal uterine bleeding may require further examination using TV ultrasound, physical and laboratory examination, including screening for sexually transmitted diseases such as Chlamydia trachomatis [15, 55].

When managing a patient with endometriosis, it is important to inform her about possible bleeding against the background of taking progestogens, and a change in the nature of bleeding. In this case, it is advisable for a woman to consult a doctor. It is important to explain to the patient that bleeding occurring when taking progestogens is not a sign of inadequate therapy or a recurrence of the disease. Low sonographic thickness of endometrium will indicate possible atrophy. In this case, a break of 5–7 days is required to restore the endometrium, a short-term use of oral or transdermal estradiol (1 mg) for 5–7 days is also possible [56]. The preservation of abnormal uterine bleeding should encourage further studies to exclude other pathologies of the uterus, in addition to endometriosis [56].

With the development of bleeding in patients using dienogest within 3–6 months after the examination (physical and laboratory, TV ultrasound) and if no other pathology is identified, the patient can be transferred to dydrogesterone, as dienogest having one continuous regimen only offers only limited capabilities in terms of overcoming a number of side effects. The transition from a continuous progestogen treatment regimen to a prolonged cyclical regimen is carried out with the beginning of a new menstrual cycle: dydrogesterone 10 mg 2–3 times a day from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle (long-term). If a patient wishes to implement reproductive plans, it is possible to transfer her to the dydrogesterone cyclical regimen in the second phase (for more details, see Fig. 4).

Figure 13 shows the algorithm for the management of women with bleeding while taking progestogen for endometriosis treatment. Dydroesterone is used as an example. If a patient with endometriosis bleeds while taking dydrogesterone in a continuous regimen at 20 mg/day, she may continue taking the medicine after examinations (physical and laboratory, TV ultrasound) and if no other pathology is identified. Other treatment options may be considered (Fig. 13a):

1. keep the current dydrogesterone continuous regimen, increase the dosage to 30 mg/day;

2. change the dydrogesterone regimen to prolonged cyclical from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle, the dosage is the same, 20 mg/ day;

3. change the dydrogesterone regimen to prolonged cyclical from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle, increase the dosage to 30 mg/ day;

If bleeding is observed in the presence of dydrogesterone continuous regimen at a dosage of 30 mg/day, then the regimen can be changed to a prolonged cyclical one from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle while maintaining the daily dosage (30 mg/day) (Fig. 13b).

If bleeding is observed while taking dydrogesterone from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle at a dosage of 20 mg/day, then the dosage can be increased to 30 mg/day (Fig. 13c).

It is necessary to assess the clinical situation and condition of the patient within 3–6 months of treatment. If the bleeding stopped, then it is necessary to continue taking dydrogesterone using the selected scheme. With ongoing bleeding, it is necessary to search for endometrial pathology, in the absence of such it is required to change therapy (Fig. 13).

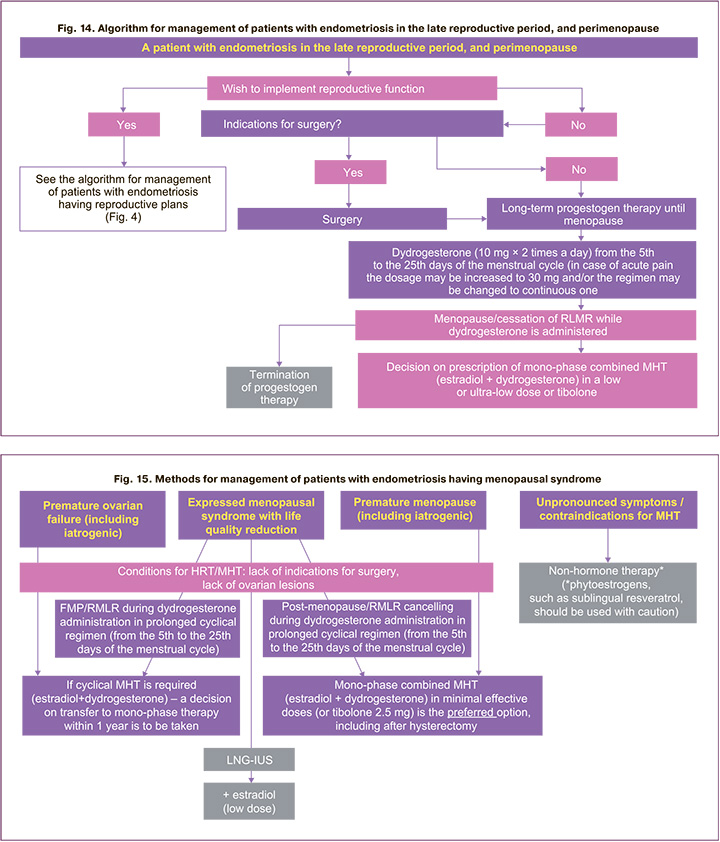

Management of patients with endometriosis in the late reproductive period, peri- and postmenopause

The incidence of endometriosis in postmenopausal women is 2-5% [57, 58]. Patient management algorithm for endometriosis in the late reproductive period and perimenopause (Fig. 14) provides a doctor with a plan of action in the relevant clinical situation. When managing postmenopausal patients a doctor should take into account the risk of malignancy, as well as the possibility of prescribing menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) if indicated [4]. In the presence of infertility in women in the late reproductive period or perimenopause, it is advisable to apply treatment methods in accordance with the algorithms for managing patients with endometriosis-associated infertility (Fig. 4). It is also necessary to determine whether the patient has indications for surgical treatment of endometriosis. After the surgery or in the absence of indications for surgical treatment, hormone therapy with progestogens is prescribed for a long time – until the onset of menopause/cessation of a regular menstruation-like reaction (RMLR) in case of cyclic administration of progestogens. In this case, dydrogesterone 10 mg 2 times a day from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle is preferred, in case of acute pain, the dosage may be increased to 30 mg per day.

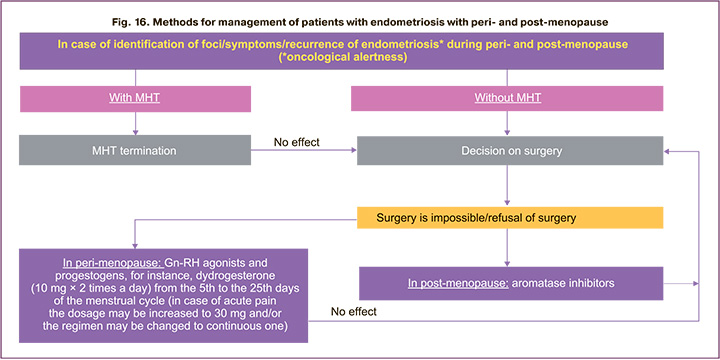

In post-menopause, it is possible to take a decision on prescription of mono-phase combined MHT (for example, estradiol + dydrogesterone) in a low or ultra- low dose or tibolone (Fig. 14–16) in the presence of indications and the absence of contraindications to MHT. Cases of foci/symptoms/recurrences of endometriosis in the peri- and post-menopause both in case of using MHT and without it are described, as well as examples of newly diagnosed endometriosis. When detecting endometrioid cysts of the ovary and extragenital forms of the disease, oncological alertness should be manifested [4, 59].

According to RSOG (2020) clinical recommendations on endometriosis, surgical treatment of women with endometriosis of any location is recommended, especially in the presence of voluminous genital formations, if possible, by laparoscopic access, in postmenopausal patients both in order to eliminate mass lesion and to exclude oncological diseases [4].

Treatment of patients in case of foci/ symptoms/ recurrences of endometriosis in peri- or post- menopause and the algorithm of medical methods are presented in Figure 16. It should be remembered that with persistence of endometriosis in post-menopause, the risk of malignancy increases, which requires immediate surgical treatment [4]. If the recurrence occurs during MHT, then therapy should be canceled and, in the absence of necessary effect, the question of endometriosis surgical treatment should be resolved. If it is impossible to perform surgery in perimenopause, it is possible to prescribe Gn-RH agonists or progestogens (dydrogesterone 10 mg 2 times a day from the 5th to the 25th days of the menstrual cycle, in case of acute pain, the dosage can be increased to 30 mg), in post- menopause – aromatase inhibitors with the obligatory patient follow-up (Fig. 14–16).

The algorithm of the doctor's actions in the development of menopausal syndrome in patients with endometriosis is shown in Figure 15. Depending on the clinical situation, history, severity of manifestations of menopause, further methods and possibilities of using hormone therapy are determined. Doctors should avoid prescribing estrogen-only regimens to treat vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a history of endometriosis, as these regimens may be associated with a higher risk of malignant transformation [1–4].

According to ESHRE (2022), tibolone has no advantages over mono-phase combined MHT [1–3]. Ultrasound monitoring of the lower pelvis organs during the entire period of treatment is performed after 3, 6, 12 months.

Conclusions

Endometriosis is a chronic disease, the purpose of its treatment is to achieve relief of pain syndrome, improve the reproductive health and quality of patients' life. Patients require long-term personalized medical therapy depending on their age, reproductive motivations and clinical manifestations. Currently, the best available means for endometriosis treatment are hormone medications. Therapy of choice for endometriosis in foreign and Russian recommendations are progestogens. Algorithms are one of the key and convenient formats for presenting medical information, since a clear understanding of the doctor's scheme of action in a particular clinical situation helps to make the choice of treatment for the most effective result.

The presented algorithms for the management of patients with endometriosis are a joint position of the leading Russian experts in the field of gynecology. They are developed on the basis of modern domestic and foreign data and current clinical recommendations.

These algorithms will help improve clinical approaches to the management of patients with endometriosis in the daily practice of each doctor. This will contribute to maintaining the quality of life and reproductive health of women, having a significant impact on the prevention of medical, demographic, social and economic losses in Russia. As new international recommendations and scientific research become available, the presented algorithms will be supplemented and updated. Algorithm developers are always happy to receive proposals for further improvement of the document.

References

1. ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Development Group. Endometriosis. Guideline of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. 2022. 192p. Available at: https://www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/ Endometriosis-guideline

2. Becker C.M., Bokor A., Heikinheimo O., Horne A., Jansen F., Kiesel L. et al.; ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2022; 2022(2): hoac009. https://dx/doi.org/10.1093/hropen/ hoac009.

3. Becker C.M., Bokor A., Heikinheimo O., Horne A., Jansen F., Kiesel L. et al. Guideline of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE): endometriosis (translation into Russian, edited by V.N. Serov, A.A. Smetnik, S.O. Dubrovina). Obstetrics and gynecology: news, opinions, training. 2023; 11(1): 67-93. https://dx.doi.org/10.33029/ 2303-9698- 2023-11-1-67-93.

4. Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Endometriosis. Clinical guidelines. Moscow; 2020. (in Russian).

5. International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C., Johnson N.P., Petrozza J., Abrao M.S., Einarsson J.I., Horne A.W. et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2021; 2021(4): hoab029. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoab029.

6. Practice bulletin no. 114: management of endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010; 116(1): 223-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b073.

7. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2014; 101(4): 927-35. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.fertnstert.2014.02.012.

8. Chinese Obstetricians and Gynecologists Association; Cooperative Group of Endometriosis, Chinese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chinese Medical Association. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis (Third edition). Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2021; 56(12): 812-24. (in Chinese). https://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112141-20211018-00603.

9. Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain Training Center of Shandong Medical Doctor Association WANG Guoyun, WANG Kai, YUAN Ming, CHEN Zijiang. Multidimensional management system for endometriosis (The Program for Shandong Province). Journal of Shandong University (Health Sciences). 2021; 59(10): 1-17.

10. Ulumbekova G.E., Khudova I.Yu. Demographic, social and economic effects of hormonal therapy in endometriosis and abnormal uterine bleeding. HEALTHCARE MANAGEMENT: News, Views, Education. Bulletin of VSHOUZ. 2022; 8(1): 82-113. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.33029/2411- 8621-2022-8-1-82-113.

11. Adamyan L.V., Andreeva E.N. Endometriosis and its global impact on a woman’s body. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2022; 28(1): 54-64. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro20222801154.

12. Bezhenar V.F., Kruglov S.Yu., Kuzmina N.S., Krylova Yu.S., Sergienko A.S., Abilbekova A.K., Zhemchuzhina T.Yu. Effectiveness of long-term hormone therapy for endometriosis after surgical treatment. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; (4): 134-42. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2021.4.134-142.

13. Dubrovina S.O., Berlim Yu.D., Aleksandrina A.D., Vovkochina M.A., Bogunova D.Yu., Gimbut V.S., Bozhinskaya D.M. Modern ideas about the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023; (2): 146-53. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2023.43.

14. Dubrovina S.O., Berlim Yu.D. Drug treatment for endometriosis- related pain. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; (2): 34-40. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.18565/aig.2019.2.34-40.

15. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin N 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012; 120(1): 197-206. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ AOG.0b013e318262e320.

16. Leyland N., Casper R., Laberge P., Singh S.S.; SOGC. Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2010; 32(7, Suppl. 2): S1-32.

17. National Guideline Alliance (UK). Endometriosis: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); Sep. 2017.

18. Sukhikh G.T., Adamyan L.V., Dubrovina S.O., Baranov I.I., Bezhenar V.F., Kozachenko A.V. et al. Prolonged cyclical and continuous regimens of dydrogesterone are effective for reducing chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis: results of the ORCHIDEA study. Fertil. Steril. 2021; 116(6): 1568-77. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.07.1194.

19. Adamyan L.V., Sonova M.M., Loginova O.N., Tikhonova E.S., Iarotskaia E.L., Zimina É.V., Murdalova Z.Kh., Shamugia N.M., Laskevich A.V. The comparative analysis of effectiveness of dienogest and leuprorelin in the complex treatment of genital endometriosis. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2013; (4): 33-8. (in Russian).

20. Popov A.A., Fedorov A.A., Manannikova T.N., Abramian K.N., Orlova S.A., Zingan Sh. The combined approach (laparoscopy + dienogest) for endometrios- associated infertility treatment. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2016; 22(4): 76-80. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro201622476-80.

21. Iarmolinskaia M.I., Florova M.S. The possibility of treatment with dienogest 2 mg in patients with genital endometriosis. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2017; 23(1): 70-9. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/repro201723170-79.

22. Yarmolinskaya M.I., Florova M.S., Andreeva N.Y. Experience of long-term use of dienogest in patients with external genital endometriosis. Journal of Obstetrics and Women's Diseases. 2016; 65(Suppl.): 78-9. (in Russian).

23. Podzolkova N.M., Fadeev I.E., Glazkova O.L., Gorozhanina A.A., Kuznetsov R.E. Efficacy of combination therapy in patients with deep infiltrating endome- triosis. Issues of Gynecology, Obstetrics and Perinatology. 2022; 21(5): 105-12. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.20953/1726-1678-2022-5-105-112.

24. Dunselman G.A.J., Vermeulen N., Becker C., Calhaz-Jorge C., D'Hooghe T., De Bie B. et al.; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014; 29(3): 400-12. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det457.

25. Bedaiwy M.A., Allaire C., Alfaraj S. Long-term medical management of endometriosis with dienogest and with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and add-back hormone therapy. Fertil. Steril. 2017; 107(3): 537-48. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.12.024.

26. Dubrovina S.O., Bezhenar V.F., ed. Endometriosis. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment. Moscow.: GEOTAR-Media; 2020. 352 p. (in Russian).

27. Pantou A., Simopoulou M., Sfakianoudis K., Giannelou P., Rapani A., Maziotis E. et al. The role of laparoscopic investigation in enabling natural conception and avoiding in vitro fertilization overuse for infertile patients of unidentified aetiology and recurrent implantation failure following in vitro fertilization. J. Clin. Med. 2019; 8(4): 548. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jcm8040548.28.

28. Busacca M., Candiani M., Chiàntera V., Coccia M.E., De Stefano C. et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Ital. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018; 30(2): 7-21. https://dx.doi.org/10.14660/2385-0868-85.

29. Nirgianakis K., Vaineau C., Agliati L., McKinnon B., Gasparri M.L., Mueller M.D. Risk factors for non-response and discontinuation of Dienogest in endometriosis patients: A cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021; 100(1): 30-40. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13969.

30. Leonardi M., Gibbons T., Armour M., Wang R., Glanville E., Hodgson R. et al. When to do surgery and when not to do surgery for endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020; 27(2): 390-407.e3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.10.014.

31. Yarmolinskaya M.I., Adamyan L.V. Hormonal contraceptives and endometriosis: modern view on the problem. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2020; 26(3): 39 45. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.17116/ repro20202603139.

32. Chapron C., Souza C., Borghese B., Lafay-Pillet M.-C., Santulli P., Bijaoui G. et al. Oral contraceptives and endometriosis: the past use of oral contracep- tives for treating severe primary dysmenorrhea is associated with endometriosis, especially deep infiltrating endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2011; 26(8): 2028-35. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ humrep/der156.

33. Casper R.F. Progestin-only pills may be a better first-line treatment for endome- triosis than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptive pills. Fertil. Steril. 2017; 107(3): 533-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.01.003.

34. Trivedi P., Selvaraj K., Mahapatra P.D., Srivastava S., Malik S. Effective post-laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis with dydrogesterone. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2007; 23(Suppl. 1): 73-6. https://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/09513590701669583.

35. Kitawaki J., Koga K., Kanzo T., Momoeda M. An assessment of the efficacy and safety of dydrogesterone in women with ovarian endometrioma: An open-label multicenter clinical study. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2021; 20(3): 345-51. https://dx.doi. org/10.1002/rmb2.12391.

36. Liang B., Wu L., Xu H., Cheung C.W., Fung W.Y., Wong S.W., Wang C.C. Efficacy, safety and recurrence of new progestins and selective progesterone receptor modulator for the treatment of endometriosis: a comparison study in mice. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018; 16(1): 32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/ s12958-018-0347-9.

37. Schindler A.E., Campagnoli C., Druckmann R., Huber J., Pasqualini J.R., Schweppe K.W., Thijssen J.H. Classification and pharmacology of pro- gestins. Maturitas. 2008; 61(1-2): 171-80. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.maturitas.2008.11.013.

38. Rižner T.L., Brožič P., Doucette C., Turek-Etienne T., Müller-Vieira U., Sonneveld E. et al. Selectivity and potency of the retroprogesterone dydro- gesterone in vitro. Steroids. 2011; 76(6): 607-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.steroids.2011.02.043.

39. Dubrovina S.O., Berlim Yu.D., Aleksandrina A.D., Vovkochina M.A., Tsirkunova N.S., Bogunova D.Yu. Endometriosis in routine practice: analysis of clinical cases. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2022; (6): 152-61. (in Russian). https://dx.doi. org/10.18565/aig.2022.6.152-161.

40. Podzolkova N.M., Fadeev I.E., Mass E.E., Poletova T.N., Sumyatina L.V., Denisova T.V. Noninvasive diagnosis and conservative therapy of endometriosis. Gynecology. 2022; 24(3): 167-73. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.26442/20 795696.2022.3.201508.

41. Somigliana E., Vercellini P., Vigano P., Benaglia L., Busnelli A., Fedele L. Postoperative medical therapy after surgical treatment of endometriosis: from adjuvant therapy to tertiary prevention. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014; 21(3): 328-34. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2013.10.007.

42. Lee S.Y., Kim M.L., Seong S.J., Bae J.W., Cho Y.J. Recurrence of ovarian endometrioma in adolescents after conservative, laparoscopic cyst enucleation. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017; 30(2): 228-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.jpag.2015.11.001.

43. Tomassetti C., Bafort C., Meuleman C., Welkenhuysen M., Fieuws S., D'Hooghe T. Reproducibility of the endometriosis fertility index: a prospective inter-/ intra-rater agreement study. BJOG. 2020; 127(1): 107-14. https://dx.doi. org/10.1111/1471-0528.15880.

44. Vercellini P., Buggio L., Berlanda N., Barbara G., Somigliana E., Bosari S. Estrogen-progestins and progestins for the management of endome- triosis. Fertil. Steril. 2016; 106(7): 1552-71.e2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.fertnstert.2016.10.022.

45. Gabidullina R.I., Koshelnikova E.A., Shigabutdinova T.N., Melnikov E.A., Kalimullina G.N., Kuptsova A.I. Endometriosis: impact on fertility and preg- nancy outcomes. Gynecology. 2021; 23(1): 12-7. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.26442/20795696.2021.1.200477.

46. Shikh E.V., ed. Pharmacotherapy during pregnancy. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2020. 208 p. (in Russian).

47. Santulli P., Tran C., Gayet V., Bourdon M., Maignien C. Marcellin L. et al. Oligo-anovulation is not a rarer feature in women with documented endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2018; 110(5): 941-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.fertnstert.2018.06.012.

48. Hodgson R.M., Lee H.L., Wang R., Mol B.W., Johnson N. Interventions for endometriosis-related infertility: a systematic review and network meta- analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2020; 113(2): 374-82.e2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.fertnstert.2019.09.031.

49. Orazov M.R., Radzinsky V.E., Khamoshina M.B., Kavteladze E.V., Shustova V.B., Tsoraeva Yu.R., Novginov D.S. Endometriosis-associated infertility: from myths to harsh reality. Difficult Patient. 2019; 17(1-2): 16-22. (in Russian). https:// dx.doi.org/10.24411/2074-1995-2019-10001.

50. Orazov M.R., Khamoshina M.B., Mikhaleva L.M., Volkova S.V., Abitova M.Z., Shustova V.B., Khovanskaya T.N. Molecular genetic features of the state of endometry in endometriosis-associated infertility. Difficult Patient. 2020; 18(1): 6-15. (in Russian). https://dx.doi.org/10.24411/2074-1995-2020- 10005.

51. Kitawaki J., Ishihara H., Kiyomizu M., Honjo H. Maintenance therapy involv- ing a tapering dose of danazol or mid/low doses of oral contraceptive after gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment for endometriosis-associ- ated pelvic pain. Fertil. Steril. 2008; 89(6): 1831-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.fertnstert.2007.05.052.

52. Kitawaki J., Kusuki I., Yamanaka K., Suganuma I. Maintenance therapy with dienogest following gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment for endometriosis-associ https://dx.doi.org/ated pelvic pain. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011; 157(2): 212-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.ejogrb.2011.03.012.

53. Kim S.E., Lim H.H., Lee D.Y., Choi D. The long-term effect of dienogest on bone mineral density after surgical treatment of endometrioma. Reprod. Sci. 2021; 28(5): 1556-62. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s43032-020-00453-7.

54. Kim S.A., Um M.J., Kim H.K., Kim S.J., Moon S.J., Jung H. Study of dienogest for dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2016; 59(6): 506-11. https://dx.doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2016.59.6.506.

55. Singh S., Best C., Dunn S., Leyland N., Wolfman W.L.; CLINICAL PRACTICE – GYNAECOLOGY COMMITTEE. Abnormal uterine bleeding in pre- menopausal women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2013; 35(5): 473-5. https:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30939-7.

56. Murji A., Biberoğlu K., Leng J., Mueller M.D., Römer T., Vignali M., Yarmolinskaya M. Use of dienogest in endometriosis: a narrative literature review and expert commentary. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2020; 36(5): 895-907. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2020.1744120.

57. Вadescu A., Roman H., Aziz M., Puscasiu L., Molnar C., Huet E. et al. Mapping of bowel occult microscopic endometriosis implants surrounding deep endo- metriosis nodules infiltrating the bowel. Fertil. Steril. 2016; 105(2): 430-4.e26. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.006.

58. Gubbels A.L., Li R., Kreher D., Mehandru N., Castellanos M., Desai N.A., Hibner M. Prevalence of occult microscopic endometriosis in clinically negative peritoneum during laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020; 151(2): 260-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13303.

59. De Almeida Asencio F., Ribeiro H.A., Ribeiro P.A., Malzoni M., Adamyan L., Ussia A. et al. Symptomatic endometriosis developing several years after menopause in the absence of increased circulating estrogen concentrations: a systematic review and seven case reports. Gynecol. Surg. 2019; 16(1). https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s10397-019-1056-x.

About the Authors

Expert Work Group for the Algorithms' Development:Gennady T. Sukhikh, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Director of the Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Moscow).

Vladimir N. Serov, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Chief Researcher, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of Russia, President of the Russian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Moscow).

Leila V. Adamyan, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Deputy Director for Research, Head of the Gynecological Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Moscow).

Igor I. Baranov, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Scientific and Educational Programs, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Moscow).

Vitaliy F. Bezhenar, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Departments of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Neonatology/Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductology,

First St. Petersburg State Medical University named after Academician I.P. Pavlov of the Ministry of Health of Russia; Chief External Expert for Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Health Committee of the Government of St. Petersburg (St. Petersburg).

Rushanya I. Gabidullina, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology named after Professor V.S. Gruzdev, Kazan State Medical University

of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Kazan).

Svetlana O. Dubrovina, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Chief Researcher of the Research Institute of Obstetrics and Pediatrics, Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 1, Rostov State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Rostov-on-the-Don).

Andrey V. Kozachenko, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Chief Researcher of Gynecology Department, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Moscow).

Natalia M. Podzolkova, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Russian Medical Academy of Continuing Professional Education of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Moscow).

Antonina A. Smetnik, PhD, Head of the Department of Gynecological Endocrinology, Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Moscow).

Natalia I. Tapilskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Leading Researcher of the Reproduction Department, Research Institute of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction named after D.O. Ott; Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, St. Petersburg State Pediatric Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia

(St. Petersburg).

Elena V. Uvarova, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Associate Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of the 2nd Gynecological Department (Children and Youth Gynecology), Academician V.I. Kulakov National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology of the Ministry of Health of Russia; Professor of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatology and Reproduction of IPO, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University) (Moscow).

Evgenia V. Shikh, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor, Head of the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases of the Institute of Clinical Medicine named after N.V. Sklifosovsky, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia (Sechenov University) (Moscow).

Maria I. Yarmolinskaya, Dr. Med. Sci., Professor of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of the Department of Gynecology and Endocrinology, Head of the Center for Diagnostics and Treatment of Endometriosis, Research Institute of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction named after D.O. Ott; Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, I.I. Mechnikov North-Western State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia (St. Petersburg).